A resource dependence perspective on intergroup conflict: The synthesis of two theories

Abstract

Intergroup conflict is a pervasive issue at the heart of concern for organizations and society alike. Currently, there is little consensus about the impetus for intergroup conflict. Micro approaches focus on behavioral aspects of individuals, personality factors, and characteristics of group composition, whereas macro theories explain the reason for tension as competition as the factors within the external environment that contribute to differences in power. In this article, I offer a Resource Dependence Perspective on intergroup conflict (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978), which focuses on the strategic actions undertaken to manage dependencies with other entities in their environment, and synthesize the two theoretical perspectives into a single more comprehensive view of intergroup conflict. I offer propositions, a theoretical model, and discuss implications for research and practice.

1 INTRODUCTION

Conflict has been a fundamental part of human interaction since the beginning of history. It can be as benign as a sibling rivalry or as malignant as a world war. It may involve two people or two billion people and its duration is equally unfixed. Although the manifestations of conflict vary across time and space, it remains an ever-present facet of our lives. In the fiercely competitive organizational landscape of the 21st century, where economic winners and losers are commensurately rewarded or punished in an increasingly short time span, conflict among companies, departments, teams, and individuals is ubiquitous and intense. However, in order for businesses to function and turn a profit in today's global economy, both intergroup and interorganizational cooperation and collaboration are increasingly necessary. Therefore, from an organizational behavioral perspective, understanding the origins of conflict, and how it transpires within and between organizations, is crucial.

We draw from the organizational theory literature to define conflict herein as a two-pronged interaction that begins with a difference of opinion and subsequently leads to a corresponding behavioral response from one of the involved parties. In our view, a disagreement that is wholly internalized and does not lead to pushback is the mere failure of two minds to meet, and lacks the behavioral element commonly associated with conflict. Our definition is supported by existing literature associating conflict with a “breakdown” (March & Simon, 1958) and an “episodic, outcome-oriented struggle” that is “marked by efforts at hindering, compelling, or injuring and by resistance or retaliation” (Katz & Kahn, 1978). However, our definition is not inconsistent with the transformative view of conflict management (Folger & Bush, 1996), as the pushback in response to a disagreement may conceivably be constructive or healing in nature, leading to a win-win outcome for both groups.

Within organizational studies, the micro, meso, and macro domains all address the ever-present conflict phenomenon, yet they do so in different ways. For instance, the micro and meso approaches usually focus on behavioral aspects of individuals (De Wit, Greer, & Jehn, 2012; O'Neill, Allen, & Hastings, 2013), personality factors (Bradley, Anderson, Baur, & Klotz, 2015), characteristics of group composition (Bendersky & Hays, 2012, Fehr, Zheng, Tai, & Gelfand, 2015; Okimoto, Wenzel, & Hornsey, 2015) and aspects of the type and source of the conflict itself (Bradley et al., 2015; Weingart, Behfar, Bendersky, Todorova, & Jehn, 2015). Conversely, macro theories tend to explain the reason for tension, competition, and conflict between organizations in terms of the availability of resources (Hillman, Cannella, & Paetzold, 2000; Hillman & Dalziel, 2003), power asymmetry (Pache & Santos, 2013; Purdy & Gray, 2009; Santos & Eisenhardt, 2009), uncertainty (Davis & Cobb, 2009), and factors within the external environment such as group dynamics and competitive pressure (Anthony et al., 2005; Boyd, 1990; Scott & Davis, 2007). Despite their differing levels of analysis and terminology, however, we argue that the micro, meso, and macro perspectives have substantial conceptual overlap. Thus, we propose that they actually complement one another, and taken together, are likely to provide a more complete understanding of intergroup conflict than any one perspective does separately.

Specifically, in this article, we address the topic of intergroup conflict from the micro, meso, and macro structural levels and discuss how two organizational theories approach the impetus for conflict from different perspectives, yet can be synthesized to form a more complete model. Our framework adopts an ecological approach (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) toward understanding social conflict, as other conflict scholars from the developmental psychology, sociology, evolutionary biology, economics, and communications fields have undertaken (Cummings, Goeke-Morey, Merrilees, Taylor, & Shirlow, 2014; Dubow, Huesmann, & Boxer, 2009; Oetzel, Ting-Toomey, & Rinderle, 2006; Rus, 2012; Zajitschek & Connallon, 2017). Our approach is also aligned with conflict as examined within the management literature, as it incorporates aspects of conflict theory and recent extensions of resource dependence theory (RDT; Davis & Cobb, 2007; Drees & Heugens, 2013) and realistic group conflict theory (RGCT; Brief et al., 2005). Finally, the Baum, Locke, and Smith (2001) multilevel model of firm growth supports the structural framework proposed here, as it likewise integrates theoretical perspectives from the individual, organizational, and environmental levels. While our article is not the first to adopt a multilevel perspective to examine conflict, it is the first known study to integrate RDT with RGCT into a cohesive model.

In the following sections, we first introduce RGCT (Brief et al., 2005; Sherif, 1961), a micro- and meso-theoretical explanation for intergroup conflict, which may occur among departments, project teams, and office locations. Second, we discuss RDT (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978), which explains the rationale behind the formation of organizational interdependence, focusing on the strategic actions undertaken to manage these dependencies within the environment. We also consider Emerson's (1962) theory of social power, as it was one of the micro-level underpinnings of RDT and may therefore serve as a useful conceptual bridge for the differing structural levels of analysis within RGCT and RDT. We then proceed to synthesize the RGCT and RDT theoretical elements that are salient to interorganizational groups into a single comprehensive view of intergroup conflict. Lastly, we offer propositions based on our proposed resource uncertainly conflict model (RUCM) and discuss implications for both research and practice.

2 REALISTIC GROUP CONFLICT THEORY

RGCT (Sherif, 1961) is a foundational framework that addresses the phenomenon from both a micro and meso perspective. It explains functional relations between social groups (Sherif, 1966) through a social psychological lens. Specifically, posited and Sherif (1961) tested the notion that intergroup hostility stems from competition that was motivated by rewards, which are extrinsic to the group. The theory predicted that opposing group interests in obtaining scarce resources would promote competition, whereas interdependent and supraordinate goals would facilitate cooperation. RGCT, therefore, explains how contrasting interests can lead to behavioral responses that are characteristic of conflict in the context of intergroup competition.

Interestingly, Sherif (1961) observed that intergroup antagonism not only sprang from competition over scarce resources, but also increased the identification and attachment among in-group members toward each other. Sherif's (1961) seminal Robbers Cave Experiments illustrated how RGCT was capable of incorporating both intrapersonal and interpersonal perspectives together to better understand conflict. It showed that people have a deep need to maintain esteem through identification with their in-group, and that individuals can easily be made to create in-group/out-group categories based on arbitrary distinctions. It also revealed that competitive intergroup activities generated hostility toward out-group members, despite the remarkable triviality of group affiliations. At the same time, the observed hostility also facilitated the attachment of in-group members with each other. Taken together, the body of work resulted in the understanding that an environment of competition could be transformed into collaboration with the introduction of supraordinate goals.

Thus, RGCT introduced a more nuanced and multifaceted framework for understanding sources of conflict between groups which relied on more complex factors than those of basic interpersonal motivation (i.e., food, safety, sex, etc.) such as incompatible goals and competition over limited resources. While most scholars now regard RGCT as a seminal set of ideas regarding intergroup interaction, at its conception, RGCT represented a counter-culture push away from social exchange theories, which were much more widely accepted at the time. Critics of the “exchange perspective,” for instance, believed they oversimplified group interaction and relied too heavily on theories of animal behavior to explain interpersonal human interaction.

Alternatively, RGCT built on extant theories of intergroup behavior that were focused primarily on interpersonal, intragroup, or intrapsychic explanations of conflict (Sherif, 1966; Sherif, Harvey, White, Hood, & Sherif, 1960; Sherif & Sherif, 1953). For instance, at the time it was conceptualized, RGCT was proposed as an alternative to Authoritarian Personality Theory (Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, & Sanford, 1950), the Frustration-Aggression Framework (Dollard, Doob, Miller, Mowrer, & Sears, 1939), and the Contact Hypothesis (Allport, 1954), all of which focused on intrapersonal psychic processes. Thus, RGCT was one of the first social psychological theories of conflict that was not based purely on micro-theoretical explanations. For this reason, it is not surprising that several groups of scholars were critical of the framework during its early years.

In terms of its critics, RGCT has received some pushback from social psychologists for its lack of attention to the underlying mechanisms that stopped short of explaining the inherent motivation for group members to seek in-group attachment with each other (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). In other words, RGCT accurately predicted that group members would seek attachment under certain conditions, but some believed that it failed to adequately elucidate how and why this was true. Thus, several “critics” seemed to actually find the initial framework useful, but incomplete, and built on the ideas proposed and tested by Sherif & Sherif (1969) through the addition of components that elaborated on the mechanisms. Many subsequent critics also tested it against other competing and parallel social psychological ideas to try to ascertain its explanatory capacity.

Despite the criticism, many scholarly domains have since adopted and integrated the RGCT framework into their theoretical perspectives. For instance, recent applications of RGCT have laid the foundation for topics such as organizational diversity and cross-cultural management (Baumeister & Vohs, 2007; Brief et al., 2005; Esses, Jackson, & Armstrong, 1998). Several theories within the domain of organizational diversity and cross-cultural management draw on aspects of RGCT to support the idea that opposing factions within and organization can be brought together using supraordinate goals and encouraging identification with in-group attributes and characteristics. Another field that utilizes core elements from RGCT is the abundant research on faultlines, or the alignment of individual member characteristics into the formation factional groups. Specifically, this body of work investigates the effect of faultlines on conflict and subsequently group performance, drawing from several of sources of conflict identified by RGCT.

In sum, RGCT and Sherif's experiments provided the foundation for much of the current micro and meso conflict-related organizational topics, conceptual support for the conditions under which groups engage in behaviors characteristic of conflict, as well as the basis for group conflict within our model. At its origination, RGCT was a pioneering social psychological perspective that transcended existing boundaries to accurately predict several of the dynamic situational complexities that generated intergroup competition and collaboration.

3 RESOURCE DEPENDENCE THEORY

From the macro perspective, RDT posits that social control arises amid the interorganizational struggle for power and dominance. The theory, as Pfeffer and Salancik (1978, p. 14) describe it in their seminal book The External Control of Organizations, is specific to large publicly traded firms and predicts that, “organizations will attempt to manage the constraints and uncertainty that result from the need to acquire resources from the environment.” RDT posits that certain organizations have more power than others because of the, “particularities of their interdependence and their location in social space” (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978, p. 13). The theory identifies how an organization's access to critical resources and autonomy affect the extent to which one organization is dependent on another (Hillman, Withers, & Collins, 2009; Oliver, 1991). An organization's attempt to restore autonomy arises out of its asymmetrical access to resources, which can generate new patterns of interdependence and power imbalances, also known as dependence asymmetry (Gulati & Sytch, 2007). Power or dependence asymmetry, defined as the extent to which one organization perceives that it is more powerful than a peer (Casciaro & Piskorski, 2005; Gulati & Sytch, 2007), impacts its strategy for managing exchange relationships, and influences its adoption of a collaborative versus competitive stance. Specifically, as the power imbalance increases, the weaker organization faces increasingly undesirable exchange conditions, leading to conflict (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978, pp. 66–67).

RDT is conceptualized at the organizational level of analysis, with firms posited to comprise “the fundamental units for understanding intercorporate relations and society”. Notwithstanding its explicit focus on large organizations, the foundation of RDT emerged in part from micro- and meso-level conceptualizations (Hillman et al., 2009) such as Emerson's (1962) theory of power relations. Emerson proposed that social power was not a static phenomenon, but was instead a ratio derived from “ties of mutual dependence” capable of shifting over time. His theory was posited to apply to relationships at the individual or group level. Emerson (1962) proposed that social power was inexplicably bound to implied mutual relationship dependencies (parent to child, home builder to mortgage lender, etc.). He suggested that the degree of power imbalance could change based on two factors analogized to supply and demand, “availability” and “motivational investment” (Emerson, 1962, p. 33). Emerson's conceptualization of a dynamic, relationship-determinate power network and resource “availability” (supply) are paralleled in the subsequent macro-level RDT, which posits that organizations are “constrained by network interdependencies with other organizations” and take actions leading to “new patterns of dependence”, similar to the dynamic nature of Emerson's power relationships between individuals. RDT also posits that an organization's existence hinges on control over limited environmental resources, in parallel to Emerson's emphasis on resource availability. The recognition that dependencies shift over time is also shared by the Emerson (1962) and RDT perspectives.

Emerson (1962) theorized that the cultivation or denial of “alternative sources” for a dependency were potential “balancing operations” for a relationship lacking parity. Such “balancing operations” include the withdrawal of interest, the development of additional network connections by the weaker party (e.g., a home builder locating new potential mortgage lenders to escape a monopoly situation), coalition building, and the conveyance of status to the stronger party at a low cost to the weaker party (Emerson, 1962). Emerson's “balancing operations” at the individual level also have macro counterparts within RDT. Specifically, Pfeffer and Salancik (1978, pp. 108–115) posited that organizations faced with a dependency situation elect to either accept the imposed restraint or else modify their environment by seeking out other sources, stockpiling, pursuing a diversification strategy, merging with another entity, joint venturing, or adopting a cooptation approach such as granting the outsider organization a board seat. The conceptual similarities between Emerson's (1962) micro- and meso-level theory and RDT's macro-level theory offers plausible support for the integration of macro concepts into our proposed intergroup conflict theory, as it suggests that macro-level manifestations of conflict are rooted in micro- and meso-level social interactions.

In further support of multilevel conflict theory integration, scholars in social psychology studying the dynamics of interdependencies (i.e., Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959) were among the first to elucidate the joint form of dependence in interpersonal relationships (Lawler & Yoon, 1993, 1996). This concept has also branched into organizational behavioral explanations for intergroup conflict and has been extended to inter and intraorganizational contexts (Bradley et al., 2015; Gulati & Sytch, 2007; Weingart et al., 2015). As a central tenant, RDT states that organizational behavior is constrained and shaped by the demands and pressures of the organizations and interdependencies between these groups that exist in the environment. Thus, it is an open systems approach, and three aspects of the environment in particular are critical for determining the dependence of one organization on another. First, the importance of the resource or “the extent to which the organization requires it for continued operation and survival” (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978, p. 45) is a crucial factor. The second aspect is the extent to which one entity has control over the resource and is in charge of its use (i.e., an interest group). Finally, the number and availability of alternatives to the resource is also crucial for determining an organization's dependence on other groups and organizations in the environment. When one organization or group exerts control over a critical resource of another, the resulting power imbalance serves as a constraining mechanism on the latter's behavior (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978, pp. 59–60).

Another important aspect of RDT is that, according to Pfeffer and Salancik (1978), every organization seeks to maintain itself, negotiate its position within the environment, and survive. Survival is defined as, “the extent that the activities included within the organization are sufficient for the organization to maintain itself,” and the organizational boundary is identified as, “the total set of … activities in which it is engaged … and has the discretion to initiate, maintain, or end” (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978, p. 32). Thus, a firm's struggle for survival is a critical factor and powerful impetus for its relationship with other entities in the environment. Further, Pfeffer and Salancik (1978, p. 258) also posit that “survival of the organization is partially explained by its ability to cope with environmental contingencies and negotiate exchanges to ensure the continuation of needed resources.” In their recent study of mergers and acquisitions, Casciaro and Piskorski (2005) present empirical support for a reformulated RDT. Specifically, they find that mutual dependence is a key predictor of mergers, whereas power imbalance is an obstacle. This result is consistent with Pfeffer and Salancik's (1978) general proposition that to reduce environmental uncertainty, organizations will strategically manage their interorganizational relations.

4 TOWARD A UNIFICATION OF TWO PERSPECTIVES

We believe the intergroup conflict literature would gain theoretical depth from an integration of the meso RGCT and macro RDT perspectives. Blending these theories would provide a more holistic perspective on the influences and underlying causes of intergroup conflict, thereby strengthening our understanding of the phenomenon. Our approach considers the micro-level conceptualizations (e.g., Emerson, 1962) from which RDT emerged (Hillman et al., 2009), reflecting on the theory's conceptual origins in order to plausibly align its structural elements with the meso-level RGCT. We conceive of intraorganizational conflict as the product of intense struggles over scarce resources (i.e., time, money, personnel, and equipment), with variating levels of power and control. Specifically, we view it as an outcome of in-group/out-group biases and prejudices, with competition serving as the ultimate consequence of strategically managed interdependencies developed as contingent responses undertaken to ensure the group's survival. Our perspective on conflict hinges on a two-pronged process that begins with a disagreement (struggles over asymmetrical control of scarce resources) and leads to a corresponding behavioral reaction (contingent responses).

RGCT (Sherif, 1961) and RDT (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978) explain group and firm interactions using different frames of reference and levels of analysis. RGCT explains intergroup conflict as a result of in-group/out-group tensions, an outcome of prejudice and hostility by means of competitive behavior, and as a manner of demonstrating loyalty and affiliation for one's in-group. RDT, conversely, explains how firms develop interdependencies as a result of their need for scarce environmental assets in an uncertain environment and how these interactions lead to power differentials, competition and coordination among firms. Despite the contrast in structural levels between these two theories, we propose that RDT can be synthesized with RGCT to better explain intrafirm conflict than either approach is capable of doing alone.

Although the two theories have different origins, and rely on different methods and levels of analysis, substantial overlap exists between them and they both speak to the same phenomena—namely, the precursors to intergroup conflict. For instance, both theories view intergroup competition as a result of a group's attempt to maintain sufficient resources for survival. Further, RDT and RGCT both explain differences in power as the product of zero-sum relationships with mutually exclusive goals. For instance, the Robbers Cave Experiment (Sherif, 1961) demonstrated that mutually exclusive goals and negative interdependence result in a competitive environment and ultimately leads to conflict between groups. By contrast, when the goals are supraordinate and interdependence between the groups is necessary, a cooperative environment ensues.

Under the RDT perspective, the sharing of resources by two firms is also understood to not be exclusive of cooperation; in other words, mutual dependency is not always a zero-sum game. Pfeffer and Salancik (1978, p. 41) found that “the dependence of one organization on another need not be competitive … symbiotic interdependence exists when the output of one (organization) is the input for the other,” and when this occurs “interdependence … can facilitate the ability of both organizations to meet its goals.” The foregoing perspective parallels Emerson's (1962) concept of shifting “ties of mutual dependence” between individuals that reflect mutual dependencies (e.g., parents and children) that vary over time. RDT focuses on how the position of organizations and their control over scarce environmental resources dictates their power (and chances for survival) within a social context. Although Pfeffer and Salancik (1978, p. 66) acknowledge that conflict is a “characteristic of organizational systems” closely linked with power and control, it is addressed indirectly as a functional response to an organization's attempt to strategically position itself and survive in a competitive landscape. The foregoing strategic responses from organizations (alternative sources, merger, cooptation, etc.) are in parallel with Emerson's (1962) “balancing operations” for individual-level power asymmetries.

Our new perspective incorporates the antecedents of competition and collaboration specified by RGCT, as well as the environmental prerequisites of interorganizational conflict outlined by the RDT perspective. With regard to the former, (a) resource scarcity, (b) performance-based rewards, and (c) the absence of a supraordinate goal are the factors that Sherif (1961) proposed lead to either conflict or collaboration. RDT also recognizes resource scarcity as a source of conflict between organizations (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978, p. 67), framing its conceptualization of the environment on (a) the importance of the resource for survival (“munificence”), (b) the amount of firm control over the resource (“concentration”), and (c) the degree and disparity of outside system control (“interconnectedness”) (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978, p. 68). In accordance with RDT, the more important the resource, the more it is controlled by an outside actor, and the more tightly and broadly it is controlled in the external environment, the greater the level of uncertainty in accessing it. The foregoing represents a nuanced approach to resource scarcity that may not be wholly applicable to individuals but is plausibly salient to groups as well as organizations.

Pfeffer and Salancik (1978, p. 42) viewed uncertainty as a conceptually distinct causal outcome of interdependency and conflict, but also acknowledged that uncertainty represents a fundamental problem arising from mutual dependence. We propose that uncertainty can plausibly be related back to encompass the primary structural dimensions of the environment identified in RDT—munificence, concentration, and interconnectedness—and are also expressed in the three aspects of the environment deemed critical for determining mutual dependence—resource importance, resource scarcity, and the availability of alternates. Under our integrative perspective, the foregoing three aspects of the environment (importance, scarcity, and availability of alternates) are recast as dimensions of resource uncertainly, which we propose as a critical antecedent to intergroup competition. In the next section, we explicitly outline the proposed model and explain how it expands our current understanding of group conflict.

5 A MODEL OF INTERGROUP CONFLICT INFLUENCED BY RESOURCE DEPENDENCE

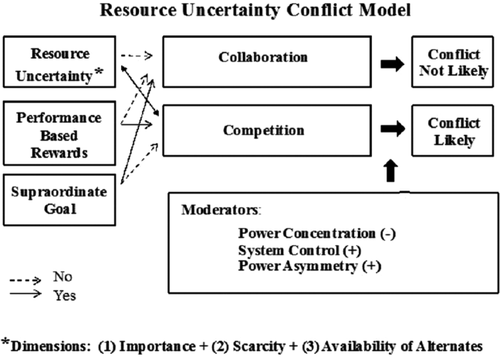

We propose that the understanding of group conflict expressed by RGCT can be informed by elements within RDT, and present Resource Uncertainly Conflict Theory (RUCT) as a plausible synthesis of the two views. Specifically, our model specifies the conditions under which group interaction will lead to competitive or collaborative behavior and thus the intensity of conflict experienced by the groups. The antecedents are resource uncertainty, performance-based rewards, and a supraordinate goal, with the first two antecedents adopted from RGCT and resource uncertainly comprised of three dimensions informed RDT as salient to groups and not conceptually misaligned with RGCT. Our model links resource uncertainty with competition via bidirectional arrows; we propose that uncertainly over environmental resources increases the risk of competition rather than cooperation, which is then more likely to lead to conflict and consequently further heighten uncertainty over a now openly disputed resource. Competition is our proposed mediator, which is posited to lead to conflict, moderated by the degree of power asymmetry, power concentration and outside system control, three structural variables impacting on conflict according to the RDT perspective. Thus, our antecedent elements encompass the outside environment, while the mediator and moderator relate more specifically to social interdependence with regard to environmental resources.

Figure 1 indicates that when resources are uncertain, groups are rewarded based on performance, and there is not a supraordinate goal, the result will be intergroup competition and the potential emergence of conflict. Figure 1 also shows that when resources are not uncertain, groups are not rewarded based on performance, and there is a supraordinate goal in place, the result will be intergroup collaboration and an absence of conflict. Thus, intergroup competition and collaboration are determined in part by these three crucial environmental factors.

Resource uncertainty conflict model. *Dimensions: (1) Importance + (2) Scarcity + (3) Availability of alternates

Another contribution of the model is the moderator of intergroup conflict. The theoretical impetus for the moderator comes from a synthesis of RDT, Emerson's (1962) theory of social conflict, and RGCT. Specifically, we propose that the greater the degree to which social groups are mutually bound within a social environment, the more competition between the groups will intensify, thereby increasing the likelihood that conflict will emerge. Our definition of conflict as a two-pronged process also represents a theoretical contribution, as we explicitly recognize an affirmative behavioral response (pushback) as a necessary component of conflict. In other words, in the context of a collective, if a disagreement with an outside group exists in the minds of its members but does not manifest in any change in behavior (i.e., a shift in strategy such as finding a new partner, formally protesting or complaining, merging or dissolving, etc.) the disagreement is socially invisible and not a demonstrable conflict.

Taken together, our proposed RUCM model integrates the micro, meso, and macro theoretical perspectives of conflict into a more comprehensive and informative overall theory for understanding why and how groups adopt cooperative and/or competitive stances toward one another in the face of resource uncertainty. While the research propositions set forth below are expressed in terms of competing groups under a shared organizational umbrella (i.e., the context is explicitly intraorganizational), we do not intend to limit the future application of RUCM to the organizational context.

6 RESOURCE IMPORTANCE

Proposition 1. Under conditions of resource importance, performance-based rewards, and no supraordinate goal, interdependent groups are more likely to compete rather than cooperate, thereby leading to conflict.

7 RESOURCE SCARCITY

Proposition 2. Under conditions of resource scarcity, performance-based rewards, and no supraordinate goal, interdependent groups are more likely to compete rather than cooperate, thereby leading to conflict.

8 AVAILABILITY OF ALTERNATES

Proposition 3. Under conditions of a lack of available alternatives, performance-based rewards, and no supraordinate goal, interdependent groups are more likely to compete rather than cooperate, thereby leading to conflict.

9 CONCENTRATION

Proposition 4. Under conditions of high power concentration, conflict will be lessened between competitive interdependent groups.

10 POWER ASYMMETRY

Proposition 5. Under conditions of high power asymmetry, conflict will be increased between competitive interdependent groups.

11 SYSTEM CONTROL

Proposition 6. Under conditions of high system control over environmental resources, conflict will be increased between competitive interdependent groups.

12 IMPLICATIONS FOR THEORY AND PRACTICE

The proposed model has several implications for future theory and practice. First, in terms of its implications for scholarship, it provides a more comprehensive perspective for understanding and predicting intergroup conflict. The model identifies three dimensions of resource uncertainty as antecedents of conflict that are not accounted for by current micro and meso theories. This is an important contribution because it connects what we already know about interfirm relationships to areas of intrafirm relations that prior research has not yet examined. Thus, the proposed model represents the synthesis of the micro, meso, and macro theories of intergroup conflict and creates the foundation for a more informed view of the multilevel factors leading to intergroup conflict.

Our proposed RUCM model is a key contribution because it synthesizes existing theories from multiple domains and levels of structural analysis and seeks to integrate them into a more usable and inclusive conceptual framework for use in future research. Theoretically, our model serves as a bridge aimed at assimilating and organizing currently disjointed and fragmented perspectives on the same topic into a more cohesive and useful model. Our approach undertakes to link seemingly unconnected theories that we believe complement rather than contradict one another, focusing on shared aspects of commonality. Taken together, our proposed model could provide a more complete understanding of interorganizational conflict than any one perspective alone, and potentially identifies new paths for research in this domain.

There are several other ways that the model proposed here could be extended to include and potentially explains phenomena outside of organizational conflict. One natural extension of the model is to the literature on social movements. For instance, many existing theories on social movements are concerned with examining the structural conditions that predicate social unrest and revolution. Just as the model explained here integrates theories relating to group conflict within organizations at multiple levels, it could also be potentially useful to apply the same integrative logic to theories that describe the process by which collective action is ignited. It is likely that forces at multiple levels (i.e., micro, meso, and macro) act on groups with any type of social or political agenda as well. Thus, there is nothing inherent to organizations that would present a likely or substantial difference enough to alter the explanation of intergroup behavior proposed here.

Another potential extension of the model is to the realm of cyberculture. As the Internet and social media continue to revolutionize the way we communicate in all spheres of life and disrupt incumbent businesses and governmental structures alike (e.g., the Arab Spring movement of 2010/2011), it is imperative to better grasp the conditions under which conflict arises, spreads, and dissipates on digital platforms. While the Internet allows for individuals to communicate and form groups more quickly and informally than has been possible in prior generations, we remain bound to the same biological imperatives and sociocultural influences. Thus, our proposed integrative model of conflict may provide a useful mechanism to approach the phenomenon, including such areas as cyberbullying, the weaponization of information (i.e., “fake news”), hate speech, and cyber protests.

In terms of its implications for practice, the proposed model addresses when and why organizational conflict is likely to emerge. As previously discussed, conflict is ever-present in the competitive business landscape, but managing its potential harmful consequences is a vital task for firm performance and survival over time. In today's fast-paced globalized environment, a deeper understanding of conflict is especially critical. Thus, having a more complete understanding of the factors that prompt conflict, both within an organization and among its external constituents, may provide a useful mechanism to reduce the threat of harmful behavioral responses to conflict and mitigate the damaging effects of a conflict outbreak when it does emerge, which the human experience suggests is an inevitable reality.

13 CONCLUSION

Given that in-group and out-group distinctions among intraorganizational groups exist, the resources available to them are finite, and firm units invariably compete over the resources they depend on, tension, hostility, and conflict between groups is sometimes inevitable. However, at the same time, organizations are also dependent upon the collaboration and cooperation of participants across groups to ensure the efficiency of day-to-day functions. Thus, employees, managers, and executives must learn how to manage the ever-present potential for conflict that exists within their boundaries and find ways to deal with it when it arises. Further, within the management literature, scholarship on conflict could benefit from taking an integrative approach to the micro and macro perspectives. Specifically, utilizing an approach, such as the one proposed here, that includes both views would place more emphasis on the numerous environmental factors that influence the emergence of intergroup conflict, while still attending to considerations of prejudice and bias that shape individual behavior.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.