Hepatitis B virus and sexual behavior in Rakai, Uganda†‡

Research performed by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA at the Rakai Health Sciences Program, Entebbe Uganda.

This is a US Government work, and as such, is in the public domain in the United States of America.

Abstract

HIV and hepatitis B virus (HBV) co-infection poses important public health considerations in resource-limited settings. Demographic data and sera from adult participants of the Rakai Health Sciences Program Cohort in Southwestern Uganda were examined to determine HBV seroprevalence patterns in this area of high HIV endemicity prior to the introduction of anti-retroviral therapy. Commercially available EIAs were used to detect prevalent HBV infection (positive for HBV core antibody [anti-HBc] and/or positive HBV surface antigen [HBsAg]), and chronic infection (positive for HBsAg). Of 438 participants, 181 (41%) had prevalent HBV infection while 21 (5%) were infected chronically. Fourteen percent of participants were infected with HIV. Fifty three percent showed evidence of prevalent HBV infection compared to 40% among participants infected with HIV (P = 0.067). Seven percent of participants infected with HIV were HBsAg positive compared to 4% among participants not infected with HIV (P = 0.403). The prevalence of prevalent HBV infection was 55% in adults aged >50 years old, and 11% in persons under 20 years. In multivariable analysis, older age, HIV status, and serologic syphilis were significantly associated with prevalent HBV infection. Transfusion status and receipt of injections were not significantly associated with HBV infection. Contrary to expectations that HBV exposure in Uganda occurred chiefly during childhood, prevalent HBV infection was found to increase with age and was associated sexually transmitted diseases (HIV and syphilis.) Therefore vaccination against HBV, particularly susceptible adults with HIV or at risk of HIV/STDs should be a priority. J. Med. Virol. 83:796–800, 2011. © 2011 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a significant global public health problem; an estimated 2 billion people have evidence of prior infection and 350–400 million persons are infected chronically [WHO, 2008]. Around 20% of persons who are infected chronically may develop cirrhosis, liver failure, or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC); and there are approximately 620,000 HBV-related deaths annually [Fattovich et al., 1991; Goldstein et al., 2005].

HIV infection significantly impacts the course of HBV infection, leading to accelerated liver disease and increasing mortality up to eightfold compared to those infected by HIV alone [Thio et al., 2002]. Estimates of the prevalence of HBV co-infection among HIV-infected Africans vary from approximately 5 to 25% but the prevalence and epidemiology of HIV–HBV co-infection is unknown in many sub-Saharan African populations [Modi and Feld, 2007].

Improved understanding of the dynamics of HBV infection in the setting of HIV could inform HBV prevention strategies including both vaccination efforts and treatment strategies for HIV/HBV co-infected persons in Africa. Therefore, this study was designed to investigate the prevalence and correlates of HBV infection among an adult population in rural Uganda with high HIV prevalence prior to the availability of anti-retroviral therapy (ART).

METHODS

Study Site and Participants

The study was conducted in the Rakai District in rural southwestern Uganda. Serum and questionnaire data for serologic testing were obtained from a random sample of participants aged 15–59 years enrolled in the population-based Rakai Community Cohort Study (RCCS). Archived RCCS participant specimens and data collected in 1998 were used in this study to ascertain the prevalence of HBV markers prior to any substantial introduction of ART in this region, as some anti-retroviral drugs are also active against HBV and could affect transmission patterns.

Since 1994, the RCCS has collected detailed longitudinal data on HIV epidemiology and risk factors for HIV infection, including exposure to blood transfusions and possible unsafe injections, many of which are also risk factors for HBV. Over 12,000 adults have been enrolled in this open cohort with follow-up at 10–12 month intervals. Detailed socio-demographic and risk behavior interviews are conducted, along with collection of serum which is archived at −80°C. Informed consent is obtained from all participants. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approvals for the RCCS were obtained from the Uganda Virus Research Institute's Science and Ethics Committee, the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, and from the Committee for Human Research at the Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health and Western IRB in the United States.

Laboratory Testing

A random sample of serum samples were tested for markers of HBV infection (antibodies to HBV core antigen, anti-HBc) and (HBV surface antigen, HBsAg) at the Infectious Disease Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University. Testing was performed using commercial reagents (Genetic Systems HBsAg EIA 3.0 kit and Diasorin ETI-AB-COREK PLUS kits) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Serologic test results from the same study visit for HIV and syphilis were available from prior analysis, as previously described [Kiddugavu et al., 2005].

Statistical Analysis

Demographic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics were compared between persons with and without anti-HBc or HBsAg expression using chi-squared and t-tests. The association between prevalent HBV infection (any marker positive) and chronic HBV infection (positive for HBsAg) were assessed by estimating univariate and adjusted prevalence risk ratios (PRR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) using log binomial regression. All variables with P < 0.1 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model presented. Analyses were performed using STATA statistical software (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Study Participants

The median age of the study population was 40 years (IQR, 31–50; Table I). Overall, 243 (55%) were female. Two-thirds of participants reported having more than two lifetime sexual partners. Serologic evidence of syphilis infection was detected in 8% while 14% of participants were HIV infected. Recent medically related injections were reported by 42% of participants. However, lifetime history of a transfusion was rare (2%).

| n = 438a | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Age distribution (years) | ||

| <20 | 37 | 8 |

| 20–29 | 66 | 15 |

| 30–49 | 227 | 52 |

| ≥50 | 108 | 25 |

| Male gender | 195 | 45 |

| No. of lifetime sex partners | ||

| 0–2 | 147 | 34 |

| 3+ | 289 | 66 |

| Regularly use condoms | 35 | 8 |

| Prior blood transfusion | 7 | 2 |

| Recent medical injections | 183 | 42 |

| HIV-1 positive | 59 | 14 |

| Syphilis seroreactiveb | 37 | 8 |

- a Numbers may not sum exactly due to missing data.

- b Reactive on nontreponemal screening test, including reactive plasma region (RPR) or toludine red unheated serum test (TRUST).

HBV Prevalence

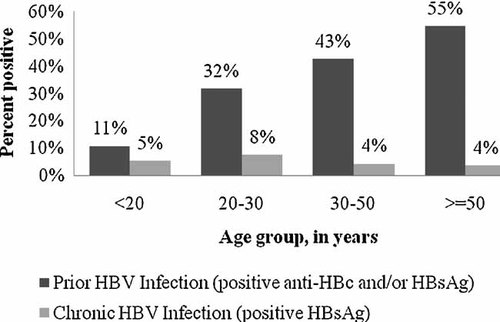

Within this adult population, 181 (41%) expressed anti-HBc and/or HBsAg as evidence of prevalent HBV infection. However, chronic infection (HBsAg positive) was infrequent (n = 21, 5%). Prevalent HBV infection increased with age, from 11% in the 15–19 age group to 55% in those 50 or older (P < 0.001; Fig. 1). In contrast, HBsAg prevalence peaked at 8% among participants 20–29 years of age and was lower in older age groups (4%; P = 0.242), however age differences were not statistically significantly different. There were no differences in prevalent HBV infection among males was compared to among females (43% vs. 40%; P = 0.637). There were also no gender differences in chronic HBV infection (5% in both in males and females).

Prevalence of HBV markers by age.

Correlates of Prior HBV Infection (Anti-HBc and/or HBsAg Positivity)

In addition to age, prevalent HBV infection was more common in participants reporting more than two lifetime sexual partners (46% vs. 31%; P = 0.002) and in those with a serologic reactivity to syphilis (59% vs. 40%; P = 0.019). HBV infection was also more common among HIV-infected persons (53% vs. 40%; P = 0.067), but the difference was not statistically significant. No significant difference in prevalent HBV infection was observed in those reporting consistent condom use. Prevalent HBV infection was also not associated with gender or receipt of injections or transfusions in the previous year. (Table II).

| Univariate prevalence risk ratios | 95%CIb | P-value | Multivariate prevalence risk ratiosc | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groupd | ||||||

| <20 | 1.0 (ref) | — | ||||

| 20–29 | 2.94 | 1.09–7.93 | 0.033 | 2.63 | 0.98–7.12 | 0.056 |

| 30–49 | 3.95 | 1.54–10.10 | 0.004 | 3.37 | 1.31–8.66 | 0.012 |

| ≥50 | 5.05 | 1.97–13.0 | 0.001 | 4.37 | 1.70–11.2 | 0.002 |

| Male gender | 1.06 | 0.84–1.32 | 0.636 | 1.07 | 0.85–1.35 | 0.566 |

| 3+ Lifetime sex partners | 1.51 | 1.15–1.99 | 0.003 | 1.27 | 0.95–1.69 | 0.101 |

| Regularly use condoms | 1.11 | 0.76–1.63 | 0.569 | |||

| Prior blood transfusions | 1.39 | 0.75–2.67 | 0.320 | |||

| Recent medical injections | 1.01 | 0.80–1.26 | 0.941 | |||

| HIV-1 infected | 1.31 | 1.00–1.73 | 0.048 | 1.31 | 1.00–1.71 | 0.046 |

| Syphilis seroreactivee | 1.49 | 1.12–2.01 | 0.007 | 1.35 | 1.01–1.79 | 0.039 |

- a HBV infection defined as expression of anti-HBc and/or HBsAg.

- b CI, confidence intervals.

- c All variables with P < 0.1 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model.

- d Age in years.

- e Reactive on nontreponemal screening test, including reactive plasma reagin (RPR) or toludine red unheated serum test (TRUST).

The results of univariate and multivariate regression analysis are given in Table II. In univariate analysis, both age in years (PRR 1.04, 95% CI 1.02–1.05; P < 0.001) and age group were significant predictors of HBV exposure. The increasing risk with age remained statistically significant in adjusted analyses. Three or more lifetime sexual partners were significantly associated with HBV in univariate analyses (PRR 1.51, 95% CI 1.15–1.99; P = 0.003), but not after adjustment (Adj PRR 1.27, 95%CI 0.95–1.69). HIV infection (univariate PRR 1.31, 95% CI 1.00–1.73; P = 0.048, adjusted PRR 1.31, 95%CI 1.00–1.71, P = 0.046)) and serologic syphilis (univariate PRR 1.49, 95% CI 1.12–2.01; P = 0.007, adjusted PRR 1.35, 95%CI 1.01–1.79, P = 0.039) were both statistically significant predictors of HBV exposure. Gender, condom use, exposure to blood transfusions, and injections were not significant predictors of HBV exposure.

The number of chronic HBV infections was small (n = 21), and there was no statistically significant difference in HBsAg positivity observed with any covariates.

DISCUSSION

Global variation in the burden of HBV-related disease is substantial in part due to variation in the modes of transmission and natural history of infection [Alter, 2003]. In Western countries, HBV infection is infrequent and is mainly transmitted among young adults through sexual or parenteral routes [Goldstein et al., 2002; Hahne et al., 2004; Spada et al., 2001].

In Africa, most HBV infections are traditionally thought to occur in young children through close contact with household contacts, ritual scarification, and other mechanisms, with exposure to HBV occurring before the age of sexual debut [Whittle et al., 1990; Abdool Karim et al., 1991; Martinson et al., 1998]. Subsequently, with high HBV chronicity following childhood exposure [Edmunds et al., 1996], estimates of chronic HBV infection approach 20% in some African countries [Whittle et al., 1983].

In contrast, in this study there was evidence of HBV exposure increasing with age (Fig. 1) in adulthood suggesting ongoing adult transmission associated with a low prevalence of chronic HBV. In this study, HBV exposure was also significantly associated with HIV infection, syphilis, and increased number of lifetime sexual partners, suggesting that the ongoing HBV transmission in adulthood could be sexual, as has been reported in some other African countries [Van de Perre et al., 1987; Bile et al., 1991; Jacobs et al., 1997; Abebe et al., 2003].

According to a recent national serosurvey in Uganda, the prevalence of chronic HBV infection was 10%, with regional variation from 18 to 24% in northern and West Nile regions to 4% in southwestern Uganda [Macro, 2006]. These data are compatible with the study population from rural southwestern Uganda presented in this paper. Although there are limited data, lower chronic HBV prevalence in this region also appears consistent for at least 20 years. One study conducted in 1986 at two hospitals in Southwest Uganda, showed a 5% prevalence of chronic HBV [Hudson et al., 1988]. Sero-surveys in neighboring countries show a similar prevalence of HBsAg positivity of 5–9% in Tanzania [Hasegawa et al., 2006; Matee et al., 2006; Msuya et al., 2006] and 2.4% in Rwanda [Pirillo et al., 2007].

Sexual transmission in adulthood is the most likely risk factor for adult HBV transmission in Rakai, Uganda. In Southwestern Uganda, there are low rates of scarification, and this is not practiced in Rakai. Other parenteral modes of HBV transmission, including receipt of medical injections and blood transfusions were not associated with HBV infection in this study. Similarly, in a prior Rakai study, medical injections are also not associated with incident HIV infection, although blood transfusions were associated with HIV infection [Kiwanuka et al., 2004].

Transmissibility and pathogenesis of HBV genotypes could also potentially account for regional variation in HBV infection in Uganda. However, little is known about differences in transmissibility and pathogenicity of genotypes inAfrican setting. A small pilot study (n = 31 samples) conducted in the capital city of Kampala, Uganda, about 3 hr driving distance from Rakai, showed a predominance of genotype A [Seremba et al., 2010].

Although HBV surface antibody was not tested in this study, HBV vaccination was unlikely to play a role in the low rates of infection and chronicity, as the samples and questionnaire data were from 1998, before HBV vaccination was available in this district. HBV was introduced into the infant vaccination program in 2002 and officially reported coverage rates were 83% in 2009, but WHO-UNICEF estimates of the HBV infant vaccine coverage were 64% in the same year [WHO, 2010].

The lower childhood transmission of HBV in this population and the relatively recent introduction of infant HBV vaccination, indicates that there may be a high prevalence of susceptible young adults at risk of sexual transmission of HBV. There are substantial implications for HIV programs in the region. Similar to prior Ugandan studies [Nakwagala and Kagimu, 2002; Bwogi et al., 2009], prevalent HBV infection was associated with HIV-infection in this study. Besides being at higher risk for infection due to shared modes of transmission, HIV-infected persons are also more likely to develop chronic infection and are at higher risk for progressive disease [Thio et al., 2002]. Adult vaccination of HIV-infected persons where HBV exposure uniformly occurs before adulthood may not be needed, but in areas similar to Southwestern Uganda, with an older age of infection, vaccination of HIV-infected adults may be indicated. Unfortunately, at this time, routine HBV testing and vaccination as indicated is rarely performed for patients infected with HIV in resource-limited settings.

Similarly, HIV–HBV treatment strategies could improve as a result of better knowledge of regional HBV epidemiology. Of the drugs used to treat HBV, lamivudine, emtricitabine, and tenofovir can also be used to treat HIV. Because HBV testing is often not available in resource-limited settings, patients are often empirically started on lamivudine containing regimens. The preferred regimen including dual therapy for HBV co-infection with tenofovir has been used less frequently, although tenofovir containing HIV regimens are now recommended as a first line therapy in some African countries, including in Uganda. Prioritizing the introduction of HIV regimens containing dual therapy for HBV in regions with a high prevalence of HBV or testing patients infected with HIV for chronic HBV, may improve HIV–HBV treatment outcomes.

Further efforts are clearly needed to describe better the epidemiology of HBV in Africa, especially in regions of high HIV prevalence. A better understanding of HBV transmission dynamics, molecular characteristics, and rates of progression, particularly with HIV co-infection, are essential for projecting the burden of liver disease in Africa. However, over the long term, HBV screening and vaccination offers a relatively low-cost intervention which could potentially optimize the health benefits from the substantial investments in anti-retroviral programs.