Increased cases of influenza C virus in children and adults in Austria, 2022

Abstract

Sentinel surveillance of influenza-like illnesses revealed an increase in the cases of influenza C virus in children and adults in Austria, 2022, compared to previous years, following one season (2020/2021), wherein no influenza C virus was detected. Whole-genome sequencing revealed no obvious genetic basis for the increase. We propose that the reemergence is explained by waning immunity from lack of community exposure due to restrictions intended to limit severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 spread in prior seasons, pending further investigation.

1 BACKGROUND

Similar to other viruses in the family Orthomyxoviridae, influenza C virus (“ICV,” genus Gammainfluenzavirus) causes a respiratory infection in humans. Compared to influenza A and B viruses, less is known about ICV; however, it is thought to generally cause mild, flu-like symptoms, typically in young children. Serosurveys have suggested that exposure in humans is quite high, with nearly 90% of school-age children having been exposed to ICV.1, 2 Like influenza B virus, ICV is primarily an endemic human virus, although no major epidemics have ever been recorded apart from variable increased seasonal incidences.3-6 The incidence is likely underestimated as routine influenza diagnostic techniques (i.e., virus isolation) are not efficient, and molecular diagnosis is infrequently performed due to the low severity of infection.

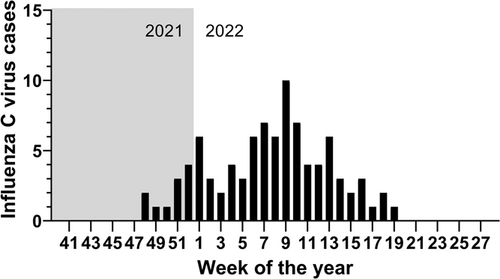

In Austria, annual sentinel surveillance of influenza-like illnesses is coordinated on a nationwide level. In addition to other respiratory viruses, molecular detection of ICV has been included in the diagnostic panel. This resulted in the detection of a few ICV infections per year (3 in 2016/2017, 8 in 2017/2018, 4 in 2018/2019, and 2 in 2019/2020). As previously reported, measures to prevent the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) drastically reduced the incidence of many respiratory viruses,7 and we noted that no cases of ICV were detected in the 2020/2021 season (Table 1). However, from January to March 2022, a total of 65 ICV cases were diagnosed from patients with influenza-like illness (ILI) via the Austrian influenza sentinel surveillance system (out of 2512 samples tested). At the time of writing (Week 28), a total of 91 cases of ICV were detected in 2022 (out of 4077 total samples), representing 2.2% of samples (Table 1). In our data set, only human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) showed a large increase in incidence similar to ICV in 2021/2022; however, the number/percentages of positives for all viruses except ICV were within the range of previous years (Table 1). The first case was detected in Week 48/2021, and the incidence peaked at 10 cases during Week 11 (Figure 1). The objective of this study was to describe the first cases of ICV and investigate whether viral genetics could explain the observed increase.

| Seasona | Total tested | IAV (%) | IBV (%) | ICV (%) | RSV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016/17 | 1120 | 486 (43.4) | 12 (1.1) | 3 (0.3) | 176 (15.7) |

| 2017/18 | 1952 | 350 (17.9) | 676 (34.6) | 8 (0.4) | 117 (6.0) |

| 2018/19 | 3278 | 543 (16.6) | 2 (0.1) | 4 (0.1) | 79 (2.4) |

| 2019/20 | 4950 | 805 (16.3) | 220 (4.4) | 2 (<0.1) | 66 (1.3) |

| 2020/21 | 7188 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (<0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 51 (0.7) |

| 2021/22b | 4077 | 248 (6.1) | 2 (<0.1) | 91 (2.2%) | 307 (7.5) |

- Abbreviations: IAV, influenza A virus; IBV, influenza B virus; ICV, influenza C virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

- a Season is defined as Week 40 of first year to Week 39 of the following year.

- b Season ends on Week 28 of 2022 (when this manuscript was prepared).

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sentinel samples are routinely screened for a panel of respiratory viruses, including rhinovirus and adenovirus, using previously described techniques for detecting viral nucleic acids.7 Specifically ICV was detected using a quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay with primers FluCNP+1068 and FluCNP−1161, and probe FluCNP1100 as previously described.8 Samples positive for SARS-CoV-2 were additionally screened by melting-curve-based assays to determine lineage (“VirSNiP”; TibMolBiol) or whole-genome sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq following the tiled amplicon approach of the ARTIC network (https://artic.network/ncov-2019) with library preparation and multiplexing using Nextera XT kit (Illumina).

Whole-genome sequencing of ICV was performed by targeted amplification with a one-step reverese transcription-PCR using conserved primers for the 5′ and 3′ ends of the genomic segments listed in Zhang et al.9 with additional primers (one forward and four reverse) covering variations of these conserved ends. The resulting amplicons were prepared for nanopore sequencing on a MinION R9.4.1 flow cell (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) with the ligation sequencing kit (SQK-LSK109) using the native barcoding expansion (EXP-NBD104). Reads were collected over 24 h with base calling in Guppy (v6.0.7). Data from fastq files were aligned to the C/Ann Arbor/1/1950 reference genome (NC_006306 – NC_006312), polished, and a consensus was extracted with the “medaka_consensus” pipeline (v.1.6.0). Consensus sequences (Supporting Information: Table S1) were aligned with previously published reference sequences using clustalw (Phyml, version Spring 2022).10 The reference sequences were selected as those for which all (or nearly all) genomic segments were available (Supporting Information: Table S2). Phylogenetic trees were estimated for seven open-reading frames (one per segment) over 1000 bootstrap replicates using SMS to select the optimal substitution models.11 Trees were drawn and annotated with “ggtree” and its dependencies.12

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

With the exception of 2020/2021, in which the majority of diagnosed cases from sentinel sampling were SARS-CoV-2 (not shown), total sampling was comparable to previous years (Table 1). We inferred that the increased incidence did not represent a sampling error (Table 1); however, we cannot exclude the possibility that patients with ILI were more likely to seek a diagnosis in the years after coronavirus disease 2019, potentially biasing the results. Although the majority (58%) were under the age of 7 (30% were under the age of 3), we recorded nine cases between the ages of 7–25, 14 between the ages of 26–40, and 11 between the ages of 41–60 years old (two age unknown). Notably, at least three adult cases (ages 24, 29, and 60) had comorbidities (Hashimoto myocarditis, asthma bronchitis, and diabetes mellitus with hypertension, respectively). As ICV is more often diagnosed in children, the observation that ~33% of ICV cases were adults provided further evidence that community transmission of ICV was increased (the age distribution in 2021/2022 was more similar to IAV, and not RSV as expected, in contrast to previous years; Supporting Information:Table 3). Furthermore, given that the sentinel program is comprised of patients with ILI, we inferred that this represented an increase in symptomatic disease resulting from ICV, perhaps suggesting a waning of humoral immunity to ICV in adults.

Among the ICV-positive cases, SARS-CoV-2 was additionally detected in 19 (21%) and variant screening determined that the genotypes switched from Omicron BA.1 (N = 7) to BA.2 (N = 11) after Week 9 (1 undetermined due to low viral load), a pattern that was confirmed by targeted whole-genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 on a subset of samples. Furthermore, we detected seven patients copositive for rhinovirus and four for adenovirus (one of which was identified as human adenovirus C serotype 2 by Sanger sequencing of the hexon gene region, the others were not characterized due to low viral load). The significance of copositivity among these viruses is unclear; we include the information for completeness, and detailed information on the number of samples with coinfection is provided in the Supporting Information: Material.

It is likely that the increased incidence was caused by a decreased prevalence in prior seasons due to Austria-wide government-mandated SARS-CoV-2 prevention measures. Fine-particle respiratory masks (FFP2) have been mandatory on public transport and in shops since March 2020, public gatherings have been restricted, and the requirements for proof of SARS-CoV-2 immune status in cafes, clubs, bars, and restaurants have likely limited indoor crowding and transmission events for SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory viruses. Nonetheless, we were interested in determining whether the increased incidence may be due to genetic changes in the circulating ICV strains (i.e., the emergence of novel reassortant strains or signs of significant drift variants). Therefore, we performed targeted whole-genome sequencing of 23 patient samples from 2022 with high viral load, as well as Austrian patient samples during prepandemic seasons: two from the 2017/2018 season and one from October 2019. Importantly, these represent the first published sequences of ICV from Austria.

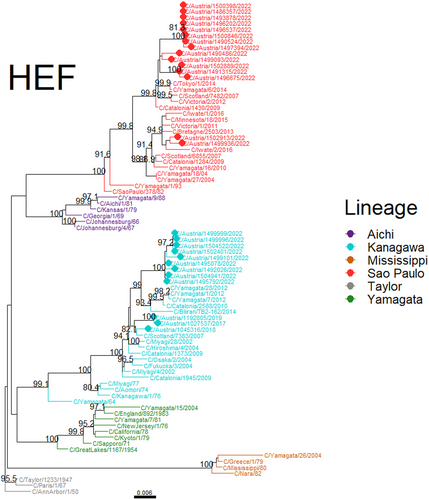

Based on the sequences of the hemagglutinin-esterase-fusion gene (HE), two lineages were present in 2022: Kanagawa and Sao Paulo (lineage names as defined by Matzusakai et al.)13 (Figure 2). While all three Austrian sequences from prior seasons were Kanagawa lineage HE, these two lineages were known to be circulating in Europe in recent years14 and are known to have been the predominant lineages circulating worldwide for many years.5, 15-17 Therefore, for example, the observed increase in cases is likely not due to the (re-)emergence of the Sao Paulo lineage in Austria in 2022. Within the Kanagawa lineage, sequences from 2022 had a Q165R substitution, while strains from the previous seasons had Q165. This site is part of the receptor-binding domain near an antigenic site.18 Other substitutions in or near the receptor binding domain were observed in the Sao Paulo lineage strains, including in the “190-loop” variable region (e.g., K190N) or adjacent (e.g., K195Q). Notably, two Sao Paulo-lineage strains contained the N190 and Q358, while all others had K190 and K358. We did not evaluate whether these led to major antigenic changes in the proteins; however, strains with these same substitutions in antigenic sites were documented in Europe and Asia before the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic18-20 (Figure 2). Phylogenetic analysis of the coding sequences of other major genes (nonstructural protein 1, matrix M1, nucleoprotein, and polymerase subunits PB1, PB2, and P3) showed a similar clustering of Austrian sequences with themselves and with published sequences from the last 5–10 years; however, no major reassortments were noticed (Supporting Information: Figures S1–S6 and Matzusakai et al.).13

4 CONCLUSIONS

We recorded an increased incidence of ICV in Austria in 2022 with a sentinel surveillance system. Whole-genome sequencing of the 2022 strains and prior (prepandemic) seasons showed that the circulating strains represented the two contemporary HE lineages that circulate worldwide. There was no indication that the surge in ICV during this season was necessarily due to antigenic drift or the emergence of genetically novel strains. Rather, it is possible that the increase in cases was due to waning humoral immunity following one or two seasons of reduced exposure and limited community transmission due to public health measures designed to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2. This conclusion was supported further by the observed incidence in adults with ILI; however, more investigations are needed, as a similar increase was not observed for other respiratory viruses.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study conception: Monika Redlberger-Fritz. Data collection: Monika Redlberger-Fritz and Jeremy V. Camp. Data analysis: Jeremy V. Camp. Data interpretation: Monika Redlberger-Fritz and Jeremy V. Camp. Microbiology analyses: Monika Redlberger-Fritz and Jeremy V. Camp. Drafting the manuscript: Jeremy V. Camp. Revising the manuscript: All authors. Approving the final version submitted: All authors. Study supervision: Monika Redlberger-Fritz.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Claudia Kellner and Christine Wukotitsch for their excellent technical assistance. This work was partly supported by MSD's Merck investigator Studies Program (MISP 61448).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical University of Vienna Protocol No. 1888/2021.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Anonymised database will be made available upon reasonable request. All sequences have been deposited in GISAID.