Protease inhibitor resistance mutations in untreated Brazilian patients infected with HCV: Novel insights about targeted genotyping approaches

Abstract

Several new direct-acting antiviral (DAA) drugs are being developed or are already approved for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. HCV variants presenting drug-resistant phenotypes were observed both in vitro and during clinical trials. The aim of this study was to characterize amino acid changes at positions previously associated with resistance in the NS3 protease in untreated Brazilian patients infected with HCV genotypes 1a and 1b. Plasma samples from 171 untreated Brazilian patients infected with HCV were obtained from the Department of Gastroenterology of Clinics Hospital (HCFMUSP) in São Paulo, Brazil. Nested PCR and Sanger sequencing were used to obtain genetic information on the NS3 protein. Bioinformatics was used to confirm subtype information and analyze frequencies of resistance mutations. The results from the genotype analysis using non-NS3 targeted methods were at variance with those obtained from the NS3 protease phylogenetic analyses. It was found that 7.4% of patients infected with HCV genotype 1a showed the resistance-associated mutations V36L, T54S, Q80K, and R155K, while 5.1% of patients infected with HCV genotype 1b had the resistance-associated mutations V36L, Q41R, T54S, and D168S. Notably, codons at positions 80 and 155 differed between samples from Brazilian patient used in this study and global isolates. The present study demonstrates that genotyping methods targeting the NS3 protein showed a difference of results when compared to mainstream methodologies (INNO-LiPA and polymerase sequencing). The resistance mutations present in untreated patients infected with HCV and codon composition bias by geographical location warrant closer examination. J. Med. Virol. 86: 1714–1721, 2014. © 2014 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

The large number of individuals infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) around the world is a major public health problem. Approximately 3% of the world population are infected [Pybus et al., 2001], and several aspects such as an asymptomatic acute phase [Farci et al., 2000] and low rates of sustained virologic response highlight the severity of the HCV epidemic. The standard treatment of pegylated interferon (PEG-INF) plus Ribavirin produces sustained virologic response in approximately 40–50% of patients infected with HCV genotype 1 and about 80% of patients infected with genotypes 2 and 3 [Manns et al., 2001; Hadziyannis et al., 2004]. In addition to sub-optimal sustained virological response, this approach produces side effects associated with treatment dropout in a significant proportion of patients [Kowdley, 2005]. New drugs targeting essential viral replication factors were designed to decrease side effects and improve sustained virological response rates. Collectively referred to as direct acting antivirals (DAAs), these drugs inhibit directly the serine protease NS3 and the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase NS5B. Other targeted drugs, such as NS5A and P7 inhibitors, are still in development [Gao et al., 2010; Vermehren and Sarrazin, 2011].

Two new inhibitors, Telaprevir and Boceprevir, were recently approved for the treatment of hepatitis C genotype 1 [Poordad et al., 2011; Liapakis and Jacobson, 2012]. Other protease inhibitors such BI201335, TMC-435, mericitabine (RG7128), and Filibuvir showed promising results in recent clinical trials [Le Pogam et al., 2010; Lenz et al., 2010; Lemke et al., 2011]. The sustained virological response rate for triple therapy using PEG-INF plus Ribavirin and protease inhibitors (Telaprevir or Boceprevir) was greater than 70% in one population that was studied [Chary and Holodniy, 2010].

HCV is classified phylogenetically into seven genotypes with several subtypes (1a, 1b, 2a, etc.) due to high mutation rates [Simmonds et al., 2005; Gottwein et al., 2009]. As stated earlier, the PEG-INF plus Ribavirin sustained virological response rate is genotype-dependent [Qureshi et al., 2009]. The action of first-generation protease inhibitors is also genotype-dependent, primarily targeting genotype 1. In addition, different drug response profiles are observed between subtypes within the same genotype [Thibeault et al., 2004; Cento et al., 2012].

The emergence of drug-resistant strains of HCV has resulted in the failure of many therapeutic strategies [Tong et al., 2008]. Such strains have been observed in in vitro assays as well as in clinical trials [Flint et al., 2009; McCown et al., 2009; Susser et al., 2009]. The NS3 mutations R155K and A156T were reported as high resistance mutations [Courcambeck et al., 2006]. Other NS3 mutations, however, have been associated with lower resistance levels [Welsch et al., 2008]. Thus, combined drug schedules are currently being used to treat HCV infection to counter the possibility of monotherapy failure due to the appearance of resistant variants [Thompson and McHutchison, 2009].

The presence of drug resistance-associated mutations in HCV, albeit at low frequencies, raises public health concerns. These mutations have been observed in several distinct isolates collected worldwide [Bartels et al., 2008; Bae et al., 2010]. Sanger sequencing underestimated resistance mutation frequency in a HCV quasispecies population, making an accurate assessment of prevalence difficult [Ninomiya et al., 2012]. High throughput methods revealed the existence of strains with low mutation frequency among quasispecies [Beerenwinkel and Zagordi, 2011]; however, the role of these strains in drug treatment failure remains poorly understood [Macalalad et al., 2012].

The objectives of this study were to characterize HCV subtypes by phylogenetic analysis of the NS3 protease sequence in samples from chronically HCV-infected untreated patients with protease inhibitors, in Brazil, and to assess resistance-associated mutation profiles for NS3 by targeted genotyping techniques.

METHODS

Samples

Plasma samples of 171 identified previously HCV 1a- and 1b-infected patients were obtained from the Department of Gastroenterology of Clinics Hospital (HCFMUSP; São Paulo, Brazil). The genotyping methodology targeted regions other than the NS3 regions as INNO-LiPA, 5′ UTR and Polymerase NS5B sequencing (no individual samples information could be acquired about the specific genotyping technique). The signed patient consent forms were approved by the hospital ethics board in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

DNA Extraction

HCV RNA extractions were performed using the QIAamp Viral RNA Kit (Qiagen [Uniscience do Brasil], Sao Paolo, Brazil) from 140 µl of serum, according to manufacturer's recommendations.

RT-PCR and PCR

Reverse transcription reactions were performed with Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, California, EUA) and random primers. The cycling steps for all primer sets were as follows: 65°C for 5 min, 25°C for 5 min, 54°C for 60 min, and 70°C for 15 min.

A two-step (nested) PCR protocol was used for the NS3 gene primer set (P1aF1/P1aR1 and P1bF1/P1bR1 for the first PCR reaction; P1aF2/P1aR2 and P1bF2/P1bR2 for the second reaction) [Peres-da-Silva et al., 2010]. The final volume for the first reaction was 50 µl, as follows: 5 µl 10× PCR buffer (600 mM Tris–SO4, pH 8.9; 180 mM ammonium sulfate); 2 µl primer (20 pmol/µl), 1.0 µl dNTP, 1.5 µl MgSO4, 0.3 µl Platinum Taq High Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Life Technologies), and 10 µl cDNA. The steps of the reaction were as follows: 94°C for 30 sec; 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 sec, 56°C for 30 sec, 68°C for 1 min; final extension at 68°C for 10 min.

The second reaction was performed under the same conditions, using 5 µl of reaction product from the first PCR as the DNA template, with the steps as follows: 94°C for 30 sec; 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, 68°C for 45 sec; final extension at 68°C for 10 min.

Sanger Sequencing

PCR products were purified with illustra GFX PCR Purification Kit (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). Capillary electrophoresis sequencing was performed with ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (PE Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, California, EUA) on an ABI PRISM 3100 automatic sequencer (PE Applied Biosystems) according to manufacturer's instructions. All sequences were recorded in GenBank under the accessions numbers KF011281–KF011451.

Phylogenetic and Resistance-Associated Mutation Analysis

Since samples were genotyped by methods targeting random viral genes, after sequencing, contigs were created with Phred/Phrap/Consed [Ewing and Green, 1998; Ewing et al., 1998; Gordon et al., 1998].

The sample contigs and 16 reference sequences (AF009606_1a, D90208_1b, AY05129_1c, D14853_1c, D00944_2a, D10988_2b, AB047639_2a, D50409_2c, D17763_3a, D49374_3b, D28917_3a, Y11604_4a, Y13184_5a, Y12083_6a, D84262_6b e EF108306_7a) were aligned using MUSCLE [Edgar, 2004]. The best substitution model was identified using ModelTest [Posada and Crandall, 1998]. A phylogenetic tree was estimated from a HKY DNA substitution model with 1,000 bootstrap replicates using Seaview 4.0 [Gouy et al., 2010].

Resistance-associated mutation analysis was performed with BioEdit 7.1.3 [Hall, 1999]. Nucleotide sequences were translated and DAA-resistance mutation frequencies were determined [Lin et al., 2005; Kim and Timm, 2008; Vermehren et al., 2012]. The resistance mutation profiles from the Brazilian patient population were compared to previously determined profiles from the Los Alamos database [Alves et al., 2013]. The amino acid composition for codons 80 and 155 from the Brazilian patient samples was determined. These positions were chosen due to high resistance (for codon 155) and the high mutant frequency observed in other studies of the HCV 1a genotype [Cento et al., 2012; Alves et al., 2013]. The wild-type codon was set as the most frequently represented codon in both populations.

RESULTS

HCV Subtype Classification by Phylogenetic Analysis

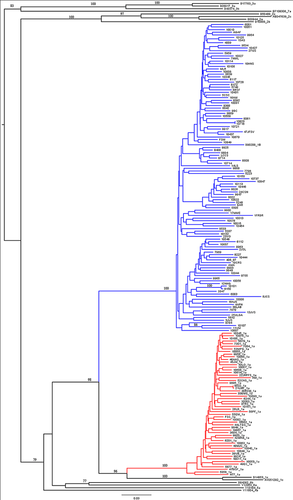

One hundred seventy-one sequences were obtained through Phred/Phrap screening. Previously, genotyping methods targeting other HCV regions as INNO-LiPA, 5′ UTR and Polymerase NS5B sequencing had identified 56 genotype 1a and 115 genotype 1b samples.

Phylogenetic analysis was performed with 16 reference sequences. All samples clustered with genotype 1 as expected; however, some samples were identified as a subtype that was different from what was determined by previous genotyping analyses. Thus, two samples previously classified as subtype 1a clustered with genotype 1b, whereas four samples previously classified as genotype 1b clustered with the 1a genotype. All clusters were statistically significant with a bootstrap value above 90% (Fig. 1).

Identification of Resistance-Associated Mutations

Resistance-associated mutation profiles differed according to genotype. 7.4% (4/54) of genotype 1a patients had the resistance-associated mutations V36L, T54S, Q80K, and R155K, while 5.1% (6/117) of genotype 1b patients had the mutations V36L, Q41R, T54S, and D168S. Among genotype 1a patients, a single mutation was observed in each case, while for genotype 1b, the same mutations were detected on different cases (two T54S and three D168E; Table I).

| Position | Reference strain 1a* | Reference strain 1b** | Resistance mutation | 1a (n = 54) | 1b (n = 117) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36 | V | L | A/M/L/G | V(53) | V(116) |

| L(1) | L(1) | ||||

| 39 | A | A | V | A(54) | A(116) S(1) |

| 41 | Q | Q | R | Q(54) | Q(116) |

| R(1) | |||||

| 43 | F | F | S/C | F (54) | F(117) |

| 54 | T | T | A/S | T (53) | T(115) |

| S(1) | S(2) | ||||

| 80 | Q | Q | K | Q(52) | Q(114) |

| K(1) L(1) | L(3) | ||||

| 109 | R | R | K | R (54) | R(116) |

| S(1) | |||||

| 138 | S | S | T | S (54) | S(117) |

| 155 | R | R | K/T/I/M/G/L/S/K/T/Q | R(53)K(1) | R(117) |

| 156 | A | A | S/T/V/I | A(54) | A(117) |

| 168 | D | D | A/V/E | D(54) | D(114) |

| E(3) | |||||

| 170 | I | I | A | I(53) | I(52) |

| V(1) | V(65) |

- H77* genotype 1a (AF009606) and HPCJCG** genotype 1b (D90208) were the reference sequences. Amino acids in red are associated with protease inhibitor resistance.

The codon composition of resistance-associated mutations was also evaluated. In both subtypes, the V36L and T54S mutations required only one nucleotide substitution at the first position of the wild-type codon, defined as the most frequently observed codon. Q80K (subtype 1a) and Q41R (subtype 1b) also resulted from mutations in the first position of the wild-type codon. In contrast, the R155K (subtype 1a) and D168E (subtype 1b) mutations arose from substitutions as the second and third positions, respectively. The resistance-associated codon R155 had variations at the first and last positions of the wild-type codon sequence (AGA for subtype 1a and CGG for subtype 1b; Table II).

| Subtype | Positions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36 | 39 | 41 | 43 | 54 | 80 | |

| 1a | GTG (50) | GCT (51) | CAG (49) | TTC (51) | ACT (44) | CAA (44) |

| GTA (3) | GCC (3) | CAA (5) | TTT (3) | TCT (1) | CAG (8) | |

| CTG (1) | ACC (9) | CTG (1) | ||||

| AAA (1) | ||||||

| 1b | GTT (74) | GCA (50) | CAA (107) | TTC (113) | ACT (97) | CAA (65) |

| GTC (40) | GCC (3) | CAG (9) | TTT (4) | ACA (8) | CAG (49) | |

| GTA (2) | TCA (1) | CGG (1) | ACC (10) | CTG (2) | ||

| CTC (1) | TCT (2) | CTA (1) | ||||

| Subtype | Positions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 109 | 138 | 155 | 156 | 168 | 170 | |

| 1a | AGG (52) | TCC (51) | AGA (50) | GCC (51) | GAC (53) | ATC (53) |

| AGA (2) | TCT (3) | AGG (2) | GCT (3) | GAT (1) | ATT (1) | |

| CGA (1) | ||||||

| AAA (1) | ||||||

| 1b | AGG (91) | TCT (107) | CGG (93) | GCT (99) | GAC (104) | ATA (52) |

| AGA (24) | TCC (9) | CGA (23) | GCC (17) | GAG (1) | GTA (38) | |

| AGC (1) | TCA (1) | CGC (1) | GCA (1) | GAT (10) | GTG (27) | |

| CGG (1) | GAA (2) | |||||

- Codons in red encode amino acids associated with protease inhibitor resistance.

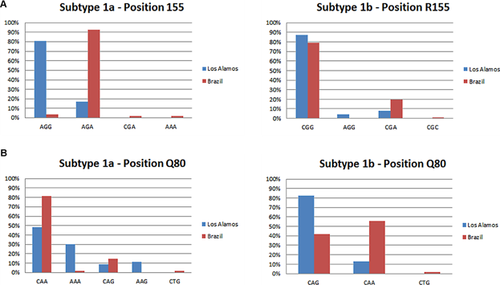

A comparison between sequences from global isolates obtained from the Los Alamos HCV sequence database [Cento et al., 2012] and those from the Brazilian patient samples used in this study revealed a difference in the R155 codon composition. Despite having similar genetic barriers, both required only one substitution to generate a resistance-associated mutation on subtype 1a (Los Alamos: 81.0% AGG; Brazil: 92.5% AGA); two different codons were found in each group. Meanwhile, subtype 1b had a profile similar to the previously reported in silico profile for CGG (Los Alamos: 87.3%; Brazil: 79.4%). The subtype 1b Q80 position was represented by similar frequencies of CAA (55.5%) and CAG (41.8%) in the Brazilian population (Fig. 2).

DISCUSSION

The development of new inhibitor drugs represents a significant advancement in HCV antiviral therapy. Despite the challenge posed by low mutation frequency quasispecies, these targeted drugs provide insights into the impact of resistant variants on viral replicative dynamics and the effects of protein mutations on sustained virological response and other treatment parameters. Clinical trials have already begun to elucidate the role of resistance mutations in treatment failure. These studies also provide a valuable means for determining mutation profiles associated with a particular drug based on in vivo and in vitro trials [Kim and Timm, 2008; Lenz et al., 2010; Fonseca-Coronado et al., 2012; Vermehren et al., 2012].

Effective genotyping methodologies would increase the useful information acquired from clinical trials. This study showed that genotyping methods that use other regions of the HCV genome resulted in the identification of genotypes differing from those obtained through the phylogenetic analysis of the drug target region of the NS3 protein [Larrat et al., 2013]. The six samples showing discordance between genotyping techniques were previously characterized with hepatitis C virus genotype assay (LiPA) 2.0 [Verbeeck et al., 2008]. This assay targets sequence information from 5′ UTR and core region. The genotyping based on 5′ UTR presents several limitations in differentiates 1b and 1a genotype [Chen and Weck, 2002]. Therefore, this discordance could be explained due this genotyping methodology limitation.

The classification of HCV genotypes based on mutation analysis is especially important in light of DAA resistance mutations in untreated patients infected, which raise concerns about the prognosis of these individuals [Bae et al., 2010; Peres-da-Silva et al., 2010; Fonseca-Coronado et al., 2012]. The high mutation rate of HCV is a likely explanation for the geographical bias and significant genetic differences observed within a subtype. This study has shown that the Q80 position is conserved and highly prevalent in the Brazilian population, compared to a previously characterized wild-type HCV on worldwide isolates [Cento et al., 2012]. The Q80K mutation (genotype 1a) had a frequency of 25–35% in global isolates [Paolucci et al., 2012], and of 1.8% in Brazilian patient samples. Despite the few subtype 1a samples from this work, this difference was already reported in previous studies [Peres-da-Silva et al., 2010; Hoffmann et al., 2013; Lampe et al., 2013]. Low frequency strains are not detected by conventional sequencing method, thus leading to an underestimate of their significance in the development of resistance in HCV. The role of low resistance-associated mutation frequency in quasispecies remains poorly understood. New deep sequencing technologies with high throughput may be better suited to the detection of low frequency strains.

Low frequency mutations in quasispecies are nonetheless relevant to the emergence of drug-resistance in HCV, because high virion production increases the frequency of the variant in the population. The identification of high resistance strains such as a subtype 1a strain harboring a R155K mutation, though present at a low frequency (1.8%) raises questions about the actual mutation profile of the population.

The variation at codon 155 has been associated with specific effects on resistance in HCV. Several in vitro studies have correlated this amino acid substitution with a reduction in viral fitness; however, one study has demonstrated that the single mutant strain develops high resistance, leading to treatment failure [Shimakami et al., 2011]. Another study examined the relationship between a mutation at this codon and epitope expression, and found that this mutation promotes CD8 T-cell epitope escape [Salloum et al., 2010], providing an explanation for the persistence of HCV 2 years after the cessation of treatment [Colson and Gerolami, 2011].

Codon bias analysis of resistance-associated mutations revealed subtype specificity. Subtype 1a has a lower genetic barrier than subtype 1b to the development of drug resistance, specifically at codon 155. The most frequently occurring codon at this position (i.e., the wild-type codon) according to the Los Alamos sequence database requires only a single base substitution (AGG → AAG) to confer drug resistance through an Arg to Lys mutation. Meanwhile, the subtype 1b wild-type codon CGG, which is present both in Brazilian patient samples and global isolates requires at least two mutations to generate the same mutant codon. A single mutation in codon 155 in subtype 1a from Brazil is also sufficient to confer drug resistance (AGA → AAA). Although there are two possible single base substitutions that can produce a mutant codon 155 (AGG to AAG and AGA to AAA in the Los Alamos and Brazilian populations, respectively), the genetic barrier is similar in these two geographically distinct populations. Finally, Q80K, a mutation associated with intermediate resistance to the drug TMC-435 was shown to occur at a high frequency in DAA untreated subtype 1a-infected patients, although the genetic barrier was similar in both subtypes.

The reasons for the discrepancy between the high-mutation frequency observed in DAA untreated subtype 1a patients worldwide, and the low frequency observed in Brazilian patients remain unclear, given that the wild-type codon profiles are similar for both groups. The only difference between the two populations is that the resistance mutation occurs at a lower frequency in the Brazilian population. The low Q80K mutation frequency observed in our study population could be associated to geographical factors, as previous suggested by Hoffmann et al. [2013] and Peres-da-Silva et al. [2010].

HCV drug resistance studies have primarily focused on amino acid alterations in the NS3 protein. The present study, which examined codon profiles of untreated Brazilian HCV-infected patients in relation to global profiles, has identified geography as an important factor in the development of resistance in distinct populations. New molecular approaches should allow investigations of minority quasispecies populations. Nevertheless, consideration of the geographical characteristics of the major viral populations can contribute to the development of treatment protocols that are tailored to specific patient populations for improved therapy effectiveness.