Self-affirmation and goal difficulty as moderators of the question-behavior effect

Abstract

The question-behavior effect suggests that asking people questions about their behavior influences future behavior. We investigated the moderating roles of self-affirmation (Studies 1–3) and goal difficulty (Study 3). Participants completed questionnaires that included one/no-prediction question about fruit and vegetable consumption. Some participants completed a self-affirmation task as part of their questionnaire and all participants received a voucher for free fruit or vegetables. Use of the voucher was the outcome measure in all three studies. Prediction questions involving a difficult/easy to achieve goal resulted in a decrease/increase in voucher use, respectively, while adding a self-affirmation task attenuated question-behavior effects. We conclude that framing behaviors as “easy to achieve” increases the effectiveness of question-behavior effect interventions and that self-affirmation is effective in avoiding unwanted question-behavior effects.

1 INTRODUCTION

Asking people questions about their behavior can influence future behavior, the so-called question-behavior effect (QBE, Sprott et al., 2006). While this effect has been demonstrated in a wide variety of health behaviors such as blood donation (Godin, Germain, Conner, Delage, & Sheeran, 2014), healthy eating (Wood, Conner, Sandberg, Godin, & Sheeran, 2014), and health check attendance (Conner, Godin, Norman, & Sheeran, 2011), it is unclear what causes this effect to occur and which factors moderate it.

Cognitive dissonance has been proposed as a possible underlying mechanism of the QBE (Greenwald, Carnot, & Beach, 1987; Spangenberg et al., 2012; Spangenberg, Sprott, Grohmann, & Smith, 2003). Cognitive dissonance suggests that people make a prediction about their future behavior based on personal preferences or environmental factors and usually under or overestimate their actual behavior. Participants resolve the resulting dissonance by changing their behavior in line with their prediction. Recent meta-analytic attempts to untangle the underlying mechanisms of the QBE did not find clear evidence for cognitive dissonance as underlying mechanism (Wood et al., 2016) and suggest further research is needed to understand how the QBE works and which behaviors are most likely to be influenced, suggesting that undesirable and desirable behaviors are affected differently (Wilding et al., 2016).

If cognitive dissonance-related processes underlie the QBE, adding a task designed to reduce dissonance, such as self-affirmation, should attenuate the effect of asking the predicting question. Self-affirmation is the process of reducing dissonance by casting the “self” in a positive light through affirming an important aspect of the self-concept (Steele & Liu, 1983). In addition, self-affirmation can reduce defensive responding by affirming personal values (Griffin & Harris, 2011).

Self-affirmation has been used in interventions designed to influence health behaviors such as increasing sunscreen use (Jessop, Simmonds, & Sparks, 2009), reducing alcohol consumption among female adolescents (Ferrer, Shmueli, Bergman, Harris, & Klein, 2011), and stimulating fruit and vegetable consumption (Epton & Harris, 2008). However, in these cases self-affirmation is used in order to either reduce defensive responding, or to boost self-efficacy and goal setting, but not to attenuate behavior change attempts.

So far, only one study on the link between self-affirmation and the QBE has been conducted (Spangenberg et al., 2003). They found that asking a QBE question increased the percentage of people completing a cancer society survey from 30.6% to 52.0%. When adding a self-affirmation task to the questionnaire after the QBE question, this reduced the percentage of people completing the survey to 18.2%. While this result is promising in showing the possibility of cognitive dissonance as underlying mechanism, there are several reasons why conducting more research on the link between self-affirmation and QBE is important.

Spangenberg and colleagues asked participants to write an essay about why their most important trait was important to them (self-affirmation condition), or why their ninth most important trait might be important to others (control condition). This method has been critiqued for varying “on more than one dimension from the experimental condition” (Napper, Harris, & Epton, 2009, p. 47). Since writing essays might be more error prone and result in “messy” data, using a more structured manipulation such as that devised by Napper et al. (2009) will improve the validity of the findings of a study investigating self-affirmation in relation to the QBE.

In addition, while Spangenberg and colleagues (2003) do not state how many participants were part of the initial recruitment process, they excluded participants from the study if they did not meet certain criteria regarding completing the self-affirmation task and other checks and as a result “[m]any participants did not make the cut at several of these stages” (p. 58), resulting in questions about the reliability of their findings.

Lastly, it is interesting to investigate the moderating effect of self-affirmation in QBE research regarding a different type of behavior. Spangenberg's study focused on an altruistic behavior, as the participants would not personally benefit from filling in the cancer society survey. This raises the question of whether or not adding a self-affirmation task to a prediction question that is related to personal benefits would show the same effect as exploratory moderator analysis showed that QBE effects are larger when the target behavior relates to personal rather than societal welfare (Spangenberg, Kareklas, Devezer, & Sprott, 2016).

2 SELF-HANDICAPPING AND GOAL SETTING

Previous research has shown that setting an unattainable goal can enhance self-handicapping (Greenberg, 1985). Since the goal in QBE research is, implicitly, set by the way the question is framed, participants can perceive a goal as (un)obtainable, which in turn can affect the effectiveness of the intervention. In the case of unobtainable goals, participants could convince themselves that even though they might answer a QBE question in a positive manner (i.e., predicting to perform a positive behavior), the related goal could be set so high that they cannot achieve it. Indeed, a reanalysis of the data in the Wood et al. (2016) suggests that behavior difficulty attenuates QBEs (Wilding et al., 2016). In addition, models on goal setting suggest that other factors such as task complexity, other peoples' goals, and past success influence the chance of people reaching their goal (Hollenbeck & Klein, 1987). If students think that their peers do not perform the behavior, and they perceive the behavior to be so complex that it does not easily fit in their daily habits, this could result in smaller effects.

Hypothesis 1. A QBE intervention regarding eating five-a-day will show increased use of a voucher to collect free fruit or vegetables compared to a control group that does not receive a QBE intervention.

Hypothesis 2. Any QBE intervention effects will be attenuated by adding a self-affirmation task.

3 STUDY 1

3.1 Participants

Participants were undergraduate students (year 1 through 3) in a large public university in the south west of the United Kingdom. The researcher visited lectures on prearranged dates and times to invite students to take part in the study by completing a questionnaire that would then be handed out to the students who were willing to participate. Students were told that the questionnaire was about their behavior and that all their responses would be recorded anonymously. They had the right to opt-out of taking part or to withdraw from the study at any given time. Participants who did not return their questionnaire were excluded from the study, as there was no way of gauging whether the participants had completed the questionnaire or not. Any blank questionnaires that were returned without the voucher attached were added to the control condition, as no experimental task was completed.1 In total, 144 students took part in this study, 52 males, 87 females, and 5 unknown, Mage = 19.79, SD = 2.76.

3.2 Materials

3.2.1 Self-affirmation task

For this study, the self-affirmation task designed by Napper and colleagues (2009) was used. This task consists of 32 statements where participants have to answer to which extent each statement is like them on a 5-point scale. In addition to the self-affirmation task, Napper and colleagues designed a control task that is very similar to this self-affirmation questionnaire. In the control task, the same 32 questions are asked, but this time the participants have to answer the questions as if they are rating a celebrity that most, if not all, participants will have heard of. In the present study, participants rated the celebrity Kim Kardashian. As suggested by Napper and colleagues, participants who rated the celebrity were also asked an additional question about how much they liked her on a 7-point Likert scale, which was added at the end of the self-affirmation task as a manipulation check to investigate whether she was a relatively neutral choice of celebrity. In all three studies, the celebrity was rated neutral, see Table 1 for an overview of the ratings.

| Study | Mode | Median | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | 4 | 4 | 3.89 | 1.82 |

| Study 2 | 4 | 4 | 3.80 | 1.70 |

| Study 3 | 4 | 4 | 3.52 | 1.62 |

3.2.2 Free fruit or vegetables voucher

A voucher that could be redeemed for free vegetables or fruit was added at the end of the questionnaire. This voucher contained the logo of the fruit and vegetable stand in the main thoroughfare of the campus, the date, the information that participants could redeem the voucher for a free bowl of fruit or vegetables at this location on the same day and a unique code. This code was printed on each voucher with another, matched, unique code printed on the questionnaire so the redeemed vouchers could be linked to the completed questionnaires and conditions. Examples of the contents of the bowls mentioned on the voucher are five apples, four oranges, or three peppers and normally one bowl would cost £1. Redemption of the voucher (yes/no) was the behavioral variable that formed the objective behavioral outcome measure for all three studies.

3.3 Procedure

Study 1 used three-group (Control, QBE, QBE plus self-affirmation) between-subjects design, with a fourth “attitude check” condition. The attitude check condition was added separately to gauge the attitudes of participants toward eating fruit and vegetables and whether they felt able to eat fruit and vegetables on a regular basis. This attitude check is added as a separate group as (a) conducting a pilot study using a different sample would not necessarily reveal the attitudes of the participants in the current study, an issue that is resolved by randomly assigning participants to either one of the three experimental groups, or the attitude check, and (b) as attitude questions can also be used as QBE intervention (e.g., Dholakia & Morwitz, 2002), any attitude-related question could potentially affect the QBE findings beyond the QBE intervention effects we are interested in.

Participants were assigned randomly to one of the three experimental conditions or the attitude check group, by providing them with a survey from a randomized pile of questionnaires. The participants in the two QBE conditions read a short informative text about eating five-a-day and were given some examples regarding portion size. This text was followed by a prediction question that read “Do you predict that you will eat enough portions of fruit and vegetables this week to reach your 5-a-day?” with answering possibilities “yes” and “no.” After the prediction question, both prediction conditions received a self-affirmation questionnaire. Participants in the QBE condition received the questionnaire regarding Kim Kardashian, while participants in the QBE plus self-affirmation condition were asked to rate the statements about themselves instead. Participants in the control group answered unrelated filler questions that related to campus behavior of other students, before completing the control version of the self-affirmation task. Participants in the attitude check condition completed nine questions to investigate students' opinions about eating five-a-day. On the last page of the questionnaire, all participants found a voucher for a free bowl of fruit or vegetables as a reward for completing the survey. They were asked to remove the voucher from the questionnaire and hand in the questionnaire while keeping the voucher. The number of vouchers redeemed at the fruit and vegetable stand before the end of the day in each condition served as dependent variable. All three studies received ethical approval from the Faculty Research Ethics Committee.

3.4 Analysis strategy

For the attitude measurements, the means and standard deviations per item were calculated. In addition, the internal consistency was investigated through Cronbach's alpha. A randomization check was performed to investigate whether the number of participants predicting they would eat five-a-day was similar in the QBE and QBE plus self-affirmation conditions. Stepwise logistic regressions on (a) condition and (b) condition, age and gender were conducted to investigate whether the measured demographics affected the significance levels of condition across the three studies. No changes in significance levels were found. As all studies suffered from participants not completing the demographics questions, chi-square tests were conducted to investigate the condition effects on voucher use. This way, all participants who completed the other measures, but not the demographics questions, could be included in the analysis.

To investigate QBE and self-affirmation effects, an overall chi-square test and preplanned pairwise comparisons between all possible combinations of the three conditions were conducted.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Attitude measurements

The 37 participants in the attitude condition answered nine questions related to their views about eating fruit and vegetables on a 7-point Likert scale. Overall, participants were positive about eating fruit and vegetables, stating that they like the taste of fruit and/or vegetables (M = 5.98, SD = 1.38), agreeing that eating those products is pleasant (M = 5.65, SD = 1.21), and healthy (M = 6.27, SD = 1.12). In addition, they agree that it is important to eat enough fruit and vegetables (M = 5.97, SD = 1.24) and that they eat fruit and vegetables to stay healthy (M = 5.16, SD = 1.88). Students also reported that they were able to eat fruit and vegetables, given the relatively high scores on items “Eating enough fruit and vegetables fits into my eating habits” (M = 5.14, SD = 1.44) and “Fruit and vegetables are easy to prepare” (M = 5.49, SD = 1.39). Regarding costs, the participants slightly agreed with “Eating enough fruit and vegetables costs a lot of money” (M = 4.43, SD = 1.89) and “I don't eat enough fruit and vegetables when I'm low on money” (M = 4.41, SD = 2.13). The scale had an acceptable reliability (α = 0.82).

4.2 Randomization check

Across the two QBE conditions (QBE and QBE plus self-affirmation), 41.3% of the participants (31/75) predicted they would eat five-a-day in the future. The number of participants saying they would do so did not differ significantly across the two prediction conditions, χ2(1) = 2.07, p = .15.

4.3 QBE findings

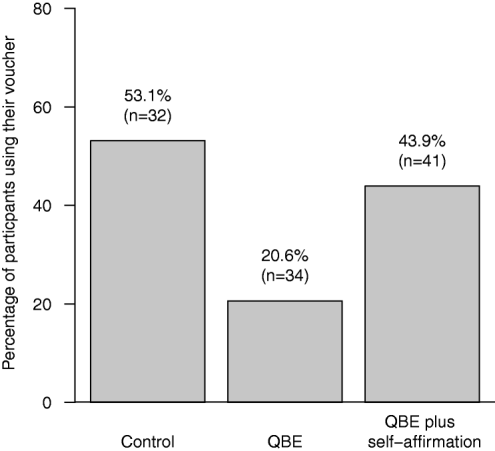

A chi-square test on number of used vouchers showed a significant effect of condition on number of vouchers used, χ2(2) = 7.92, p = .02. Pairwise comparisons show a significant reduction in voucher use in the QBE condition compared to the control group, χ2(1) = 7.54, p < .01, RR = 0.39, 95% CI [0.19, 0.81], the opposite of what was hypothesized (Hypothesis 1), namely that asking the prediction question would increase voucher use. In addition, there was a significant increase in voucher use in the QBE plus self-affirmation condition compared to the QBE condition, χ2(1) = 4.55, p = .03, RR = 2.13, 95% CI [1.01, 4.49], and no significant difference between the control and QBE plus self-affirmation conditions, χ2(1) = 0.61, p = .43, RR = 0.82, 95% CI [0.51, 1.33]. This supports the hypothesis (Hypothesis 2), that adding self-affirmation to the prediction question would attenuate the QBE (see Figure 1).

Voucher use Study 1 per condition in percentages

While the finding that participants who were asked to predict whether they would eat five-a-day were less likely to use a voucher for free fruit or vegetables is unexpected, it is in line with how the participants answered the prediction question. The majority of participants predicted that they would not eat five-a-day in the future. This supports a methodological explanation of the findings. The difference in percentage of participants answering “yes” to the prediction question did not significantly differ between the two prediction conditions. However, the percentage of participants in the QBE plus self-affirmation condition predicting they would eat five-a-day was 48.8%, while 32.4% of the participants in the QBE condition predicted they would eat five-a-day. Since the prediction question came before the self-affirmation task, the responses to the predictions should be roughly the same. The question is whether this (nonsignificant) difference has caused a negative effect of asking to predict eating five-a-day on voucher use, rather than the QBE intervention simply not affecting voucher use.

4.4 Self-affirmation as attenuating factor

The effect of self-affirmation on voucher use is interesting. Instead of reducing the likelihood of performing a behavior, as was the case in the study by Spangenberg and colleagues (2003), the negative effect of the question-behavior intervention is attenuated by an increase in voucher use in the present study, bringing the percentage of participants redeeming their vouchers back to the level of the control condition when self-affirming after being asked the five-a-day prediction question. One explanation might be that as the percentages of participants stating they would eat five-a-day were low, the self-affirmation task might have increased participants' belief that they can reach the five-a-day goal, thereby increasing the chance that participants would use the voucher. If this is the case, adding a self-affirmation task to the questionnaire before asking participants to make a prediction might result in an increase of participants stating they will eat five-a-day and subsequently increase the number of vouchers that are redeemed. Replicating the negative effect of a QBE intervention and investigating the effect of adding self-affirmation before the prediction question are the focus of Study 2.

5 STUDY 2

Study 2 served to rule out the possible alternative explanation of the findings in Study 1 that the nonsignificant difference in participants answering yes between the two experimental conditions caused the lower voucher use. Since the procedure in both conditions was similar until after the participants had made their prediction, more similar percentages of participants predicting they would eat five-a-day were expected. To rule out this difference between the experimental conditions as cause of the reduced number of vouchers used in the prediction-only condition, the present study is designed as a replication of Study 1.

Hypothesis 3. The QBE intervention regarding eating five-a-day will result in fewer redeemed vouchers compared to the control group.

Hypothesis 4. QBE intervention effects will be attenuated by adding a self-affirmation task.

Hypothesis 5. The condition that completes the self-affirmation task before the QBE intervention will show a higher percentage of participants predicting to eat five-a-day and redeeming their voucher compared to the no-prediction condition.

6 METHOD

6.1 Participants

In total, 138 students took part in this study, 49 males, 70 females, and 19 unknown, Mage = 20.87, SD = 1.84. Participants completed the study in a classroom setting.

6.2 Procedure

Study 2 used a four-group (Control, QBE, QBE plus self-affirmation, Self-affirmation plus QBE) between-subjects design with random allocation of participants to conditions. The procedure was similar to Study 1 with the addition of a self-affirmation plus QBE condition in which the self-affirmation task came before the QBE task with the five-a-day information and prediction question. To reduce the likelihood of participants in this condition realizing that the voucher was related to the QBE question, a short filler task was added after the QBE question. This task, where participants had to circle all occurrences of a specific digit in a number matrix, was added to the start of the other conditions to ensure all participants received the same number of tasks.

6.3 Analysis strategy

The analysis strategy was similar to Study 1 with an initial analysis to investigate differences in five-a-day answers in the three prediction conditions, and an overall chi-square test and preplanned comparisons to investigate the QBE and self-affirmation effects on voucher use. These preplanned comparisons consisted of all possible pair-wise comparisons between the three conditions similar to Study 1 and an added comparison of the self-affirmation plus QBE condition and QBE condition plus self-affirmation condition.

7 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

7.1 Question-behavior effects

In the three prediction conditions, 41.5% of the participants (39/94) who answered the prediction question, predicted they would eat five-a-day in the future. The number of participants saying they would do so did not differ significantly across the three prediction conditions, χ2(2) = 0.18, p = .92. The hypothesis (Hypothesis 5) that adding self-affirmation before the prediction question would lead to more participants predicting they would eat five-a-day is therefore not supported.

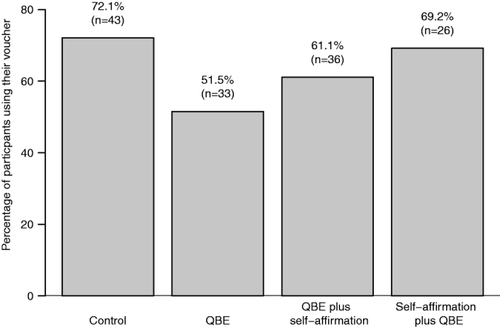

There was no significant effect of condition on number of vouchers used, χ2(3) = 3.88, p = .28. While the percentage of participants using their voucher was lower in the QBE condition compared to the control condition as hypothesized (Hypothesis 3, 51.5% vs. 72.1%), this effect was only marginally significant, χ2(1) = 3.40, p = .07, RR = 0.71, 95% CI [0.49, 1.04]. Hypothesis 4 was not supported as no significant differences were found between the QBE and QBE plus self-affirmation conditions, χ2(1) = 0.65, p = .42, RR = 1.19, 95% CI [0.78, 1.81], and the control and QBE plus self-affirmation conditions, χ2(1) = 1.07, p = .30, RR = 0.85, 95% CI [0.62, 1.17]. Even though the effects were only marginally significant (prediction-only compared to control) and nonsignificant (prediction plus self-affirmation compared to prediction-only), the directions of the effects are similar to those of Study 1 (lower voucher uptake in the prediction-only condition compared to the control condition and an attenuated effect when adding self-affirmation to the prediction question).

The hypothesis that adding self-affirmation before the prediction question could positively influence the behavioral effects of the intervention (Hypothesis 5) was not supported. The chi-square test on voucher use for the two self-affirmation conditions was not significant, χ2(1) = 0.44, p = .51, RR = 1.13, 95% CI [0.79, 1.63]. The percentages of vouchers used in each condition can be found in Figure 2.

Voucher use Study 2 per condition in percentages

While the direction of the effects is similar to the findings of Study 1, no significant difference between the conditions was found. Compared to Study 1, where the QBE intervention resulted in a 61% drop in voucher use compared to the control group, the difference was smaller in this study, with a drop in voucher use of 29% when comparing the QBE condition to the control condition. In addition, the percentages of participants predicting to eat five-a-day were more similar across conditions compared to Study 1, with percentages ranging from 38.9% to 44.0%. This means a difference in prediction answers as the influencing factor for the direction of the effect can be ruled out. Together with the finding that the number of participants answering “yes” to the prediction question did not differ significantly across conditions, this also indicates that putting the self-affirmation task before rather than after the prediction question does not significantly increase the number of participants predicting they will eat five-a-day or redeeming their voucher. The data show a marginally significant effect of the prediction question on voucher use compared to the no-prediction control condition. The question remains why participants who are asked to predict eating five-a-day seem less likely to use a free fruit or vegetables voucher compared to a no-prediction condition. As discussed in the introduction, goal difficulty can play a role in QBE and might have affected the QBE findings in Studies 1 and 2, as the goal of eating “five-a-day” could be perceived as unattainable.

To investigate this explanation of the findings in these two studies, a third study was designed to investigate the effects of goal difficulty and self-affirmation on QBEs. The third study, comparing an easily obtainable goal such as “eating fruit and vegetables” and the more difficult to obtain goal used in Studies 1 and 2 of “eating five-a-day” was designed to explore the influence of goal difficulty alongside self-affirmation in QBE interventions. As the aforementioned goal is vague and less demanding than the goal of Studies 1 and 2, asking participants an easy-goal prediction should lead to an increase in voucher use. Comparing these two types of goals is the focus of Study 3.

8 STUDY 3

Hypothesis 6. Easy-goal QBE intervention will result in more redeemed vouchers compared to the hard-goal QBE intervention.

Hypothesis 7. Easy-goal QBE condition effects are attenuated by adding a self-affirmation task.

9 METHODS

9.1 Participants

In total, 157 students took part in this study, 76 males, 72 females, and 9 unknown, Mage = 19.63, SD = 2.07. In line with Studies 1 and 2, the students were asked to complete a short questionnaire in a classroom setting.

9.2 Procedure

The present study used a 2 (Type of goal prediction: easy vs. hard) × 2 (Self-affirmation: yes vs. no) between-subjects design plus control group. Participants were assigned randomly to one of the five conditions. Participants in the control group completed a set of filler questions and were then presented with the self-affirmation control task. Participants in the QBE conditions received the five-a-day information and completed either an easy-goal prediction question, “Do you predict that you will eat fruit and vegetables this week?” or a hard-goal prediction question, “Do you predict that you will eat enough portions of fruit and vegetables this week to reach your 5-a-day?” which was similar to the prediction question in Studies 1 and 2. After this, half of the participants in each type of QBE question completed the self-affirmation control task in which they answered self-affirmation questions about a celebrity, while the other half completed the same self-affirmation questionnaire used in Studies 1 and 2. After completing these tasks, all participants received a voucher for fruit or vegetables, redemption of which was tracked using the method outlined previously.

9.3 Analysis strategy

The analysis strategy consisted of a manipulation check to investigate whether the easy-goal question received more positive predictions compared to the hard-goal question that was used in Studies 1 and 2. To investigate the behavior outcomes, an overall chi-square test and preplanned comparisons were conducted. These preplanned comparisons consisted of comparisons between the control and the easy-goal prediction conditions, the easy-goal and hard-goal conditions, and the easy-goal and easy-goal plus self-affirmation conditions.

10 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

10.1 Manipulation check

The manipulation check involved testing whether the participants in the easy-goal conditions were more likely to make a positive prediction (answer they would behave in line with the prediction question) compared to the participants in the hard-goal conditions. The number of participants saying “yes” was significantly higher in the easy-goal conditions compared to the hard-goal conditions, χ2(1) = 52.66, p < .001. Closer inspection showed that there were no significant differences between the easy-goal prediction-only and easy-goal self-affirmation conditions, χ2(1) = 2.67, p = .10. The same nonsignificant result was found for the hard-goal conditions, χ2(1) = 2.27, p = .13.

10.2 Question-behavior effects

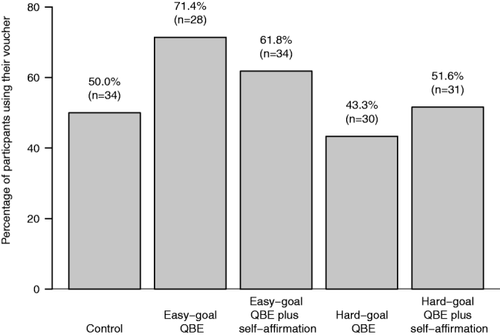

There was no significant effect of condition on number of vouchers used, χ2(4) = 5.82, p = .21. While the effects are in the hypothesized directions (see Figure 3), the overall effect is not strong enough to result in a statistically significant replication of Studies 1 and 2.

Voucher use Study 3 per condition in percentages

Closer inspection through pairwise comparisons shows a marginally significant difference between the easy-goal QBE condition and the control condition, χ2(1) = 2.93, p = .087, RR = 1.43, 95% CI [0.95, 2.15], indicating that asking an easy-goal prediction question could increase rather than decrease voucher use compared to a control group that is not asked to predict their future behavior. In addition, a significant difference between the easy-goal QBE condition and the hard-goal QBE condition was found, χ2(1) = 4.66, p = .03, RR = 1.65, 95% CI [1.03, 2.64], which supports the hypothesis that the participants in the easy-goal prediction condition are more likely to redeem their vouchers than the participants in the hard-goal prediction condition (Hypothesis 6). While the participants in the easy-goal QBE plus self-affirmation condition showed lower levels of voucher use compared to the easy-goal QBE condition (61.8% vs. 71.4%), this effect was not significant, χ2(1) = 0.64, p = .42, RR = 0.86, 95% CI [0.61, 1.23], thus Hypothesis 7 is not supported. The percentages of vouchers redeemed in each condition can be found in Figure 3.

10.3 Easy-goal versus hard-goal prediction

The easy-goal question resulted in a significant higher number of participants answering “yes” to the prediction question compared to the participants in the hard-goal prediction conditions. This difference in answers resulted in a marginally significant positive effect between the easy-goal prediction and the no-prediction control group, showing that an easier goal can influence the direction of the effect and result in a 43% increase in voucher use, rather than the reductions in voucher use found across all three studies when asking the five-a-day prediction question.

The significant positive effect of an easy-goal prediction compared to hard-goal prediction indicates that the participants in Studies 1 and 2 may have perceived that the goal of eating five-a-day was unrealistic while a trivial prediction such as eating fruit and vegetables during the week was easy to adhere to. This explanation is supported by the significant difference in responses to the prediction question in the easy-goal and hard-goal conditions, with the participants in the easy-goal conditions predicting more often they would reach the set goal. The question remains whether this effect was due to participants' intrinsic feeling that they could not reach the goal of eating five-a-day, or other factors, such as the perceptions of the behavior of peers.

11 GENERAL DISCUSSION

All three studies showed reduced voucher use after participants were asked a five-a-day prediction question compared to a control group and adding self-affirmation to a prediction question seems to attenuate QBEs as an increase in voucher use was found. This finding is in line with the study by Spangenberg and colleagues (2003) that showed that an increase in behavior after a QBE intervention can be attenuated when a self-affirmation task is added to the prediction question. Our research adds to their findings by showing that attenuated effects are not merely found when the initial behavior is increased after a prediction question, but also when a prediction question leads to a reduction in behavior as was the case in the five-a-day prediction groups.

Study 3 seems to suggest that it is the difficulty of the focal behavior that caused a drop in voucher use in the QBE condition, the opposite of what was initially hypothesized. In their meta-analytic review, Wilding et al. (2016) showed that behavioral difficulty affects QBE findings, where easier to perform behaviors are affected to a greater extent. Framing the same behavior, using the free fruit and vegetable voucher, as either part of eating five-a-day or as eating any fruit or vegetables greatly affected prediction responses and voucher use.

The moderating effect of self-affirmation suggests that dissonance processes drive the QBE. This finding does not only have implications for the underlying mechanisms of the QBE, but can also advance intervention design practices and help avoid unwanted QBE effects. For example, the finding that a difficult goal resulted in decreases in voucher use accentuates the need for pilot-testing behaviors before designing a QBE intervention, as a large-scale intervention using unobtainable goals might backfire and do more harm than good. Additionally, researchers interested in vice or illegal behaviors could use self-affirmation as a method to shield participants from experiencing negative side effects from taking part in their research.

11.1 Limitations

There are a few limitations of the findings. The first limitation is that the sample sizes were quite low, due to lower than expected attendance in the classes used the studies, which resulted in lower power, especially as some of the effects would be difficult to detect without the appropriate power levels (e.g., the 14% drop in voucher use in the easy-goal plus self-affirmation condition compared to the easy-goal prediction condition). Post hoc power tests show that for the basic QBE test (Control vs. five-a-day prediction) in all three studies, the power dropped from 79.6% in Study 1 to 7.7% in Study 3. The second limitation is that the time between the prediction question and the first possibility students had to use their voucher differed substantially within the sample. Some students were asked to fill in the questionnaire, and receive their voucher, during a one or 2 hr lecture, while a subgroup of the sample used in Study 3 received the questionnaire at the start of a 3 hr lecture. Since students would have to wait to redeem their voucher until their lecture was over, this might have influenced the results.

An indication that the time interval might influence the outcomes is found in a recent meta-analysis (Wood et al., 2016) that showed that increased time intervals reduced the effect size of QBE studies. The data in Study 3 hint at possible time effects as exploratory analysis, where the participants who took part in the study during a 3 hr lecture were removed from the sample, lead to an increased effect size. Future research comparing different time intervals experimentally is needed to determine the long-term effects of QBE interventions. This time interval could be investigated in relation to when participants are able to collect their free fruit and vegetables (i.e., lecture length) or to when participants are allowed to redeem their voucher (e.g., providing them with a voucher that is only valid on a specific day later in the week instead of on the same day).

A final limitation is that participants could not set a goal themselves, but instead were asked about specific goals (eating five-a-day or eating fruit and vegetables in the coming week). A study investigating whether asking people to predict how many days in the coming week they would reach the five-a-day goal or asking them how much fruit and vegetables they predict they would eat in the coming week might show different results.

12 CONCLUSION

The goal of this article was to investigate how self-affirmation and goal difficulty might moderate the QBE, by investigating goal difficulty and the role of self-affirmation in relation to the QBE. Three studies have shown that asking prediction questions can reduce positive behavior when the behavior is deemed too difficult. The addition of an easy-goal prediction condition in the third study showed that the same behavior increased when the goal was easier to attain. In addition, adding a self-affirmation task to a QBE intervention can attenuate the effect both when positive as well as negative effects are obtained. Further research should focus on investigating whether goal setting or the perception of the behavior of peers can account for unexpected negative effects of QBE interventions on positive behaviors.