Propensity-score matched analysis of the pathologic outcomes and survival benefits of neoadjuvant therapy in stage II–III anal adenocarcinoma

Abstract

Background

Anal adenocarcinomas are a rare condition which account for less than 10% of anal cancers. The present study aimed to assess the impact of neoadjuvant therapy on the clinical and pathologic outcomes and overall survival (OS) of patients with stage II–III anal adenocarcinomas after abdominoperineal resection (APR).

Methods

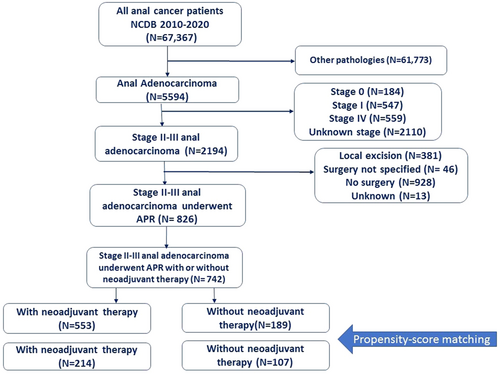

A retrospective cohort study of patients with anal adenocarcinoma in the US National Cancer Database (NCDB) (2010–2020) was conducted. Propensity-score matching was used to compare patients who received neoadjuvant therapy (neoadjuvant therapy group) to the no-neoadjuvant group. The primary outcome was 5-year OS whereas secondary outcomes included conversion to open surgery, hospital stay, surgical margins, 30-day mortality, 90-day mortality, and 30-day readmission.

Results

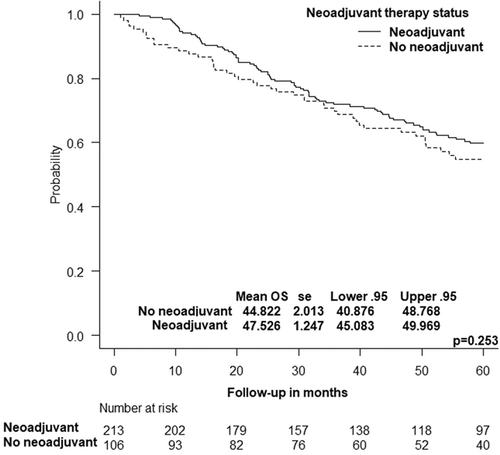

A total of 742 patients (56% male) with a mean age of 63.6 ± 12.4 years were included. A total of 214 patients in the neoadjuvant group were matched with 107 in the no-neoadjuvant group. The mean OS was similar between the two groups (47.5 vs. 44.8 months, p = 0.253). Patients who received neoadjuvant therapy had a longer median time between diagnosis and surgery (151 vs. 54 days, p < 0.001), lower 90-day mortality (1.9% vs. 6.7%, p = 0.046), more pT0 tumors (15.7% vs. 0%), less pT3-4 tumors (28.4% vs. 36.4%, p = 0.001), less pN1-2 tumors (22.9% vs. 34.7%, p < 0.001), and less lymphovascular invasion (16.2% vs. 40%, p < 0.001) than the no-neoadjuvant group. Both groups had similar conversion rates, hospital stay, 30-day mortality, 30-day readmission, and positive surgical margins.

Conclusions

Neoadjuvant therapy before APR was associated with significant downstaging of anal adenocarcinomas and lower 90-day mortality, yet similar OS to patients who were surgically treated without neoadjuvant treatment.

1 INTRODUCTION

Anal cancer is uncommon, yet it presents many challenges, including the need for permanent colostomy in most patients. According to the American Cancer Society, there have been 9440 new cases of anal cancer in the United States in 2022 and the number of new cases has been on the rise in the last few decades.1

There are two main histologic types of anal cancer: squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adenocarcinoma. SCC accounts for more than 70% of anal cancers whereas adenocarcinoma represents approximately 5%–10% of cases. These incidences are in contrast to rectal cancer where adenocarcinomas are the most prevalent histology.2, 3 The exact origin of anal adenocarcinomas is not clear. The colorectal type of anal adenocarcinomas originates from the glandular cells of the transitional zone mucosa, whereas the extra-mucosal type originates from the anal canal glands and is usually associated with chronic untreated anal fistulas.3, 4

According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, anal adenocarcinomas are managed with a similar strategy to rectal adenocarcinomas, with multi-modality treatment that includes neoadjuvant therapy followed by abdominoperineal resection (APR).5 This management strategy is different from the treatment of anal SCC, which involves sphincter-preserving radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy as the standard treatment, reserving APR for locally recurrent disease.6

A previous National Cancer Database (NCDB) study7 compared the treatment paradigms and outcomes of stage II–III anal SCC and adenocarcinomas. The study found that there were no significant differences in overall survival (OS) of patients with anal adenocarcinomas according to the treatment type, whereas treatment of SCC with chemoradiation alone was associated with 33% lower mortality. However, the previous analysis did not match the treatment groups of anal adenocarcinoma for demographics and disease stage. Therefore, we conducted the present study to assess the impact of neoadjuvant therapy on the outcomes of APR in patients with stage II–III anal adenocarcinomas after matching for baseline confounders using the propensity-score matched method.

2 PATIENTS AND METHODS

2.1 Study design and setting

A retrospective cohort analysis of patients with anal adenocarcinoma included in the US NCDB between 2010 and 2020 was conducted. The NCDB includes hospital registry data from >1500 Commission on Cancer (CoC) accredited hospitals in the United States. The American College of Surgeons and the CoC have not verified and are not responsible for the analytic or statistical methodology employed, or the conclusions drawn from these data by the investigator.

2.2 Ethical considerations and reporting

Institutional review board/ethics committee approval and written informed consent to participate in the study were not required as the present study is a retrospective analysis of a public database that entails deidentified patient data. The study has been reported in compliance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guideline.

2.3 Study population

Patients included to the study had TNM stage II–III anal adenocarcinoma (International Classification of Diseases Oncology [ICDO]-3 codes 8140/3, 8480-8481/3, 8490/3) who underwent APR with known neoadjuvant status.

-

Patients with other anal cancer pathologies.

-

Patients with stage I or stage IV disease or with unknown TNM stage.

-

Patients who did not undergo surgery or who underwent local excision or had a non-specified surgery.

-

Patients with unknown neoadjuvant status.

2.4 Data collection

The NCDB Participant User File (PUF) was reviewed using the relevant PUF dictionary to interpret the different data variables. The following data were collected and used for the analysis: age, sex, race, Charlson score, residence area, insurance status, facility type, clinical and pathologic TNM stage, tumor histology, grade, size, lymphovascular invasion, surgical approach, conversion to open surgery, hospital stay, 30-day mortality, 90-day mortality, 30-day readmission, and OS.

2.5 Study strategy and outcomes

This study classified patients with anal adenocarcinoma into two groups: neoadjuvant therapy group (patients who received neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy) and no-neoadjuvant group. The two groups were compared for baseline characteristics and were matched for potential clinically relevant confounders with a standardized mean difference >0.2, implying a significant imbalance between the two groups. The groups were matched using the nearest neighbor propensity-score matching method with a 2:1 allocation ratio and a caliper of 0.2, as recommended in previous literature.8 The primary outcome of the study was 5-year OS, whereas secondary outcomes included conversion to open surgery, hospital stay, surgical margins, 30-day mortality, 90-day mortality, and 30-day readmission.

2.6 Addressing bias

To minimize sampling bias and have a representative sample, we used data from a large national database. To reduce selection bias, we selected consecutive patients from the database and used propensity-score matching to match the two groups.

2.7 Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using EZR (version 1.55)9 and R software (version 4.1.2) and SPSS™ (version 23). Continuous data were expressed as mean and standard deviation when normally distributed or otherwise as the median and interquartile range (IQR). The Student t-test or Mann–Whitney test was used to analyze continuous variables. Categorical data were expressed in the form of numbers and proportions and were analyzed using Fisher exact test or Chi-Square test. A complete case analysis approach was used to deal with missing data. Kaplan–Meier, log-rank test, and Cox regression analysis were used to detect significant differences in OS between the two groups. All p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Description of the entire cohort

After screening the records of 5594 patients with anal adenocarcinoma, 742 patients met the study criteria and were included (Figure 1). A total of 417 (56%) patients were male and the mean age was 63.6 ± 12.4 years. The majority of (84%) patients were white while 11.6% were Black and 2.8% were of Asian origin. A total of 22.4% of patients had a Charlson score ≥1. The majority (97.4%) of patients lived in metropolitan or urban areas. A total of 50% of patients had stage II disease and 50% had stage III disease. A total of 81.4% of adenocarcinomas were not-specified, whereas 16.6% were mucinous adenocarcinomas and 2% were signet-ring cell carcinomas. A total of 27.5% of adenocarcinomas were of high grade. The 5-year OS rate was 56.2% and the median follow-up was 51.4 months (IQR: 29–81.2).

3.2 Baseline characteristics

Before matching, neoadjuvant therapy was given to 553 (74.5%) patients whereas 189 (25.5%) underwent APR without neoadjuvant therapy. Patients who received neoadjuvant therapy were younger (61.9 vs. 68.7 years), healthier (Charlson score 0: 80.1% vs. 70.4%), had more private insurance (44% vs. 24.3%), more stage III disease (54.4% vs. 37%), and less poorly differentiated/undifferentiated carcinomas (25.6% vs. 32.9%). After matching for the covariates that showed a significant imbalance (age, Charlson score, clinical TNM stage, insurance, grade), 214 patients in the neoadjuvant group were matched with 107 in the no-neoadjuvant group (Table 1).

| Factor | Group | Before matching | After matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neoadjuvant (n = 533) | No neoadjuvant (n = 189) | SMD | Neoadjuvant (n = 214) | No neoadjuvant (n = 107) | SMD | ||

| Mean age in years (SD) | 61.93 (11.79) | 68.68 (12.86) | 0.548 | 66.63 (11.53) | 66.04 (12.02) | 0.05 | |

| Sex (%) | Male | 319 (57.7) | 98 (51.9) | 0.117 | 131 (61.2) | 52 (48.6) | 0.256 |

| Female | 234 (42.3) | 91 (48.1) | 83 (38.8) | 55 (51.4) | |||

| Race (%) | White | 463 (84.0) | 158 (84.0) | 0.068 | 183 (85.9) | 90 (84.1) | 0.164 |

| Black | 64 (11.6) | 22 (11.7) | 21 (9.9) | 12 (11.2) | |||

| Asian | 15 (2.7) | 6 (3.2) | 6 (2.8) | 4 (3.7) | |||

| American Indian | 3 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Other | 6 (1.1) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.9) | |||

| Charlson Deyo Score (%) | 0 | 443 (80.1) | 133 (70.4) | 0.288 | 156 (72.9) | 80 (74.8) | 0.058 |

| 1 | 79 (14.3) | 46 (24.3) | 43 (20.1) | 20 (18.7) | |||

| 2 | 21 (3.8) | 9 (4.8) | 12 (5.6) | 6 (5.6) | |||

| 3 | 10 (1.8) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.4) | 1 (0.9) | |||

| Residence area (%) | Metro | 435 (80.7) | 147 (79.9) | 0.052 | 167 (80.3) | 84 (81.6) | 0.081 |

| Urban | 89 (16.5) | 33 (17.9) | 37 (17.8) | 18 (17.5) | |||

| Rural | 15 (2.8) | 4 (2.2) | 4 (1.9) | 1 (1.0) | |||

| Facility type (%) | Academic/Research Program | 213 (39.7) | 69 (37.1) | 0.189 | 81 (38.8) | 41 (39.4) | 0.231 |

| Community Cancer Program | 38 (7.1) | 7 (3.8) | 15 (7.2) | 4 (3.8) | |||

| Comprehensive Community Cancer Program | 190 (35.4) | 79 (42.5) | 74 (35.4) | 45 (43.3) | |||

| Integrated Network Cancer Program | 95 (17.7) | 31 (16.7) | 39 (18.7) | 14 (13.5) | |||

| Insurance (%) | Medicaid | 55 (10.1) | 12 (6.5) | 0.547 | 22 (10.3) | 9 (8.4) | 0.087 |

| Medicare | 214 (39.2) | 121 (65.4) | 120 (56.1) | 62 (57.9) | |||

| Other Government | 8 (1.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.9) | |||

| Private | 240 (44.0) | 45 (24.3) | 63 (29.4) | 31 (29.0) | |||

| Not insured | 29 (5.3) | 6 (3.2) | 8 (3.7) | 4 (3.7) | |||

| Clinical TNM (%) | II | 252 (45.6) | 119 (63.0) | 0.355 | 116 (54.2) | 58 (54.2) | <0.001 |

| III | 301 (54.4) | 70 (37.0) | 98 (45.8) | 49 (45.8) | |||

| Grade (%) | Well-differentiated | 39 (9.6) | 20 (13.4) | 0.23 | 25 (11.7) | 14 (13.1) | 0.137 |

| Moderately differentiated | 264 (64.9) | 80 (53.7) | 127 (59.3) | 59 (55.1) | |||

| Poorly differentiated | 93 (22.9) | 44 (29.5) | 55 (25.7) | 32 (29.9) | |||

| Undifferentiated | 11 (2.7) | 5 (3.4) | 7 (3.3) | 2 (1.9) | |||

| Histology (%) | Adenocarcinoma | 459 (83.0) | 145 (76.7) | 0.167 | 177 (82.7) | 84 (78.5) | 0.107 |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 85 (15.4) | 38 (20.1) | 31 (14.5) | 19 (17.8) | |||

| Signet ring cell carcinoma | 9 (1.6) | 6 (3.2) | 6 (2.8) | 4 (3.7) | |||

| Median tumor size in mm [IQR] | 40.00 [27.00, 60.00] | 40.00 [28.00, 53.00] | 0.112 | 35.00 [25.00, 51.00] | 35.00 [28.00, 45.00] | 0.215 | |

- Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; SMD, standardized mean difference

3.3 Treatments and clinical outcomes

Patients who received neoadjuvant therapy had a longer median time between diagnosis and surgery (151 vs. 54 days, p < 0.001) than patients who did not have neoadjuvant therapy. Neoadjuvant therapy was associated with lower 90-day mortality (1.9% vs. 6.7%, odds ratio = 0.27, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.08–0.94, p = 0.046). Both groups had similar conversion rates (8.6% vs. 7.1%, p = 1), median hospital stay (7 vs. 6, p = 0.538), 30-day mortality (1.4% vs. 2.9%, p = 0.402), and 30-day unplanned readmission (8.2% vs. 9.4%, p = 0.782) (Table 2).

| Before matching | After matching | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Group | Neoadjuvant (n = 533) | No neoadjuvant (n = 189) | p value | Neoadjuvant (n = 214) | No neoadjuvant (n = 107) | p value |

| Median days from diagnosis to surgery [IQR] | 154 [131, 189] | 52.00 [27, 83] | <0.001 | 151 [126, 181] | 54 [25.5, 76.75] | <0.001 | |

| Surgical approach (%) | Open | 239 (54.4) | 107 (63.7) | 0.039 | 102 (59.3) | 65 (69.9) | 0.167 |

| Laparoscopic | 102 (23.2) | 38 (22.6) | 38 (22.1) | 18 (19.4) | |||

| Robotic-assisted | 98 (22.3) | 23 (13.7) | 32 (18.6) | 10 (10.8) | |||

| Regional lymph node surgery (%) | No | 27 (5.0) | 9 (4.8) | 1 | 9 (4.3) | 7 (6.5) | 0.42 |

| Yes | 518 (95.0) | 180 (95.2) | 202 (95.7) | 100 (93.5) | |||

| Adjuvant radiation (%) | No | 546 (98.7) | 128 (67.7) | <0.001 | 211 (98.6) | 76 (71.0) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 7 (1.3) | 61 (32.3) | 3 (1.4) | 31 (29.0) | |||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy (%) | No | 396 (71.6) | 114 (59.9) | 0.004 | 161 (75.2) | 63 (58.9) | 0.003 |

| Yes | 157 (28.4) | 75 (40.1) | 53 (24.8) | 44 (41.1) | |||

| Conversion to open surgery (%) | No | 185 (92.5) | 58 (95.1) | 0.773 | 64 (91.4) | 26 (92.9) | 1 |

| Yes | 15 (7.5) | 3 (4.9) | 6 (8.6) | 2 (7.1) | |||

| Median hospital stay in days [IQR] | 6.00 [4.25, 9.00] | 6.00 [4.00, 9.00] | 0.621 | 7.00 [5.00, 9.00] | 6.00 [4.00, 9.00] | 0.538 | |

| 30-Day mortality (%) | No | 525 (98.9) | 172 (97.2) | 0.154 | 207 (98.6) | 101 (97.1) | 0.402 |

| Yes | 6 (1.1) | 5 (2.8) | 3 (1.4) | 3 (2.9) | |||

| 90-Day mortality (%) | No | 520 (98.5) | 167 (94.4) | 0.005 | 205 (98.1) | 97 (93.3) | 0.046 |

| Yes | 8 (1.5) | 10 (5.6) | 4 (1.9) | 7 (6.7) | |||

| 30-Day readmission (%) | No | 502 (93.1) | 172 (92.5) | 0.915 | 189 (91.3) | 95 (89.6) | 0.782 |

| Planned | 7 (1.3) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.9) | |||

| Unplanned | 30 (5.6) | 12 (6.5) | 17 (8.2) | 10 (9.4) | |||

| Median follow-up in months [IQR] | 53.64 [30.42, 86.92] | 47.08 [25.53, 73.46] | 0.011 | 53.59 [29.24, 84.96] | 48.42 [23.74, 71.54] | 0.082 | |

- Note: Bold text in p value columns indicates statistical significance.

- Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

3.4 Pathologic outcomes and survival

Patients who received neoadjuvant therapy had more pT0 tumors (15.7% vs. 0%), fewer pT3-4 tumors (28.4% vs. 36.4%, p = 0.001), fewer pN1-2 tumors (22.9% vs. 34.7%, p < 0.001), more pTNM 0–1 disease (24.1% vs. 9.6%, p = 0.021), and less lymphovascular invasion (16.2% vs. 40%, p < 0.001). Neoadjuvant therapy was associated with significantly fewer harvested lymph nodes (median: 11.5 vs. 14, p = 0.009) and fewer involved lymph nodes. The two groups had similar rates of positive surgical margins, high-grade adenocarcinomas, and mucinous tumors (Table 3).

| Before matching | After matching | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Group | Neoadjuvant (n = 533) | No neoadjuvant (n = 189) | p value | Neoadjuvant (n = 214) | No neoadjuvant (n = 107) | p value |

| Pathologic T (%) | 0 | 64 (13.9) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 | 32 (15.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.001 |

| 1 | 69 (15.0) | 12 (7.7) | 29 (14.2) | 11 (11.1) | |||

| 2 | 149 (32.4) | 82 (52.9) | 73 (35.8) | 48 (48.5) | |||

| 3 | 107 (23.3) | 32 (20.6) | 40 (19.6) | 21 (21.2) | |||

| 4 | 37 (8.0) | 19 (12.3) | 18 (8.8) | 15 (15.2) | |||

| IS | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| X | 32 (7.0) | 10 (6.5) | 12 (5.9) | 4 (4.0) | |||

| Pathologic N (%) | 0 | 307 (67.2) | 99 (64.7) | 0.207 | 143 (71.1) | 59 (60.2) | 0.102 |

| 1 | 85 (18.6) | 31 (20.3) | 33 (16.4) | 20 (20.4) | |||

| 2 | 32 (7.0) | 16 (10.5) | 13 (6.5) | 14 (14.3) | |||

| X | 33 (7.2) | 7 (4.6) | 12 (6.0) | 5 (5.1) | |||

| Pathologic TNM (%) | 0 | 15 (4.1) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 | 10 (6.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.021 |

| I | 61 (16.6) | 10 (6.9) | 30 (18.1) | 9 (9.6) | |||

| II | 147 (39.9) | 81 (56.2) | 65 (39.2) | 46 (48.9) | |||

| III | 134 (36.4) | 51 (35.4) | 57 (34.3) | 37 (39.4) | |||

| IV | 11 (3.0) | 2 (1.4) | 4 (2.4) | 2 (2.1) | |||

| Lymphovascular invasion (%) | No | 313 (84.1) | 99 (63.1) | <0.001 | 124 (83.8) | 54 (60.0) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 59 (15.9) | 58 (36.9) | 24 (16.2) | 36 (40.0) | |||

| Surgical margins (%) | Negative | 483 (90.4) | 157 (85.8) | 0.096 | 180 (87.8) | 85 (82.5) | 0.225 |

| Positive | 51 (9.6) | 26 (14.2) | 25 (12.2) | 18 (17.5) | |||

| Median number of examined nodes [IQR] | 12.00 [6.00, 16.00] | 14.00 [9.00, 19.00] | <0.001 | 11.50 [6.00, 16.00] | 14.00 [9.00, 19.00] | 0.009 | |

| Median number of positive nodes [IQR] | 0.00 [0.00, 1.00] | 0.00 [0.00, 1.00] | 0.107 | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | 0.00 [0.00, 2.00] | 0.002 | |

- Note: Bold text in p value columns indicates statistical significance.

- Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Subgroup analysis of the pathologic outcomes according to tumor histology revealed that neoadjuvant radiation was associated with significant downstaging of the T stage in both non-mucinous (p = 0.017) and mucinous/signet ring cell carcinomas (p = 0.008). The rates of complete mucosal response (pT0) were similar in the two groups (15.6% and 16.7%, respectively). Neoadjuvant radiation was associated with a lower incidence of lymphovascular invasion and fewer harvested lymph nodes in both groups (Table 4).

| Factor | Group | Non-mucinous adenocarcinoma | Mucinous and signet-ring cell carcinoma | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neoadjuvant | No neoadjuvant | p value | Neoadjuvant | No neoadjuvant | p value | ||

| Number | 177 | 84 | 37 | 23 | |||

| Lymphovascular invasion (%) | Yes | 19 (15.7) | 26 (37.7) | 0.001 | 5 (19.2) | 10 (47.6) | 0.059 |

| No | 102 (84.3) | 43 (62.3) | 21 (80.8) | 11 (52.4) | |||

| Pathologic T stage (%) | 0 | 26 (15.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.017 | 6 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.008 |

| 1 | 24 (14.4) | 9 (12) | 4 (11.1) | 2 (8.7) | |||

| 2 | 59 (35.3) | 32 (42.7) | 14 (38.9) | 15 (65.2) | |||

| 3 | 29 (17.4) | 19 (25.3) | 11 (30.6) | 2 (8.7) | |||

| 4 | 18 (10.8) | 12 (16) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (13.0) | |||

| X | 11 (6.6) | 3 (4) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (4.3) | |||

| Pathologic N stage (%) | 0 | 117 (71.3) | 46 (61.3) | 0.294 | 25 (69.4) | 13 (56.5) | 0.474 |

| 1 | 27 (16.5) | 15 (20.0) | 6 (16.7) | 5 (21.7) | |||

| 2 | 11 (6.7) | 10 (13.3) | 2 (5.6) | 4 (17.4) | |||

| X | 9 (5.5) | 4 (5.3) | 3 (8.3) | 1 (4.3) | |||

| Pathologic TNM (%) | 0 | 8 (5.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.051 | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.596 |

| 1 | 26 (19.0) | 7 (9.7) | 3 (10.7) | 2 (9.1) | |||

| 2 | 51 (37.2) | 36 (50.0) | 14 (50.0) | 10 (45.5) | |||

| 3 | 49 (35.8) | 27 (37.5) | 8 (28.6) | 10 (45.5) | |||

| 4 | 3 (2.2) | 2 (2.8) | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Surgical margins (%) | Negative | 151 (89.9) | 67 (82.7) | 0.15 | 29 (80.6) | 18 (81.8) | 1 |

| Positive | 17 (10.1) | 14 (17.3) | 7 (19.4) | 4 (18.2) | |||

| Median number of examined lymph nodes [IQR] | 11.00 [6.00, 17.00] | 14.00 [8.00, 18.75] | 0.053 | 12.00 [8.00, 15.00] | 16.00 [12.50, 19.00] | 0.031 | |

| Median number of positive lymph nodes [IQR] | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | 0.00 [0.00, 2.00] | 0.011 | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | 0.00 [0.00, 2.00] | 0.111 | |

- Note: Bold text in p value columns indicates statistical significance.

- Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

The 5-year OS rate of patients who received or did not receive neoadjuvant therapy was similar (52.1% vs. 50%, p = 0.812). The mean OS was statistically similar between the two groups (47.5 vs. 44.8 months, p = 0.253) (Figure 2). Cox regression analysis showed that the omission of neoadjuvant therapy was not associated with a significant increase in the hazards of mortality (hazard ratio = 1.195, 95% CI: 0.857–1.667, p = 0.294).

4 DISCUSSION

In the present study, although neoadjuvant therapy managed to downstage anal adenocarcinomas and achieve favorable pathologic outcomes; OS was similar to patients who did not receive neoadjuvant therapy. Neoadjuvant radiation did not have a significant impact on short-term clinical outcomes, except for lower 90-day mortality.

In the unmatched cohort, neoadjuvant radiation was administered more often to younger and healthier patients, who would predictably tolerate the adverse effects of neoadjuvant treatment better than elderly patients with comorbidities who are assumed to experience more G3/4 toxicities of preoperative chemoradiotherapy.10 Also, patients with more advanced disease were more likely to have neoadjuvant therapy, however, patients with poorly differentiated carcinomas received less neoadjuvant treatment, probably due to the lower response rate these tumors have to neoadjuvant therapy than moderately- and well-differentiated tumors.11

After matching for possible confounders that may introduce selection bias, neoadjuvant therapy was associated with lower pathologic T and N staging than the group that did not receive neoadjuvant treatment. Moreover, approximately 16% of patients who had neoadjuvant therapy achieved a pathologic complete mucosal response, within the range of complete response of rectal cancer to neoadjuvant therapy of 15%–27%.12, 13 Similar to patients with rectal cancer, those with anal carcinoma who achieve a complete response may be eligible for watch and wait strategy with close surveillance14 to avoid non-restorative proctectomy and terminal colostomy that negatively impacts the quality of life.15 Future prospective trials are needed to assess the rates of clinical complete response after neoadjuvant radiation for anal adenocarcinoma that may enable organ preservation. However, it should be noted that while complete mucosal response (pT0) can be accurately assessed using MRI, endoscopy, and biopsy, complete nodal response (pN0) may not be as accurately assessed given the poor concordance between radiologic and pathologic N stage.16

Furthermore, neoadjuvant radiation was able to reduce the incidence of lymphovascular invasion, a negative prognosticator in colorectal cancer,17 to 16% compared to 40% when neoadjuvant therapy was not given. Du18 and colleagues also found neoadjuvant radiation to reduce lymphovascular invasion in rectal cancer by 5%, although this reduction was not statistically significant, probably because the authors used neoadjuvant radiation therapy only, and perhaps the addition of concurrent chemotherapy may enhance the therapeutic effect of radiation on cancer cells involved in the vessels.

Despite the positive downstaging effect of neoadjuvant therapy in achieving favorable pathologic outcomes, it did not prolong OS compared to patients who did not have neoadjuvant therapy. This finding may seem counter-intuitive to the studies that reported improved OS with neoadjuvant therapy for rectal adenocarcinoma.5, 19 However, anal carcinomas are different from rectal carcinomas in many aspects, including tumor biology and lymphatic pathways. A recent NCDB analysis of the trends of anal adenocarcinomas showed that the standard treatment of anal adenocarcinoma with the best survival outcome is surgery preceded by neoadjuvant chemoradiation.20 The lack of a survival benefit of neoadjuvant therapy in our study might be explained by the effect of adjuvant chemotherapy that was given to 41.1% of patients who did not have neoadjuvant therapy versus 24.8% of patients who received neoadjuvant treatment. As also shown in the previous NCDB analysis,20 giving adjuvant therapy after surgery can prolong OS by 6 months compared to surgery alone. This disparity of adjuvant treatment may explain the similar OS since patients who did not receive neoadjuvant therapy and were found to have stage III disease after surgery had adjuvant therapy, whereas patients who were down staged after neoadjuvant therapy did not require adjuvant therapy. Ultimately, both groups had similar OS, indicating that the survival benefit of radiation therapy in stage II–III anal adenocarcinomas is similar, whether given before or after surgery. This finding may help clinicians tailor therapy to each patient, depending on several factors related to the patient's condition and available resources.

Neoadjuvant therapy was associated with a significant reduction in the odds of 90-day mortality in our study. The explanation of this interesting finding is not clear and may be attributed to the downstaging effect of neoadjuvant therapy that may have facilitated radical resection, unlike advanced T4/N1-2 anal carcinomas that were operated on without neoadjuvant treatment, and thus resection might have been demanding and complicated. It is noteworthy that neoadjuvant radiation may be followed by an increased rate of perineal complications and surgical site infections after APR.21, 22 However, neoadjuvant therapy is not significantly associated with higher 30-day or 90-day mortality after rectal cancer surgery.23

Despite the benefits of neoadjuvant therapy, it was associated with a longer period from diagnosis to surgery and fewer harvested lymph nodes than the no-neoadjuvant group. The time from diagnosis to surgery was almost tripled when neoadjuvant therapy was given. However, the prolonged wait before surgery may be justified by the positive downstaging effect of therapy that was able to achieve a complete response in 16% of patients. The fewer number of examined lymph nodes after neoadjuvant therapy has been previously reported in studies on rectal adenocarcinoma. However, as Billakanti et al.24 concluded, although neoadjuvant chemoradiation decreased lymph node harvest in rectal cancer surgery, this reduced nodal harvest does not reduce survival.

It is important to note that, although neoadjuvant radiation therapy was associated with significant downstaging of both mucinous and non-mucinous anal adenocarcinomas, this pathologic benefit did not translate into a tangible survival benefit. This finding emphasizes the importance of selecting patients with stage II/III anal adenocarcinoma for neoadjuvant radiation rather than using it for all patients to avoid unnecessary delay in surgical management and potential postradiation perineal wound complications.

The current analysis adds to the current literature as most previous studies included smaller cohorts or did not match the compared groups for important confounders. The present study is one of the first large studies to assess the benefits of neoadjuvant therapy in anal adenocarcinoma, using propensity-score matching to minimize selection bias. The conclusions of the study, that while neoadjuvant radiation was associated with significant downstaging of anal adenocarcinoma but not a significant survival benefit and that approximately 16% of patients had a complete mucosal response to therapy that may render them candidates for the Watch and Wait strategy, may help inform the current practice and direct future research. However, there are limitations to the study that include its retrospective nature and lack of data on the chemoradiation regimen used and disease-free survival. Stratifying OS by disease stage and patients' demographics was not possible because of the relatively small number of patients included after matching.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Neoadjuvant therapy before APR was associated with significant downstaging of anal adenocarcinomas, reduction of the incidence of lymphovascular invasion, and lower 90-day mortality. However, OS was not improved when neoadjuvant therapy was given before surgery.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Dr. Wexner reports receiving consulting fees from ARC/Corvus, Astellas, Baxter, Becton Dickinson, GI Supply, ICON Language Services, Intuitive Surgical, Leading BioSciences, Livsmed, Medtronic, Olympus Surgical, Stryker, Takeda and receiving royalties from Intuitive Surgical and Karl Storz Endoscopy America Inc. Dr. Emile reports receiving consulting fees from SafeHeal.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

SYNOPSIS

This study aimed to assess the impact of neoadjuvant therapy on the clinical and pathologic outcomes and overall survival (OS) of patients with stage II–III anal adenocarcinomas after abdominoperineal resection (APR). Neoadjuvant therapy before APR was associated with significant downstaging of anal adenocarcinomas and lower 90-day mortality, yet similar OS to patients who were surgically treated without neoadjuvant treatment. Both groups had similar conversion rates, hospital stay, 30-day mortality, 30-day readmission, and positive surgical margins.