Exploring the social context of self-leadership—Self-leadership-culture

Abstract

Self-leadership gains in importance in the context of current organizational changes, like in newly developed agile methods, where leadership is mostly replaced by self-leadership (e.g., in Scrum). Until now, the concept of self-leadership has focused on individual- or team-level goal achievement, and is thereby not fully applicable to the broader socio-organizational context. In this paper, we therefore introduce an extended definition of self-leadership, making three major extensions to the existing literature. First, we add an intrapreneurial dimension, which refers to self-leaders directing their actions not just toward their own goals but also toward a larger social entity like the organization as a whole. Second, we define self-leadership as a form of behavior that is in accordance with one’s deeper values, hence authentic. Third, we look beyond the individual or team level, by introducing the idea of a self-leadership-culture (SLC), based on Schein’s concept of organizational culture. In the second part of the paper, we outline the complex relationship of SLC with different contextual variables in leadership, looking at leader–member exchange as well as organizational identification. Furthermore, we propose that SLC generates positive effects such as job satisfaction, work engagement, performance, and innovative behavior. SLC offers a broader perspective for research, compared to self-leadership, but can also be used as an approach for practitioners to enable successful collaboration between self-leaders.

By dealing with men as they are, we make them worse, but by treating them as if they really were what they ought to be, we improve them as far as it is possible. (Von Goethe, 1855, p. 498)

1 INTRODUCTION

Organizations face tremendous and ongoing challenges like rising competitiveness or revolutionary changes in technologies and globalization. Therefore, they need to be flexible and adapt to changing demands in order to remain competitive more than ever before (cf. Baruah & Ward, 2014). Virtually all organizations, independent of size, need to strive for new market opportunities through proactive and innovative behavior (cf. Dess, Lumpkin & McGee, 1999).

As a result of these developments, the traditional leadership role seems to lose its importance, while individual self-leadership is needed more than in the past (cf. Manz & Sims, 2001). Thereby, self-leadership is currently defined as influencing oneself to reach goals effectively, using a variety of different strategies (Neck & Manz, 2010). These strategies imply, for instance, positive self-talk or self-goal setting (Houghton & Neck, 2002), and are helpful in understanding individual or team-level success, like productivity, quality, or career success (for an overview, see Stewart, Courtright, & Manz, 2011). More than that, Manz and Sims (1991) describe leadership toward self-leadership as “the key to tapping the intelligence, the spirit, the creativity, the commitment, and most of all the tremendous unique potential of each individual” (p. 34).

However, this definition is currently limited to the individual and team-level, while it is necessary to find out how self-leadership can be understood and applied in a broader organizational context. We say this, picturing self-leadership as an organization-wide solution to the above-mentioned challenges in economy. With the introduction of SuperLeadership, Manz and Sims (1991) suggested that the best results of self-leadership could be achieved through a totally integrated system, which encourages, supports, and reinforces self-leadership throughout this system. They argued that organizations should try to “foster an integrated world (…) in which self-leadership becomes an exciting, motivating, and accepted way of life” (Manz & Sims, 1991, p. 30). We agree with Manz and Sims regarding the importance to provide a fertile soil for self-leadership in organizations. Additionally, we consider it important to understand social processes around self-leadership in order to get the best results from it. In sum, these developments call for an integrated model that covers self-leadership, as well as the broader socio-organizational context that stretches beyond the behavioral descriptions of single individuals or teams. In the following, we introduce such a holistic model by extending the current self-leadership definition in three predominant ways. We thereby refer to the following three shortcomings that we identified when trying to apply the current definition of self-leadership to the organizational level.

First, self-leadership impedes higher-level success if self-leaders solely focus on their own goals, and march their own beat (see Langfreed, 2000). Employees may, for instance, set themselves the goal to perform better than everyone else in the team, and thereby negatively influence other’s performance and team performance as a whole. We, therefore, seek to extend the current definition by including the concept of intrapreneurship (Pinchot, 1985b). In brief, intrapreneurship implies that employees direct their efforts toward the common good of a broader social entity rather than merely to themselves or their team.

Second, the current definition of self-leadership could imply that individuals may change their behavior but also their values and deeply held assumptions, in order to reach goals. We argue that in order for self-leadership to be truly self-determined, actions and decisions of self-leaders should be based on their inner values. Actions that are in line with one’s deeply held values are represented in authenticity (see Harter, 2002), which thus constitutes our second extension.

Third, and possibly most important of all, the current definition lacks an elaborated theoretical concept to explore the socio-organizational context and the deeper levels beyond behavior. To meet this challenge, we review central theories that focus on the social context in leadership, including leader-member-exchange theory (LMX; Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995) and the social identity theory of leadership (SITL; Hogg, 2001). We outline how both theories make important contributions to the understanding of the social context of self-leadership. We include Schein’s (2004) concept of organizational culture as the most appropriate base for the socio-organizational frame of self-leadership. Finally, and in combining all three extensions with the current self-leadership concept, we introduce a holistic model, the self-leadership-culture (SLC).

In the second part of this article, we outline relationships of SLC with LMX and organizational identity, and derive potential positive effects of SLC to further carve out the relevance of SLC for research and practice, and show its involvement with existing theory. Discussions of future research perspectives and practical implications complete our paper.

2 THEORETICAL EXTENSIONS OF THE CURRENT SELF-LEADERSHIP DEFINITION

Self-leadership was originally conceptualized as a substitute for formal leadership (Manz & Sims, 1980). Respectively, Neck and Manz (2010) defined it as “the process of influencing oneself” (p. 4). This process is described in three primary categories including (a) behavior-focused strategies, (b) natural reward strategies, and (c) constructive thought pattern strategies (Neck & Manz, 2010). All three imply specific strategies to influence oneself to reach goals effectively. Behavior-focused strategies facilitate behavioral management via heightened self-awareness and include self-observation, self-goal-setting, self-reward, self-punishment, and self-cueing (see Neck & Houghton, 2006 for a more detailed overview). Natural reward strategies are “designed to help create feelings of competence and self-determination, which in turn energize performance-enhancing task-related behaviors” (Neck & Houghton, 2006, p. 272) and increase intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Natural reward strategies may either include building more pleasant features in a given activity or focusing on a task’s inherently rewarding characteristics while ignoring unpleasant ones (Neck & Manz, 2010). Constructive thought pattern strategies are designed to create a way of thinking, which encourages positive thinking about oneself and the task; thereby leading to better performance. Identifying and replacing dysfunctional assumptions and beliefs as well as mental imagery and positive self-talk, are the three core strategies here. It becomes clear that self-leadership is focused on internal processes of a person, compared to the external processes in traditional leadership: self-leadership thus means influencing oneself toward performance, whereas leadership means influencing others to perform (cf. Furtner, 2017).

To apply self-leadership to a broader organizational context, we deem it necessary to extent the concept of self-leadership in three regards. We describe these in the following.

2.1 First extension—acting for the good of many: Intrapreneurship

Previous conceptualizations limited self-leadership to a single person’s or a team’s goal achievement (i.e., Stewart et al., 2011), which may result in certain difficulties. Individuals or teams might, for instance, effectively follow their own goals but do not bear the broader socio-organizational context in mind. Thus, a self-leading individual may successfully reach his or her own goal, but at the same time negatively impact the group’s performance (Langfred, 2000). To avoid this negative effect, it is crucial to extend self-leadership in terms of its goal direction toward the good of a bigger socio-organizational entity. Actions of different individuals or groups may then result in mutual goal achievement efforts.

A concept that expresses behavior, which is not focused on isolated interests but rather on pushing forward the whole organization, is intrapreneurship. An intrapreneur can be described as an entrepreneur within an existing organization (Antoncic & Hisrich, 2003). In the literature, intrapreneurship is characterized by employees’ activities such as expressing initiative, taking risks, and developing novel ideas (Bolton & Lane, 2012; De Jong, Parker, Wennekers, & Wu, 2015). Pinchot (1985a) furthermore described intrapreneurship as a possibility to enable employees to joyfully express their contribution toward society.

Our understanding of an intrapreneurial aspect in SLC is similar to this. We define intrapreneurship as an expression of individuals’ behavior that is directed toward the larger socio-organizational entity. Such behavior may, but not necessarily will, lead to new and innovative solutions for the enterprise. This derives from the premise that individuals guide their behavior toward what they perceive as a positive development of the larger socio-organizational entity. As individuals orient their actions toward what they feel makes sense and recognize as the right thing to do, they are less dependent on someone to motivate them. Thus, organizational behavior no longer results from specific predefined goals and motivational efforts. Rather, everyone may actively contribute to what they perceive useful and reasonable. Having in mind traditional forms of leadership, one might think that leaders and top managers are the ones to suggest new ideas. However, we suggest that every member of the organization is seen as a potential intrapreneur, implying that everyone’s ideas are assessed by their value, irrespective of one’s hierarchy or status.

2.2 Second extension—acting in accordance with one’s deep values: Authenticity

Besides intrapreneurship, authenticity is not an explicit part of the current self-leadership literature. This is due to the equivalence of self-leadership with leadership, which we will describe in more detail now. Leadership is commonly defined as the effort to exert influence on others in order to motivate them toward achieving group or organizational goals (i.e., Northouse, 2007; Von Rosenstiel, 2003; Weinert, 2007; Yukl, 2006). This influence is directed toward changing others’ behaviors, but may also include changing others’ attitudes, values, and beliefs (Weinert, 2007). The same basic understanding of leadership is applied to self-leadership (Furtner, 2017). The only difference here is that self-leadership is directed toward oneself, while leadership is directed toward others. Consequently, a self-leader as per the current definition may change one’s own attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors in order to achieve his or her goals.

While a certain discrepancy between goals determined by the leader, and attitudes and beliefs of the followers seems plausible, such a discrepancy between self-leaders’ deeply held values and their self-set goals seems less likely. We therefore seek to emphasize that self-leadership should imply that individuals act in accordance with their inner values. Self-leaders’ words and actions are guided by their own thoughts, emotions, needs, preferences, and beliefs; hence their behavior is authentic (see Harter, 2002). One important conception of authenticity in the organizational context is authentic leadership (see Neider & Schriesheim, 2011). Aspects like (a) showing consistency between one’s beliefs and actions and (b) resisting pressures to do things, which are contrary to those beliefs, show a high consistency to our understanding of self-leadership. Concluding, the cause for action in self-leadership should lie within a person. Inner values and beliefs should therefore not be a goal for change, but rather the basis for any change.

2.3 Third extension—providing a socio-organizational frame for self-leadership: Leadership-culture

Besides introducing intrapreneurship and authenticity as two extensions of self-leadership, we consider it essential focusing on the socio-organizational frame of self-leadership. This is important, considering that self-leadership may provide solutions to current organizational challenges such as rising competitiveness or changes in technologies (cf. Baruah & Ward, 2014). Self-leadership needs to be seen through the organizational lens in order to impact organizational, and not just individual or team-level outcomes. In doing so, leadership may be perceived as a means to an end in self-leadership. That is, the role of leaders changes from directing employees toward goal achievement to enabling employees to successfully lead themselves (Manz & Sims, 1991; Stewart et al., 2011). In short, we consider leaders’ role of external leadership in self-leadership as well as the importance to see leadership through the organizational lens as important means to apply self-leadership in a broad organizational context.

In the following, we review LMX and SITL and the extent to which they are helpful in explaining the social context in self-leadership. We then explain why organizational culture can provide a more appropriate theoretical basis for self-leadership, although it is not a leadership theory as such. We apply organizational culture to the leadership context, introducing our idea of leadership-culture.

2.3.1 Leader–member exchange theory

LMX has a long research tradition and plays a central role in defining leadership as being more than leader behavior. LMX focuses on the relationship between the leader and follower dyad (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). These dyadic relationships can be of higher or lower quality. This means that leaders may develop and maintain trustful and respectful relationships with some followers but have lower quality relationships with others (Gerstner & Day, 1997). Better leader–member relationships have consistently been found to relate to more job satisfaction, more organizational citizenship behavior and better performance (for an overview see Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer, & Ferris, 2012; Martin, Guillaume, Thomas, Lee, & Epitropaki, 2016).

LMX is important but also limited regarding the exploration of the social context in self-leadership. More specifically, LMX is highly relevant when exploring the social context of self-leadership as the relationship between leader and follower is taken into account. Thereby, the focus is no longer limited to a single person. On the other hand though, LMX does not seem fully appropriate as a reference theory for the social context in self-leadership, mainly because LMX is focused, as much as limited to dyadic interactions. This limitation to dyads does not leave room to develop the full socio-organizational context we need for our expanded definition of self-leadership. One important theory that goes beyond one-on-one interactions is the SITL.

2.3.2 The social identity theory of leadership

The SITL addresses the effects of entire social groups and systems on leadership (see Barreto & Hogg, 2017; Hogg, 2001; Steffens et al., 2014). SITL is based on the social identity approach and was first published in 2001 (Hogg, 2001). Social identity is defined as “the individual’s knowledge that he [or she] belongs to certain social groups together with some emotional and value significance to him [or her] of this group membership” (Tajfel, 1972, p. 292). Individuals do not only categorize themselves and others into groups. Rather, they separate the social world into ingroups, the groups they belong to, and outgroups, the groups they do not see themselves as being part of (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987). Ingroups and outgroups are cognitively represented as prototypes, consisting of the group members’ beliefs about their group’s norms with respect to attitudes and behaviors (cf. Hogg & Smith, 2007). Within a social group, some individuals are perceived as more prototypical than others (i.e., Haslam, Oakes, McGarty, Turner, & Onorato, 1995) and highly prototypical members are liked more than less prototypical members. As we are more likely to agree with individuals we like, and to comply with their requests and suggestions (see Berscheid & Reis, 1998), it is easier for prototypical leaders to push their ideas, get them accepted within the group and lead successfully. According to SITL, and confirmed repeatedly (e.g., Barreto & Hogg, 2017; Hogg, Van Knippenberg, & Rast, 2012), prototypical members appear to exercise more influence over others and prototypical leaders are perceived as more effective than non-prototypical leaders. However, this effect mainly emerges in highly salient groups and when individuals identify with their group (i.e., Ullrich, Christ & van Dick, 2009), whereas in less salient groups or when prototypicality is low, other leadership processes such as LMX are more relevant (Hogg et al., 2005).

More recently, Haslam, Reicher and Platow (2011) have extended this perspective and suggested that prototypicality is important, albeit only one aspect of identity leadership. Leaders also gain more influence the more they actively create a group’s identity by acting as identity entrepreneurs and impresarios (for an overview see Van Dick & Kerschreiter, 2016; Van Dick et al., in press). In summary, SITL carves out how the group impacts perceptions and effectiveness of leadership and highlights the importance of social identity for leadership (Hogg, 2001).

Applied to self-leadership, it can be assumed that self-leadership can lead to success if it is part of a group’s salient identity and the leader encourages developing as sense of “us.” That is, groups may have a strong image of themselves as striving toward finishing their work autonomously. Prototypical leaders would support this idea of independence, while non-prototypical leaders would rather set the agenda, define goals, and control results. Likewise, leaders may establish new forms of self-organized ways of working as a means to carve employees’ identities.

However, there are also limits regarding the use of SITL in explaining social context of self-leadership. This is because identity per se is a very dynamic concept and not stable over time, while self-leadership and its concrete strategies are rather stable. To further illustrate the dynamic of identity, van Dick and colleagues showed that the strength of identification with a certain identity varies depending on the salience of respective group memberships (Van Dick, Wagner, Stellmacher, & Christ, 2005). The salience of these group memberships could be easily manipulated, and thus quickly be changed. Consequently, positive effects of self-leadership cannot be predicted in a stable manner if they are part of varying identity processes.

Concluding, both LMX and SITL offer valuable approaches to explain the social context of self-leadership but are also limited in their usefulness for our purpose. Besides the dyadic focus of LMX and the dynamic nature of SITL, both concepts do not consider the whole organization as their central element. Furthermore, in order for self-leadership to be developed organization-wide, we need a concept, which provides space for the concrete behaviors in self-leadership, as well as its underlying assumptions. Schein’s (2004) definition of organizational culture provides such a frame.

2.3.3 Leadership-culture

As organizational culture is not an explicit leadership concept, we will shortly introduce the original concept of organizational culture by Schein (2004), and then introduce our idea of leadership-culture, setting a clear focus on leadership aspects. Organizational culture consists of three levels, namely (1) underlying assumptions, (2) espoused beliefs and values, and (3) artifacts. Underlying assumptions define the deepest cultural level and are subconscious beliefs that guide behavior. Espoused beliefs and values basically result from experiences: a solution to a problem that has worked well in the past will be used again. Artifacts are visible, audible or touchable materializations of culture, such as dress code or office design. With the term leadership-culture, we refer to the part of organizational culture, where assumptions and behavioral norms and all other aspects of culture regarding leadership are held. We therefore see leadership-culture as one aspect of organizational culture. Based on these assumptions, leadership should also be described and analyzed on all levels of organizational culture. We therefore describe these three levels in more detail in the following.

The most basic cultural level of leadership should be concerned with the human being as such as the essence of leadership is about leading people (Schein, 2004). In the literature, the term idea of man is used to describe such assumptions about the human being (i.e., Hesch, 1997). We adopt this term and define the most basic level of leadership-culture as the idea of man. Theory X and Y are prominent examples of theories regarding the idea of man, providing concrete assumptions about the nature of human beings (McGregor, 1960). So for instance in Theory X human beings are described as rather lazy, and trying to avoid work. In Theory Y on the contrary, human beings are seen as willing to work and as able to take on responsibility.

While we described the most basic level of leadership-culture as being concerned with general assumptions about the human being, we consider the level of leadership philosophy as dealing with attitudes, beliefs, and sets of values regarding leadership. These assumptions are mainly provided by key personnel such as founders, owners, top executives, and other senior managers (cf. Bleicher, 1994; Ulrich, 1995). Similarly to implicit leadership and followership theories (Junker & Van Dick, 2014; Junker, Stegman, Braun, & Van Dick, 2016; Van Quaquebeke, Graf, & Eckloff, 2014), leadership philosophy refers to unconscious assumptions, which influence the leader–follower interaction. However, while implicit leadership and followership theories focus explicitly on ideal and typical leaders and followers, leadership philosophy focuses less on leader attributes but rather on expectations and assumptions regarding leadership. More precisely, leadership philosophy could for instance be expressed in the assumption that leaders should guide their followers’ paths or conversly, should control their work and behavior. Summing up, central assumptions about leadership are expressed in the leadership philosophy of an organization.

Artifacts, as results of the underlying idea of man and leadership philosophy, build the third level of leadership-culture. Leader and follower behaviors or other artifacts of leadership are represented on this level. Leadership theories, where certain behaviors of leaders are described, may be placed here. Providing a concrete example, an empowering leader is described as someone who “explains company goals” (Arnold, Arad, Rhoades, & Drasgow, 2000, p. 269). If such a behavior is not limited to a single leader but rather represents a behavioral norm within an organization, “explaining company goals” would represent an artifact.

The three levels of Schein’s (2004) model of organizational culture reciprocally influence each other. Transferred to our newly developed concept of leadership-culture, the following relationships result. The idea of man shapes the way we think about and design leadership and collaboration—the leadership philosophy. This, in turn, results in specific expressions of our actions, the behavioral artifacts. Those artifacts on the other hand, which are perceived by employees, will influence their way of thinking about collaboration and leadership over time. The leadership philosophy, in turn, can change the idea of man. In this way, the three levels are not independent, but they permanently interact, shape, and change the respective others in a dynamic process.

The described idea of leadership-culture is a framework that could generally be applied to a variety of leadership concepts. In the following, we will use this frame to define our concept of SLC.

3 INTEGRATING THE EXTENSIONS: SLC

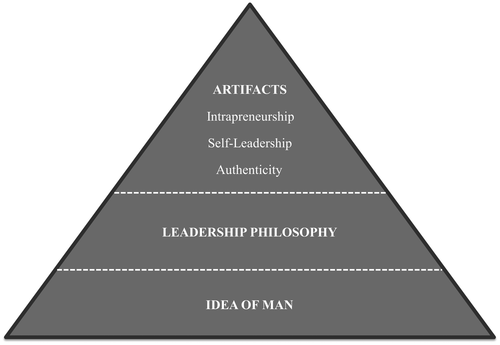

A visual representation of the integration of all three extensions to SLC can be seen in Figure 1. In the following, we present this integrated perspective in more detail.

3.1 Artifacts in SLC

At the most visible level of SLC, the leadership artifacts level, employees show intrapreneurial behaviors, act authentically, and use effective strategies to reach their self-set goals (traditional self-leadership). Intrapreneurial behavior is expressed in employee behavior, which is directed toward a positive development of a larger socio-organizational entity and which is not limited to a certain group of people within an organization. Authentic action means behavior, which is in accordance with one’s inner values and attitudes. Change and development efforts are therefore always motivated from within the person and not solely from external forces. Effective strategies for goal achievement include all current elements of self-leadership, namely (a) behavior-focused strategies, (b) natural reward strategies, and (c) constructive thought pattern strategies (Neck & Manz, 2010). Leadership artifacts are not limited to these three descriptions of artifacts. Rather, individuals and companies will have various different solutions on how to become self-leading. For instance, employees may take on responsibility or actively ask for information they need for a certain issue to become transparent.

3.2 Leadership philosophy in SLC

How do individuals in SLC think about the role of leaders? We propose that leaders in SLC are seen as facilitators of SLC. That is, their main leadership task is to enable followers to lead themselves. Ways to achieve this aim will differ from case to case, depending on earlier experiences (cf. Schein, 2004). However, we expect existing concepts to come very close to our idea of leadership philosophy in SLC.

We consider servant leadership (Greenleaf, 1977) and SuperLeadership (Manz & Sims, 1991) as the most relevant concepts for the leadership philosophy in SLC. A servant leader may be described as providing followers with the information they need to do their work well or as encouraging followers to use their talents and to come up with new ideas (Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011). Furthermore, servant leaders provide decision authority, enable followers to solve problems themselves, and offer abundant opportunities to learn new skills. This general idea is shared by SuperLeadership (Manz & Sims, 1991). SuperLeaders focus explicitly on the goal to enable their employees to lead themselves. Furthermore, they work toward establishing a culture of self-leadership within an organization. While SuperLeadership is focused on self-leadership strategies solely, leadership philosophy in SLC also contains intrapreneurship and authenticity. Another difference is that both servant leadership and SuperLeadership describe concrete behaviors (artifacts), while the leadership philosophy level in SLC rather focuses on shared expectations about leadership.

3.3 The idea of man in SLC

The most basic level of leadership-culture is the idea of man. It is difficult though, if not futile, to determine a specific idea of man which every employee of SLC will share. Yet, assumptions about the idea of man shared by many employees can be made in order to endorse self-leadership. In the following, we will introduce some notions on the idea of man, which fit nicely to our concept of SLC.

Hesch (1997) proposed one such idea of man prevailing in modern organizations. He described human beings as creative and capable of self-leadership. He further assumed that individuals possess the necessary abilities to lead themselves, such as being empathic, communicative and cooperative, autonomous and self-confident, as possessing social skills and being able to act responsibly. This reasoning is very much in line with recent thinking in Economics by Akerlof and Kranton (2005), who point out that the old model of control is costly and signals mistrust, whereas supervisors who trust their employees create a strong identity and will achieve their goals more effectively.

Quite similar to these ideas are some general assumptions of Theory Y (McGregor, 1960). Theory Y, for instance, proposes that whether or not human beings perceive their work as a source of satisfaction and carry it out voluntarily, as opposed to being motivated by avoidance of pain or punishment, depends on malleable conditions. These conditions may, for instance, be the way employees are led or the degree of freedom in designing their work. Furthermore, individuals show self-discipline and self-control toward goals that they feel obliged to do, which is why external control and sanctions are not seen as the only means to foster employees’ engagement for organizational goals. The strength of goal commitment is described as being mainly dependent on the possibility to perceive appreciation and strive toward self-actualization. Finally, under good conditions, individuals strive toward gaining responsibility. Escaping responsibility, lacking ambition, as well as striving for security, are seen as being primarily a result of bad experience, and not inherent human characteristics. Summing up, in Theory Y suggested that conditions can be influenced in such a way that they support, for instance, independence, self-control, and goal commitment of employees.

With all this in mind, we assume that individuals in SLC believe that most employees in their company would want to strive to lead their own lives in a free and independent manner, and generally possess the capabilities to do so if provided suitable conditions and possibilities. Pursuing this further, there seems to be an “unlimited faith that, if given the opportunity to perform, most people will come through for them” (Manz & Sims, 1991, p. 34).

In a SLC, individuals strive toward leading one’s own (working-)life in a free and independent manner. They act in accordance with their inner values and beliefs, bearing the development of a larger socio-organizational entity in mind, and using effective self-leadership strategies for goal achievement. Leaders are seen as facilitators of these behaviors, namely authenticity, intrapreneurship and self-leadership.

4 RELATIONS AND OUTCOMES OF SLC

To gain a thorough understanding of SLC, we will now take a closer look at the social processes in SLC. More precisely, we will analyze how central theories in this area—namely LMX and organizational identification—may possibly interact with SLC. As there is currently no research regarding our definition of leadership-culture, we focus on the effects of organizational culture, referring back to the fact that leadership-culture is defined as part of organizational culture. We then apply the described results to SLC. Furthermore, we outline how SLC may positively affect organizational life, such as job satisfaction and performance. We derive these positive effects relying on research that displays positive outcomes of several elements of SLC, like self-leadership and Theory Y.

4.1 Delving deeper into the social processes constituting SLC: Possible relations with LMX and organizational identification

Organizational culture and servant leadership serve as indicators for a possible influence of SLC on LMX. Several studies analyzed how LMX and organizational culture interact (for an overview see González-Romá, 2016). The basic assumption regarding the organizational culture and LMX relationship is that organizational culture can be a contextual factor that influences LMX development (Dienesch & Liden, 1986). More precisely, shared values and assumptions may promote certain leadership behaviors that fit the characteristics of high-quality LMX relationships (Erdogan, Liden & Kraimer, 2006; Graen, 2003; Major, Fletcher, Davis, & Germano, 2008). That is, high-quality relationships are more likely to result from organizational cultures that emphasize and value leader–follower exchanges. To further strengthen our argumentation of a positive influence of SLC on LMX, we take a closer look at servant leadership. Barbuto and Heyden (2011) found that all facets of servant leadership correlate highly with LMX. As described earlier, servant leadership overlaps highly with our leadership philosophy in SLC. Concluding, organizational culture, in general, influences LMX, and more specifically, SLC may influence LMX positively, due to its empowering and supporting aspects, which can be seen as similar to servant leadership.

Similarly, SLC and identification processes might positively influence each other. We assume this from research findings which showed that people identify more strongly with those parts of their identity that are salient. More specifically, teachers identified more strongly with either their school or their occupation, depending on which of these two were (manipulated to be) salient (Van Dick et al., 2005). Hence, people will identify more strongly with their organization, when the organization´s identity is salient. Besides this influence of organizational cultural salience on identification, Hatch and Schultz (2002) describe a model explaining how organizational culture and organizational identification mutually influence each other. Regarding the influence of identity on culture, they describe a reflection process as relevant. More specifically, when employees reflect on their organizational identity, they activate deep organizational values and assumptions. These will be reinforced or changed through the reflection process. An organization’s culture, on the other hand, provides information, which is used by organizational members for organizational identification processes. Deeply held values and assumptions provide concrete information, which is used for the construction of one’s organizational identity. Building on these arguments, and relying on the idea that SLC is part of an organizational culture, it can be assumed that SLC and employees’ organizational identity similarly reciprocally influence each other.

4.2 Diving deeper into the impact of SLC: Delineating potential outcomes

While the interaction with other constructs is important for a thorough understanding of SLC in research, practice will be mainly interested in outcomes of SLC. More specifically, investments in SLC will only be considered, if positive outcomes are expected. Therefore, we will now introduce some potential positive outcomes of SLC.

Recent research showed that self-leadership influences job satisfaction positively via knowledge sharing (Kyoung-Joo, 2017) as well as in form of individual self-management (Uhl-Bien & Graen, 1998). Furthermore, positive associations between empowerment and job satisfaction have been found (Seibert, Wang, & Courtright, 2011; Ugboro & Obeng, 2000). While self-leadership is part of the leadership artifacts level, empowerment can be seen as part of the leadership philosophy in SLC. We therefore argue that SLC will have a positive influence on job satisfaction.

Theory Y-based management style supports organizational citizenship behavior (Gürbüz, Şahin, & Köksal, 2014). Moreover, intrapreneurship (i.e., Gawke, Gorgievski, & Bakker, 2017) and self-leadership (Park, Song, & Lim, 2016) positively affect work engagement. Consequently, we propose that a combination of these elements in SLC will increase employees’ work engagement.

We furthermore assume a positive association of SLC with performance as several elements of SLC have already been demonstrated to benefit performance. That is, Chen, Zhu and Zhou (2015) showed that servant leadership influences service performance positively, partially mediated by self-efficacy and group identification. Seibert, Wang, and Courtright (2011) demonstrated that empowerment is positively associated with task and contextual performance. Moreover, self-leadership trainings were shown to positively influence subjective and objective performance outcomes (Frayne & Geringer, 2000; Lucke & Furtner, 2015).

With regard to the current challenges organizations face, we will now look at innovation as a possible outcome of SLC. We consider innovation as central to organizational success, as one important challenge for organizations is their need to be flexible and adapt to changing demands in order to remain competitive (cf. Baruah & Ward, 2014). We argue that innovative behavior will be a positive outcome of SLC, building on Denison’s (1990) model of organizational culture that suggests adaptability and involvement as two dimensions of organizational culture, which overlap with ideas of SLC as follows and were shown to be associated with innovative behavior (Sinha, Priyadarshi, & Kumar, 2016). Adaptability describes how well organizations react to changing wishes and needs of customers and the market place (Denison, 1990). Adaptability therefore reflects the intrapreneurial component of SLC to some degree, which describes how individuals in SLC focus their work on what they consider best for their organization. Involvement describes how well organizations empower their employees, build teams, and develop employee’s capabilities (Denison, 1990). Involvement is central to SLC, as employees are empowered to lead and develop themselves. Hence, innovative behavior should result from SLC.

Concluding, we assume that SLC has relations with LMX and organizational identification. Furthermore it should have positive influences on job satisfaction, work engagement, performance, and innovative behavior. Thus, SLC can be considered an important concept for research and practice.

5 DISCUSSION

We introduced the concept of SLC and by doing so we intended to provide a holistic model, which can be used to understand the socio-organizational context in self-leadership and to provide practitioners with an idea of how to organize a large number of self-leading individuals in an organization. We integrated SLC with existing approaches, namely LMX and organizational identity by describing relationships between these three concepts. Finally, we proposed positive outcomes of SLC.

5.1 Future research perspectives

For a further analysis of SLC, the concept needs to be operationalized. To do so, we suggest to build on existing constructs, that are proposed to be either part of SLC, or similar to it, and adopt these items based on theoretical assumptions so that they fit the concept as a whole. More specifically, a variation of the Authentic Leadership Inventory (Neider & Schriesheim, 2011) in which the items are formulated as “I …” instead of “my leader …” may be used to operationalize authenticity in SLC. The focus would then rest on the self-leading capabilities of every employee, rather than solely leaders’ behaviors. Moreover, existing inventories to assess servant leadership might be suitable. After an initial item selection, a reduction of items can be achieved in a second step. We would suggest following a similar procedure as used for the development of short scales, such as the Abbreviated Self-Leadership Questionnaire (Houghton, Dawley, & DiLiello, 2012). This would imply selecting items with the strongest factor loadings from each dimension of the selected constructs in a first step, conducting an exploratory factor analysis with new data in a second step and then computing a confirmatory factor analysis in the third step, to replicate the structure found in the exploratory factor analysis. Alternatively, items could be reduced based on theoretical fit with SLC.

After developing such an instrument, it is most important to test the empirical relevance of SLC and the proposed positive effects in a next step. It will be difficult, if not impossible to find two truly comparable companies, out of which one is high in SLC, and the other one is not. Therefore, the effects of SLC should be researched using a variety of approaches. This may imply experimental or quasi-experimental designs, including a manipulation of SLC and the measurement of differences in outcomes between high and low SLC groups versus control groups (for a similar approach in authentic leadership, see Ciani, Hannah, Roberts, & Tsakumis, 2014). Also, longitudinal designs with at least two measurement points may be considered suitable (cf. Boamah, Read, & Spence Laschinger, 2017). Thereby it is important to include a broad sample with regard to industry, age or position. There is another approach to further discover SLC, which might be interesting, because, as Bryman stated in 2004, “leadership research has been and almost certainly still is a field that is dominated by a single kind of data gathering instrument—the self-administered questionnaire” (p. 731). We therefore suggest using in-depth qualitative interviews in organizations with a presumably high or, at the other end, extremely low SLC. Using such an approach would allow to discover relevant mechanisms through which SLC unfolds its positive effects and potential moderators of these relations.

In addition to this theoretical advancement of SLC and the test of its empirical relevance, future research might explore beneficial personal skills and characteristics within a SLC. Dietz (2008), for instance, introduced a broad number of requirements for self-leadership on the individual level. These are clustered into the three aspects of (a) thought, (b) feeling, and (c) will/action. Thereby, a focus is set on entrepreneurial thinking, corresponding with our idea of intrapreneurship, and implying aspects like dealing with complexity and taking an eagle-eye perspective. Furthermore, the need for autonomy may play an important role in unfolding the positive effects of SLC. Individuals with a high need for autonomy are more likely to engage in self-leadership, compared to individuals with a lower need for autonomy (Yun, Cox, & Sims, 2006). Optimism is another quality, which has shown to help maintaining an outlook of hope and passion for individuals (e.g., Frankl, 1984). Besides optimism, locus of control can be related to SLC. It has been described that self-leaders and entrepreneurs rather believe that they can control events and outcomes in their own lives, therefore having an internal locus of control (for self-leadership see Williams, 1997; for entrepreneurship see Perry, 1990; Shapero, 1975), and engage more in self-leading activities.

Besides self-leadership of individuals in the organizational context, self-leading teams recently gained high popularity with the rise of agile methods like Scrum (Cohn, 2010). Supporters of the Scrum method claim positive effects for Scrum teams in comparison to traditional development teams, mainly referring to the success story of Salesforce.com: Higher quality of work, more satisfied customers and employees, and a faster time-to-market (i.e., Greene, 2008). Scrum is mainly designed for tasks where solutions need to be developed, and less for routine tasks. Team self-leadership as practiced in such Scrum teams is associated with increased performance but only for teams, which engage in conceptual tasks and not in behavioral tasks (Stewart & Barrick, 2000). Furthermore, Scrum supports certain aspects of working life, which are also linked to positive effects of self-leading team performance: low levels of centralization (Tata & Prasad, 2004), empowerment climate, where information sharing and autonomy are important (Seibert, Silver, & Randolph, 2004), as well as cultures, where employees are provided with work-related information and power to take work-related decisions themselves (Spreitzer, Cohen, & Ledford, 1999). However, self-leadership in teams has not only positive effects. Stewart et al. (2011) describe that “a great deal of internal control for teams may impede internal control for individuals in some circumstances” (p. 211). Research may therefore further analyze the relationship between individual self-leadership and team self-leadership and SLC, and determine under which circumstances they enrich or impede each other. Furthermore it would be interesting to explore, whether SLC may positively interact with the effectiveness of Scrum teams, and how this form of project management and work organization influences organizational life, culture, and especially the role of leadership.

5.2 Challenges for SLC in practice

SLC implies a change in how supervisors lead their subordinates. This might provoke resistance among both supervisors and subordinates. Leaders, for instance, describe it as difficult to treat individuals in the way they want to be treated, as leaders may have the tendency to strive for control (see Manz & Sims, 1991). Furthermore, followers may ask for more help and support from their leaders, which makes it difficult for them not to tell their followers to do the right thing. This challenge may even get harder, when followers make (serious) mistakes. A certain latitude for followers in making mistakes however, is seen as critical for the success of self-leadership and likewise for SLC. Lastly, not every follower seeks the same degree of self-leadership opportunities. Consequently, leaders need to adjust their expectations to individual job experience, skills, and abilities (Manz & Sims, 1991). Future research may identify central elements that help leaders meeting these challenges.

Another potential threat of SLC may be the danger of a misuse, whenever it is not truly based on a mindset that is focused on the interest of human beings in the first place. This happens when employees strongly identify with their companies, are proud to work there, and feel empowered to work independently. At the same time though, employees may engage to an above-average extent to move the company forward and to reach goals. Through this engagement, there is a certain danger that employees will exceed their limits based on their own desire to do good for the company and through high identification (Avanzi, van Dick, Fraccaroli, & Sarchielli, 2012). Therefore, growth should always be determined considering resources and aiming for a sustainable pace of development, mindful of the interests, and limits of employees.

6 CONCLUSION

Self-leadership gains importance in the light of present organizational challenges. With our proposition of SLC, we expanded the view of self-leadership that was, so far, limited to goal achievement of single individuals or teams. We developed a holistic approach to self-leadership, which can be used to gain a deeper understanding of the socio-organizational context. Practice may benefit from SLC, as it provides an approach for a fruitful collaboration between/among self-leaders. Thinking one step ahead, by applying SLC outside of organizations, the wider society may benefit from individuals who direct their behavior toward the good of the community and not only toward what is best for themselves.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Eva Bracht was supported with a PhD stipend by the Heinrich Böll foundation.