The missing link? Implications of internal, external, and relational attribution combinations for leader–member exchange, relationship work, self-work, and conflict

Summary

Attributions are causal explanations made by individuals in response to important, novel, and/or unexpected events. Numerous attribution theories have examined how people use information to make attributions and how attributions impact an individual's subsequent emotions and outcomes. However, this research has only recently considered the implications of dyadic-level attributions (i.e., relational attributions), particularly in the context of leader–follower relationships in organizations. Therefore, the purpose of this theoretical paper is threefold. First, we integrate research on attributional biases into the research on relational attributions. Second, we integrate and extend attribution theory to consider the implications of convergent and divergent internal, external-person, external-situational, and relational attributions for leader–member exchange (LMX) quality, relationship work, self-work, and conflict. Third, we make the implicit ranking of attribution combinations and the resultant levels of relationship work explicit. In doing so, we contribute to attribution theory and research by proposing how attribution combinations produce positive and negative outcomes that are both intrapersonal and interpersonal. Further, we contribute to the LMX literature by explicating how leader–follower attribution combinations influence relationship quality.

1 INTRODUCTION

“Naive psychology”; Heider (1958), the founder of attribution theory, used this term to convey his assertion that humans have an innate desire to attribute causes to events (p. 5). When making such attributions, Heider posited that people make a fundamental distinction between internal and external causes for events that occur. By definition, internal attributions (e.g., ability and effort) arise from the focal actor, whereas external attributions emanate from the situation (e.g., luck and task difficulty; external-situational attributions) or other parties (external-person attributions). Throughout the rich history of attribution theory (e.g., Martinko, 1995, 2004), these two poles of the locus of causality dimension—internal and external—have remained at its core.

Recently, Eberly, Holley, Johnson, and Mitchell (2011) proposed a refinement to attribution theory by introducing a third category of locus of causality attributions that pertains to the dyadic level of analysis: relational attributions. Specifically, they argued that people in relationships sometimes attribute the cause of an event to the relationship with the other person (i.e., “something about us”; a relational attribution) rather than to purely internal or external sources. They defined relational attributions as “those explanations made by a focal individual that locate the cause of an event within the relationship that the individual has with another person” (p. 736). They also suggested that when relational attributions are made, the parties are more likely to engage in relationship-focused behaviors, or relationship work. In subsequent empirical research using data from seven samples, the authors tested and found support for the existence of relational attributions that are distinct from internal and external attributions, and they found that relational attributions are related to relationship work (Eberly, Holley, Johnson, & Mitchell, 2017).

In considering the implications of relational attributions, Eberly et al. (2011) presented arguments for how attributions can prompt individuals to make personal changes (i.e., enhance skills), situational changes (i.e., change jobs), or relationship changes (relationship work). These adaptive behaviors are suggested to result from internal, external, and relational attributions, respectively. The theoretical arguments, however, have yet to consider how an individual's attributional biases impact the type of attribution that is made. The exclusion of biases from relational attribution theorizing is noteworthy because biases have the potential to significantly impact an individual's perception of an event. Moreover, “biases in the attribution process may be an important source of perceptual conflict between leaders and members” (Martinko & Gardner, 1987, p. 239). Therefore, our first purpose is to integrate attributional bias and relational attribution theory.

In addition, relational attribution theory has not explored how leader–follower attribution combinations may have implications for relationship work as well as other important outcomes. The relationship between leaders and followers is often one of the strongest connections between employees (Hui, Lee, & Rousseau, 2004). These relationships are commonly characterized by a high degree of interaction and task dependence along with expansive time bracketing—a history of past interactions and an expectation of future exchanges (Colquitt et al., 2013). Therefore, unexpected and negative events are likely to prompt a search for causes by both the leader and follower in this important organizational relationship, and in response to the resultant attributions, emotions and behaviors of both parties are likely to be provoked. Attribution theory has long established the link between emotion and behavior (Weiner, 1985), and prior theoretical research has explored leader–follower attribution responses (e.g., Martinko & Gardner, 1987). However, what is missing is a comprehensive consideration of the responses to leader–follower attribution combinations that may be either convergent (i.e., the leader and follower make the same attribution for the event) or divergent (i.e., the leader and follower make different attributions for the event). Therefore, our second purpose is to integrate and extend the theory by Martinko and Gardner (1987) and Eberly et al. (2011) to consider the implications of convergent and divergent internal, external-person, external-situational, and relational attributions for leader–member exchange (LMX) quality, relationship work, self-work, and conflict. In addition, we make the implicit ranking of attribution combinations and the resultant levels of relationship work explicit. We believe that examining these attribution combinations may provide the “missing link” for better understanding both intrapersonal and interpersonal leader–follower outcomes.

Thus, the manuscript proceeds as follows. First, we provide an overview of attribution theories and LMX theory. Next, we present a model of leader and follower attributional biases, attribution combinations, LMX quality, relationship work, self-work, and conflict. We proceed by integrating the work of Martinko and Gardner (1987) and Eberly et al. (2011) to discuss the implications of leader and follower attribution combinations for these outcomes. Then, we discuss the interaction of attribution combinations and LMX quality to describe how LMX quality impacts the likelihood of relationship work and conflict. Finally, we discuss theoretical and practical implications of the propositions as well as areas for future research.

2 THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS

2.1 Attribution theories

“Attributions are the causal explanations that individuals use to interpret the world around them and adapt to their environment,” especially when attempting to understand events that are important, novel, unexpected, and negative (Eberly et al., 2011, p. 733). Scholars have remarked that “there is no ‘attribution theory’ … [rather] the term attribution theories applies to a broad group of theories that are concerned with causal reasoning” (Martinko & Thomson, 1998, p. 272). Attribution theories, therefore, focus on the processes through which people attempt to explain the causes of behaviors or events (Harvey, Madison, Martinko, Crook, & Crook, 2014; Heider, 1958; Kelley, 1967, 1973; Martinko, Harvey, & Dasborough, 2011; Weiner, 1985). Numerous scholars have extended Heider's (1958) initial work on attributions. Below, we describe several attribution theories that are most relevant to our model.

Kelley (1967, 1973) introduced the covariation model to describe how people make attributions using informational cues across multiple observations. He suggested that individuals consider three information criteria—distinctiveness, consistency, and consensus—related to a behavior or event when making attributions. Distinctiveness information involves within-person behavior that “compares the behaviors of the individual in other situations” (Martinko & Thomson, 1998, p. 273). Consistency information also involves within-person information, but it incorporates a longitudinal perspective that considers whether the behavior is similar or different across time (Kelley, 1973; Martinko & Thomson, 1998). Consensus information assesses whether behavior is common across individuals in similar situations; that is, it is a between-person appraisal that compares the focal party's behavior with the behavior of others (Harvey et al., 2014; Kelley, 1973). When consensus is high, it generally leads to an internal locus of causality, whereas low consensus information leads to an external locus of causality. When combined, Kelley's three informational criteria form patterns that individuals use to attribute causes to specific behaviors or events. Ability attributions generally occur when there is information that is high on distinctiveness, high in consistency, and low on consensus. Attributions related to a person's effort are likely when information is low on consensus, low on consistency, and high on distinctiveness. High consensus information leads to an external locus of causality. Information about the target that is high in consensus, consistency, and distinctiveness will likely result in attributing the outcome to the nature if the task. An outcome that is high on consensus and low in both consistency and distinctiveness will likely be attributed to luck. Thus, the consensus information affects locus of causality, and both distinctiveness and consistency information allow more nuanced attributions that go beyond the internal and external dimensions.

Whereas Kelley's (1973) covariation model focuses on how information is used to make attributions, Weiner's (1985) extensions to attribution theory emphasized three causal dimensions (i.e., the causal structure) and, importantly, the emotional and behavioral outcomes of attributions (i.e., the achievement motivation model). Weiner contends that the causal dimensions of attributions are locus of causality, stability, and controllability. Locus of causality “describes the extent to which an event is attributed to causes internal or external to the observer” (Harvey, Martinko, & Borkowski, 2017, p. 781). Stability refers to the extent to which an observed event is enduring (i.e., permanent) or temporary (i.e., variable), and controllability describes the event cause as one that is either “volitional or optional control” or uncontrollable (Weiner, 1985, p. 551). Weiner goes on to establish how the causal structure of attributions influences emotions and behavior. Emotional responses can include anger or frustration, commonly caused by external attributions, and guilt, commonly caused by internal attributions (Weiner, 1985, 1986). Behavioral reactions may consist of helping behaviors (Weiner, 1985, 1986), task performance (Thomas & Mathieu, 1994), and even deviant behaviors (Harvey et al., 2017). The achievement motivation model “therefore relates the structure of thinking to the dynamics of feeling and action” (Weiner, 1985, p. 548).

An important distinction between Kelley's and Weiner's research is the emphasis on intrapersonal or social attributions. That is, Kelley's (1967, 1973) covariation model primarily focused on providing explanations for social attributions (i.e., attributions for others), whereas Weiner's (1985) achievement motivation model primarily emphasized how individuals make intrapersonal (i.e., self) attributions. Given the scope of these different models, Martinko and Thomson (1998) integrated Kelley's and Weiner's research by noting a direct relationship between the consistency and consensus informational cues introduced by Kelley (1967) and Weiner's (1985) attributional dimensions of locus of causality and stability. They proposed a direct relationship between Kelley's consistency information and Weiner's stability dimension by arguing that within-person, consistent information is indicative of a stable attribution. In addition, they suggested that Kelley's consensus informational cues and Weiner's locus of causality dimension are related by noting that behaviors or events “high in consensus are attributed to the characteristics of the situation (i.e., external) and outcomes that are low in consensus are attributed to the internal characteristics of the actor” (p. 276). The integration of these models was an important contribution for the application of attribution theories to a range of contexts, including the leader–follower relationship in organizations.

In research aimed at specifically exploring attributions in leader–follower dyads, Martinko and Gardner (1987) built on this prior research to discuss combinations of leader and follower internal and external attributions. In their model, the leader first makes an attribution based on the follower's task-directed behavior. Then, on the basis of the leader's attribution and response, they suggested various ensuing member attributions and responses including helplessness, performance deficits, and conflict. Another important contribution of this theory was the integration with the literature on attributional biases. They suggested that followers will be more likely to attribute their own failure to external causes whereas leaders will be more likely to blame follower characteristics. Therefore, they argued that divergent attributions for follower failure will likely result in conflict.

More recently, Eberly et al. (2011) considered dyadic relationships in organizations to extend the theoretical research on attribution theory through the introduction of a third locus of causality category, relational attributions. In developing the theory of relational attributions, the authors advanced propositions to explain how the distinctiveness, consistency, and consensus information cues specified by Kelley (1973) elicit relational attributions at the dyadic level. Note that because negative achievement-related events are more likely to elicit attributional processing than are positive events (Martinko, Harvey, & Douglas, 2007; Weiner, 1990), Eberly et al. (2011) confined their model to attributions for the former. They also emphasized that relational attributions are based on high distinctiveness, high consistency, and low consensus information from a negative achievement-related event. For example, in the context of a leader–follower dyad, a follower who is not selected by her or his leader for an important client team may consider that (a) she or he had routinely been selected for important client teams by other supervisors (high distinctiveness); (b) she or he had yet to be selected for an important client team by this supervisor (high consistency); and (c) the majority of her or his colleagues were selected to be a part of this important client team (low consensus). With this information, the follower is likely to make a relational attribution. If we again consider the context of a leader–follower dyad, another example would be where a leader struggles to motivate a follower to achieve his or her goals. The leader may consider that (a) he or she has never struggled to motivate other followers (high distinctiveness); (b) he or she has struggled for several performance review cycles to motivate this follower (high consistency); and (c) other leaders have followers that respond positively to the motivation techniques that he or she employed (low consensus). Here again, with this information, the leader is likely to make a relational attribution.

Eberly et al. (2011) also asserted that relational attributions are more likely to prompt individuals to proactively repair their relationship by engaging in relationship work. Namely, relational attributions based on high distinctiveness, high consistency, and low consensus informational cues focus dyadic partners on addressing the relational causes of negative events and prompt individuals to engage in relationship work such as remedial voice behaviors (e.g., discussing the issue) or interpersonal citizenship behaviors (e.g., providing assistance with tasks or socioemotional support). In subsequent empirical research, Eberly et al. (2017) found that individuals spontaneously make internal, external, and relational attributions, and they discussed how leader–member interdependence increases the likelihood of a relational attribution. Additional empirical work has supported relational attribution theorizing and has examined the implications of relational attributions in the context of abusive supervision. Burton, Taylor, and Barber (2014) found that relational attributions for the behavior of abusive supervisors are likely when the subordinate believes he or she has not been treated this way by previous supervisors (high distinctiveness), the subordinate believes the abuse is happening frequently (high consistency), and the subordinate believes that the supervisor is not treating anyone else in the same way (low consensus).

Despite these advances in attribution theories and relational attribution research, there is still an incomplete understanding of how attribution combinations affect LMX quality. Therefore, we next provide an overview of LMX theory.

2.2 LMX theory

LMX theory focuses on the dyadic relationships between leaders and followers whereby relationships develop with varying levels of affect, loyalty, contribution to the relationship, and professional respect (Dienesch & Liden, 1986; Graen & Cashman, 1975; Graen & Scandura, 1987; Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995; Liden & Maslyn, 1998). Followers with high-quality LMX relationships receive more information and attention, have greater influence, and experience more beneficial work outcomes than do followers in low-quality LMX relationships whose exchanges are more transactional and linked to formal job requirements (Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer, & Ferris, 2012). Leaders in high-quality LMX relationships, on the other hand, enjoy relationships of high trust in members where they can delegate important work to members and have confidence it will be done well and on time, rely on members to look out for their best interests, and enjoy the satisfaction of providing support and in many cases mentorship to the member. In contrast, leaders in low-quality LMX relationships may become frustrated by a perceived lack of commitment from the member and an overall lack of trust that the member will perform work assignments well and look out for the leader's interests (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995; Liden, Sparrowe, & Wayne, 1997). Thus, high-quality LMX relationships are characterized by interdependent interactions that are mutually beneficial and focused on the long term, and low-quality LMX relationships are exemplified by high self-interest and immediacy and equivalence in exchange transactions (Uhl-Bien & Maslyn, 2003).

LMX quality is most commonly assessed from solely the follower's perception of the relationship, yet when it is also measured from the leader's perspective, there is often disagreement between the parties. Indeed, meta-analytic evidence indicates that the correlation between leader and follower reports of LMX is .29 (Gerstner & Day, 1997), and research has demonstrated that followers may overestimate the quality of the relationship, failing to recognize that the leader does not judge it to be equally beneficial (Cogliser, Schriesheim, Scandura, & Gardner, 2009). Such overestimation is associated with lower levels of leader-rated member job performance than is the case in balanced high-quality LMX relationships where both parties view the relationship positively. However, conceptually, LMX is a dyadic-level theory, and its measurement should include both leader and follower perceptions of relationship quality as both the leader and the follower must devote effort into the relationship for a high-quality relationship to develop (Maslyn & Uhl-Bien, 2001).

Why might individuals exert this effort? According to Martinko, Moss, Douglas, and Borkowski (2007), leader and follower attributions have a profound effect on the quality of LMX; therefore, the nature of the causal attributions they make for an important, novel, unexpected, and/or negative event is likely to influence the amount of relationship work by both the leader and the follower. As Eberly et al. (2011) suggested, when leaders and/or followers make relational attributions, they direct attention toward relational influences on events rather than on purely internal or external causes. That is, when leaders and followers make relational instead of purely internal or external attributions about events, they will subsequently either expend effort toward, or withhold effort from, the relationship, thereby causing increases or decreases to relationship quality. However, given the research on LMX agreement cited above, we contend that it is likely that leader and follower internal, external, and relational attribution combinations will frequently diverge. Thus, we present a model of attribution combinations, LMX quality, relationship work, self-work, and conflict, which considers the implications of convergent and divergent leader–follower attributions.

Before we elaborate on the elements of our proposed model and the associated propositions, we first follow Bacharach's (1989) recommendations for theory building by specifying the model's underlying assumptions and boundary conditions.

2.3 Underlying assumptions and boundary conditions

First, we recognize that attribution processes can be triggered by either positive or negative events. Nonetheless, as noted above, we follow the conceptual foundation of Eberly et al. (2011) and focus exclusively on negative achievement-related events in our model because they are more likely to “threaten goal accomplishment and motivate people to find underlying causes so they can avoid similar events in the future” (p. 735). This is consistent with prior research that asserts that not every event triggers attribution processes—they are most common when the event is important, surprising, and/or negative (Eberly et al., 2011; Weiner, 1986). Moreover, it is certainly possible that events may not trigger relationship work but instead cause the leader and/or follower to withdraw from the relationship (Eberly et al., 2011), become hostile or resentful (Ferris et al., 2009), or engage in avoidant or antisocial behaviors (Stafford & Canary, 1991). These reactions are also outside the scope of our model but warrant additional attention in future research.

Next, we note that both relational attribution theory and LMX theory are dyadic in nature. Therefore, we limit the focus of our model to the hierarchical relationship between a leader and a follower. Given this dyadic emphasis, we are focused on dyadic-level theory, analysis, and measurement. For example, when we discuss LMX quality, we are specifically referring to leader–member dyads with high agreement on LMX quality (i.e., both the leader and the member agree that the relationship quality is high or low). Moreover, we acknowledge that there are likely to be differential amounts of effort expended by the leader and follower to enhance LMX quality following a negative and/or unexpected event, and there are likely to be differential effects on LMX quality based on each party's capabilities and availability for relationship work. Indeed, Eberly et al. (2017) found that time or availability was a significant contextual moderator of the relationship between relational attributions and relational improvement behaviors. However, these differences are beyond the scope of our model.

Further, we acknowledge that dyads are nested within collectives, and therefore, the locus of causality attributions may be made that consider relationships at a higher level of analysis beyond the dyad (e.g., groups and organizations) as potential causes. Here again, however, our focus is exclusively on the dyadic level, consistent with the dyadic focus of relational attribution (Eberly et al., 2011) and LMX (Liden et al., 1997) theories. Also, with regard to social exchange processes, we do not consider higher level collective constructs such as team member exchange (Seers, 1989; Seers, Petty, & Cashman, 1995).

Finally, there are numerous contextual factors that may affect the relationships presented in our model. These could include the leader's span of control; the extent of the leader's and follower's task interdependence; the type of leader and follower work; and the organization's structure (Rousseau & Fried, 2001). These are also important considerations for future research which are not discussed in this manuscript.

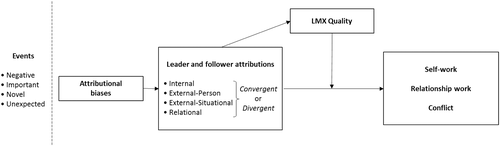

3 MODEL OF LEADER–FOLLOWER ATTRIBUTIONAL BIASES, ATTRIBUTION COMBINATIONS, LMX QUALITY, RELATIONSHIP WORK, SELF-WORK, AND CONFLICT

Because negative and unexpected events are more likely to be viewed as informative and provoke greater search for causes (Martinko et al., 2007; Weiner, 1985), as previously noted, our model begins with the leader and follower reflecting on a negative and/or unexpected achievement-related event and subsequently making attributions for the event (see Figure 1). We then extend Eberly et al.'s (2017) model by considering the influence of attributional biases on leader and follower attributions. We further integrate and extend Martinko and Gardner's (1987) and Eberly et al.'s (2017) models by considering the extent to which leader and follower attributions are convergent versus divergent when the dyadic partners make internal, external-person, external-situational, or relational attributions. Then, the model connects the attribution combinations to LMX quality, relationship work, self-work, and conflict. The model also depicts how LMX quality can moderate this process, with relationship work being more likely in high- as compared with low-quality relationships and with conflict being less likely in high- as compared with low-quality relationships.

Based on the aforementioned theoretical grounding, the model presented herein focuses on relationship work, self-work, and conflict as dependent variables elicited by convergent or divergent attribution combinations. Martinko and Gardner (1987) specifically proposed that the degree of convergence between leader and follower attributions is negatively related to leader–follower conflict. Accordingly, we suggest that specific combinations of divergent leader–follower attributions (described in greater detail below) will lead to conflict. In addition, Eberly et al. (2011) emphasized that relational attributions elicit relationship work, and they also acknowledged that individuals may make changes to their own behavior (i.e., self-work), particularly if one party to the dyad makes an internal attribution. Therefore, the dependent variables of our model reflect a range of positive and negative outcomes that are both intrapersonal and interpersonal. We discuss each of these dependent variables below.

Relationship work is relationship-focused behavior that is aimed at protecting or enhancing the quality of the relationship (Eberly et al., 2011). Given the importance of leader–follower relationships in organizations, leaders or followers feel “distress and anxiety at the prospect of a threatened relationship” and therefore engage in relationship work to return the relationship to a desired, stable state (Eberly et al., 2011, p. 741). Relationship work may consist of voice behaviors or interpersonal citizenship behaviors focused on either the task (i.e., helping complete a job and supplying information) or the person (i.e., demonstrating concern and offering counsel; Eberly et al., 2011). Additionally, relationship work may include activities aimed at enhancing cognitive aspects of the relationship such as improving or restoring commitment, respect, or trust in the relationship (Ferris et al., 2009).

We draw from the emerging literature on leader self-development (Orvis & Ratwani, 2010; Reichard & Johnson, 2011; Reichard, Walker, Putter, Middleton, & Johnson, 2017) and employee self-development (Orvis & Leffler, 2011) to introduce the concept of self-work as an intrapersonal analog to the interpersonal activities involved in relationship work. That is, we define self-work as intrapersonal and self-reflective efforts to improve one's task-related skills (e.g., technical skills and analytical skills) or personal abilities (e.g., communication skills, conflict resolution skills, and time management skills).

Conflict refers to “perceptions by the parties involved that they hold discrepant views” (Jehn, 1995, p. 257). It is the perception of disagreement between two interdependent parties that can be caused by a variety of factors including individual differences, communication, structure, and perceptions (Wall & Callister, 1995). For example, in prior theoretical research, Martinko and Gardner (1987) proposed that more versus less congruent leader–member attributions would be negatively related to conflict. For the purposes of our model, we identify the dyadic partner who is likely to initiate conflict in response to his or her attributions by distinguishing between follower-initiated and leader-initiated conflict. For example, if a follower does not receive adequate resources from the leader to accomplish a task on time, the follower may initiate conflict (i.e., follower-initiated conflict), or if a leader does not perceive adequate socioemotional support from the follower, the leader may initiate conflict (i.e., leader-initiated conflict). Note that in some cases the leader and follower may simultaneously initiate conflict as a result of their attributions, in which case we posit that mutually-initiated conflict will ensue.

3.1 Attributional biases

In attribution theory, there is an assumption that people use a naive version of the scientific method to make causal inferences. However, such inferences are subject to bias due to incomplete evidence and unknown or misleading contextual information (Kelley, 1973; Shaver, 1983); this is known as attributional bias. Although there are several types of attributional biases, we focus on two that are particularly salient within dyadic relationships: the self-serving bias and actor-observer bias.

The self-serving bias refers to the tendency for persons to attribute their successes to internal causes (effort, ability) while attributing their failures to external causes (Sedikides, Campbell, Reeder, & Elliot, 1998). The actor-observer bias involves a tendency for people to attribute their failures to external causes while attributing others' failures to internal causes (Jones & Nisbett, 1972; Ross, 1977). The implication for leaders and followers confronted with negative achievement-related events is that these biases will make external (person or situational) attributions more likely, and relational attributions less likely, because relational attributions partially implicate the attributor. For example, both of these biases would increase the likelihood that a leader who does not meet an important deadline (i.e., the negative event) attributes the cause to the follower's performance (i.e., external-person), rather than the relationship. Similarly, these biases would both increase the likelihood that a follower who fails a quality inspection (i.e., the negative event) will attribute the cause to the leader (i.e., external-person) or the situation (i.e., external-situational) rather than the relationship.

Proposition 1.As self-serving and actor-observer biases on the part of the leader and/or follower increase in intensity, the propensity to engage in relational attributions decreases.

4 LEADER–FOLLOWER ATTRIBUTION COMBINATIONS

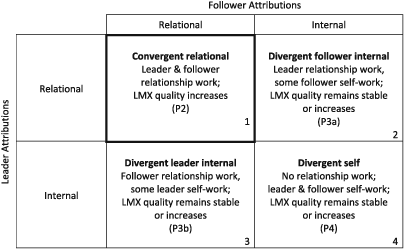

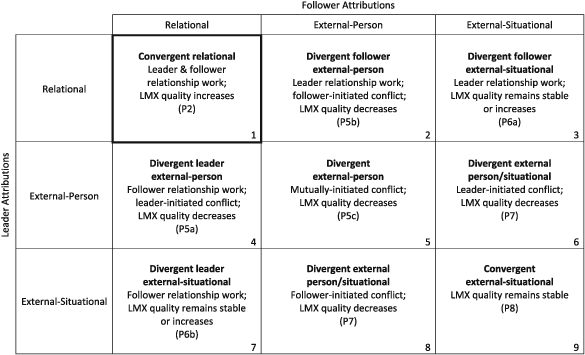

In this section, we consider the various combinations of relational, internal, and external attributions and the implications of these combinations for LMX quality, relationship work, self-work, and conflict. Consistent with prior theory (Heider, 1958), we distinguish between two types of external attributions: external-person and external-situational attributions. The former term refers to external attributions to the dyadic partner, and the latter indicates an external attribution to the situation. Note that because Martinko and Gardner (1987) previously discussed the relational implications of various combinations of leader and follower internal versus external attributions in detail, we do not consider the internal–external attribution combinations here. Instead, we focus exclusively on the theoretical implications of the various combinations of relational and internal attributions (Table 1), and relational, external-person, and external-situational attributions (Table 2), because these have not been heretofore examined.

|

- Note. We use the term convergent to indicate that the leader and follower make the same attribution for the event to the relationship (i.e., relational attributions). Divergent indicates that the parties make different attributions for the negative event to combinations of the relationship and themselves (i.e., leader/follower internal). The numbers located in the lower right corners of the cells are referred to in propositions throughout the manuscript. The bold line around Cell 1 indicates that convergent relational attributions appear in both Tables 1 and 2. P = proposition.

|

- Note. We use the term convergent to indicate that the leader and follower make the same attribution for the event to the relationship (i.e., relational attributions) or to the situation (i.e., external-situational attributions). Divergent indicates that the parties make different attributions for the event to combinations of the relationship, the situation, or the dyadic partner (i.e., leader/follower external person). The numbers located in the lower right corners of the cells are referred to in propositions throughout the manuscript. The bold line around Cell 1 indicates that convergent relational attributions appear in both Tables 1 and 2. P = proposition.

We use the term convergent to indicate that the leader and follower both attribute the negative event to the same cause. We use the term divergent to indicate that the parties make different attributions for the event. Given our focus on relational attributions, we adopted a convention whereby a relational attribution is assumed to be the default condition, and deviations from this default that reflect attributional disagreement are labeled as divergent attributions. Doing so allowed us to reflect through the labels used in the table cells cases where only one party made a non-relational attribution. Specifically, when one party makes a relational attribution and the other party makes an internal or external attribution, we identify the party making the non-relational (divergent) attribution in the cell label. Thus, for example, we use the term divergent follower internal attribution (Table 1, Cell 2) to indicate that the follower makes an internal (self) attribution that diverges from the leader's relational attribution. Similarly, we use the term divergent leader internal attribution (Table 1, Cell 3) to indicate that the leader makes an internal (self) attribution that diverges from the follower's relational attribution. However, for cases where both parties make non-relational attributions, we do not specify one party as the source of divergence, because such divergence from a relational attribution is mutual.

Note further that when both the leader and follower make internal attributions or external-person attributions, we label these as divergent rather than convergent attributions, because the parties disagree on the cause of the event, with each attributing it to themselves in the former case (Table 1, Cell 4: divergent self attributions), and the other person in the latter (Table 2, Cell 5: divergent external-person attributions). Finally, note that only two of the combinations we examine reflect convergence, where both parties agree on the event cause: convergent relational attributions (Tables 1 and 2, Cell 1) and convergent external-situational attributions (Table 2, Cell 9). In the former case, both the leader and follower attribute the event to the relationship; and in the latter, they both make an external attribution to the situation. Even though the attributions diverge from the default relational attribution in the latter case, we view them as convergent, because both parties agree that the situation is the cause of the event.

4.1 Convergent relational attributions

When both the leader and follower attribute a negative event (e.g., poor follower performance) to the relationship, the attributions converge (Tables 1 and 2, Cell 1: convergent relational attributions). Under these circumstances, relationship work by both the leader and follower is highly likely to occur, because both parties view some aspect of their relationship as causing the adverse event. When participants in a relationship make relational attributions, they both pay attention to the areas of the relationship that need improvement (Brewer & Gardner, 1996; Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Moreover, the leader and follower are both likely to experience feelings of guilt. Weiner (1986) considered guilt to be related to the controllability causal dimension, and he suggested that it commonly arises due to feelings of personal accountability (e.g., lack of effort). Therefore, in cases of convergent relational attributions for negative events, each party's guilt is likely to be directed toward effort to improve the relationship, and it will likely promote behaviors that address and provide retribution for the identified cause (Weiner, 1985). In subsequent research, Brees and Martinko (2015) elaborated on the connection between personal accountability and organizational citizenship behaviors. In other research, Harvey et al. (2017) described this as “adaptive guilt” because it prompts individuals to constructively address the adverse event to prevent it from happening again in the future (p. 783). In addition, the focus by both parties on improving the relationship is likely to increase LMX quality.

4.2 Divergent internal attributions

When either the leader makes a relational attribution and the follower makes an internal attribution (Table 1, Cell 2: divergent follower internal attributions) or vice versa (Table 1, Cell 3: divergent leader internal attributions), attributional divergence occurs. Here, it is important to note that internal attributions occur when the attributor identifies a personal quality as the proximal cause of the negative achievement-related event. That is, the leader or follower makes a self-attribution. For example, if a follower makes a self-attribution to effort, she or he is likely to feel guilty and increase effort in the future as a way to make amends (Allred, 1995; Weiner, 2004).

Both dyadic partners need to feel that they have the ability to improve, they are connecting with each other, and they have some control for them to be motivated to engage in relationship work (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2000). However, because only one party is making a relational attribution, the relationship work will not be as successful in enhancing LMX quality as if both parties made the same attribution, resulting in stable or possible increases to LMX quality. Nevertheless, these divergent internal attributions are likely to result in leader or follower relationship work and some leader or follower self-work.

Proposition 3a.Divergent follower internal attributions (the combination of leader relational and follower internal attributions; Table 1, Cell 2) are likely to result in leader relationship work and some follower self-work, and LMX quality is likely to remain stable or increase.

Proposition 3b.Divergent leader internal attributions (the combination of leader internal and follower relational attributions; Table 1, Cell 3) are likely to result in follower relationship work and some leader self-work, and LMX quality is likely to remain stable or increase.

4.3 Divergent self attributions

If both the leader and the follower make internal attributions, they both attribute the cause to something about themselves (e.g., personal lack of effort or ability). As previously noted, the parties' attributions reflect divergence in this case because each party makes a self attribution and takes responsibility for the negative event (Table 1, Cell 4: divergent self attributions). Under these circumstances, no relationship work occurs, but each party engages in self-work because of guilt for their role in the adverse event. Indeed, Harvey et al. (2017) found that guilt was related to constructive workplace behaviors. Thus, the leader and follower may work to improve themselves by refining their skills to enhance future performance. Given that the leader and follower are engaged in self-work, LMX quality is unlikely to change unless the self-work facilitates better interpersonal exchanges.

Proposition 5.Divergent self attributions (the combination of leader internal and follower internal attributions; Table 1, Cell 4) are unlikely to result in relationship work; however, both leader and follower are likely to engage in self-work, and LMX quality is likely to remain stable or increase.

4.4 Divergent external-person attributions

When the follower makes a relational attribution and the leader attributes the unexpected negative event to the follower (Table 2, Cell 4: divergent leader external-person attributions), the follower is likely to engage in relationship work, whereas the leader may respond to his or her attribution by initiating conflict. Following the logic above, the follower is likely to experience guilt and engage in relationship work behaviors to address the task or personal elements of the relationship that she or he perceives as being related to the negative event. Conversely, the leader is attributing the negative event to the follower and hence is likely to experience frustration and/or anger. Weiner (1986) considered anger (like guilt) to be related to the controllability causal dimension. He viewed anger as an other-generated emotion that occurs because of attributions of lack of effort from the other party. Hareli and Rafaeli (2008) described how feelings of anger are commonly mimicked or transferred, particularly when the angry person is in a position of higher power (i.e., the leader). Therefore, as a result of the leader's anger and the divergent attributions, leader-initiated conflict is likely.

In addition, LMX quality is likely to decrease (Martinko, Moss, et al., 2007). Previous research suggested that divergent attributions may lead to deteriorating relationships (Martinko, Moss, et al., 2007). For example, if the follower feels unfairly blamed for a problem that is perceived as arising from issues in the relationship, he or she is likely to perceive a decrease in relationship quality. Without the benefit of the relational attribution construct, Martinko and Gardner (1987) nevertheless considered why these types of divergent attributions can be so counterproductive. They noted that “if the leader attributes failure to a lack of effort and responds by punishing the subordinate, the member probably will view the leader's response as inappropriate and conflict could occur” (p. 242). Note that in the scenario they described, we view the punishment administered by the leader as a form of leader-initiated conflict, because the leader takes action that the follower is likely to view as unjust, given his or her relational attribution. The follower, in turn, is likely to experience resentment, thereby escalating the conflict and causing LMX quality to suffer (Martinko, Sikora, & Harvey, 2012). This is consistent with affective events theory, which suggests that if a leader expresses anger to a follower, their relationship will be harmed (Cropanzano, Dasborough, & Weiss, 2017).

In a similar manner, the leader could attribute the cause of the negative event to the relationship, whereas the follower makes an external-person attribution by blaming the leader for the negative event (Table 2, Cell 2: divergent follower external-person attributions). This scenario is likely to lead to leader relationship work and follower-initiated conflict, even if the latter is passive aggressive due to the power differential between the leader and follower. However, it may become particularly problematic if the leader becomes angry for being held responsible for the event (when he or she attributes the negative event to the relationship) and because of the divergence in attributions. Likewise, the follower may feel frustrated and angry that their counterpart thought something was wrong with the relationship, which is likely to result in an escalation of conflict.

Proposition 5a.Divergent leader external-person attributions (the combination of leader external-person and follower relational attributions; Table 2, Cell 4) are likely to result in follower relationship work and leader-initiated conflict, and LMX quality is likely to decrease.

Proposition 5b.Divergent follower external-person attributions (the combination of leader relational and follower external-person attributions; Table 2, Cell 2) are likely to result in leader relationship work and follower-initiated conflict, and LMX quality is likely to decrease.

If both the leader and follower make an external-person attribution for poor performance (Table 2 Cell 5: divergent external-person attributions), they attribute the cause to their dyadic partner rather than to themselves. That is, they blame the other party for the negative outcome. In this scenario, the leader and the follower are likely to be angry with each other, and there is likely to be mutually-initiated conflict. Here, stronger workplace outcomes are possible, such as aggression or deliberate mistreatment, particularly if the follower views the leader as an abusive supervisor (Harvey, Summers, & Martinko, 2010). Moreover, this has the potential to be most detrimental to LMX quality because each party holds the other accountable for the negative and unexpected event.

Proposition 5c.Divergent external-person attributions (the combination of leader external-person and follower external-person attributions; Table 2, Cell 5) are likely to result in mutually-initiated conflict, and LMX quality is likely to decrease.

4.5 Divergent external-situational attributions

When one party makes a relational attribution while the other makes an external attribution to the situation (i.e., external-situational attribution; Table 2, Cell 7: divergent leader external-situational attributions, or Table 2, Cell 3: divergent follower external-situational attributions), the party making the relational attribution for the adverse event is likely to feel guilty and engage in task- or person-focused relationship work. Given that the other party attributed the negative event to the situation and not the other person, he or she is more likely to reciprocate the relationship work, signaling that he or she values the other party's effort and the relationship. Therefore, the increased effort devoted to the relationship is likely to cause LMX quality to remain stable or increase.

Proposition 6a.Divergent follower external-situational attributions (the combination of leader relational attributions and divergent follower-situation attributions; Table 2, Cell 3) are likely to result in leader relationship work, and LMX quality is likely to remain stable or increase.

Proposition 6b.Divergent leader external-situational attributions (the combination of leader external-situational and follower relational attributions; Table 2, Cell 7) are likely to result in follower relationship work, and LMX quality is likely to remain stable or increase.

4.6 Divergent external-person/situational attributions

When one party makes an external-situational attribution while the other makes an external-person attribution to the dyadic partner (i.e., divergent external-person/situational attributions; Table 2, Cell 6 and 8), conflict is likely and LMX quality is expected to decrease. Given that either the leader or the follower feels that the other party is responsible for the negative and unexpected event, they are likely to be angry and hold the partner accountable. When the leader (follower) makes an external-person attribution while the follower (leader) makes an external-situational attribution, leader (follower)-initiated conflict is likely to ensure. Additionally, given that there is divergence in attributions and one party is angry, LMX quality is likely to decrease.

Proposition 7a.Divergent external-person or situational attributions (the combination of leader external-person and follower external-situational attributions; Table 2, Cell 6) are likely to result in leader-initiated conflict, and LMX quality is likely to decrease.

Proposition 7b.Divergent external-person/situational attributions (the combination of leader external situational and follower external person; Table 2, Cell 8) are likely to result in follower-initiated conflict, and LMX quality is likely to decrease.

4.7 Convergent external-situational attributions

When the leader and follower both make attributions to the external situation (Table 2, Cell 9: convergent external-situational attributions), no relationship work, self-work, or conflict is expected, and LMX quality remains stable. This proposition follows from the fact that neither party views the relationship as the cause of the negative and unexpected event, so it is unlikely that either the leader or the follower will see a need for relationship work. Moreover, both parties attribute the cause to an external-situational factor (e.g., luck and task difficulty), so it is unlikely to elicit feelings of guilt or anger, which would prompt self-work or conflict.

Proposition 13.Convergent external-situational attributions (the combination of leader external-situational and follower external-situational attributions; Table 2, Cell 9) are unlikely to result in relationship work, self-work, or conflict, and LMX quality is likely to remain stable.

5 THE INTERACTION OF ATTRIBUTION COMBINATIONS AND LMX QUALITY

The final part of our model suggests that LMX quality will moderate the relationship between attribution combinations and outcomes. Note that we propose moderated relationships between attribution combinations and the interpersonal dependent variables (i.e., relationship work and conflict), but not self-work. This is because self-work is an intrapersonal effort to improve one's task-related skills or personal abilities, which is less likely to be affected by relationship quality.

According to Eberly et al. (2011), when one party in the relationship makes a relational attribution, she or he cannot be sure that her or his dyadic partner will make the same attribution. Therefore, the partner may choose to voice the relationship concerns to the other party to ensure that both are in agreement. This task- or person-focused voice activity is the first step toward conflict management (Peirce, Pruitt, & Czaja, 1993). Dyadic partners with a high-quality LMX relationship are more likely to voice their relational concerns (Botero & Van Dyne, 2009; Mowbray, Wilkinson, & Tse, 2015) and therefore work toward resolving discrepancies in their attributions. This is likely to result in the dyad coming together to achieve relationship work when needed, and it is likely to reduce conflict between the leader and follower.

Proposition 9a.LMX quality positively moderates the relationship between leader–follower attribution combinations and relationship work such that the leader–follower attribution combinations are related to higher levels of relationship work in dyads with high-quality LMX as opposed to low-quality LMX relationships.

Proposition 9b.LMX quality negatively moderates the relationship between the leader–follower attribution combinations and conflict such that leader–follower attribution combinations are related to lower levels of conflict in dyads with high-quality LMX as opposed to low-quality LMX relationships.

6 ATTRIBUTION COMBINATIONS AND LEVELS OF RELATIONSHIP WORK

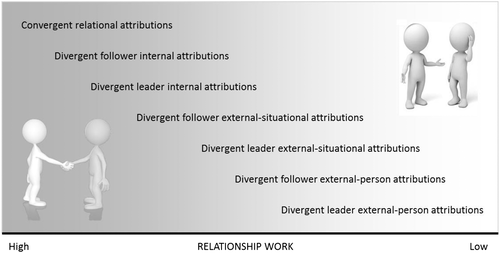

Throughout the preceding discussion of the various combinations of leader and follower attributions, a hierarchical relationship between particular attribution combinations and the amount of ensuing relationship work is implied. In this section, we make the implicit ranking of attribution combinations and the resultant levels of relationship work explicit, as illustrated in Figure 2. Note that the amount of relationship work associated with particular attribution combinations is depicted as varying from high to low levels.

Before we introduce the theoretical rationale for the relationships depicted in Figure 2, we first expand upon our model's assumptions by articulating the implicit assumptions that underlie the proposed hierarchy of attribution combinations and relationship work.

Assumption 1.Convergent relational attributions produce the highest levels of relationship work, because both parties attribute the negative achievement-related event to the relationship—a scenario that Eberly et al. (2011) posited would be most likely to yield relationship work.

Assumption 2.The power differential that exists between leaders and followers will make it more likely that when a leader makes a relational attribution but the follower does not, subsequent relationship work initiated by the leader will be reciprocated (Eberly et al., 2011; Emerson, 1962), than is the case when the follower makes a relational attribution but the leader does not.

Assumption 3.Attribution combinations that reflect a relational attribution and subsequent relationship work by one party and an internal attribution and self-work by the other party will be more likely to yield reciprocation of the relationship work than cases where a relational attribution is combined with an external attribution by the other party. This is because both parties are focused on engaging in work to directly (relationship work) or indirectly (self-work) improve the relationship (Eberly et al., 2011).

Assumption 4.Higher levels of relationship work will arise when a relational attribution by one party is combined with an external-situational attribution as opposed to an external-person attribution by the other party, because of the blame and potential for conflict that arises from external-person attributions (Martinko & Gardner, 1987; Weiner, 1985, 1986).

Together, these assumptions indicate that convergent relational attributions will yield the highest levels of relationship work, as noted above (Assumption ). Divergent follower internal attributions will yield the second highest levels of relationship work, because the leader makes a relational attribution and initiates relationship work and the follower makes an internal (self) attribution and initiates self-work (Assumption ). Under these conditions, the follower may be eager to reciprocate the relationship work of the leader (Eberly et al., 2011), because the relationship work and self-work are likely to be viewed as complementary and efficacious for preserving and/or enhancing LMX quality.

The next highest level of relationship work will occur when the follower makes a relational attribution and initiates relationship work, and the leader makes an internal (self) attribution and initiates self-work. Here, again, we view this combination as one that is conducive to reciprocation of relationship work on the part of the leader (Assumption ) but not as much so as in the prior scenario. This is because leaders are less likely to emulate the behavior of followers (Eberly et al., 2011) than vice versa (Assumption ).

Next, we posit that the divergent follower external-situational and divergent leader external-situational attribution combinations will yield intermediate levels of relationship work because one party is making a relational attribution and initiating relationship work and the other is making an external-situational attribution. That is, even though one party sees the situation as being responsible for the negative event, and hence sees no initial need for relationship work or self-work, he or she may nonetheless choose to reciprocate the relationship work of the other party once it is initiated. However, we see such reciprocation as being less likely than is the case for divergent internal attributions, where the party making the divergent attribution initiates self-work (Assumption ). Additionally, we again posit that divergent follower external-situational attributions as opposed to divergent leader external-situational attributions will be more likely to yield reciprocation of relationship work, given the power differential that exists between leaders and followers (Martinez, Kane, Ferris, & Brooks, 2012; Assumption ).

At the lowest levels of the hierarchy are divergent follower and leader external-person attributions, where one party makes a relational attribution but the other party attributes the negative and unexpected event to their dyadic partner. Because the party making the relational attribution is likely to initiate relationship work, we think there is a possibility that the other party will reciprocate. However, because the other party views the party making the relational attribution as being responsible for the event, she or he is less likely to reciprocate relationship work than is the case when external-situational attributions are made (Assumption ). And, once again, we expect relationship work initiated by the leader will be more likely to be reciprocated than relationship work initiated by the follower (Assumption ).

Finally, because both parties attribute the negative achievement-related event to external causes for divergent external-person (Cell 5), divergent external-person/situational (Cells 6 and 8), and convergent external-situational (Cell 9) attributions, no relationship work by either party is expected. Hence, these combinations are omitted from Figure 1, which focuses exclusively on attribution combinations for which some relationship work by one or more parties is posited.

Proposition 16.Convergent relational attributions will elicit the highest levels of relationship work, followed, in declining magnitude, by divergent follower internal attributions, divergent leader internal attributions, divergent follower external-situational attributions, divergent leader external-situational attributions, divergent follower external-person attributions, and divergent leader external-person attributions; no relationship work is expected for divergent external-person/situational attributions, and convergent external-situational attributions.

7 DISCUSSION

In the preceding sections, we discussed how convergent or divergent internal, external-person, external-situational, and relational attribution combinations affect leader and follower relationship work, self-work, and conflict. We now turn our attention to considering the implications of this work for research on relational attribution theory, social comparisons, time, and impression management.

7.1 Relational attribution theory implications

A central point of this paper was further integration of attribution theories with recent research on relational attributions and LMX theories. In integrating these literatures, we propose that as the intensity of self-serving or actor-observer attributional bias(es) experienced by leaders and/or followers increases, they become less likely to make relational attributions. Although our discussion of attributional biases was bounded by our discussion of the self-serving bias and the actor-observer bias, we acknowledge that there are numerous other attribution biases that could impact the propensity for leaders and/or followers to make relational attributions, and those warrant further theoretical integration in future research.

In addition, our discussion of emotions related to attributions focuses on the impact of guilt and anger. This led to two interesting insights. First, combinations of relational and internal attributions for the negative event are likely to elicit guilt, which is likely to prompt leader and/or follower self-work or relationship work. Conversely, combinations of relational and external-person/situational attributions are likely to elicit guilt or anger, which likely results in leader and/or follower relationship work or conflict. However, Weiner's (1986) research highlighted a range of emotions from positive (e.g., pleased, satisfied, proud, and confident) to negative (e.g., sad, pity, bitter, and disgust) that have yet to be integrated into relational attribution research. Therefore, future relational attribution research should explicitly examine how other emotions are connected to behavior.

Finally, we acknowledge that relational attribution research is still in its infancy given that the publication of the seminal theoretical piece by Eberly and colleagues occurred just 8 years ago (2011). Accordingly, there are relatively few empirical studies that have examined relational attributions. This is reflective of what Reichers and Schneider (1990) describe as the first stage of the model for the evolution of constructs. In this stage, they argue that it is important to introduce and theoretically elaborate a topic. Therefore, there are additional needs for theorizing on relational attributions, dyadic-level attribution combinations, and their potential impact on other social exchange quality variables (e.g., affective commitment and trust) and outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behaviors).

7.2 Social comparison implications

When considering LMX and relational attributions, we must consider that the leader–member relationship is situated in an environment where the leader has relationships with all of her or his employees that vary in quality. Because employees all have distinct relationships with their leader, social comparisons regarding their relationship with the leader are likely to occur. Wood (1986) defined social comparison as “the process of thinking about information about one or more other people in relation to the self” (pp. 520–521). Therefore, employees are likely to compare their relationship with other employees and will judge the quality of LMX on the basis of this comparison. As such, the social comparison context is a vital factor to consider. Social comparison processes impact relational attributions and the motivation of leaders and followers to engage in relationship work. Social comparison theory states that people evaluate themselves by comparing their opinions and behaviors with those of other people, particularly those who are similar, as would be the case among coworkers (Festinger, 1954).

In a leader–follower relationship, followers compare their relationship with the leader to their coworkers' relationships with the leader. This between-person appraisal is a way in which followers seek consensus information (Kelley, 1973). Upon doing so, if an employee does not perceive that the leader is being consistent across relationships, the quality of the social exchange will be hindered (Colquitt et al., 2013; Masterson, Lewis, Goldman, & Taylor, 2000; Rupp, Shao, Jones, & Liao, 2014). This is particularly salient for leaders because employees may view the relationship as unfair when compared with another employee's relationship with the leader. If a follower does not perceive fairness in the relationship due to the leader's behavior, the follower is likely to blame the leader for relationship problems, rather than making a relational attribution, and is less likely to be motivated to engage in relationship work. In other words, depending on the participant's social comparison process, relationship work may be less likely to occur.

7.3 Time implications

As we have discussed, there are characteristics of the situation or context beyond interdependence that impact relational attributions. Specifically, for the leader–member relationship, future research should consider the history of the relationship between the leader and follower when analyzing the likelihood of relational attributions and relationship work. Of particular interest would be an examination of the type, frequency, and strength of negative and unexpected events in the relationship's history. For example, distinctiveness (i.e., comparing one's behavior across situations) and consistency information (i.e., comparing whether one's behavior changes across time) in response to negative or unexpected events could be used to explore whether relational attributions are more or less likely in long-tenured dyadic relationships. Moreover, consensus information (i.e., considering whether the other party's behavior is consistent with others) could be examined to determine whether in-group or out-group followers are less likely to make relational attributions.

According to Burger (1991), attributions change over time. Specifically, he or she found that the fundamental attribution error (a common attributional bias) diminished significantly over time to the point that research participants stopped utilizing personal information in making attributions about others when there was a time lag in making the attribution (Burger, 1991; Burger & Pavelich, 1994). When applying these findings to relational attributions and LMX, we can see how vital the change over time is to consider. In the beginning stages of the relationship, there may be a tendency for divergent external attributions due to attributional biases. However, as the relationship improves over time, these biases are likely to diminish, therefore changing how the participants view the negative achievement-related event. For example, if conflict occurs within the leader–follower relationship soon after the participants start working together, they may blame each other, therefore causing more conflict. However, based on Burger's (1991) research, after a period of time, the participants are likely to look back on that initial conflict and make less biased attributions. Furthermore, being able to reflect on these past conflicts may further enhance LMX quality, because this will enable them to learn from the experience. Therefore, as noted by previous researchers (Chong et al., 2015; Eberly et al., 2017), time continues to be an important aspect to consider in future research when examining the relational attribution–LMX relationship.

7.4 Impression management implications

Relationship work occurs when participants in a relationship want to improve or repair the relationship. In some cases, this may involve impression management. Previous research has suggested that impression management in the form of shaping others' attributions can influence others' behaviors (Bolino, Long, & Turnley, 2016; Gardner & Martinko, 1988; Jones & Pittman, 1982). In terms of relational attributions and LMX, this may mean that one party apologizes, uses ingratiation, or attempts to justify the negative event. Specifically, in the beginning of a leader–member relationship, this may be more likely than later, when LMX is of higher quality. The impression management literature may give some insights as to how impression management may change over time regarding relationship work; such changes should be considered in future research. For example, are subordinates more likely to use self-promotion as an impression management tactic to build a reputation for competence and make it less likely that they will be held responsible for negative events during early versus late stages in the relationship? We suspect motives for self-promotion decline as the relationship matures and followers (and leaders) grow more comfortable revealing their authentic selves (Gardner, Avolio, Luthans, May, & Walumbwa, 2005). Further, followers may be more comfortable exhibiting task- and person-focused voice behavior during the mature stages in the LMX relationship, particularly if the relationship is of high quality. Hence, future research that explores the extent to which the dyadic partners engage in strategic impression management as opposed to more authentic self-presentations is warranted.

7.5 Attribution training implications

For relationship work to occur, leaders and/or followers may need attributional training. Attribution theorists (Green & Mitchell, 1979; Martinko & Gardner, 1982, 1987) assert that attributional training is an effective tool for eliciting more constructive attributions from underperforming followers, as well as more objective attributions from leaders. In the social psychology literature, the situated attribution training technique has been used to help people overcome stereotyping by steering them away from dispositional attributions to more situational attributions for stereotype consistent behaviors (Stewart, Latu, Kawakami, & Myers, 2010). Support has been found for the efficacy of such training in the workplace. Researchers have used cognitive–behavioral training to elicit improvements in attributional style, job satisfaction, self-esteem, well-being, and productivity (Proudfoot, Corr, Guest, & Dunn, 2009). This research has also demonstrated that attribution training reduces employee turnover (Proudfoot et al., 2009). Therefore, attributional training may have utility in directing followers and leaders away from pessimistic attributions for poor performance toward more optimistic and realistic attributions pertaining to shortcomings in the relationship, which can be addressed through relationship work. This can occur by directing leaders and followers to consider whether there was high distinctiveness (e.g., similar or different personal behavior/outcomes in other situations), high consistency (e.g., similar or different personal behavior/outcomes across time), and low consensus (e.g., similar or different behavior from the dyadic partner) information following the poor performance event. Therefore, future research should consider attributional training and its effect on subsequent relationship work.

8 CONCLUSION

Throughout this paper, we have integrated attribution theories, relational attributions, and LMX theory to more fully elucidate previously developed theoretical models. We have explained how leader–follower relational and internal attribution combinations are likely to increase the quality of leader–member relationships, whereas leader–follower relational and external-person/situational attribution combinations are more likely to decrease the quality of leader–member relationships. We further discussed how convergent or divergent attributions impact emotions (i.e., guilt and anger) and subsequent relationship work, self-work, and conflict. In doing so, we have integrated and extended theory by attributional scholars including Kelley (1967, 1973), Weiner (1985), Martinko and Gardner (1987), and Eberly et al. (2011), and we have connected our work to research on social comparisons, time, impression management, and attributional training.

As management scholars continue to advance our understanding of the important leader–follower relationship, this research has the potential to impact practitioners as well. First, we provide insights into why leader and follower attributions following important, novel, and/or unexpected negative events may impact both positive (i.e., self-work and relationship work) and negative (i.e., conflict) workplace behaviors, which may be helpful for attributional training (as noted above). Additionally, we suggest a rationale for why leaders and followers engage in varying levels of relationship work. This has the potential to explain how leader–follower relationships evolve over time and to provide guidance for interventions to ensure relationships progress favorably and productively. Indeed, our hope is that the model and propositions presented herein spur empirical examinations of the relationships between attributional biases, convergent and divergent attribution combinations, and intrapersonal and interpersonal outcomes to further elucidate its theoretical and practical implications.

Biographies

William L. Gardner is the Jerry S. Rawls Chair in Leadership and Director of the Institute for Leadership Research at the Texas Tech University. His research interests include leadership, attribution theory, impression management, teams, and influence processes within organizations.

Elizabeth P. Karam is an Assistant Professor of Management in the Rawls College of Business at the Texas Tech University. Her research interests include leadership, teams, organizational justice, organizational culture, attribution theory, and human resource management.

Lori L. Tribble is a doctoral candidate in the Rawls College of Business at the Texas Tech University. Her research interests include strategic management, entrepreneurship, leadership, attribution theory, and family business.

Claudia C. Cogliser is a Professor of Management in the Rawls College of Business at the Texas Tech University. Her research interests include leadership, workforce diversity, virtual teams, attribution theory, and construct measurement.