Prevalence and molecular characterization of human rhinovirus in stool samples of individuals with and without acute gastroenteritis

Abstract

Human rhinovirus (RV) most often causes mild upper respiratory tract infection. Although RV is routinely isolated from the respiratory tract, few studies have examined RV in other types of clinical samples. The prevalence of RV was examined in 1,294 stool samples collected mostly from children with acute gastroenteritis residing in Bangkok and Khon Kaen province of Thailand between January 2010 and October 2014. In addition, 591 samples from hand–foot–mouth disease (HFMD) or herpangina patients who do not have gastroenteritis served as a comparison group. Samples were initially screened by semi-nested PCR for the RV 5′UTR through the VP2 capsid region. RV genotyping and phylogenetic analysis were performed on the VP4/VP2 regions. Among children with acute gastroenteritis, RV was found in 2.3% (30/1,294) of stool samples, which comprised 47% (14/30) RV-A, 17% (5/30) RV-B, and 37% (11/30) RV-C. In the comparison group, 0.8% (5/591) was RV-positive and RV-C (3/5) was the major species found. Interestingly, RV was recovered more often from children with acute gastroenteritis than from those with HFMD or herpangina. As many as 31 RV types were present in the gastroenteritis stools, which were different than the types found in those with HFMD or herpangina. J. Med. Virol. 89:801–808, 2017. © 2016 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Human rhinovirus (RV) and enterovirus belong to the genus Enterovirus within the large Picornaviridae family. RVs are the major cause of mild upper respiratory tract infections and the common cold [Brownlee and Turner, 2008]. They are also responsible for lower respiratory tract infections such as pneumonia [Abzug et al., 1990], bronchiolitis [Jartti et al., 2004], and wheezing [Duff et al., 1993]. RV infection exacerbates asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [Nicholson et al., 1993]. Additionally, RVs are associated with the severity of acute otitis media [Pitkäranta and Hayden, 1998] and sinusitis [Pitkäranta et al., 1997].

RV is an icosahedral virus containing positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome of approximately 7.2 kb. All the structural proteins are encoded in the P1 region, while the P2 and P3 regions encode seven nonstructural proteins (2A–C and 3A–D). Historically, RVs have been classified based on the receptor usage [Uncapher et al., 1991] and anti-viral drug sensitivity pattern [Andries et al., 1990]. There are currently more than 100 distinct RV types as virus classification utilizes phylogenetic analysis of the capsid coding regions VP1 and VP4/VP2. RVs can be divided into three species designated RV-A, RV-B, and RV-C, which collectively comprise approximately 80 serotypes, 32 serotypes and 54 types, respectively [McIntyre et al., 2013].

Enteroviruses replicate in the gastrointestinal tract as they are acid-resistant and can maintain viral infectivity even at pH < 3. In contrast, RVs are not believed to infect the gastrointestinal tract because the virus is labile to the acidic environment of the stomach. Conformational changes in the viral capsid proteins at low pH can cause the VP4 subunit to be destroyed, which renders the loss of viral infectivity [Giranda et al., 1992]. Additionally, the optimum temperature for RV replication is 33–34°C generally found in the respiratory tract [Papadopoulos et al., 1999]. Although RV is not expected to survive the digestive tract, it has been detected in both the nose and stool specimens taken at the same time [Savolainen-Kopra et al., 2013] and in sewage during surveillance of enteroviruses [Blomqvist et al., 2009]. Interestingly, high enterovirus and RV viral loads have frequently been detected in stool samples from individuals with gastroenteritis [Harvala et al., 2012; Honkanen et al., 2013; Savolainen-Kopra et al., 2013]. Since epidemiological data on RV among acute gastroenteritis patients remain limited especially in tropical countries, we investigated the prevalence and characterized RV genotypes in stool samples obtained from Thai individuals with acute gastroenteritis. In comparison, we also evaluated the presence of RV in patients with hand–foot–mouth disease (HFMD) or herpangina, which are typically not associated with acute gastroenteritis.

METHODS

Patient Samples

The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University (IRB number 491/57). This study was conducted on archived specimens collected upon routine examinations and stored as anonymous. Permission to use these convenient samples had been granted by the Director of King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital. Patient identifiers including personal information (name, address) and hospitalization numbers were removed from these samples to protect patient confidentiality. IRB waived the need for consent because the samples were de-identified.

A total of 1,294 stool samples from patients with acute gastroenteritis collected for a routine rotavirus surveillance protocol were examined. Inclusion criteria were acute gastroenteritis with diarrhea, fever and/or vomiting. Samples were from Bangkok and Khon Kaen province in Thailand and obtained during a 58-month period (January 2010 and October 2014). The patient age ranged from 1 day to 97 years (mean age = 4.8 years; age under 5 years = 83.5% of samples). Also in this study, we analyzed additional 591 stool or rectal swab samples from patients with HFMD or herpangina who did not have gastroenteritis and were referred from the routine enterovirus surveillance protocol. Samples were collected from Bangkok, Khon Kaen, and Suphan Buri during a 34-month period (January 2012 and October 2014). The patient age ranged from 1 day to 39 years (mean age 3.4 years; age under 5 years = 73.4%).

Enteric viruses including human rotavirus (HRoV), human parechovirus (HPeV), human norovirus (HNoV), human adenovirus (HAdV), and human bocavirus (HBoV) were screened according to previously described protocols [Chieochansin et al., 2008; Chieochansin et al., 2011; Maiklang et al., 2012; Sriwanna et al., 2013]. All samples were anonymized, but clinical information from individuals with acute gastroenteritis was retained.

Nucleic Acid Extraction and Reverse-Transcription

Samples were diluted with PBS, clarified by centrifugation, and the supernatants stored at −70°C until RNA extraction. Total viral nucleic acid was extracted using a commercial kit (GeneAll, Seoul, Korea) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Complementary DNA was synthesized from 5 μl of RNA with random hexamers using ImProm-II Reverse Transcription System (Promega, Madison, WI).

Detection of RV VP4/VP2 and 5′UTR Regions

RV genomes were detected by semi-nested PCR using primers specific to 5′UTR and VP2 gene as previously described [Linsuwanon et al., 2009]. In the first PCR, forward primer F484 (5′-CGGCCCCTGAATGYGGCTAA-3′, nt 451–470) bound the 5′UTR, while the reverse primer R1126 (5′-ATCHGGHARYTTCCAMCACCA-3′, nt 1,061–1,081) bound VP2 region. In the second PCR, the forward primer F587 (5′-CTACTTTGGGTGTCCGTGTTTC-3′, nt 544–565) was used in combination with primer R1126. The given nucleotide positions were based on a RV-35 reference strain ATCC VR-1145 (GenBank accession number FJ445187). The PCR reaction mixture contained 2 μl of cDNA, 0.5 μM of forward and reverse primers, 10 μl of 1X PerfectTaq MasterMix (5 PRIME, Darmstadt, Germany), and nuclease-free water adjusted to a final volume of 25 μl. The PCR conditions were 94°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. The expected 538 bp amplicon was agarose gel-purified and submitted for sequencing.

RV-positive samples were further analyzed for sequence in the 5′UTR region (nt 177–559) using primers RV-OL 26 (5′-GCACTTCTGTTTCCCC-3′) and RV-OL 27 (5′-AGGACACCCAAAGTA-3′) [Kim et al., 2013]. PCR parameters were 94°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 20 sec, 52°C for 40 sec and 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. The expected 383 bp amplicon was also agarose gel-purified and sequenced. All RV nucleotide sequences for VP4/VP2 gene were deposited in the GenBank database (accession numbers KR054522-KR054554, KR922045, and KR922046). Nucleotide sequences for the 5′UTR were submitted under accession numbers KR054555–KR054585.

Genome Characterization, Phylogenetic, and Recombination Analyzes

RV nucleotide sequences were analyzed using Chromas Lite (v2.01) and BioEdit program (v7.2.5), and virus types determined using NCBI BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Phylogenetic trees of the 5′UTR and VP4/VP2 sequence were generated using Clustal W and neighbor-joining method with 1,000 bootstrap values implemented in MEGA (v5.05) [Tamura et al., 2011]. To examine the recombination events, sequences in the nt 177–1081 region were analyzed using SimPlot (v3.5.1) and RDP (v4.46) programs [Martin et al., 2010].

Differences in age groups, sex, and seasonal prevalence were analyzed using SPSS software (v22). Comparisons were evaluated using the chi-squared test. Statistical significance was established at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Detection of RV Sequences in Clinical Samples

Most of the individuals with acute gastroenteritis or HFMD/herpangina were young males <5 years old (Table I). A total of 30 samples tested positive for RV from the acute gastroenteritis samples (2.3%). RV was found mostly in samples from children ≤2 years of age (87%, 26/30), followed by 2–5 years old (6.7%, 2/30), and in more males (83%, 25/30) than females (17%, 5/30) (gender ratio 5:1) (P < 0.05). Meanwhile, only five samples from patients with HFMD/herpangina were RV-positive (0.8%).

| Stool samples from acute gastroenteritis (n = 1,294) | Stool samples from hand–foot-mouth disease or herpangina (n = 591) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RV positive | RV positive | |||||||||

| No. of samples (%) | RV-A (n = 14) | RV-B (n = 5) | RV-C (n = 11) | Total (n = 30), no. (%) | No. of samples (%) | RV-A (n = 1) | RV-B (n = 1) | RV-C (n = 3) | Total (n = 5), no. (%) | |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 781 (60.4) | 9 | 5 | 11 | 25 (83) | 301 (50.9) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 (40) |

| Female | 509 (39.3) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 (17) | 249 (42.1) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 (60) |

| N/A | 4 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) | 41 (6.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| 0 to <2 | 899 (69.5) | 12 | 5 | 9 | 26 (87) | 187 (31.6) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 (60) |

| 2 to <5 | 181 (14) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 (6.7) | 247 (41.8) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (20) |

| 5 to <15 | 40 (3.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) | 74 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| ≥15 | 84 (6.5) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.3) | 11 (1.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| N/A | 90 (7) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.3) | 72 (12.2) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (20) |

| Mean (SD) | 4.8 (13.5) | 5.7 (17.2) | 0.9 (0.74) | 1.2 (1.1) | 3.1 (12) | 3.4 (4.1) | N/A | 2 (N/A) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.5) |

| Season (months) | ||||||||||

| Summer (Feb–Apr) | 451 (34.9) | 5 | 4 | 4 | 13 (43) | 38 (6.4) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (20) |

| Rainy (May–Oct) | 492 (38) | 5 | 0 | 3 | 8 (27) | 484 (81.9) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 (80) |

| Winter (Nov–Jan) | 351 (27.1) | 4 | 1 | 4 | 9 (30) | 69 (11.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

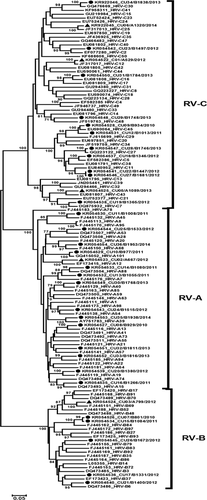

Analysis of the nucleotide sequences of the VP4/VP2 region compared to the RV reference strains available from GenBank identified 31 different RV types among the 35 RV-positive samples. Approximately, half were members of RV-A, while RV-B strains were the least common types (Table II). Two samples each of RV-A88, RV-B84, RV-C11, and RV-C45 were detected in the acute gastroenteritis samples. RV genotypes were additionally confirmed by phylogenetic analysis, which showed that the 30 RV strains from acute gastroenteritis samples clustered within RV-A (47%, 14/30), RV-B (17%, 5/30), and RV-C (37%, 11/30) (Fig. 1). Meanwhile, 5 RV strains from HFMD or herpangina samples were classified as RV-A and RV-B equally at 20% (1/5), and RV-C at 60% (3/5).

| Children with acute gastroenteritis (n = 30) | HFMD or herpangina patients (n = 5) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RV-A | RV-B | RV-C | RV-A | RV-B | RV-C | ||||||

| Strain | No. (+) | Strain | No. (+) | Strain | No. (+) | Strain | No. (+) | Strain | No. (+) | Strain | No. (+) |

| RV-A13 | 1 | RV-B6 | 1 | RV-C2 | 1 | RV-A12 | 1 | RV-B69 | 1 | RV-C12 | 1 |

| RV-A15 | 1 | RV-B37 | 1 | RV-C5 | 1 | RV-C25 | 1 | ||||

| RV-A19 | 1 | RV-B79 | 1 | RV-C7 | 1 | RV-C43 | 1 | ||||

| RV-A39 | 1 | RV-B84 | 2 | RV-C11 | 2 | ||||||

| RV-A40 | 1 | RV-C16 | 1 | ||||||||

| RV-A45 | 1 | RV-C27 | 1 | ||||||||

| RV-A53 | 1 | RV-C30 | 1 | ||||||||

| RV-A54 | 1 | RV-C45 | 2 | ||||||||

| RV-A57 | 1 | RV-C48 | 1 | ||||||||

| RV-A68 | 1 | ||||||||||

| RV-A88 | 2 | ||||||||||

| RV-A94 | 1 | ||||||||||

| RV-A101 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Total | 14 | 5 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||

Seasonal Prevalence of RV

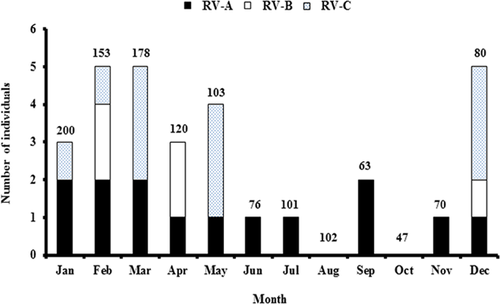

Seasons in Thailand are categorized as summer (February–April), rainy (May–October), and winter (November–January). Among acute gastroenteritis samples, RVs were detected throughout the year with no seasonal clustering. Distribution of RVs by month showed that RV-A occurred throughout the year except for August and October (Fig. 2). Meanwhile, RV-B and RV-C were absent between June and November. The calculated annual prevalence of RV were 1.1% (3/268) in 2010, 2.2% (7/315) in 2011, 2.7% (11/403) in 2012, 4.3% (7/161) in 2013, and 1.4% (2/147) in 2014. Among HFMD or herpangina samples, however, there were no RV-positive samples during the winter months.

Clinical Characteristics of RV Infection Among Acute Gastroenteritis Patients

Since all acute gastroenteritis samples were previously screened for several viral pathogens, the presence of other viruses among RV-positive samples was examined. RV was the only virus detected in 15 of 30 samples, while the remaining 15 RV-positive samples showed the presence of other viruses (six samples with one other virus, eight samples with two other viruses, and one sample with three other viruses). Viruses most frequently found with RV were HRoV (93%, 14/15), HPeV (33%, 5/15), HBoV (13%, 2/15), HNoV (13%, 2/15), and HAdV (13%, 2/15).

In addition to acute gastroenteritis symptoms (diarrhea and vomiting), clinical data available for 20 RV-positive individuals showed fever (75%, 15/20), upper respiratory tract infection (25%, 5/20), pneumonia (30%, 6/20), and acute bronchiolitis (10%, 2/20) (Table III). Overall, 65% (13/20) of acute gastroenteritis patients had a respiratory tract infection. The average length of hospitalization was 3.8 ± 3.3 days, but longer in individuals with detectable RV-B.

| Clinical characteristics | RV-A (n = 7) | RV-B (n = 5) | RV-C (n = 8) | Total (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial body temperature (°C) | 37.9 ± 0.6 | 37.5 ± 0.9 | 37.5 ± 0.9 | 37.7 ± 0.8 |

| Diagnosis, no. (%) | ||||

| Fever | 6 (86) | 4 (80) | 5 (63) | 15 (75) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 0 (0) | 2 (40) | 3 (38) | 5 (25) |

| Acute bronchiolitis | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 1 (13) | 2 (10) |

| Pneumonia | 3 (43) | 1 (20) | 2 (25) | 6 (30) |

| Acute gastroenteritis | 6 (86) | 5 (100) | 8 (100) | 19 (95) |

| Average length of hospitalization in days (±SD) | 2.9 ± 1.8 | 6.8 ± 5 | 3.3 ± 3 | 3.8 ± 3.3 |

Phylogenetic Analysis of the 5′UTR Region

To determine if any RV strains identified were recombinants, the sequence between nt 177–559 in the 5′UTR was examined in parallel with the VP4/VP2 region (Supplemental Fig. S1). Among 35 RV-positive samples, 5′UTR nucleotide sequences from 31 samples were successfully obtained. Initial phylogenetic analysis of the 5′UTR showed slightly different branching and clustering compared to that of the VP4/VP2 region because there were variants of RV-C with sequence similarities in the 5′UTR to RV-A (referred to as RV-Ca) instead of RV-C itself (defined as RV-Cc). Thus, several RV-C strains clustered within RV-A when examining the 5′UTR sequence alone. This complicated an objective comparison because several closely matched reference strains lacked sequence information in the 5′ terminal region of the genome (between the 5′UTR and VP4/VP2 region) in the database.

To enable a fair comparison between two phylogenetic trees, the complete genomes of other RV reference strains in which the 5′UTR to VP4/VP2 sequences were available (but showed slightly lower identities) were used. The resulting phylogenetic trees of the VP4/VP2 and the 5′UTR regions showed discordance in 3 out of 31 (9.7%) RV strains. Two strains were classified as RV-C11 (probable Ca subspecies) by the VP4/VP2 tree, while the 5′UTR tree classified them as RV-C35 (probable Cc subspecies). Additionally, one strain was classified as RV-B79 by the VP4/VP2 tree, while the 5′UTR tree classified it as RV-B37. Taken together, a total of three strains showed evidence of mixed genomes suggestive of RV recombinants.

RV Recombination Analysis

To confirm possible intraspecies recombination, the nucleotide sequences spanning the 5′UTR to VP4/VP2 (nt 177–1,081) from the above three strains (GenBank accession numbers KR922047–KR922049) were subjected to similarity plot and bootscan analyzes. Strains designated CU09/B934/2010 (Supplemental Fig. S2) and CU12/B1013/2011 (Supplemental Fig. S3) demonstrated recombination between RV-C11 and RV-C35 at nt positions 573 and 570, respectively. This area encompassed the polypyrimidine tract and the SL6 region of the internal ribosome entry site (IRES). Additionally, strain CU26/B1672/2012 showed recombination between RV-B79 and RV-B37 at nt position 606, which is located in the intervening sequence of the 5′UTR (Supplemental Fig. S4). Recombination analyzes using six methods within the RDP program showed statistical significance (P < 0.05) (Supplemental Table SI).

DISCUSSION

RV causes respiratory illness and infection can be particularly severe in children. Previously, the prevalence of RV was characterized from the nasopharyngeal aspirates among children with acute lower respiratory tract infection. Here, the presence of RV in patients with acute gastroenteritis was examined to assess its distribution and the viral diversity in this cohort. As a comparison, the presence of RV in HFMD or herpangina samples, conditions not commonly associated with enteric infection, was also examined. Overall, RVs were detected throughout the year with RV-A being the most prevalent type found among the samples. Even though sample sizes were different between the two cohorts, RVs were detected at least twice as often in acute gastroenteritis samples compared to non-gastrointestinal samples.

RV in stool samples have previously been examined in Finland, Italy, Hong Kong, and the United Kingdom (Table IV). In this study, types of RV found in the stool were as diverse as those previously identified in the respiratory samples [Daleno et al., 2013; Kiyota et al., 2014]. In all, as many as 31 different RV types from all three species of RV were identified by their sequences in this study. Our prevalence of RV-A (46.7%), RV-B (16.7%), and RV-C (36.7%) were similar in proportions to the stool sample screening in the U.K. (46%, 13%, and 41%) [Harvala et al., 2012] and similar to respiratory sample screening in Mongolia (47.1%, 8.2%, and 44.7%) [Tsatsral et al., 2015] and China (50%, 10.4%, and 39.6%) [Zeng et al., 2014]. RV-A was also the most prevalent species found in the stool samples of Finnish children [Honkanen et al., 2013]. While RV was found throughout the year, in Finland it appeared to peak in autumn and sometimes spring [Honkanen et al., 2013; Savolainen-Kopra et al., 2013]. Although there were not many RV-positive samples in this study, they were associated with male gender in contrast to the Finnish study where RV were likely in both genders [Honkanen et al., 2013]. An earlier study suggested that women may have stronger adaptive immune response to RV infection than men and may in part explain why RV infection was detected significantly more often in males than females [Carroll et al., 2010].

| RV positive (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Methods | No. of samples | RV-A | RV-B | RV-C | Total (%) | References |

| Gastroenteritis | Nested RT-PCR | 288 | 41 | 13 | 46 | 10.4 | Harvala et al. [2012] |

| Gastroenteritis | RT-PCR | 734 | – | – | – | 7.9 | Lau et al. [2012] |

| Gastroenteritis | Real-time RT-PCR | 689 | – | – | – | 5.2 | Rovida et al. [2013] |

| Healthy children | RT-PCR | 4184 | 79 | 8 | 13 | 10.5 | Honkanen et al. [2013] |

| Upper respiratory infections and gastrointestinal symptoms | Real-time RT-PCR | 425 | 54 | 23 | 15 | 35.1 | Savolainen-Kopra et al. [2013] |

Although the association between RV and enteric diseases has not been firmly established, it is intriguing that approximately 70% of RV-positive individuals frequently presented diarrhea without any respiratory symptoms or detectable co-pathogens [Harvala et al., 2012]. Similarly, three-quarters of children with RV-C-positive stool samples had diarrhea in the absence of respiratory symptoms [Lau et al., 2012]. In this study, 40% of RV-positive cases with acute gastroenteritis did not show respiratory tract illness. In patients who had RV single infection, seven cases had respiratory symptoms and diarrhea, whereas two cases had diarrhea alone. It would have been ideal to examine the possibility that RV-positive stools resulted from swallowed respiratory secretions, but the respiratory samples of these RV positive cases were not available for testing. Nevertheless, the frequency of RV detected among the HFMD/herpangina patients was lower than that of acute gastroenteritis patients.

RNA viruses including RVs may prove adaptable in replicating in the gastrointestinal tract, which could explain detection in the stool. In vitro studies observed that a single amino acid change in the VP1 region of RV-B14 enabled viral resistance to inactivation at pH 4.5 [Skern et al., 1991]. RV-A89 and RV-B42 isolated from fecal specimens showed cytopathic effect in cell culture, indicating the presence of viable RV in fecal specimens [Honkanen et al., 2013; Savolainen-Kopra et al., 2013]. These studies suggest that certain RV types may be infecting the intestinal cells or at the very least survive the gastric tract. Although we confirmed that RV can be detected in the stool, even from individuals without gastroenteritis, there remains no conclusive evidence to support the active replication of RV in the gastrointestinal tract.

Recombination is known to influence the evolution of viruses and RV-C recombinants involving the 5′UTR were identified in this study. This genomic region consists of two secondary structures; the first is the 5′ clover leaf-like motif or oriL, which plays a role in the viral replication [Borman and Jackson, 1992]. The other is the IRES, which is important in the viral translation. The recombination of RVs has been widely investigated in strains isolated from respiratory samples, but not often for RV isolated from stool samples [Huang et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2013]. We found two intraspecies recombination points in RV-C located in the PPT-SL6 region of the IRES, which have previously been described [McIntyre et al., 2010]. Less frequent was the intraspecies recombination of RV-B. Frequent recombination between RV-A and RV-C at specific sites within the 5′UTR may be influenced by sequence compatibility. Recombination offers evolutionary advantages including increased efficiency of viral replication and translation. However, this study found no differences in disease severity between recombinant and non-recombinant strains.

There are several limitations in this study. The results from this study found relatively lower prevalence of RV in stools compared to other reports, most of which were from countries with temperate climate. It is possible that the semi-nested PCR used may be less sensitive than real-time PCR under certain conditions [Savolainen-Kopra et al., 2013]. Even so, samples such as nasopharyngeal swabs, tracheal, and nasal aspirates from patients with respiratory symptoms are likely to result in more frequent RV-positive finding. Furthermore, comparison between the acute gastroenteritis and the HFMD/herpangina cohorts in this study was limited by the low RV prevalence, unmatched number of samples, age, and disease seasonality. Nevertheless, accumulating reports of RV detection in fecal samples from individuals with diarrhea will require further validation, but may potentially reveal a new etiologic role for RV-related gastrointestinal diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the entire staff of the Center of Excellence in Clinical Virology, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, who made this study possible.