The Deltacron conundrum: Its origin and potential health risks

Saria Farheen and Yusha Araf contributed equally to this study.

Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), since its outbreak in December 2019, has been capable of continuing the pandemic by mutating itself into different variants. Mass vaccinations, antibiotic treatment therapy, herd immunity, and preventive measures have reduced the disease's severity from the emerging variants. However, the virus is undergoing recombination among the current two variants: Delta and Omicron, resulting in a new variant, informally known as “Deltacron,” which was controversial as it might be a product of lab contamination between Omicron and Delta samples. However, the proclamation was proved wrong, and the experts are putting more effort into better understanding the variant's epidemiological characteristics to control potential outbreaks. This review has discussed the potential mutations in the novel variant and prospective risk factors and therapeutic options in the context of this new variant. This study could be used as a guide for implementing appropriate controls in a sudden outbreak of this new variant.

1 INTRODUCTION

SARS-CoV-2, since its emergence in 2019, went through various mutations over time. The evolution of the original virus into a new variant may occur for various reasons. Most mutations are only used as barcodes to track epidemics.1 Usually, it is more beneficial for a respiratory virus to evolve to disseminate more easily. Mutations that make a virus more lethal also may limit its ability to spread effectively.1 As a result, COVID-19 mutations usually favor being more infectious than fatal. However, more infections from a rapidly spreading variant will result in more serious reactions, hospitalizations, and deaths. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control claimed these emerging “variants” put more stress on health systems in an immediate risk assessment.

Several factors could drive the viral evolution. These include the selective pressures exerted by host responses, replication in other species and transmission back to humans, prolonged replication in immunocompromised hosts, RNA polymerase mutations that interfere with the virus's proofreading function, or deletions that are not detected by its proofreading machinery.2 The WHO has provided nomenclature systems for tracking these variants and established their genetic lineages using GISAID, Nextstrain, and Pango tools.3 The WHO classified the variants as “variants of interest” (VOIs) and “variants of concern“ (VOCs) so that global monitoring and research sectors can predominantly improve medical facilities to fight the new variants. A VOIs has genetic characteristics that predict greater transmissibility, evasion of immunity, or diagnostic testing. On the other hand, a VOCs is a strain of COVID-19 that has been observed to be more infectious and more likely to cause breakthroughs or re-infections in those vaccinated or previously infected.4 Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta are examples of such variants that appeared in the United Kingdom, South Africa, Brazil, and India in mid and late 2020.

Another VOC, Omicron, came into force in November 2021 in 57 countries. Although no mutation has yet been discovered, such variants are likely to emerge that confers resistance to vaccination. Disease control should remain a top priority to limit the danger of outbreaks and prepare for their consequences.

The Delta (AY.4) variant is a globally prominent variant that has spread to at least 185 nations after being discovered first in India on Jun 15, 2021.5 The WHO and CDC have designated the Delta coronavirus as a “variant of concern” because it appears to be more easily transferred from one person to another. Delta is now the most contagious type of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus as of September 2021. The Delta variant spiked the daily new cases of COVID-19 to approximately 5,517,602, with a death toll of almost 12,897 people globally.6 Soon, on November 26, 2021, another variant emerging in South Africa, “Omicron,” was declared a VOC by WHO.7-9 In South Africa, the epidemiological situation was marked by three peaks in reported cases, previously seen for the Delta strain.10 Many alterations were found in the Omicron (BA.1) strain, which enhanced the chance of re-infection.11, 12

However, recently, on January 7, 2022, virologist Leondios Kostrikis reported that his research group at the University of Cyprus in Nicosia discovered numerous SARS-CoV-2 genomes comprising elements from both the Delta and Omicron forms.13 His research team named it “Deltacron” and soon caught the media's attention globally. Dr. Maria Van Kerkhove, the American infectious disease epidemiologist, opined in this situation that since the virus is circulating a lot, infecting animals to humans, so the pandemic is probably far from over.14 Initially, most experts worldwide considered “Deltacron” as a product of lab contamination. The Delta variant has a mutation in the spike gene that reduces some primers' ability to bind to it. As a result, sequencing this part of the genome becomes difficult.13 Omicron does not have this mutation, so if any Omicron particles get mixed into the sample, it may lead to contamination. Such contamination might make the sequenced spike gene similar to that in Omicron.15 However, on March 9, 2022, the World Health Organization debunked the debacle by stating that new COVID-19 combinations have been detected in France, the Netherlands, Denmark, and the United States. This declaration made the new variant more feasible, and the international surveillance to identify the potential concern variants became stronger.

In this paper, we examine the possible mutations in the new variant and the potential risk factors and provide necessary treatment possibilities in the context of this new variant.

2 THE NEW SARS-COV-2 VARIANT AND ITS EMERGENCE

SARS-CoV-2 is susceptible to genetic mutation, altering the possible transmission mechanism and rate in different variants. As mentioned earlier, the variants have significantly increased the rate of infection, hospitalization, and mortality.16 The spike protein and other genome parts have contained many mutations.17 The genomic variants of SARS-CoV-2 differ from one another in terms of transmission advantage, reproduction numbers (R0), a mutation in the RBD (receptor-binding domain) of the spike protein, and others.18 Genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 viral samples is essential to control the pandemic as it aids in developing vaccinations to combat the ever-emerging variants.19

SARS-CoV-2's spike protein (S) comprises two subunits: S1 and S2. It plays a vital role in receptor recognition and cell membrane fusion. The receptor-binding domain of the S1 subunit identifies and binds to the host receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, whereas the two-heptad repeat domain of the S2 subunit promotes viral cell membrane fusion.20

Some mutations disrupt the coronavirus's spike protein and aid in the virus's attachment to human cells in the nose, lungs, and other body parts.21 According to initial findings, new variants adhere more strongly to our cells. Due to modifications in the spike protein, some of these novel strains appear to be “stickier,” making them more easily transferred. For instance, the variants causing the global winter 2020–2021 wave had an advantage over older variants in immune evasion and rapid transmission due to their increased adherence capacity to the specific domains.22

The most recent variant is “Deltacron,” which has not received any formal name yet and has become the global focus among experts.23 For the time being, the novel hybrid is referred to as the AY.4/BA.1 recombinant by several scientists. The World Health Organization has confirmed its presence and identified it as a hybrid strain that combines both the delta and omicron variants. According to Reuters, at least 17 patients in the United States and Europe have been identified with the new variant.24 As already mentioned, it is a recombinant virus, combining genetic information from both variants—Delta and Omicron.25 Deltacron has almost the full-length spike protein of Omicron and a Delta backbone.25, 26

Although the recorded cases are still few, experts say that analyzing and tracking the potential recombinants are critical to understanding how the coronavirus evolves as the pandemic progresses.

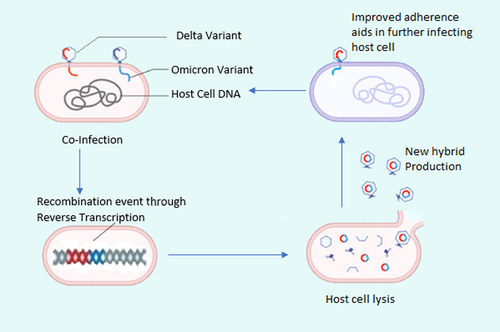

Genetic recombination of human coronaviruses has been known to happen through co-infection or when two variants simultaneously infect the same host cell. It is assumed that two or more SARS-CoV-2 variants might have circulated simultaneously and in the same geographical area during the pandemic. In such situations, viruses might have swapped parts of their genome and picked up mutations from one another as they invaded and replicated within the cell,27, 28 as illustrated in Figure 1.

Such recombination is not uncommon among the coronavirus since the alpha variant was also a product of the recombination from the previous SARS-CoV-2 variants.29 Jeremy Kamil, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Louisiana State University Health Shreveport, also stated that Delta is effectively attempting to keep its head above water by plagiarizing the spike protein from Omicron. Vaccines and other medicines are usually developed to target the spike proteins. Therefore, the virus is constantly experiencing mutations in this region to maintain its viability.15

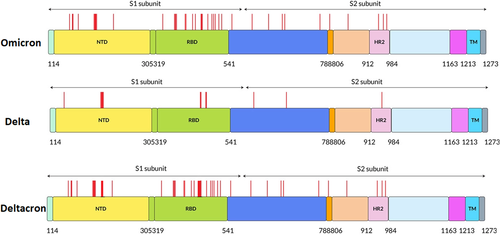

In Deltacron, 36 amino acid mutations were found in the Spike (S) protein. Of these, 27 mutations alone were found in Omicron and five in Delta, while four were found in both.30, 31 Figure 2 shows different amino acid mutations, as seen in red lines, on the S (Spike) protein of Delta, Omicron, and Deltacron variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

The full-length genome of SARS-CoV-2 includes a replicase complex comprising ORF1a and ORF1b (Open Reading Frame) at the 5′UTR. The ORF1a encodes for nonstructural proteins (nsp): nsp1-10, while ORF1b encodes for nsp1–nsp16. In addition, the genome has four other genes encoding the structural proteins: Spike gene (S), Envelope gene (E), Membrane gene (M), Nucleocapsid gene (N), and a poly (A) tail at the 3′UTR. The new recombinant lineage of the Delta (AY.4) genome has acquired an Omicron (BA.1) spike sequence at the nucleotide positions 21,643 to 25,581.32, 33

The discovery of Deltacron sparked extensive media attention and heated debate on social media. Initially, most of the experts considered the contamination of the samples in the laboratory.13 Nevertheless, its presence was confirmed by studying the sequences provided from different authentic sources worldwide.27, 34 Experts believe it is too soon to predict this variant's severity and potential outbreaks since only a few cases have been recorded.35

Nevertheless, increased international surveillance continues to monitor the record of the case.35 Besides, the possibility of cross-species transmission is the most serious concern posed by the emergence of these novel hybrid viruses. The ongoing investigation of this virus will determine whether it is a variant of concern and the threats it will pose.

3 THE RISK ASSESSMENT OF THE NEW VARIANT

Experts think it is too early to say whether Deltacron has a different effect on people than the Delta or Omicron variants, mostly because the variant has not caused any notable spikes in cases or deaths anywhere in the world yet. In this context, the bioinformatician at the Washington, DC, Public Health Laboratory, Scott Nguyen, said, “Deltacron cases are also thought to be rare, and there is no indication yet that the hybrid is fueling big spikes in infection.”15 He added that there is less chance of possible outbreaks from this variant since antibodies and other immune responses against Omicron should work on this recombinant.36 Besides, Omicron's characteristic spike protein also plays a role in its lower risk of triggering serious sickness.37 The spike protein can successfully infect the nose and upper airway cells but not deep in the lungs. Thus, the new recombinant may display the same action.36 However, researchers worldwide are conducting tissue culture experiments to examine Deltacron's impacts on human cells and compare it to the delta and omicron strains.38

The experts also think the new variant can be as transmissible as Omicron since it has a surface spike protein similar to Omicron.14 The Omicron's spike protein could partially evade the immune system and even polyclonal antibody responses, allowing re-infection and vaccine development.39 Therefore, similar abilities can be predicted for the new variant, so necessary precautions should be adopted.

The new variant has a virion structure similar to the Delta variant, suggesting that the Deltacron might be dangerous just like the delta variant. The Delta strain caused India's deadly second pandemic wave beginning in February 2021.40 As of September 2021, Delta is regarded as the most contagious form of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus.41 Thus, proper actions should be taken as soon as possible to combat a sudden surge caused by the new variant.

William Hanage, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, believes that the deltacron can be considered a variant only if it generates a lot of cases.4 So, people should not be concerned if it does not cause many cases. According to WHO, there were 8,997,674 new cases of COVID-19 globally, of which only 17 cases were from Deltacron.10 According to WHO, no change in severity has been documented, and more research is being conducted to learn more about the variant.10 From the recent updates at GISAID (April 4, 2022), 74 cases have been found in France, 8 in Denmark, 3 in Germany, Netherlands, and Belgium.34 From the map in Figure 3, it can be seen that the prevalence of the virus is only limited to a few European countries so far.

Moreover, no deaths from this new variant have been recorded anywhere globally. Therefore, the new variant seems to be less virulent and less transmissible. However, the potential “Deltacron” cases are being monitored, and symptoms such as sore throat, headache, runny nose, fever, and loss of taste or smell from the previous variants have been found.23 Therefore, coronavirus prevention measures and mass vaccinations must be continued to control the new variant's regulation.

4 PREVENTION AND TREATMENT

It has been established that vaccination is the best protection against the SARS-CoV 2 infection. According to the physicians, the most important thing to protect oneself from Delta, Omicron, or any COVID-19 form, is to get properly vaccinated.42 Recommendations for boosters and those eligible to get one have changed, and authentic resources are available.43 Vaccinating against COVID-19 is a better strategy to establish immunity than getting sick with COVID-19. COVID-19 vaccine protects us by eliciting an antibody response without causing the illness. Humoral immunity, mostly neutralizing antibodies, has been identified as a major correlate of protection from COVID-19.44 Virus-neutralizing monoclonal antibodies are predicted to reduce viral load, alleviate symptoms, and prevent hospitalization. Single and combination monoclonal antibody therapy has been approved for emergency use, and further treatments are being developed.45

However, according to new research, COVID-19 vaccinations become less effective at preventing infection or serious illness, especially in persons 65 and older, so people over 12 who have finished their initial immunization series should get booster injections.46

Although COVID-19 immunizations are extremely efficient at preventing serious disease and death, some people will still become ill after receiving the vaccine. Infected people may spread the infection to people who have not been vaccinated.47 Furthermore, simulations suggest that immunization reduces the risk of the emergence of a vaccine-resistant strain if transmission control measures are maintained throughout the vaccination campaign.48, 49 As a result, it is very important to continue practicing preventive measures besides getting vaccinated. Preventive measures include physical distancing, wearing a well-fitted mask with clean hands, avoiding crowds, and improving ventilation where we live, work, and study. The biggest factor is to ensure reduced exposure to the virus, no matter what variant is circulating.

5 CONCLUSION

The SARS-CoV-2 virus is thriving through mutations to continue the current pandemic. Under such a situation, it is quite evident that the virus may mutate into more new variants shortly. However, the herd immunity developed through mass vaccination and natural infection, the practice of preventive measures, and the development of different other treatments might be able to combat the severity of the upcoming variants. The increasing genetic diversity of SARS-CoV-2, international and national surveillance of the infections, and the global genome sequencing effort will increase the chances of detecting new recombinants. Thus, such measures will allow researchers to determine the SARS-CoV-2 recombination rate, potential recombination hotspots, and the extent of recombination that generate future pandemic variants.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Yusha Araf conceived the study. Yusha Araf and Saria Farheen designed the study. Yusha Araf and Chunfu Zheng supervised the study. Saria Farheen wrote the preliminary draft manuscript. Saria Farheen illustrated the figures. Chunfu Zheng and Yusha Araf reviewed the preliminary draft manuscript. Saria Farheen, Yusha Araf, Yan-Dong Tang, and Chunfu Zheng edited, revised, and finalized the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

This is a review article, and no new data were generated or analyzed in this study. Therefore, data sharing does not apply in this article.