Cultural differences in politeness as a function of status relations: Comparing South Korean and British communicators

Abstract

Although politeness is an important concern in communications across cultures, a prevalent assumption in psychology is that East Asians are more inclined to be polite than members of other cultural groups due to prevalent cultural norms. Yet, evidence for this assumption is mixed. The present research examined this issue by considering the role of social hierarchy in interpersonal communications of Korean and British participants (N = 220) using an experimental task that involved writing an email to decline a request made by a junior or a senior person. The results showed that Korean participants’ emails were more polite when addressing a senior colleague compared with a junior colleague in work contexts. In contrast, recipient status did not impact British participants’ politeness. Crucially, cultural differences in politeness only emerged when participants addressed a senior colleague, but not when participants addressed a junior colleague. We discuss the implications of these findings and directions for future research.

Confucianism has shaped social and political value systems in many East Asian countries, including China and Japan. South Korea is a point in case, where Confucian values and heritage remain an important aspect of modern life in spite of the clear influence of globalization (see Bae & Rowley, 2001; Horak & Yang, 2018). Interpersonal communication is one domain that has attracted a lot of interest in cross-cultural studies. This work has shown that being humble, indirect, and respectful in communicating with others, as well as using honorifics is widely considered to be a common feature of East-Asian communication practices (Park & Kim, 2008; Searle, 1969; Stadler, 2011; Yum, 1988). However, the fact that Confucian ideology also highlights the importance of status differences within a society and calls attention to them has received somewhat less attention in studies of interpersonal communication (Hofstede & Bond, 1988; Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, 2010; Zhong, Magee, Maddux, & Galinsky, 2006). The aim of the present research is to fill this gap by examining status differences as a factor that can magnify or reduce cultural variations in politeness in interpersonal communication.

According to Brown and Levinson (1987), individuals use the expression of politeness strategically to manage their social relations based on a universal concern to save or support their own face and the face of others. However, politeness theory also stipulates that there are cultural differences in the use of language (Brown & Levinson, 1987). For example, the ways in which politeness is conveyed linguistically and non-linguistically may vary within East Asian cultural groups functioning as a means of status differentiation between interlocutors (e.g., Ambady, Koo, Lee, & Rosenthal, 1996; Holtgraves & Yang, 1992). To be more specific, Koreans are more affected by their interaction partner's relative status than are Americans (Holtgraves & Yang, 1992). In addition, Koreans adopt different politeness strategies depending on the status of the interaction partner (e.g., boss, peer, or subordinate), whereas Americans show more or less politeness depending on the content of the message (Ambady et al., 1996). These results suggest that Koreans draw on hierarchical differences to regulate linguistic and non-linguistic expressions of politeness in interpersonal communications.

Furthermore, previous research showed that there is some indication that East-West differences in (in)directness do not always emerge. For example, Sanchez-Burks et al. (2003) observed East-West differences in work contexts, but not in non-work contexts. In the present research, we build on this examining hierarchical differentiation as another factor that may moderate East-West cultural differences in communication style. Thus, although polite and indirect communication has typically been seen as a defining characteristic of communication styles in East Asian cultural groups in general, it may be the case that this style is more prevalent in communications with higher ranking individuals, and less prevalent in communications with lower ranking individuals (Ambady et al., 1996; Holtgraves & Yang, 1992). In addition to this prediction, we also expected East-West cultural differences in polite and indirect communication would be observed in communication with individuals in a position of high power, but not in communication with those in a position of low power. To test these two predictions, in the present study, we first examined how Koreans communicate to junior or senior individuals when declining a request. We examined this question comparatively, including British individuals whose communication we expected to vary less as a function of the status of the communication partner. Furthermore, we examined how the communication partner's status affects cross-cultural differences between Korean and British individuals in the level of politeness.

1 Culture, communication, and social hierarchy

Communication styles have been shown to vary between cultures (e.g., Hall, 1976; Gudykunst, 2001). For example, high context communication styles that are based on relational concerns and politeness principles are more likely to be observed in Asian cultures than in European cultures (Ambady et al., 1996; Kim & Wilson, 1994). In contrast, low context communication styles that entail being more dramatic, open, and precise, are more likely to be found in European cultures compared with Asian cultures (Gudykunst, 2001; Park & Kim, 2008). Korean speakers also use more ground (contextual) information than do English speakers; skipping ground information can be considered as a violation of politeness conventions in the former cultural group (e.g., Rhode, Voyer, & Gleibs, 2016; Tajima & Duffield, 2012). Consequently, East-Asian individuals are often perceived as modest, humble, face-conscious, and indirect communicators (for a review see Stadler, 2011).

However, social relations are equally critical in guiding and constraining communication in East-Asian cultures (Miyamoto & Schwarz, 2006; Pan, 2000; Scollon & Scollon, 1994, 1995; Stadler, 2011). For example, we know that communicators adopt different linguistic codes (e.g., plain, polite, honorific) and more (in)direct communication in East-Asian languages depending on the social status of the interaction partner and the context in which the communication takes place (e.g., Brew & Cairns, 2004; Brown & Levinson, 1987; Holtgraves & Yang, 1992). In contrast, in low context cultures such as North-America, the content of the communication carries more weight in how a message is delivered than the relationship between the message sender and the recipient(s) (Ambady et al., 1996; Kim & Wilson, 1994).

These differences in communication between East-Asian and North-American groups mirror the wider cultural ethos of Confucianism in East-Asia (Wu-lun or five basic relationships) according to who is expected to behave differently depending on their hierarchical standing (e.g., parent-offspring, elders-juniors, and ruler-subject; Hofstede et al., 2010). Respect for authority is an important Confucian value, and submission and obedience to authority are expected and embedded in hierarchical relationships (Zhong et al., 2006). In contrast, many Western cultures, including the United Kingdom put less emphasis on inequality in status and value egalitarianism and independence in interpersonal relationships (e.g., Hofstede, 1980, 2001; Johnson, Kulsea, Cho, & Shavitt, 2005). This cultural ethos of equality (everyone's worth is equal) as a personal worth observed in Western cultures (Anglo Saxon) can be less affected by others’ evaluation of an individual (Kim & Cohen, 2010; Kim, Cohen, & Au, 2010). Children are more likely to be treated as an equal being as soon as they are capable of acting and Western parents tend to focus on educating their child to learn how to take control of their own affairs. That is, the relationship between parents and children is more equal and independent. In addition, egalitarianism and independence is also treated as an important value in educational circumstances such as school. The parent-child role is replaced by the teacher-student role, but the basic values are carried from one to the other. In the classroom, it is possible for the students to argue with the teachers, show disapproval, and display criticism in front of the teachers (Hofstede et al., 2010). Thus, different values are emphasized in interpersonal relationships in East Asian versus Western cultural groups.

2 The present research and hypotheses

The present study examines hierarchical relations as an aspect of social context that has been found to shape communication in East-Asian cultures. As hierarchical expectations shape interpersonal relationships in Confucian high power distance countries such as Korea, we predicted Korean individuals to pay greater attention to the hierarchical position occupied by interaction partners, and regulate their communication style in line with the cultural imperatives of fitting into one's role and social context. In contrast, we expected that British individuals would not feel the need to regulate their communication as a function of the status of their interaction partners due to the more individualistic and less hierarchical (egalitarian) nature of their society (e.g., Hofstede, 2001; Kim & Cohen, 2010; Kim et al., 2010; Kitayama, Park, Sevincer, Karasawa, & Uskul, 2009; Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). This prediction is in line with the previous research (Ambady et al., 1996; Holtgraves & Yang, 1992).

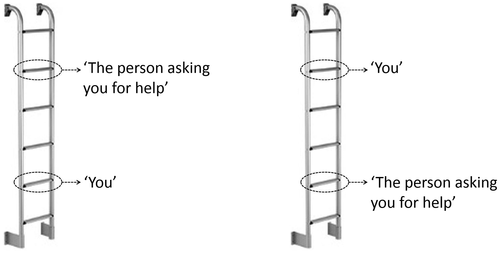

Importantly, the present work extends this previous research by testing a novel theoretical prediction. We expected that a prevalent cross-cultural assumption that the level of politeness in communication is higher among East Asians than among members of other cultural groups would be moderated by the status of the communication partner. That is, we focused on cultural group differences in polite and indirect communication between low and high status individuals. In addition, we focused on work context to investigate if there are East-West cultural differences in communication style as a result of hierarchical differentiations. As operational extensions, we manipulated relative status using a visual ladder, not relying on roles (e.g., student vs. professor), to present the hierarchical distance equally between participants and their interaction partner. We also used an indirect communication channel (i.e., email), which is a more conservative way of investigating politeness due to the lack of social context cues such as voice tone and body language messages compared to face-to-face communication channels.

Thus, we examined our predictions in the context of writing an email declining a request made by a junior person compared to a senior person, predicting that the content and style of the emails written by Korean and British individuals to decline a request would vary as a function of requester status. Specifically, we first predicted that Korean individuals would produce email content that is more polite (both subjectively and objectively in terms of the length and amount of time spent crafting the email) to decline a senior person's request compared with a junior person's request, whereas the communication style of British individuals would not vary as a function of the relative status of their interaction partner. Importantly, we predicted that Korean and British participants would differ in how polite and how much time was spent writing the email when declining a senior person's request, but they would not differ when declining a junior person's request.

1 METHOD

1.1 Participants and design

Ninety-two undergraduate students from a British university who identified themselves as White British (77 women, Mage = 19.55, SD = 3.90) and 128 Korean undergraduate students from a Korean university (83 women, Mage = 20.99, SD = 2.23) participated in a study on “managing relationships” in exchange for course credit (British) and additional points (Korean). The study employed a 2 (cultural group: Korean vs. British) × 2 (requester status: senior vs. junior) between-subjects design.

1.2 Procedure and materials

Participants completed the study using an online questionnaire in controlled settings (in the lab or in a computer room). We manipulated status by asking participants to imagine declining a request made by a senior or a junior person (see Appendix A). Written instructions were accompanied by a picture of a ladder encouraging participants to visualize the difference in status between themselves and the message recipient (Figure 1). We also matched the gender of the requester with the gender of the participant.

Next, participants were asked to write an email to the requester to decline her or his request. We recorded the start and end time of the emails written addressing the requester to measure how long participants took to write the email. Finally, participants responded to two items designed to assess their understanding of the manipulated status difference (1 = has much less power and influence than me to 7 = has much more power and influence than me; 1 = enjoys much less status and respect than me to 7 = enjoys much more status and respect than me; rUK = 0.76, p < 0.001; rKOR = 0.82, p < 0.001), and then were thanked and debriefed.

1.2.1 Dependent measures

To provide a subjective measure of politeness, we asked three raters, who were blind to the study hypotheses, to evaluate the politeness of each email using a one-item, 7-point scale (1 = not polite at all, 7 = very polite: rKOR = 0.81, p < 0.001; rUK = 0.62, p < 0.001). The raters were a native British, a native Korean, and a Korean-English bilingual individual. The emails produced by Korean participants (which were available only in Korean) were evaluated by the Korean and the bilingual rater and the emails produced by British participants (which were available only in English) were coded by the British and the bilingual rater. We then averaged the evaluated scores between the bilingual rater and the Korean rater to provide an index of politeness observed in the email content for the Korean sample. Using the same procedure, we also created an index of politeness for the British sample. To provide an objective proxy for politeness, we calculated the time participants took to write the email by subtracting the start time from the end time. Previous research has validated the use of message length and message duration as indices of politeness (see Miyamoto & Schwarz, 2006; Moon & Han, 2013).

2 RESULTS

2.1 Data preparation

We substituted six univariate outliers ( + 2.5 SD) for writing time with the next highest value in the distribution (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001).

+ 2.5 SD) for writing time with the next highest value in the distribution (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001).

2.2 Manipulation check

A 2 (cultural group: Korean vs. British) × 2 (requester status: senior vs. junior) between-subjects ANOVA conducted with the composite status score revealed a significant main effect of requester status, F(1, 216) = 249.75, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.54. As expected, the senior requester was perceived as having a higher status (M = 5.11, SD = 0.98) than the junior requester (M = 3.10, SD = 0.93). The main effect of cultural group, F(1, 216) = 1.98, p = 0.160, ηp2 = 0.01, and the cultural group X requester status interaction effect, F(1, 216) = 3.67, p = 0.057, ηp2 = 0.02, were not significant.

2.3 Dependent variables

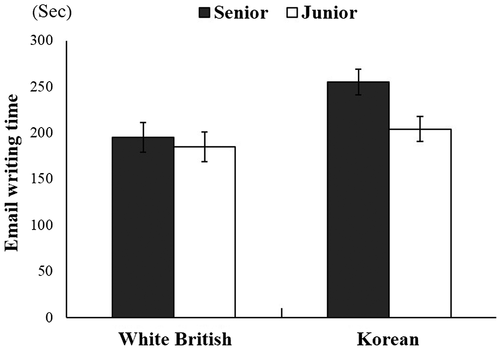

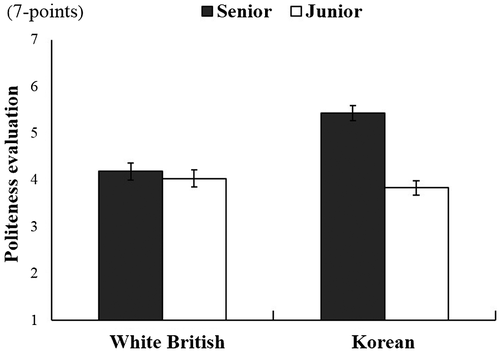

We first conducted a MANOVA with subjective (politeness ratings) and objective (the time participants took to write their email) markers of politeness as outcome variables and cultural group and requester status as the between-subjects variables. The MANOVA results revealed a significant main effect of cultural group, Wilks's λ = 0.95, F(2, 215) = 5.54, p = 0.009, ηp2 = 0.05, and requester status, Wilks's λ = 0.89, F(2, 215) = 13.48, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.11, qualified by a significant cultural group X requester status interaction effect, Wilks's λ = 0.92, F(2, 215) = 9.45, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08 (see Figures 2 and 3). Decomposing this effect revealed that the effect of requester status was significant among Korean participants, Wilks's λ = 0.73, F(2, 125) = 23.33, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.27, but not among British participants, Wilks's λ = 0.99, F(2, 89) = 0.22, p = 0.800, ηp2 = 0.01. Looking at follow-up pairwise comparisons shown in Tables 1 and 2, Korean participants, but not British participants, produced emails that were subjectively more polite and took objectively longer to craft when addressing a senior colleague compared to a junior colleague. Importantly, extending previous work, an inspection of cultural differences within each requester status condition revealed that the effect of cultural group was significant in the senior condition, Wilks's λ = 0.78, F(2, 106) = 14.57, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.22, but not in the junior condition, Wilks's λ = 0.97, F(2, 108) = 1.55, p = 0.217, ηp2 = 0.03. Again, looking at follow-up pairwise comparisons (see Table 1 and 2), Korean and British participants differed in how polite and time-consuming their emails were when declining a senior person's request, but they did not differ when declining a junior person's request.

| Measure | Korean (N = 128) | British (N = 92) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senior | Junior | Senior | Junior | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Politeness evaluation | 5.43 | 1.23 | 3.83 | 1.41 | 4.18 | 1.11 | 4.03 | 1.10 |

| Email writing time | 255.08 | 129.51 | 204.20 | 99.64 | 195.13 | 96.11 | 184.87 | 109.83 |

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | F | p raw | p adjusted | η p 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Politeness evaluation | Requester status (Senior vs. Junior) | Korean (n = 128) | 46.55 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.270 |

| British (n = 92) | 0.436 | 0.511 | 0.761 | 0.005 | ||

| Cultural group (Korean vs. British) | Senior (n = 109) | 29.42 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.216 | |

| Junior (n = 111) | 0.660 | 0.418 | 0.803 | 0.006 | ||

| Email writing time | Requester status (Senior vs. Junior) | Korean (n = 128) | 6.23 | 0.014 | 0.067 | 0.047 |

| British (n = 92) | 0.227 | 0.635 | 0.635 | 0.003 | ||

| Cultural group (Korean vs. British) | Senior (n = 109) | 7.02 | 0.009 | 0.054 | 0.062 | |

| Junior (n = 111) | 0.931 | 0.337 | 0.806 | 0.008 |

Note

- Adjusted p-values are derived using a Holm-Šidák multiplicity correction (i = 8) to counter Type 1 error inflation (Abdi, 2010).

We provide some examples of written emails obtained from Korean and British participants to illustrate cultural differences in politeness observed in the present study (see also Appendix B, Table B).

3 DISCUSSION

How individuals communicate with others in social interactions differs between cultural groups (e.g., Ambady et al., 1996; Hall, 1976; Gudykunst, 2001; Kim & Wilson, 1994). One prevalent assumption in psychology has been that East Asian individuals are generally more polite in their communications due to cultural norms and values that prescribe being respectful toward others. This is generally consistent with research findings that communications in East Asian cultures are subject to stricter politeness conventions than in Western cultures (Rhode et al., 2016; Tajima & Duffield, 2012). However, this prior research did not consider if cross-cultural differences emerge equally for communications with message recipients who occupy different ranks in the social hierarchy. Several empirical studies have demonstrated cultural differences in the effect of message recipients’ status in both linguistic and nonlinguistic communication (Ambady et al., 1996; Holtgraves & Yang, 1992), but this work did not examine cultural variations in communications with lower status interaction partners on the one hand, and cultural variations in communications with higher status interaction partners on the other hand. To provide theoretical integration and address this gap in the literature, we compared Korean and British individuals’ email communications in a (simulated) work context.

Our findings showed that, in line with common assumptions, the emails written by Korean participants were more polite and more carefully crafted than those written by British participants. However, as predicted, this general finding was moderated by communication partner's status. Korean participants, but not British participants, spent more time crafting emails that were subjectively more polite when the message addressed a senior colleague than when the message addressed a junior colleague (and there was a tendency for the emails to be longer too). These findings suggest that East-West cultural differences in communication styles can emerge when the communication partner is of higher status, but not when the communication partner is of lower status.

Moreover, the finding demonstrating that a significant effect of interaction partner's position of status among Korean participants, but not among British participants supports previous research (Ambady et al., 1996; Holtgraves & Yang, 1992). Korean participants make a clear distinction as to who they address in their communications and the politeness of their messages are shaped by this distinction, whereas for British participants the rank of the requester does not affect how they communicated to decline the request. These findings support the notion that Korean individuals put greater emphasis on relational aspects of hierarchy compared with British participants (Hofstede, 1980, 2001 ).

Interestingly, the present findings also suggest that Korean individuals occupying higher status positions can afford to use a more direct style of communication when interacting with junior message recipients. Korean participants, email communication was shorter and less polite than that of British participants only when they were asked to decline a junior person's request, but not when they were asked to decline a senior person's request. This is consistent with recent findings demonstrating that Japanese occupying a higher (vs. lower) social status express more anger (Park et al., 2013). It also dovetails work showing that it is not unusual for Koreans to expect being mistreated by senior individuals (Moon, Weick, & Uskul, 2018).

3.1 Theoretical implications

The present research contributes to a growing body of evidence showing that communication styles vary between cultures (e.g., Hall, 1976; Gudykunst, 2001). Importantly, the present work challenges the notion that East-Asian individuals are in general more modest, humble, face-conscious, and indirect communicators (for a review see Stadler, 2011). Instead, we have argued and found initial evidence that hierarchical standing moderates East-West cultural differences in the level of politeness, which points to the need to consider the role of socio-hierarchical contexts to understand cross-cultural differences in interpersonal communication. Consistent with prior research, our work highlights once more the need to take into account the specific socio-cultural context in which communication takes place to predict cross-cultural variations in communication styles (e.g., Ambady et al., 1996; Holtgraves & Yang, 1992). In this view, broad-sweeping, main-effect predictions may not be adequate to capture the intricacies of rich socio-cultural contexts that characterize human interactions.

The present research could explain previous findings demonstrating that East-West cultural differences in conversational indirectness are more prominent in work contexts compared with non-work contexts (Sanchez-Burks et al., 2003). Hierarchical differentiations are more formally defined in work (vs. non-work) contexts via the use of official titles, responsibilities and power. In contrast, non-work contexts are more commonly shared with peers and respondents may have thought about interactions with equal status individuals in previous studies. In other words, the present findings could help explain why East-West cultural differences in communication styles are more likely to emerge in some contexts than in others.

3.2 Strengths, limitations, and directions for future research

The present research is strengthened by using a comparative approach, sampling participants from both Korean and British populations and both objective and subjective measures of the constructs of interest. Finally, unlike previous studies, we manipulated relative status aided by a visual ladder, thereby going beyond previous studies that relied on roles (e.g., student vs. professor) to manipulate relative status (e.g., Ambady et al., 1996; Holtgraves & Yang, 1992). Although this manipulation check would suggest that there were no differences in the level of seniority between Korean and British participants’ perceptions, we also acknowledge that Korean and British participants might not have recalled the same people in the experiment due to the cultural differences in the level of importance of status differences between Korean and British societies.

Several limitations of the present research offer opportunities for future studies. First, we demonstrated cultural differences in politeness by focusing on the dynamics of hierarchical differentiation in interpersonal relationships among individuals who share the same ethnic background and cultural values within each cultural setting. However, individuals also interact with people from different cultural backgrounds within or across cultural settings. For example, studies on intercultural email communication in English between Australian and Korean academics show that Koreans use titles more frequently than Australians do, and Koreans also report feeling uncomfortable when they were addressed by their first name (Murphy & Levy, 2006). The present research could be usefully extended by examining inter-cultural communications with lower and higher ranking individuals.

Second, one important question that the current study cannot address is whether the observed differences are due to features of the Korean and British language, or more due to more profound cultural differences that are inherent in culturally shared meanings, beliefs, and practices. For example, it would be interesting to see if a similar pattern of cultural group differences and similarities would be observed if Korean individuals are asked to decline a request in English (as opposed to Korean), or vice versa for British individuals. If linguistic features account for the present findings, Koreans could be expected to show a lower level of sensitivity to hierarchies in interpersonal communications when using English compared with when using Korean (and vice versa for British individuals).

Third, although we attribute the observed differences between the cultural groups to the Confucian ideology prevalent in the Korean context, we do not directly assess this. Future research should investigate more closely the culturally shaped reasons for these differences. In addition, we have made repeated reference to East-Asian countries, specifically China, Korea, and Japan. However, some might argue that these countries differ in terms of how much Confucianism has shaped present-day cultural values and beliefs. Nevertheless, there is evidence that these countries’ values and social interaction patterns are shaped by Confucianism (e.g., Baker, 2016; Winfield, Mizuno, & Beaudoin, 2000). Future research is required to establish whether the present findings extend to other cultural contexts in West and East Asia.

Finally, the present findings can provide a meaningful insight for other domains of comparative research such as creativity and subjective well-being. First, previous research on creativity has mostly compared the main effect of hierarchical differentiation separately for Eastern and Western cultural groups (high vs. low power distance) (see Erez & Nouri, 2010, for a review; George & Zhou, 2001; Oldham & Cummings, 1996). In more hierarchical societies with high power distance such as Korea, the presence of the boss at the workplace has important implications for the behaviors of subordinates. For example, the subordinates’ level of self-expression can differ depending on the presence of their boss due to the restriction of freely presenting their ideas and the need to follow their guidelines. In contrast, in less hierarchical societies with low power distance such as the United Kingdom, subordinates are less likely to be affected by the presence of supervisors when expressing their unique ideas and proving their competence (see Erez & Nouri, 2010; Hofstede, 2001; Huang, Van de Vliert, & Van der Vegt, 2005). Recently, Erez and Nouri (2010) proposed the relationship between cultural value (e.g., power distance) and creativity can be moderated by the socio-hierarchical context (working in the presence of the boss vs. working alone). However, this proposition did not take into account the effect of the individual's status. Based on the new theoretical approach of the present research, we therefore propose that future research could look into establishing the cultural differences in creativity, considering both low and high positions of power in social interactions in work contexts.

Furthermore, studies on subject well-being (SWB) have shown cultural differences between Eastern and Western cultural groups. In comparison with Westerners, Easterners have a lower level of perceived SWB (e.g., Kitayama, Markus, & Kurokawa, 2000; Oishi, Diener, Lucas, & Suh, 1999). A recent study has found a possible explanation for the East-West cultural difference stemming from different perspectives on the perceived meanings of life events regarding other's evaluation and approval between Easterners and Westerners, which revealed that Taiwanese participants showed lower levels of perceived SWB but higher levels of need for receiving approval from others than American participants (Liu, Chiu, & Chang, 2017). Given that hierarchical relationships as an aspect of social contexts are considered more important in East Asian than Western countries (Hofstede et al., 2010; Triandis & Gelfand, 1998), this study could be further established by specifying the status of others in everyday interactions in work contexts.

3.3 Conclusion

In conclusion, the present research demonstrates that hierarchical relations dictate the politeness of Korean individuals’, but not British individuals’, communication styles. Importantly, evidence for greater politeness in Korean (vs. British) individuals was only found in communications with senior individuals, but not in communications with junior individuals. This suggests that hierarchical relations are important to provide a fuller and a more complete understanding of cultural differences in politeness.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Jaechang Bae for his assistance with data collection from South Korea.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

CM conducted the experimental research and performed the data analysis. All authors discussed the results. CM wrote the first draft of the manuscript and AKU and MW provided comments and made critical revisions. AKU and MW contributed equally to the manuscript.

APPENDIX A:

Email task instructions:

Imagine that you received an email from a junior [or senior] person who knows you well and is of the same sex as you. In the email, s/he asks you to write a character reference letter for her/him. However, you are very busy due to an essay and a group project, therefore you attempt to decline her/his request.

APPENDIX B:

Table B Comparing Korean and British participants’ written email responses

| Korean participants | British participants | |

|---|---|---|

| Senior (1) |

|

|

| Junior (1) |

|

|

| Senior (2) |

|

|

| Junior (2) |

|

|

Note. Senior (1) and Junior (1) cases indicate the higher level of subjective politeness (higher than the scale midpoint = 4). Senior (2) and Junior (2) cases indicate the lower level of subjective politeness (lower than the scale midpoint = 4). It is important to note that both polite and impolite email responses can of course be found in each condition of cultural group and requester status. Interestingly, we also observed instances in which individuals in a position of high power can also use honorifics in their communication with lower status individuals in the Korean sample (see junior 1 case in Table B). Although this reversed use of honorifics was not very common, it highlights the importance of individual differences as a factor that also contributes to variations in politeness.