Get together, feel together, act together: International personal contact increases identification with humanity and global collective action

Abstract

Declining natural resources or climate change are examples of global challenges that characterize our globalized world. A sustainable human cohabitation depends on global intergroup cooperation and joint efforts to solve these crises. Intergroup contact tends to reduce intergroup prejudice and can facilitate such intergroup cooperation. Another line of research indicates that these improved attitudes may reduce the motivation to collective action among members of disadvantaged groups in situations of intergroup conflict, indicating that intergroup contact and collective action are antagonistic processes. In this article, we argue instead that intergroup contact may facilitate collective action intentions against global crises (e.g., climate change or global economic inequalities) that require international cooperation. Specifically, we propose international contact to foster recategorization on the level of all humanity, and in turn intentions of globally responsible actions. We first review evidence of the effects of contact with regard to intergroup cooperation. It is followed by a discussion of the unique nature of collective action concerning a common global challenge. We then integrate both lines of research within the Common Ingroup Identity approach. In two empirical studies (N1 = 104, N2 = 259), we show first evidence that international contact increases identification and solidarity with humanity which then (according to Study 2) is also positively related to intentions of global responsible behavior. Our analysis thus suggests that intergroup contact, beyond the improvement of attitudes, may serve as an effective initiator of social change.

1 INTRODUCTION

Against the background of a globalized world that is characterized by global crises such as near-to-finite natural resources or climate change, global harmony not only depends on positive intergroup attitudes, but more importantly also requires global cooperation and global collective action to solve these problems. Since Allport (1954) first introduced the idea that intergroup contact improves attitudes toward people from other groups, many researchers found support for this effect across very different contexts and populations (for a meta-analysis, see Pettigrew & Tropp, 2008). Additionally, Sally (2001) found that contact facilitated subsequent cooperation. More recent publications, however, have pointed to the negative side effects of intergroup contact (e.g., Wright & Lubensky, 2009). For example, due to improved intergroup attitudes, contact reduced intentions of collective action against discrimination and intergroup inequalities among members of disadvantaged groups (e.g., Tausch, Saguy, & Bryson, 2015).

We depart from the notion that collective action is not necessarily a response to relative deprivation and intergroup conflict. Instead, we argue that it can also originate from shared demands, such as large-scale environmental crises (Fritsche, Barth, Jugert, Masson & Reese, 2017). For instance, global climate change poses a collective challenge that does not only make intentions of collective action a likely but also an indispensable response. This is inherent to climate change, which is indeed the result of many people’s collective behavior and which can only be tackled by larger collectives (Fritsche et al., 2017; see also Bamberg, Rees & Seebauer, 2015).

Hence, the effects of contact for improving intergroup attitudes and cooperation are not antagonistic to collective action in general. Although it may hinder the collective action of disadvantaged groups in intergroup conflict (cf. Subašić, Reynolds & Turner, 2008; Wright, 2009), intergroup contact may pave the way for joint efforts to solve global problems across group boundaries. We therefore propose a novel approach as to how intergroup contact may foster collective action on the level of higher order social categories. Specifically, we claim this to work through recategorization into one common superordinate in-group (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000), the in-group of all humanity (cf. McFarland, 2010; Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher & Wetherell, 1987). People who identify with a global in-group, should perceive global problems to be problems of their own. They should feel that the responsibility of the global community to solve global crises is also their own responsibility. Indeed, people may not only perceive environmental issues to be a global problem but see also economic inequality and social injustice as such. Thereby, contact-induced identification with all humanity could even contribute to advantaged group members’ inclination to reduce intergroup inequalities and injustices (Gaertner et al., 2016; Reese, 2016; Subašić et al., 2008). Summed-up, we propose to extend the contact hypothesis from intergroup attitudes to global responsible action with superordinate identification on the level of all humanity as the critical mediator. In doing so, we partially solve the apparent antagonism between intergroup attitude improvement through contact and collective action motivation.

2 INTERNATIONAL CONTACT

The cultural dimension of globalization (e.g., transnational communication through social networks, exchange programs; Dreher & Gaston, 2008) and the increasing global connectivity that goes along with it has a strong potential for contact interventions. Previous research on the contact hypothesis consistently shows that positive contact between members of different groups leads to a reduction of prejudice (for a meta-analysis see Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). Affective processes such as greater empathy and less fear toward out-groups mediate this effect (Pettigrew, Tropp, Wagner & Christ, 2011). Meta-analyses (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006; Pettigrew, Tropp, Wagner & Christ, 2011) confirm that the positive effects of intergroup contact interventions occur, regardless of whether the intergroup distinction concerned age, nationality, sex, or other fields of application. Prejudice-reducing effects proved to be stronger under favorable contact conditions, referred to as “optimal conditions” (Allport, 1954: cooperation; equal status within the situation; common goals and the support of contact by the authorities, law, or custom). Nevertheless, these factors are not prerequisites of positive contact outcomes (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006).

Over the past decade, intergroup contact theory has been greatly developed and expanded. Two growing branches of research are particularly relevant for the present work. First, the imagined contact hypothesis posits that the sheer imagination of having positive contact with an out-group member has positive effects in terms of reducing prejudices (for a meta-analysis see Miles & Crisp, 2014). This form of indirect contact has the advantage of being available at any time and with limited resources. Therefore, it may be a low-threshold alternative to direct contact in the case of high barriers (e.g., geographical distance). However, a more recent series of replications showed the original imagined contact effect to be only slightly different from zero (Klein et al., 2014). Still, elaborated forms of imagined contact (e.g., including more detailed information about the interaction context) resulted in an average meta-analytical effect size that was more than twice as strong compared to the original version (Miles & Crisp, 2014), suggesting a promising path for further research and replication.

Second, computer-mediated contact, as a form of direct, but not face-to-face contact holds several advantages, both structurally and psychologically. Access to the Internet has grown tremendously all over the world, opening up an easy, cheap and more ecological contact alternative compared to CO2-intensive travel options. In addition, computer-mediated contact facilitates self-disclosure and reduces anxiety due to its relative anonymity and a well-known and comfortable contact environment (i.e., one’s own home) (Amichai-Hamburger & McKenna, 2006, but see Ruppel et al., 2017). Furthermore, status differences and differences in accents become less evident in text-based communication (Amichai-Hamburger & McKenna, 2006). In the present research, we draw on the advantages of both imagined contact and computer-mediated interaction. We will present a research design based on the contact format of an online chat (Study 1), where the participants imagine engaging in a simulated online interaction.

Compared to the long tradition of work on intergroup contact and attitude change, there is very little research identifying the link between intergroup contact and pro-social behavior between groups. People with contact to victims of severe diseases or accidents showed a greater willingness to help unknown people with the same problem (Small & Simonsohn, 2008). It still remains unclear however as to whether these were instances of out-group or in-group helping. In various economic games, Sally (2001) demonstrated that cooperation between players was higher after direct and indirect contact. McKeown and Taylor (2018) found intergroup contact to mediate the effect of positive peer norms on pro-social behavior toward outgroup members in school children in Nothern Ireland. Wright and Richard (2010) showed that after the formation of intergroup friendships with members of foreign minorities, American students objected more strongly to budget cuts that would have hit the respective minority. These findings provide initial evidence that the effects of intergroup contact might indeed extend beyond improved attitudes. We claim that contact might even foster concrete helping behavior on behalf of other groups. Thus, it may be an important contribution to intergroup harmony and cooperation.

2.1 Processes underlying intergroup contact effects

The processes proposed to account for contact effects are numerous and include both affective (see above) and cognitive approaches such as decategorization (Brewer & Miller, 1984), mutual distinctiveness (Brown & Hewstone, 2005), inclusion of the out-group in the self (Wright, Aron & Tropp, 2001), and recategorization (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000). The decategorization approach (Brewer & Miller, 1984) suggests a personalized contact strategy without salience of group memberships. Instead, it focuses on personal information about the specific contact partner, which should reduce the meaningfulness of the social categories. The mutual group distinctiveness approach suggests that group memberships (categorization) have to be salient at some time during contact. This enables the positive attitudes toward the contact partner to be generalized to the whole out-group (Brown & Hewstone, 2005). The idea of inclusion of the out-group in the self (Wright et al., 2001) suggests that in cross-group friendships, feelings of connectedness to the out-group (the in-group of the contact partner) are established. The out-group thus becomes a part of the person’s self. Hence, the well-being of that group becomes self-relevant and is associated with less bias (see also Turner, Hewstone, Voci & Vonofakou, 2008 for observed intergroup friendships).

The recategorization approach (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000) known as the Common Ingroup Identity Model (Dovidio, Gaertner, & Saguy, 2009) elaborates on the process of recategorizing the self on the level of a larger superordinate group that comprises both the in-group and the out-group. According to the model, shared goals and a supportive environment (the aforementioned “optimal conditions,” Allport, 1954), facilitate the development of shared identity representations. While members of two groups work together cooperatively, the authors propose a shift in the perception of the groups from “us versus them” to an inclusive “we.” Inclusive recategorization should then lead people to apply the rule of favorable treatment of in-group members to former out-group members (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000).

Intergroup contact seems promising to facilitate social change in terms of intergroup harmony, cooperation, and helping. To our knowledge however, there is still no published literature to date on its possible effects on global cooperation.

2.2 Contact and collective action

Models of collective action stand in the immediate tradition of social change research. They aim at predicting people’s intentions to engage in activities, acting in the name of a group to improve the group’s conditions, or to redress their group’s disadvantage (Wright, Taylor, & Moghaddam, 1990). The Social Identity Model of Collective Action (SIMCA; van Zomeren, Postmes & Spears, 2008) as well as the Encapsulation Model of Social Identity in Collective Action (EMSICA; Thomas, Mavor & McGarty, 2011) predict collective activist intentions against an advantaged out-group through people's identification with the in-group, the perceived injustice toward the in-group, and their perceived collective efficacy.

Intergroup contact and friendships can undermine such collective action intentions (Wright & Baray, 2012). Recent findings show that it is in fact negative contact that can encourage collective action (Hayward, Tropp, Hornsey & Barlow, 2018). More positive attitudes toward an advantaged group, related to positive intergroup contact, go along with weaker feelings of anger in response to injustice. This may hinder collective action intentions among disadvantaged group members (Tausch et al., 2015; Wright & Lubensky, 2009). Additionally, contact strategies often aim at reducing the importance of in-group identification, thereby weakening another key predictor of collective action.

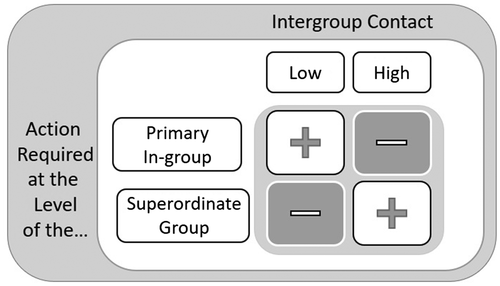

The research cited above focuses on the adverse effects of intergroup contact on collective action under very specific conditions. First, it refers to collective action on the level of the primary in-group. Second, the intergroup context is one of perceived conflict (i.e., relative deprivation) and negative interdependence. However, contact may have quite different effects on collective action when conditions are different.

Figure 1 illustrates that intergroup contact should have different effects on collective action depending on whether collective action is required on the level of the primary in-group or the level of a superordinate group. The former might be the case when the goal is to reduce perceived relative in-group deprivation. The latter may occur when action is required to address concerns that are shared between groups. Specifically, intergroup contact should foster collective action on the level of a superordinate group (e.g., humanity) when the groups share a common fate or challenge that is relevant, and potentially solvable, on the superordinate level of identity only (e.g., global problems that affect and can only be tackled by the whole of humanity).

This is in line with the recently explicated Social Identity Model of Pro-Environmental Action (SIMPEA; Fritsche et al., 2017). It proposes that appraisals of large-scale environmental crises as a collective demand (e.g., climate change) can lead to collective action. Specifically, these appraisals should instigate collective action goals and norms. In turn, those people who highly identify with the group and believe in their collective efficacy are expected to act in accordance with these goals and norms (e.g., pro-environmental action). From this perspective, collective action does not primarily refer to public activist behavior. Instead, it may also comprise non-activist and private everyday behaviors that people carry out in the name of common group membership and as an expression of their social identity (e.g., identified vegans leading a vegan lifestyle). Wright (2009) points out other types of collective action that do not involve confronting any out-group, but which have the goal of making other people join the movement. An example would be members of the anti-coal movement who try to convince other people to also commit themselves to the anti-coal movement (see also Bamberg et al., 2015).

Following up this reasoning, we propose that in the context of collective mitigation of global crises, international contact holds great potential for social change and cross-group collective action. The process we focus on is the forging of superordinate identities.

3 THE SUPERORDINATE IDENTITY OF HUMANITY

As described above, the Common Ingroup Identity Model proposes a process of contact induced recategorization. Both the in-group and the out-group unite under a common superordinate group, extending in-group serving behaviors to the former out-groups (Dovidio et al., 2009). To face global crises, this mechanism could bring all parties together to engage in collective action, by enlarging the in-group to the level of all humans. In accordance with this thinking, McFarland, Webb and Brown (2012) proposed the concept of identification with all humanity. Congruent with the propositions of the Common Ingroup Identity Model, the authors showed that identifying with all humans predicts several attitudes that reflect a positive orientation toward all members of this inclusive in-group. The perceived importance of global affairs, the observance of human rights and the general appreciation of life were all positively related to the identification with humanity. For pro-social behavior, McFarland and colleagues (2012) found correlations of identification with all humanity with the readiness to invest national resources to protect human rights and even with the readiness to donate to a charity. Comparable findings also suggest a consistent relationship between the identification with humanity and pro-social (e.g., Reese & Kohlmann, 2015) as well as sustainable actions (e.g., Renger & Reese, 2017; Reysen & Katzarska-Miller, 2013; Rosenmann, Reese & Cameron, 2016).

Many global problems can be described as social dilemmas. People have the choice to act on behalf of a collective (e.g., using environmental friendly, but, potentially less convenient public transport) or on the grounds of personal self-interest (e.g., using a privately owned car) (Milinski, Sommerfeld, Krambeck, Reed & Marotzke, 2008). While acting selfishly is a rational choice for the individual, all members of the collective suffer when too many choose to do so (Dawes, 1980; Messick & Brewer, 1983). It is important to note that the identification with a superordinate group has been shown to be positively related to cooperation in social dilemmas (Buchan, Croson, & Dawes, 2002; DeCremer & van Vugt, 1999; Kramer & Brewer, 1984; Tanis & Postmes, 2005). For the context of global identification, Buchan and colleagues (2011) found that participants of a complex social dilemma game invested more money in a global (rather than a local or national) public good, the more they identified with the world community. Hence, a global identity can support resolving dilemmas of (non-)cooperation by transforming personal to collective action.

4 THE MODEL AND PRELIMINARY RESULTS

Based on the above-mentioned reasoning, we propose that international contact contributes to social change. We argue that international contact helps to create a shared superordinate global identity on the level of all humanity through the process of recategorization as proposed by the Common Ingroup Identity Model. Identifying with humanity in turn should translate into collective, global responsible action (e.g., pro-environmental action).

We report all data exclusions, manipulations and measures in the respective studies. The data, all materials and analyses can be reviewed on the open science framework (https://osf.io/24gdn/).

5 STUDY 1

In Study 1, we sought evidence for our primary assumption that international contact leads to higher identification with humanity. Taking account of the relevance of computer-mediated contact, especially for younger people, we used a novel experimental chat paradigm that simulates contact.

5.1 Methods

5.1.1 Participants and design

One hundred and four university students (to gain a power of .80% with an α error of <0.05 and an assumed medium effect size of η2 = 0.06) completed an online questionnaire. They were recruited at different German student online portals and randomly assigned to a contact or a no contact condition. We excluded four participants, as they did not have German nationality. The remaining 100 participants (72 female, 27 male, one not specified) had a mean age of M = 24.86 (SD = 3.40). They were included in a raffle of three online shopping vouchers (one 30€ voucher and two 10€ vouchers).

5.1.2 Procedure

Participants were welcomed to the survey entitled “Different aspects of the internet.” After having read some basic instructions, we introduced students to a fictitious new learning website for fine arts. Before exploring the new website, we asked them to generate a short user profile, provide information about their hobbies, their age, their subject of study, their gender, and their nationality. As a measure of actual contact, participants were then asked to indicate the number of international contacts they actually had (up to 10) as well as a proximate number of contact situations per year.

In the experiment, participants then communicated in a simulated online chat forum with a South American (i.e., a Paraguayan) female student with similar interests and a similar taste in art (contact condition), or they learned about a piece of art that other people with similar interests judged as esthetic (control condition).

Participants in the contact condition were informed that the chat was not real but simulated for the purpose of testing the website’s attractiveness and functionality. They were asked to imagine the chat situation to be as real as possible (cf. section on imagined contact). In each trial, they could choose one of two messages to send to their “chat partner.” The answers of the chat partner were the same, regardless of choice. The chat partners exchanged 15 messages about their respective universities, common interests, their nationalities, and the cooperation game they were supposed to play together on the website. In the game, participants had to complete one part of a jigsaw puzzle of nine pieces that made up a colorful work of modern art as quickly as possible. The chat partner was supposed to complete the second part of the same puzzle in the same time (simulated by the computer). Finally, both parts were displayed as one piece of artwork and participants received a positive feedback about their joint task performance. The subsequent scripted communication sequence focused on international collaboration. Thus, the course of the chat followed the proposed contact sequences by Pettigrew (1998): decategorizing personal exchange (common interests), followed by making the different categories salient (exchanging information about one’s own nationality) and ending up with a recategorization by unifying both groups again (international composite work).

Control group participants played the same number of rounds but instead of being in a chat, they had to select one of two possible statements that described their attitudes toward the works of art in each round. Participants completed the jigsaw puzzle task on their own and received positive individual feedback. Subsequently, participants filled out several questionnaires, presented in the order described below, and played a short sequence of a popular association game.

Identification with humanity

As a first measure of identification, we used the multicomponent identification scale by Leach et al. (2008), adapted to assess identification with humanity (referred to as the “multicomponent measure of global identity” in the following). Participants indicated their agreement with 14 independent statements about their own identification with the group of humanity, reflecting five subscales (solidarity, centrality, satisfaction, in-group homogeneity, and in-group self-stereotyping), on a seven-point Likert-typed scale (e.g., “I am glad to be a part of all humanity.”; α = 0.91). To test whether the effect would be independent of the measure we added a second measure of common human identity. The Identification with All Humanity (IWAH)-scale (McFarland et al., 2012) consists of nine, five-point Likert-type items covering different aspects of identification (e.g., “we” thinking, helping others, loyalty). For each of these aspects, participants indicated the extent to which this aspect described their relationship to people in their own community, to people from their own nation, and to people from all around the world (e.g., How much do you identify with [that is, feel a part of, feel love toward, have concern for] each of the following? (a) People in my community; (b) Germans, (c) All humans everywhere). As a measure of identification with humanity, the items concerning all humans everywhere were used only (α = 0.83). The questionnaire order was counterbalanced.

Intergroup attitudes and contact properties

To replicate the original contact hypothesis results, we asked participants about their sympathy toward Paraguayans in general. Additionally, we included one item each about the perceived similarity between Paraguayans and Germans, trust toward Paraguayans, the willingness to engage in contact with Paraguayans, as well as participants’ perceived knowledge about Paraguay (e.g., “What would you say how trustworthy Paraguayans in general are?”), on five-point Likert-typed scales. Participants were then asked if they have been to Paraguay and if they had contact with Paraguans.

Seven items captured perceptions (sympathy, trust, similarity, disclosure, prototypicality of the chat partner for her home country and for the world community) and motivations (wish to have further contact) toward the simulated chat partner (e.g. “What would you say how trustworthy Maria is?”; “Would you like to have chat contact with Maria again?”), in order to get a descriptive idea of the quality of the chat paradigm, all on five-point Likert-typed scales. In the control condition, the participants were presented with the profile of Maria from Paraguay and were asked to answer the same questions regarding this unknown person.

Exploratory items

For exploratory purposes, we included one question regarding the perceived similarity of the goals Germans and Paraguayans have, three questions about the participants’ perception of the presented website and their attitudes to the medium Internet. As there is an ongoing debate about gender-sensitive language in Germany, we also added three questions about the participants’ perception of the language used within the questionnaire. The analyses of those items can be reviewed on the open science framework (https://osf.io/24gdn/).

At the end, participants were thanked and fully debriefed.

5.2 Results and discussion

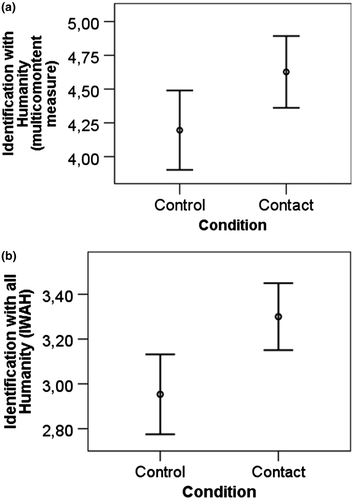

In support of our first hypothesis, participants who imagined engaging in a simulated chat contact with a Paraguayan, compared to the control group, led to higher identification scores on the multicomponent measure of global identity, F(1, 98) = 4.78, p = 0.031; ηp2 = 0.05, and IWAH, F(1, 98) = 8.96, p = 0.003, ηp2 = 0.08, (see also Figure 2 a and b; for means, standard deviations and correlations see Table 1). Additionally, after contact we found a higher general sympathy toward Paraguayans, F(1, 97) = 7.35, p = 0.008, ηp2 = 0.07, higher trust, F(1, 97) = 4.72, p = 0.032, ηp2 = 0.05, higher similarity between Germans and Paraguayans, F(1, 97) = 6.78, p = 0.011, ηp2 = 0.07, and descriptively higher willingness for further contact, F(1, 97) = 2.99, p = 0.087, ηp2 = 0.03, compared to participants to experienced no contact replicating previous findings of the contact hypothesis literature.

| Variables | M overall | SD overall | M contact | SD contact | M control | SD control | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Identification with humanity | 4.41 | 1.01 | 4.63 | 0.94 | 4.20 | 1.03 | – | 0.65* | 0.41* | 0.37* | 0.32* | 0.39* | 0.17 |

| 2. IWAH | 3.13 | 0.60 | 3.30 | 0.53 | 2.95 | 0.63 | 0.65* | – | 0.53* | 0.30* | 0.42* | 0.43* | 0.26* |

| 3. Sympathy Paraguayans | 3.54 | 0.59 | 3.69 | 0.55 | 3.38 | 0.60 | 0.41* | 0.53* | – | 0.22* | 0.50* | 0.40* | 0.14 |

| 4. Similarity Germans—Paraguayans | 2.98 | 0.71 | 3.16 | 0.66 | 2.80 | 0.73 | 0.37* | 0.30* | 0.22* | – | 0.32* | 0.19 | 0.03 |

| 5. Trust toward Paraguayans | 3.49 | 0.54 | 3.61 | 0.53 | 3.38 | 0.53 | 0.32* | 0.42* | 0.50* | 0.32* | – | 0.29* | 0.02 |

| 6. Willingness to have contact | 3.25 | 1.01 | 3.43 | 0.96 | 3.08 | 1.05 | 0.39* | 0.43* | 0.40* | 0.19 | 0.29* | – | 0.17 |

| 7. Actual international contacts | 1.84 | 1.88 | 1.90 | 1.82 | 1.78 | 1.95 | 0.17 | 0.26* | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.17 | – |

- * p < 0.05.

5.2.1 Contact properties

The optimal conditions for contact were achieved: participants in the contact condition rated cooperation (M = 4.00; SD = 0.68), common aims (M = 3.51, SD = 0.74), equal status (M = 4.39, SD = 0.73), and support of authorities (M = 3.69, SD = 0.62; in the whole sample M = 3.55, SD = 0.66 ) all above the scale’s midpoint of “3,” all t(48) ≥ 4.83, all p < 001. They perceived the quality of the chat to be overall positive, with sympathy (M = 3.98; SD = 0.69), trust (M = 3.82; SD = 0.60), similarity (M = 3.45; SD = 0.71), and readiness for further contact (M = 3.35; SD = 0.88) all exceeding the midpoint of the scale, all t(48) ≥ 2.76, all p ≤ 0.008). Only disclosure scores were slightly below the mid-point (M = 2.88; SD = 0.97). The prototypically of the chat partner for her home country (M = 3.18; SD = 0.60) and for the world community (M = 3.37; SD = 0.60) were also rated higher than the midpoint of the scale, both t(48) ≥ 2.14, both p ≤ 0.038.

5.2.2 Exploratory analyses

Exploratory analysis revealed that beyond experimentally induced contact with Paraguans, the number of actual contacts predicted identification with all humans on both the IWAH scale, β = 0.26, t = 2.71, p = 0.008, as well as with the multicomponent measure of global identity, β = 0.17, t = 1.73, p = 0.086 (descriptively positive). Less consistent were the effects of contact frequency on the identification measures. After excluding 14 outliers from the analysis (identified using a boxplot), the effect of contact frequency on the IWAH scale was positive and significant, β = 0.29, t = 2.77, p = 0.007, and descriptively positive on the multicomponent measure, β = 0.10, t = 0.87, p = 0.385.

Analyzing the effects of contact on the five subcomponents of the multicomponent measure, significant positive effects were found for solidarity with humanity, F(1, 98) = 6.88, p = 0.010; ηp2 = 0.07, and for centrality, F(1, 98) = 4.08, p = 0.046; ηp2 = 0.04. The effects of satisfaction, self-stereotyping, and in-group homogeneity were all positive, though not significant, all F(1, 98) < 3.37, all ps > 0.070; all ηp2 < 0.03. A similar pattern emerged for the relationship between actual contacts and the subcomponents. Solidarity again was related to contact most strongly, β = 0.22, t = 2.23, p = 0.028, followed by in-group homogeneity, β = 0.22, t = 2.19, p = 0.031. The other three components were positively related to contact on a descriptive level, all β < 0.15, all t < 1.54, all p > 0.126.

Taken together, Study 1 provides initial evidence for the hypothesis that international contact increases participants’ identification with humanity. The positive relation between actual contact and identification with humanity further supports our hypothesis.

6 STUDY 2

Having established the first path of our model, we aimed to test whether identification with humanity would mediate the effect of international contact on globally responsible intentions and attitudes. Furthermore, our objective was to replicate the effect of simulated contact based on real-life international contacts in a longitudinal design.

6.1 Methods

6.1.1 Participants and design

Two hundred fifty-nine freshman students participated at Time 1. We excluded non-German participants (N = 17). The remaining 242 students who entered the analysis had a mean age of M = 20.16 (SD = 2.74; 179 female, 59 male, 4 other). 116 of them answered the questionnaires at both time points. One hundred twenty-six dropped out or could not be assigned to an existing code after Time 1. The first questionnaire was delivered at the freshman orientation day at the university campus of a major German city. The follow-up questionnaire was completed online. The compensation consisted of an 80-g chocolate bar and a raffle of a shopping voucher of 30€.

6.1.2 Procedure

Participants generated a personal code and completed some demographic questions (age, gender, city of birth, field of study) and the main questionnaires in paper-pencil format. They were informed that they would receive a follow-up questionnaire at the beginning of the second semester (after six months) and would receive a full debriefing afterward. For that purpose, participants entered a contact email address. After 6 months, all participants received an email with the study link for the second part. The questionnaire was identical to the one delivered at Time 1, except that the demographic questions were left out. The students were then thanked and fully debriefed.

The questionnaires presented at both time points were presented in the following order.

Identification with humanity

In this study, we used the adapted multicomponent identification scale by Leach et al. (2008; α1 = 0.87; α2 = 0.87) only, to keep the questionnaire short.

Globally responsible attitudes

To measure globally responsible attitudes and intentions, people rated six items about participants’ general attitudes on global responsibility (e.g., “In order to cause no harm in other countries through my own actions, I would limit my standard of living”; α1 = 0.73; α2 = 0.73) on five-point Likert-typed scales (1—I do not agree at all to 5—I absolutely agree). Four additional items measured pro-environmental behavioral intentions (behaviors selected on the ground of “big point” studies that look at key behaviors with the highest environmental impact; Bilharz, 2008; for example, “To reduce global negative consequences, both in the social sphere, as well as for the environment, I want to avoid air travel in the future”; α1 = 0.46; α2 = 0.65). Due to the poor internal consistency, these four items will be analyzed separately in the following analyses. Additionally, people rated seven items regarding refugee policies in Germany (e.g., “The Federal Government should quickly provide more money for a good accommodation of refugees”; α1 = 0.82; α2 = 0.82).

Exploratory items

For exploratory purposes, we included four items measuring perceived social norms (e.g., “Most people in my surrounding behave environmental friendly.”) and four items measuring personal and collective efficacy beliefs (e.g., “If something is really important to me, then I can reach it.”). Additionally, we asked participants about their attitude toward thriftiness and their identification with Germany and the group of students, all on five-point Likert-typed scales (1—I do not agree at all to 5—I absolutely agree). Finally, we assessed participants’ political orientation on a 21-point scale from very left to very conservative. The analysis of those items can be reviewed on osf.io (https://osf.io/24gdn/).

Actual contact

Participants could indicate up to 10 contacts they had within the last 6 months. They were asked to also specify the frequency of each contact (1—very seldom to 5—very often).

6.1.3 Results

We first compared the participants who answered the questionnaires at both time points with those who responded only at Time 1. We analyzed the differences on all variables and scales at Time 1 with independent sample t tests. Two of the total 28 comparisons were significant; another two were marginally significant (for all other tests ps ≥ 0.13). Respondents who participated at both time points reported somewhat more international contacts than respondents who participated only at Time 1, t(221.72) = 1.89, p = 0.060. Additionally they identified themselves somewhat less with Germany, t(239) = 1.95, p = 0.053. They expressed a lower intention to avoid animal products, t(240) = 2.20, p = 0.029, and were less satisfied to be a part of humanity, t(240) = 2.29, p = 0.023.

6.2 Model test

Replicating the findings of Study 1 with longitudinal data, the number of international contacts at Time 1 was positively related to participants’ identification with humanity at Time 2, β = 0.24, t = 2.41, p = 0.009 (for means, standard deviations and correlations see Table 2).

| Variables | M overall | SD overall | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Number of international contacts (Time 1) | 3.55 | 2.84 | – | 0.24* | 0.26* | 0.24* | 0.27* | 0.18 | 0.38* | 0.06 |

| 2. Identification with humanity (Time 2) | 4.13 | 0.93 | 0.24* | – | 0.39* | 0.29* | 0.115 | 0.10 | 0.19* | 0.10 |

| 3. General global responsibility (Time 2) | 4.45 | 0.76 | 0.26* | 0.39* | – | 0.55* | 0.42* | 0.31* | 0.55* | 0.34* |

| 4. Attitudes toward refugees (Time 2) | 3.91 | 0.71 | 0.24* | 0.29* | 0.55* | – | 0.35* | 0.26* | 0.61* | 0.41* |

| 5. Intention to buy fair-trade (Time 2) | 3.64 | 1.01 | 0.27* | 0.12 | 0.43* | 0.35* | – | 0.24* | 0.61* | 0.17 |

| 6. Intention to avoid air travel (Time 2) | 2.85 | 1.24 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.31* | 0.26* | 0.24* | – | 0.33* | 0.30* |

| 7. Intention to avoid animal products (Time 2) | 3.66 | 1.35 | 0.38* | 0.19* | 0.55* | 0.61* | 0.61* | 0.33* | – | 0.26* |

| 8. Intention to reduce home heating (Time 2) | 3.57 | 1.16 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.34* | 0.41* | 0.17 | 0.30* | 0.26* | – |

- * p < 0.05.

The number of international contacts at Time 1 was positively related to general attitudes on global responsibility at Time 2 as well as with attitudes toward refugees at Time 2 (see Table 3). Regressing participants’ scores on each of the four pro-environmental intention items on the number of international contacts, the intention to buy fair-trade products and the avoidance of animal products revealed significant effects (see Table 3). For the intention to avoid air travel as well as the willingness to reduce home heating, we only found very small and non-significant effects.

| Criterion (Time 2) | Number of contacts | Frequency of contacts | Identification with humanity | Solidarity with humanity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Time 1) | (Time 1) | (Time 2) | (Time 2) | |||||||||

| β | t | p | β | t | p | β | t | p | β | t | p | |

| Attitudes on global responsibility | 0.26 | 2.87 | 0.005 | 0.25 | 2.71 | <0.008 | 0.39 | 4.48 | <0.001 | 0.45 | 5.34 | <0.001 |

| Attitudes toward refugees | 0.24 | 2.67 | 0.009 | 0.24 | 2.58 | 0.011 | 0.29 | 3.17 | 0.002 | 0.32 | 3.54 | 0.001 |

| Intention to buy fair-trade | 0.27 | 3.03 | 0.003 | 0.29 | 3.20 | 0.002 | 0.12 | 1.24 | 0.219 | 0.16 | 1.77 | 0.080 |

| Intention to avoid air travel | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.846 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.915 | 0.10 | 1.12 | 0.267 | 0.18 | 1.94 | 0.055 |

| Intention to avoid animal products | 0.38 | 4.42 | <0.001 | 0.39 | 4.46 | <0.001 | 0.19 | 2.08 | 0.040 | 0.26 | 2.81 | 0.006 |

| Intention to reduce home heating | 0.06 | 0.61 | 0.543 | 0.09 | 0.93 | 0.356 | 0.10 | 1.07 | 0.287 | 0.09 | 0.94 | 0.347 |

Regressing the same variables on identification with humanity at Time 2, we again found positive significant relations for general attitudes on global responsibility, attitudes toward refugees and the avoidance of animal products (see Table 3). The intention to buy fair-trade was related descriptively positive to identification with humanity, while avoiding air travel and reducing home heating showed again the smallest effects (see Table 3).

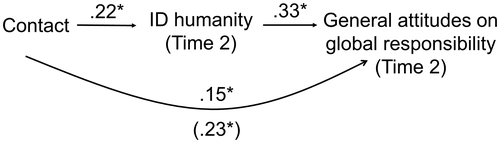

We tested for the proposed indirect effect of number of international contacts (Time 1) on general attitudes on global responsibility (Time 2) via identification with humanity (Time 2). To test for significance of the indirect effect we used bootstrapping procedures (5,000 bootstrapping samples) with the SPSS macro for multiple mediation by Preacher and Hayes (2008) with 95% confidence intervals. We found the mediational pattern that we proposed, B = 0.07, SE(B) = 0.04, 95% CI [0.02, 0.18] (see Figure 3). The same pattern emerged for the dependent variable attitudes toward refugees, B = 0.05, SE(B) = 0.04, 95% CI [>0.00, 0.16]. For the dependent variables of environmental intentions, all indirect effects were positive but with the confidence intervals including zero, Bfair-trade = 0.01, SE(B)fair-trade = 0.03, 95% CIfair-trade [−0.03, 0.07]; Bair travel = 0.02, SE(B)air travel = 0.03, 95% CIair travel [−0.02, 0.09]; Banimal products = 0.02, SE(B)animal products = 0.03, 95% CIanimal products [−0.01, 0.09]; Bhome heating = 0.02, SE(B)home heating = 0.03, 95% CIhome heating [−0.02, 0.10].

6.3 Test for longitudinal effects

As an alternative to explaining these effects in terms of longitudinal effects, these patterns could result from correlations on the cross-sectional level and high stability within the variables over time. To control for such effects in a design with two measurement time points, cross-lagged panel analysis has been used widely in the past. However, the reliability of this method has been questioned recently, especially for variables with great stability over time (Hamaker, Kuiper & Grasman, 2015). Hamaker et al. (2015) have proposed an alternative method to analyze panel data that separates stable between-person differences from the within-person process. Unfortunately, our data only have two waves of measurement and the improved model is only applicable if there are at least three measurement time points. We thus conducted a two-wave, two-variable cross-lagged panel analysis in AMOS 23. As explained above, the results should be regarded with caution.

The model fit was good, χ2(1, N = 116) = 0.54, p = 0.461, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00. The cross-lagged coefficient for international contact on subsequent identification with humanity was small but showed a descriptive trend in the expected direction, β = 0.08, C.R. = 1.23, p = 0.217. The reversed cross-lagged effect of identification with humanity on international contact was nonsignificant and very close to zero, β = 0.03, C.R. = 0.47, p = 0.635. In turn, the stability of contact across both time points was high, β = 0.63, C.R. = 8.80, p < 0.001; as was the stability from Time 1 to Time 2 for identification with humanity, β = 0.66, C.R. = 9.92, p < 0.001. Obviously, although in the expected direction, the cross-lagged regression coefficients were too small to conclusively support our causal findings from Study 1. This might be due to a high stability of contact and identification with humanity across the two time points.

The cross-sectional analyses of both time points are demonstrated in the supplement material.

6.4 Exploratory analysis

In Study 1, we found solidarity to be affected the most by international contact. Here, we aimed at replicating this pattern with longitudinal data and extending the analysis to the measures of global responsibility. We were able to show once again that the solidarity component of identification with humanity (Time 2) profited most from international contact (Time 1; see Table 4). Furthermore, solidarity (Time 2) was found to have consistently positive effects on all measures of global responsibility (Time 2, see Table 3).

| Criterion (Time 2) | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solidarity | 0.32 | 3.64 | <0.001 |

| Centrality | 0.15 | 1.57 | 0.120 |

| Satisfaction | 0.13 | 1.38 | 0.171 |

| In-group homogeneity | 0.12 | 1.25 | 0.214 |

In addition to the number of international contacts, we also assessed the influence of the frequency of contacts. We added the frequencies of all contacts that a person had and weighed the number of contacts with the corresponding frequency. In line with the results using the number of contacts, the frequency of international contacts at Time 1, was positively related to participants’ identification with humanity at Time 2, β = 0.20, t = 2.15, p = 0.033. The pattern of the results from regressing all measures of global responsibility (Time 2) on contact frequency (Time 1) was also the same as for the number of contacts (see Table 3). All effects were significantly positive except for avoiding air travel and reducing home heating.

In Study 2, we replicated the effect of international contact on identification with humanity in a longitudinal data set with real contact. As an extension of the previous results, we found positive indirect effects of international contact (Time 1) on general attitudes to global responsibility (Time 2) and attitudes toward refugees from identification with humanity (Time 2). However, the present study does not allow for a strict test of the causal role of international contact. This is because cross-lagged panel analysis cannot be properly applied as (a) the changes in the variables over time were too small and (b) we only had two measurement points. Future longitudinal studies are warranted that not only include more measurement points but also longer time periods between the measurements that enable sufficient change in contact and global identification to be observed.

7 DISCUSSION

In our endeavor to reconcile the effects of international contact and collective action within the context of global crises, we integrate the well-established Common Ingroup Identity Model (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000) with the rather novel concept of global identity. Our analysis suggests that intergroup contact and collective action for a common good might go hand in hand. In contexts of intergroup conflict and relative deprivation, contact can be an inhibiting factor for collective ingroup action to redress the advantages of a dominant outgroup. However, in a situation of common demands in a global crisis, collective action including all status groups becomes indispensable. Usually, it is not single individual or country who cause a global crisis, such as climate change. Furthermore, they alone do not have the means of mitigating these crises and experienced helplessness (Salomon, Preston, & Tannenbaum, 2017). Instead, global crises are created by and will affect all humanity and might therefore be a shared challenge. The efficacy of large-scale collectives to tackle global crises is usually much higher than personal or subgroup efficacy. Collective crises may thereby motivate action on the level of large-scale collectives rather than on the personal level of identity. Fostering identification with humanity by the means of international contact may thus help to trigger collective action to mitigate global crises.

7.1 Empirical findings

Two studies show initial evidence that international contact does indeed lead to higher identification with humanity (Study 1 and 2), which in turn encourages the intention of globally responsible actions (Study 2). In Study 1, we successfully manipulated international contact in a simulated web-based chat design. We found that people who simulated an in-depth chat with a Paraguayan female student showed higher levels of identification with humanity than those in the control condition. Contact therefore seems to be an innovative approach to foster identification on the highest level of social inclusion.

In Study 2, we replicated this effect with real contacts, in a longitudinal data set with two time points. Both studies thereby contribute substantially to the work on global identity and identification with all humanity (McFarland, 2010; McFarland, Brown & Webb, 2013; McFarland, Webb & Brown, 2012; for an overview, see Rosenmann et al., 2016). In addition, Study 2 showed that international contact (Time 1) mediated through higher global identification (Time 2) was positively related to intentions to act in line with global responsibility (general attitudes on global responsibility, pro-refugee attitudes; both at Time 2). The postulated indirect effects were significantly positive within the longitudinal design. The results on pro-environmental intentions were less distinct. All indirect effects were positive, but the confidence intervals all included zero.

From analyzing changes over time in Study 2, we noticed a very high stability of the number of contacts over a period of 6 months. We assumed that being a newcomer in a major city university would provide a great opportunity to get to know to people from different cultures. On the contrary however, we found a slight decrease in contacts made by newcomers. This demonstrates that having the opportunity to make contact does not necessarily imply actual contact (cf. Dixon & Durrheim, 2003). It would be important to consider means for encouraging international contact in such contexts that are predestined for forming intergroup friendships.

In both studies, international contact most strongly affected the identification subcomponent of solidarity with humanity. In addition, it was found to have strong relationships with measures of global responsibility. Pursuing the analysis of this pattern in further studies could provide more detailed insights into the driving forces behind pro-social behavior in a global setting. It may not be necessary to like the idea of being part of the group of humanity but to sense the responsibility to stand up for it.

7.2 Study designs

We presented data from one experimental (Study 1) and one correlational/longitudinal design (Study 2). For both, there are some limitations. The manipulation of contact in Study 1 is based on imagining the contact situation. Klein and colleagues’ (2014) many-labs study questions the replicability of the original imagined contact effect. With the chat paradigm used in Study 1, we established a very elaborate and realistic form of imagined contact, a simulated computer-mediated contact paradigm. It is characterized by the same advantages as the original task such as high experimental control and flexibility in terms of the contact group. The close-to-reality nature of the design seems to produce more reliable findings, justifying the additional effort of programming such a chat simulation. Although the results presented are encouraging, further research using the same design is needed to determine its reliability. In Study 2 (and cross-sectional in Study 1), we collected data on students’ actual contacts and global identification at two points in time over a 6-month period. Thus, we were able to replicate the effect for real (self-reported) contact experiences. Of course, although we found the expected pattern of actual contacts at Time 1 on global identification as well as global responsible attitudes and intentions at Time 2, this does not provide a strict test of causality. Under conditions of contact and identification being quite stable over 6 months, the longitudinal results may be due to stationary correlations. Thus, Study 2 does not preclude the possibility that the results are due to people who identify more strongly with humanity being more likely to actively seek out more contacts. Even though we cannot rule out this possibility, the results of the experimental setting in Study 1, the descriptive patterns of a cross-lagged panel analysis, as well as previous research on the Common Ingroup Identity Model (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000) support our proposed causal direction from contact to identification. Still, a replication of the findings in manipulated real contact settings would be an important further step to increase confidence in these tentative, preliminary, results.

7.3 Advantages of contact interventions

We believe that the current research has high potential for application. First, contact interventions have the advantage of a possible highly intrinsic appeal to pursue them. Assuming that an actual international contact lifestyle or (online) friendships (for the role of intergroup friendships see Davies, et al., 2011; Pettigrew, 1998) are established, the effect of a contact intervention may be maintained in the long run without any further intervention or investment of effort and money required. At best, the maintaining of international contacts becomes the end in itself.

In addition, adverse reactions to such intervention programs are unlikely, as no demands are placed on the individual. Instead, behavioral change would stem from one’s own intention not to harm one’s friend or his/her group. Furthermore, environmental protective behavior through the motivation to help other people seems to be stable, even under induced mortality salience (Fritsche & Häfner, 2012). This could become even more relevant in the context of (life-threatening) crises.

Another strength that we want to emphasize is the opportunity to nurture international friendships and contact through the Internet, as simulated in Study 1. In Study 2, the intention of avoiding air travel (Time 2) showed a relation close to zero to the number and frequency of international contacts (Time 1). This could be an indication of an actual conflict between pro-environmental intentions and an international orientation. While air travel opens up an easy and comfortable way of indulging in numerous international contacts, at the same time it is one of those behaviors in the private sphere with the most impact on the environment. In future research, it would be interesting to see if there are identifiable factors that lead to the prioritization of either exploring or protecting foreign places following contact. The aim might well be to decarbonize international contact as much as possible.

7.4 Superordinate categories

The category of humanity partly belongs to education (for example when learning about human rights) and partly to the actual political discourse (e.g., the international community as an actor helping in humanitarian crisis) and should be accessible to people if made salient. The question arises as to how or under what conditions humanity becomes salient in contact situations. In interventions referring to the Common Ingroup Identity Model, a superordinate category is typically suggested to participants (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000). We are unaware of systematic research on which superordinate group would be activated if none is explicitly proposed. Our preliminary studies suggest that global identity becomes self-relevant in international contact situations where no other possible superordinate categories were salient. However, in contact situations with highly salient common lower level identities, identification with humanity might be less central (e.g., the membership in international alliances or a shared distinct culture). Instead, people may spontaneously recategorize as members of superordinate groups below the level of humanity. Still, such lower level superordinate groups may also hold empowering functions for collective action. Identifying with the European Union or the Mercosur countries (an association between various South American states) may at least provide a greater collective efficacy than identification on a personal or national level and this could also serve to compensate for feelings of personal helplessness (Fritsche et al., 2017; Salomon et al., 2017).

7.5 Status groups

Lastly, we would like to tie in with the current literature on contact and collective action, where it is imperative to make a distinction between the effects of contact on advantaged versus disadvantaged group members (e.g., Becker, Wright, Lubensky, & Zhou, 2013; Dixon, Levine, Reicher, & Durrheim, 2012; Tausch, Saguy, & Bryson, 2015; Wright & Baray, 2012;). We argue that in a setting of global crisis that would affect all parties, globally responsible collective action tendencies could increase for both advantaged and disadvantaged group members. However, these effects might operate for different reasons. One aspect that might deter especially members of disadvantaged groups from engaging in collective action to mitigate the crisis is distrust. Trust or the expectancy that others will cooperate for the sake of the collective is a strong motivator to engage in cooperative behavior by reducing the fear of being exploited (Foddy & Dawes, 2008; Parks, Henager & Scamahorn, 1996). Exploitation might be particularly aversive and consequential for members of groups low in resources (cf. UNFCCC, 2007). Therefore, a superordinate motivation to collective action of members of disadvantaged groups might profit most from the contact-induced intergroup closeness and increased trust. They could be more inclined to act to mitigate the crisis, if they trust that the advantaged will contribute as well.

Also, a superordinate motivation to collective action might be increased for disadvantaged group members in particular, due to collective efficacy compensating for feelings of helplessness in the face of a global problem (Fritsche et al., 2017; Jugert et al., 2016; Reese & Junge, 2017). In the face of a global crisis, individuals or small collectives do not have a measurable impact on global conditions, even if they personally decided to act in a globally responsible way (e.g., pro-environmental behavior). This state of personal helplessness may reduce people’s intention to act. Recent research has shown that experimentally inducing perceptions of collective efficacy has increased people’s pro-environmental behavior intentions by increasing their sense of environmental self-efficacy (Jugert et al., 2016; Reese & Junge, 2017). Disadvantaged groups usually possess fewer resources to counteract a crisis (Cameron, Shine & Bevins, 2013) and are therefore even more dependent on the cooperation of other groups in order to make a significant difference.

Advantaged groups members' motivation to engage in collective action might primarily benefit from an increased closeness to those threatened most by the crisis. From the perspective of members of industrialized societies, the temporal and geographical gap between one’s own actions and their negative consequences makes it extremely difficult to properly appraise the crisis and adequately respond to it (Barth, Jugert, Wutzler, & Fritsche, 2015; Spence, Poortinga & Pidgeon, 2012). If people perceive large-scale global crises as crises from which they themselves are also affected, then this could resolve ignorance and instigate the willingness to act. This could be true when people mentally include those people in the self who live in affected countries or who will be subject to the future consequences of negative actions taken today (Fritsche et al., 2017; but see Schuldt, Rickard, & Yang, 2018). The intergroup emotions theory proposes that people who identify with a group appraise an occurrence depending on its meaning for that particular group, rather than for the self (Smith & Mackie, 2015). Given a superordinate human identity, the dominant group may take on emotions like fear or anger on behalf of the disadvantaged group that is then part of the in-group, shaping the appraisal of the crisis. This view connects to previous findings on affective processes underlying intergroup contact effects such as empathy, perspective taking, or anxiety about intergroup contact (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2008; Pettigrew, Tropp, Wagner & Christ, 2011).

Furthermore, in the future, it will not only be crucial whether the world continues to “grow together” but also by what norms and goals this emerging common structure is shaped. It may be just as important by what norms and goals this emerging common structure is shaped. Will the global community subscribe to the logic of a shark pond, characterized by fierce competition? Or will it strive toward building the structure of a family where people get what they need to live a fulfilled life? There is still very little research on what exactly people associate with the group of humanity. However, in Western, individualistic cultures, norms and values associated with humanity might be derived from the ideas of humanism and the universal declaration of human rights (Rosenmann et al., 2016). Such humanity-related norms of justice may motivate advantaged groups to analyze their own privileged position and to target global intergroup inequality.

In this vein, it is, for instance, important to examine under which contexts people from different nations meet. Do they encounter each other in collaborative contexts, like international youth camps or electronic self-help forums, or in contexts of international competition, such as hostile international business negotiations or racist chat channels? It may also make a significant difference, whether institutions of global collaboration (or collective action) grow. Is it institutions such as the international court of justice, or common global climate policy agreements that shape the international realm, or policies of national isolationism and egoism, as recently put forward by some prominent national actors (e.g., advocating “America First” or “Brexit” policies)?

8 CONCLUSION

Industrial and cultural globalization has led to tremendous problems with ecological and ethical sustainability on a global scale. However, the effects of international contact carry the promise that, ironically, globalization could also provide the means to overcome global doom. Beyond web-based information bubbles or nationalistic propaganda, worldwide instant communication enables connections to be made with virtually any citizen on the globe. Human propensity to build up interpersonal connections and define the self via larger communities has fueled the development of these structures. If we use them wisely and get to know each other personally, even if we only get to know a few, given the effects of contact on global action intentions, this could still help all.

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.