Variants of concern responsible for SARS-CoV-2 vaccine breakthrough infections from India

Urvashi B. Singh and Mercy Rophina contributed equally to this study.

The members of the COVID CBNAAT CORE GROUP are listed in the Supplementary Appendix.

Vinod Scaria and Sridhar Sivasubbu are senior authors and they equally contributed to this study.

Abstract

Emerging reports of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections entail methodical genomic surveillance for determining the efficacy of vaccines. This study elaborates genomic analysis of isolates from breakthrough infections following vaccination with AZD1222/Covishield and BBV152/Covaxin. Variants of concern B.1.617.2 and B.1.1.7 responsible for cases surge in April–May 2021 in Delhi, were the predominant lineages among breakthrough infections.

1 INTRODUCTION

Vaccines have been one of the most powerful weapons against infectious diseases. The emergence of COVID-19 as a global pandemic has seen accelerated development as well as regulatory approvals for a variety of vaccines across the world. Immunity acquired from natural COVID-19 infection or vaccines is not absolute and reinfections postnatural COVID-19 infections, as well as vaccine breakthrough infections, are not uncommon.1-3 The recent evidence from the United States suggests vaccine breakthrough infections to be approximately 0.01% in fully vaccinated populations.4 One of the initial surveillance reports from a chronic care medical facility in India reported out of a total of 113 employees, 19 experienced vaccine breakthrough infections.5

Genomic surveillance of vaccine breakthrough infections can provide useful insights into the genetic variants of SARS-CoV-2 that caused the infection.2, 3 In this study, we describe the genomic analysis of a cohort of COVID-19 vaccine breakthrough infections in a tertiary health care centre in Delhi, India. The samples included in the study coincided with a COVID-19 cases surge in the state during the months of April and May 2021.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study approval

Samples were collected as part of routine testing for patients reporting to the Emergency Department at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, with symptoms of high-grade fever, shortness of breath, and headache. The samples were subjected to whole-genome sequencing following the IEC approvals (IEC-679/03.07.2020, RP-32/2020).

All individuals who completed the schedule of vaccine and tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction test (Genexpert SARS-CoV-2, Cepheid and TRUNAT Beta-CoV, Molbio India), were included in the analysis. The cohort was subdivided into two groups depending on whether they received only one dose or both doses as per the vaccination schedule. Additional metadata, including the dates of vaccination, type of vaccine received, dates of testing positive and clinical information, such as symptoms and history of forward transmission as well as occupation were elicited. All samples which did not satisfy the criteria or patients who could not be reached were duly excluded.

The daily COVID-19 cases in Delhi were retrieved from an open resource.9 Genomic data sets covering the period were also retrieved from Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID)10 (Supporting Information Data 1) for comparison on variant profiles.

Whole-genome sequencing was performed on the SARS-CoV-2 positive RNA samples, using the COVIDSeq Test (Illumina Inc.) assay in NovaSeq. 6000 platform adopting a paired-end sequencing approach with 50*2 read length 12 and analysed as per published protocol.11

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

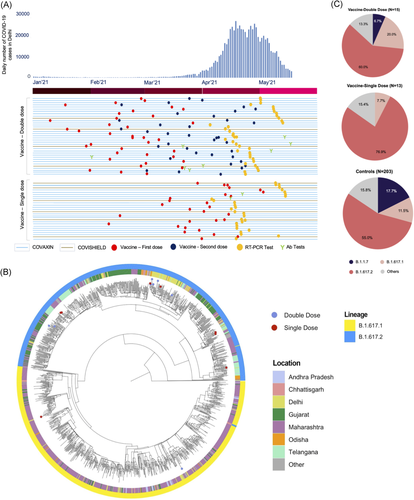

Our analysis included 63 cases of vaccine breakthrough infections for which the dates of vaccines could be ascertained, of which 36 patients received two doses, while 27 had received one dose of vaccine. Ten patients received AZD1222/Covishield while 53 received BBV152/Covaxin. The timeline for vaccination and infection in the context of the surge in cases in Delhi is summarised in Figure 1A. The patients had a mean age of 37 (21–92), of which 41 were males and 22 were females. None of the patients had any comorbidities which could act as a predisposing factor for breakthrough infections.

The mean depth of coverage of the genome sequences for the 63 viral isolates was 3953X (108.7X–17,435.5X) and it correlated with the viral load as reflected by the Ct values. The patient details and genomic data are summarised in Table S1. A phylogenetic tree was constructed following a previously published protocol6 using B.1.617.1 and B.1.617.2 genomes from India submitted to GISAID. Genome sequences of 16 of the 63 viral isolates that had ≤2000 ambiguous bases were included in the phylogenetic analysis. The clustering of the 16 samples on the phylogenetic tree is suggestive of multiple independent sources of infection for the patients analysed. The phylogenetic context of the samples sequenced is summarised in Figure 1B.

Lineages were systematically assigned to the genomes analysed in this study using pangolin 2.4 (pangoLEARN version 2021-04-28).7 SARS-CoV-2 lineages could be assigned for a total of 36 (57.1%) samples, 19 (52.8%) in patients who completed both doses and 17 (47.2%) in patients who completed only a single dose. B.1.617.2 was found to be the predominant lineage with 23 samples (63.9%) out of which 12 were fully vaccinated and 11 in partially vaccinated groups, 4 (11.1%) and 1 (2.8%) samples were assigned the lineages B.1.617.1 and B.1.1.7, respectively. The B.1.617.2 lineage was first described in India and associated with increased transmissibility as well as immune escape and has grown to become one of the predominant lineages in India.

Additional samples covering the respective period (March 28, 2021–April 30, 2021) from Delhi with no prior vaccination information, deposited in GISAID were used as the control data set. As lineage B.1.617.2 was also prevalent in this group, any significant differences in lineages among fully and partially vaccinated samples were analysed. The difference was not found to be significant in both double-dose vaccinated and single-dose vaccinated groups (Vaccine-double dose: χ2 corrected = 0.0112, pval = 0.9159; Vaccine-single dose: χ2 corrected = 3.2441, pval = 0.0717). The proportions of lineages are summarised in Figure 1C. In addition, differences in the prevalence of lineages based on the type of vaccines were also checked. There was no significant difference observed (χ2 corrected = 0.0586, pval = 0.8087).

Of the breakthrough infection cases analysed, 10 patients (eight with double doses of vaccine and two with single vaccine dose) additionally had total Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies assessed by Chemiluminescent Immunoassay (Siemens), of which six patients had IgG antibodies a month before the infection, while four had antibodies after the disease episode.

Viral load at the time of diagnosis was high in all the patients irrespective of vaccination status or type of vaccine received. The initial course of disease with high-grade nonremitting fever lasted for 5–7 days in the vaccinated group, similar to the clinical presentation in unvaccinated patients. During the subsequent course of illness, neither disease worsening (stable biomarkers) nor mortality was reported in the present group, confirming the previous observations.

The patients included health care workers (24, 13 of which were from the same hospital) and close analysis of the genomic sequences suggests that the samples clustered separately with origins closely clustering with lineages from different states, suggesting the disease transmission happened most likely from different and independent sources.

Reinfections and vaccine breakthrough infections are rare occurrences and genomic sequencing of vaccine breakthrough infections can provide useful insights. In the present group of vaccine breakthrough infections investigated using genome sequencing, closely overlapping and mirroring the COVID-19 cases in the state of Delhi, the variants of concern B.1.617.2 and B.1.1.7 comprised the majority, but the proportions were not significantly different in comparison with the population prevalence of the variants during this period with high community transmission. Breakthrough infections reported to CDC have primarily been attributed to variants of concern and the proportion was similar to the prevalence throughout the United States, again during a period of high transmission.4 While a number of vaccine breakthrough infections have been reported previously, it has been largely associated with nonsevere symptoms. Mortality due to COVID-19 was ascribed to 2% cases (primarily older population, average age = 82 years).4 Of the 63 cases of vaccine breakthrough infections in the current study, including 36 who received full doses, there are no reports of mortality even though almost all cases presented with high-grade unremitting fever for 5–7 days. While total antibody levels for a subset of patients were high, they became infected nevertheless and presented to the emergency just like other patients, putting in doubt the protection offered and or clinical relevance of total IgG as a surrogate of COVID-19 immunity.

The present report is unique in many aspects. This is one of the first reports of symptomatic vaccine breakthrough infections, and breakthrough infections in a tertiary care setting apart from being the earliest reports of breakthrough infections with BBV152/Covaxin and B.1.617.2 variant of SARS-CoV-2. This report brings forth the role of highly transmissible variants of concern in causing breakthrough infections in the vaccinated population.3, 8 We hope this early report of genomic analysis of breakthrough infections could provide guidance to further systematic cohort analysis on the efficacy of vaccines with respect to genetic variants of SARS-CoV-2.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors acknowledge funding from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR India) through grants CODEST and MLP2005. BJ, MKD, AB, AJ acknowledge fellowship from CSIR India. SS acknowledges the J C Bose Fellowship of the Dept of Science and Technology, India. See Supplemental appendix for COVID CBNAAT CORE GROUP details.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Urvashi B. Singh formulated the study with Vinod Scaria and Subrata Sinha. Urvashi B. Singh and Vinod Scaria planned the work and wrote the manuscript with Mercy Rophina. Urvashi B. Singh, Rama Chaudhry, Kiran Bala, Subrata Sinha, and Ritu Gupta contributed to diagnostics, laboratory management. COVID CBNAAT CORE GROUP conducted diagnostic tests. Nayer Jamshed, Praveen Aggarwal, and Ritu Gupta contributed to clinical data collection and clinical care. Vigneshwar Senthivel, Rahul C. Bhoyar, Mohit K. Divakar, Mohamed Imran, and Anjali Bajaj contributed to the NGS data generation under the guidance of Subrata Sinha. Mercy Rophina, Bani Jolly, and V. R. Arvinden, Afra Shamnath, and Abhinav Jain contributed to the data analysis. Urvashi B. Singh conceived the project and followed up the clinical data and Mercy Rophina was involved in genomic data analysis.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The sequence data is available in GISAID (https://www.gisaid.org) with IDs EPI_ISL_2426235- EPI_ISL_2426245.