Monkeypox treatment: Current evidence and future perspectives

Abstract

As of September 11, 2022, 57 669 reports of monkeypox infection raised global concern. Previous vaccinia virus vaccination can protect from monkeypox. However, after smallpox eradication, immunization against that was stopped. Indeed, therapeutic options following the disease onset are of great value. This study aimed to review the available evidence on virology and treatment approaches for monkeypox and provide guidance for patient care and future studies. Since no randomized clinical trials were ever performed, we reviewed monkeypox animal model studies and clinical trials on the safety and pharmacokinetics of available medications. Brincidofovir and tecovirimat were the most studied medications that got approval for smallpox treatment according to the Animal Rule. Due to the conserved virology among Orthopoxviruses, available medications might also be effective against monkeypox. However, tecovirimat has the strongest evidence to be effective and safe for monkeypox treatment, and if there is a choice between the two drugs, tecovirimat has shown more promise so far. The risk of resistance should be considered in patients who failed to respond to tecovirimat. Hence, the target-based design of novel antivirals will enhance the availability and spectrum of effective anti-Orthopoxvirus agents.

1 INTRODUCTION

Recently, increased cases of monkeypox outside its endemic regions raised global concern. On May 13, 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) confirmed the first case of the current monkeypox outbreak in the United Kingdom (UK) patient who traveled from Nigeria. As of September 11, 2022, 57 669 cases of monkeypox have been reported.1, 2

Monkeypox is an Orthopoxvirus first detected in laboratory monkeys in 1958 and identified as a human pathogen in the 1970s. The virus primarily infected individuals in Western and Central Africa exposed to wild animals, causing skin lesions similar to smallpox. Nevertheless, the person-to-person transmission and the mortality associated with monkeypox infection are considerably lower than with smallpox. The mortality rate of monkeypox ranges from 1% to 11% in Africa, with a higher rate among children under 5 years old. The first monkeypox outbreak in the Western hemisphere was reported in the United States (US) in 2003 with no fatalities.3

It is well known that vaccination against smallpox with the vaccinia virus vaccine also offers strong protection against monkeypox. Once smallpox was eradicated, immunization against that was stopped, raising concerns about the subsequent rise in human monkeypox infection.4 The experience of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic highlights that any new viral behavior should be considered important. With a global increase in the numbers of monkeypox, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) warned about the global outbreak of monkeypox and stepped up its alert to a Level 2.5 Although monkeypox infection can be prevented with preexposure immunization, therapeutic options following disease onset are limited due to lacking approved medications. Given the rising concerns regarding the recent outbreak of monkeypox, this study reviewed its virology and treatment approaches.

2 VIROLOGY AND TRANSMISSION

Monkeypox is an enveloped double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (dsDNA) virus that belongs to the Orthopoxvirus genus of the Poxviridae family and uniquely replicates in the host cell cytoplasm. The Orthopoxvirus genus mainly includes the variola virus responsible for smallpox, the vaccinia virus used in the smallpox vaccine production, and the cowpox virus. The genome of Orthopoxviruses is 95% identical, and the mechanism is highly conserved. The two clades of monkeypox detected in various geographic regions of Africa differ in virulence. The clade isolated from Central Africa (Congo Basin) is more virulent, causing more severe disease than the West African isolate, which lacks some genes.6, 7

Recently, the WHO has given new names for the variants of the monkeypox virus, including Congo Basin as clade I and West Africa as clade II with two subclasses of Clades IIa and IIb. Currently, the Clade IIb is the most circulating subclass responsible for the 2022 global outbreak.8

Monkeypox has a quite large genome with approximately 196 858 base pairs that encode 190 open reading frames, constituting the material bulk required for replication of the virus in the cell cytoplasm.9 Unlike most double-stranded viruses that need the host cell's nuclear DNA-dependent ribonucleic acid (RNA) polymerase, poxviruses could encode their own transcription machinery to replicate in the cell cytoplasm.10

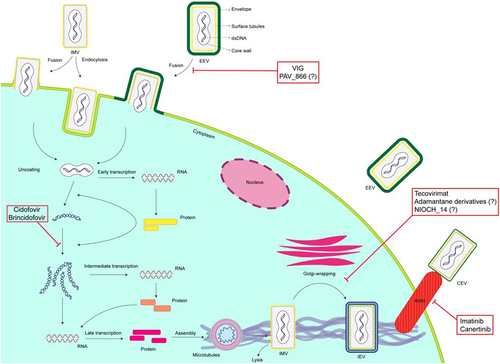

Two main pathways have been suggested for cell entry of the main infectious forms of poxviruses, including mature virion (MV) and extracellular enveloped virion (EEV). First, membrane fusion, which occurs at plasma neutral pH; and second, acidic pH endocytic pathway following caveolin- and clathrin-independent macropinocytosis or fluid phase endocytosis depending on actin dynamics.

The fusion relies on at least 11 nonglycosylated transmembrane proteins (A16, A21, A28, F9, G3, G9, H2, J5, L1, L5, and O3) that contribute to the formation of the entry fusion complex. These proteins are conserved in poxviruses suggesting the existence of a shared entry pathway. No known cellular receptors are identified yet for poxviruses cell entry. However, four proteins have been revealed to mediate the vaccinia virus attachment to the cell. Of them, A26 binds laminin glycoprotein, H3 and A27 bind to heparan sulfate, and D8 binds chondroitin sulfate, revealing the role of glycosaminoglycans. It is noteworthy that poxviruses cell entry can also occur in the absence of these cell surface polysaccharides.11, 12 Uncoating of the virus occurs in two steps; the outer membrane is removed, and the core is released into the cytoplasm, where the viral genes are expressed. The early genes encode the nonstructural protein required for viral DNA replication and synthesis of intermediate transcription factors. In the following steps, the transcription and translation of intermediate genes lead to the expression of late genes that encode early transcription factors, enzymes, and structural proteins. After virus assembly, MVs move on microtubules to the Golgi/endosomal compartment for the addition of two lipid layers to produce intracellular enveloped virions (IEVs). Cell-associated enveloped viruses, produced by the fusion of the IEVs' outermost membrane with the plasma membrane, induce actin tail formation by tyrosine kinases to egress the particle away from the cell to form EEVs responsible for the pathogenicity (outlined in Figure 1).13-15

It has been suggested that Golgi-associated retrograde protein subunits, and vacuolar protein sorting (VPS) genes, including VPS52 and VPS54, play a key role in monkeypox egress from infected cells and the formation of EEVs.16 Also, the F13L gene, a highly conserved gene among all Orthopoxviruses inhibited by tecovirimat, encodes the VP37 envelope protein, specific for the EEV. VP37 also plays a key role in the viral cellular transmission by the enveloped virions' attachment to or release from the cell membrane.17

Monkeypox is usually transmitted through contact with infected animals, such as prairie dogs, squirrels, monkeys, rats, rabbits, or mice. The route of infection with the virus might affect the severity of the illness. For example, studies from the US outbreak revealed that individuals bitten or scratched by infected animals showed more severe signs than those who just touched or noninvasively contacted infected animals. The person-to-person transmissibility of the virus is low, occurring through inhalation of large respiratory droplets (airborne transmission) with face-to-face contact that takes more than 3 h or through direct skin-to-skin contact.18-20 Subsequently, the virus infects either the respiratory epithelium or dermis. In the recent outbreak, reports of monkeypox DNA found in semen, urine, and saliva samples of infected patients raised concerns about the possibility of sexual transmission and the role of body fluids in virus transmission.21, 22 Lately, a case series of 528 polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-confirmed monkeypox cases across 16 countries revealed that 98% of patients were bisexual men or gay. The presence of the monkeypox DNA in the semen of 29 out of 32 patients supported the likelihood of sexual transmission. However, the viral transmission via seminal fluid needs further examination since it is unclear whether the viral DNA found in the samples can replicate.23 In another multicenter observational cohort on 181 cases with confirmed monkeypox, bisexual or gay men, men who have sex with men account for 92% of patients, suggesting that close contact might be the principal route of transmission in the current outbreak.24 However, in children infected with monkeypox, household contact was found to be the most common transmission route, raising concerns about extensive transmission.25

By disseminating through the lymphatic system, monkeypox could result in systemic infection and primary viremia. A second viremia leads to infection of the epithelium, causing skin and mucosal lesions. The virus transmissibility is directly correlated with the distance and duration of contact, the host immune response, the virus survival, and the extent of lesions.26, 27

The incubation period ranges from 4 to 17 days, with an average of 8.5 days. Patients are infectious within the first week of rash and should be isolated. The main clinical manifestations of infected patients were fever, chills, rash, myalgia, and lymphadenopathy. Patients might also report dysphagia, nausea, and vomiting, requiring hospital admission for hydration.1, 28, 29

3 MANAGEMENT

Infected patients with monkeypox mostly experience mild disease and recover without pharmacologic therapy. Patients might be at risk of severe dehydration and hospitalization for supportive care.29 Tecovirimat and brincidofovir got approval based on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Animal Efficacy Rule for the treatment of smallpox. Although similar virology of orthopoxviruses might make their use rational in monkeypox, in the recent study by Adler et al., brincidofovir treatment was stopped due to the drug-related side effect when administered to three people with monkeypox.30, 31

Also, the present clinical investigational studies only include tecovirimat as the agent for monkeypox intervention (NCT00728689 and NCT02080767).32, 33

We classified the studies according to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Recommendation Classification System.34 This system evaluates therapeutics according to the class of recommendation (strong = I, IIa = moderate, IIb = weak, and III = moderately no benefit or strongly harmful) and level of evidence (A = high quality randomized clinical trials, B-R = moderate-quality randomized clinical trial, B-NR = moderate-quality nonrandomized clinical trial, C-LD = limited data, and C-EO = expert opinion). Data about the potential drugs used against monkeypox are presented in Table 1.

| Antiviral | Studies on monkeypox | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name (route of administration) | Approved for smallpox | Dosing for smallpox | Serious adverse effects | Author, year | Model (sample size) | Outcomes | COR/LOE |

| Cidofovir (IV) | No | Not applicable | Nephrotoxicity, neutropenia, teratogenic/carcinogenic | Stittelaar et al., 2006 | Monkey (34) | Reduced mortality and skin lesions | III/C-LD |

| Huggins et al., 1998 | Monkey | Reduced mortality and improved clinically and laboratory signs of disease | |||||

| Huggins et al., 2004 | Monkey | Complete protection without any signs of disease | |||||

| Brincidofovir (oral) | Yes | <10 kg: 6 mg/kg, 10–48 kg: 4 mg/kg, ≥48 kg: 200 mg once weekly for two doses | GI effects, hepatotoxicity | Hutson et al., 2021 | Prairie dog (21) | Similar survival rate compared to the placebo | IIa-LD |

| Adler et al., 2022 | Human (3) | All patients discontinued the drug due to increased liver enzymes | |||||

| Tecovirimat (oral, IV) | Yes | Oral; 13–25 kg: 200 mg, 25–40 kg: 400 mg, 40–120 kg: 600 mg every 12 h for 14 days; ≥120 kg: 600 mg every 8 h for 14 days; IV; 3–35 kg: 6 mg/kg, 35–120 kg 200 mg every 12 h infused over 6 h for up to 14 days | Headache, injection site reactions | Berhanu et al., 2015 | Monkey (32) | Improved survival rate and clinical signs | I-LD |

| Adler et al., 2022 | Human (1) | Decreased duration of hospitalization | |||||

- Abbreviations: COR/LOE, class of recommendation/level of evidence; GI, gastrointestinal; IV, intravenous; LD, limited data.

3.1 Cidofovir

Cidofovir ([S]-1-[3-hydroxy-2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl]cytosine) is the first acyclic nucleoside phosphonate approved for the treatment of human cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Cidofovir undergoes two-step phosphorylation in the cell to form its active metabolite, cidofovir diphosphate (CDVpp), which can inhibit viral replication. CDVpp prevents the incorporation of deoxycytidine triphosphate in viral DNA by interacting with viral DNA polymerase. Accordingly, the drug terminates the viral DNA elongation. Notably, host cell-dependent phosphorylation of cidofovir makes it active against viruses resistant to acyclovir and ganciclovir.35, 36

Although cidofovir is not approved for infections caused by Orthopoxviruses, it could be used during an outbreak under an appropriate regulatory system, such as an Emergency Use Authorization or Investigational New Drug.37 Several studies showed in vitro efficacy of cidofovir against a wide spectrum of poxviruses, including monkeypox, smallpox, vaccinia, camelpox, cowpox, ectromelia, orf virus, and molluscipoxvirus.38 Limited evidence suggested that cidofovir could reduce smallpox vaccine complications.39

In a study by Stittelaar et al., monkeypox responds better to antiviral therapy than smallpox postexposure vaccination.40 They assigned 34 macaques in six groups to receive treatment 24 h after infection with monkeypox. As the control arm, Group 1 received only the supportive treatment (n = 6). Group 2 received a vaccinia virus-based smallpox vaccine (n = 6). Group 3 (n = 6) and 4 (n = 6) received five- and six-dose regimen of intraperitoneal cidofovir 5 mg/kg every other day, respectively. Groups 5 (n = 4) and 6 (n = 6) received five- and six-dose regimens of intraperitoneal cidofovir analog, High Point Urban Area Metropolitan Planning Organization (HPMPO)-DAPy, 5 mg/kg every other day, respectively. No animals in the control group survived within 15 days of infection. In contrast, cidofovir prevented death and severe disease in 9 out of 12 animals (5 in Group 3 and 4 in Group 4). The survival rate of animals treated with cidofovir was significantly higher than the control group and vaccinated animals (p < 0.05). Also, the viral load in animals treated with cidofovir (Groups III and IV) was significantly decreased compared with the vaccinated and control groups (p = 0.002 and 0.021, respectively). HPMPO-DAPy administration was also associated with a lower viral load than all other groups (p < 0.005–0.041). The six-dose regimens of cidofovir and HPMPO-DAPy were associated with a further reduction in plasma viral loads than the five-dose regimens (cidofovir, p = 0.002; HPMPO-DAPy, p = 0.007). Although this study supported the use of cidofovir in monkeypox treatment, the authors suggested that the drug should be optimized for use in humans.40

In two other studies, cidofovir administration (5 mg/kg before or up to 2 days after infection) decreased the mortality in monkeys infected with monkeypox.41, 42

Because of its low bioavailability, cidofovir is administered intravenously. It is extensively excreted unchanged in the urine via active secretion and glomerular filtration. The elimination half-life of cidofovir is low (2 h). However, it has prolonged antiviral effects resulting from the long half-life of diphosphorylated metabolites, which reaches 65 h.43

Nephrotoxicity is the most critical adverse effect of cidofovir, indicated by proteinuria, glucosuria, necrosis of the proximal renal tubules, and elevated serum creatinine. Cidofovir-associated renal dysfunction is dose-related and is reversible in the majority of patients after cidofovir discontinuation. Nonetheless, a few cases of end-stage renal disease have been reported in patients with the human immune deficiency virus.44, 45 In patients with renal dysfunction-related cidofovir who are on therapy, dosage adjustments or discontinuation of the drug is necessary.46

The human organic anion transporters (hOAT), especially Type 1, play a key role in the secretion and accumulation of cidofovir in the proximal renal tubules, leading to nephrotoxicity.47 Administration of probenecid, an inhibitor of hOAT, and saline hydration reduce the risk of nephrotoxicity.43 Of note, probenecid should be used with caution in pregnant women, children, and patients with a history of sulfa drug allergy.

Other adverse effects of cidofovir include neutropenia, uveitis, iritis, nausea, vomiting, fever, and skin rash. Also, cidofovir has been associated with mammary adenocarcinoma in rats, suggesting it may also be carcinogenic to humans.46

3.2 Brincidofovir

Brincidofovir is formed by binding a lipid chain, 3-hexadysiloxy-1-propanol, to the phosphonate part of cidofovir. The lipid chain was then cleaved by the cell phospholipase to form the active metabolite cidofovir.48

In 2021, the drug was approved for use in infants, children, and adults with smallpox based on the “Animal Rule.”31 According to this rule, the FDA would approve drugs based on well-designed animal efficacy trials when the drug prevents or treats fatal diseases and when clinical trials involving humans are not ethical or possible. The recommended doses for brincidofovir are based on patients' weight and administered orally once weekly. Notably, the longer duration of treatment was associated with an increased risk of mortality.49 The advantages of brincidofovir over cidofovir were higher oral bioavailability and potency, resulting from a lipid chain addition that facilitates drug uptake into the cells. Importantly, brincidofovir is not a hOAT1 substrate and does not accumulate in the proximal renal tubules. Also, the peak plasma concentration of cidofovir persists at low levels after the administration of brincidofovir. Therefore, unlike cidofovir, brincidofovir-related nephrotoxicity is uncommon, and dose adjustments are not strictly necessary in renal impairment.50

Hutson et al. evaluated the efficacy and pharmacokinetics of brincidofovir in prairie dogs infected with monkeypox. The animals were administered a three-dose regimen of brincidofovir (20 mg/kg, followed by two doses of 5 mg/kg every 48 h) either 1 day before infection (n = 7), on the day of infection (n = 7), or 1 day after infection (n = 7). The survival rate of animals who received brincidofovir 1 day before infection (57%) was higher than those treated with brincidofovir on the day of infection (43%) or 1 day after infection (29%). However, the difference did not reach statistical significance between the treatment groups and the placebo group, with a survival rate of 14% (p = 0.42). The lower efficacy of brincidofovir observed in this study might be due to the suboptimal drug exposure in prairie dogs.51 In contrast, administering 20 mg/kg brincidofovir 3 days after infection with rabbitpox was associated with a 100% survival rate when administered as a single-, two-, or three-dose regimens. However, no animal in the placebo group could survive.52

Brincidofovir is eliminated predominantly via hepatic metabolism, through which metabolites are equally excreted in feces and urine within 3 days following oral use.

In a case report of a 17-year-old immunosuppressed adolescent, disseminated cowpox infection, confirmed by PCR and electron microscopy, led to death despite receiving vaccinia immune globulin (VIG) and brincidofovir. At first, the patient received cidofovir 2 days after the cowpox diagnosis, which was changed to brincidofovir later.53 The delay in antiviral initiation and not mentioning the doses of medications limit the interpretation of results.

Another case report study describes a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia and ACAM2000-induced progressive vaccinia who had received topical and oral tecovirimat following infusions of intravenous VIG (VIGIV). While receiving treatment, he was diagnosed with sepsis that required corticosteroid administration. He also experienced satellite lesions with high viral copies in blood detected by PCR, leading to brincidofovir initiation. Totally, 73 days (75 g) of oral tecovirimat and of 68 days of topical tecovirimat, 341 vials of VIGIV, and 6 weekly doses of brincidofovir (700 mg) were administered. Unlike brincidofovir, resistance to tecovirimat was observed following prolonged subtarget systemic treatment levels and concurrent topical formulation usage. Although the treatment led to Orthopoxvirus being undetected by immunohistochemical staining or PCR, it is challenging to determine the influence of any intervention.54

Gastrointestinal adverse effects, manifested by nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration, and subsequent weight loss, are the dose-limiting toxicity of oral brincidofovir that might result from the drug's high concentrations in the small intestine.50 It has been shown that the daily administration of brincidofovir led to enteritis, enteropathy, and gastropathy in monkeys and mice. However, further studies in animal models did not report dose-limiting gastrointestinal toxicity with twice-weekly regimens of oral brincidofovir, showing a relation between the dose/frequency of dosing and the brincidofovir-associated gastrointestinal effects.

Hepatotoxicity, diagnosed by increased liver aminotransferases, is the main adverse effect of brincidofovir, which led to drug discontinuation in all recipients with monkeypox.55 The rise in liver enzymes is generally reversible, and there is no correlation between the dose concentration of brincidofovir and hepatotoxicity.48, 49 Liver laboratory abnormalities, primarily alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase, and bilirubin elevations, have been observed in clinical trials. When different doses were evaluated in a Phase 2 study of brincidofovir, ALT elevations were more common in patients who received doses higher than 200 mg per week.56

Regarding the drug interactions, OATP1B1/1B3 inhibitors, such as gemfibrozil, cyclosporine, and rifampin, might increase the serum concentrations of brincidofovir. If concomitant use is required, these drugs should be administered at least 3 h following brincidofovir with monitoring of adverse effects.49, 57

3.3 Tecovirimat

After oral tecovirimat, the intravenous formulation was also approved in May 2022 to treat smallpox in adults and children.30, 58 Besides smallpox, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) authorized tecovirimat use in monkeypox and cowpox infections.59 Tecovirimat was also administered as an emergency investigational drug to treat complications related to the smallpox vaccine, such as eczema vaccinatum observed in a seriously ill child who also received VIG.60 Tecovirimat inhibits the release and maturation of the virus by targeting the viral envelope protein. The drug blocks the function of the Orthopoxvirus VP37 envelope-wrapping protein and prevents its interaction with host cell Rab9 guanosine triphosphatase and TIP47, inhibiting the production of enveloped virions required for virulence.61

While the mechanism by which tecovirimat inhibits poxvirus replication through F13 is not fully understood, a few recent studies revealed various functions of F13. F13 is crucial for the formation of wrapped viruses (IEV and EEV). It has been suggested that F13 uses the retrograde transport pathway to form the viral wrapping membrane.62 Second, it was shown that F13 controls the amounts of glycoproteins incorporated in the outer extracellular virion membrane at optimum levels required for infectivity.63 Also, recent evidence suggested a postenvelopment function for F13, through which F13 enhances the low pH-dependent dissolution of extracellular virion membrane, leading to rapid cell entry kinetics.64 Recently, molecular simulation analysis identified the structures of monkeypox F13 protein and its key residues associated with tecovirimat. The molecular docking results confirmed the efficacy of tecovirimat against both variola and monkeypox viruses.65

Tecovirimat was detected by screening more than 350 000 chemical compounds, which inhibited all Orthopoxviruses investigated in vitro without affecting other viruses.66 Although the risk of resistance against tecovirimat is relatively low, amino acid changes in the target VP37 protein can substantially decrease drug efficacy.67 According to the exposure-response correlation in previous clinical pharmacokinetic studies for various doses and animal models, simulation and model studies suggested that tecovirimat at doses of 600 mg every 12 h would result in high drug exposure in humans.68

Berhanu et al.69 included 32 monkeys to evaluate the efficacy of tecovirimat and ACAM2000 smallpox vaccine administration 3 days after monkeypox infection. They showed that postexposure administration of ACAM2000 alone did not decrease mortality or severe illness. In contrast, all animals treated with 10 mg/kg oral tecovirimat for 14 days showed a significant improvement in survival rate and clinical signs. Another investigation evaluated whether delayed treatment with tecovirimat in 21 symptomatic monkeys with lesions could protect animals from mortality.69 Their results showed that 10 mg/kg of tecovirimat administered on Day 4 or 5 following exposure was associated with an 83% survival rate. In contrast, initiating the drug 6 days after exposure led to a survival rate of 50%.

This study highlighted that the humoral immune response against monkeypox infection was not fast enough with vaccination to prevent mortality. Therefore, tecovirimat is recommended within this period to decrease the viral load and overcome this limitation.

Another study by Grosenbach et al.70 evaluated the efficacy of different regimens of tecovirimat in nonhuman primate and rabbit models of smallpox. Tecovirimat was administered at doses ranging from 20 to 120 mg/kg in rabbits and 0.3 to 20 mg/kg in nonhuman primates for 14 days, initiated 4 days following the infection. All rabbits in the placebo group died of rabbitpox infection, and 1 of 20 nonhuman primates that received a placebo survived the monkeypox infection. Tecovirimat at doses from 3 to 10 mg/kg in nonhuman primates resulted in a survival rate of 95% compared with 5% in the placebo group. The comparison of different treatment periods for 10 mg/kg tecovirimat showed that the survival rate with 3-, 5-, and 10-day regimens were 50%, 100%, and 80%, respectively. Although 40 mg/kg of tecovirimat provided full protection in rabbits, nonhuman primates achieved greater exposure values, suggesting that nonhuman primates were better models for human smallpox.

To assess the safety and pharmacokinetics of the drug, 449 individuals were included to receive either 600 mg tecovirimat twice daily (n = 359) or a placebo (n = 90) for 14 days. Individuals were followed up for 28 or 45 days if they experienced events on Day 28. Totally, 37.3% of patients in the tecovirimat group and 33.3% in the placebo group reported adverse events, leading to drug discontinuation in 1.7% and 2.2% of patients, respectively. One patient treated with tecovirimat died of nondrug-related pulmonary embolus.70 Intravenous tecovirimat is contraindicated in patients with severe kidney failure, indicated by creatinine clearance below 30 ml/min since it contains excipient hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin eliminated by glomerular filtration.

Tecovirimat weakly inhibits the liver cytochrome P450 2C8 enzyme and causes an increase in serum concentration of repaglinide and subsequent hypoglycemia. Hence, blood glucose monitoring should be considered during the coadministration of tecovirimat and repaglinide. Also, tecovirimat is the weak inducer of cytochrome 3A4 and decreases the serum levels of midazolam, which may require dose adjustment.71

In the recent UK report of seven confirmed monkeypox patients, three patients received 200 mg brincidofovir once weekly, and one received tecovirimat 600 mg twice daily for 14 days.55 All patients treated with brincidofovir discontinued the drug over the raised liver enzymes. Tecovirimat was associated with a shorter hospitalization length than all other patients (mean days; tecovirimat, 10 days; brincidofovir, 29.3 days; no treatment, 24.6 days). Of note, tecovirimat was initiated 5 days after the appearance of skin lesions, whereas brincidofovir was started 1–2 days later. The small sample size and interpatient variations might also limit the interpretation of the results.

Another study evaluated the compassionate use of tecovirimat in 25 patients with PCR-confirmed monkeypox.72 The median age of patients was 40.7 years (range 26–76), and all were men. The mean time between symptom onset and tecovirimat initiation was 12 days, ranging from 6 to 24 days. Patients received weight-based dosing of tecovirimat every 8 or 12 h for 7 days, which was extended for 21 days in one patient due to his deteriorating clinical status. Monkeypox-related lesions were recovered in 40% and 92% of patients after 7 and 21 days of treatment initiation, respectively. Tecovirimat was well-tolerated with no adverse effects leading to drug discontinuation. Due to the lack of a placebo group and variable duration between symptom onset and treatment, the results should be interpreted with caution since data might be attributed to the self-limiting feature of the disease.

3.4 Vaccinia immune globulin

The VIGIV, obtained from the human plasma of smallpox-vaccinated individuals, was approved by the US FDA to treat complications resulting from replication-competent smallpox vaccines, such as progressive vaccinia eczema vaccinatum, severe generalized vaccinia, and certain aberrant infections with vaccinia virus.73

Evidence regarding the efficacy of VIG in monkeypox treatment or postexposure prevention is lacking. The postexposure administration of VIG might be considered in immunosuppressed patients for whom vaccination is contraindicated.54

Recently, the CDC has issued an expanded access system allowing the administration of VIGIV in Orthopoxviruses outbreaks, such as monkeypox.74 Some precautions should be taken into account when using the VIGIV. For example, its interference with nonglucose-specific blood glucose monitoring systems might lead to false higher glucose levels, leading to untreated hypoglycemia. Of note, renal function should be monitored during the administration of VIG, particularly in high-risk patients.73

The literature review of 25 studies assessed the efficacy of VIG in the treatment of smallpox vaccine complications or prevention of smallpox in those with close contact.75 Although no clinical trial was included, VIG appears to decrease the morbidity and mortality caused by progressive vaccinia, eczema vaccinatum, and possibly severe generalized vaccinia and ocular inoculation in the absence of keratitis. VIG was not effective against postvaccinial encephalitis since it was suggested to be an immune-mediated complication rather than a direct vaccine-induced infection of the central nervous system. Although not indicated for this complication, a randomized trial of over 106 000 showed that VIG significantly decreased the rate of postvaccinial encephalitis compared with the control group (3 vs. 13 cases).76

4 INVESTIGATIONAL ANTIVIRALS

The target-based design of novel antivirals will enhance the availability and spectrum of effective antiorthopoxvirus agents. To date, several compounds have been reported to be effective against Orthopoxviruses in vitro (Table 2). However, their efficacy and safety in the setting of monkeypox are uncovered and require further preliminary and clinical studies. Orthopoxvirus VP37 protein, inhibited by tecovirimat, is an attractive therapeutic target since it has no homologs among human proteins. Adamantane derivatives showed potential inhibitory effects on VP37 using virtual screening and molecular docking. Subsequent synthesis and in vitro analysis showed that these compounds could inhibit vaccinia virus replication with 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50) between 0.133 and 0.515 μm.77 Although VP37 is highly conserved among Orthopoxviruses, the extensive assessment of compounds revealed that the cowpox virus has the least sensitivity to adamantane derivatives compared with the vaccinia virus and mousepox virus.

| Compound name | Cell | Virus | Virus concentration | Efficacy | Cytotoxicity | Cellular target |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adamantane derivatives77 | Vero | VV, CPXV, and ECTV | 6.85 log PFU/ml | IC50VV, 0.133–0.515 μm; IC50CPXV, 0.928– 32.9; IC50ECTV, 0.492–11.1 | CC50 2.5–309.3 µm |

P37 |

| NIOCH-1478 | Vero | MPXV (central African strain V79-1-005), ECTV, and VARV (India-3a, 6-58, Congo-9, and Butler) | 5.6–6.7 log10 PFU/ml | IC50MPXV, 0.013 μg/ml; IC50ECTV, 0.011; IC50VARV, 0.001–0.004 |

TC50 > 100 µg/ml | Inhibition of the formation of different enveloped forms of the virus (intracellular, cell-associated, and extracellular) |

| (+)-camphor and (−)-borneol derivatives79 | Vero | VARV, CPXV | 5.6–6.1 log10 PFU/ml | IC50VARV, 8.8–215.1 µm; IC50CPXV, 6.3–177.6; IC50CPXV, 3.4–168.8 | CC50 50.7–2904.9 µm |

Block viral replication |

| PAV-866 derivatives80 | HeLa | VARV | MOI of 0.4 | EC50, 0.29–2.53 μm. | Decrease viral binding, fusion, entry, and gene expression | |

| Imatinib mesylate14 | BSC-40 | VV (WR), MPXV (1979-ZAI-005), or VARV (BSH, SLN) | MOI of 0.1 | Reduced the amount of VARV-BSH (65%), VARV-SLN (84%), MPXV (22%), and VV-WR (94%) | Block viral release | |

| Resveratol81 | HeLa, HFF |

VACV, MPXV (WA, ROC) | MOI of 1 | IC50VARV, 4.72; IC50MPXV (WA), 12.41; IC50MPXV (ROC), 15.23 |

CC50, 157.75 | Inhibition of DNA synthesis and subsequently post-replicative gene expression |

| Interferon-B82 | HeLa, NHDF, pretreated 24 h before infection | MPXV (Zaire) | MOI of 5 | Viral titers were reduced by 91% with 2000 U/ml in HeLa cells and 95% by 25 U/ml in NHDF cells | No | Inhibition of production, release, and spread by inducing MxA |

| Mitoxantrone83, 84 | BSC-40 | VV (WR) | MOI of 0.01 | IC99, 0.25 (48 h) | >5 µm | Inhibition of late protein synthesis |

| BSC-1 | CPV, MPXV | MOI of 1 | EC50MPXV, 0.25 μm; EC50CPX, 0.8 μm |

16 μm | ||

| Ribavirin85 | Vero, LLC-MK2 | MPXV, VARV (BSH, YAM, GAR) | MOI of 0.1 | IC50MPXV, 5.9 (Vero), 4.1 μg/ml (LLC-MK2); IC50VARV (BSH), 18.4 (Vero), 2.1 μg/ml (LLC-MK2); IC50VRV (YAM), 15.8 (Vero), 3.4 μg/ml (LLC-MK2); IC50VRV (GAR), 17.0 (Vero), 3.6 μg/ml (LLC-MK2) |

TC50 > 100 μg/ml (Vero and LLC-MK2) | Inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase inhibitor |

| Tiazofurin85 | Vero, LLC-MK2 | MPXV, VARV (BSH, YAM, GAR) | MOI of 0.1 | IC50MPXV, 20.0 (Vero), 5.2 μg/ml (LLC-MK2); IC50VARV (BSH), 22.6 (Vero), 5.5 μg/ml (LLC-MK2); IC50VRV (YAM), 21.4 (Vero), 3.9 μg/ml (LLC-MK2); IC50VRV (GAR), 19.8 μg/ml (Vero), 6.1 μg/ml (LLC-MK2) |

TC50, 90 (Vero) and >100 μg/ml (LLC-MK2) | Inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase inhibitor |

- Abbreviations: CPXV, cowpox virus; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; ECTV, ectromelia virus; HFF, human foreskin fibroblast; IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration; MOI, multiplicity of infection; MPXV, monkeypox virus; NHDF, normal human dermal fibroblasts; PFU, plaque-forming unit; TC50, median toxic concentration; VACV, vaccinia virus; VARV, variola virus; VV, vaccinia virus.

NIOCH-14 is another VP37 inhibitor, which showed antiviral activities against Orthopoxviruses in vitro and in vivo studies. It has been shown that administration of oral NIOCH-14 (10 mg/g 1 day before and 2 h after infection for 6 days) to mice infected with monkeypox at a dose of 3.4 log10 plaque-forming unit (PFU) significantly decreased the number of infected mice (0.0% vs. 100%) and viral load in lung tissue (1.7 vs. 4.9 log10 PFU) as compared with the control group 7 days after infection. Also, marmots treated with NIOCH-14 did not show the disease symptoms 7 days after infection. NIOCH-14 is a tricyclodicarboxylic acid derivative converted to its active metabolite tecovirimat, the condensed pyrroledione derivative.78

Several studies revealed that monoterpenoid derivatives block viral replication. For example, camphor and borneol derivatives showed activity against Orthopoxviruses, such as variola and vaccinia.79 However, data regarding their efficacy on the monkeypox virus is limited.

Methylene blue derivative, PAV-866, showed in vitro virucidal activity against various Orthopoxviruses, including the monkeypox virus, regardless of whether particles had entered the cells. PAV-866 and its derivatives blocked the binding, fusion, and entry of the virus before it could infect the cells.80

Orthopoxviruses' requirement for the Src and Abl family tyrosine kinases to form actin cells proposed a hypothesis that tyrosine kinase inhibitors might block the viral release from the cell. Evidence that supported this hypothesis showed that Abl inhibitor, imatinib mesylate, inhibited the release of EEV in cells infected with monkeypox and protected mice from mortality caused by the vaccinia virus. Mice were administered imatinib mesylate at a dose of 200 mg/kg/day 1 day before infection, at the time of infection, or 1 to 2 days after infection with the 100% lethal dose of vaccinia virus (2 × 104 PFU). While preinfection administration of the drug led to a 100% survival rate, significant improvement was also seen in the survival rate of mice that received the drug either on the day of infection or 1 day later. Although dasatinib, an inhibitor of both Abl and Src, showed a potent in vitro inhibitory effect on monkeypox, it was associated with immunosuppression in mice, limiting its administration as a therapeutic agent.14

A newly discovered CRISPR–Cas9 could significantly reduce the monkeypox titers in vitro by breaking dsDNA at particular genomic loci recognized by single-guide RNAs.86

A novel pyridopyrimidinone compound, CMLDBU6128, identified through screening of a diversity-oriented synthesis library, showed antiviral activity against Orthopoxviruses by inhibiting intermediate and late gene expression. The IC50 of CMLDBU6128 on the vaccinia reporter virus was 5.3 μm 12 h following infection in both A549 and HeLa cells. Moreover, CMLDBU6128 reduced monkeypox (strain Zaire 1979) viral yields by 2.5 log, A549 cell line. The suggested mechanism by which CMLDBU6128 could block viral replication was targeting viral RNA polymerase large subunit gene, J6R. However, A954V or V576G mutation in J6R led to resistance to CMLDBU6128, increasing the viral yields by 10- and 40-fold, respectively.87

Another study used Gaussia luciferase reporter assay to select hits with inhibitory effects on vaccinia virus replication. Overall, 142 compounds were effective in a dose-dependent manner at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 and 2 for HeLa cells with no or low effects on cell viability. The hits were identified according to their capability to inhibit late gene expression. They were detected by luciferase inhibition 24 h postinfection with a reporter vaccinia virus, vLGluc, compared with cytosine arabinoside (AraC) positive control. The percentage of luciferase inhibition ranged from 50.4% to 100.0% for compounds at a dose of 10 µm in MOI 0.01. The most identified hits were nucleoside analogs, heat shock protein 90, and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Of them, 35 compounds were FDA approved for viral or other diseases, including anagrelide approved for thrombocythemia, floxuridine used for colorectal cancer, and desmethyl erlotinib approved for renal cell carcinoma and lung and pancreatic cancer. Three compounds from JAK-STAT3 inhibitors, including niclosamide (1 µm), AZ960 (3 µm), and SC144 (1 µm), significantly reduced the viral titers in normal human dermal fibroblasts (NHDF) cells 8 h postinfection compared with the negative control.88 Most identified hits have no specific antiviral effects that might lead to various adverse effects, limiting their use in monkeypox treatment. However, modifying the structures of hit compounds can be used in new drug discovery strategies, particularly in outbreak situations.

Another study investigated resveratrol efficacy on monkeypox in HeLa cells at an MOI of 1.81 The results showed that 50 μm resveratrol decreased the yield of monkeypox-WA and monkeypox-ROC clades by 195- and 38-fold, respectively. The IC50 was 12.41 μm for the WA strain and 15.23 μm for the ROC strain. Resveratrol has been revealed to decrease monkeypox replication in amounts comparable to the well-known Orthopoxvirus inhibitor, AraC.

Johnston et al.82 reported that interferon-β (IFN-β) induces the expression of the antiviral protein MxA in infected HeLa cells, leading to a significant decrease in the production, release, and spread of monkeypox by 1log 24–48 h postinfection. In addition, IFN-β significantly reduced infectious monkeypox in a primary cell line, NHDF, which more closely resembles the in vivo condition than immortal cell lines. Pretreatment with increasing doses of IFN-β (0–5000 U/ml) 24 h before infection showed 95% and 99% reduction in viral titers, with the lowest dose (25 U/ml) and concentrations higher than 1000 U/ml, respectively. In HeLa cells, this degree of inhibition was not observed even with the high doses of IFN-β (5000 U/ml), indicating that monkeypox susceptibility to IFN-β is elevated in primary cells.

By screening a library of existing medicines, 13 compounds were discovered to inhibit vaccinia virus multiplication at noncytotoxic dosages.83 Several agents, such as mycophenolic acid, ancitabine, and inhibitors of eukaryal protein synthesis (cycloheximide, anisomycin, emetine, and cephaeline) were among the detected hits. New agents with antipoxvirus activity include cardiac glycosides, lycorine, and mitoxantrone. Among identified agents, mitoxantrone was unique in inhibiting virion assembly without affecting the virus's late protein. Despite promising findings in cell culture, mitoxantrone showed no activity in mice infected with a lethal dose of vaccinia virus (105 PFU).83 Three doses of mitoxantrone were investigated 1 day after infection, including 5 mg/kg/day for one dose, 4.25 mg/kg/day for 2 days, and 1.25 mg/kg/day for 4 days. Mice in positive control and placebo groups received cidofovir at 100 mg/kg/day for 2 days and saline, respectively. While all mice survived in the cidofovir group, 85% and 100% died in the placebo and mitoxantrone groups, respectively. The mean duration between infection and death was 7.0, 8.2, and 7.4 days for 1-, 2-, and 4-day regimens of mitoxantrone, respectively.

Mitoxantrone also showed in vitro activity against cowpox and monkeypox, with high synergistic activity in combination with cidofovir against cowpox.84 Also, in vivo administration of mitoxantrone at doses of 0.25 mg/kg or 0.5 mg/kg in C57Bl/6 mice 1 day after intraperitoneal challenge with the cowpox virus significantly increased the median time to death (from 7 days in the control group to 9 days [p = 0.0015] and 12 days [p = 0.0005], respectively). However, mitoxantrone was not beneficial in intranasally-infected BALB/c mice, suggesting that the effect may be affected by the route of infection and mice strain.

Tiazofurine and ribavirin are inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase inhibitors investigated in several viral diseases. Unlike tiazofurine, ribavirin is an approved antiviral for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C and respiratory syncytial virus in oral and inhalation formulations, respectively. However, evidence regarding their efficacy against DNA viruses is still lacking. The inhibitory effects of tiazofurin and ribavirin on monkeypox and variola virus replication were demonstrated in an in vitro study. However, cowpox and vaccinia virus showed minimal sensitivity for both drugs. Notably, the resulting IC50s depended on the cell type and virus strain.

In mice models intranasally infected with 3 × 105 PFU of cowpox, subcutaneous ribavirin at daily doses of 100 mg/kg for 5 days resulted in a 100% survival rate compared with the placebo group, in which all animals died. However, it showed no survival benefit in mice challenged with a high virus dose (3 × 106).85 In a case report of a 67-year-old patient with progressive vaccinia, administering intravenous ribavirin, followed by VIG, showed beneficial effects. However, the contribution of each drug to study outcomes cannot be elucidated.89

Rifampin is an antitubercular agent that binds to the DNA-dependent RNA polymerase beta subunit, inhibiting bacterial RNA synthesis.90 It was revealed that rifampin could block the D13L protein, inhibiting viral replication.91 Recently, molecular screening of the FDA-approved drugs showed a high ability for rifampin to bind monkeypox D13L protein, suggesting it is a potential target that requires further investigation.92 The use of rifampin might be limited due to the great risk of mutation in the D13L gene, making viruses resistant.93

5 PREVENTION

Previous vaccinia virus vaccination is highly effective against monkeypox (more than 85%). Two vaccines might be effective in preventing monkeypox disease, including modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) and ACAM2000. The in vivo studies regarding their efficacy against monkeypox and clinical data are provided in Table 3.94-97

| Name | Type | Media for propagation | In vivo studies against monkeypox | Phase III surrogate efficacy results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model/number | Challenge virus dose | Outcomes | ||||

| ACAM2000 | Live replication-competent | Vero cells | Macaques/24 | 3.8 × l07 PFU/ml, 2 months after vaccination | Prevented animals from showing infection significant signs.94 | Highly induced neutralizing antibodies and take-rates.95 |

| MVA | Live replication-deficient | Chicken embryo fibroblast cells | Macaques/35 | 106/5 ml or 107/5 ml PFU, 15 weeks after vaccination | Protected animals from infection symptoms and reduced viral load.96 | Highly induced neutralizing antibodies without lesion formation.97 |

- Abbreviations: MVA, modified vaccinia Ankara; PFU, plaque-forming unit.

In September 2019, an MVA vaccine, sold under the brand names Imvamune and JYNNEOS, was approved to prevent monkeypox and smallpox.98 The study by Rimoin et al.99 showed that the incidence of monkeypox cases was increased by 20-fold 30 years after discontinuation of vaccination against smallpox (0.72 vs. 14.42 per 10 000). It was also revealed that vaccinated individuals had a fivefold reduced risk for monkeypox than unvaccinated people (0.78 vs. 4.05 per 10 000).99

In the 2003 US outbreak, studies using investigational methods detected three unreported monkeypox cases in individuals who were given the vaccinia virus vaccine 13, 29, and 48 years before the monkeypox exposure. These cases were asymptomatic and unaware of their infection, showing that smallpox vaccination causes cross-protective immune responses against West African monkeypox.100

On August 9, 2022, the FDA issued an emergency use authorization for JYNNEOS to be administered intradermally for individuals older than 18 or subcutaneously for those younger than 18 considered to be at high risk for monkeypox infection.

Postexposure vaccination with the MVA vaccine might be recommended for patients who contact the patient or patient's materials without personal protection equipment.101 On the basis of CDC recommendation, the vaccine can prevent the onset of the disease if administered within 4 days of exposure. Vaccination between Days 4 and 14 might decrease the severity of the disease but might not exert preventive effects.102

In 2007, the US FDA approved a live replication-competent smallpox vaccine, ACAM-2000, for smallpox prevention in individuals at high risk for smallpox infection. Recently, ACAM2000 was made available for use against monkeypox under an Expanded Access Investigational New Drug application.103 However, it should be noted that it is not approved or authorized for emergency use against monkeypox.

ACAM2000 is administered at a single dose, and concern should be made regarding its shedding from the vaccination site and transmission potential to other people, particularly immunosuppressed patients who have close contact with vaccines. Also, reports of myocarditis, pericarditis, and serious vaccinia reactions make ACAM2000 to be substituted with MVA, which has a great safety profile.103, 104

6 LIMITATIONS

Because monkeypox has been around for a limited time, evidence-based classification of drugs' safety and efficacy is based on a few studies. Also, the diversity of animal models, which might affect the drug exposure, was not considered a confounding variable in categorizing the studies.

7 CONCLUSION

The outbreak of monkeypox in 2022 was initially identified in the United Kingdom, and the number of reported monkeypox cases is increasing. There are no approved treatments for monkeypox infections. However, the viruses belonging to the Orthopoxvirus genus are genetically similar. Hence, antivirals used to treat smallpox might be effective against monkeypox. Although EMA authorized the use of tecovirimat in monkeypox, there is a need for novel therapeutics with different mechanisms due to the risk of resistance.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Elnaz Khani: Investigation and writing – original draft. Bentelhoda Afsharirad: Writing – original draft. Taher Entezari-Maleki: Conceptualization; writing – review and editing, and supervision.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article since no new data were created or analyzed in this study.