Recategorization and ingroup projection: Two processes of identity uncertainty reduction

Abstract

Four experiments, conducted in South Korea and Scotland, drew on uncertainty–identity theory to investigate how recategorization and ingroup projection interplay to maintain a clear, certain sense of identity in people's hierarchy of self-categorizations. Experiment 1 (N = 74) found that people who were made to feel uncertain about a subgroup identity that was central to their self-concept, identified more strongly with and felt more certain about their superordinate identity (H1). In Experiment 2 (N = 70), people were made to feel uncertain about their superordinate identity. Where ingroup projection was low, people also felt uncertain about their subgroup identity (H2). However, when ingroup projection was high, they did not feel uncertain about their subgroup identity (H3). These two experiments support our proposition that uncertainty at the subgroup and the superordinate level can be restored by recategorization and ingroup projection. Experiments 3 and 4 (Ns = 91 and 67) converge to show that when people were uncertain about both superordinate and subgroup identity, they resolved this dual uncertainty by enhancing perceived entitativity of the most central group. If the subgroup was more central, they increased support for subgroup separation so that the subgroup had a clear boundary whereas if the superordiate group was more central, they increased support for integration so that the superordinate group could be a cohesive entity without internal fragmentation (H4). The findings are discussed in terms of group resilience in the face of social change and uncertainty.

1 INTRODUCTION

Knowing who we are is fundamental for adaptive social behavior (Baumeister, 1998). One important source of self-knowledge and social identity is the groups we belong to and identify with (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). However, social identity is not always clearly defined—it can change over time or there may be intragroup disagreement over the group's identity. Often, group norms and identity are not fully disclosed to newcomers. When we don't know who we are and how we are socially located in the world, we cannot effectively plan our actions or predict others' actions. Because the self-concept is structured, such that more or less distinct and more or less self-conceptually central identities are hierarchically nested within identities (Crisp & Hewstone, 2007; Turner, 1985), identity uncertainty can be experienced and resolved at different levels of self-categorization. Uncertainty-identity dynamics are both complex and fluid.

To understand this dynamic, we focus on three processes; (a) how identity uncertainty at one level of self-categorization influences uncertainty at a lower or higher level of self-categorization, (b) how this generates recategorization-based identification at a subgroup or superordinate level of categorization, and (c) how ingroup projection reduces uncertainty spillover, particularly from superordinate to subgroup level, and enables subsequent recategorization.

Building on uncertainty–identity theory (Hogg, 2012; Hogg, Sherman, Dierselhuis, Maitner, & Moffitt, 2007)—a theory that attributes self-uncertainty reduction a motivational role in group identification, we argue that the locus of uncertainty (subgroup or superordinate group identity) influences the level of self-category at which people recategorize themselves. Such that subgroup identity uncertainty can be compensated for by perceiving one's superordinate identity as certain and recategorizing oneself at the superordinate level. However, superordinate identity uncertainty cannot so easily be compensated for by recategorizing oneself at the subgroup level—this is because the superordinate identity encompasses the subgroup and thus superordinate identity uncertainty can generate subgroup identity uncertainty. Although there are a couple correlational studies that provide partial evidence for this asymmetry of compensatory responses (Jung, Hogg, & Choi, 2016; Jung, Hogg, & Lewis, 2018), no research has investigated the causal direction nor the degree to which uncertainty at one level might affect uncertainty at the other level.

Another novelty of this paper is its focus on the uncertainty reduction effect of ingroup projection in the face of superordinate identity uncertainty. Ingroup projection is a process whereby people project their own subgroup's attributes onto a superordinate group and thus view the superordinate group as possessing their own subgroup's attributes (Mummendey & Wenzel, 1999; Wenzel, Mummendey, & Waldzus, 2007). We argue that although superordinate identity uncertainty may impart uncertainty to its nested subgroup identity, ingroup projection can restore a sense of certainty by projecting subgroup identity onto a superordinate level.

In sum, we argue that people can have a clear sense of identity through recategorization and ingroup projection. As such, the hierarchical system of self-categorization can be resilient under uncertainty. We conducted four experiments, in the Korean peninsula and in Scotland within the United Kingdom—in both places people have a dual identity such that a subgroup identity is nested within a superordinate identity.

1.1 Self-categorization, depersonalization, and uncertainty reduction

Social identity theory and self-categorization theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987; also see Abrams & Hogg, 2010) explain that people cognitively organize their complex social world into fewer, hierarchical categories, and they derive a sense of identity from the social categories and groups they identify with. A group is represented as a prototype—a fuzzy set of attributes that describe and prescribe who we are, how we should feel, think, and behave. When people categorize themselves and others into a group, they assign a group prototype to themselves and others. In this way, self and others are perceived as interchangeable members of an ingroup. Once the group prototype is internalized into self-concept, it forms social identity—a process of depersonalization.

Self-categorizations are organized into a hierarchical system of classification (Turner, 1985; Turner et al., 1987). A particular category is entirely included and nested within a higher-level, more abstract, and inclusive category. Although Turner and his associates specified three important levels of self-categorization from the most inclusive human category through the intermediate ingroup–outgroup categorization to the lowest level personal self-categorization, he also addressed that there are numerous specific self-categorizations at each level of abstraction. He noted that a lower-level self-category is evaluated as members of its higher-level self-category (Turner, 1985, p. 96). As people are depersonalized as members of an ingroup and defined in terms of ingroup prototype, subgroups are depersonalized as members of an inclusive superordinate group and defined in terms of superordinate prototype. This superordinate-to-subgroup depersonalization process results in the perception that one's subgroups and other subgroups are more or less interchangeable member-groups which share the superordinate group attributes.

Uncertainty–identity theory (Hogg, 2000, 2007, 2012) describes how self-uncertainty motivates self-categorization processes. According to uncertainty–identity theory, a feeling of uncertainty is aversive―particularly when people feel uncertain about important dimensions of their self-concept. People are therefore motivated to reduce uncertainty and restore a sense of certainty. Identification with a group can resolve uncertainty because a group prototype, once internalized as a form of social identity, provides self-definition. Highly entitative groups with clearly defined prototypical attributes are best suited to uncertainty reduction.

Research has provided ample empirical support for uncertainty–identity theory (see Hogg, 2012). When people are uncertain about themselves, they identify with groups, especially highly entitative groups (Grant & Hogg, 2012; Sherman, Hogg, & Maitner, 2009) and disidentify from low entitative groups or uncertainty-inducing groups (Hogg, Adelman, & Blagg, 2010; Hogg, Meehan, & Farquharson, 2010; Hogg et al., 2007). Directly relevant to the present research, two correlational studies (Jung et al., 2016, 2018) found a puzzling asymmetry in the relationship between identity-uncertainty and recategorization in the context of hierarchial identities. When people are uncertain about a subgroup which is central to their self-concept, they recategorize and identify more strongly with a superordinate group; however, uncertainty about a superordinate group was not associated with subgroup identification.

We argue that this asymmetry may be attributed to the top-down nature of depersonalization. In depersonalization, a higher-level self-categorization defines a lower-level self-categorization and reduces uncertainty at the lower-level identity. As group identification reduces self-uncertainty (Hogg, 2012), superordinate identification can reduce subgroup identity uncertainty. However, the same depersonalization process can also spread uncertainty if the locus of uncertainty is at a higher level. Because a superordinate identity encompasses subgroups nested within it, superordinate identity uncertainty can readily create subgroup identity uncertainty. This uncertainty spillover may prevent people from recategorizing themselves at the subgroup level.

This reasoning generates two key hypotheses. When people feel uncertain about a subgroup identity that is central to their self-concept, they compensate for subgroup identity uncertainty by perceiving their superordinate identity as more certain and recategorize themselves into and identify more strongly with the superordinate group (H1). However, if people feel uncertain about their superordinate identity, this carries over to their subgroup identity—people feel uncertain about subgroup identity and cannot recategorize themselves into or identify more strongly with the subgroup (H2).

1.2 Ingroup projection

According to the ingroup projection model, people sometimes project their own subgroup traits onto an inclusive superordinate group (Mummendey & Wenzel, 1999; Wenzel et al., 2007). When this happens, people come to view the superordinate group as possessing their own subgroup attributes to a greater extent than other subgroups' attributes. Ingroup projection is defined as “the perception, or claim, of the ingroup's greater relative prototypicality for the superordinate group” (Wenzel, et al., 2007, p. 337). From this logic, a relative ingroup prototypicality (RIP) scale has been used to measure ingroup projection. In contrast to depersonalization which fosters perceived interchangeability among subgroups, ingroup projection increases the relative prototypicality of one's own subgroup compared to other subgroups. Subsequently, ingroup projection marginalizes other subgroups (Bianchi, Mummendey, Steffens, & Yzerbyt, 2010; Wenzel, Mummendey, Weber, & Waldzus, 2003).

Ingroup projection is particularly prominent among high-status subgroup. For example Mummendey and her colleagues have shown that high-status subgroups (e.g., West Germans) project their own characteristics onto the superordinate group (Germans) and regard the other subgroup (e.g., East Germans) as deviating from the superordinate prototype projected from their own subgroup (Waldzus, Mummendey, Wenzel, & Weber, 2003; Wenzel et al., 2003).

Because ingroup projection exacerbates ingroup bias and exclusion of other subgroups, recent research has focused on conditions which diminish ingroup projection rather than amplify it. Ingroup projection is suppressed when people recognize that there are diverse other subgroups that equally well define the superordinate category (Waldzus, Mummendey & Wenzel, 2005; Waldzus et al, 2003) or when people have a clear and well-defined understanding of the similarities and differences among subgroups within a superordinate category (Peker, Crisp & Hogg, 2010).

In contrast to the top-down nature of depersonalization, ingroup projection is a bottom-up process whereby subgroups' attributes define a superordinate group and thus can reduce uncertainty at a superordinate level. Therefore, we argue that if people engage in ingroup projection, this counteracts the uncertainty spillover from superordinate to subgroup levels predicted under H2. As a result, recategorization of self into one's subgroup can be a viable way for people to reduce superordinate uncertainty (H3).

1.3 Overview

We tested our analyses in the geopolitical context of the Korean peninsula and the issue of reunification of North and South Korea. South Koreans have a dual identity in which South Korean identity is nested within an overarching ethnic Korean identity. We conducted two pairs of studies. Experiments 1 and 2 tested our three key hypotheses. Experiment 1 manipulated uncertainty at the subgroup South Korean level and tested if people would strengthen superordinate ethnic Koran identification and feel certain about superordinate identity (H1). Experiment 2 manipulated uncertainty at the superordinate ethnic Korean level and tested if superordinate identity uncertainty would spill over to subgroup identity (H2) and whether ingroup projection can reduce this uncertainty spillover effect and result in increased subgroup identification (H3). Besides, we also measured attitude toward reunification and support for reunification policies to explore the possible geopolitical consequence of uncertainty-recategorization dynamics. Experiments 3 and 4 explored how people would respond when they feel uncertain about their supeordinate and subgroup identity simultaneously. We will overview Experiments 3 and 4 at the start of Experiment 3.

2 EXPERIMENT 1

Experiment 1 tested H1, that when people feel uncertain about a subgroup identity that is central to their self-concept, they strengthen superordinate identification and feel certain about their superordinate identity. We also explored how this process would change people's intentions relating to inter-subgroup integration. For exploratory purpose, we measured RIP (the measure of ingroup projection) although we predicted there would be no significant effect of ingroup projection on the dynamics of subgroup identity uncertainty and superordinate identification.

2.1 Method

2.1.1 Participants and design

Seventy-four introductory psychology students from a private university in Seoul, South Korea participated in exchange for course credit (41 female, 33 male; 18–28 years of age around a mean of 20.84 years). Thirty-six participants were randomly assigned to the low subgroup identity uncertainty condition and 38 participants to the high subgroup identity uncertainty condition. Given the design of the study, this sample size would yield 84% power to detect a medium-sized effect (f2 = 0.15).

2.1.2 Procedure

Participants entered a laboratory and were told that the research concerned how South Koreans' ethnic and national identities influence their thoughts, feelings, and attitudes toward sociopolitical issues. They completed a questionnaire, written in Korean by a researcher fluent in both Korean and English, which incorporated instructions, manipulations, and measures. The questionnaire included four items measuring relative identity centrality, the manipulation of subgroup identity uncertainty, three items checking on the manipulation of subgroup identity uncertainty, five items measuring superordinate identity uncertainty, and three items measuring superordinate identification. Because centrality had already been measured as a moderator, the identification items did not include any measures of centrality (Cameron, 2004; Leach et al., 2008). We also measured general attitude toward North–South Korean reunification and support for three policies relating to North–South Korea reunification. Finally, participants provided demographic information including age, gender, and political orientation, and were thanked and debriefed. We report all measures and manipulations below.

Relative identity centrality

How central participants' subgroup identity to their self-concept relative to superordinate identity was constructed by subtracting superordinate identity centrality from subgroup identity centrality. Superordinate identity centrality was measured with a two-item centrality scale (Cameron, 2004). Questions were “I feel that being ethnic Korean is important part of my self-image” and “I often think about the fact that I am ethnic Korean.” (1 strongly disagree, 9 strongly agree); r = 0.70, p < 0.001. Subgroup identity centrality was measured in the same manner with two items, r = 0.74, p < 0.001.

Relative ingroup prototypicality

The degree of ingroup projection was measured by a reliable RIP scale (Waldzus, Mummendey, Wenzel, & Boettcher, 2004) which determined the extent to which participants perceived South Koreans to be more prototypical/representative of ethnic Koreans relative to North Koreans. Participants were asked to generate three traits they believed were characteristics of their subgroup (South Koreans) and the other subgroup (North Koreans), and then rated how much each of these traits applied to members of the superordinate category (ethnic Koreans), 1 not at all, 9 very much. Mean scores for each subgroup on these items gave an index of how prototypical the members of this subgroup were judged to be of ethnic Koreans in general. The difference between the scores for the South Korean ingroup (α = 0.76) and the North Korean outgroup (α = 0.74) constituted the index of RIP.

Subgroup identity uncertainty manipulation

Subgroup identity uncertainty was manipulated by a priming method closely based on previous uncertainty–identity theory studies (e.g., Gaffney, Rast, Hackett, & Hogg, 2014; Grant & Hogg, 2012; Hogg, Meehan et al., 2010) Participants in the high subgroup identity uncertainty condition were asked to think about and write down two aspects of South Korea and South Koreans that make them feel uncertain in defining who they are as South Korean. Participants in the low subgroup identity uncertainty condition were asked to think about and write down two aspects of South Korea and South Koreans that make them feel certain in defining who they are as South Korean.

Manipulation check

Manipulation of subgroup identity uncertainty was checked with three items adapted from Jung et al. (2016). Participants indicated how much they felt each of these states when they thought of who they were as South Koreans at that time on a semantic differential scale (−4 uncertain, unclear, unsure, 4 certain, clear, sure), α = 0.94.

Superordinate identity uncertainty

The extent to which participants felt uncertain about their superordinate identity was measured with five items adapted from Jung et al. (2018). Participants indicated how well each of five statements described their feelings about ethnic Korean identity at that time: “I am uncertain about who we the ethnic Korean really are,” “When I think about who we the ethnic Korean are, I am unsure that the ethnic Korean identity that I know is correct,” “When I think about who ethnic Koreans were in the past, I don't know what ethnic Koreans were really like,” “When I think about who ethnic Koreans are, the image of ethnic Korean people in my mind is unclear,” and “If I were asked to describe who ethnic Korean people are, my description might end up being ambiguous,” 1 not at all, 9 very much, α = 0.90.

Superordinate identification

Strength of superordinate identification with being ethnic Korean was measured with three items adapted from previous social identity research (e.g., Hogg & Hains, 1996). Participants indicated how well they felt they fit in with other ethnic Koreans, how strongly they felt they identified as being ethnic Korean, and how strongly they would stand up for ethnic Koreans if they were criticized, 1 not at all, 9 very much, α = 0.79.

Superordinate integration

Participants' general attitude toward superordinate integration was measured with one item: “How much do you support North-South Korea reunification?”, 1 not at all, 9 very much.

Participants were presented with three well-known policies relating to reunification of North and South Korea: Exchange visits of separated families, cultural exchange, and development of unified, unabridged Korean language dictionary. Participants indicated their support for each policy, 1 not at all, 9 very much, α = 0.80.

2.2 Results

2.2.1 Descriptive and demographic analyses

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of the six scales are presented in Table 1. Gender composition, age, and political orientation did not differ significantly across conditions ( , Fs < 1).

, Fs < 1).

2.2.2 Relative identity centrality

A one-way within-subjects ANOVA revealed that participants' subgroup identity (M = 5.95, SD = 1.88) was significantly more central than their superordinate identity (M = 4.44, SD = 1.81), F (1, 73) = 44.04, p < 0.001,  = 0.38. Thus, we constructed relative centrality by subtracting superordinate identity centrality from subgroup identity centrality. Relative centrality was ranged from −3.00 to 8.00 (M = 1.51, SD = 1.96). Higher scores indicate that subgroup identity was more central to their self-concept than superordinate identity, lower scores that superordinate identity was similarly or more central than subgroup identity.

= 0.38. Thus, we constructed relative centrality by subtracting superordinate identity centrality from subgroup identity centrality. Relative centrality was ranged from −3.00 to 8.00 (M = 1.51, SD = 1.96). Higher scores indicate that subgroup identity was more central to their self-concept than superordinate identity, lower scores that superordinate identity was similarly or more central than subgroup identity.

2.2.3 Manipulation check

We submitted the manipulation check to hierarchical regression analyses. Subgroup identity uncertainty (0 = certain, 1 = uncertain) and relative identity centrality (continuous) were included in Step 1 as predictors, and the subgroup identity uncertainty x relative identity centrality interaction was included in Step 2. The main effect of subgroup identity uncertainty manipulation was significant, b = −1.12, SEb = 0.48, t(71) = −2.35, p = 0.021. The main effect of relative identity centrality was also significant, b = 0.26, SEb = 0.12, t(71) = 2.10, p = 0.039. We found a two-way interaction at a marginally significant level, b = 0.47, SEb = 0.24, t(70) = 1.94, p = 0.057. People for whom subgroup was not so central to their self-concept reported they felt uncertain about subgroup identity significantly greater when they were made to feel uncertain (vs. certain) in their subgroup identity, b = −2.04, SEb = 0.67, t(70) = −3.06, p = 0.003. Whereas, people for whom subgroup was central to their self-concept did not differ in their reported uncertainty about subgroup identity, b = −0.19, SEb = 0.67, t(70) = −0.29, p = 0.771.

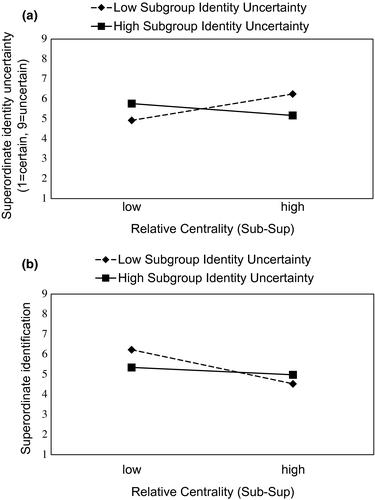

2.2.4 Superordinate identity uncertainty

We submitted superordinate identity uncertainty to the same analysis. The main effects of subgroup identity uncertainty and relative centrality were not significant, b = −0.12, SEb = 0.37, t(71) = −0.32, p = 0.749; b = 0.05, SEb = 0.10, t(71) = 0.50, p = 0.615. As predicted, we found a significant two-way interaction, b = −0.49, SEb = 0.19, t(70) = −2.61, p = 0.011 (Figure 1a). Consistent to our prediction (H1), people for whom subgroup was central reported significantly lower uncertainty about superordinate identity when they were made to feel uncertain (vs. certain) in their subgroup identity, b = −1.08, SEb = 0.51, t(70) = −2.10, p = 0.039. Whereas, people for whom subgroup was not so central did not differ in their reported uncertainty about superordinate identity, b = 0.84, SEb = 0.51, t(70) = 1.63, p = 0.107. Put differently, in the low subgroup identity uncertainty condition, relative identity centrality was significantly associated with a high level of superordinate identity uncertainty, b = 0.34, SEb = 0.14, t(70) = 2.34, p = 0.022. Whereas, in the high subgroup identity uncertainty condition, relative identity centrality was not significantly associated with superordinate identity uncertainty, b = −0.15, SEb = 0.12, t(70) = −1.27, p = 0.208.

2.2.5 Superordinate identification

We submitted superordinate identification to the same analysis. The main effect of subgroup identity uncertainty was not significant, b = −0.21, SEb = 0.34, t(71) = −0.62, p = 0.536. The main effect of relative centrality was significant, b = −0.23, SEb = 0.09, t(71) = −2.64, p = 0.010; such that people for whom subgroup identity was more central than superordinate identity identified less strongly with superordinate identification. As predicted, a two-way interaction was marginally significant, b = 0.34, SEb = 0.18, t(70) = 1.93, p = 0.058 (Figure 1b). Consistent to our prediction (H1), people for whom subgroup was less central decreased superordinate identification when they were made to feel uncertain (vs. certain) about subgroup identity at a marginally significant level, b = −0.88, SEb = 0.48, t(70) = −1.82, p = 0.073. In contrast, people for whom subgroup was central increased superordinate identification when they were made to feel uncertain (vs. certain) about subgroup identity but this effect was not significant, b = 0.45, SEb = 0.48, t(70) = 0.93, p = 0.354. Put differently, in the low subgroup identity uncertainty condition, relative identity centrality was significantly associated with a low level of superordinate identification, b = −0.43, SEb = 0.13, t(70) = −3.21, p = 0.002. Whereas, in the high subgroup identity uncertainty condition, relative identity centrality was not significantly associated with superordinate identification, b = −0.09, SEb = 0.11, t(70) = −0.41, p = 0.409.

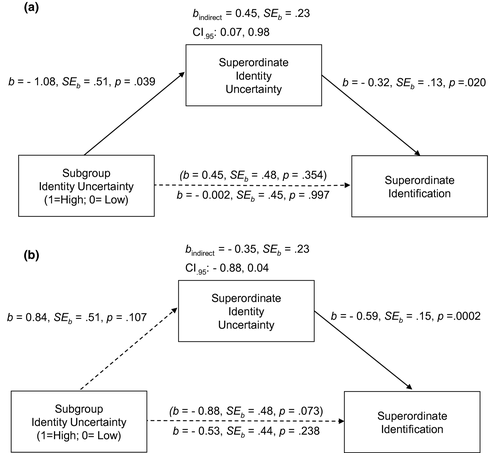

Moderated mediation analysis (Hayes' PROCESS model 8) indicated that a two-way interaction on superordinate identification was mediated by superordinate identity uncertainty, b = 0.20, SEb = 0.09, CI0.95:0.07, 0.42. Further, the effect of subgroup identity uncertainty on increased superordinate identification among people who had a central subgroup identity was mediated by decreased superordinate identity uncertainty, b = 0.45, SEb = 0.23, CI0.95:0.07, 0.98 (Figure 2a). As predicted, however, this indirect effect was not significant among people for whom subgroup identity was less central, b = −0.35, SEb = 0.23, CI0.95: −0.88, 0.04 (Figure 2b).

2.2.6 Superordinate integration

We submitted integration attitude to the same analysis. The main effects of subgroup identity uncertainty and relative centrality were not significant, b = −0.06, SEb = 0.52, t(71) = −0.11, p = 0.910; b = −0.07, SEb = 0.13, t(71) = −0.50, p = 0.618. A two-way interaction was significant, b = 0.66, SEb = 0.26, t(70) = 2.53, p = 0.014. People for whom their subgroup was not so central reported a weaker integration attitude when they were made to feel uncertain (vs. certain) about subgroup identity—the effect was marginally significant, b = −1.35, SEb = 0.71, t(70) = −1.89, p = 0.062. In contrast, people for whom their subgroup was highly central reported a strengthened integration attitude—again the effect was marginally significant, b = 1.23, SEb = 0.71, t(70) = 1.73, p = 0.088. Put differently, in the low subgroup identity uncertainty condition, relative identity centrality was significantly associated with a low level of integration attitude, b = −0.45, SEb = 0.20, t(70) = −2.28, p = 0.026. Whereas, in the high subgroup identity uncertainty condition, relative identity centrality was not significantly associated with integration attitude, b = 0.20, SEb = 0.17, t(70) = 1.23, p = 0.224.

Moderated mediation analysis revealed that a two-way interaction on integration attitude was not mediated by superordinate identity (un)certainty, b = 0.12, SEb = 0.10, CI0.95: −0.02, 0.40. Further, the indirect effect of subgroup identity uncertainty on increased support for integration via superordinate identity uncertainty was not significant among those who had central subgroup identity, b = 0.27, SEb = 0.26, CI0.95: −0.04, 1.00 as well as those whose subgroup identity was less central, b = −0.21, SEb = 0.20, CI0.95: −0.84, 0.03.

2.2.7 Integration intention

We submitted integration intention to the same analysis. The main effect of subgroup identity uncertainty was not significant, b = 0.20, SEb = 0.35, t(71) = 0.58, p = 0.563. The main effect of relative centrality was significant, b = −0.18, SEb = 0.09, t(71) = −2.05, p = 0.044; such that people for whom their subgroup identity was more central than their superordinate identity reported stronger integration intention. A two-way interaction was significant, b = 0.52, SEb = 0.17, t(70) = 3.06, p = 0.003. People for whom subgroup identity was not so central decreased their integration intention when they were made to feel uncertain (vs. certain) about subgroup identity at a marginally significant level, b = −0.82, SEb = 0.47, t(70) = −1.76, p = 0.083. In contrast, people for whom subgroup identity was highly central significantly increased their integration intention when they were made to feel uncertain (vs. certain) about subgroup identity, b = 1.23, SEb = 0.46, t(70) = 2.62, p = 0.011. Put differently, in the low subgroup identity uncertainty condition, relative identity centrality was significantly associated with a low level of integration intention, b = −0.49, SEb = 0.13, t(70) = −3.74, p = 0.0004. Whereas, in the high subgroup identity uncertainty condition, relative identity centrality was not significantly associated with integration attitude, b = 0.03, SEb = 0.11, t(70) = 0.30, p = 0.767.

Moderated mediation analysis revealed that a two-way interaction on integration intention was mediated by superordinate identity uncertainty, b = 0.11, SEb = 0.07, CI0.95:0.01, 0.29. Further, the effect of subgroup identity uncertainty on increased support for reunification policies among those who had central subgroup identity was mediated by decreased superordinate identity uncertainty, b = 0.24, SEb = 0.17, CI0.95:0.01, 0.70. However, this indirect effect was not significant among those for whom their subgroup identity was less central, b = −0.19, SEb = 0.16, CI0.95: −0.65, 0.01.

2.2.8 Ingroup projection

For exploratory purpose, we conducted a hierarchical regression with relative centrality (continuous), RIP (continuous), and subgroup identity uncertainty (0 = certain, 1 = uncertain) as predictors. All other main and high-order effects of RIP on superordinate identity uncertainty, superordinate identification, and integration were not significant, ps > 0.11; however, a three-way interaction on integration intention was significant, b = 0.20, SEb = 0.09, t(66) = 2.27, p = 0.027. Simple slopes analyses indicated that under high RIP, people who felt uncertain about subgroup identity, and felt the subgroup was more important than the superordinate group, reported increased support for integration policies with increasing subgroup identity uncertainty In contrast, people for whom subgroup identity was less important than superordinate identity decreased integration policy support.

A two-way interaction of relative centrality and subgroup identity uncertainty on the key-dependent variables remained significant or marginally significant after relative ingroup prototypicaltiy was included in the regression model, 0.002 < ps < 0.077. In summary, when people felt uncertain about a subgroup identity that was central to their self-concept, recategorization into the superordinate group occurred, regardless of whether the subgroup was more or less prototypical than the other subgroups of the superordinate group.

3 EXPERIMENT 2

Experiment 1 supported H1 and showed how uncertainty at a subgroup identity was compensated for by superordinate identification. Results indicated that subgroup identity uncertainty that was central to one's self-concept increased the certainty perception of superordinate identity and strengthened superordinate identification. Experiment 2 tested whether and how uncertainty at a superordinate identity may not be compensated for by subgroup identity. We manipulated uncertainty at a superordinate level. We predicted that manipulated superordinate uncertainty would carry over to subgroup identity, thus people would also become uncertain about their subgroup (H2); However, people who chronically engaged in ingroup projection would not feel uncertain about their subgroup when they were made to feel uncertain about their superordinate group, thus strengthening subgroup identification (H3).

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants and design

Seventy-two introductory psychology students from the same university in Seoul, South Korea participated in exchange for course credit. Thirty-seven participants were randomly assigned to the low superordinate identity uncertainty condition and thirty-five participants to the high superordinate identity uncertainty condition. Seventy participants (38 female, 32 male; 18–26 years of age; mean of 20.79 years) were included in the analysis after removal of two participants with significant missing data. Given the design of the study, this sample size would yield 76% power to detect a medium-sized effect (f2 = 0.15). In addition to exclusions of power analysis, we report all measures and manipulations below.

3.1.2 Procedure

The procedure was identical to Experiment 1 except that we manipulated superordinate identity uncertainty and measured subgroup identity uncertainty and subgroup identification, and that we also measured RIP before manipulation as a moderator.

Relative identity centrality

How central participants' subgroup identity to their self-concept relative to superordinate identity was measured and constructed in the same manner as Experiment 1 by subtracting superordinate identity centrality (r = 0.74, p < 0.001) from subgroup identity centrality (r = 0.72, p < 0.001).

Relative ingroup prototypicality

The degree of ingroup projection was measured in exactly the same way as in Experiment 1. We computed two scores—how prototypical South Koreans were perceived to be of ethnic Koreans (α = 0.81) and how prototypical North Koreans were perceived to be of ethnic Koreans (α = 0.83). Then, the difference between the scores for the ingroup and the outgroup constituted the index of RIP.

Superordinate identity uncertainty manipulation

Superordinate identity uncertainty was manipulated by a priming procedure. Participants in the high superordinate identity uncertainty condition were asked to think about and write two aspects of ethnic Koreans that make them feel uncertain in defining who they are as ethnic Koreans. Participants in the low superordinate identity uncertainty condition were asked to think about and write two aspects of ethnic Koreans that make them feel certain in defining who they are as ethnic Koreans.

Manipulation check

The manipulation of superordinate identity uncertainty was checked by asking participants to indicate on a semantic differential scale (−4 uncertain, unclear, unsure, 4 certain, clear, sure) how much they felt each of the states when they thought of who they were as ethnic Korean in the previous task, α = 0.94.

Subgroup identity uncertainty

The extent to which participants felt uncertain about subgroup identity was measured with the five items in the same manner as superordinate identity uncertainty was measured in Experiment 1. Participants indicated how well each of five statements described their feelings about South Korean identity at that time (e.g., “I am uncertain about who we the South Korean really are,” “When I think about who we the South Korean are, I am unsure that the South Korean identity that I know is correct.”), 1 not at all, 9 very much, α = 0.92.

Subgroup identification

Strength of subgroup identification was measured with the same three items used in Experiment 1, α = 0.76.

Superordinate integration

Participants attitude and intention about reunification were measured with the same items used in Experiment 1, α = 0.66.

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Descriptive and demographic analyses

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of the seven scales are presented in Table 2. Gender composition, age, and political orientation did not differ significantly across conditions, χ2 < 1, F (1,69) = 1.72, p = 0.194, F < 1, respectively.

3.2.2 Relative identity centrality

A one-way within-subject ANOVA supported that participants' subgroup identity (M = 5.86, SD = 1.84) was significantly more central than their superordinate identity (M = 4.34, SD = 1.86), F (1, 69) = 47.63, p < 0.001,  = 0.41. Thus, relative identity centrality was computed by subtracting superordinate identity centrality from subgroup identity centrality. Relative centrality ranged from −2.00 to 6.50 (M = 1.52, SD = 1.84).

= 0.41. Thus, relative identity centrality was computed by subtracting superordinate identity centrality from subgroup identity centrality. Relative centrality ranged from −2.00 to 6.50 (M = 1.52, SD = 1.84).

3.2.3 Manipulation check

We submitted the manipulation check to hierarchical regression analyses using superordinate identity uncertainty (0 = certain, 1 = uncertain), relative identity centrality (continuous), and RIP (continuous) as predictors. The main effects of superordinate identity uncertainty manipulation and relative identity centrality were significant, b = −1.93, SEb = 0.44, t(66) = −4.44, p < 0.001; b = −0.33, SEb = 0.12, t(66) = −2.76, p = 0.007, respectively. These main effects were qualified by a two-way interaction of superordinate identity uncertainty and relative identity centrality at a marginally significant level, b = −0.47, SEb = 0.25, t(63) = −1.88, p = 0.065. Consistent to Experiment 1, simple slope analysis revealed that people for whom superordinate identity was not so central to their self-concept reported significantly increased feelings of uncertainty in superordinate identity when they were made to feel uncertain (vs. certain) in their superordinate identity, b = −2.85, SEb = 0.65, t(62) = −4.36, p < 0.001. People for whom superordinate identity was central also reported increased feelings of uncertainty in superordinate identity when they were made to feel uncertain (vs. certain) about their superordinate identity at a marginally significant level, b = −1.06, SEb = 0.63, t(62) = −1.67, p = 0.100, but the effect was not as large as that of people for whom superordinate identity was not so central. All other effects were not significant.

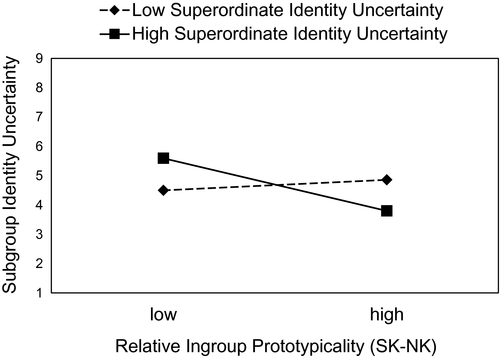

3.2.4 Subgroup identity uncertainty

We submitted subgroup identity uncertainty to the same analysis. The main effect of relative centrality was significant, b = −0.28, SEb = 0.11, t(66) = −2.60, p = 0.011. As predicted, a two-way interaction of superordinate identity uncertainty and RIP was significant, b = −0.56, SEb = 0.20, t(63) = −2.84, p = 0.006 (Figure 3). Consistent with our prediction (H2), when people who perceived South Koreans to be less prototypical of ethnic Korean relative to North Koreans (low ingroup projection) were made to feel uncertain (vs. certain) about superordinate identity, they reported they also felt uncertain about subgroup identity, b = 1.63, SEb = 0.67, t(62) = 2.42, p = 0.019. In contrast, when people who perceived South Koreans more prototypical of ethic Korean relative North Koreans (high ingroup projection) were made uncertain about superordinate identity, they reported they felt as the same level of (un)certainty about subgroup identity as those made to feel certain about superordinate identity, b = −0.85, SEb = 0.68, t(62) = −1.24, p = 0.218.

Putting it differently, in the high superordinate identity uncertainty condition, people who perceived South Koreans as more prototypical ethnic Koreans relative to North Koreans reported significantly less subgroup identity uncertainty than those who perceived South Koreans as less prototypical ethnic Koreans relative to North Koreans, b = −0.49, SEb = 0.18, t(62) = −2.69, p = 0.009. However, in the low superordinate identity uncertainty condition, RIP was not significantly associated with subgroup identity uncertainty, b = 0.14, SEb = 0.15, t(62) = 0.93, p = 0.356.

No other effects were significant.

3.2.5 Subgroup identification

We submitted subgroup identification to the same analysis. All effects were not significant, ps > 0.13.

3.2.6 Superordinate integration

We submitted integration attitude to the same analysis. The main effects of superordinate identity uncertainty, relative centrality, and relative ingroup protorypicality were significant, b = −0.92, SEb = 0.40, t(66) = −2.32, p = 0.024; b = −0.48, SEb = 0.11, t(66) = −4.42, p < 0.001; b = 0.21, SEb = 0.10, t(66) = 2.06, p < 0.044. A two-way interaction of relative identity centrality and RIP was marginally significant, b = 0.11, SEb = 0.06, t(63) = 1.77, p = 0.081. All other effects were not significant.

3.2.7 Integration intention

We submitted integration intention to the same analysis. The main effect of relative identity centrality was significant, b = −0.20, SEb = 0.07, t(66) = −2.81, p = 0.007, such that people for whom subgroup was more central supported integration less than people for whom subgroup was less central. All other effects were not significant.

3.3 Discussion for Experiment 1 and 2

Experiments 1 and 2 supported our key predictions. Experiment 1 showed that when people were made to feel uncertain about a subgroup identity that was central to their self-concept, they were more certain about their superordinate identity and strengthened superordinate identification regardless of ingroup projection. They also increased their support for integration.

In Experiment 2, we made people feel uncertain about their superordinate identity. When people perceived their subgroup (South Korea) less prototypical of superordinate ethnic Koreans relative to the other subgroup (North Korea) (low ingroup projection), they also felt uncertain about their subgroup identity (H2: uncertainty spillover). However, when people perceived their subgroup to be more prototypical of the superordinate ethnic Korean identity than the other subgroup (high ingroup projection), they did not feel uncertain about their subgroup (H3).

Experiment 1 and 2 support our core argument that recategorization and ingroup projection resolve identity-uncertainty in hierarchical self-categorizations. We also discovered that for subgroups with low ingroup projection, uncertainty at a superordinate level can spill over to a subgroup level and people feel uncertainty in both identities simultaneously. How would people respond to this dual identity-uncertainty?

3.4 Overview for Experiment 3 and 4

When people feel uncertain about their superordinate and subgroup identity simultaneously, neither recategorization nor ingroup projection may be an effective way to reduce uncertainty. Rather, both processes may exacerbate uncertainty via a spillover effect. For recategorization and ingroup projection to reduce identity-uncertainty, at least one identity must be a source of identity certainty for the other identity.

Another effective way to resolve uncertainty is to make a group entitative and clearly defined by making group boundaries clearer, more rigid, and less permeable. The clarity of group boundaries is one group property along with common fate, shared goals, and member similarity that is an important cue to perceptions of entitativity (Campbell, 1958; Castano, Yzerbyt, & Bourguignon, 2003, Study 4; Lickel et al., 2000). However, it is not easy to simultaneously enhance both superordinate and subgroup entitativity. Drawing clear and rigid boundaries between subgroups may increase subgroup entitativity but it can also fragment the superordinate group into factions and thus decrease superordinate group entitativity.

For entitativity enhancement to work people need to choose one group—either the subgroup or the superordinate group, whichever is more important to them. If the subgroup is relatively more central than the superordinate group people might pursue greater subgroup autonomy within and separation from the superordinate group, such that their subgroup is, distinctive from the other subgroups (see Wagoner & Hogg, 2016). In contrast, if the superordinate group is relatively more central than the subgroup people might pursue an integrationist strategy that promotes superordinate integration so that the superordinate group can be one cohesive entity without internal factions.1

Experiments 3 and 4 orthogonally manipulated uncertainty at both superordinate and subgroup levels in the context of Korea and Scotland, respectively, and tested if people would enhance the entitiativity of the the group that is more central to their self-concept (H4). We tested our hypothesis in two contexts: North–South Korea relations over potential reunification, and United Kingdom–Scotland relations over potential Scottish independence. In both contexts, people have hierarchical self-categorizations—South Korean identity nested within ethnic Korean identity, and Scottish identity nested within British identity.

4 EXPERIMENT 3

Experiment 3 tested H4 in the Korean peninsula. When people feel uncertain about both superordinate ethnic Korean and subgroup South Korean identity simultaneously, they will reconfigure subgroup structure to make entitative the group more central to their self-concept. Those for whom South Korean identity is more central than ethnic Korean identity will oppose South–North Korean reunification so that South Korea has a clear boundary with North Korea, whereas those for whom ethnic Korean identity is more central than South Korean identity will support South–North Korean reunification so that the ethnic Korean group can be one cohesive entity without internal fragmentation. We orthogonally manipulated superordinate and subgroup identity uncertainty in Experiment 3.

4.1 Method

4.1.1 Participants and design

Ninety-two introductory psychology students in a private university in Seoul, South Korea participated in exchange for course credit. They were randomly assigned to conditions formed by the 2 × 2 manipulation of superordinate identity uncertainty (High vs. Low) and subgroup identity uncertainty (High vs. Low). Ninety-one participants (42 female, 49 male; 18–28 years of age around a mean of 21.08 years) were included in the analysis after removal of a participant with missing data. Given the design of the study, this sample size would yield 87% power to detect a medium-sized effect (f2 = 0.15). In addition to exclusions and power analysis, we report all measures and manipulations below.

4.1.2 Procedure

The procedure is identical to Experiment 1 except that superordinate and subgroup identity uncertainty are orthogonally manipulated (counterbalanced).

Relative identity centrality

How central participants' subgroup identity to their self-concept relative to superordinate identity was measured and constructed in the same manner as Experiments 1 and 2 by subtracting superordinate identity centrality (r = 0.68, p < 0.001) from subgroup identity centrality (r = 0.66, p < 0.001).

Identity uncertainty manipulation

Superordinate and subgroup identity uncertainty were orthogonally manipulated in the same priming method of Experiment 1 and 2. The presenting order was counterbalanced.

Manipulation check

Manipulations of superordinate and subgroup identity uncertainty were checked by the semantic differential scale (−4 uncertain, unclear, unsure, 4 certain, clear, sure); α = 0.94, α = 0.90, respectively.

Superordinate and subgroup identification

Strength of superordinate identification with being ethnic Korean was measured with seven items (Hogg & Hains, 1996) that asked participants how much they felt they belonged to ethnic Korean group, how well they felt they fit into ethnic Korean people, how strongly they felt they identified as ethnic Korean, how strongly they would stand up for ethnic Korean people if they were criticized, how glad they felt to be ethnic Korean, how much they felt that they were attached to ethnic Korean people, and how much they had a feeling of bond with other ethnic Koreans, 1 not at all, 9 very much, α = 0.93. Strength of subgroup identification with South Korea was measured in the same manner as superordinate identification, α = 0.93.

Superordinate integration

Participants' general attitudes toward reunification were measured with one item: “How much do you support reunification of North and South Korea?”, 1 not at all, 9 very much. Participants were presented with eight well-known policies relating to reunification of North and South Korea: Engagement policy toward North Korea (aka Sunshine policy), exchange visits of separated families, common fisheries policy, Gaesung industrial complex, Kumgangsan tour project, Inter-Korea rail link, cultural exchange, and development of unified, unabridged Korean language dictionary. Participants indicated their support for each policy, 1 not at all, 9 very much, α = 0.88.

4.2 Results

4.2.1 Descriptive and demographic analyses

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of the seven scales are presented in Table 3.Gender composition, age, and political orientation did not differ significantly across conditions;  (1) = 0.04, p = 0.845; Fs < 1.

(1) = 0.04, p = 0.845; Fs < 1.

4.2.2 Presentation order

We submitted the main dependent variables (superordinate identification, subgroup identification, integration attitude, and intention) to hierarchical regression analyses using superordinate identity uncertainty (0 = certain, 1 = uncertain), subgroup identity uncertainty (0 = certain, 1 = uncertain), relative identity centrality (continuous), and presentation order (0 = superordinate uncertainty manipulated first, 1 = subgroup uncertainty manipulated first) as predictors. No main or high-order effects of presentation order on superordinate identification, subgroup identification, integration intention were found, ps > 0.14. Even though there was a marginal significant three-way interaction of superordinate identity uncertainty, relative centrality, and presentation order on integration attitude, b = −1.00, SEb = 0.53, t(76) = −1.89, p = 0.063, simple slope analyses revealed the simple effects of presentation order were not significant, ps > 0.24.

4.2.3 Relative identity centrality

A two-way within-subject ANOVA supported that participants' subgroup identity (M = 6.08, SD = 1.73) was significantly more central than their superordinate identity (M = 4.74, SD = 1.81), F (1, 90) = 48.21, p < 0.001,  = 0.35. Thus, we constructed relative identity centrality by subtracting superordinate identity centrality from subgroup identity centrality. Relative identity centrality is ranged from −2.00 to 7.50 (M = 1.35, SD = 1.85).

= 0.35. Thus, we constructed relative identity centrality by subtracting superordinate identity centrality from subgroup identity centrality. Relative identity centrality is ranged from −2.00 to 7.50 (M = 1.35, SD = 1.85).

4.2.4 Manipulation check

Superordinate identity uncertainty

We submitted the superordinate identity uncertainty manipulation check measure to hierarchical regression analyses using superordinate identity uncertainty (0 = certain, 1 = uncertain), subgroup identity uncertainty (0 = certain, 1 = uncertain), relative identity centrality (continuous) as predictors. The main effects of superordinate identity uncertainty manipulation and relative centrality were significant, b = −2.04, SEb = 0.39, t(87) = −5.27, p < 0.001; b = −0.26, SEb = 0.10, t(87) = −2.50, p = 0.014. Participants in the high superordinate identity uncertainty condition reported significantly higher levels of superordinate identity uncertainty (M = −0.80, SD = 1.81) than those in the low condition (M = 1.10, SD = 1.95), F (1, 87) = 24.07, p < 0.001. Neither a main effect of subgroup identity uncertainy nor a two-way interaction was significant, ps > 0.14. The orthogonal manipulation worked successfully.

Subgroup identity uncertainty

We also submitted the subgroup identity uncertainty manipulation check measure to the same analysis. The main effects of subgroup identity uncertainty manipulation and relative centrality were significant, b = −1.40, SEb = 0.35, t(87) = −4.02, p < 0.001, b = 0.25, SEb = 0.10, t(87) = 2.66, p = 0.009. Participants in the high subgroup identity uncertainty condition reported significantly higher levels of subgroup identity uncertainty (M = 0.60, SD = 1.74) than those in the low condition (M = 1.87, SD = 1.63), F (1, 87) = 12.66, p < 0.001. Neither a main effect of superordinate identity uncertainty nor a two-way interaction was significant, ps > 0.29. The orthogonal manipulation worked successfully.

4.2.5 Superordinate identification

We submitted the superordinate identification to the same hierarchical regression analyses. The main effect of superordinate identity uncertainty was significant, b = −0.75, SEb = 0.31, t(87) = −2.46, p = 0.016; superordinate identity uncertainty significantly weakened superordinate identification. The main effect of relative centrality was significant, b = −0.26, SEb = 0.08, t(87) = −3.18, p = 0.002; the more central participants' subgroup identity, the less strongly they identified with the superordinate group. No other main effects or higher order interactions emerged, ps > 0.10.

4.2.6 Subgroup identification

We submitted the subgroup identification to the same analysis. The main effect of relative centrality was significant, b = 0.26, SEb = 0.08, t(87) = 3.31, p = 0.001; the more central participants' subgroup identity, the more strongly they identified with the subgroup group. No other main effects or higher order interactions emerged, ps > 0.11.

4.2.7 Superordinate integration

We submitted integration attitude to the same analysis. A predicted three-way interaction was not significant, b = −0.20, SEb = 0.49, t(83) = −0.40, p = 0.689. A two-way interactions of relative centrality and superordinate identity uncertainty was significant, b = −0.60, SEb = 0.24, t(84) = −2.54, p = 0.013, and a two-way interaction of relative centrality and subgroup identity uncertainty was also significant, b = −0.52, SEb = 0.24, t(84) = −2.14, p = 0.036.

Even though a three-way interaction was not statistically significant, we conducted simple slope analyses to test our a priori hypothesis (H4). Results revealed that when both superordinate and subgroup identities were certain, relative centrality was positively correlated to integration attitude, b = 0.69, SEb = 0.32, t(83) = 2.17, p = 0.033; people for whom subgroup is central were more likely to support reunification and people for whom subgroup is not so central were less likely to support reunification in general. In contrast, as predicted, when both superordinate and subgroup identities were uncertain, relative centrality was negatively correlated to integration attitude at a marginally significant level, b = −0.38, SEb = 0.22, t(83) = −1.70, p = 0.093, such that people for whom subgroup was central were less supportive of integration and people for whom superordinate was central were more supportive of integration.

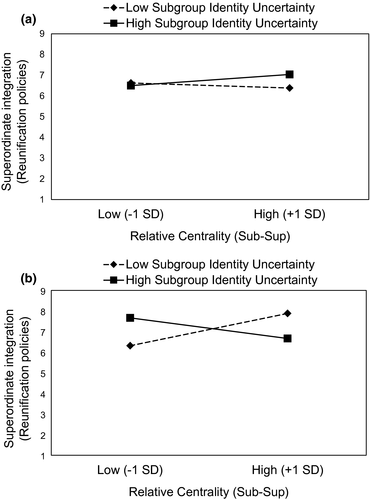

4.2.8 Integration intention

We submitted integration intention to the same analysis. A two-way interaction of relative identity centrality and subgroup identity uncertainty was marginally significant, b = −0.31, SEb = 0.16, t(82) = −1.97, p = 0.052, and was qualified by a predicted significant three-way interaction, b = −0.90, SEb = 0.30, t(83) = −2.98, p = 0.004 (Figure 4).

Following simple slope analysis procedures recommended by Cohen, Cohen, West, and Aiken (2003) and Dawson and Richter (2006), we further examined this three-way interaction by assessing a two-way interaction of relative centrality and subgroup identity uncertainty at high and low levels of superordinate identity uncertainty. A simple two-way interaction of relative centrality and subgroup identity uncertainty was significant at the high superordinate identity uncertainty, b = −0.69, SEb = 0.20, t(83) = −3.51, p < 0.001; but it was not at the low superordinate identity uncertainty, b = 0.21, SEb = 0.23, t(83) = 0.91, p = 0.366.

A significant two-way interaction involved two different simple effects. As predicted (H3), when both superordinate and subgroup identities were uncertain, relative centrality was negatively correlated to integration intention at a marginally significant level, b = −0.27, SEb = 0.14, t(83) = −1.98, p = 0.051, such that people for whom subgroup was central were less supportive of reunification policies and people for whom superordinate group is central were more supportive of reunification policies. Also, we found that when superordinate identity was uncertain but subgroup identity was certain, relative centrality was positively correlated to integration intention, b = 0.42, SEb = 0.14, t(83) = 2.96, p = 0.004.

No other effects were significant.

5 EXPERIMENT 4

Experiment 4 was designed to test H4 in the context of Scottish independence from the Unite Kingdom. Scottish independence provides a comparative context to the case of Korean reunification (Experiment 3). When Scottish people feel uncertain about both superordinate British and subgroup Scottish identity simultaneously, they will reconstruct subgroup structure to make entitative the group more central to their self-concept. Those for whom Scottish identity is more central than British identity will support Scottish independence so that Scotland has a clear boundary with England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, whereas those for whom British identity is more central than Scottish identity will oppose Scottish independence so that the United Kingdom can be one cohesive entity without internal fragmentation.

5.1 Method

5.1.1 Participants and design

Among 67 Scottish participants(52 female, 15 male; 18−45 years of age around a mean of 21.79 years), 49 introductory psychology students in a university in Scotland participated in exchange for course credit and 18 participants participated online from Facebook groups before Scotland's 2014 independence referendum. They were randomly assigned to conditions formed by the 2 × 2 manipulation of superordinate identity uncertainty (High vs. Low) and subgroup identity uncertainty (High vs. Low). Given the design of the study, this sample size would yield 73% power to detect a medium-sized effect (f2 = 0.15).

5.1.2 Procedure

The procedure is identical to Experiment 3 except that there were six items measuring participants' attitude toward Scotland–United Kingdom relations (independence, devolution, union). Here, we report all measures and manipulations below as well as power analysis.

Relative identity centrality

How central participants' subgroup identity to their self-concept relative to superordinate identity was measured and constructed in the same manner as Experiments 1–3 by subtracting superordinate identity centrality (r = 0.72, p < 0.001) from subgroup identity centrality (r = 0.65, p < 0.001). A two-way within-subject ANOVA supported that participants' subgroup identity (M = 5.62, SD = 2.01) was significantly more central than their superordinate identity (M = 4.26, SD = 1.97), F (1, 66) = 17.05, p < 0.001,  = 0.21. Relative identity centrality is ranged from −4.50 to 8.00 (M = 1.36, SD = 2.69).

= 0.21. Relative identity centrality is ranged from −4.50 to 8.00 (M = 1.36, SD = 2.69).

Identity uncertainty manipulation

Superordinate and subgroup identity uncertainty were manipulated in the same manner as Experiment 3. The presenting order was counterbalanced.

Manipulation check

Manipulations of superordinate and subgroup identity uncertainty were checked by the semantic differential scale (1 uncertain, unclear, unsure, 9 certain, clear, sure); α = 0.94, α = 0.89, respectively.

Superordinate–subgroup relations (independence, devolution, union)

Participants' attitudes toward Scotland–United Kingdom relations was measured with six items (Sindic & Reicher, 2009) which include two independence items (“Scotland should become an independent country, separate from the rest of the UK,” “The goal of having a parliament in Scotland should be ultimately to achieve total independence in the long-term”; r = 0.84, p < 0.001), two devolution items (“Scotland should have its own parliament but remain part of the UK,” “I support devolution but I don't support independence nor do I support being in the UK without a Scottish parliament”; r = 0.73, p < 0.001) and two union items (“Scotland should remain part of the UK but without a separate parliament,” “I support the Union in Britain but not devolution or independence”; r = 0.61, p < 0.001), 1 strongly disagree, 9 strongly agree.

5.2 Results

5.2.1 Descriptive and demographic analyses

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of the six scales are presented in Table 4. Gender composition, age, and political orientation did not differ significantly between conditions;  (1) = 0.47, p = 0.495 (Fisher exact test p = 0.566); ps > 11.

(1) = 0.47, p = 0.495 (Fisher exact test p = 0.566); ps > 11.

5.2.2 Manipulation Check

Superordinate identity uncertainty

We submitted the superordinate identity uncertainty manipulation check measure to hierarchical regression analyses using superordinate identity uncertainty (0 = certain, 1 = uncertain), subgroup identity uncertainty (0 = certain, 1 = uncertain), and relative identity centrality (continuous) as predictors.

The main effect of superordinate identity uncertainty was not significant, b = −0.26, SEb = 0.42, t(63) = −0.62, p = 0.540. However, a two-way interaction of superordinate identity uncertainty and relative centrality was marginally significant, b = 0.31, SEb = 0.16, t(60) = 1.99, p = 0.051. Simple slope analyses indicated that the simple main effect of superordinate identity uncertainty at high relative centrality was significant, b = 3.02, SEb = 1.31, t(60) = 2.30, p = 0.025; but it was not at low relative centrality, b = 1.34, SEb = 1.42, t(60) = 0.95, p = 0.347. Viewed differently, the simple slopes of relative centrality at high and low superordinate uncertainty conditions were not significant, ps > 0.28.

We also found a two-way interaction of superordinate uncertainty and subgroup uncertainty conditions was marginally significant, b = −1.60, SEb = 0.82, t(60) = −1.94, p = 0.057. The simple main effect of superordiante uncertainty condition at high level of subgroup uncertainty condition was significant, b = −1.43, SEb = 0.59, t(60) = −2.45, p = 0.017; but it was not at low level of subgroup uncertainty condition, b = 0.16, SEb = 0.63, t(60) = 0.26, p = 0.797. Viewed differently, the simple main effects of subgroup uncertainty condition at high and low levels of superordinate uncertainty condition were not significant, ps > 0.16. No other main or high-order effects were significant.

Subgroup identity uncertainty

We submitted subgroup identity uncertainty manipulation check measure to the same hierarchical regression analyses. The main effect of relative centrality was significant, b = 0.14, SEb = 0.07, t(63) = 2.01, p = 0.048. The main effect of subgroup uncertainty condition was not significant, b = −0.41, SEb = 0.38, t(63) = −0.12, p = 0.914; neither was superordinate uncertainty condition, b = −0.16, SEb = 0.38, t(63) = −0.42, p = 0.674.

A two-way interaction of subgroup identity uncertainty and relative centrality was significant, b = 0.32, SEb = 0.14, t(60) = 2.29, p = 0.025. The simple slope analyses indicated that the simple main effect of superordinate uncertainty condition at high relative centrality was significant, b = 2.70, SEb = 1.17, t(60) = 2.30, p = 0.025; but it was not at low relative centrality, b = 0.98, SEb = 1.27, t(60) = 0.77, p = 0.446. Viewed differently, the simple slopes of relative centrality at high and low superordinate uncertainty conditions were not significant, ps > 0.18. No other effects were significant.

5.2.3 Superordinate–subgroup relations

Independence

We submitted independence to the same hierarchical regression analyses. Consistent to Experiment 3, a three-way interaction was marginally significant, b = 0.74, SEb = 0.44, t(59) = 1.69, p = 0.096. A simple two-way interaction of relative centrality and subgroup identity uncertainty was not significant at low superordinate identity uncertainty, b = −0.24, SEb = 0.33, t(59) = −0.72, p = 0.472. A simple two-way interaction of relative centrality and subgroup identity uncertainty was marginally significant at high superordinate identity uncertainty, b = 0.51, SEb = 0.29, t(59) = 1.73, p = 0.090. A two-way interaction involved two simple effects. When superordinate identity was uncertain but subgroup identity was certain, relative centrality was not significantly associated with independence, b = −0.12, SEb = 0.24, t(59) = −0.49, p = 0.626. As predicted (H3), when both superordinate and subgroup identities were uncertain, relative centrality was significantly positively associated with independence, b = 0.39, SEb = 0.17, t(59) = 2.30, p = 0.025, such that people for whom subgroup was more central than superordinate group were more supportive of subgroup separation whereas people for whom subgroup is less central than superordinate group were less supportive of subgroup separation.

Devolution

We submitted devolution to the same analysis. The main effect of relative identity centrality was significant, b = −0.19, SEb = 0.08, t(63) = −2.28, p = 0.026. No other main effects or higher order interactions were significant, ps > 0.29. We performed simple slope analysis for an explorative purpose. No simple slope was significant, ps > 0.12.

Union

We submitted union to the same analysis. The main effect of relative identity centrality was significant, b = −0.30, SEb = 0.08, t(63) = −3.76, p < 0.001. No other main effects or higher order interactions were significant, ps > 0.34. We tested a priori H3 by performing simple slope analysis. Consistent to Experiment 3, when both superordinate and subgroup identities were uncertain, relative centrality was significantly negatively correlated to union, b = −0.41, SEb = 0.13, t(59) = −3.16, p = 0.003, such that people for whom subgroup was more central than superordinate group were less supportive of union whereas people for whom subgroup was less central than superordinate group were more supportive of union. All other simple slopes were not significant, ps > 0.11.

5.3 Discussion for Experiment 3 and 4

Experiment 3 and 4 supported our entitativity enhancement hypothesis (H4) that when people simultaneously felt uncertain about superordinate and subgroup identities, they made more entitative the group that was most central to their self-concept. People for whom the subgroup was central increased their support for subgroup separation (i.e., Scottish independence) and decreased their support for superordinate integration (i.e., Korean reunification and Scotland union) so that the subgroup can have a clear, impermeable boundary, distinctive from the other subgroups. In contrast, people for whom their superordinate group was more central decreased their support for subgroup separation and increased their support for superordinate integration so that the superordinate group could become one cohesive entity without internal factions. As a result, under dual uncertainty, group members' opinions on superordinate–subgroup relations became polarized.

6 GENERAL DISCUSSION

Four experiments provided new data on how recategorization and ingroup projection interplay to reduce identity-uncertainty at a superordinate and subgroup level. Recategorization and projection work together to maintain an overall level of identity-certainty in people's hierarchical system of self-categorizations. When people feel uncertain about subgroup identity they recategorize themselves into and feel certain about their superordinate identity (H1, Experiment 1) regardless of whether the subgroup is more or less prototypical of the superordinate group than other subgroups are. When people feel uncertain about their superordinate identity, however, they also become uncertain about their subgroup identity (H2, Experiment 2). However, ingroup projection reduces the uncertainty spillover effect such that people feel less uncertain about their superordinate identity or about their subgroup identity (H3, Experiment 2).

In Experiment 2, we found that for a subgroup with low ingroup projection, the uncertainty spillover effect results in uncertainty at both superordinate and subgroup levels. In this case, recategorization and ingroup projection only exacerbate uncertainty. This situation can be regarded as identity moratorium (Marcia, 2000), where people do not commit to their group anymore but remain in the group as a temporary shelter and explore alternative groups. They may join an alternative group if group boundaries are permeable. But if boundaries are impermeable they may choose the more extreme option of seceding from the superordinate group collectively and creating a new breakaway group if their subgroup is more important (Sani, 2005). If the superordinate group is more important, they may reject subgroup identity and identify solely with the superordinate category. In this way, people chose either superordinate identity or subgroup identity depending on which group is self-conceptually more central and then elevate that group's entitativity (H4, Experiment 3 and 4). Thus, depending on relative identity centrality, subgroup members may disagree about the issue of integration vs. separation.

6.1 Group resilience in uncertain times

The present research suggests how social groups can be resilient in uncertain times. Social groups and identities unavoidably experience uncertainty. As the social environment changes constantly, groups will adapt. For example, individuals and political groups reposition themselves as political landscape changes (Gaffney, et al., 2014). Employees often feel uncertain about their organizational or departmental identities during organizational restructuring (e.g., mergers and acquisitions, turnover) (Van Knippenberg, Van Knippenberg, Monden & de Lima, 2002). Adaptability to change is the key characteristic of resilient groups.

The present research suggests that for groups to be resilient they need to prevent low-status or numerical minority subgroups from identity moratorium. They should encourage low-status or minority subgroups to have equal opportunities to project their attributes onto a superordinate group. In this way, minorities can contribute as much as a high-status or majority subgroup to restoring superordinate identity. For example, an organization can have a leadership coalition group that not only represents different subgroups within the larger collective but also allows each subgroup to have an equal voice regardless of size (e.g., boundary-spanning leadership coalition in Hogg, Van Knippenberg, & Rast, 2012, p. 243; integration-equality merger pattern in Giessner et al., 2006, p. 351). In this way, all subgroups can be recognized and have equal representativeness.

6.2 Reducing intergroup bias

Research on how to reduce bias and conflict between groups suggests that relations improve when subgroups can transcend their differences by recategorizing themselves into a shared superordinate category (e.g., Gaertner, Dovidio, Anastasio, Bachman, & Rust, 1993). However, to be most effective this superordinate identification needs to coexist with sustained subgroup identification so that people, particularly those who identify strongly with their subgroup, do not feel that their cherished subgroup identities are under threat of disappearance (e.g., Hewstone & Brown, 1986; Hogg, 2015; Hornsey & Hogg, 2000). Mummendey and Wenzel (1999) have further suggested that this process is helped if the superordinate group prototype is unclear, complex, or broad. An “undefined” superordinate prototype such as this allows diverse subgroup attributes to be included and considered normative and acceptable.

The present research suggests, however, that an undefined superordinate prototype might have the opposite effect. It might create superordinate identity-uncertainty and lead subgroups into a dynamic of competitive subgroup projection. Members of a more prototypical subgroup would cognitively redefine the vague prototype through ingroup projection, while members of a less prototypical subgroup would experience uncertainty at both superordinate and subgroup levels due to superordinate-to-subgroup depersonalization, which might lead to the emergence of disagreeing factions within the subgroup.

Social psychologists and policy makers might find it helpful to design the representation of a superordinate category in such a way that it can include diverse subgroups yet reduce identity-uncertainty. Although identity-uncertainty was not examined, two previous studies (Peker et al, 2010; Waldzus et al., 2003) found that ingroup projection is reduced when people represent a superordinate category with many different prototypes yet have a clear sense of a subgroup structure.

6.3 Limitations and future directions

In the present research, we focused mainly on the effect of chronic ingroup projection. Although it is an important research question, there is a possibility that ingroup projection can be initiated by identity uncertainty. For example, when people feel uncertain about their superordinate identity, subgroups regardless of their status or numerical size may engage in ingroup projection because own-subgroup attributes are more available and accessible than those of other subgroups. A correlational study by Jung et al. (2016) suggests that this is indeed the case. They found that the more superordinate and subgroup attributes overlap, the more strongly subgroup identity uncertainty impedes superordinate identification. This happens because a highly prototypical subgroup may project subgroup uncertainty onto a superordinate group and thus feel uncertain about their superordinate identity and weaken superordinate identification. Although this correlational study is useful to confirm that the phenomenon of interest really exists, future research might benefit from an experimental methodology that tests whether situational ingroup projection would be triggered by superordinate uncertainty.

Relative identity centrality has a significant main and a marginally significant interaction effect on the items that check the uncertainty manipulation although the uncertainty manipulation (βs = −0.26; −0.45) had a larger effect on the manipulation check variable than relative identity centrality (βs = 0.23;−0.26). People may have a chronically clear sense of the group identity that is important in defining who they are as the previous correlational studies have shown (Jung et al., 2018; Wagoner, Belavadi, & Jung, 2017). For a two-way interaction (i.e., people reported less feeling of uncertainty when they were made uncertain about the group that was central vs. peripheral to their self-concept), future research needs to be done to invetigate whether this may be a defensive response to restore their feelings of certainty.

6.4 Conclusion

Recategorization and ingroup projection interplay to construct a clear, certain sense of identity in our hierarchical self-categorizations. In uncertain times, these two identity-uncertainty reduction processes are a formula for group resilience.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are immensely grateful to Dr. Gary J. Lewis at Royal Holloway, University of London for sharing his insights and resources that greatly assisted the research. We would like to express our very great appreciation to the following research assistants at Sungkyunkwan University, Ha-Yeon Lee, Jae-Hoon Choi, Jung-Gil Seo, and Soohyun Lee for their assistance with data collection.

| Variable (items) | α | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Relative identity centrality (4 items) | 1.51 | 1.96 | – | |||||

| 2. Subgroup identity uncertainty (0 = certain, 1 = uncertain) | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.00 | – | ||||

| 3. Superordinate identity uncertainty (5 items) | 0.90 | 5.52 | 1.59 | 0.06 | −0.04 | – | ||

| 4. Superordinate identification (3 items) | 0.79 | 5.27 | 1.53 | −0.30** | −0.07 | −0.47*** | – | |

| 5. Superordinate integration | 5.58 | 2.19 | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.26* | 0.21 | – | |

| 6. Integration intention (3 items) | 0.80 | 7.11 | 1.52 | −0.24* | 0.07 | −0.33** | 0.35** | 0.57*** |

- p < 0.10;

- * p < 0.05;

- ** p < 0.01;

- *** p < 0.00.

| Variable (items) | α | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Relative identity centrality (4 items) | 1.52 | 1.84 | – | ||||||

| 2. Relative ingroup prototypicality (6 items) | −0.12 | 1.95 | −0.05 | – | |||||

| 3. Superordinate identity uncertainty (0 = certain, 1 = uncertain) | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.07 | 0.01 | – | ||||

| 4. Subgroup identity uncertainty (5 items) | 0.92 | 4.69 | 1.70 | −0.29* | −0.17 | 0.003 | – | ||

| 5. Subgroup identification (3 items) | 0.76 | 6.59 | 1.28 | 0.17 | 0.17 | −0.04 | −0.25* | – | |

| 6. Superordinate integration | 5.89 | 1.97 | −0.47*** | 0.23 | −0.26* | 0.07 | −0.01 | – | |

| 7. Integration intention (3 items) | 0.66 | 7.49 | 1.16 | −0.33** | 0.04 | −0.19 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.57*** |

- † p < 0.10;

- * p < 0.05;

- ** p < 0.01;

- *** p < 0.00.

| Variable (items) | α | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Relative identity centrality (4 items) | 1.35 | 1.85 | – | ||||||

| 2. Superordinate identity uncertainty (0 = certain, 1 = uncertain) | 0.56 | 0.50 | −0.09 | – | |||||

| 3. Subgroup identity uncertainty (0 = certain, 1 = uncertain) | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.13 | −0.12 | – | ||||

| 4. Superordinate identification (7 items) | 0.93 | 5.45 | 1.53 | −0.28** | −0.23* | 0.10 | – | ||

| 5. Subgroup identification (7 items) | 0.93 | 6.47 | 1.43 | 0.34*** | −0.08 | 0.07 | 0.43*** | – | |

| 6. Superordinate integration | 6.16 | 2.06 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.32** | 0.23* | – | |

| 7. Integration intention (8 items) | 0.88 | 6.88 | 1.29 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.39*** | 0.34*** | 0.59*** |