SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a inhibits cGAS-STING-mediated autophagy flux and antiviral function

Jiaming Su, Si Shen, Ying Hu contributed equally.

Abstract

Recognizing aberrant cytoplasmic dsDNA and stimulating cGAS-STING-mediated innate immunity is essential for the host defense against viruses. Recent studies have reported that SARS-CoV-2 infection, responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, triggers cGAS-STING activation. cGAS-STING activation can trigger IRF3-Type I interferon (IFN) and autophagy-mediated antiviral activity. Although viral evasion of STING-triggered IFN-mediated antiviral function has been well studied, studies concerning viral evasion of STING-triggered autophagy-mediated antiviral function are scarce. In the present study, we have discovered that SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a is a unique viral protein that can interact with STING and disrupt the STING-LC3 interaction, thus blocking cGAS-STING-induced autophagy but not IRF3-Type I IFN induction. This novel function of ORF3a, distinct from targeting autophagosome-lysosome fusion, is a selective inhibition of STING-triggered autophagy to facilitate viral replication. We have also found that activation of bat STING can induce autophagy and antiviral activity despite its defect in IFN induction. Furthermore, ORF3a from bat coronaviruses can block bat STING-triggered autophagy and antiviral function. Interestingly, the ability to inhibit STING-induced autophagy appears to be an acquired function of SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a, since SARS-CoV ORF3a lacks this function. Taken together, these discoveries identify ORF3a as a potential target for intervention against COVID-19.

1 INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has swept the world since 2019, causing an epic public health crisis and posing a tremendous economic burden.1, 2 To date, the rampant spread of SARS-CoV-2 has caused over 555 million infections and 6.3 million deaths worldwide.3 Thus, it is urgent that we clearly delineate the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 and identify efficient therapies to antagonize this potentially deadly virus.

The DNA pattern recognition receptor cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) is a key sensor for recognizing viral infection in the cytoplasm of cells.4 Recent studies have demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 infection disrupts mitochondrial homeostasis, inducing mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) release.5 It also causes syncytia formation, which leads to the shuttling of chromatin and micronuclei from the nucleus to the cytoplasm.6, 7 This aberrant cytoplasmic DNA is sensed by cGAS, activating cGAS-STING-mediated antiviral responses. To date, cGAS-STING-mediated, IRF3-Type I-interferon (IFN)-dependent antiviral defenses and the counteracting responses by diverse viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, have been widely reported.4, 8 Apparently, STING-mediated Type I IFN is dampened in bats, which are often commensal with multiple viruses, including coronaviruses.9 Bat coronaviruses (CoVs) are highly conserved when compared to SARS-CoV-2 and are believed to be the most likely origin of SARS-CoV-2.10 These observations have led us to speculate that the Type I IFN-independent function of STING may play an important role in antiviral responses.

Autophagy is a fundamental and highly conserved intracellular degradation process in eukaryotes for eliminating damaged organelles, protein aggregates, and invading pathogens.11 cGAS-STING-induced autophagy is a primordial Type I IFN-independent activity that can significantly inhibit the replication of viruses,12 but little is known about how viruses thwart this cGAS-STING-triggered autophagy. We now propose that to facilitate its survival, SARS-CoV-2 may have evolved evasion strategies to suppress autophagy.

In the present study, by screening reported STING suppressors and SARS-CoV-2-encoded proteins, we have identified ORF3a as a potent inhibitor of STING-mediated autophagy that facilitates viral replication. In addition, we have found that bat-CoV ORF3a can antagonize bat STING-triggered autophagy, and this suppression can be neutralized by a small molecule inhibitor, TPEN. Notably, among human coronaviruses, only SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 encode ORF3a. We found that, as compared to SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV ORF3a is less effective in defending against STING-mediated autophagy, which may explain the epidemic potential of SARS-CoV-2. Taken together, our results indicate the unique role of the SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a in suppressing STING-mediated autophagy, which benefits viral replication and also provides potential targets for the development of therapeutic strategies against SARS-CoV-2.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Viruses and cell lines

HEK293T cells (ATCC, CRL-3216) and HeLa cells (ATCC, CCL-2) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin solution. EV-A71 and HSV-1 GFP were prepared as previously described.13

2.2 Plasmids, antibodies and reagents

mCherry-GFP-LC3 (#22418) and mCherry-LC3 (#40827) were purchased from Addgene. Nematostella vectensis, Myotis davidii, Rhinolophus sinicus, Mus musculus, Gallus gallus, Xenopus tropicalis, and Danio rerio STING-Flag; HPV E7-HA (NC_001357.1), Adenovirus E1A-HA (NC_001405.1), KHSV vIRF1-HA (NC_009333.1), HCV NS4B-HA (YP_009709868.1), HCMV UL82-HA (P06726.2), YFC NS4B-HA (NP_776008.1), DENV NS2B3-HA (P14340.2), ZC45 ORF3a-HA (MG772933.1), RaTG ORF3a-HA (QHR63301.1), and ORF3a chimeras were obtained from Generay Biotech Co., Ltd, CN, and cloned into VR1012. All the coronavirus protein constructs, Homo sapiens STING wild type and truncation plasmids, Myc-cGAS, IFNα, and NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmids and Vpx-HA have been described previously.14, 15 Plasmids were verified by sequencing before transfection using the Hieff TransTM Liposomal Transfection Reagent (YeasenBiotech, CN) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The following antibodies were used for western blot analysis or immunofluorescence: anti-Flag (Sigma, F3165), anti-Myc (Millipore, 05-724), anti-p62 (MBL, PM045), anti-LC3B (Sigma, L7543), anti-GAPDH (Proteintech, 60004-1-Ig), anti-HA (Invitrogen, 71-5500), anti-Histone (Genscript, A01502), anti-IFIT3 (Proteintech, 15201-1-AP), anti-IRF3-p (Cell Signal, 4974), GM130 (abcam, ab52649), DAPI (Sigma, 28718-90-3), bafilomycin A1 (MCE, HY-100558), anti-Flag M2 Affinity Gel (Sigma, A2220), Alexa Fluor 488 AffiniPure Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) (Yeasen, 33106ES60). and Alexa Fluor 647 AffiniPure Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) (Yeasen, 33113ES60). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-mouse or anti-rabbit) were purchased from HuaBio.

2.3 Virus infection and quantitation

HEK293T cells were transfected with indicated plasmids and then infected with HSV-1 GFP and EV-A71. At 24 h postinfection, the cells were washed with cold PBS, and HSV-1 GFP was measured by flow cytometry according to the manufacturer's instructions. EV-A71-infected cells were observed for morphological changes and photographed by light microscopy at 100× magnification. The viral RNA levels of EV-A71 were evaluated by real-time PCR using SYBR Green. EV-A71-VP1 primers: Forward, 5′- CAAGGGATGGTACTGGAAGT-3′; Reverse, 5′-GATCGGTAGAGGTAGTGGAA-3′.

2.4 Dual-luciferase assays

HEK293T cells were transfected with 100 ng of the Firefly luciferase reporter plasmids for the IFNα promoter and NF-κB response element; 5 ng of Renilla luciferase control plasmid (pRL-TK); and the indicated amounts of the expression plasmids per well. Dual-luciferase activity was measured as previously described.14

2.5 Confocal microscopy

HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids, with or without bafilomycin-A1. Images were captured as previously described.14

2.6 Flow cytometry

After HSV-1 GFP infection, cells were washed with cold PBS and analyzed on a DxFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). Apoptosis was evaluated using an Annexin V-APC/7AAD apoptosis kit (Multi Sciences Biotech, CN). A DxFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) was used to quantify apoptosis detection, and all the data analysis was performed using FlowJo software.

2.7 Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

HEK293T cells were seeded into 6-cm dishes and transfected with the indicated plasmids using Hieff TransTM Liposomal Transfection Reagent (YeasenBiotech), with or without bafilomycin-A1. Immunoblotting and co-immunoprecipitation were performed as previously described.14

2.8 Immunoblot band quantitation

Quantification of band intensities was performed using ImageJ (version 1.50i).

2.9 Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software. All data are shown as means ± SD. The statistical significance analyses were performed using a two-sided unpaired t-test (p values) with exact values.

3 RESULTS

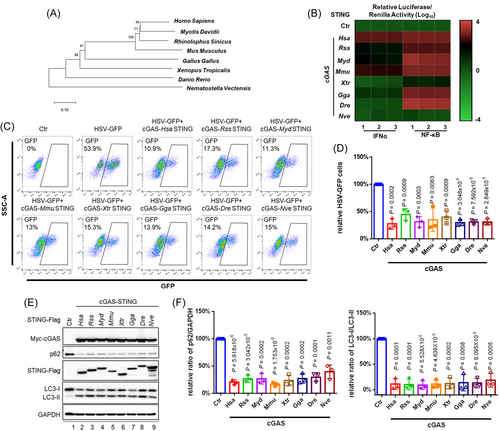

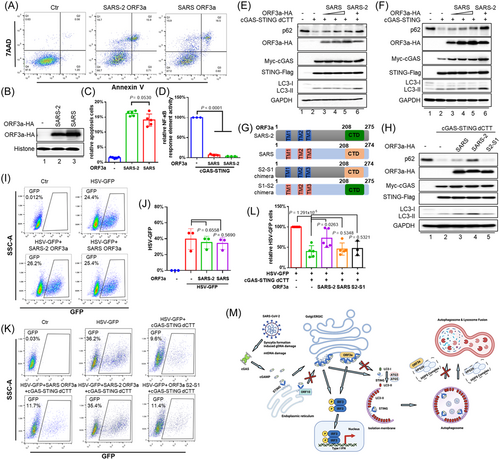

To investigate the involvement of the cGAS-STING signaling pathway across phylogenetic kingdoms in innate immune activation and antiviral defense, we employed diverse STING molecules from Homo sapiens to Nematostella vectensis (Figure 1A). Using established experimental systems for the detection of cGAS-STING-triggered innate immune activation, we discovered that different STING molecules exhibited different activity in terms of stimulating downstream IFNα and NF-κB responses (Figure 1B). For these experiments, the replication of herpes simplex virus (HSV) was evaluated in HEK293T cells. As compared to Homo sapiens STING (HsaSTING), STING in the bats Rhinolophus sinicus and Myotis davidii (RssSTING and MydSTING) was defective in the induction of Type I IFN, as has been previously reported9; however, these STING molecules restricted HSV-1 replication efficiently, indicating the presence of a cGAS-STING-signaling antiviral defense acting in a Type I IFN-independent fashion (Figure 1C,D). In addition, STING from Xenopus tropicalis and Nematostella vectensis (XtrSTING and NveSTING), which barely induced activation of the NF-κB response element, also showed a significant inhibition of HSV-1 replication, suggesting that the cGAS-STING antiviral defense is independent of NF-κB induction. A unique and important feature of the cGAS–STING pathway is the robust activation of autophagy in addition to the induction of interferons and NF-κB responses.12 We observed that overexpression of cGAS-STING induced the activation of autophagic flux, as monitored by p62 degradation and LC3 lipidation (Figure 1E,F). Notably, STING from all the various species examined was capable of triggering autophagy induction (Figure 1E,F) and efficiently restricted HSV-1 replication (Figure 1C,D). Thus, the cGAS-STING-triggered antiviral defense appeared to be independent of IFN and NF-κB signaling. Moreover, the induction-related autophagy of cGAS-STING appeared to be an evolutionarily conserved activity that played a dominant role in antagonizing viral replication.

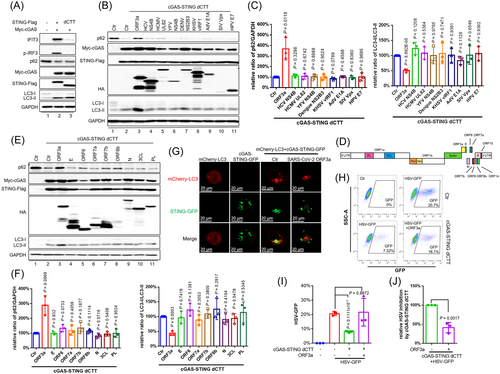

All viruses have developed efficient evasion mechanisms to survive. In previous studies we have demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 proteins are capable of a unique and complementary suppression of cGAS-STING and RNA sensing-triggered innate immune responses.14 Since cGAS-STING-triggered autophagy is prominent in antiviral replication,12 we conducted screening to determine whether any viral proteins could potentially target the STING-autophagy axis. For this purpose, we synthesized viral proteins from RNA viruses (SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a, HCV NS4B, DENV NS2B3, and YFV NS4B), DNA viruses (HPV E7, HCMV UL82, AdV E1A, and KHSV vIRF1), and retrovirus (HIV-2/SIV Vpx) that have been reported to associate with STING and subsequently disrupt STING's downstream signalosome assembly. To further exclude the effect of STING-mediated interferon activity against DNA viruses, we generated a construct with a STING C-terminal tail truncation (STING dCTT) that is defective in the stimulation of Type I IFN and Type I IFN-stimulated gene expression15 but functional in terms of autophagy induction12 (Figure 2A). Surprisingly, the SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a could be distinguished from various other viral proteins in terms of impeding cGAS-STING-mediated p62 degradation, as shown in Figure 2B,C. It has been reported that SARS-CoV-2 3CL can also inhibit cGAS-STING signaling.14 Therefore, we asked whether other SARS-CoV-2 structural and accessory proteins (Figure 2D) might be involved in STING-based suppression of autophagy induction. For this purpose, we co-expressed cGAS-STING dCTT with each individual SARS-CoV-2 viral protein in HEK293T cells and discovered that only ORF3a significantly restored p62 expression (Figure 2E,F). We observed an interaction of ORF3a with STING as well as STING dCTT, both of which are competent to induce autophagy (Supporting Information: Figure S1a and Figure 2A). Moreover, we detected intracellular co-localization of STING and ORF3a (Supporting Information: Figure S1b). STING activation induces co-localization of STING and LC3 which is important for STING-triggered autophagy.16 We discovered that ORF3a inhibited the co-localization of STING and LC3 (Figure 2G). Consistent with this observation, we also discovered that ORF3a inhibited the interaction between STING and LC3-II (Supporting Information: Figure S2a).

Furthermore, ORF3a efficiently restored the replication of HSV-1 (Figure 2H–J) and EV-A71 (Supporting Information: Figure S3a,b), which had been repressed in the presence of cGAS-STING dCTT. We have previously demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a selectively inhibits cGAS-STING-NF-κB signaling, but not the RIG-I-like Receptor (RLR) pathway,14 implying that the cGAS-STING pathway is a crucial barrier during SARS-CoV-2 infection and that SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a is a potent inhibitor of cGAS-STING. In addition, the SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a has a Cys-rich region with the potential to bind zinc. Interestingly, we found that N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis (2-pyridylmethyl)-ethylenediamine (TPEN), a lipid-soluble zinc metal chelator, was able to block ORF3a function (Supporting Information: Figure S2b). Taken together, these data indicate that, among diverse viral proteins, SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a is a unique and potent inhibitor of the STING-autophagy axis that facilitates efficient viral replication and helps viral pathogenesis.

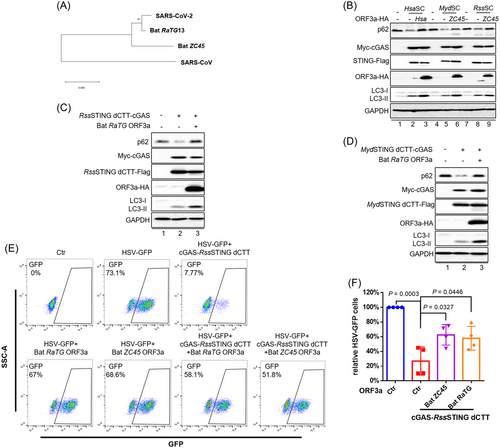

Bats serve as reservoirs for many viruses, including coronaviruses.9 STING molecules in all the bats examined to date have proved defective for the induction of Type I IFN and have compromised antiviral activity. We have now demonstrated that STING from the bats Rhinolophus sinicus (RssSTING) and Myotis davidii (MydSTING)9 can induce autophagy (Figure 1E,F). Interestingly, though, diverse ORF3a molecules encoded by bat coronaviruses (Figure 3A) have evolved an evolutionarily conserved suppression of bat STING dCTT-triggered autophagy (Figure 3B–D). Functionally, bat ORF3as, including RaTG and ZC45, were effective in rescuing HSV-1 suppression induced by RssSTING dCTT-mediated autophagy induction (Figure 3E,F).

Since, ORF3a is only encoded by SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 among human coronaviruses, and this ORF is conserved in terms of the induction of apoptosis (Figure 4A–C) and antagonism of cGAS-STING-mediated NF-κB activity (Figure 4D), we wondered whether SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a would both be able to suppress STING-mediated autophagy. Surprisingly, we discovered that the ORF3a derived from SARS-CoV was less capable of inhibiting STING-triggered p62 degradation (Figure 4E,F), and autolysosome formation (Supporting Information: Figure S4a,b) than was SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a. To pursue this question further, we constructed an ORF3a S2-S1 chimera that consisted of the N-terminus of SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a and the C-terminus of SARS-CoV ORF3a, and this chimera showed a loss of function (Figure 4G,H). Interestingly, the ORF3a S1-S2 chimera, unlike SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a,17, 18 lost the ability to inhibit the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes (Figure 4G and Supporting Information: Figure S4c,d) but maintained the ability to inhibit STING-triggered autophagy (Supporting Information: Figure S4e,f). Consistently, SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a and the S1-S2 chimera showed stronger neutralization of cGAS-STING dCTT autophagy-mediated HSV-1 inhibition than did SARS-CoV ORF3a or the chimeric ORF3a S2-S1 (Figure 4I–L and Supporting Information: Figure S4g,h). This unusual effect of the SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a may have contributed to some of the unique biological properties of the SARS-CoV-2.

4 DISCUSSION

Evasion of host innate immunity is essential for the survival of viruses. We have shown that SARS-CoV-2 infection triggers cGAS-STING activation, which leads to the generation of Type I IFN and autophagy-mediated antiviral activity. The means by which viruses evade cGAS-STING-triggered, autophagy-mediated antiviral activity is poorly understood.19 ORF3a is a virion-associated protein,20 and thus it plays an important role in the early stage of SARS-CoV-2 infection. We observed here that SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a was able to block cGAS-STING-induced autophagy and its antiviral activity (Figure 2B–J). Surprisingly, SARS-CoV ORF3a had an impaired ability to block cGAS-STING-induced autophagy and the resulting antiviral activity (Figure 4E–L), although ORF3a from both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 maintained the ability to induce apoptosis (Figure 4A–C)21 and NF-κB inhibition (Figure 4D).14

SARS-CoV-2 ORF10 has also been reported to inhibit cGAS-STING-induced autophagy.8 Unlike ORF10, which also affects STING foci formation and IRF3 activation, ORF3a specifically affects cGAS-STING-induced autophagy, without affecting STING foci formation or IRF3 activation (Figure 4M).

Bat STING is defective in stimulating IRF3-Type I IFN activation (Figure 1B)9; however, we have now discovered that bat STING activation can still induce autophagy and antiviral activity (Figure 1C–F). On the other hand, ORF3a from bat coronavirus has the ability to suppress bat STING-triggered autophagy and its antiviral function (Figure 3B–F), even though STING-mediated autophagy is a primordial, conserved antiviral activity.12 The ability to inhibit STING-induced autophagy appears to be an acquired attribute of SARS-CoV-2 and bat coronavirus ORF3a, and this inhibition is sensitive to a small-molecule inhibitor, namely TPEN (Supporting Information: Figure S2b). Thus, our study identifies ORF3a as a potential drug target for intervention against COVID-19.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jiaming Su, Si Shen, and Ying Hu carried out most of the biochemical experiments, with help from Yanpu Wang, Shiqi Chen, and Leyi Cheng. Yanpu Wang conducted the immunostaining and confocal microscopy experiments. Yong Cai and Wei Wei contributed the key reagents. Jiaming Su, Si Shen, and Yajuan Rui performed the viral infection experiments and plasmid construction. Xiao-Fang Yu, Yajuan Rui, and Yanpu Wang contributed to the supervision and data analysis. Xiao-Fang Yu directed the project, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper, with help from all of the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (numbers 82102384, 82172239, 92169203, 31900133, 31970151, 32041006), National Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LY22C080002, LQ21C010001), and Leading Innovative and Entrepreneur Team Introduction Program of Zhejiang (2019R01007). We thank Q. Dong for helping with the confocal microscopy analysis and N. Zhao, Y. Huang, and Q. Lv for providing technical assistance.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data, materials, and methods are included in the article.