Coverage of Japanese encephalitis routine vaccination among children in central India

Abstract

We aimed to estimate the coverage of Japanese encephalitis (JE) vaccination in central India to help explain the continued occurrence of JE disease despite routine vaccination. We implemented a 30-cluster survey for estimating the coverage of JE vaccination in the medium-endemic areas implemented with JE vaccination in central India. The parents were enquired about the uptake of the JE vaccine by their children aged 2−6 years, followed by verification of the immunization cards at home along with reasons for non-vaccination. Vaccination coverage was reported as a percentage with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We estimated high coverage of live-attenuated SA 14-14-2 JE vaccination in Maharashtra (94.8%, 95% CI: 92.7−96.3) and Telangana (92.8%, 95% CI: 90.0−94.9). The vaccination card retention was 90.3% in Maharashtra and 70.4% in Telangana state. There were no gender differences in coverage in both states. A similar level of JE vaccination coverage was observed during the year 2013−2021 in both states. In Maharashtra, the maximum age-wise coverage was 96.6% in the >60 months age category, whereas in Telangana it was in the <24 months age category (97.2%). The timeliness of JE vaccination was appropriate and similar in both states. We found a very good agreement between JE and measles-rubella vaccinations administered simultaneously. The reasons for non-vaccination were the shortage of vaccines and the parental migration for work. The coverage of JE vaccination was high in medium-endemic regions in central India. Vaccination effectiveness studies may help further explain the continued incidence of JE.

1 INTRODUCTION

Japanese encephalitis (JE) is mostly a childhood disease. South, Southeast, and East Asia residents are at higher risk, along with visitors to the JE endemic areas. The fatality is 20%−30% and over 30%−50% of the JE recovered individuals have persisting sequelae, mostly neuropsychiatric.1, 2 The disease inflicts a significant socioeconomic and public health burden. Treatment is mostly supportive and symptomatic.3

The areas endemic to JE are recommended to implement the JE vaccine in national immunization programs even if JE cases are low.4 As animal reservoirs involve multiple hosts, the elimination of the JE virus is very difficult. Therefore, vaccination is considered an effective preventive measure. The efficacy of the live-attenuated SA 14-14-2 JE vaccine is reported between 80% and 99% following partial vaccination and over 98% with complete vaccination. However, the incidence of JE continues despite vaccination in supplemental campaigns and routine immunization schedules.5, 6

The JE among children is a major public health problem in central India.6, 7 After 2006, JE endemic districts were prioritized for the implementation of JE vaccination in Maharashtra and Telangana states. Initially, JE vaccination was introduced in campaign mode using a single dose among 1−15 years children along with recommended surveillance standards.7, 8 The routine immunization schedule, for the protection of susceptible birth cohorts, includes two doses of live-attenuated SA 14-14-2 JE vaccine—first at 9−12 and second at 16−24 months.9 Since October 2013, the JE endemic areas have implemented a two-dose schedule, administered with the measles-rubella (MR) vaccine.

Acute encephalitis syndrome (AES) cases are reported year-round from endemic districts of Maharashtra and Telangana states. An increase in JE cases despite JE vaccination raises concerns regarding the adequacy of JE vaccination uptake in medium-endemic central India. Therefore, in an attempt to explain the reasons for the continued occurrence of JE and AES in central India, we aimed to estimate JE vaccination coverage, as one of the most important factors, achieved in routine immunization schedules in Maharashtra and Telangana states in central India.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

We designed a 30-cluster survey for estimating the uptake of JE vaccination in routine immunization schedules in endemic districts.

2.2 Setting

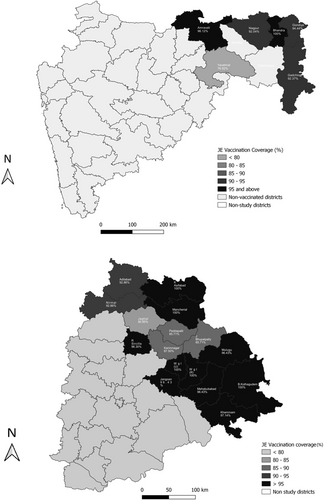

The coverage survey was undertaken in districts that implemented vaccination against JE in a routine immunization schedule by trained field teams. The JE-vaccinated districts of Maharashtra (six districts) and Telangana 16 districts) were considered (Figure 1). The survey was undertaken from October to December 2020. The Institutional Ethics Committees at ICMR-National Institute of Virology Pune, Government Medical College Nagpur, Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences at Sewagram, and Kakatiya Medical College Warangal (Telangana) approved the study protocol. We obtained written informed consent from parents or guardians before the interview.

2.3 Participants

The children having the opportunity of vaccination with two doses of JE were selected in surveyed districts in both states for interviewing with their parents or guardians.

2.4 Study size and procedures

The localities in each district were selected using the probability proportional to size sampling.2 The sample size was estimated considering vaccination coverage of 50% and absolute precision of 5% with a design effect of 2, as an assumption of 50% coverage provided the highest sample size. This was considered for comparisons between rural-urban and age.

In Maharashtra, six JE-vaccinated districts associated with the two study sites were surveyed. The survey was conducted from October 23, 2020 to December 24, 2020. A total of 630 children were surveyed. From every district, 15 clusters were selected with 7 children from each cluster, thus 105 children were surveyed from each district, making 630 children from six districts. In Telangana state, the survey was conducted in 16 districts in Northern Telangana from November 17, 2020 to December 30, 2020. A total of 445 children were surveyed including 7 children from each cluster with every district having 4 clusters. Overall, 1075 children were surveyed from both states. The survey districts with clusters of localities surveyed are presented as a study area map (Figure 1).

2.5 JE vaccination coverage survey

Before the actual start of the survey, the questionnaire was tested during the pilot survey while visiting the AES cases. The survey was designed and undertaken using the WHO vaccination coverage survey manual.2 The survey data were collected using the structured pretested vaccination coverage questionnaire using tablet-based data collection and entry on the Epi-Info software tool. The survey was done through house-to-house visits. In every selected cluster, a random starting point was identified before the start of the survey. Households were visited and enquired about the presence of an eligible child. Only 1 child was randomly selected per household having more than one eligible child. The next adjacent household was visited if the selected household did not have any eligible children. This procedure was continued till 7 children from each selected cluster were surveyed. The child was considered fully JE vaccinated if two doses of live-attenuated SA 14-14-2 JE vaccine were received at 9-12 months and 16−24 months.

During the survey, parents or guardians (most preferable mothers) of the child were interviewed and information was entered into the tablet application. The JE vaccination status of each child was enquired from the parent or guardian by memory recall. The JE vaccination doses were confirmed by requesting the parents to show the vaccination card. The local health centers were visited for the verification of vaccination records. We sought the help of an auxiliary nurse midwife or accredited social health activist. The reasons for non-vaccination were also recorded. The information related to eco-epidemiology like the presence of pigs in the neighborhood, water bodies, birds, and paddy fields were also obtained along with mosquito bite prevention methods. After completing the survey, parents were educated on JE risk, transmission, and control measures.

2.6 Statistical analysis

We managed data using MS Excel and Epi-Info software (Version 7.2.4). The proportions were considered for summarizing the characteristics of the study participants. The percentages were reported with 95% confidence intervals and comparisons using standard error of the difference between two proportions. A p < 0.05 was considered significant.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographic characteristics

We surveyed 90 clusters in eastern Maharashtra and 64 clusters in northern Telangana (Figure 1). In Maharashtra, 75.6% of participants were from rural areas as against 24.4% from urban. There were 45.7% boys. The 24−59 months of age contributed to 66.8% of the surveyed children. In Telangana state, 70.1% were rural participants as against 29.9% urban. There were 55.1% boys. There were 62.3% of children from the 24−59 months age category. Study participant representation was similar in Maharashtra and Telangana States, except for gender distribution. Girls were more represented in Maharashtra, whereas boys were more in Telangana State.

In both Maharashtra and Telangana States, mostly mothers were the respondents (91.0% and 97.5%, respectively). Overall, only 3.9% of mothers from Maharashtra and 9.5% of mothers from Telangana had no formal education. In Maharashtra, 90.3% of parents had the vaccination card of their child available with them, whereas in Telangana it was 70.4%.

The presence of pig, water birds, and paddy fields was reported by 6.8%, 1.4%, and 26.1% of households, respectively in Maharashtra, whereas it was 26.2%, 23.8%, and 29.3% in Telangana. In Maharashtra, the majority of people were using mosquito coils (70.5%) followed by the use of mosquito net (36.8%), fully covered clothing (23.5%), application of mosquito repellent creams applied to the skin (16.3%), and window or door screen user (6.7%). In the Telangana state also, mosquito coils (49.4%) were used commonly followed by the use of mosquito net (17.1%), fully covered clothing (8.6%), application of mosquito repellent creams to the skin (4.0%), and window or door screen (3.3%).

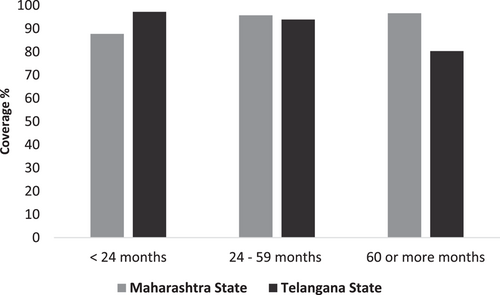

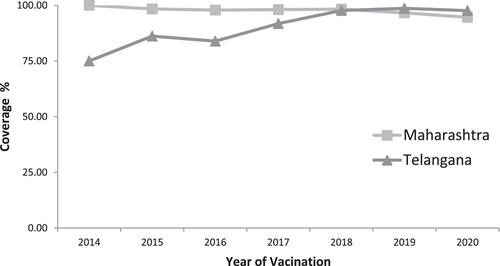

3.2 JE vaccination coverage

The coverage of full immunization that is, receiving both doses of the live-attenuated SA 14-14-2 JE vaccine was above 90% in both states (Figure 2). The vaccinated children were cross-checked and verified through vaccination cards possessed by parents in 83.4% of cases and the rest through records kept at the public health facilities. In Maharashtra state, among 630 children surveyed, 597 (94.8%) were vaccinated. In Telangana state, among 445 children surveyed, 413 (92.8%) received both doses of the JE vaccine. The age-wise comparisons of coverage between Maharashtra and Telangana had a significant difference (p < 0.001). Age-wise percentage coverage significantly increased with an increase in age in Maharashtra state. However, it significantly decreased with an increase in age in Telangana state (Figure 3). The year-wise vaccination coverage was comparable in Maharashtra and Telangana states. However, in Maharashtra, the overall JE vaccination coverage was higher than in Telangana state from 2014 to 2017 (Figure 4). All comparisons of vaccination coverage between Maharashtra and Telangana states were statistically nonsignificant. There were no significant differences noted in urban-rural and boys−girls comparisons (Table 1).

| Vaccination coverage | Maharashtra | Telangana |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 94.8 (92.7−96.3) | 92.8 (90.0−94.9) |

| Area-specific | ||

| Urban | 97.4 (93.5−98.9) | 93.9 (88.4−96.8) |

| Rural | 94.3 (91.8−98.0) | 94.3 (91.1−96.3) |

| Gender-specific | ||

| Boys | 94.1 (90.7−96.2) | 94.3 (90.6−96.5) |

| Girls | 95.3 (92.5−97.1) | 94.0 (89.8−96.5) |

| Age-specific | ||

| <24 months | 87.7 (79.4−93.0) | 97.2 (92.0−99.0) |

| 24−59 months | 95.7 (93.3−97.2) | 93.9 (90.3−96.1) |

| 60 months or morea | 96.6 (91.6−98.6) | 80.3 (68.6−88.3) |

- Note: The numbers presented above are percentages along with 95% CIs in brackets.

- Abbreviation: CI, confidence intervals.

- a The difference between states was significant.

3.3 Timeliness and reasons for incomplete and delay in JE vaccination

The timeliness of live-attenuated SA 14-14-2 JE vaccination in Maharashtra was 89.2% and 88.9% in Telangana. In Maharashtra, the reasons for incomplete vaccination were the nonavailability of vaccines at the vaccination center (50.0%) followed by migration (25.0%). In Telangana, the nonavailability of vaccines at vaccination centers (42.4%) was followed by migration (44.1%).

3.4 JE-MR vaccination concordance

We observed good concordance between JE and MR vaccinations. The JE-MR vaccination concordance was above 95% in both the Maharashtra and Telangana states. A positive agreement was also observed among both the doses of the JE and MR vaccines.

In summary, the JE vaccination coverage was high in both Maharashtra and Telangana. The timeliness and year-wise JE vaccination coverage were appropriate. A high concordance was observed between JE and MR vaccination. Parents' awareness was highly reflected by high uptake and good retention of vaccination cards, 90.3% in Maharashtra and 70.4% in Telangana.

4 DISCUSSION

The vaccination coverage studies are very important for assessing the local performance of vaccination programs.9 The JE endemic districts in Maharashtra and Telangana states report the incidence of JE and AES cases despite the implementation of the routine JE vaccination.6, 10 Therefore, we implemented a vaccination coverage survey to understand the level of uptake of JE vaccination and thus guide local health decisions on prioritization of prevention and control measures.

In summary, we found high JE vaccination coverage of above 90% in both states. In Maharashtra, the coverage and timeliness of both doses of JE vaccination in the routine schedule were slightly higher than in Telangana state. Most parents had retained the vaccination cards for their children indicating high awareness of parents. In Maharashtra state, coverage increased with an increase in the age of children. However, it was the opposite in Telangana state. The reasons for non-vaccination or delayed vaccination included the nonavailability of JE vaccine doses, the access of parents to the health centers, and their migration for work or employment. The timeliness of JE vaccination is acceptable. The additional risk factors like pigs, water birds, and paddy fields were higher in Telangana. The year-wise coverage had a similar pattern in Maharashtra and Telangana. We noticed good concordance between the JE and MR vaccine. This indicates favorable attitudes toward JE and other vaccinations. However, earlier studies in endemic areas in India have identified missed opportunities for vaccination uptake although vaccine effectiveness was acceptable.11, 12

We selected the children who had an opportunity for receiving two doses of the JE vaccine. This allowed us for additional data collection for understanding coverage over the last 5 years period. Random selection of 7 children was done irrespective of the vaccination status of the child.2 We could verify the vaccination details from the vaccination card provided by parents in most children and additional records maintained by healthcare workers. Studies reported earlier could hardly verify the vaccine doses using the vaccination cards, as they were not available to estimate vaccination coverage in India11, 12; with only half of the guardians having vaccination cards with them outside India.13

A few JE cases were reported among adults from the study areas earlier indicating the shift of JE and AES cases from children to adult age groups.10 Some study groups have also noticed a similar shift from children to adult populations in other areas in India.14-17 The JE vaccination in adults is not implemented in our study areas to date. However, a special campaign for JE vaccination in adults (>15 years) was implemented in Assam earlier.18 There is a need to monitor coverage among children along with the incidence of JE among endemic areas for assessing the need for changes in JE vaccination strategies in medium-endemic central India.

Studies have shown that the JE vaccine in routine immunization results in a decrease in JE cases.19-24 The susceptible individuals will be prone to the risk of disease even though lower numbers of JE cases are observed after the implementation of JE vaccination programs. The neglected areas of medium-endemic central India have different seasonality.25 Therefore, there is a need for further investigations, surveillance studies, follow-up, and management of JE cases as per the national guidelines for surveillance of AES recommended in sentinel sites supported with diagnostic testing.8 These studies would help in assessing the impacts of JE vaccination.

Confidence in vaccines and vaccination programs is very essential.26 There are no such studies conducted on JE vaccination coverage and effectiveness in medium endemic areas in central India, although such studies are reported from epidemic and high-endemic regions in India.12 If JE and AES cases continue to be reported despite high vaccination coverage, the effectiveness of vaccination may be considered for explaining the continued occurrence of JE and AES along with operational research aspects of vaccination programs.9, 11, 12

In a study from the eastern part of India, 3 of the 4 children got at least one dose of the JE vaccine in the Gorakhpur division of Uttar Pradesh.11 The coverage in 2015 had improved significantly over the period of 2 years.12 The second dose coverage was low, with only 60% of children receiving the second dose of the JE vaccine. In a study in 2010 in Karnataka state, coverage was 92% in children as against the reported 83.85% in Mandya district; it was only 70.0% in Koppal, similar to the reported coverage of 69.8%.27 JE vaccination coverage was high (93.0%) in Myanmar in 2018.28 Our findings are similar to the study in the Yangon Region, Myanmar in 2019 which reported a high level (97.2%) of JE vaccination coverage.13 The high coverage is achievable with committed ground-level healthcare workers, despite the deficits in knowledge and perception about JE and AES indicating trust in the healthcare system.13 The program implementation monitoring may consider the coverage surveys.

As our study had very high JE vaccine coverage, the effectiveness of the existing and widely used live-attenuated SA 14-14-2 JE vaccine needs to be considered further. The effectiveness of the JE vaccine used in India is not available in JE medium-endemic regions although over 70% effectiveness is reported in high-endemic areas.25 In India, low seroconversion rates have been documented post the live attenuated SA-14-14-2 vaccine, ranging from 58% to 74%, but the clinical significance remains unknown. Additionally, the dengue virus has been hypothesized to interfere with the immunogenicity of the SA-14-14-2 vaccine.29 Emerging genotypes could also make the currently licensed vaccines, which are all genotype III JEV, ineffective; thus, there is a need to monitor predominantly circulating JEV genotypes.26, 29 There could also be a waning of neutralizing antibodies after the live attenuated vaccines, and this needs to be investigated further.30 However, the recent paper presents evidence in support of evidence of cross-protection, although slightly lower than for the same genotype, offered against other genotypes in an experimental model using swine.31 This finding provides reassurance on the protection and effectiveness of existing genotype III JE vaccines, although this needs to be monitored for the effectiveness of current vaccines in humans in future.

We have a limitation of not reporting JE vaccination effectiveness study findings in this manuscript as it is being reported separately. Although the contribution of JE in AES cases has been reported to be around 10% in most JE high-endemic regions in the north and northeast India, the contribution of JE in medium-endemic regions in central India is slightly higher in our earlier reported studies among children6 and also in all age groups,10 as compared to the north and northeast India regions which experience seasonal outbreaks during postvaccination period. Also, there is a likelihood of some AES cases to be associated with JE, although not confirmed with available testing efforts, thereby having an expected decrease in AES cases. However, AES cases continued to be reported in central India regions signifying the possibility of non-JE causes.

There may be various issues including inadequate vaccine doses as indicated by parents. Thus, operational aspects including the availability of adequate doses and social reasons need to be considered. We had a limitation in implementing the JE vaccination coverage survey with a larger number of participants due to the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions in force. Also, we have planned to estimate coverage levels at the state and regional levels only. Therefore, we could not estimate coverage levels at the district level and undertake the comparisons.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, JE vaccination coverage was high in Maharashtra and Telangana states in India. However, the focus needs to be on reducing missed opportunities for routine vaccination. The vaccination effectiveness studies among children could help in explaining the continued occurrence of JE. The impact of JE vaccination on reducing the incidence of disease may be helpful for deciding control strategies.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Babasaheb V. Tandale planned and designed the study including the design, procedures, and questionnaires. Critical review inputs were received from Pradeep R. Deshmukh, Uday W. Narlawar, and Punam Kumari Jha. Additional review, suggestions, and coordination of field activities were received from Rahul Narang, Mohiuddin S. Qazi, and Goteti V. Padmaja as the site investigators. The other investigator colleagues of the study group also provided inputs and support during the study execution (Shilpa J. Tomar, Vijay P. Bondre, Gajanan N. Sapkal, Rekha G. Damle, Poornima Khude, Manoj Talapalliwar, Pragati Rathod, and Kishore Kumar K. J.). Pravin S. Deshmukh drafted the manuscript along with the preparation of illustrations with guidance from Babasaheb V. Tandale and others. Shekhar S. Rajderkar guided, reviewed, and provided inputs on study design, data interpretation, and reporting of findings along with a critical review of the draft report and final manuscript. All authors and study group contributors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the parents and guardians of all children for participation in the study. We acknowledge the financial support from the ICMR. We also thank all state and district health officials for their cooperation during the field survey. We acknowledge the critical review inputs from Dr. Sunil R. Vaidya, ICMR-National Institute of Virology, Pune. We acknowledge the funding from the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India [ICMR/VIR/2/2018/ECD-I].

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The research data are not shared.