Association of surgeon's sex, and surgeon-patient dyad with financial outcomes among patients undergoing cancer surgery

Abstract

Background and Objectives

Surgeon sex has been associated with perioperative clinical outcomes among patients undergoing oncologic surgery. There may be variations in financial outcomes relative to the surgeon-patient dyad. We sought to define the association of surgeon's sex with perioperative financial outcomes following cancer surgery.

Methods

Patients who underwent resection of lung, breast, hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB), or colorectal cancer between 2014 and 2021 were identified from the Medicare Standard Analytic Files. A generalized linear model with gamma regression was utilized to characterize the association between sex concordance and expenditures.

Results

Among 207,935 Medicare beneficiaries (breast: n = 14,753, 7.1%, lung: n = 59,644, 28.7%, HPB: n = 23,400, 11.3%, colorectal: n = 110,118, 53.0%), 87.8% (n = 182,643) and 12.2% (n = 25,292) of patients were treated by male and female surgeons, respectively. On multivariable analysis, female surgeon sex was associated with slightly reduced index expenditures (mean difference -$353, 95%CI -$580, -$126; p = 0.003). However, there were no differences in 90-day post-discharge inpatient (mean difference -$−225, 95%CI -$570, -$121; p = 0.205) and total expenditures (mean difference $133, 95%CI -$279, $545; p = 0.525).

Conclusions

There was minor risk-adjusted variation in perioperative expenditures relative to surgeon sex. To improve perioperative financial outcomes, a diverse surgical workforce with respect to patient and surgeon sex is warranted.

1 INTRODUCTION

The underrepresentation of women in surgical subspecialties represents a challenge to attain workforce diversity and perpetuates gender inequality.1, 2 Although females comprised one-half of United States (US) medical school graduates over the last decade, only 37.1% of the US physician workforce is female.3, 4 Moreover, a recent Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) report noted that, although roughly 36% of female undergraduate and medical students expressed an interest in surgical specialties, their enrollment in surgical training programs was much lower.5 The reasons for the under-representation of women include sex/gender-based discrimination in the workspace, difficulties in entering into surgical training, and inadequate role models.6-8 In turn, there is a pressing need for active efforts to enhance the representation of women in surgical settings.

Prior research has demonstrated that patients weigh various factors, including surgeon qualifications, hospital reputation, and demographic characteristics such as gender and ethnicity when choosing their healthcare provider.9 For instance, many female patients prefer to undergo surgical care by a female surgeon, and vice versa.10, 11 However, as surgery has traditionally been a male-dominated field, female patients often end up receiving care from male physicians, which may result in hesitancy and a lack of trust that can hinder care. The relationship between a healthcare provider and a patient is crucial for effective communication and clinical care that align with patient goals.10, 12, 13 A strong patient-provider relationship may lead to better patient satisfaction, adherence to medical advice, and improvement in overall well-being.14-17 The patient-provider relationship depends on several factors, including effective and timely communication, patient trust in their provider, and even the gender of the surgeon.12 Several studies have demonstrated the differential impact of physician sex on clinical outcomes.10, 18 For example, Frank et al. demonstrated that patients were referred for counseling about unhealthy behaviors more often by female versus male physicians.18 In addition, our own research group has reported that sex-concordant care may be associated with improved clinical outcomes following surgery.10 However, the extent to which these differences translate into postoperative healthcare utilization patterns and financial expenditures remains relatively unexamined. Hence, the objective of this study was to characterize the association of surgeon sex and the surgeon-patient dyad with perioperative financial outcomes following complex cancer surgery.

2 METHODS

2.1 Data source & study population

Data were obtained from 100% Medicare Standard Analytic Files provided by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.19 International Classification of Diseases, ICD-10, ICD-9, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes, and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes were utilized to identify patients who underwent surgery for lung, breast, hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB), or colorectal cancer from 2014 to 2020.10, 20, 21 The current study focused on lung, breast, HPB, or colorectal cancer as these diagnoses are the most common cancers and primary contributors to cancer-related deaths in the United States.22 Individuals were age 65 years or older and were enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B at the time of surgery; patients covered by an HMO were excluded. The need for informed patient consent was waived and the study was approved by The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board.

2.2 Study and outcome measures

Baseline variables included patient age, race/ethnicity, sex, region, Charlson comorbidity index (<2 and ≥2), type of procedure, type of admission (urgent or elective), hospital volume, metropolitan versus rural status, and county-level social vulnerability index (SVI). Data on county-level SVI were obtained from the Center for Disease Control and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.23 SVI, which is a validated measure of community resistance to external pressures, was linked using county-level Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) codes, and divided into tertiles for purpose of analyses.24 Hospital volume was also calculated and categorized as low, medium, and high based on tertiles.25 ICD-9 and 10 codes were utilized to assess comorbidities, as previously defined.26, 27 Race/ethnicity was defined as a self-reported social construct, and not a reflection of the genetic ancestry of patients, and was categorized as Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and Non-Hispanic Other race/ethnicity.28 The Non-Hispanic Other race/ethnicity group included American Indians, Alaskan Natives, Native Hawaiians, Asians, Pacific Islanders, and self-reported “Other” race/ethnicity.28 Surgeon characteristics included surgeon sex and years of practice. Patient surgeon dyads of male patient-male surgeon, and female patient-female surgeon were categorized as sex-concordant patient dyads. On the other hand, male patient-female surgeons and female patient-male surgeons were categorized as sex-discordant dyads.11, 29

The outcomes of interest were perioperative expenditures including index expenditures, 90-day total post-discharge expenditures, 90-day inpatient post-discharge expenditures, and 90-day outpatient post-discharge expenditures. All expenditure data were adjusted by wage index, indirect medical education, and disproportionate share hospitals to allow for equitable comparisons and were expressed in 2020 US dollars.

2.3 Statistical analyses

Median values with interquartile ranges (IQR) were used to represent continuous variables and frequencies with percentages were used for categorical variables. The chi-square test was used to assess categorical variables and the Wilcoxon test was used for continuous variables. A generalized linear model with gamma regression and log link was used to assess the association between surgeon sex, and surgeon-patient dyad and perioperative expenditures. Models were adjusted for patient sex (except in model without surgeon-patient dyad), race, age, CCI, SVI, type of admission (elective vs urgent), cancer type, region, rurality (Nonmetropolitan vs metropolitan), cancer type, and hospital volume. Stata version 18 was utilized to perform statistical analyses and a two-sided significance level of α = 0.05 was used.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographic characteristics

Among 207,935 Medicare beneficiaries (breast: n = 14,753, 7.1%, lung: n = 59,644, 28.7%, HPB: n = 23,400, 11.3%, colorectal: n = 110,118, 53.0%), 87.8% (n = 182,643) and 12.2% (n = 25,292) of patients were treated by male and female surgeon respectively. Overall, the median age was 71 (IQR, 66-77) and roughly one-half of patients was male (male, n = 94,655, 45.5%; female, n = 113,280 54.5%). Most patients were Non-Hispanic White (n = 180,059, 86.6%) with smaller subsets being Non-Hispanic Black (n = 16,604, 8.0%), Hispanic (n = 2,277, 1.1%) or Non-Hispanic Other race/ethnicity (n = 8,995, 4.3%). The majority of patients resided in the South (n = 86,176, 41.4%) or the Midwest region (n = 48,128, 23.1%) of the US, were treated at teaching hospitals (n = 122,783, 59.0%), and underwent an elective operation (n = 145,451, 70.0%). Overall, there were 3544 (12.0%) female and 25,983 (88.0%) male surgeons; median years (IQR, 19–36) in practice was 36 (Table 1).

| Male | Female | Total | Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Patients | 182,643 (87.8%) | 25,292 (12.2%) | 207,935 (100.0%) | |

| Age | 71 (66–77) | 71 (65–77) | 71 (66–77) | 0.003 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 84,838 (46.5%) | 9817 (38.8%) | 94,655 (45.5%) | <0.001 |

| Female | 97,805 (53.5%) | 15,475 (61.2%) | 113,280 (54.5%) | |

| CCI | ||||

| <2 | 70,301 (38.5%) | 9911 (39.2%) | 80,212 (38.6%) | 0.033 |

| ≥2 | 112,342 (61.5%) | 15,381 (60.8%) | 127,723 (61.4%) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 158,452 (86.8%) | 21,607 (85.4%) | 180,059 (86.6%) | <0.001 |

| Black | 14,473 (7.9%) | 2131 (8.4%) | 16,604 (8.0%) | |

| Hispanic | 1969 (1.1%) | 308 (1.2%) | 2277 (1.1%) | |

| Other | 7,749 (4.2%) | 1,246 (4.9%) | 8,995 (4.3%) | |

| Cancer Type | ||||

| HPB | 21,114 (11.6%) | 2286 (9.0%) | 23,400 (11.3%) | <0.001 |

| CRC | 96,032 (52.6%) | 14,086 (55.7%) | 110,118 (53.0%) | |

| Breast | 10,806 (5.9%) | 3947 (15.6%) | 14,753 (7.1%) | |

| Lung | 54,691 (29.9%) | 4973 (19.7%) | 59,664 (28.7%) | |

| Hospital Volume | ||||

| Low | 59,665 (32.7%) | 8039 (31.8%) | 67,704 (32.6%) | 0.016 |

| Moderate | 60,605 (33.2%) | 8455 (33.4%) | 69,060 (33.2%) | |

| High | 62,373 (34.2%) | 8797 (34.8%) | 71,170 (34.2%) | |

| Region | ||||

| Midwest | 41,966 (23.0%) | 6,162 (24.4%) | 48,128 (23.1%) | <0.001 |

| Northeast | 35,264 (19.3%) | 5550 (21.9%) | 40,814 (19.6%) | |

| South | 77,878 (42.6%) | 8298 (32.8%) | 86,176 (41.4%) | |

| West | 27,535 (15.1%) | 5282 (20.9%) | 32,817 (15.8%) | |

| Metropolitan Status | ||||

| Metropolitan | 141,516 (77.7%) | 20,074 (79.6%) | 161,590 (78.0%) | <0.001 |

| Nonmetropolitan | 40,539 (22.3%) | 5131 (20.4%) | 45,670 (22.0%) | |

| Hospital | ||||

| Nonteaching | 75,262 (41.2%) | 9890 (39.1%) | 85,152 (41.0%) | <0.001 |

| Teaching | 107,381 (58.8%) | 15,402 (60.9%) | 122,783 (59.0%) | |

| Type of Admission | ||||

| Elective | 128,891 (70.6%) | 16,560 (65.5%) | 145,451 (70.0%) | <0.001 |

| Urgent | 53,752 (29.4%) | 8732 (34.5%) | 62,484 (30.0%) | |

| Social Vulnerability Index | ||||

| Low | 59,561 (32.7%) | 9355 (37.1%) | 68,916 (33.3%) | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 61,422 (33.7%) | 8,437 (33.5%) | 69,859 (33.7%) | |

| High | 61,074 (33.5%) | 7412 (29.4%) | 68,486 (33.0%) | |

| Years of Experience | ||||

| 1st Quartile | 46,806 (25.7%) | 6546 (25.9%) | 53,352 (25.7%) | 0.832 |

| 2nd Quartile | 45,053 (24.7%) | 6220 (24.6%) | 51,273 (24.7%) | |

| 3rd Quartile | 49,879 (27.4%) | 6905 (27.3%) | 56,784 (27.3%) | |

| 4th Quartile | 40,633 (22.3%) | 5586 (22.1%) | 46,219 (22.3%) | |

- Note. Age was reported as median (interquartile range), Race was reported as Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and Non-Hispanic Other. Statistically significant: p < 0.05.

- Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CRC, colorectal cancer; HPB, Hepato-pancreato-biliary.

Patients treated by male surgeons were more likely to be Non-Hispanic White (86.8% vs. 85.4%), have a CCI score ≥2 (61.5% vs. 60.8%), and reside in a high SVI (33.5% vs 29.4%) counties. Among male patients, 84,838 (89.6%) patients were treated by a male surgeon, and 9817 (10.4%) were treated by a female surgeon. Among female patients, 97,807 (86.3%) were operated upon by a male surgeon, whereas 15,475 (13.7%) were treated by a female surgeon.

The median index expenditure after surgery was $16,404 (IQR, $12,103–$23,566). Median total, post-discharge inpatient, and outpatient expenditures were $8,912 ($1198–$27,207), $0 ($0–$15,723), and $2,266 ($518–$7,088), respectively (Supporting Information S1: Table S1).

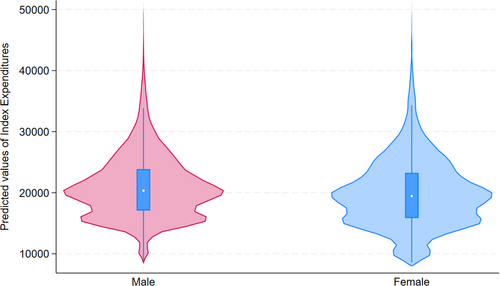

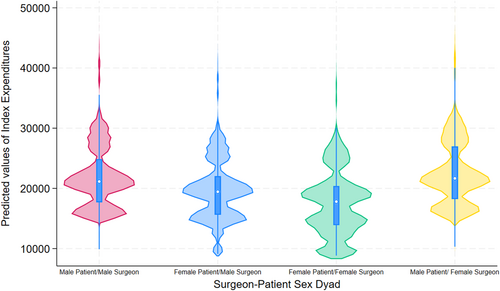

3.2 Association of surgeon sex, surgeon-patient dyad, and perioperative expenditures

Overall, median index expenditures were higher among patients treated by a male versus female surgeon ($16,462 [$12,284–$23,665] vs. $15,937 [$10,969–$23,013]; p < 0.05). In contrast, median 90-day total post-discharge expenditures ($9530 [$1362–$27,220] vs. $8,825 ($1,176–$27,206]), and 90-day outpatient expenditures ($1527 [$153–$10,038] vs. $1291 [$131–$9756]) were higher among patients treated by a female surgeon (all p < 0.001) (Figure 1). On examination of individual surgeon-patient dyads, median index expenditure was highest among male patient-female surgeon dyads followed by male patient-male surgeon dyads (Male Patient—Male Surgeon: $16,905 [$13,017–$27,155], Female Patient—Male Surgeon: $16,076 [$11,749–$21,853], Male Patient—Female Surgeon: $17,207 [$13,120–$28,976], Female Patient—Female Surgeon: $15,149 [$10,122–$20,684], p < 0.05). Moreover, total 90-day post-discharge expenditure was slightly higher for male patient-female surgeon and male patient-male surgeon dyads (Male Patient—Male Surgeon: $10,124 [$1249–$30,014], Female Patient—Male Surgeon: $7867 [$1121–$24,825], Male Patient—Female Surgeon: $11,336 [$1461–$31,568], Female Patient—Female Surgeon: $8577 [$1305—$24,586], p < 0.05) (Suppōrting Information S1: Table S2).

On multivariable analysis, after controlling for sociodemographic characteristics, female surgeon sex was associated with slightly reduced index expenditures (risk-adjusted mean difference -$353, 95%CI -$580, -$126; p = 0.003). However, there were no differences in 90-day post-discharge inpatient (risk-adjusted mean difference -$−225, 95%CI -$570, -$121; p = 0.205) and total expenditures (risk-adjusted mean difference $133, 95%CI -$279, $545; p = 0.525). Moreover, there was no difference in odds of 90-day readmission after surgery relative to surgeon sex (OR 1.00 95%CI 0.97–1.04; p = 0.827) (Table 2). On examination of surgeon-patient dyads, among male patients, the male patient-female surgeon dyad was associated with higher index expenditures (reference: Male Patient—Male Surgeon; Male Patient—Female Surgeon, risk-adjusted mean difference: $+454, 95% CI $40, $868; p = 0.030). Similarly, among female patients, a male patient-female surgeon dyad was associated with slightly higher index expenditures (reference: Female Patient—Female Surgeon; Female Patient—Male Surgeon, mean difference: $+807, 95%CI $549, $1065; p < 0.001). In contrast, there was no difference in 90-day outpatient and total expenditures after surgery among male and female patient dyads. Similarly, there were no differences in risk-adjusted odds of 90-day readmission among male and female patient dyads. (Table 3) (Figure 2).

| Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean difference/OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male surgeon | Female surgeon | (Ref: Male) | ||

| Index expenditure, $ | 20,780 (20,698–20,860) | 20,426 (20,212–20,640) | −353 (−580,−126) | 0.003 |

| Total 90-day post-discharge expenditures, $ | 20,602 (20,440–20,763) | 20,735 (20,342–21,127) | 133 (−279, 545) | 0.525 |

| Total 90-day post-discharge inpatient expenditures, $ | 13,078 (12,936– 13,221) | 12,854 (12,524–13,183) | −225 (−570,121) | 0.205 |

| Total 90-day post-discharge outpatient expenditures, $ | 7,660 (7576–7743) | 7,952 (7746–8158) | 293 (78,507) | 0.007 |

| 90-day readmissions, n (%) | 47,049 (25.9%) | 6613 (26.4%) | 1.00 (0.97–1.04) | 0.827 |

- Note. Statistically significant <0.05. OR reported for Readmission.

| Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean difference/OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male patient-male surgeon | Male patient-female surgeon | (Ref: Male patient-male surgeon) | ||

| Index expenditure, $ | 22,173 (22,041–22,305) | 22,627 (22,233–23,021) | 454 (40,868) | 0.030 |

| Total 90-day post-discharge expenditures, $ | 22,339 (22,094–22,583) | 22,801 (22,129–23,472) | 462 (−240,1164) | 0.193 |

| Total 90-day post-discharge inpatient expenditures, $ | 14,353 (14,141–14,564) | 14,489 (13,920–15,058) | 136 (−459,731) | 0.652 |

| Total 90-day post-discharge outpatient expenditures, $ | 8059 (7937–8181) | 8440 (8100–8779) | 381 (30,732) | 0.030 |

| 90-day readmissions, n (%) | 22,875 (27.2%) | 2761 (28.4%) | 1.02 (0.97–1.07) | 0.469 |

| Female patient-female surgeon | Female patient-male surgeon | (Ref: Female patient-female surgeon) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index expenditure, $ | 18,750 (18,509–18,990) | 19,557 (19,457–19,657) | 807 (549,1065) | <0.001 |

| Total 90-day post-discharge expenditures, $ | 19,106 (18,633–19,579) | 19,140 (18,924–19,355) | 34 (−464,532) | 0.894 |

| Total 90-day post-discharge inpatient expenditures, $ | 11,602 (11,206–11,998) | 11,990 (11,797–12,183) | 388 (−27,804) | 0.070 |

| Total 90-day post-discharge outpatient expenditures, $ | 7543 (7287–7800) | 7332 (7217–7448) | −211 (−479,57) | 0.119 |

| 90-day readmissions, n (%) | 24,174(24.9%) | 3852 (25.1%) | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) | 0.953 |

- Note. Statistically significant <0.05. OR reported for Readmission.

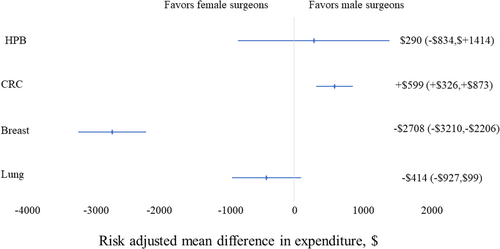

On stratified analysis by race/ethnicity, among White patients, female surgeon sex was associated with slightly reduced index expenditures (risk-adjusted mean difference -$392, 95%CI -$628, -$158; p = 0.001). However, among Black, Hispanic, and other races/ethnicities, surgeon sex had no association with index or post-discharge expenditures. On stratified analysis according to type of procedure, female surgeon sex was associated with reduced index expenditure (risk-adjusted mean difference -$2,708, 95%CI -$3,210, -$2,206; p = 0.001) and 90-day total post-discharge expenditures (risk-adjusted mean difference -$1,199, 95%CI -$2,377, -$21; p = 0.001) after breast surgery. In contrast, female sex was associated with slightly higher index expenditures after colorectal surgery (Supporting Information S1: Table S3) (Figure 3).

4 DISCUSSION

Multiple factors play a role in determining health outcomes after a surgical procedure. Among these, a surgeon's sex and sex-concordant provider-patient dyads have been associated with clinical outcomes.10, 11, 30 Sex-concordant care may positively influence both provider and patient attitudes and actions during clinical interactions leading to a reduction in explicit and implicit biases. Furthermore, sex-concordance encourages patient involvement in care, resulting in better communication, and a patient-centric care process.11-13 Nonetheless, the extent to which sex concordant patient-provider dyads translate into differences in perioperative healthcare utilization patterns and financial expenditures remains ill-defined. Importantly, increased cost burden after surgery may put already disadvantaged patients at risk of missing crucial health services.31-33 The current study was important because we specifically characterized the relationship between surgeon sex and provider-patient dyad on perioperative financial outcomes among patients undergoing surgery for breast, lung, HPB, or colorectal cancer. Interestingly, male surgeons more often treated individuals residing in high social vulnerability, as well as patients with multiple comorbidities. However, there were several variations relative to surgeon sex and perioperative expenditures. While there were no differences in 90-day post-discharge inpatient (mean difference -$−225, 95%CI -$570, -$121; p = 0.205) and total expenditures (mean difference $133, 95%CI -$279, $545; p = 0.525), female surgeon sex was associated with slightly reduced index expenditures (mean difference -$353, 95%CI -$580, -$126; p = 0.003).

Prior research has demonstrated provider-patient sex concordance to be associated with an improved provider−patient relationship and better perioperative clinical outcomes.10, 11, 29, 34 Wallis et al. reported that sex discordant dyads and male surgeons were associated with worse clinical outcomes including mortality, complications, reoperation, and readmission after surgery among patients undergoing elective general surgery procedures.11 Similarly, recent work by our own group demonstrated that sex discordance was more likely to be associated with reduced odds of achieving an “optimal” postoperative outcome among patients undergoing cancer surgery.10 Other studies have noted that a sex concordant provider−patient relationship led to improved patient rapport, whereas a sex discordant provider−patient relationship was associated with a greater diagnostic uncertainty.35 While our results indicate a variation in practice patterns between male and female physicians, there is a scarcity of studies that have examined the link between provider-patient sex concordance (or discordance) and healthcare costs. Wallis et al. did report lower 30-day, 90-day, and 1-year healthcare costs for female surgeons among patients undergoing elective general surgery procedures.36 Similarly, in the current study, we noted that surgeon sex and sex concordance was associated with variations in financial expenditures. Of note, sex discordant provider−patient dyads were associated with slightly higher risk-adjusted index and 90-day post-discharge among Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. Moreover, patients treated by female surgeons had slightly reduced financial expenditures compared with male surgeons.

While healthcare expenses based on the surgeon gender may vary, the root cause remains ill-defined. Subset analyses demonstrated that the greatest variation in cost expenditures among patients treated by female and male surgeons related to inpatient and post-discharge ongoing care expenses. Several factors may contribute to these cost discrepancies, such as differences in preoperative and perioperative practices, surgical decision-making processes, and the utilization of intraoperative equipment or technologies.36 Prior data have noted an elevated incidence of adverse postoperative outcomes among patients treated by male surgeons. Patients often prefer sex concordant surgeons for sensitive examinations as sex discordance between surgeon and patient may be associated with incomplete examinations in the postoperative setting.10 All of these factors might result in a failure to detect early perioperative complications in patients who have deviations from an ideal postoperative pathway. Managing these complications may potentially add to additional inpatient costs due to greater healthcare requirements and extended inpatient stays. Moreover, other studies have demonstrated differing practice patterns among female and male healthcare providers, with women exhibiting higher levels of guideline adherence, patient-focused care, and transparent communication patterns.18, 37-40 There is a need for more in-depth qualitative studies among surgeons to gain a deeper understanding of their decision-making processes, practice methods, and post-discharge care plans that may influence patient recovery and associated healthcare costs after surgery.

Despite advancements in surgical care, racial and ethnic disparities persist among patients undergoing complex cancer surgery, leading to variations in healthcare utilization, particularly among African American and Hispanic patients who exhibit greater post-surgery healthcare utilization. The relationship between patient race/ethnicity and financial outcomes relative to surgeon sex may be important. In the current study, stratified analysis among female surgeons revealed minimal differences in financial expenditures across all racial/ethnic groups, highlighting the comparable outcomes among patients of all backgrounds. Increasing the representation of female surgeons in surgery is essential to address gender disparities and ensure sex-concordant oncological care for all patients, especially females. Notably, among the 207,935 patients undergoing oncological surgery, only 25,292 (12.2%) had a female surgeon. Although women currently comprise one-third of the US physician workforce, and one-half of medical school graduates, there is marked underrepresentation of females in the surgical field. Recently, the Association of American Medical Colleges has undertaken a multi-level initiative to eliminate gender-based disparities in healthcare by boosting female representation across all medical fields. To achieve this, comprehensive evaluation processes and ongoing mentoring schemes are necessary to enhance the presence of women among surgical training programs. Moreover, prioritizing recruitment and advancement of female faculty members is crucial for promoting inclusivity within the surgical field. Similar initiatives are needed to improve the delivery of equitable and holistic cancer care and bridge disparities by enabling increased representation and opportunities for sex-concordant care in oncological surgery.

The results of the current study should be interpreted while considering the following limitations. In addition to a surgeon gender, several other hospital-, patient- and provider-level factors may play a role in patient care and impact perioperative healthcare utilization and financial expenditures. The current work did utilize available variables in the Medicare database to account for potential confounders. As Medicare only included patients above 65 or patients below 65 with a disability, the results of our study may not be generalizable to younger patients or individuals with private insurance. Data miscoding and misclassification errors may also have led to inaccuracies in the use of administrative records. For this reason, ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM diagnostic codes that have been previously validated were utilized; these codes have demonstrated high fidelity with the medical record.41

In conclusion, female surgeon sex and sex-concordant dyads were associated with slightly reduced financial expenditures after surgery among patients with cancer. Male surgeons were more likely to care for sicker, and more vulnerable patient populations compared with female surgeons. These data stress the need to support women surgeons for a more diverse workforce and better patient care. Understanding the factors behind sex-based outcome differences is crucial for improving inclusivity and delivering high-quality surgical care to all patients.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data for this study were obtained from the Medicare Standard Analytic Files. There are restrictions to the availability of this data, which is used under license for this study. Data can be accessed with permission from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

REFERENCES

5 SYNOPSIS OF TABLE OF CONTENTS

Surgeon sex and surgeon-patient sex concordance have been associated with perioperative clinical outcomes among patients undergoing oncologic surgery. In the current study, there was a risk adjusted variation in perioperative expenditures relative to surgeon sex. To improve perioperative outcomes, a diverse surgical workforce with respect to patient and surgeon sex is warranted.