Toward a simple risk assessment screening tool for HCV infection in Egypt

Abstract

Asymptomatic patients with HCV infection identified through screening program could benefit not only from treatment but also from other interventions such as counseling to maintain health and avoid risk behaviors. This might prevent the spread of infection and result in significant public health benefits. However, mass screening would quickly deplete resources. This work aims to develop a brief HCV risk assessment questionnaire that inquires initially about a wide range of risk factors found to be potentially associated with HCV infection in order to identify the few most significant questions that could be quickly used to facilitate cost-effective HCV case-finding in the general population in Egypt. An exhaustive literature search was done to include all reported HCV risk factors that were pooled in a 65 item questionnaire. After an initial pilot study, a case-control study was performed that included 1,024 cases and 1,046 controls. In a multivariable model, a list of independent risk factors were found to be significant predictors for being HCV seropositive among two age strata (<45 and >45 years) for each gender. A simplified model that assigned values of the odds ratio as a weight for each factor present predicted HCV infection with high diagnostic accuracy. Attaining the defined cut-off value of the total risk score enhances the effectiveness of screening. HCV risk factors in the Egyptian population vary by age and gender. An accurate prediction screening tool can be used to identify those at high risk who may benefit most from HCV serologic testing. These results are to be further validated in a large scale cross-sectional study to assess the wider use of this tool. J. Med. Virol. 88:1767–1775, 2016. © 2016 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Abbreviations

-

- CI

-

- confidence interval

-

- ELISA

-

- enzyme linked immunosorbant assay

-

- HBV

-

- hepatitis B virus

-

- HCV

-

- hepatitis C virus

-

- HIV

-

- human immunodeficiency virus

-

- OR

-

- odds ratio

-

- PAT

-

- parenteral anti-schistosomal treatment

-

- PCR

-

- polymerase chain reaction

-

- PIVDs

-

- persons injecting intravenous drug

-

- STIs

-

- sexually transmitted infections

BACKGROUND

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is one of the most common blood-borne pathogens affecting an estimated 170 million individuals worldwide [Lavanchy, 2009; Gower et al., 2014]. Almost 75% of HCV infections become chronic. Because patients are usually asymptomatic from the onset of infection until the development of cirrhosis, many individuals are unaware of their infection status and remain undetected for decades [Bellentani et al., 1999; Cales et al., 2010; Nguyen and Nguyen, 2013]. HCV is emerging as an important public health problem in developing countries [Kandeel et al., 2012]. Egypt has a devastating seroprevalence of HCV ranging from 6% to 20% in the general population. The relatively high ongoing HCV transmission rates is a challenge; it is projected that up to 416,000 infections may occur each year in Egypt [Kandeel et al., 2012]. A recent mathematical HCV model assumed that and that each HCV patient can transmit the infection to 3.54 subjects suggesting a self-sustained spread [Breban et al., 2014].

Due to the absence of a vaccine and high cost and limited availability of medical therapy, primary prevention of HCV infection remains the most important strategy to prevent HCV complications [Kandeel et al., 2012]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends testing in the United States for persons with risk factors, and those in the age group with highest US prevalence, those born between 1945 and 1965 [Smith et al., 2012]. Egypt like other countries with a similarly high HCV disease burden, has limited funds to support wide-scale prevention programs. Therefore, targeting and prioritizing prevention activities are essential [Artenie et al., 2014]. A critical step is the ability to identify as many undiagnosed HCV-infected individuals as possible in the general population before the development of important clinical sequalae of long term chronic liver disease [Lavanchy, 2009]. Identified asymptomatic patients with HCV could benefit from counseling on avoiding high risk behaviors that might help self-protection and prevent further spread of HCV in the community [U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2013].

Available measures of behavioral risks for drug injection such as HIV Risk Behavior Scale [Darke et al., 1991] and the Injecting Risk Questionnaire [Stimson et al., 1998] have poor content validity for HCV monitoring purposes due to insufficient coverage of the full range of HCV risk practices implicated by the plausibility of environmental contamination. The standardized Blood-Borne Virus-Transmission Risk Assessment Questionnaire (BBV-TRAQ) [Fry et al., 1998] was used to enable comprehensive assessment of injecting and other behavioral risk practices for HCV, HBV, and HIV among high risk groups such as persons who inject drugs (PWID). Previous case-finding efforts have concentrated on high-risk groups or volunteer blood donors [Murphy et al., 1996; Lapane et al., 1998]. In community practice, targeting screening toward healthy people at higher risk for infection is of great public health impact [Rocca et al., 2004].

Studies that adequately assess the usefulness of risk factor assessment to guide selective screening strategies in the general population are essentially needed. Considering that HCV risk factors may differ from country to country, the present study was accordingly designed aiming to encompass a wide range of risk factors found to be potentially associated with HCV infection, in order to identify the few most significant questions that could be quickly used to facilitate cost-effective HCV case-finding in the general population in Egypt.

METHODS

For this case-control study, an initial systematic review was performed searching electronic databases and grey literature (1989–2013) with keywords (HCV + Risk + Factor) or (HCV + epidemiology + Egypt) as described earlier by our research group [El-Ghitany et al., 2015]. This resulted in 1,368 relevant articles. All risk factors for HCV positivity found in those articles were included in a questionnaire (65 risk factor headings).

Sample Size and Data Collection

A minimum sample of 664 (332 patients and 332 controls) was required to have an 80% power of detecting an increase of 1.5 times risk as significant at the 5% level (using G*power 3.1.9.2 software). Exclusion criteria were for the cases HBV or HIV seropositivity based on a previous documented history of these infections. Exclusion criteria were for the controls were HCV seropositivity based on HCV antibody testing done for all enrolled controls.

The study was conducted during the 6-month period between 31 January and 31 August 2013 and included all patients who visited the outpatient clinics of two major hospitals in Alexandria where patients with chronic HCV infection are referred to from surrounding governorates to receive interferon therapy. Meanwhile, a sample of sex and age-group matched controls were enrolled through campaigns that offered free investigations of HCV after completing the questionnaire (109 of them tested positive for HCV and were added to cases). Age and gender matching of the controls was considered through sampling. The enrollment period was extended till 11/10/2013 to complete the control sample. The study population comprised 729 females (355 cases, 374 controls) and 1,341 males (669 cases, 672 controls).

Face-to-face interviews were conducted by six trained recruiters. The questionnaire was tested through a pilot study of 10 participants who were not included in the analyses. Each data-sheet was completed in 15–20 min.

Laboratory Investigation

A 5 ml venous blood sample was drawn from each participant and collected into a clean, dry vacutainer tube without an anticoagulant. Samples were allowed to clot naturally and completely. Sera were separated by centrifugation at room temperature at 1,000g for 5 min. Aliquots were stored at −20 for further analysis. Serologic evidence of HCV infection by detecting HCV antibodies in serum was done using a commercial Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (3rd generation ELISA kits; DIALAB®, Austria). A second serum sample was retested by another ELISA kit (DiaSorin Murex®, version 4.0, Italy) for confirmation.

Statistical Analysis

Bivariate analyses

After data collection, data sheets were revised, coded and entered into statistical software SPSS IBM version 20. All statistical analysis was done using two tailed tests and an alpha error of 0.05. Stratified analyses were perfomed for males aged less than 45 years versus 45 or greater years, and for females in the same age groups Descriptive statistics in the form of frequencies and percent were used to describe the occurrence of the different categories of the studied risk factors among cases and controls. Pearson chi-square tests were used to test for association between the studied risk factors and HCV positive status. All exposures were tested for association with anti-HCV positivity in bivariate analysis for two age strata (<45 and >45 years) for both males and females.

Multivariate stepwise logistic regression

The significant factors in bivariate analysis were analyzed using backward stepwise multivariate logistic regression. Whenever a risk factor was significantly associated with HCV positive status, it was included in the assessment form. Selection of independent predictors for inclusion in the HCV risk score was based on their relative prognostic contribution in the full logistic regression model. Variables were ranked by their magnitude of risk (odds ratio), and those without significant contribution were sequentially removed from the model until all variables reached statistical significance in the full multivariate model (evaluated as a ratio of the global χ2 statistic from the reduced compared with full model). For each patient, the HCV risk score was calculated as the simple arithmetic sum of the nearest integral value assigned to each risk factor based on the multivariate-adjusted risk relationship.

Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis

The discriminatory capacity of the risk score was assessed by using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (c statistic) as an index of model performance. The c statistic reflects the concordance of predictions with actual outcomes in rank order, with a c statistic of 1.0 indicating perfect discrimination. The reliability of risk score prediction was also evaluated by comparing the observed HCV status with those predicted by the risk score across deciles of risk established by dividing patients according to predicted status from the multivariate model and then determining the actual morbidity for each group.

RESULTS

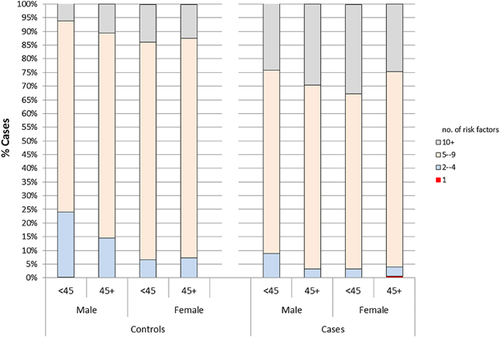

The study comprised 1024 HCV cases and 1046 controls. Almost half of the participants (48.4%) were between 35 to <50 years of age, 26.8% were aged <35 years and 24.8% aged 50 years or more. Male participants constituted 64.8% of the sample. Other socio-demographic characteristics are described in (Table I). At least one and often multiple risk factors were encountered among each case or control (P = 0.001) (Fig. 1). Most exposures were strongly associated with HCV seropositivity in age and gender adjusted bivariate analyses. Details on community acquired, behavioral, iatrogenic and health related risk factors associated with HCV positivity are displayed in (Suppl. Tables SI–IV).

| Control | Cases | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (n = 1,046) | % | No. (n = 1,024) | % | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| <35 | 294 | 28.1 | 261 | 25.5 |

| 35–<50 | 509 | 48.7 | 492 | 48.0 |

| 50+ | 243 | 23.2 | 271 | 26.5 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 672 | 64.2 | 669 | 65.3 |

| Female | 374 | 35.8 | 355 | 34.7 |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 905 | 86.5 | 389 | 38.1 |

| Rural | 141 | 13.5 | 633 | 61.9 |

| OR [95%CI] | 10.444 [8.4–12.986] | |||

| Education | ||||

| Illiteratea | 201 | 19.2 | 371 | 36.3 |

| Literate; educational level | ||||

| Primary | 168 | 16.1 | 133 | 13.0 |

| Preparatory | 97 | 9.3 | 79 | 7.7 |

| Secondary | 388 | 37.1 | 304 | 29.8 |

| University | 192 | 18.4 | 132 | 12.9 |

| Post graduate | 2 | 0.2 | ||

| OR,[95%CI (illiterate vs. literateb) | 2.388 [1.956–2.917] | |||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 183 | 17.5 | 110 | 10.8 |

| Marrieda | 764 | 73.1 | 840 | 82.2 |

| Divorced | 21 | 2.0 | 10 | 1.0 |

| Widow/widower | 77 | 7.4 | 62 | 6.1 |

| OR [95%CI (married vs not marriedb) | 1.829 [1.416–2.363] | |||

| Family size | ||||

| Family 5 or less | 898 | 86.1 | 662 | 65.0 |

| Family more than 5 | 145 | 13.9 | 356 | 35.0 |

| OR [95%CI] | 3.33 [2.679–4.14] | |||

| Occupation | ||||

| Unemployeda | 243 | 23.2 | 336 | 32.8 |

| Healthcare | 59 | 5.6 | 14 | 1.4 |

| Fisherman | 4 | 0.4 | 9 | 0.9 |

| Clerk | 290 | 27.7 | 146 | 14.3 |

| Manual work | 127 | 12.1 | 146 | 14.3 |

| Butcher | 4 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Grocer | 1 | 0.1 | 6 | 0.6 |

| Driver | 63 | 6.0 | 40 | 3.9 |

| Collects hospital wastes | 2 | 0.2 | ||

| Waste worker | 43 | 4.1 | 13 | 1.3 |

| Farmera | 16 | 1.5 | 153 | 14.9 |

| OR [95%CI] (not working vs. workingb) | 1.614 [1.329–1.959] | |||

| OR [95%CI (farmer vs. other occupationsb) | 1.203 [0.932–1.553] | |||

| Total | 1,046 | 100.0 | 1,024 | 100.0 |

- a Significant difference between cases and controls by z test of proportion at 95%CI.

- b Reference category.

The multiple logistic regression model (Table II) displays all independent risk factors for having HCV infection. The table lists the factors found to be significant predictors for being HCV seropositive among the two age strata (<45 and >45 yrs.) for both males and females keeping all other factors constant. The magnitude of effect for all predictors ranged from a 2- to 18-fold increase in risk. The weights of the identified risk factors (OR) were ranked according to the magnitude of effect with an overall score represented by the total.

| 95%CI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Sig. | Exp (B) | LL | UL | Risk score (OR) | |

| Male <45 yrs | ||||||

| Blood/blood products transfusion | 2.171 | 0.000 | 8.768 | 3.673 | 20.934 | 9 |

| Rural residence | 2.042 | 0.000 | 7.708 | 5.164 | 11.507 | 8 |

| Fatigue | 1.906 | 0.000 | 6.729 | 3.916 | 11.564 | 7 |

| History of jaundice | 1.735 | 0.000 | 5.671 | 2.683 | 11.987 | 6 |

| History of PAT | 0.913 | 0.004 | 2.493 | 1.333 | 4.662 | 2 |

| Incarceration | 0.898 | 0.001 | 2.455 | 1.472 | 4.094 | 2 |

| Unsafe rout of sexa | 0.778 | 0.051 | 2.177 | 0.99 | 5.444 | 2 |

| Contact with jaundice patient | 0.769 | 0.002 | 2.158 | 1.323 | 3.519 | 2 |

| Use of barber toolsb | 0.679 | 0.012 | 1.971 | 1.164 | 3.339 | 2 |

| Substance abuse | 0.659 | 0.014 | 1.933 | 1.142 | 3.271 | 2 |

| Living abroad | 0.563 | 0.009 | 1.756 | 1.154 | 2.672 | 2 |

| Hospitalization | 0.56 | 0.006 | 1.75 | 1.179 | 2.598 | 2 |

| Needle prick | 0.542 | 0.042 | 1.72 | 1.019 | 2.904 | 2 |

| Constant | −5.105- | 0.000 | 0.006 | 47∼ | ||

| Male >45 yrs | ||||||

| Rural residence | 2.722 | 0.000 | 15.204 | 8.189 | 28.229 | 15 |

| Blood/blood products transfusion | 2.101 | 0.001 | 8.81 | 5.452 | 12.452 | 8 |

| Incarceration | 1.378 | 0.042 | 3.966 | 1.054 | 14.925 | 4 |

| Substance abuse | 1.156 | 0.047 | 3.176 | 0.924 | 10.922 | 3 |

| History of PAT | 1.049 | 0.001 | 2.854 | 1.502 | 5.421 | 3 |

| History of jaundice | 1.005 | 0.009 | 2.732 | 1.279 | 5.836 | 3 |

| Fatigue | 0.823 | 0.003 | 2.277 | 1.324 | 3.915 | 2 |

| Needle prick | 0.79 | 0.029 | 2.204 | 1.083 | 4.483 | 2 |

| Living abroad | 0.5 | 0.056 | 1.65 | 0.987 | 2.756 | 2 |

| History of invasive procedures | 0.499 | 0.048 | 1.648 | 1.005 | 2.703 | 2 |

| Constant | −26.153- | 0.999 | 0 | 44∼ | ||

| Female <45 yrs | ||||||

| Rural residence | 2.869 | 0.000 | 17.621 | 7.284 | 42.63 | 18 |

| History of PAT | 2.195 | 0.000 | 8.979 | 3.034 | 26.572 | 9 |

| History of jaundice | 1.476 | 0.033 | 4.374 | 1.125 | 17.003 | 4 |

| Menses during intercourse | 1.473 | 0.070 | 4.364 | 0.888 | 21.45 | 4 |

| Blood/blood products transfusion | 1.38 | 0.008 | 3.974 | 1.43 | 11.042 | 4 |

| Hospitalization | 1.2 | 0.005 | 3.322 | 1.445 | 7.634 | 3 |

| Fatigue | 1.2 | 0.004 | 3.3 | 1.85 | 6.2 | 3 |

| History of invasive procedures | 1.119 | 0.005 | 3.063 | 1.4 | 6.698 | 3 |

| Blood sample | 0.729 | 0.002 | 2 | 1.1 | 4.9 | 2 |

| Constant | −24.270- | 0.999 | 0 | 51∼ | ||

| Female >45 yrs | ||||||

| Rural residence | 1.9 | 0.000 | 6.684 | 2.8 | 12.4 | 7 |

| History of PAT | 1.764 | 0.000 | 5.838 | 2.731 | 12.483 | 6 |

| Use of beautician toolsc | 1.113 | 0.000 | 3.044 | 1.68 | 5.515 | 3 |

| Labour and delivery at home | 0.814 | 0.007 | 2.256 | 1.246 | 4.084 | 2 |

| Needle prick | 0.764 | 0.037 | 2.147 | 1.046 | 4.408 | 2 |

| Fatigue | 0.724 | 0.014 | 2.063 | 1.158 | 3.677 | 2 |

| Blood/blood products transfusion | 0.621 | 0.073 | 1.862 | 0.943 | 3.674 | 2 |

| History of jaundice | 0.17 | 0.025 | 1.2 | 1.004 | 8.45 | 1 |

| Constant | −5.160- | 0.000 | 0.006 | 25∼ | ||

- PAT, parenteral anti-schistosomiasis therapy; ∼, total score.

- a This include anal intercourse, and oral sex, sex during menses.

- b Shaving at barber shops using its shaving sets.

- c Body care at beauty centres using its sets.

After scoring for each included variable, the total score was calculated and ROC curve analysis was used to estimate the most valid discriminating cutoff point between persons with anti-HCV negative and anti-HCV positive status targeting the point of the highest sensitivity and specificity considering area under curve as a measure for discrimination ability (Figs. 1 and 2). Table II shows that the best recorded cut off point for males aged <45 years is 11; scores ≥11 were associated with HCV positive status with sensitivity and specificity of 70% and 90%, respectively and a recorded area under curve (AUC) of 0.86; P < 0.001. Regarding males above 45 years, the most fit cutoff point was eight with sensitivity and specificity of 70% and 80%, respectively and AUC of 0.85; P < 0.001. For females aged less than 45 years, the best recorded cutoff point for anti-HCV status was 11 with sensitivity and specificity of 80% and 90%, respectively and AUC of 0.89; P < 0.01. For females aged 45 years or more, seven points or more was found to be the most discriminating value with sensitivity and specificity of 75% and 88%, respectively and AUC of 0.87; P < 0.001 (Fig. 2).

DISCUSSION

Numerous epidemiologic studies all over the world have reported diverse exposures associated with HCV infection. Risk factors in Egypt may differ substantially from those in other countries, given the devastatingly high prevalence of HCV infection in Egypt [Lavanchy, 2009; Mohamoud et al., 2013]. Our overall results confirm that at least one and often multiple risk factors may be identified in each HCV patient. This is in contrast to findings in other countries where 40% of HCV infected patients have no apparent source of infection [Alter et al., 1990].

The high burden of HCV in Egypt necessitates the identification of past and current risk factors for infection in order to properly focus intervention strategies. Epidemiological studies in Egypt showed that age and gender were highly associated with HCV infection [Habib et al., 2001; Medhat et al., 2002; Guerra et al., 2012; Mohamoud et al., 2013; El-Ghitany et al., 2015]. Thus, stratifying our subjects by both gender and age provides an insight into modes of HCV transmission that may differ between males and females and age groups.

Guided by the results of the pilot study, we developed a risk assessment questionnaire that inquires about a list of independent factors found to be significantly associated with HCV seropositvity after age and gender stratification. The number of risk items varied between strata and comprised 8–13 questions. The questionnaire stratifies patients into four HCV risk groups to help target HCV screening of asymptomatic populations. Each item has a score that represents its weight and simply totaling the number of “positive” responses assigning a risk score for an individual. The high predictive value and statistical accuracy of the proposed instrument supports that a negative result (below the cut-off point) on risk assessment can eliminate the need for HCV serologic testing in the majority of a population being assessed among persons without signs or symptoms of liver disease.

We propose a simplified HCV risk assessment model that would be an appealing instrument to clinicians who need to perform HCV serological testing for their patients. It could be also the first step in general population screening, with antibody testing recommended only for asymptomatic individuals with positive results (above the cut-off point).

The significant exposures common to both gender and both age groups included rural residence, parenteral anti-schistosomiasis therapy (PAT), blood transfusion, history of jaundice, and unexplained fatigue.

In agreement with several Egyptian studies [Mohamoud et al., 2013; Zamani et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2013; El-Ghitany et al., 2015], rural residence was highly associated with HCV infection in our data, with more than 10 fold higher risk comparing to urban residence. According to our data, being a rural resident in Egypt should indicate screening for all groups except males <45 years. This reflects in part the interplay of several closely related co-factors existing in rural communities including illiteracy, large family size, high prevalence of schistosomal infection with prior administration of PAT, quackery and folk medicine, and inadequate health care with laxity in sterilization techniques [Habib et al., 2001; Medhat et al., 2002; El-Ghitany et al., 2015].

PAT has frequently been identified as a risk factor for HCV infection among older Egyptians [Frank et al., 2000; Mohamoud et al., 2013; El-Ghitany et al., 2015], as in our study. Because PAT was replaced with oral anti-schistosomiasis therapy in 1982, it is difficult to explain the report of this risk among a small number of persons (n = 555; 26.8%) under age 35. It is possible that some participants particularly those who are illiterate, may have no official birth registration and not be aware of their current age. It is also possible that this may be attributed to recall bias or misunderstanding of the question.

In developed countries, the risk of transmission through blood transfusion has greatly diminished with the introduction of effective routine screening in blood banks [Wasley and Alter, 2000]. However, it remains a significant past and a potential current risk in developing countries due to limited screening procedures. In a recent meta-analysis comparing HCV risk factors worldwide and in Egypt, El-Ghitany et al. [2015] found that the risk for acquiring HCV through blood/blood product transfusion is decreasing over decades. In the present study, blood transfusion has been decreasing over recent decades [El-Ghitany et al., 2015]. However, in our study blood transfusion was still an independent predictor of anti-HCV in both the old and younger population. This agrees with results of a similar community-based study that used lower age cutoff in stratifying the young population (<30 years) [Medhat et al., 2002] suggesting that anti-HCV testing in blood banks is not totally reliable or that some participants were confused blood transfusion with blood donation.

Fatigue is the most frequent symptom in HCV. Some studies have shown women are less likely to report fatigue than men [Wust et al., 2008]. Nevertheless, having fatigue was associated with increased risk of HCV seropositivity among both men and women in our study population.

The risk of HCV transmission by accidental needle-stick injury has raised a considerable concern in the present model. This risk was encountered in both age groups among men and in women >45 years. Needle stick injury is common among health care workers, tattoo artist, barbers, solid waste workers, informal injectionists, and family members [Abd El-Wahab et al., 2014; Tarigan et al., 2015]. Discarded needles act as a vector for virus transmission since the viral load was found decreases by less than one log upon their storing for 24 [Haber et al., 2007]. Moreover, Haber et al. [2007] stated that all cases of needle stick injury should be promptly investigated by HCV-PCR as seroconversion is more likely to occur.

Analysis of exposures by gender did reveal some behavioral and community-acquired risks exclusive to male respondents including incarceration, living abroad, and IVDUs. Unsafe sex and ever contact with a jaundiced patient were found to be a risk only among younger males. These practices may be more prevalent among men lacking family network or social support which may lead to sharing of personal care and hygiene objects, engagement in problematic drug use and high risk sexual activities [Mir-Nasseri et al., 2011; Ataei et al., 2012]. This difference by gender may be a reflection of the conservative society which prohibits such practices among women [Mir-Nasseri et al., 2011].

Antenatal care and childbirth may necessitate instrumentation, injections, and incidental blood transfusion. Unsterilized tools used during the delivery of a child may increase the risk of HCV transmission. In agreement with Murphy et al. [2010], both doctor/midwife assisted at home labor and delivery were associated with HCV infection among the older female population, likely due to iatrogenic exposure. In Egypt, normal labor theatre has less adequate infection control and little-adherence to universal precautions [Khan et al., 2008].

Similar methods have been used to develop brief HCV questionnaires in other countries albeit with somewhat lower sensitivity and specificity [Nguyen et al., 2005; McGinn et al., 2008].

A brief hepatitis C virus risk assessment instrument would be appealing to clinicians who need an estimate of infection prevalence in their patients to assess individual risk. The proposed tool could be used as a self-administered questionnaire or face to face interview for persons who are illiterate, although the lack of anonymity might inhibit interview responses to sensitive questions.

A potential limitation to screening on the basis of such tool is the difficulty in obtaining accurate histories of certain key risky practices like intravenous drug use or high-risk sexual behaviors. Physicians may hesitate to ask patients about, or patients may decline to disclose these. Ultimately, patients could assess their own HCV risk. Self-identification, if widely practiced, could be an effective method of case ascertainment. Targets will be patients seeking medical advice in health care setting for any reason. Other possible settings would be schools, institutions or rural outreach screening programs serving populations at high risk for HCV infection.

After validation of our proposed model in the coming phase, an electronic version of the questionnaire (EGCRISC) enabled with a calculator for calculating the risk score and to assess the risk will be available through the internet portal www.virus-c.com. This tool will enable HCV case finding in Egypt by encouraging people to check their risk status and seek diagnosis.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

Inquiry into the patient's sexual history helps to identify appreciable number of possible high risk activities for HCV transmission. However, in our study, reservation about this taboo issue has limited the history taking. Respondents were uncomfortable discussing these factors and only few have disclosed practices of commercial sex, homosexuality and sexual promiscuity in terms of oral or anal sex. Nevertheless, the risk of HCV sexual transmission has never been recognized in any study conducted in Egypt. Likewise, the percentage of patients reporting substance abuse (8.7%) is considerably low comparing to prior reports (23%) [Kandeel et al., 2012] or in developed countries. Withholding this history by the participants may have contributed to an underestimation in the present setting.

Another limitation of our study is that its findings are from persons in Alexandria and surrounding areas. To ascertain whether these results are generalizable to other regions, this study will be continued for a second phase. A large scale cross-sectional study will be conducted in a representative proportionally allocated sample of the Egyptian population to test a population with unknown HCV status for further validation of the screening tools among the two age strata in both genders. Individuals attaining a total score above the defined cut-off point will be recommended for HCV testing. Perspective screening could allow more frequent and effective treatment of the infection [Alter et al., 2004].

CONCLUSION

We found that risk factors for chronic HCV infection in Egyptian patients differ by gender and age group. Nevertheless, common factors for all groups include rural residence, history of blood\blood products transfusion, receiving PAT, history of jaundice and fatigue. We developed a sensitive and specific simple risk factors-based screening tool with eight to 13 binary questions. Each positive answer has an odds ratio-dependent weighed score. When the total score exceeds the cutoff point, HCV testing should be recommended. Our next step would be validation of this tool.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board and the ethics committee of the High Institute of Public Health affiliated to Alexandria University, Egypt. The research was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. All participants were invited to sign an informed written consent form after receiving explanation of the aims and concerns of the study. Data sheets were coded and manipulated to ensure anonymity and confidentiality of participants' data.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported financially by the Science and Technology Development Fund (STDF), Egypt; Project No. 3469.