Hepatitis B virus genotype G: Prevalence and impact in patients co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus†

Financial Disclosure: MKJ—Research Support Roche Pharmaceuticals, TaiMed Biologics, Gilead Sciences, Pfizer Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals. Consulting: Merck Pharmaceuticals. Advisory Board: Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim. WML—Research Support Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck, Roche Pharmaceuticals, Schering Plough Research Institute, Vertex Pharmaceuticals. Consulting: FoldRx Pharma, Facet Biotech, GSK Pharmaceuticals, Gilead Sciences Inc., Merck, Lilly and Novartis.

Abstract

Relatively little is known about the role of hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotype G (HBV/G) in patients co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and HBV. This study examined the prevalence and association of HBV/G to liver fibrosis in co-infected patients. HBV genotypes were determined by direct sequencing of the HBV surface gene or Trugene® HBV 1.0 assay in 133 patients infected with HIV/HBV. Quantitative testing of HBV-DNA, HBeAg, and anti-HBe were performed using the Versant® HBV 3.0 (for DNA) and the ADVIA®Centaur assay. The non-invasive biomarkers Fib-4 and APRI were used to assess fibrosis stage. Genotype A was present in 103/133 (77%) of the cohort, genotype G in 18/133 (14%) with genotypes D in 8/133, (6%), F 2/133 (1.5%), and H 2/133 (1.5%). Genotype G was associated with hepatitis B e antigen-positivity and high HBV-DNA levels. Additionally, HBV/G (OR 8.25, 95% CI 2.3–29.6, P = 0.0012) was associated with advanced fibrosis score using Fib-4, whereas, being black was not (OR 0.19, 95% CI 0.05–0.07, P = 0.01). HBV/G in this population exhibited a different phenotype than expected for pure G genotypes raising the question of recombination or mixed infections. The frequent finding of HBV/G in co-infected patients and its association with more advanced fibrosis, suggests that this genotype leads to more rapid liver disease progression. Further studies are needed to understand why this genotype occurs more frequently and what impact it has on liver disease progression in patients with HBV/HIV. J. Med. Virol. 83:1551–1558, 2011. © 2011 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Hepadnaviridae Orthohepadnavirus hepatitis B virus (HBV) is identified in 5–10% of the population infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) due to similar modes of transmission of the two viruses [Thio, 2009]. Patients with HIV/HBV co-infection have been found to have an increased risk of death from advanced liver disease compared to those infected with either HIV or HBV alone [Thio et al., 2002; Konopnicki et al., 2005]. Although aminotransferase (ALT) levels are lower in patients infected with HIV/HBV compared to those infected with HBV, fibrosis, or cirrhosis of the liver are found paradoxically more commonly in the co-infected group [Colin et al., 1999]. Furthermore, HBV-specific CD8+ T cell responses are impaired in patients infected with HIV and HBV [Chang et al., 2009]. Collectively, the above findings indicate that viral factors may play an important role in the progression of liver disease.

HBV is classified into 10 different genotypes, A–J, based on divergence of >8% in the nucleotide sequence of the complete HBV genome [Livingston et al., 2007]. HBV genotypes have distinct geographical and ethnic distribution. For example, the United States (US) has a high frequency of genotypes A (HBV/A) and D [Chu et al., 2003], which are also found in Africa, Europe, and India. Genotypes B and C are seen more commonly in Asia and in Asian Americans [Hoffmann and Thio, 2007]. Genotype E is a major genotype in sub-Saharan Africa [Suzuki et al., 2005]. Genotype F is the most prevalent in South America [Nakano et al., 2001; Sanchez et al., 2002]. Genotype H has been found in Central America[Arauz-Ruiz et al., 2002]. Genotype I has been reported from Laos and appears to be a distinctly new genotype [Olinger et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2010]. In addition, a provisional designation of genotype J has been made for a distinct genetic variant from genotype B in Japan [Tatematsu et al., 2009]. Clinical and epidemiological data on HBV genotype G (HBV/G) are limited. HBV/G was classified as the seventh genotype in 2000. In a study of eight HBV/G strains from the US, two stop codons in the pre-core region and a 36-base insertion in the core region of the HBV genome were identified [Kato et al., 2002b]. Thus, HBV/G in its pure form is HBeAg-negative [Tanaka et al., 2008]. HBV/G has been reported to exist in immunocompetent patients, but HBV-DNA levels are very low [Chudy et al., 2006; Li et al., 2007]. HBV/G occurs more often as a mixture with other genotypes, or as a recombinant form, where part of the G genome is fused with A, or other genotypes, so that a whole genome is produced from the two sub-genomic species. These mixtures or recombinant forms have been found most frequently in immunocompromised patients (i.e., those patients infected with HBV/HIV) [Sugiyama et al., 2006; Tanaka et al., 2008]. Two recent European reports found a high prevalence of patients infected with HBV/G (12% and 24%) [Zehender et al., 2003; Lacombe et al., 2006] among those infected with HIV/HBV, and one study found patients infected with HBV/G and HIV were at increased risk of liver fibrosis compared to those infected with other HBV genotypes [Stuyver et al., 2000; Lacombe et al., 2006]. The present study characterizes the prevalence and impact of HBV/G on liver fibrosis in a US cohort of patients infected with HIV/HBV in an urban Ryan White clinic.

METHODS

Patients

One hundred thirty three patients infected chronically with HIV/HBV, from whom a serum sample was available, were identified and included in the study. Patients were selected consecutively from two sources. The first group was from a retrospective study of HIV/HBV patients in clinical care from 1998 to 2003 receiving lamivudine, lamivudine and tenofovir, or tenofovir/emtricitabine who had a stored sample from clinical care. The second group was enrolled consecutively from an ongoing HIV/HBV observational study which began in 2003 with stored samples collected if the participant agreed. All patients in the cohort obtained care at the HIV Clinic at Parkland Health and Hospital Systems, the main teaching hospital for UT Southwestern Medical Center (UTSWMC) in Dallas. This study was approved by UT Southwestern's Institutional Review Board. Baseline demographics, alcohol consumption, anti-hepatitis C (HCV), HIV risk factors, CD4 T cell count, HIV viral load, and the most recent liver function tests (LFTs) and complete white blood cell count were obtained by chart review. Pharmacy data were reviewed to determine if the patient had received active HBV therapy during the observation period. Data on specific HIV antiviral therapy were not collected.

HBV Genotyping

From the overall group, a subset of 35 patients had HBV genotypes performed previously utilizing an automated sequencing system, the Trugene® HBV 1.0 assay (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Deerfield, IL), which can detect HBV/A to H based on the surface/polymerase region of the HBV genome. For the remainder, HBV-DNA was extracted from sera and the HBV surface region (nt248–658) was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [Livingston et al., 2007]. The PCR products are purified and sequenced by the Sequencing Core Center at UTSWMC. HBV/A to H was determined using NCBI online genotyping program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/genotyping/formpage.cgi).

Measurements of HBV DNA Titers, Hepatitis B e Antigen (HBeAg), and Anti-HBe

HBV DNA levels were quantitated (n = 133) using Versant® HBV 3.0 [bDNA; Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics; dynamic range: 3–8 log10 copies/ml (c/ml)]. HBeAg and anti-HBe were measured using the ADVIA®Centaur™ (Siemens Medical Solutions, Tarrytown, NY). Quantitation of HBeAg (n = 81) and anti-HBe (n = 79) were measured using the ADVIA®Centaur™ HBeAg and anti-HBe assays provided by Siemens; dynamic range: 0.1–1,000 and 0.05–4.5 (Fig. 1). In brief, ADVIA®Centaur™ HBeAg assay is an antibody sandwich immunoassay. HBeAg if a >1.0 Index Value is obtained these are considered positive for HBeAg. The ADVIA Centaur anti-HBe assay is a similar immunoassay. An anti-HBe result of <0.8 Index Value is considered negative. An anti-HBe Index Value of >1.2 is considered positive and any value in between is indeterminate.

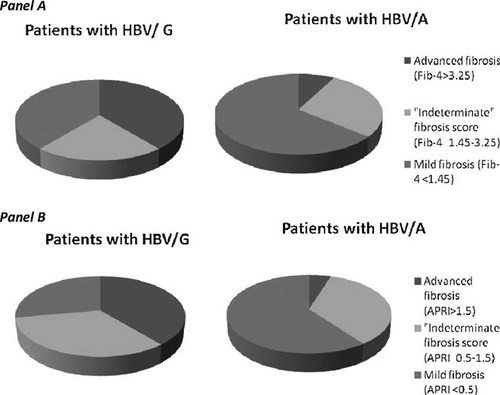

Panel A-Fib-4 scores: Patients with HBV/G have the following distribution of fibrosis scores: advanced (>3.25) 7, “indeterminate” (1.45–3.25) 4, and mild (<1.45) 7. Likewise, HBV/A patients' are: advanced 8, “indeterminate” 29, and mild 66. The analysis only considers patients with advanced or mild fibrosis scores and shows that HBV/G patients are associated with more advanced fibrosis score [7/14 (50%)] than those with HBV/A [8/74 (11%), P = 0.0003]. Panel B-APRI Scores: Patients with HBV/G have distribution of fibrosis scores as follow: advanced (>1.5) 7, “indeterminate” (0.5–1.5) 6, and mild (<0.5) 5. Likewise, patients with HBV genotype A (HBV/A) had the following fibrosis scores: advanced 5, “indeterminate” 36, and mild 62. Analysis only included patients with advanced or mild fibrosis scores and showed that HBV/G patients are associated with more advanced fibrosis score [7/12 (58%)] than those with HBV/A [5/67 (7%), P = 0.0004].

Definitions

Alcohol consumption was defined as low (if abstinent or occasional use of <2 drinks/day) or high (if >3 drinks/day) as noted by the provider on a patient's chart. Fib-4 and APRI, non-invasive serum markers, were used to assess fibrosis stage during the follow-up [Wai et al., 2003; Sterling et al., 2006]. Fib-4 scores were dichotomized to Metavir stage ≤1 (<1.45) and ≥stage 2 (>3.25). Likewise, APRI scores were dichotomized to Metavir stage ≤1 (<0.5) and ≥stage 2 (>1.5) Intermediate values were not assessed. Demographics data including ALT/AST, platelet counts, and age were used as variables in Fib-4 (Fib-4 = [Age (years) × AST]/[(platelets) × √ALT]) and APRI (APRI = (AST/40) × (100/platelets).

Statistical Analysis

For the purpose of this analysis, patients infected with HBV genotype A versus those infected with genotype G were examined, as these were the two most prevalent genotypes found in the cohort. Data were analyzed by Chi-squared for categorical variables and Wilcoxon Rank Sum for continuous variables. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Overall Patient Characteristics

Overall demographic data of the 133 patient cohort are depicted in Table I. Within this cohort, 103/133 (77%) were HBV/A and 30/133 (23%) were HBV non-A genotypes. Among the non-A genotypes, 18/133 (14%) were HBV/G, and 12/133 (9%) the remaining genotypes including: D 8/133 (6%), F 2/133 (1.5%), and H 2/133 (1.5%). Median age was 42 years (range: 22–64). Blacks comprised 49% (65/133) of the group followed by Whites (38%; 50/133) and Hispanics (11%; 14/133). The one Asian in the study was infected with genotype A. The majority of patients were male (84%, 112/133). Baseline HBV-DNA levels were high with median value of 8.0 log10 (range: 3.31–8.0) copies/ml. Baseline median HBeAg was >1,000 (range: 0–>1,000) and median anti-HBe titer was 0 (range: 0–4.5). Baseline median HIV viral load and CD4 T cell count was 4.75 (1.69–6.88) log10 copies/ml and 190 (1–1,132) cells/µl, respectively. Approximately 27% (36/133) of the patients were found to have anti-HCV positivity. Documented alcohol use within medical records revealed that 61% (35/57) were low risk drinkers; whereas, 39% (22/57) were high-risk drinkers. The duration of observation was nearly 3 years [median: 35; range (0–110) months]. History of medication use that was active against HBV was available in 89% (110/133) of the overall group and no significant difference was seen in the specific type of anti-HBV medication used between the various subgroups.

| Characteristics | Total (n = 133) | Genotype A (n = 103) | Genotype G (n = 18) | Univariate P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender [n(%), male] | 112 (84) | 86 (84) | 17 (94) | 0.23 | |

| Race [n(%)] | African American | 65 (49) | 56 (54) | 7 (39) | 0.60 |

| Caucasian | 50 (38) | 34 (33) | 9 (50) | ||

| Hispanics | 14 (11) | 9 (9) | 2 (11) | ||

| Others | 4 (3) | 3 (3) | 0 | ||

| Time interval of follow-up (months), median (range) | 35 (0–110) | 36 (0–101) | 26 (0–98) | 0.12 | |

| HCV antibody positive [n(%)] | 36 (27) | 28 (27) | 4 (22) | 0.66 | |

| Fibrosis Score [n(%)] | Mild Fibrosis (<1.45) | 82 (84) | 66 (89) | 7 (50) | |

| Advanced fibrosis (>3.25) | 16 (16) | 8 (11) | 7 (50) | 0.0003 | |

| HIV viral load (log10 copies/ml) | N | 122 | 93 | 17 | |

| Median (range) | 4.75 (1.69–6.88) | 4.77 (1.69–6.88) | 4.51 (1.69–55.88) | 0.86 | |

| CD4+ Count (cells/µL) | N | 123 | 94 | 17 | |

| Median (range) | 190 (1–1,132) | 169 (4–1,132) | 160 (1–609) | 0.81 | |

| HBV DNA titers (log10 copies/ml) | N | 133 | 103 | 18 | |

| Median (range) | 8.0 (3.31–8.0) | 8.0 (3.31–8.0) | 8.0 (4.05–8.0) | 0.32 | |

| HBeAg positivity | N | 116 | 89 | 17 | |

| [n(%)] | 98 (84) | 73 (82) | 17 (100) | 0.06 | |

| Anti-HBe positivity | N | 99 | 78 | 14 | |

| [n(%)] | 28 (18) | 21 (27) | 3 (21) | 0.67 | |

| Moderate/excessive alcohol use [n(%)] | 22 (39) | 19 (46) | 1 (10) | 0.07 |

Phylogenetic Analysis

Ninety-eight of the patients were genotyped by direct sequencing and 35 were done by Trugene®. Unfortunately, insufficient serum existed to re-test the Trugene® results by direct sequencing. From the 98 patients in which sequence data were available, a phylogenetic tree was generated. As seen in Figure 2, each genotype clusters together.

Phylogenetic tree was generated from sequences from 98 patients and a HBV reference sequence of each genotype. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method. This phylogenetic tree was drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted in MEGA4. ○ genotype A, ▪ Genotype B, ▴ genotype C,□ Genotype D, ◊ Genotype E, ♦ Genotype F, ● Genotype G, Δ Genotype H.

Comparison of HBV/G and HBV/A Groups

In a univariate analysis, several differences between patients infected with HBV/G and those infected with HBV/A were found as shown in Table II. HBV/G patients had higher median ALT values compared to patients infected with HBV/A (47 vs. 30, P = 0.045), as well as higher AST values (65 vs. 30, P = 0.004). For those infected with HBV/A, 27% were infected with HCV compared to 22% infected with HBV/G. HBV DNA levels were high in both HBV/G and HBV/A (8 log10 copies/ml for both). Eighty-two and 100% of patients with HBV/A and HB/G were HBeAg-positive, P = 0.67. The duration of observation from initial sample collection to last clinic follow-up in patients infected with HBV/G [median 26; range (0–98) months] was similar to patients infected with HBV/A [36 (0–101) months], P = 0.12. However, as shown in Tables IIIA and IIIB, patients infected with HBV/G had more advanced fibrosis of the liver assessed by Fib-4 (OR 8.25, 95% CI 2.3–29.6, P = 0.0012) or by APRI (OR 17.36, 95% CI 4.0–75.15, P = 0.0004. Being black appeared to be associated with lower risk for advanced fibrosis scores on univariate analysis as shown in Tables IIIA and IIIB. APRI was accessed in 87 patient of which 79 were either genotype A or G. Fifty-eight percent (7/12) of HBV/G had advanced fibrosis compared to those infected with HBV/A (7%, 5/67), P = < 0.0001 (Fig. 1, Panel B) Of the 98 patients with assessable Fib-4 scores, 88 patients were infected with HBV/A or HBV/G. No differences were found between those categorized by FIB-4 scores as having mild fibrosis versus those with advanced fibrosis with regard to gender, HBV-DNA titers, HBeAg, anti-HBe levels, percent of time on anti-HBV medications during follow-up, anti-HCV positivity, alcohol use, baseline HIV viral loads, and baseline CD4 T cell counts. Those with mild fibrosis scores were younger [median 41 years (22–58 years)] compared to those with advanced fibrosis scores [median 43 years (35–58 years), P = 0.04]. Platelet counts were higher in those with mild fibrosis scores [median 216 × 109/L (108–590 × 109/L)] compared to those with advanced fibrosis scores [87 × 109/L (35–234 × 109/L), P < 0.0001]. Patients infected with HBV/G had advanced liver fibrosis by FIB-4 scores more often (50%, 7/14) than patients infected with HBV/A (11%, 8/74), P = 0.009, similar to the result found by APRI fibrosis score (Fig. 1, panel A).

| Variables | Total (n = 133) | Genotype A (n = 103) | Genotype G (n = 18) | Univariate P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [median (range)] years | 42 (22–64) | 42 (22–64) | 39 (24–52) | 0.30 |

| ALT (IU/L) [median (range)] | 33 (7–196) | 30(8–196) | 47 (7–171) | 0.045 |

| AST (IU/L) [median (range)] | 34 (12–686) | 30 (14–686) | 65 (12–175) | 0.004 |

| PLATELETS [median (range)] (109/L) | 193 (35–590) | 193 (62–590) | 174 (35–326) | 0.46 |

| Variable | Univariate | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| HBV Genotype G | 8.25 (2.3–29.6) | 0.0012 |

| Blacksa | 0.19 (0.05–0.72) | 0.01 |

| Variable | Univariate | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| HBV Genotype G | 17.36 (4.0–75.15) | 0.0004 |

| Blacksa | 0.17 (0.04–0.83) | 0.029 |

- Univariate analysis revealed that HBV genotype (A vs. G), and race (Blacks vs. non-Blacks) are important predictors between advanced liver fibrosis (Fib-4 index > 3.25; APRI > 1.5) from mild liver fibrosis (Fib-4 index < 1.45, APRI < 0.5).

- a Blacks compared to non-Blacks.

DISCUSSION

The current study sought to determine the prevalence of HBV/G and whether this genotype was associated with more advanced fibrosis of the liver in those infected with HIV/HBV. This cohort of patients represents a racially diverse US population seen at an urban community-based hospital. The Dallas-Fort Worth region comprises more than 5 million residents consisting of 4% Asian, 14% African American, 69% Caucasian, and 22% Hispanic [http://www.texasfreeway.com/Dallas/dallas.shtml].

Similar to other studies, a high proportion (77%) of patients were infected with HBV/A [Soriano et al., 2007]. In a previous study, 33 patients infected with HIV/HBV were genotyped by sequence analysis of the S, pre-S2, and partial pre-S1 region. By this method, 12% of the cohort was infected with HBV/G. All four subjects in this study were HBeAg-positive and the authors postulated this finding was due to infection with mixed or recombinant strains [Zehender et al., 2003]. In a second study, HBV genotypes were determined using a DNA chip after amplifying the whole HBV genome. Approximately 12% of the cohort was infected with HBV/G but the authors did not report whether those infected with HBV G genotype were HBeAg-positive. Similar to the findings in the co-infected population [Stuyver et al., 2000; Zehender et al., 2003; Lacombe et al., 2006], 14% (n = 18/133) of the patients in this study were infected with HBV/G.

In HBV mono-infection, it is recognized increasingly that genotypes influence the natural history of disease progression and the likelihood of developing hepatocellular carcinoma. On the contrary, the prevalence and clinical significance of HBV genotypes in an HIV co-infected population is not well known. Limited information exists regarding infection with HBV/G, which appears to be globally distributed but relatively rare in HBV mono-infected persons [Kato et al., 2002a; Bottecchia et al., 2008; Osiowy et al., 2008].

Those infected with HBV/G appear to have a more aggressive progression of liver disease as compared to those infected with HBV/A based on higher fibrosis scores in those infected with HBV/G. A direct cytopathic effect of HBV/G has been implicated because of high levels of HBcAg found in livers of immunocompromised mice [Sugiyama et al., 2006], which may suggest a mechanism through which faster progression could occur. The risk for advanced fibrosis is stronger among those infected with HBV/G, but because of the small numbers, the confidence intervals are wide.

“Pure” HBV/G with the 12 amino acid insertion downstream of the core region induces modifications in both the encapsidation signal sequence and in the core protein structure causing a defect in secretion of virus and retention of viral products within infected hepatocytes [Junker-Niepmann et al., 1990; Li et al., 2007], thus yielding a low HBV viral load. In our study, patients infected with HBV/G had high HBV DNA levels. Furthermore, all patients were HBeAg-positive. Patients infected with HBV/G may have had high HBV DNA levels and HBeAg-positivity due to recombination with HBV genotype A or due to mixed infection. It is thought that HBV/G when mixed with other genotypes such as HBV/A, will regain HBV replication capacity, perhaps by utilizing the proteins produced by the dominant A genotype. Possible mechanisms involved in this enhancement include trans-complementation with core protein of other genotype (i.e., HBV/A) [Sugiyama et al., 2006], polymerase encoded by HBV/G in active replication [Kremsdorf et al., 1996], and/or other viral elements besides the core protein [Tanaka et al., 2008]. A pure HBV/G should be HBeAg-negative because of the mutations in the core and pre-core regions. Thus, HBV/G in patients infected with HIV appeared to have a different phenotype than expected. When patients are infected with HBV/G and have high HBV DNA levels and HBeAg-positivity this may indicate that the HBV/G exists in a mixed or recombined form.

This study was limited to sequence analysis to determine genotypes. Trugene® is an automated system which is reliable in identifying HBV genotypes but may not be as sensitive in identifying mixed infections as compared to INNO-LiPA[Roque-Afonso et al., 2003]. Direct sequencing is more accurate for determining recombination but not mixed infections, whereas, INNO-LiPA is more accurate in detecting mixed infections [Valsamakis, 2007]. Given that the methods used could not verify mixed infections versus recombination, either event could be possible. In order to determine if a mixed infection existed, a clonal analysis of HBV/G quasispecies or testing with INNO-LiPA would be needed.

Immunologically, whether HBeAg has any role in immunocompromised conditions deserves further study. In immunocompetent mice with HBV infected with one genotype, HBeAg acts like a decoy protein against the host immune response limiting liver damage [Milich et al., 1990]. Clinical observations have shown patients infected with HBV with one genotype who are HBeAg-negative have more liver fibrosis [Ghany and Seeff, 2006]. However, in the immunodeficient setting, there was no relationship between immune activity in patients infected with HIV/HBV who were HBeAg-negative as compared to those who were HBeAg-positive [Chang et al., 2009].

Liver biopsy is considered the gold standard method for determining the degree of fibrosis in the liver but has inherent limitations. The biopsy is invasive, subject to sampling error, and has poor intra- and inter-observer agreement among pathologists [Rockey et al., 2009]. These limitations have encouraged the development of non-invasive methods. Fib-4 and APRI are indirect biomarkers of fibrosis and are readily available at a low cost using clinical data such as ALTs, platelet counts, and the age of the patient [Sterling et al., 2006]. These two methods were chosen because they utilized laboratory parameters that are commonly used in clinical practice. Fib-4 has become widely used in viral hepatitis irrespective of etiology [Castera et al., 2007]. Non-invasive methods to measure fibrosis are particularly helpful in individuals co-infected with HIV and HCV or HBV for whom liver biopsies are less feasible due to patient and provider reluctance. Fib-4 has been shown to be more accurate than others non-invasive markers of fibrosis in HBV mono-infection or co-infection with HIV [Mallet et al., 2009]. In a study assessing Fib-4's accuracy in distinguishing between Metavir score system F0-2 versus F3-4 in patients co-infected with HIV/HBV, Bottero et al. [2009] showed that Fib-4 scores were concordant with results from liver biopsies with an adjusted area under the curve (AUC) of 82%. Other markers, which may perform better in patients infected with HIV, were not used in this study due to cost. [Bottero et al., 2009] Fib-4 was originally developed to differentiate Ishak 0–3 from Ishak 4 to 6 [Sterling et al., 2006], but these indices <1.45 (Ishak 0–3) and >3.25 (Ishak 4–6) have been comparably utilized in Metavir model equivalent to F0-2 and F3-4, respectively [Vallet-Pichard et al., 2006; Adler et al., 2008]. A cut off value of <1.45 has a negative predictive value to exclude advanced fibrosis (Ishak 4–6 or Metavir F3–4) of 90% with a sensitivity of 70%, and a cut off value of >3.25 had a positive predictive value of 65% and a specificity of 97%. Use of these cut offs can offer several advantages including: reduction of the need to perform liver biopsies in patients at the ends of the fibrosis spectrum and utilization of the non-invasive methods multiple times to monitor longitudinal disease progression and the therapeutic efficacy of anti-viral treatments on liver fibrosis. However, APRI and Fib-4 scores may be limited because low platelet counts and abnormal LFTS may be due to HIV and not liver disease.

This study occurred in a multi-cultural US environment which allowed the opportunity to study patients of different races. Whether racial differences influence HBV disease progression remains unclear [Nguyen and Thuluvath, 2008]. In the univariate model (Tables IIIA and IIIB), being Black is associated with mild fibrosis compared with non-Blacks; similar findings have been observed in patients with hepatitis C [Pearlman, 2006].

To determine the duration of HBV infection in the HIV/HBV co-infected population was challenging to obtain. Even when a history was available, it was subject to recall bias from the patient and ascertainment bias by the provider. Additionally, patients co-infected with HIV/HBV, who had low CD4 T cell counts were unlikely to have experienced clinical hepatitis and would be less likely to recognize when an initial infection occurred. Using chart reviews, history of HBV infection was obtained in only 32% (43/133) of the studied patients. Given these limitations, both median and mean times from first HBV infection to last clinical follow-up were similar between the two genotype groups. Additionally, if age is used as a surrogate for duration of infection, patients infected with HBV/A had a median age of 42 years compared to those infected with HBV/G who had a median age of 39 years. The overwhelming majority of patients were not from countries in which HBV is endemic, and, therefore, their mode of disease acquisition was most likely sexual or due to intravenous drug use.

A multivariable analysis was not performed because the number of patients with advanced fibrosis was too small to allow this type of modeling. Thus, factors such as age, duration of follow-up, and race may confound these findings. Another limitation of this study was that data on HIV regimen was not obtained. HIV-related hepatotoxicity may have been another confounder in the study.

In conclusion, the presence of HBV/G was associated with advanced liver fibrosis in patients co-infected with HIV/HBV as suggested by Fib-4 and APRI. Patients infected with HBV/G had high HBV DNA levels and were HBeAg-positive. Further studies are needed to determine if HBV/G recombines or exist as mixed genotypes. HBV genotyping appears to be of value in predicting advanced fibrosis in HIV co-infected patients. Black race also was a predictor of milder fibrosis. Prospective studies with liver biopsies are needed with patients of different genotypes and racial backgrounds to establish a causal relationship between these factors and fibrosis progression.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the review of this manuscript by Professor Masashi Mizokami and for the participation of all the patients in this study. Siemens Diagnostics provided HBeAg and anti-HBe ADVIA® Centaur assay kits.