From Perceived School Climate to Creativity Performance: The Serial Multiple Mediation of Creative Self-Efficacy and Creativity Motivation

ABSTRACT

Building on social cognitive theory and the multimethod of assessing creativity, we examined the joint mediating effect of creative self-efficacy and creativity motivation on the association between perceived school climate and three dimensions of creativity performance (i.e., idea generation, combinatory ability, and restructuring ability). A total of 687 Chinese schoolchildren (51.2% girls; mean age = 14.8 years) attending secondary schools in Hong Kong completed the study. Perceived school climate, creative self-efficacy, and creativity motivation were assessed via the Perceived School Climate Scale, the Creative Self-Efficacy Scale, and the Creativity Motivation Scale, respectively. The three dimensions of creativity performance were assessed via their corresponding creativity tests (i.e., a divergent thinking test, a gestalt combinatory test, and a creative problem-solving test). Mediation analyses revealed that creative self-efficacy and creativity motivation partially and significantly mediated the link between perceived school climate and the three dimensions of creativity performance as single and serial mediators. The results further illustrated that, in general, the first mediator (creative self-efficacy) tends to have a slightly stronger effect than the second mediator (creativity motivation) in the mediation pathway across the three dimensions of creativity performance. These findings have important theoretical and practical implications.

1 Introduction

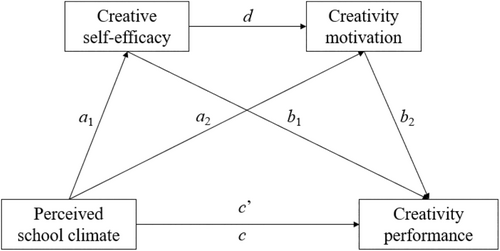

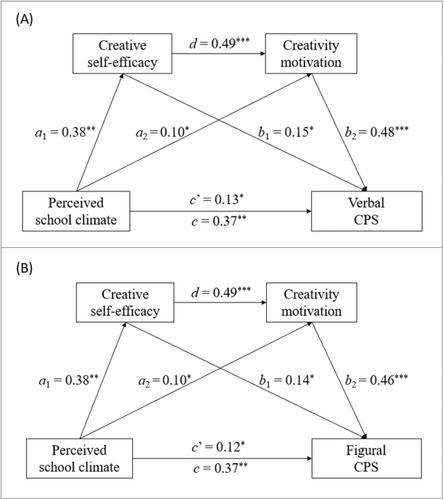

For a long time, fostering student creativity in school settings has been a significant focus of research in the educational and psychological literature (Norris et al. 2023), where creativity is defined as the ability to produce ideas, products, and solutions to a problem that is characterized by both novelty and appropriateness (Beghetto and Karwowski 2023; Karwowski et al. 2018; Sternberg and Lubart 1999). In this context, the perceived school climate, which reflects perceptions of the quality and character of school life, has been identified as a critical school factor that influences student creativity (Greenier et al. 2023). While increasing research has underscored the impact of students' perceptions of the school climate on their creativity (Wang et al. 2023), the mechanisms underlying this relationship remain relatively less explored. We examine this issue through the lens of social cognitive theory (Bandura 1997), which provides a theoretical foundation for hypothesizing that the school climate perceived by students may influence their creativity performance via the joint contribution of two mediators—creative self-efficacy and creativity motivation (see Figure 1 for the hypothesized model).

1.1 School Climate and Creativity

School climate is understood as a multifaceted construct that includes various dimensions, such as learning experiences, relationships, safety, and the institutional environment (Siebert et al. 2024); all of these dimensions can contribute to a supportive or inhibitive atmosphere for creativity (Greenier et al. 2023). In the literature, school climate is typically conceptualized in three ways: a shared perception of school climate, an objective assessment of school climate, and an individual perception of school climate. Firstly, the shared perception of school climate refers to the collective beliefs, attitudes, and perceptions of school community members. Common in organizational psychology, climate is considered an emergent group-level property derived from shared experiences (Marsh et al. 2012). It is often measured by aggregating perceptions from multiple stakeholders, such as students, teachers, and administrators, to form a unified representation of the school environment (Bottiani et al. 2020). Secondly, the objective assessment of school climate is based on external, measurable indicators that are independent of subjective perceptions, including school policies, disciplinary records, student–teacher ratios, and infrastructure quality (Kutsyuruba et al. 2015). Unlike a shared perception of climate, which relies on collective perception, an objective measurement of school climate provides a structural and policy-driven perspective. Finally, the individual perception of school climate refers to individual students' subjective evaluations of the school climate (Marraccini et al. 2020). Unlike a shared or an objective school climate, it is an individual-level construct that reflects personal experiences, emotions, and attitudes towards the school environment.

Given that this study investigates individual student experiences, it adopts the perceived school climate framework. Specifically, this study focuses on students' perceptions of teacher support, peer support, autonomy opportunity, and clarity and consistency in school rules. These dimensions were selected due to their relevance to creativity: for example, students' perceptions of teacher support are linked to enhanced creative thinking through creative self-efficacy (Zhang et al. 2020); students' perceptions of peer support foster creativity by enhancing collaboration and engagement in creative processes (Zamberlan and Wilson 2017); and students' perceptions of autonomy support foster creativity by encouraging personal investment and engagement in creative projects (Sullivan 2015). Students' perceptions of clarity and consistency in school rules foster creativity by contributing to a supportive and structured learning environment (McCharen et al. 2011).

Indeed, researchers have highlighted that a positive school climate for creativity is typically characterized by key features such as supportive relationships, a sense of trust, safety, respect, and belongingness, achievable expectations, inclusion, and equal opportunities for success, as well as a climate that encourages autonomy, intellectual risk-taking, and innovation (Greenier et al. 2023; Martinsone et al. 2023). Empirical findings have revealed positive associations between these characteristics and creativity. For instance, Brauer et al. (2024) demonstrated that teachers who encourage student autonomy, provide constructive feedback, and facilitate open communication likely promote creative expression and behaviors among students. Norris et al. (2023) reported that classrooms that emphasize collaborative learning and respect for diverse perspectives likely enhance the creative capacities of students by fostering curiosity. Demchenko et al. (2021) reported that students who perceive their school environment as inclusive and supportive are more likely to engage in creative activities. Moreover, Zhang et al. (2020) reported that students who perceive their teachers as autonomy-promoting and supportive tend to perform better in creative thinking and creative problem-solving tasks. In short, research evidence supports the vital role of a positive school climate in facilitating student creativity.

1.2 Agentic Perspective on the Underlying Mechanism

Compared with the growing body of research illustrating the positive relationship between school climate and student creativity, the mechanisms underlying this relationship remain relatively underresearched. However, uncovering these mechanisms is crucial for understanding how and when school factors can be structured to foster student creativity, which then further informs effective educational design and intervention implementation (Greenier et al. 2023). Notably, Bandura's (1997) social cognitive theory offers important insights that illuminate the issue from an agentic perspective. This perspective emphasizes that people are not merely passive receivers of environmental input but also play an active agentic role in interplaying with their living environment to influence functioning outcomes. Regarding the psychological processes underlying this agentic role, Bandura (1997) proposed a mechanism that involves the joint mediating effect of two psychological attributes (i.e., self-efficacy and motivation), by which environmental inputs impact functioning outcomes (see also Bandura 2023). In the school climate-creativity context, a perceived school climate may contribute to student creativity performance through the concerted mediating effect of creative self-efficacy and creativity motivation. Below is an elaboration.

1.2.1 Creative Self-Efficacy as a Mediator

In social cognitive theory (Bandura 1997), creative self-efficacy is conceptualized as a specific type of self-efficacy that pertains to the self-beliefs of people in their ability to produce creative ideas, products, solutions, and behaviors (Tierney and Farmer 2002). Creative self-efficacy is emphasized as an essential prerequisite for achieving creative productivity, where it represents an internal, sustaining force that propels individuals to persevere in creative work (Tierney and Farmer 2011). This notion emphasizes that unless people believe in their ability to do so, they may not engage in a particular creative behavior even when they are capable of performing that behavior (Beghetto and Karwowski 2023). In fact, empirical findings illustrate that when students have a greater sense of creative self-efficacy, they tend to demonstrate more creative behaviors, such as experimenting with new ideas, taking intellectual risks, and persisting in the face of setbacks during the creative process (Kim et al. 2019). Further empirical evidence suggests that creative self-efficacy is positively related to multiple aspects of creative functioning, such as original and flexible thinking (Du et al. 2020), creative problem solving (Royston and Reiter-Palmon 2019), the use of creative cognition (He and Wong 2022a), and the expression of creative behaviors (Liang et al. 2023). Hence, an increasing number of researchers and educators suggest promoting student creativity by cultivating creative self-efficacy (Puozzo and Audrin 2021).

According to Bandura (1997), (creative) self-efficacy can be fostered by four main sources of influence, including (1) mastery experiences (i.e., self-learning experiences), (2) vicarious experiences (i.e., observational learning from others), (3) social persuasion (i.e., feedback from significant others), and (4) physiological states (i.e., emotional and mental states). In terms of school factors, the perception of a school climate characterized by these sources is suggested to have a positive effect on student creative self-efficacy (Zysberg and Schwabsky 2021). For example, students can develop greater creative self-efficacy when they perceive their school environment, enabling them to (1) achieve success through effort (mastery experiences), (2) learn from peer success (vicarious experiences), (3) receive positive feedback from teachers (social persuasion), and (4) feel secure and happy (favorable emotional and physiological states). Research evidence reveals that a positive school climate, marked by an inspiring academic environment, supportive relationships, and constructive feedback, is associated with increased self-efficacy among students (Khuhro 2024). Positive peer interactions and collaborative learning experiences likely contribute to a greater sense of competence and belongingness, which in turn facilitates the positive development of student self-efficacy (Huang 2023). Additionally, teachers who provide supportive and constructive feedback tend to promote student self-confidence in their competence (Rustamov et al. 2023). Collectively, these studies provide theoretical and empirical ground for anticipating the mediating role of creative self-efficacy in linking perceived school climate and student creativity performance.

1.2.2 Creativity Motivation as a Mediator

Within the framework of social cognitive theory (Bandura 1997), creativity motivation—conceptualized as an activation engine that initiates, energizes, and sustains creative actions (He 2023a)—is highlighted as another important mediator in the pathways of transforming the effect of the perceived school climate into student creativity performance. According to this perspective, people are motivated to guide their behavioral actions according to their self-beliefs in their competence in performing a task. Hence, task motivation functions as a mediator in directing the effect of self-efficacy on functional outcomes (Bandura 2023). In Bandura's (1994) words, “… self-efficacy beliefs contribute to motivation… (by determining) the goals people set for themselves; how much effort they expend; how long they persevere in the face of difficulties; and their resilience to failures… (which) contributes to performance accomplishments…” (p. 5). Other researchers (e.g., Schunk and DiBenedetto 2021) also noted that self-efficacy impacts functioning outcomes via task motivation, which determines the choice of activities, level of effort and persistence, and type and intensity of emotional reactions. In this vein, research findings illustrate that students who have a greater sense of self-efficacy are motivated to engage more in the behavior that they perceive as leading to desired outcomes, which in turn contributes to more promising outcomes (Bandhu et al. 2024).

In the literature on creativity, on the one hand, an increasing amount of research has documented a positive link between creative self-efficacy and task motivation (Xiang et al. 2023). On the other hand, many theories on creativity (e.g., the componential model of creativity, Amabile 2011; the systems model of creativity, Csikszentmihalyi 2015) have highlighted motivation as an essential engine that drives creative behaviors and sustains creative efforts. All these theories highlight that motivation, especially intrinsic motivation, functions as a critical component that interacts with other components of creativity (e.g., cognitive and environmental components) to influence creative outcomes. These theories emphasize that motivation contributes to creative endeavors via the psychological mechanism of goal setting, self-regulation, and persistence in investing time and sustaining effort (see also He 2023a). In accordance with this notion, research findings have shown that creative self-efficacy impacts creativity performance through a motivational mechanism that determines individual engagement in creative endeavors (Bai et al. 2023; Du et al. 2020). In short, these studies collectively provide theoretical and empirical ground for hypothesizing a motivational pathway by which creative self-efficacy affects creativity performance.

1.3 Present Study

An integration of the literature presented in Sections 1.1 and 1.2 leads to the anticipation that the school climate perceived by students may indirectly impact their creativity performance via the joint mediating effect of creative self-efficacy and creativity motivation through multiple pathways (see Figure 1). These pathways may include (1) creative self-efficacy as a single mediator linking perceived school climate and creativity performance (i.e., paths a1 × b1); (2) creativity motivation as a single mediator linking perceived school climate and creativity performance (i.e., paths a2 × b2); and (3) creative self-efficacy and creativity motivation as serial mediators linking perceived school climate and creativity performance in a sequential manner (i.e., paths a1 × d × b2). These multiple pathways work in concert to mediate the effect of perceived school climate on student creativity performance. While separate lines of research have illustrated the individual influences of the school climate (e.g., Greenier et al. 2023), creative self-efficacy (e.g., He and Wong 2022a), and creativity motivation (e.g., Zhang et al. 2023) on creative outcomes, how these factors work together in synergy to affect creative outcomes has been less explored. Building on social cognitive theory, we aim to fill this research gap by examining this synergistic effect. Moreover, by understanding the intricate relationships within one comprehensive model, we aim to provide new insights into the mechanism that may structure school factors into creative outcomes via effective regulation of psychological processes that involve cognitive and motivational components.

Furthermore, we aim to take one more step forward by testing the hypothesized mediating effects via the application of a multimethod approach to assessing creativity (Runco 2024). Creativity has been acknowledged as a multifaceted construct that requires a multimethod approach to facilitate a more holistic and concise assessment (Sternberg et al. 2024). Recent studies have highlighted the application of Antonietti and Iannello's (2008) taxonomy for assessing creativity across three aspects by using their respective measurements (e.g., Haase et al. 2018; He 2023b, 2024). The first aspect—idea generation—can be measured via a divergent thinking test such as the Wallach-Kogan Creativity Test (WKCT; Wallach and Kogan 1965). The WKCT is one of the classical tests for assessing creativity associated with divergent production (He and Wong 2021a). The second aspect—combinatory ability—can be measured via the Test for Creative Thinking–Drawing Production (TCT–DP; Urban and Jellen 1996), which is rooted in gestalt psychology and assesses creative ability related to integrating innovation and appropriateness to merge disjointed cohesive and meaningful structures (He and Wong 2022b). Finally, the third aspect—restructuring ability—is measured via a creative problem-solving test (CPST; He and Wong 2021a), which reveals the capacity to generate novel and appropriate solutions through a revised interpretation and representation of a problem (Weisberg 2015).

Through the lens of social cognitive theory and the multimethod approach to creativity assessment, we hypothesize that the chain mediation model depicted in Figure 1 is supported in the three dimensions of creativity performance, including idea generation, as reflected by the WKCT scores (Hypothesis 1); creative combinatory ability, as reflected by the TCT–DP scores (Hypothesis 2); and restructuring ability, as reflected by the CPST scores (Hypothesis 3).

2 Method

2.1 Participants and Procedures

A convenient sampling method was applied to recruit participants. A letter of invitation was sent to all government-aided secondary schools in Hong Kong via the school lists available publicly on the website of the Education Bureau (EDB 2025). After communication about the research objectives and methods between the research team and the interested schools that responded to the invitation, a total of four coeducation schools were selected as participating schools based on their willingness to participate, administrative approval, geographic accessibility, and research budget considerations. The initial sample consists of 708 9th–12th graders. Among them, 21 (2.97%) were removed from the formal data analysis due to missing data, yielding a final sample that consisted of 687 participants (51.2% girls), with 172 (25%) 9th graders, 181 (26%) 10th graders, 169 (25%) 11th graders, and 165 (24%) 12th graders. All participation was voluntary. The mean age and average education level of the final sample were 14.8 years (SD = 1.43, range = 14–17 years) and 11.2 years (SD = 1.66; range = 10–14 years), respectively. Based on the data from the participating schools, all admitted students were from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds, primarily middle- and lower-middle-class. Furthermore, all the participating students were of Chinese ethnicity. Before data collection, the student participants and their parents were provided with research information outlining the study's objectives, as well as the principles of confidentiality, anonymity, and safety. Informed consent was secured from the participating schools. Only those students who provided both their own assent and informed consent from their parents received an invitation to participate. During data collection, participants completed assessments of the study variables (i.e., perceived school climate, creative self-efficacy, creativity motivation, and creativity performance) in a regular classroom setting with a group size of approximately 30–40 students, following standard instructions. The entire assessment procedure lasted approximately 50–60 min.

2.2 Instruments

2.2.1 Perceived School Climate

The adapted Chinese version of the Perceived School Climate Scale (PSCS; Way et al. 2007) was used to evaluate students' perceptions of the school climate. The PSCS was developed on the basis of the Classroom Environment Scale (Trickett and Moos 1973), which is a widely used and well-validated measure for assessing the school climate as perceived by students (Zhang and Wang 2020). The scale assesses perceived school climate according to four dimensions: (1) teacher support (e.g., “Teachers go out of their way to help students”), (2) peer support (e.g., “Students get to know each other well in classes”), (3) student autonomy (e.g., “In our school, students are given the chance to help make decisions”), and (4) clarity and consistency in school rules (e.g., “Students understand what will happen to them if they break a rule”). The participants responded on a 5-point scale (from 1 = never to 5 = always) to indicate their agreement on how true the statements were for their perception of the school climate. Previous research (Zhang and Wang 2020) has validated the psychometric properties of the PSCS among Chinese students in mainland China, reporting a satisfactory Cronbach's α of 0.81 and acceptable fit indices from confirmatory factor analysis (CFA: TLI = 0.864, CFI = 0.879, SRMR = 0.034, RMSEA = 0.043).

Since this study is the first to apply this adapted Chinese version of the scale to Chinese students in Hong Kong, we conducted a CFA to determine its construct validity using SPSS AMOS 28.0 with maximum likelihood estimation. By reference to previous research regarding the conceptual framework for students' perceived school climate (Way et al. 2007; Zhang and Wang 2020), we examined the factorial structure validity of the scale on four models: a 1-factor model in which all scale items loaded on one single factor—perceived school climate (Model 1); a 4-factor model that consisted of the four dimensions of perceived school climate—teacher support, peer support, student autonomy, and clarity and consistency in school rules—both with (Model 2) and without correlated factors (Model 3); a second-order model that featured one overarching second-order factor—perceived school climate—which comprises teacher support, peer support, student autonomy, and clarity and consistency in school rules as the four first-order subfactors (Model 4). Table 1 presents the results of the model-fit indices, which revealed that Model 1 exhibited the strongest model fit in comparison with the other three models and met the relevant criteria for acceptable goodness-of-fit (Hu and Bentler 1999). Table 2 presents the factor loadings of all scale items, which ranged from 0.64 to 0.82. All of these values were greater than the relevant criterion of 0.50 (Hair et al. 2014). Overall, these results suggest that a general single factor accounts for perceived school climate among the sample of Chinese students investigated in this context. Regarding the reliability of the scale, a Cronbach's α = 0.86 was obtained, thus supporting the measure's internal consistency.

| Model | Model specification | χ 2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 1-first-order-factor model | 492 | 170 | 2.894 | 0.904 | 0.924 | 0.079 | 0.060 |

| Model 2 | 4-first-order-factor model with correlated factors | 710 | 164 | 4.329 | 0.801 | 0.813 | 0.097 | 0.098 |

| Model 3 | 4-first-order-factor model without correlated factors | 994 | 170 | 5.847 | 0.746 | 0.791 | 0.099 | 0.098 |

| Model 4 | 1-second-order-factor model with 4 subfactors | 528 | 170 | 3.106 | 0.893 | 0.884 | 0.095 | 0.089 |

- Note: Ideal model-fit indices recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999): χ2/df < 3.00, CFI and TLI ≥ 0.95 (good) or ≥ 0.90 (acceptable); RMSEA and SRMR ≤ 0.06 (good) or ≤ 0.08 (acceptable).

- Abbreviations: CFI, Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; SRMR, Standardized Root Mean Square; TLI, Tucker Lewis Index.

| English item | Chinese translation | Factor load |

|---|---|---|

| Dimension 1: Teacher Support | ||

| 1. Teachers take a personal interest in students. | 1. 教師關注學生個別需要。 | 0.81 |

| 2. Teachers go out of their way to help students. | 2. 教師竭盡所能幫助學生。 | 0.78 |

| 3. Teachers will find time to do it if students want to talk about something. | 3. 如果學生想與教師討論一些事情, 教師願意花時間進行討論。 | 0.73 |

| 4. Teachers help students to organize their work. | 4. 教師會幫助學生組織他們的工作。 | 0.72 |

| 5. Teachers help students catch up when they return from an absence. | 5. 教師會幫助缺課的學生趕上進度。 | 0.74 |

| Dimension 2: Peer Support | ||

| 6. Students in this school are mean to each other.a | 6. 這所學校的學生彼此之間並不友善。a | 0.71 |

| 7. Students in this school have trouble getting along with each other.a | 7. 這所學校的學生彼此之間相處困難。a | 0.73 |

| 8. Students in this school are very interested in getting to know other students. | 8. 這所學校的學生熱衷於認存其他同學。 | 0.78 |

| 9. Students in this school get to know each other well in classes. | 9. 在這所學校, 同班同學之間相互熟悉。 | 0.79 |

| 10. Students in this school enjoy doing things with each other in school activities. | 10. 這所學校的學生喜歡一起參加校內活動。 | 0.82 |

| Dimension 3: Student Autonomy | ||

| 11. Students in this school have a say in how things work. | 11. 本校學生對學校一些事務的運作有發言權。 | 0.64 |

| 12. Students are given the chance to help decide class rules. | 12. 學生有機會參與班規的制定。 | 0.73 |

| 13. Students are given the chance to help make decisions. | 13. 學生有機會參與協助做一些決定。 | 0.71 |

| 14. Students get to help decide some of the rules in this school. | 14. 學生可以參與制定學校的一些規則。 | 0.66 |

| 15. Teachers ask students what they want to learn about. | 15. 教師會諮詢學生想學什麼。 | 0.82 |

| Dimension 4: Clarity and Consistency in School Rules | ||

| 16. Teachers make a point to sticking to the rules in classes. | 16. 教師在課堂上注重遵守規則。 | 0.73 |

| 17. When teachers make a rule, they mean it. | 17. 當教師制定規則時, 他們會認真執行。 | 0.74 |

| 18. Students are given clear instructions about how to do their work in classes. | 18. 學生在課堂上會獲得清晰的工作指示。 | 0.81 |

| 19. Students understand what will happen to them if they break a rule. | 19. 學生知道假如他們違反學校規則會有什麼後果。 | 0.71 |

| 20. If students are acting up in class, teachers will do something about it. | 20. 假如學生在課堂上行為不當, 教師會採取措施。 | 0.78 |

- Abbreviation: PSCS, Perceived School Climate Scale.

- a Reversed item.

2.2.2 Creative Self-Efficacy

The Chinese version of the Creative Self-Efficacy Scale (He and Wong 2021b; Karwowski 2012) was used to assess creative self-efficacy. An example of a test item is “I am confident in my creative abilities”. The responses of the participants to each statement were scored on a 5-point scale (5 = definitely yes; 1 = definitely not). The psychometric properties of this scale have been well supported in studies on creative self-efficacy that have been conducted in school settings (Karwowski et al. 2018). The applicability of the Chinese version of the scale has also been supported among Chinese students (He and Wong 2021b, 2022a). In the present study, a high Cronbach's α = 0.85 was obtained to support its internal consistency.

2.2.3 Creativity Motivation

The Chinese version of the Creativity Motivation Scale (CMS; He 2023a) was used to assess creativity motivation. Zhang et al. (2018) developed the CMS based on the understanding that creativity motivation is the driving force that compels individuals to participate in three domains of creative endeavors, including learning, experimentation, and the pursuit of innovative outcomes. An example of the test items is “I experience pleasure when I discover new things that I have never seen before”. The participants responded on a 6-point scale (6 = strongly agree; 1 = strongly disagree) to indicate their agreement with the statement. Previous studies have supported the reliability, validity, and applicability of the scale in Chinese student samples (He 2023a; Li et al. 2021). A high Cronbach's α = 0.84 was obtained in this study to support its internal reliability.

2.2.4 Creativity Performance

2.2.4.1 Idea Generation

The Chinese version of the WKCT (Wallach and Kogan 1965; Cheung et al. 2004) was used to evaluate the ability to produce a wide range of ideas in large quantities. The WKCT has demonstrated reasonably good psychometric properties (He 2023b, 2024; He and Wong 2021a). In this study, the Chinese WKCT included both verbal and figural test items. The verbal test items featured alternate uses tasks (e.g., listing as many possible uses for a newspaper). The figural test items include pattern interpretation tasks, which require participants to generate as many meanings or associations as possible based on a given pattern. A total of 5 min were allowed to respond to each of the test items. Idea generation was scored by using two indices. First, fluency is scored by the total number of ideas. Second, flexibility is scored by the total number of categories into which the given ideas could be classified. Two experienced creativity researchers were employed to evaluate all the responses, and the average of their scores was used for data analysis. The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) suggested high interrater reliability, with all the ICCs greater than 0.90 (ICCVerbal_fluency = 0.95; ICCVerbal_flexiblity = 0.95; ICCFigural_fluency = 0.96; ICCFigural_flexiblity = 0.94; p values < 0.001). Furthermore, α = 0.85–0.88 was also found to support the internal consistency of the test in this sample (see Table 5).

2.2.4.2 Creative Combinatory Ability

The Chinese version of the TCT–DP (Form A, Urban and Jellen 1996; He and Wong 2011) was employed to evaluate creative combinatory ability (Haase et al. 2018; He 2024). Specifically, the test assesses creative combinatory ability via a drawing task on an A4-sized sheet containing six distinct figural fragments: (a) a small open square, (b) a broken line, (c) a curved line, (d) a 90° angle, (e) a semicircle, and (f) a point. Participants can complete the drawing by assembling these fragments in various ways, from basic, conventional, typical, and separate arrangements to intricate, unconventional, atypical, cohesive, holistic, and visually compelling compositions. This test has been recognized as a valuable tool for assessing creative thinking, with well-documented psychometric properties in Hong Kong Chinese student samples (He 2023b, 2024). Following the instructions in the test manual, nine criteria were applied to assess creativity performance, including (1) continuation, (2) completion, (3) connections by line, (4) connections by theme, (5) new elements, (6) boundary breaking, (7) unconventionality, (8) perspective, and (9) humor and affectivity, with a total possible score range of 0–66 points. A higher TCT–DP composite score reflects greater creativity performance (see He and Wong 2011, for more scoring details).

2.2.4.3 Restructuring Ability

The Chinese version of the CPST (Lin et al. 2012; He and Wong 2021a) was used to evaluate creative problem solving by restructuring ability, specifically the sudden realization of a novel and appropriate solution to a given problem (He 2023b; Weisberg 2015). The test consists of a set of 10 test items, among which 5 have verbal test content and the other 5 have figural test content. A verbal test item reads, “How many cubic centimetres of dirt are in a hole 6 metres long, 2 metres wide, and one metre deep?” A figural test item reads, “Nine pigs are kept in a square pen. Build two more square enclosures that would put each pig in a pen by itself” (see He and Wong 2021a and Lin et al. 2012 for more details). A maximum of 20 min was allowed to complete the task. Creative problem-solving performance scores were determined by calculating the percentage of correctly answered verbal and figural problems. Previous studies have supported the reliability, validity, and applicability of the test in Hong Kong and Taiwanese Chinese student samples (He 2023b, 2024; He and Wong 2021a; Lin 2023). The scale exhibited good internal consistency in this study, with reliability coefficients of α = 0.81 for the verbal items and α = 0.80 for the figural items.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed via IBM SPSS version 28.0 for Windows and SPSS PROCESS macro 4.0 software (Hayes 2013), with p < 0.05 indicating statistical significance. Descriptive analyses were first conducted with the variables of interest. Pearson's correlations were then performed as a preliminary analysis of the mediation analyses to examine the bivariate correlations among the study variables. Next, serial multiple mediation analyses were conducted via the SPSS PROCESS macro (Model 6; Hayes 2013) to test Hypotheses 1–3 with respect to the serial multiple mediating effect of creative self-efficacy and creativity motivation between perceived school climate and student creativity performance. Separate mediation models were built for each of the three aspects of creativity performance. Ordinary least squares regression was used to calculate path coefficients for total, direct, and indirect effects. A bias-corrected bootstrapping method with a resampling procedure of 5000 samples was used to calculate the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for the mediation effects. The indirect effect of the mediation path was considered statistically significant if the 95% CI did not include zero.

3 Results

3.1 Bivariate Analyses

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of the key study variables. In line with the hypotheses, the predictor variable (i.e., perceived school climate) was positively correlated with all measures of the outcome variable (i.e., creativity performance; rs = 0.19–0.42, p values < 0.01), as well as with the two mediators—creative self-efficacy (r = 0.42, p < 0.001) and creativity motivation (r = 0.21, p < 0.01). Moreover, these two mediators were also positively correlated with all measures of the outcome variable (i.e., creativity performance), with rs = 0.21–0.55 for creative self-efficacy (p values < 0.01) and rs = 0.53–0.64 for creativity motivation (p values < 0.001).

| Variables | M | SD | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 14.8 | 1.43 | — | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 2. Gender | — | — | — | 0.02 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 3. Education | 11.2 | 1.66 | — | 0.82*** | 0.04 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 4. Perceived school climate | 3.81 | 1.34 | 0.86** | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 1 | |||||||||

| 5. Creative self-efficacy | 3.20 | 1.27 | 0.85** | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.42*** | 1 | ||||||||

| 6. Creativity motivation | 3.57 | 1.63 | 0.84** | 0.05 | 0.11* | 0.04 | 0.21** | 0.55*** | 1 | |||||||

| 7. WKCT-Fluency (verbal) | 17.4 | 9.19 | 0.86** | 0.09 | 0.12* | 0.14* | 0.33** | 0.38** | 0.60*** | 1 | ||||||

| 8. WKCT-Flexibility (verbal) | 3.56 | 1.73 | 0.85** | 0.10* | 0.13* | 0.15* | 0.30** | 0.33** | 0.58*** | 0.39*** | 1 | |||||

| 9. WKCT-Fluency (figural) | 16.9 | 10.1 | 0.87** | 0.11* | 0.14* | 0.13* | 0.32** | 0.36** | 0.62*** | 0.41*** | 0.46*** | 1 | ||||

| 10. WKCT-Flexibility (figural) | 3.28 | 1.94 | 0.88** | 0.12* | 0.12* | 0.12* | 0.27** | 0.29** | 0.59*** | 0.38*** | 0.40*** | 0.41*** | 1 | |||

| 11. TCT–DP | 18.7 | 9.03 | 0.89** | 0.10* | 0.14* | 0.11* | 0.24** | 0.26** | 0.64*** | 0.19** | 0.18* | 0.16* | 0.17* | 1 | ||

| 12. CPST (verbal) | 54.8 | 9.78 | 0.81** | 0.11* | 0.12* | 0.16* | 0.21** | 0.24** | 0.56*** | 0.13* | 0.11* | 0.12* | 0.13* | 0.14* | 1 | |

| 13. CPST (figural) | 53.1 | 10.4 | 0.80** | 0.12* | 0.13* | 0.15* | 0.19** | 0.21** | 0.53*** | 0.16* | 0.12* | 0.11* | 0.14* | 0.15* | 0.27** | 1 |

- Note: Gender is dummy coded: 0 = male; 1 = female.

- Abbreviations: CPST, Creative Problem Solving Test; TCT–DP, Test for Creative Thinking–Drawing Production; WKCT, Wallach-Kogan Creativity Test.

- ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

3.2 Mediation Analyses

3.2.1 Total Effects

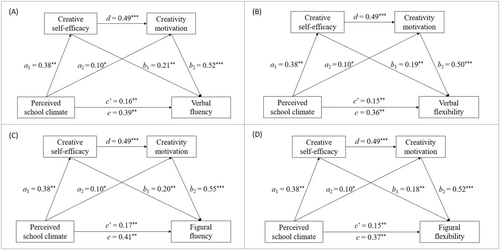

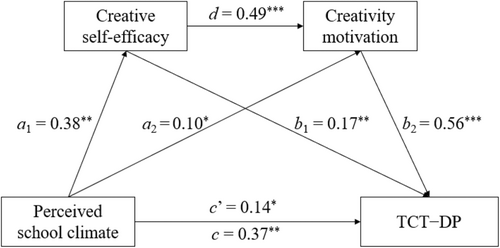

Figures 2-4 display the standardized coefficients of the multiple regression analyses regarding the direct paths among the study variables. The coefficient results reveal that perceived school climate had a significant total effect (c) on all three aspects of creativity performance, including the four indices of idea generation as measured by the WKCT (c = 0.36–0.41; all p values < 0.01; Figure 2), creative combinatory ability as measured by the TCT – DP (c = 0.37, p < 0.01; Figure 3), and restructuring ability as measured by the CPST (c = 0.37, p < 0.01; Figure 4).

3.2.2 Direct Effects

Statistical significance was also found for the direct effects of perceived school climate on all three aspects of creativity performance, as shown in Figures 2-4. Specifically, a significant direct effect c' = 0.15–0.17, c' = 0.14, and c' = 0.12–0.13 was found for the four indices of idea generation, creative combinatory ability, and restructuring ability, respectively (all p values < 0.05). With respect to the direct effects of perceived school climate on the two mediators, statistical significance was found for the paths from perceived school climate to creative self-efficacy (mediator 1; a1 = 0.38, p < 0.01) and creativity motivation (mediator 2; a2 = 0.10, p < 0.05) in all the models. Additionally, a statistically significant relationship was found for the path between the two mediators from creative self-efficacy to creativity motivation (d = 0.49, p < 0.001). With respect to the paths from the two mediators to creativity performance, statistical significance was found for the paths from creative self-efficacy (mediator 1; b1 = 0.18–0.21, p values < 0.001) and from creativity motivation (mediator 2; b2 = 0.50–0.55, p values < 0.001) to all four indices of divergent thinking. Moreover, statistical significance was also found for the paths from creative self-efficacy (b1 = 0.17, p < 0.01) and from creativity motivation (b2 = 0.56, p < 0.001) to creative combination. Additionally, for creative problem solving, statistical significance was found for the paths from creative self-efficacy (b1 = 0.14–0.15, p values < 0.05) and from creativity motivation (b2 = 0.46–0.48, p values < 0.001) to both verbal and figural creative problem solving.

3.2.3 Indirect Effects

The results of the indirect effects are summarized in Tables 4 and 6. As shown in Table 4, the indirect effects of perceived school climate on the four indices of divergent thinking through the first mediator (i.e., creative self-efficacy; a1 × b1) were statistically significant (β = 0.07–0.08, SE = 0.06–0.09; all 95% CIs did not include 0). Moreover, the indirect effects through the second mediator (i.e., creativity motivation; a2 × b2) also showed statistical significance (β = 0.05–0.06, SE = 0.01–0.03; all 95% CIs did not include 0). Furthermore, the indirect effects through the chain mediating effect of creative self-efficacy and creativity motivation (i.e., a2 × d × b2; β = 0.09–0.10, SE = 0.02–0.07, all 95% CIs did not include 0) also showed statistical significance. The percentages of the total indirect effects mediated by the two mediators were 59.0%, 58.3%, 58.5%, and 59.5% for verbal fluency, verbal flexibility, figural fluency, and figural flexibility, respectively. These results support Hypothesis 1.

| Effect | Pathway | Bootstrap estimate | 95% CI | PM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | LL | UL | |||

| Total IE | IE1 + IE2 + IE3 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.41 | 59.0% |

| IE1 | PSC → Creative self-efficacy → Verbal fluency (a1 × b1) | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 20.5% |

| IE2 | PSC → Creativity motivation → Verbal fluency (a2 × b2) | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 12.8% |

| IE3 | PSC → Creative self-efficacy & Creativity motivation → Verbal fluency (a2 × d × b2) | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.28 | 25.6% |

| Total IE | IE1 + IE2 + IE3 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.39 | 58.3% |

| IE1 | PSC → Creative self-efficacy → Verbal flexibility (a1 × b1) | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 19.4% |

| IE2 | PSC → Creativity motivation → Verbal flexibility (a2 × b2) | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 13.9% |

| IE3 | PSC → Creative self-efficacy & Creativity motivation → Verbal flexibility (a2 × d × b2) | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 25.0% |

| Total IE | IE1 + IE2 + IE3 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.44 | 58.5% |

| IE1 | PSC → Creative self-efficacy → Figural fluency (a1 × b1) | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 19.5% |

| IE2 | PSC → Creativity motivation → Figural fluency (a2 × b2) | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 14.6% |

| IE3 | PSC → Creative self-efficacy & Creativity motivation → Figural fluency (a2 × d × b2) | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.29 | 24.4% |

| Total IE | IE1 + IE2 + IE3 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.50 | 59.5% |

| IE1 | PSC → Creative self-efficacy → Figural flexibility (a1 × b1) | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 18.9% |

| IE2 | PSC → Creativity motivation → Figural flexibility (a2 × b2) | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 13.5% |

| IE3 | PSC → Creative self-efficacy & Creativity motivation → Figural flexibility (a2 × d × b2) | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 27.0% |

- Abbreviations: IE, indirect effect; PM, proportion of the total effect accounted; PSC, perceived school climate; WKCT, Wallach-Kogan Creativity Test.

As shown in Table 5, the indirect effect was statistically significant from the perceived school climate to the TCT–DP score through the first mediator (creative self-efficacy, β = 0.06, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.03, 0.26]) and through the second mediator (creativity motivation, β = 0.06; SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.01, 0.17]). Moreover, the indirect effect through the sequential mediating effect of the two mediators (β = 0.10; SE = 0.07, 95% CI [0.02, 0.21]) was also significant. The percentage of the total indirect effect mediated by the two mediators was 59.5%. These results support Hypothesis 2.

| Effect | Pathway | Bootstrap estimate | 95% CI | PM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | LL | UL | |||

| Total IE | IE1 + IE2 + IE3 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.36 | 59.5% |

| IE1 | PSC → Creative self-efficacy → TCT − DP (a1 × b1) | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 16.2% |

| IE2 | PSC → Creativity motivation → TCT − DP (a2 × b2) | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 16.2% |

| IE3 | PSC → Creative self-efficacy & Creativity motivation → TCT − DP (a2 × d × b2) | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 27.0% |

- Abbreviations: IE, indirect effect; PM, proportion of the total effect accounted; PSC, perceived school climate; TCT–DP, Test for Creative Thinking–Drawing Production.

As shown in Table 6, the indirect effects of perceived school climate on both the verbal (β = 0.06, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.01, 0.20]) and figural CPST scores (β = 0.05, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.02, 0.21]) through the first mediator (i.e., creative self-efficacy) were statistically significant. Moreover, the indirect effects through the second mediator (i.e., creativity motivation) also showed statistical significance for both the verbal (β = 0.05, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.01, 0.15]) and figural (β = 0.05, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.01, 0.18]) components. Furthermore, the indirect effects through the serial mediating effect of the two mediators (β = 0.09, all 95% CIs did not include 0) also showed statistical significance. The two mediators accounted for 60.6% and 61.3% of the total effect of perceived school climate on the verbal and figural CPST scores, respectively. These results support Hypothesis 3.

| Effect | Pathway | Bootstrap estimate | 95% CI | PM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | LL | UL | |||

| Total IE | IE1 + IE2 + IE3 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.39 | 60.6% |

| IE1 | PSC → Creative self-efficacy → Verbal CPS (a1 × b1) | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 18.2% |

| IE2 | PSC → Creativity motivation → Verbal CPS (a2 × b2) | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 15.2% |

| IE3 | PSC → Creative self-efficacy & Creativity motivation → Verbal CPS (a2 × d × b2) | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 27.3% |

| Total IE | IE1 + IE2 + IE3 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.32 | 61.3% |

| IE1 | PSC → Creative self-efficacy → Figural CPS (a1 × b1) | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 16.1% |

| IE2 | PSC → Creativity motivation → Figural CPS (a2 × b2) | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 16.1% |

| IE3 | PSC → Creative self-efficacy & Creativity motivation → Figural CPS (a2 × d × b2) | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 29.0% |

- Abbreviations: CPS, Creative Problem Solving; CPST, Creative Problem-Solving Test; IE, indirect effect; PM, proportion of the total effect accounted.

4 Discussion

4.1 Theoretical Significance

The findings of this study support Bandura's (1997) social cognitive theory by demonstrating how students' perceived school climate influences creativity through two psychological mechanisms—creative self-efficacy and creativity motivation—and through multiple pathways. Our study builds on previous works by Zhang et al. (2020) and Liang et al. (2023), who reported that self-efficacy and task motivation are crucial mediators in linking antecedent factors and creative behaviors. Our research further advances these previous works by building on social cognitive theory and explicitly integrating these mediators within one serial multiple mediation model, thus providing a more refined understanding of how these factors operate in sequence to influence creative outcomes. Despite the explicit theoretical argument of social cognitive theory with respect to the chain mediating effect of self-efficacy and task motivation in linking antecedent factors and functioning outcomes, previous research has often treated self-efficacy and task motivation as separate constructs. Our findings fill this theoretical gap by finding empirical evidence that these two constructs function synergistically in executing their mediating roles: while creative self-efficacy acts as the primary mediator in the pathway of transforming the students' perceived school climate to creativity performance, creativity motivation acts as a subsequent mediator to energize and sustain the effect of self-efficacy in executing its role in the mediation pathway.

More interestingly, by investigating the mediating effects of both creative self-efficacy and creativity motivation in one comprehensive model, our study illustrates that creative self-efficacy and creativity motivation can significantly mediate the effect of perceived school climate on three aspects of creativity performance as single and serial mediators. In general, the first mediator (creative self-efficacy) tends to have a slightly stronger effect than the second mediator (creativity motivation) in the mediation pathway across the three aspects of creativity performance. While the former was able to account for 16.2%–20.5% of the total mediation effect, the latter accounted for 12.8%–16.2%. These results suggest that creative self-efficacy plays a relatively primary role in the mediation pathways, which aligns with Tierney and Farmer's (2002) argument that self-efficacy is a key determinant of creative engagement and achievement. Our findings echo those of He (2023b) and He and Wong (2021a), who argued that creative self-efficacy is fundamental for initiating and maintaining creative effort. Enriching this line of research, the sequential mediation model employed in this study provides new insights by showing that creative self-efficacy not only fosters creativity directly but also enhances creativity motivation, which in turn promotes creative output. In fact, these findings regarding the subsequent effect of creativity motivation also align with many theories on creativity (e.g., componential theories of creativity, systems models of creativity) that highlight the critical role of tasks as essential engines in driving creative behaviors and sustaining creative efforts (Amabile 2011; Csikszentmihalyi 2015; Runco 2024). In short, the sequential mediating effect of creative self-efficacy and creativity motivation thus integrates these two perspectives, contributing to a more nuanced understanding of how the perceived school climate fosters creativity by shaping students' psychological resources.

Furthermore, by employing validated and multidimensional measures of creativity—such as a divergent thinking test, a gestalt combination test, and a creative problem-solving test—this study makes additional contributions to the ongoing debate about how creativity should be assessed in both research and interventions on creativity (Runco 2024; Sternberg et al. 2024). Prior studies have often relied on a singular measure of creativity, typically divergent thinking (Runco and Acar 2012). Our approach is more comprehensive, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of how the perceived school climate operates through creative self-efficacy and motivation to influence different dimensions of creativity performance. This approach also provides valuable insights into potential interventions aimed at fostering students' creative potential in school contexts. Given the broad conceptualization of creativity as a multifaceted construct (Beghetto and Karwowski 2023), our findings contribute to theoretical models in education (He 2023a, 2023b, 2024).

4.2 Practical Significance

The practical implications of this study highlight several actionable recommendations for educators, policymakers, and practitioners. First, the findings suggest that the perceived school climate indirectly influences creativity by increasing the creative self-efficacy and creativity motivation of students. This finding reinforces the importance of creating an environment where students feel supported in taking creative initiatives, as noted by Amabile (2018) and Steele et al. (2017), who reported that supportive environments are crucial for fostering creative behaviors. Our study extends this idea by identifying creative self-efficacy and creativity motivation as key mediators through which the perceived school climate influences creativity. This finding indicates that schools should prioritize initiatives that enhance the self-belief and self-confidence of students in their creative potential, as well as the task motivation in creative intervention programs such as creativity workshops, mentorship programs, and problem-based learning activities, which can foster both creative self-efficacy and creativity motivation. This finding is consistent with the work of Beghetto and Karwowski (2023), who emphasized the need for interventions targeting creative self-efficacy to foster creativity. More importantly, our study highlights the sequential relationship between creative self-efficacy and creativity motivation, suggesting that interventions aimed solely at improving self-efficacy may not be sufficient unless they also address task motivation; this adds a layer of complexity to the design of creativity-enhancing interventions, suggesting that both self-efficacy and motivation must be nurtured in tandem to achieve lasting creative engagement.

Moreover, this study supports the value of employing multidimensional creativity assessments in educational settings. This recommendation is in line with recent work by Runco (2024), who advocates for a broader approach to evaluating creativity that goes beyond divergent thinking tests. The use of the WKCT (a divergent thinking test), the TCT–DP (a gestalt combinatory test), and the CPST (a creative problem-solving test) in our study provides a reliable framework for assessing creativity across multiple domains. These tools allow educators to obtain a more holistic and concise understanding of the creative profiles of students, including both strengths and weaknesses, which can in turn inform the design of more personalized and effective interventions. Furthermore, the sequential relationship between creative self-efficacy and creativity motivation suggests that creative development should be embedded within educational practices that recognize the dynamic interplay between self-efficacy and motivation rather than relying on isolated or short-term interventions. Our results indicate that schools should integrate creative training into the curriculum, promote extracurricular activities, and provide continuous support that fosters both self-belief and intrinsic motivation in creativity. This approach equips schools with strategies to cultivate a supportive environment that nurtures both self-belief and intrinsic motivation, ensuring the long-term sustainability of initiatives towards the development of creativity.

4.3 Limitations and Future Directions of Research

We note several limitations that suggest directions for future research. First, the cross-sectional design restricts causal inferences. Although mediation analysis supports theoretical assumptions about the sequential relationships among perceived school climate, creative self-efficacy, creativity motivation, and creativity performance, longitudinal or experimental studies are necessary to confirm the directionality and stability of these relationships over time (He and Wong 2021a; Liang et al. 2023). Second, the sample, comprising Chinese secondary school students, limits the generalizability of the findings to other cultural and educational contexts. Cultural factors, such as collectivism and conformity in Chinese education, may uniquely influence the observed relationships (He 2023a; Zhang et al. 2020). Testing the model in diverse cultural settings, such as individualistic contexts, can reveal whether similar pathways operate across varying cultural values. Cross-cultural studies could also explore how educational practices interact with the school climate to shape the development of creativity. Moreover, the use of a convenience sampling method, while practical, may limit the broader applicability of the findings. Although the selected schools represent a range of districts, the sample may not fully capture the diversity of secondary school students in Hong Kong. Future research could employ random or stratified sampling methods to increase the generalizability of the results.

Third, while this study focuses on individual student perceptions of the school climate, it does not account for the broader collective or institutional perspective. Given that the school climate can also be understood as a shared experience among students, teachers, and administrators, future studies could expand the scope by incorporating multiple perspectives to achieve a more holistic understanding (Bottiani et al. 2020). Moreover, the reliance on self-reported data introduces methodological challenges, as different school climate measurement tools vary in their focus, content coverage, and psychometric properties (Marraccini et al. 2020). Ensuring consistency in measurement approaches and considering complementary data sources, such as teacher and peer assessments, could enhance the validity of school climate evaluations. Additionally, one limitation of this study is the use of an overall mean score to measure perceived school climate rather than analyzing its distinct dimensions separately. While this approach aligns with prior research (Zhang and Wang 2020), Way et al. (2007) emphasized that teacher support, peer support, student autonomy, and clarity and consistency in school rules, though interconnected, should be treated as separate constructs. Future studies could adopt a multidimensional approach to better capture the unique contributions of each school climate component to creativity and other student outcomes. There is some debate regarding whether the TCT–DP effectively measures creative combinatory ability or if it primarily assesses creativity in figural material, focusing on visual and structural transformations (Plucker et al. 2010). Although the TCT–DP has been highlighted for its effective use in assessing creative combinatory ability (Haase et al. 2018; He 2023a), future research could explore additional assessments to better differentiate creative combinatory ability from broader aspects of both verbal and figural creativity.

Fourth, the study did not examine moderating factors, such as individual traits (e.g., personality and prior creative experience) or environmental influences (e.g., parental involvement and peer support), that might affect the observed relationships among the school climate, psychological mediators, and creativity outcomes (Martinsone et al. 2023; Huang 2023). Investigating these factors would provide a more nuanced understanding of the mechanisms influencing creativity. Fifth, while the multiple-measurement approach captures idea generation, creative combinatory ability, and restructuring ability, these instruments may not fully reflect real-world creativity or domain-specific applications (Runco 2024; Sternberg et al. 2024). Future research could employ authentic assessments, such as project-based evaluations, to better represent creativity performance in practical settings. Finally, although the findings emphasize the importance of creative self-efficacy and creativity motivation, the model excludes other relevant psychological factors. For example, creative metacognition, which involves the awareness and regulation of one's creative processes, is a promising variable for future exploration (He and Wong 2022a; Liang et al. 2023). Additionally, examining the impact of external factors, such as teacher training or institutional policies, could further enrich the understanding of how the school climate fosters creativity. In summary, addressing these limitations through longitudinal, cross-cultural, and multidimensional research designs will deepen the understanding of the role of the school climate in creativity and expand the theoretical and practical contributions of the results.

5 Conclusion

This study underscores the transformative potential of the school climate in shaping student creativity, offering a nuanced understanding of the psychological pathways that translate supportive environments into creative outcomes. By situating creative self-efficacy and creativity motivation within a serial mediation framework, this study bridges research gaps in social cognitive theory and highlights the intricate interplay between cognitive and motivational processes in fostering creativity. In addition to theoretical validation, the findings challenge educators and policymakers to rethink the design of educational environments. Emphasizing self-belief as the cornerstone of creative engagement and motivation as the engine to energize the expression, actualization, and continuation of the self-efficacy effect, this study advocates practices that inspire self-confidence and intrinsic motivation in students. The multidimensional assessment approach used in this study enriches research on creativity by capturing the diverse facets of creative expression and paving the way for innovative educational tools and policies. As creativity becomes an increasingly essential skill in a rapidly changing world, this research lays a foundational framework for future exploration. Expanding beyond cultural and methodological constraints will be critical to fully realizing the global applicability and transformative impact of fostering creativity in education.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.