Metformin use and the risks of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in patients with type 2 diabetes

Abstract

Herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia cause substantial pain in patients. Persons with type 2 diabetes (T2D) are prone to zoster infection and postherpetic neuralgia due to compromised immunity. We conducted this study to evaluate the risks of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia between metformin users and nonusers. Propensity score matching was utilized to select 47 472 pairs of metformin users and nonusers from Taiwan's National Health Insurance Research Database between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2017. The Cox proportional hazards models were used for comparing the risks of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia between metformin users and nonusers in patients with T2D. Compared with no-use of metformin, the adjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence interval) for metformin use in herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia were 0.70 (0.66, 0.75) and 0.510 (0.39, 0.68), respectively. A higher cumulative dose of metformin had further lower risks of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia than metformin no-use. This nationwide cohort study demonstrated that metformin use was associated with a significantly lower risk of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia than metformin no-use. Moreover, a higher cumulative dose of metformin was associated with further lower risks of these outcomes.

Abbreviations

-

- AMPK

-

- AMP-activated protein kinase

-

- CAD

-

- coronary artery disease

-

- CCI

-

- Charlson Comorbidity Index

-

- COPD

-

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

-

- DCSI

-

- Diabetes Complication Severity Index

-

- OAD

-

- oral antidiabetic drugs

-

- SLE

-

- systemic lupus erythematosus

-

- T2D

-

- type 2 diabetes

-

- TZD

-

- thiazolidinedione

-

- VZV

-

- varicella-zoster virus

1 INTRODUCTION

Once a patient has had chickenpox or received the varicella vaccine, the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) can become latent in the sensory ganglia. A decline in cell-mediated immunity can cause the virus to reactivate and spread along the sensory nerve to the skin with the development of herpes zoster.1, 2 In about 10%–50% of patients with zoster, pain may persist for 90 days or more due to postherpetic neuralgia (PHN).1 Although attenuated varicella and zoster vaccines have been available since 1995, the incidence of varicella and zoster has increased worldwide.2 The global numbers of cases with varicella and zoster in 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2019 were 71.25, 73.79, 79.52, and 83.96 million, respectively.3

Older adults (with a gradual decline in immunity due to aging) and patients with cancer or autoimmune diseases on immunosuppressive drugs are high-risk groups for herpes zoster.2, 4 It is not uncommon that persons with type 2 diabetes (T2D) show compromised immune function due to chronic hyperglycemia. Studies have reported that persons with T2D are more likely to develop zoster and PHN.4 Although medications for treating zoster are available, many patients with PHN show low treatment satisfaction.5 PHN is a complicated neuropathic pain that can be severe and long-lasting and significantly impact the social, physical, and psychological aspects of quality of life.5

Metformin is a synthetic derivative of guanidine, isolated from the extract of Galega officinalis, with a prominent antidiabetic effect noted since the 1920s.6 The UK Prospective Diabetes Study (1998) demonstrated that metformin could significantly reduce cardiovascular events in patients with T2D.7 Metformin has been used worldwide since 1998, and it is by far the first-line antidiabetic drug for the management of T2D.6 Metformin was also used for treating malaria and influenza in the 1940s.6 Reports show beneficial effects of treatment for tuberculosis and sepsis.8 Studies show that metformin reduces the severity and mortality of COVID-19.9 Preclinical studies have shown that metformin can decrease the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and improve T-cell immunity through the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK).8-10 Therefore, we hypothesized that metformin could diminish the risk of herpes zoster and PHN. We, herein, designed this study to compare the incidence of zoster and PHN between metformin users and nonusers in patients with T2D.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study population

The Taiwan government implemented the National Health Insurance (NHI) program in 1995. The government is the single buyer of this national insurance system. Most of the premiums are paid by the employers and the government, and the public pays a small amount. By 2000, the insurance program covered over 95% of the 23 million people.11 The information about the insurer's residential area, age, sex, premium, diagnosis, prescriptions, and medical procedures is recorded in the NHI Research Database (NHIRD). Diagnosis is established according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM). The NHIRD data are linked to the National Death Registry to confirm death information. This study identified patients from the NHIRD and received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of China Medical University and Hospital [CMUH109-REC2-031(CR-2)]. The identifiable information of health providers and patients was encrypted before release to protect individual privacy. Informed consent was waived by the Research Ethics Committee.

2.2 Study design

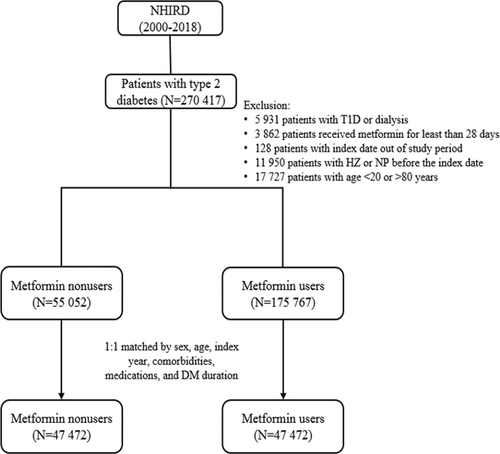

We recognized newly diagnosed T2D patients between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2017, and followed them till December 31, 2018. Diagnosis of T2D was based on ICD codes (ICD-9 code: 250, except 250.1x; ICD-10: E11. Additional File 1: Table S1) for at least 3 outpatient visits within 1 year or one hospitalization record. The algorithm of using ICD codes to define T2D was validated by a previous Taiwan study with an accuracy of 74.6%.12 Patients were excluded (Figure 1) under the following conditions: (1) age below 20 or above 80 years; (2) missing sex or age data; (3) diagnosis of type 1 diabetes, hepatic failure, or under dialysis; (4) diagnosis of herpes zoster or PHN before the index date. (5) diagnosis of T2D before January 1, 2000 (to exclude prevalent T2D cases).

2.3 Procedures

Patients who received metformin treatment were study cases, and those who never used metformin during the follow-up period served as control cases. The first date of metformin use was defined as the index date. The index date of metformin nonusers was assigned as the same period from the diagnosis of T2D to the index date of their corresponding metformin users. Some critical variables calculated and matched between metformin users and nonusers were as follows: age, sex, obesity, smoking, comorbidities of alcohol-related disorders, hypertension, dyslipidemia, coronary artery disease, stroke, heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), liver cirrhosis, cancers, psychosis, depression, and dementia, diagnosed within 1 year before the index date; medications, including sulfonylureas, thiazolidinedione, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, items and number of oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs), glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA), insulin, statins, corticosteroids, and aspirin, during the follow-up period. We also assessed the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), Diabetes Complication Severity Index (DCSI) scores,13, 14 duration of diabetes, and the number of OADs to evaluate T2D severity. We assessed the HbA1c check-up >2 times per year to evaluate the frequency of hospital visits due to diabetes between the study and control groups.

2.4 Main outcomes

We calculated and compared the incidence rate of herpes zoster and PHN in the time-scale of 1000 person-years between study and control groups. The cumulative incidences of herpes zoster and PHN were compared between metformin users and nonusers during the follow-up time. In calculating the incidence of PHN, we used patients with herpes zoster as the denominator, and the first date of herpes zoster diagnosis as the index date to compare the incidence of PHN between metformin users and nonusers.

2.5 Statistical analysis

Propensity-score matching was adopted to optimize compatibility of the relevant variables between metformin users and nonusers.15 The propensity score was estimated using nonparsimonious multivariable logistic regression for each patient, with metformin use as the dependent variable and 40 relevant variables as independent variables (Table 1). The nearest-neighbor algorithm was used to construct matched pairs, assuming the standardized mean difference (SMD) <0.1 to be a negligible difference between study and comparison cohorts.

| Variables | Metformin nonusers (N = 47 472) | Metformin users (N = 47 472) | SMD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | 0.014 | ||||

| Female | 23 020 | 48.5 | 23 357 | 49.20 | |

| Male | 24 452 | 51.5 | 24 115 | 50.80 | |

| Age | |||||

| 20–40 | 3887 | 8.2 | 3755 | 7.91 | 0.010 |

| 41–60 | 20 709 | 43.6 | 20 411 | 43.00 | 0.013 |

| 61–80 | 22 876 | 48.2 | 23 306 | 49.09 | 0.018 |

| mean (SD)a | 59.19 | (12.5) | 59.44 | (12.3) | 0.020 |

| Obesity | 1385 | 2.9 | 1381 | 2.91 | 0.001 |

| Smoking | 1296 | 2.7 | 1298 | 2.73 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Alcohol-related disorders | 2221 | 4.7 | 2206 | 4.65 | 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 29 772 | 62.7 | 30 376 | 63.99 | 0.026 |

| Dyslipidemia | 28 972 | 61.0 | 29 539 | 62.22 | 0.025 |

| CAD | 15 503 | 32.7 | 15 652 | 32.97 | 0.007 |

| Stroke | 8950 | 18.9 | 9020 | 19.00 | 0.004 |

| Heart failure | 4665 | 9.8 | 4709 | 9.92 | 0.003 |

| PAD | 2024 | 4.3 | 1998 | 4.21 | 0.003 |

| CKD | 7911 | 16.7 | 7856 | 16.55 | 0.003 |

| COPD | 14 656 | 30.9 | 14 931 | 31.45 | 0.013 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 176 | 0.4 | 183 | 0.39 | 0.002 |

| SLE | 41 | 0.1 | 44 | 0.09 | 0.002 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 1921 | 4.0 | 1906 | 4.02 | 0.002 |

| Cancer | 5001 | 10.5 | 5149 | 10.85 | 0.010 |

| Psychosis | 4915 | 10.4 | 4834 | 10.18 | 0.006 |

| Depression | 17 436 | 36.7 | 17 514 | 36.89 | 0.003 |

| Dementia | 243 | 0.5 | 213 | 0.45 | 0.009 |

| CCI | |||||

| 1 | 36 931 | 77.8 | 36 854 | 77.63 | 0.004 |

| 2–3 | 7443 | 15.7 | 7651 | 16.12 | 0.012 |

| >3 | 3098 | 6.5 | 2967 | 6.25 | 0.011 |

| DCSI | |||||

| 0 | 15 437 | 32.5 | 15 210 | 32.04 | 0.010 |

| 1 | 8977 | 18.9 | 9041 | 19.04 | 0.003 |

| ≥2 | 23 058 | 48.6 | 23 221 | 48.92 | 0.007 |

| Medications | |||||

| Sulfonylureas | 7798 | 16.4 | 18 361 | 38.68 | 0.514 |

| Thiazolidinedione | 805 | 1.7 | 901 | 1.90 | 0.015 |

| Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors | 978 | 2.1 | 1427 | 3.01 | 0.060 |

| Alpha-glucosidase inhibitor | 1769 | 3.7 | 1727 | 3.64 | 0.005 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 33 | 0.1 | 39 | 0.08 | 0.005 |

| OAD numbers | |||||

| 0–1 | 45 779 | 96.4 | 45 862 | 96.61 | 0.010 |

| 2–3 | 1657 | 3.5 | 1579 | 3.33 | 0.009 |

| >3 | 36 | 0.1 | 31 | 0.07 | 0.004 |

| Insulin | 19 878 | 41.9 | 20 063 | 42.26 | 0.008 |

| Corticosteroids | 523 | 1.1 | 520 | 1.10 | 0.001 |

| Immunosuppressants | 362 | 0.8 | 362 | 0.76 | 0.000 |

| Statins | 17 584 | 37.0 | 18 026 | 37.97 | 0.019 |

| Aspirin | 20 248 | 42.7 | 20 555 | 43.30 | 0.013 |

| Duration of diabetes | |||||

| mean (SD) | 3.36 | (3.46) | 3.14 | (3.67) | 0.060 |

| HbA1c check-up >2 per year | 29 781 | 62.7 | 30 209 | 63.64 | 0.019 |

- Note: Data shown as n (%) or mean ± SD. SMD < 0.1 indicates no significant difference between metformin users and nonusers.

- Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CCI; Charlson Comorbidity Index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DCSI, Diabetes Complications Severity Index; OAD, oral antidiabetic drug; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; SD, standard deviation; SGLT2, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SMD, standardized mean difference.

- a The Student t-test.

The study used crude and multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional hazards models to evaluate the outcomes between metformin users and nonusers. The results were presented as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for metformin users compared with nonusers. To assess the observed risks, we censored patients on the date of respective outcomes, death, or at the end of the follow-up on December 31, 2018, whichever came first. The Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank tests compared the cumulative incidences of herpes zoster and PHN between metformin users and nonusers during the follow-up period. We also investigated the cumulative dose (<350, 350–1320, >1320 mg) of metformin and the risks of herpes zoster and PHN compared with metformin no-use. The cumulative dose of metformin use was calculated by summing up the metformin dosage from the first to the last prescription during the observation period. To eliminate immortal time bias, we further performed time-dependent analysis. For metformin nonusers, we assigned the date of T2D diagnosis as the index date. For metformin users, from the date of T2D diagnosis to the first metformin prescription date was defined as the metformin nonuse period; and then the first metformin prescription date was defined as the index date of metformin users.

SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute) was used for statistical analysis, and a two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered significant.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Participants

From January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2017, we identified 270 417 patients with newly diagnosed T2D; 175 767 were metformin users, and 55 052 were nonusers (Figure 1). After excluding ineligible cases, 1:1 propensity score matching was used to construct 47 472 pairs of metformin users and nonusers. In the matched cohorts (Table 1), 48.85% of patients were female; the mean (SD) age was 59.32 (12.4) years. The mean follow-up time for metformin users and nonusers was 4.85 (3.97) and 4.1 (3.79) years, respectively.

3.2 Main outcomes

In the matched cohorts, 1864 (3.93%) metformin users and 2153 (4.54%) nonusers developed herpes zoster during the follow-up period (incidence rate: 8.1 vs. 11.1 per 1000 person-years). In the multivariable model, metformin users showed a significantly lower risk of herpes zoster (aHR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.66–0.75). Patients aged 41–60 years and 61–80 years with COPD, RA, SLE, cancer, depression, on insulin, and immunosuppressants showed a significantly higher risk of herpes zoster, but those with psychosis had a significantly lower risk of zoster (Table 2). Because sulfonylureas use was not matched well between the metformin users and nonusers (SMD = 0.514), we performed a subgroup analysis (Table S2) to observe if the effects of metformin use would be influenced by sulfonylureas use. The subgroup analysis showed that metformin use was associated with a significantly lower risk of herpes zoster in both patients with (aHR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.51–0.66) and without sulfonylureas use (aHR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.69–0.81). The time-dependent analysis, which adjusted impacts of the time-varying exposure of metformin, and other medications on the metformin-associated risk of herpes zoster, showed that metformin users had a significantly lower risk of herpes zoster (aHR = 0.57, 95% CI = 0.52–0.62) compared with nonusers (Table S3).

| Variables | Herpes zoster | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | PY | IR | cHR | (95% CI) | p value | aHRa | (95% CI) | p value | |

| Metformin nonusers | 2153 | 194 643 | 11.1 | 1.00 | (reference) | – | 1.00 | (reference) | – |

| Metformin users | 1864 | 230 082 | 8.1 | 0.73 | (0.69, 0.78) | <0.001 | 0.70 | (0.66, 0.75) | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| female | 2249 | 222 873 | 10.1 | 1.00 | (reference) | – | 1.00 | (reference) | – |

| male | 1768 | 201 852 | 8.8 | 0.87 | (0.82, 0.92) | <0.001 | 0.94 | (0.88, 1.01) | 0.080 |

| Age | |||||||||

| 20–40 | 125 | 38 108 | 3.3 | 1.00 | (reference) | – | 1.00 | (reference) | – |

| 41–60 | 1489 | 188 163 | 7.9 | 2.41 | (2.01, 2.89) | <0.001 | 2.29 | (1.90, 2.76) | <0.001 |

| 61–80 | 2403 | 198 454 | 12.1 | 3.69 | (3.08, 4.42) | <0.001 | 3.36 | (2.79, 4.05) | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 80 | 11 655 | 6.9 | 0.72 | (0.58, 0.90) | 0.004 | 0.89 | (0.71, 1.11) | 0.295 |

| Smoking | 67 | 7455 | 9.0 | 0.95 | (0.75, 1.21) | 0.674 | 1.07 | (0.84, 1.36) | 0.596 |

| Comorbidities | |||||||||

| Alcohol disorders | 120 | 15 736 | 7.6 | 0.80 | (0.67, 0.96) | 0.016 | 0.97 | (0.80, 1.18) | 0.756 |

| COPD | 1513 | 129 510 | 11.7 | 1.38 | (1.29, 1.47) | <0.001 | 1.18 | (1.11, 1.27) | <0.001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 35 | 1753 | 20.0 | 2.12 | (1.52, 2.96) | <0.001 | 1.58 | (1.11, 2.25) | 0.011 |

| SLE | 9 | 438 | 20.5 | 2.18 | (1.14, 4.19) | 0.019 | 2.07 | (1.07, 4.01) | 0.031 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 134 | 13 352 | 10.0 | 1.06 | (0.90, 1.26) | 0.477 | 1.07 | (0.89, 1.29) | 0.446 |

| Cancer | 611 | 44 440 | 13.7 | 1.53 | (1.41, 1.67) | <0.001 | 1.43 | (1.30, 1.57) | <0.001 |

| Psychosis | 332 | 39 175 | 8.5 | 0.89 | (0.79, 0.99) | 0.034 | 0.80 | (0.71, 0.90) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 1685 | 156 515 | 10.8 | 1.24 | (1.16, 1.32) | <0.001 | 1.13 | (1.05, 1.21) | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 14 | 1326 | 10.6 | 1.11 | (0.66, 1.88) | 0.687 | 1.16 | (0.68, 1.99) | 0.590 |

| DCSI | |||||||||

| 0 | 1211 | 146 725 | 8.3 | 1.00 | (reference) | – | 1.00 | (reference) | – |

| 1 | 795 | 84 953 | 9.4 | 1.13 | (1.04, 1.24) | 0.006 | 0.96 | (0.88, 1.06) | 0.451 |

| ≥2 | 2011 | 193 047 | 10.4 | 1.26 | (1.18, 1.36) | <0.001 | 0.96 | (0.87, 1.06) | 0.388 |

| Medications | |||||||||

| Sulfonylureas | 1282 | 139 640 | 9.2 | 0.96 | (0.90, 1.02) | 0.200 | 1.04 | (0.97, 1.12) | 0.240 |

| OAD number | |||||||||

| 0–1 | 3897 | 413 635 | 9.4 | 1.00 | (reference) | – | 1.00 | (reference) | – |

| 2–3 | 116 | 10 926 | 10.6 | 1.13 | (0.94, 1.35) | 0.208 | 1.07 | (0.89, 1.29) | 0.474 |

| >3 | 4 | 164 | 24.4 | 2.59 | (0.97, 6.91) | 0.057 | 2.07 | (0.78, 5.54) | 0.146 |

| Insulin | 1812 | 167 861 | 10.8 | 1.26 | (1.18, 1.34) | <0.001 | 1.15 | (1.07, 1.23) | <0.001 |

| Corticosteroids | 43 | 4201 | 10.2 | 1.08 | (0.80, 1.46) | 0.604 | 1.05 | (0.78, 1.42) | 0.732 |

| Immunosuppressants | 48 | 2199 | 21.8 | 2.32 | (1.75, 3.09) | <0.001 | 2.13 | (1.57, 2.89) | <0.001 |

- Abbreviations: aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; cHR, crude hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DCSI, Diabetes Complications Severity Index; IR, incidence rate, per 1,000 person-years; OAD, oral antidiabetic drug; PY, person-years; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

- a Multivariable analysis, including sex, age, comorbidities, CCI, DCSI, corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, statins, aspirin, insulin, item and number of oral antidiabetic drugs, duration of diabetes, and HbA1c check-up per year.

Among those who had herpes zoster infection, 80 metformin users and 257 nonusers got PHN during the follow-up period (incidence rate: 8.9 vs. 42.53 per 1000 person-years). The multivariable analysis showed that metformin users had a significantly lower risk of PHN (aHR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.39–0.68) in T2D patients with herpes zoster infection. Patients with SLE, psychosis, depression, and receiving insulin showed a significantly higher risk of PHN (Table 3).

| Variables | Postherpetic neuralgia | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | PY | IR | cHR | (95% CI) | p value | aHRa | (95% CI) | p value | |

| Metformin nonusers | 257 | 6043 | 42.53 | 1 | (reference) | – | 1 | (reference) | – |

| Metformin users | 80 | 8989 | 8.90 | 0.48 | (0.36, 0.63) | <0.001 | 0.51 | (0.39, 0.68) | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| female | 211 | 8541 | 24.70 | 1.00 | (reference) | – | 1.00 | (reference) | – |

| male | 126 | 6491 | 19.41 | 0.74 | (0.56, 0.98)* | 0.037 | 0.89 | (0.66, 1.19) | 0.423 |

| Age | |||||||||

| 20–40 | 5 | 503 | 9.94 | 1.00 | (reference) | – | 1.00 | (reference) | – |

| 41–60 | 127 | 5709 | 22.24 | 2.24 | (0.71, 7.10) | 0.170 | 2.08 | (0.65, 6.67) | 0.219 |

| 61–80 | 205 | 8820 | 23.24 | 2.39 | (0.76, 7.50) | 0.136 | 2.14 | (0.67, 6.90) | 0.202 |

| Obesity | 7 | 292 | 23.94 | 1.17 | (0.48, 2.84) | 0.731 | 1.09 | (0.44, 2.70) | 0.846 |

| Smoking | 3 | 167 | 17.94 | 0.35 | (0.05, 2.48) | 0.292 | 0.29 | (0.04, 2.07) | 0.215 |

| Comorbidities | |||||||||

| Alcohol disorders | 14 | 268 | 52.26 | 1.85 | (0.95, 3.61) | 0.072 | 2.11 | (0.99, 4.49) | 0.053 |

| COPD | 145 | 5328 | 27.21 | 1.17 | (0.89, 1.54) | 0.252 | 1.01 | (0.75, 1.34) | 0.973 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 5 | 117 | 42.74 | 2.29 | (0.85, 6.17) | 0.100 | 1.96 | (0.63, 6.04) | 0.244 |

| SLE | 4 | 22 | 180.15 | 8.83 | (2.82, 27.61) | <0.001 | 14.00 | (3.70, 53.19) | <0.001 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 10 | 396 | 25.22 | 0.91 | (0.41, 2.06) | 0.830 | 0.63 | (0.26, 1.54) | 0.314 |

| Cancer | 52 | 2227 | 23.35 | 1.12 | (0.78, 1.61) | 0.546 | 1.40 | (0.94, 2.06) | 0.095 |

| Psychosis | 56 | 829 | 67.59 | 2.55 | (1.76, 3.70) | <0.001 | 2.05 | (1.36, 3.09) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 202 | 5559 | 36.34 | 2.00 | (1.53, 2.62) | <0.001 | 1.50 | (1.10, 2.04) | 0.010 |

| Dementia | 3 | 29 | 102.74 | 1.72 | (0.24, 12.29) | 0.587 | 0.85 | (0.11, 6.53) | 0.877 |

| DCSI | |||||||||

| 0 | 83 | 5032 | 16.50 | 1.00 | (reference) | – | 1.00 | (reference) | – |

| 1 | 63 | 3072 | 20.51 | 1.23 | (0.82, 1.86) | 0.315 | 0.99 | (0.64, 1.54) | 0.979 |

| ≥2 | 191 | 6929 | 27.57 | 1.55 | (1.12, 2.15) | 0.008 | 1.37 | (0.89, 2.11) | 0.149 |

| Medications | |||||||||

| Sulfonylureas | 106 | 5173 | 20.49 | 0.99 | (0.75, 1.32) | 0.955 | 1.39 | (1.02, 1.88) | 0.037 |

| OAD number | |||||||||

| 0–1 | 327 | 14630.6 | 22.35 | 1 | (reference) | – | 1.00 | (reference) | – |

| 2–3 | 10 | 389.7 | 25.661 | 1.18 | (0.56, 2.51) | 0.6669 | 1.39 | (0.64, 2.99) | 0.406 |

| Insulin | 180 | 6096 | 29.53 | 1.37 | (1.05, 1.80) | 0.020 | 1.11 | (0.83, 1.48) | 0.494 |

| Corticosteroids | 3 | 158 | 18.99 | 1.34 | (0.43, 4.20) | 0.612 | 1.13 | (0.35, 3.68) | 0.841 |

- Abbreviations: aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; cHR, crude hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DCSI, Diabetes Complications Severity Index; IR, incidence rate, per 1,000 person-years; OAD, oral antidiabetic drug; PY, person-years; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

- a Multivariable analysis, including sex, age, comorbidities, CCI, DCSI, corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, statins, aspirin, insulin, item and number of oral antidiabetic drugs, duration of diabetes, and HbA1c check-up per year.

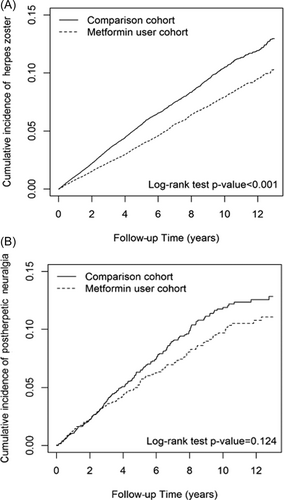

The Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that the cumulative incidences of herpes zoster and PHN were lower in metformin users than nonusers (Figure 2).

3.3 Cumulative dose of metformin

We assessed the association between the cumulative dose of metformin use and the risk of herpes zoster and PHN (Table 4). The HRs of three cumulative doses (<350, 350–1320, >1320 mg) of metformin use for the risk of herpes zoster were 1.53 (1.40–1.67), 0.94 (0.86–1.03), and 0.36 (0.33–0.40), respectively; for the risk of PHN were 1.96 (1.39, 2.76), 0.44 (0.27, 0.7), and 0.20 (0.11, 0.35), respectively, compared with metformin no-use. The higher cumulative dose of metformin was associated with a lower risk of zoster and PHN, but the lowest dose of metformin use (<350 mg) was associated with a significantly higher risk of herpes zoster and PHN.

| Variables | n | PY | IR | cHR | (95% CI) | p value | aHRa | (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herpes zoster | |||||||||

| Metformin no-use | 2153 | 194 643 | 1.11 | 1.00 | (reference) | – | 1.00 | (reference) | – |

| Cumulative dose of metformin (mg) | |||||||||

| <350 | 700 | 39 508 | 1.77 | 1.63 | (1.50, 1.78) | <0.001 | 1.53 | (1.40, 1.67) | <0.001 |

| 350–1320 | 602 | 57 205 | 1.05 | 0.98 | (0.89, 1.07) | 0.614 | 0.94 | (0.86, 1.03) | 0.215 |

| >1320 | 562 | 133 370 | 0.42 | 0.37 | (0.34, 0.41) | <0.001 | 0.36 | (0.33, 0.40) | <0.001 |

| Postherpetic neuralgia | |||||||||

| Metformin no-use | 257 | 6043 | 42.53 | 1.00 | (reference) | – | 1.00 | (reference) | – |

| Cumulative dose of metformin (mg) | |||||||||

| <350 | 47 | 1011 | 46.49 | 1.73 | (1.23, 2.42) | 0.001 | 1.96 | (1.39, 2.76) | <0.001 |

| 350–1320 | 20 | 2055 | 9.73 | 0.41 | (0.26, 0.66) | <0.001 | 0.44 | (0.27, 0.7) | <0.001 |

| >1320 | 13 | 4113 | 3.16 | 0.19 | (0.1, 0.33) | <0.001 | 0.20 | (0.11, 0.35) | <0.001 |

- Abbreviations: aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; cHR, crude hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DCSI, Diabetes Complications Severity Index; IR, incidence rate, per 1,000 person-years; OAD, oral antidiabetic drug; PY, person-years; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

- a Multivariable analysis, including sex, age, comorbidities, CCI, DCSI, corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, statins, aspirin, insulin, item and number of oral antidiabetic drugs, duration of diabetes, and HbA1c check-up per year.

4 DISCUSSION

Although vaccines and medications for herpes zoster are available, zoster and PHN pose significant healthcare challenges worldwide. Notably, this study showed that metformin use was associated with a significantly lower risk of herpes zoster and PHN. Furthermore, a higher cumulative dose of metformin was associated with a further lower risk of zoster and PHN. Metformin may provide a suitable option to reduce the burden of zoster and PHN in patients with T2D.

Chronic hyperglycemia in patients with diabetes can aggravate cellular oxidative stress and compromise innate and adaptive immune functions.16 Studies have demonstrated that patients with diabetes have about 1.3–1.6 times higher risk of herpes zoster than those without diabetes.4, 17 Lai et al.17 have performed a systemic review and meta-analysis, and showed that the incidence of herpes zoster ranging from 2.11 to 9.38 per 1000 person-years, with the overall incidence was 7.22 per 1000 person-years in patients with diabetes mellitus. The calculated incidence of herpes zoster in our study was 9.45 per 1000 person-years, which was slightly higher than the upper incidence (9.38 per 1000 person-years) of Lai's study. The difference of incidences between these two studies may be due to their dissimilar study population with different ethnicity, age, and immune function. Our study also showed that increasing age, COPD, autoimmune diseases, cancers, depression, and immunosuppressant therapy or insulin use had a higher risk of zoster. This finding is consistent with previous studies.1, 4 Older adults may be susceptible to herpes zoster due to a decline in immune function (immunosenescence). The use of chemotherapy in cancer patients or immunosuppressants in patients with autoimmune diseases and depression can compromise patients' cellular immunity and cause zoster.4, 18 People who receive insulin therapy may have long diabetes duration and suboptimal glucose control, which can comprise cell-mediated immunity, resulting in zoster.16 However, this study also showed that patients with psychosis had a lower risk of herpes zoster. The reason for this result is unclear. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to show that metformin use may reduce the risk of herpes zoster in patients with T2D, and a higher cumulative dose of metformin use can further lower the risk of zoster than no-use of metformin.

PHN is a complicated neuropathic pain that persists after the recovery of zoster. It can manifest as burning, electric shock-like, shooting, or evoked pain. PHN is difficult to treat, and less than half of patients experience a substantial reduction in suffering.2 Some patients have severe neuralgia that lasts for years and dramatically impairs their quality of life.2, 5 Currently, medications for pain relief are available, but there is no disease-modifying treatment for PHN.5 Few studies have reported risk factors for PHN. Studies have shown that severe and widespread zoster is more likely to produce PHN.1 Reports suggest that diabetes can also predispose to PHN.5 Our study showed that patients with autoimmune diseases, mental illness, and insulin users were more likely to develop PHN, probably because these people were more prone to herpes zoster or severe zoster that may cause PHN.4, 5 This study showed that metformin use was associated with a significantly lower risk of PHN, and a higher cumulative dose of metformin was associated with a more reduced risk of PHN.

Studies show that metformin can reduce the risks of pneumonia, tuberculosis, and sepsis; metformin can also decrease the severity and risk of mortality due to COVID-19 infection.8, 9 The mechanisms for metformin to decrease the risk of zoster and PHN may be multifactorial. (1) Metformin can reduce reactive oxygen species and C-reactive protein production, suppress nuclear factor-kappa B activation, decrease the secretion of interferon (INF)-α, INF-γ, tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin (IL)−1β, IL-6, IL-8, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; metformin can increase the levels of IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β.8-10, 19 Thus, metformin may alleviate systemic inflammation, amend the imbalance of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, and alleviate the reactivation of the VZV. (2) By suppressing signal transducer and activator of transcription-3, metformin can inhibit monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation, improve autophagy, and restrict viral multiplication.20, 21 (3) Metformin can activate AMPK and suppress the mammalian target of rapamycin to improve T cell differentiation and cell-mediated immunity.10 (4) AMPK activation can potentiate the expression of genes with antiviral properties (IFNs, IFN-stimulated genes), inhibit inflammatory mediators (tumor necrosis factor-α and CCL5), and enhance the innate antiviral response in virus-infected cells.22 (5) The activation of AMPK by metformin may inhibit virus-induced glycolysis, attenuate the phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase, resulting in the decreased source of energy and building blocks for viral replication.22

The strengths of this study are as follows: this is a nationwide and population-based study with minimal selection bias. The observational period of this study spans 18 years with the availability of comprehensive information on demographics, comorbidities, and medications, which can contribute to the investigation of outcomes. The clinical implications of this study may help reduce the burden of zoster and PHN in patients with T2D.

This study has some limitations. First, the National Health Insurance dataset does not contain data on biochemical tests, hemoglobin A1C levels, and immune functional tests, which may prevent an accurate evaluation of immune function and T2DM severity. This database also lacks information on body weight, diet, exercise habits, smoking, alcohol drinking, and family history. We searched for obesity, smoking, and alcohol consumption through the ICD codings. We matched clinically important variables, including sex, age, comorbidities, CCI, and medications, for maximal balance between the study and control groups. We also matched the items and number of OADs, insulin use, duration of T2D, and DCSI scores to balance the severity of T2D; and used the HbA1c check-up >2 times per year as a surrogate for hospital usage. Second, persons with severe hepatic and renal abnormalities may be concerned about lactic acidosis with metformin use. We, therefore, excluded patients on dialysis and those with hepatic failure to reduce the bias of confounding by indication. Third, the main participants in this study were Chinese; therefore, the results may not be applied to other ethnic groups. Finally, a cohort study is usually accompanied by certain unknown or unobserved confounding factors that affect the outcomes. Therefore, randomized controlled trials are needed to verify our results.

Unhealthy lifestyles and population aging have contributed to the increasing prevalence of T2D worldwide. Hyperglycemia compromises cell-mediated immunity in patients with T2D, making them susceptible to zoster and PHN. This study demonstrated that metformin use was associated with lower risks of herpes zoster and postherptic neuralgia in patients with T2D. The anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects of metformin need more research to repurpose it for a broader range of applications.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Fu-Shun Yen: study concept and design, drafting the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, study supervision. James Cheng-Chung Wei: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, technical and material support, study supervision. Hei-Tung Yip: data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; statistical analysis. Chih-Cheng Hsu: data analysis and interpretation, drafting the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and study supervision. Chii-Min Hwu: study concept and design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafting the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis; funding acquisition; technical or material support; study supervision.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Health Data Science Center, China Medical University Hospital for providing administrative, technical and funding support. This study is supported in part by Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial Center (MOHW110-TDU-B-212-124004), China Medical University Hospital (DMR-111-105). This work also received grants from the Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V101C-156, V108C-172, V109C-189) and the Ministry of Science and Technology, R.O.C. (MOST 110-2314-B-075-027-MY3). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. No additional external funding was received for this study. The corresponding authors had complete access to all data in the study and the final responsibility for the decision to publish.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study identified patients from the NHIRD and received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of China Medical University and Hospital [CMUH110-REC1-038(CR-1)]. The identifiable information of health providers and patients was encrypted before release to protect individual privacy. Informed consent was waived by the Research Ethics Committee.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data of this study are available from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) published by Taiwan National Health Insurance Administration (NHIA). The data utilized in this study cannot be made available in the paper, the supplemental files, or in a public repository due to the “Personal Information Protection Act” executed by Taiwan government starting from 2012. Requests for data can be sent as a formal proposal to the NHIRD Office (https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/cp-2516-3591-113.html) or by email to [email protected].