Potential of PALBI-T score as a prognostic model for hepatocellular carcinoma in alcoholic liver disease

Declaration of conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest associated with this study.

Abstract

Background and Aim

With the control of viral hepatitis, alcoholic hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is becoming increasingly important in Japan. In alcoholic cirrhosis, the impact of portal hypertension is significant. Thus, it may be difficult to predict prognosis accurately with the reported prognostic scores. Here we propose the platelet-albumin-bilirubin tumor nodes metastasis (TNM) score (PALBI-T score) as a prognostic model for HCC in alcoholic liver disease, and investigate its usefulness. The PALBI-T score is an integrated score based on the TNM stage and PALBI grade including platelets, reflecting portal hypertension.

Methods

This study included 163 patients with alcoholic HCC treated at our Center from 1997 to 2018. We compared the prognostic prediction abilities of the Japan Integrated Staging (JIS) score, ALBI-T score, and PALBI-T score. The PALBI-T score was calculated similarly to the JIS and ALBI-T scores. Areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) were calculated for predicting overall survival (OS).

Results

In predicting the 1-year survival, the JIS score had a larger AUC (AUC = 0.925) than the ALBI-T score (AUC = 0.895) and PALBI-T score (AUC = 0.891). On the other hand, there was no significant difference in predicting OS among the integrated scores. The PALBI-T score (AUC = 0.740) had the largest AUC, and the JIS score (AUC = 0.729) and ALBI-T score (AUC = 0.717) were not significantly different from the PALBI grade (AUC = 0.634). The PALBI grade reflected the degree of portal hypertension.

Conclusion

In patients with alcoholic HCC, the Japan Integrated Staging score is useful for predicting short-term prognosis. The PALBI-T score, which reflects portal hypertension, appears to be a more valid prognostic score for predicting long-term prognosis.

Introduction

With the prevention and control of hepatitis C and B viruses, the frequency of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) resulting from viral liver injury has decreased in Japan. On the other hand, the number of patients with non-viral HCC has gradually increased, currently ranging from 15 to 30%.1-3 About one-half of these patients are reported to have alcoholic HCC.4 Alcohol consumption is a common cause of HCC in Europe.5, 6 In Japan, the incidence of alcoholic HCC has been increasing.

Hepatic function has been commonly assessed by the Child–Pugh (CP) class.7 However, this method has been problematic because it includes confounding factors such as albumin and ascites, besides lacking objectivity due to subjective factors such as ascites and hepatic encephalopathy.8 Recently, the albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grade has been proposed, which can evaluate hepatic reserve function using only albumin and bilirubin.8 Its usefulness has been due to its simplicity and objectivity. Specifically, the prognostic value of the ALBI-T score has been reported.9 This is an integrated score, which consists of the ALBI grade with the TNM staging of the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan (LCSGJ).10

However, most of the previously reported ALBI grades and ALBI-T scores are focused on viral HCC. To our knowledge, there has been no report that focuses on alcoholic HCC. Portal hypertension (PH) is associated with alcoholic cirrhosis and has a significant impact on the prognosis of patients with HCC.11-13 In recent years, the platelet-albumin-bilirubin score (PALBI score), which includes platelets in addition to albumin and bilirubin, has been reported for evaluating hepatic function, which also takes into account PH.14, 15

In the present study, we retrospectively evaluated the usefulness of the platelet-albumin-bilirubin TNM score (PALBI-T score) as a prognostic model in patients with alcoholic HCC.

Methods

Patients

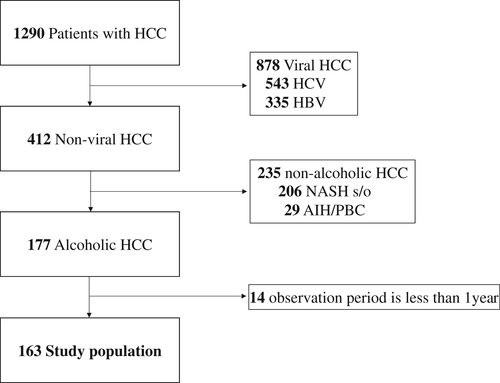

Patients with alcoholic HCC diagnosed at our institute between April 1997 and December 2018 were enrolled in this study. Patients with a follow-up period of <1 year were excluded. The criteria for alcoholic HCC were excessive alcohol consumption of >60 g/day for 5 years or more, and negative results for hepatitis virus markers, antimitochondrial antibodies, and antinuclear antibodies16 (Fig. 1). The diagnostic criteria for HCC were based on hyperattenuation at the arterial phase or at the portal phase, as determined using dynamic computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with tumor staining on angiography.10

The treatment of HCC is based on the Japan Society of Hepatology Clinical Practice Guidelines for HCC.17-19 HCC patients with preserved liver function and within the Milan criteria were treated by surgery or radiofrequency ablation, whereas those not within the Milan criteria were treated by transcatheter arterial chemoembolization or systemic chemotherapy. Patients who received initial treatment were screened using blood tests every 3 months and CT or MRI every 6 months. Patients with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia were considered to be on medication. The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines in the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association and was approved by our Institutional Review Board.

Grading and staging systems of hepatic function and prognosis

Hepatic reserve function at the time of HCC diagnosis was calculated using the CP class, ALBI grade, and PALBI grade. Tumor stage was evaluated using the Barcelona Clinical Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage20 and TNM stage of LCSGJ. The Japan integrated staging (JIS) score,21 ALBI-T score, and PALBI-T score were calculated by combining the hepatic reserve function and TNM stage at diagnosis. The descriptions of the grades and scores are detailed below.

ALBI grade8: The cut points of this linear predictor place patients with a calculated score of ≤−2.60 into ALBI grade 1, those with a score of >−1.39 into ALBI grade 3, and those in between into ALBI grade 2. The equation for the linear predictor is (log10 bilirubin × 0.66) + (albumin × −0.085), where bilirubin is expressed in mmol/L and albumin in g/L.

PALBI grade14: The PALBI score was calculated as (2.02 × Log10 bilirubin) + [−0.37 × (Log10 bilirubin)2] + (−0.04 × albumin) + (−3.48 × Log10 platelets) + [1.01 × (Log10 platelets2)]. The PALBI grade was assigned based on 50 and 85% Cox cut points: PALBI 1, ≤−2.53; PALBI 2, −2.53 to −2.09; PALBI 3, >−2.09.

JIS score21: The JIS score was obtained by adding the TNM stage from the LCSGJ (fifth edition) to the CP class and then subtracting 2. Patients were graded from 0 to 5.

ALBI-T score9: The ALBI-T score was obtained by adding the TNM stage from the LCSGJ (fifth edition) to the ALBI grade and then subtracting 2. Patients were graded from 0 to 5.

PALBI-T score: The PALBI-T score was obtained by adding the TNM stage from the LCSGJ (fifth edition) to the PALBI grade and then subtracting 2. Patients were graded from 0 to 5.

Evaluation of portal hypertension

The criteria for portal hypertension were based on the clinically relevant portal hypertension (CRPH) grading proposed by Choi et al.22 as follows: (i) presence of portosystemic collateral veins on upper gastrointestinal endoscopy or CT; (ii) presence of ascites requiring treatment on CT; and (iii) splenomegaly on CT (length ≥12 cm), and a platelet count of <100 000/mm3. The degree of PH was assessed by classifying patients into three groups: those who did not meet all the three criteria; those who met one of the criteria; and those who met to or more criteria.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Easy R (EZR; Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan).23 Fisher's exact test was used for the analysis of quantitative data. Mann–Whitney's U test, generalized Wilcoxon test, and Cox regression analysis were used for continuous quantity data. The discriminatory abilities of the scoring models were assessed using the Akaike information criterion (AIC). The prognostic value of each score was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC). Differences in the AUCs were compared using a Delong test. A P-value of <0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference for all analyses.

Results

Baseline characteristics

From 1997 to 2018, 1290 cases of HCC were diagnosed in our Center. The number of alcoholic cases was 177 (14%). A total of 163 patients who could be followed up for more than 1 year were included in the analysis. The median age of the patients was 67 years (range 33–84), and 154 (94.4%) were men, with a body mass index of 23.7 (interquartile range [IQR] 14.8–37.1). The daily alcohol consumption was 100 g/day (IQR 60–360). PH was complicated in 117 patients (71.8%), with esophageal varices (EV) in 53 patients (32.5%), portosystemic collateral veins other than EV in 41 patients (25.2%), and splenomegaly in 80 patients (49.1%).

The following results were also obtained. CP classes A, B, and C: n = 107, 50, 6; ALBI grades 1, 2, and 3: n = 47, 99, 17; PALBI grades 1, 2, and 3: n = 40, 49, 74 (Table 1). There were 79 patients (48.5%) who had a single tumor, and the median tumor diameter was 35.0 mm (IQR 17.0–60.5 mm). The number of patients within the Milan criteria was 81 (49.7%). The BCLC stage was classified as 0, A, B, C, and D: n = 34, 62, 41, 20, 6. The LCSGJ TNM stage was classified as I, II, III, IVA, and IVB: n = 36, 52, 52, 16, 7. Radiofrequency ablation was performed in 96 patients (58.9%) as initial treatment and surgical resection in 44 patients (26.9%) (Table 2).

| n = 163 | ||

|---|---|---|

| n/median | %/IQR | |

| Age (years) | 67.4 | 61.1–74.0 |

| Gender (men) | 154 | 94.4 |

| BMI | 23.7 | 21.3–25.8 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.6 | 3.1–4.0 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.8 | 0.7–1.4 |

| ALP (U/L) | 367 | 252–532 |

| AST (U/L) | 50 | 38–81 |

| ALT (U/L) | 41 | 26–58 |

| γGT (U/L) | 210 | 87–461 |

| Platelet (×104/μL) | 12.9 | 8.5–18.5 |

| PT activity (%) | 77 | 66.9–91.0 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 10.2 | 4.5–36.8 |

| DCP (mAU/mL) | 97 | 25.8–869.5 |

| Daily amount of drinking (g/day) | 100 | 68–130 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 87 | 53.3 |

| Dyslipidemia | 14 | 8.5 |

| Hypertension | 72 | 44.1 |

| Portal hypertension | 117 | 71.8 |

| EV | 53 | 32.5 |

| Collateral | 41 | 25.2 |

| Splenomegaly | 80 | 49.1 |

| Ascites | 32 | 19.6 |

| Child–Pugh class | ||

| A | 107 | 65.6 |

| B | 50 | 30.7 |

| C | 6 | 3.7 |

| ALBI grade | ||

| 1 | 47 | 28.8 |

| 2 | 99 | 60.7 |

| 3 | 17 | 10.4 |

| PALBI grade | ||

| 1 | 40 | 24.5 |

| 2 | 49 | 30.1 |

| 3 | 74 | 45.4 |

- γGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; DCP, des-γ-carboxy prothrombin; EV, esophageal varices; IQR, interquartile range; PALBI, platelet-albumin-bilirubin; PT, prothrombin time.

| n = 163 | ||

|---|---|---|

| n/median | %/IQR | |

| Number of nodules | ||

| 1 | 79 | 48.5 |

| 2 | 28 | 17.2 |

| 3 | 17 | 10.4 |

| ≥4 | 39 | 23.9 |

| Maximum size, mm | 35.0 | 17.0–60.5 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | ||

| Yes | 16 | 9.8 |

| No | 147 | 90.2 |

| Extrahepatic metastasis | ||

| Yes | 7 | 4.3 |

| No | 156 | 95.7 |

| Milan criteria | ||

| In | 81 | 49.7 |

| Out | 82 | 50.3 |

| BCLC stage | ||

| 0 | 34 | 20.9 |

| A | 62 | 38.0 |

| B | 41 | 25.2 |

| C | 20 | 12.3 |

| D | 6 | 3.7 |

| TNM stage (LCSGJ) | ||

| I | 36 | 22.1 |

| II | 52 | 31.9 |

| III | 52 | 31.9 |

| IVA | 16 | 9.8 |

| IVB | 7 | 4.3 |

| Treatment modalities | ||

| Curative treatment | ||

| Resection | 44 | 26.9 |

| RFA | 52 | 31.9 |

| Total | 96 | 58.9 |

| Palliative treatment | ||

| Transarterial chemoembolization | 33 | 20.3 |

| Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy | 14 | 8.6 |

| Systemic therapy | 3 | 1.8 |

| Best supportive care | 17 | 10.4 |

| Total | 78 | 41.1 |

- BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer group; IQR, interquartile range; LCSGJ, Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; TNM, tumor nodes metastasis.

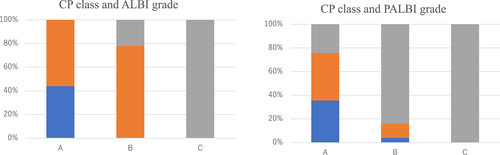

Stratification of CP class according to ALBI grade and PALBI grade

The distributions of ALBI grade and PALBI grade for each CP class are shown in Figure 2. CP class A patients (n = 107) consisted of 47 (43.9%) and 60 (56.1%) patients with ALBI grade 1 and ALBI grade 2, respectively. CP class B patients (n = 50) were composed of 39 (78%) patients with ALBI grade 2 and 11 (22%) patients with ALBI grade 3. CP class C patients consisted of 6 (100%) patients with ALBI grade 3.

), G1; (

), G1; ( ), G2; (

), G2; ( ), G3.

), G3.On the other hand, PALBI grade showed a different distribution from ALBI grade. CP class A (n = 107) consisted of 38 (36%), 43 (40%), and 26 (24%) patients with PALBI grade 1, grade 2, and grade 3, respectively. CP class B was composed of 2 (4%), 6 (12%), and 42 (84%) patients with PALBI grade 1, grade 2, and grade 3, respectively. CP class C was composed of six (100%) patients with PALBI grade 3.

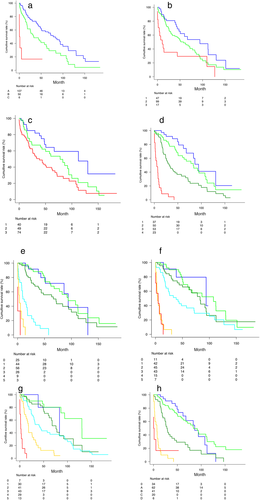

Overall survival according to hepatic function grade and integrated score

The median observation period for censored cases was 49.2 months (IQR 27.1–72.8). During the observation period, there were 99 deaths whose causes were HCC (67), liver failure (7), other carcinomas (6), infection (4), sudden death (3), unknown (4), and others (8). The median survival time was 59.4 months. The prognostic value of hepatic reserve function and the integrated score are shown in Figure 3(a–h). CP class, ALBI grade, and PALBI grade reflected the prognosis. Although all the integrated scores were able to stratify the survival of the patients, in the Cox proportional hazards model the PALBI-T score showed the best prognostic stratification among the three integrated scores (Table 3). It was difficult to stratify score 0 and score 1 in all the integrated scores. It was also difficult to stratify score 4 and score 5 in the JIS score and ALBI-T score. However, the PALBI-T score could discriminate score 4 and score 5.

), A; (

), A; ( ), B; (

), B; ( ), C. b: albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grade (

), C. b: albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grade ( ), 1; (

), 1; ( ), 2; (

), 2; ( ), 3. c: platelet-albumin-bilirubin (PALBI) grade (

), 3. c: platelet-albumin-bilirubin (PALBI) grade ( ), 1; (

), 1; ( ), 2; (

), 2; ( ), 3. d: LCSGJ stage (

), 3. d: LCSGJ stage ( ), I; (

), I; ( ), II; (

), II; ( ), III; (

), III; ( ), IV. e: Japan Integrated Staging (

), IV. e: Japan Integrated Staging ( ), 0; (

), 0; ( ), 1; (

), 1; ( ), 2; (

), 2; ( ), 3; (

), 3; ( ), 4; (

), 4; ( ), 5. f: ALBI tumor (ALBI-T) (

), 5. f: ALBI tumor (ALBI-T) ( ), 0; (

), 0; ( ), 1; (

), 1; ( ), 2; (

), 2; ( ), 3; (

), 3; ( ), 4; (

), 4; ( ), 5. g: PALBI tumor (PALBI-T) (

), 5. g: PALBI tumor (PALBI-T) ( ), 0; (

), 0; ( ), 1; (

), 1; ( ), 2; (

), 2; ( ), 3; (

), 3; ( ), 4; (

), 4; ( ), 5. h: Barcelona Clinical Liver Cancer (

), 5. h: Barcelona Clinical Liver Cancer ( ), 0; (

), 0; ( ), A; (

), A; ( ), B; (

), B; ( ), C; (

), C; ( ), D.

), D.| HR | 95% CI | P-value | AIC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JIS score | 0–1 | 1.00 | 0.42–2.38 | 0.992 | 769.417 |

| 1–2 | 1.77 | 1.03–3.03 | 0.037 | ||

| 2–3 | 4.91 | 2.73–8.84 | <0.001 | ||

| 3–4 | 3.29 | 1.39–7.73 | 0.006 | ||

| 4–5 | 3.24 | 0.76–13.84 | 0.112 | ||

| ALBI-T score | 0–1 | 0.98 | 0.28–3.46 | 0.981 | 794.739 |

| 1–2 | 1.43 | 0.77–2.64 | 0.256 | ||

| 2–3 | 1.69 | 0.98–2.90 | 0.056 | ||

| 3–4 | 7.41 | 3.58–15.41 | <0.001 | ||

| 4–5 | 1.28 | 0.51–3.23 | 0.597 | ||

| PALBI-T score | 0–1 | 0.93 | 0.10–8.11 | 0.95 | 784.444 |

| 1–2 | 2.45 | 1.13–5.33 | 0.024 | ||

| 2–3 | 1.62 | 0.91–2.89 | 0.098 | ||

| 3–4 | 1.42 | 1.16–1.73 | 0.001 | ||

| 4–5 | 7.94 | 3.39–18.53 | <0.001 |

- AIC, Akaike information criterion; ALBI-T, albumin-bilirubin tumor; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; JIS, Japan Integrated Staging; PALBI-T, platelet-albumin-bilirubin tumor.

Discriminatory powers of CP, ALBI grade, PALBI grade, JIS, ALBI-T, and PALBI-T

The ability of CP class, ALBI grade, and PALBI grade in predicting 1-year survival was evaluated. CP class (AUC = 0.661) and ALBI grade (AUC = 0.653) showed better predictive values than PALBI grade (AUC = 0.617). However, PALBI grade (AUC = 0.639) showed a better overall survival (OS) than CP class (AUC = 0.615) and ALBI grade (AUC = 0.611). A similar trend was observed in the comparison between the integrated scores, with PALBI-T (AUC = 0.740) showing the best results for OS. Although the AUC of the PALBI-T score was significantly greater than that of the PALBI grade, the AUCs of the ALBI-T and JIS scores were not significantly different from that of the PALBI grade (Table 4).

| 1-Year mortality | 3-Year mortality | Overall survival | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | 95% CI | P-value† | P-value‡ | P-value§ | AUC | 95% CI | P-value† | P-value‡ | P-value§ | AUC | 95% CI | P-value† | P-value‡ | P-value§ | |

| CP class | 0.661 | 0.540–0.782 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.632 | 0.537–0.726 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.617 | 0.528–0.702 | 0.006 | 0.034 | 0.005 |

| ALBI | 0.653 | 0.532–0.774 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.63 | 0.538–0.722 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.609 | 0.522–0.699 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.008 |

| PALBI | 0.617 | 0.509–0.725 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.642 | 0.550–0.733 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.634 | 0.550–0.729 | 0.002 | 0.099 | 0.059 |

| JIS | 0.925 | 0.867–0.983 | 0.012 | 0.033 | Reference | 0.848 | 0.784–0.912 | 0.825 | 0.189 | Reference | 0.731 | 0.659–0.803 | 0.705 | 0.444 | Reference |

| ALBI-T | 0.891 | 0.817–0.965 | 0.230 | Reference | 0.033 | 0.826 | 0.759–0.894 | 0.452 | Reference | 0.189 | 0.717 | 0.642–0.791 | 0.328 | Reference | 0.444 |

| PALBI-T | 0.875 | 0.795–0.954 | Reference | 0.230 | 0.012 | 0.843 | 0.778–0.907 | Reference | 0.452 | 0.825 | 0.741 | 0.666–0.815 | Reference | 0.328 | 0.705 |

- † P-value in the table denotes comparison between the PALBI-T score and the other scores.

- ‡ P-value in the table denotes comparison between the ALBI-T score and the other scores.

- § P-value in the table denotes comparison between the JIS score and the other scores.

- ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; ALBI-T, albumin-bilirubin tumor; AUC, area under the receiver operating curve; CI, confidence interval; CP, Child–Pugh; JIS, Japan Integrated Staging; PALBI, platelet-albumin-bilirubin; PALBI-T, platelet-albumin-bilirubin tumor.

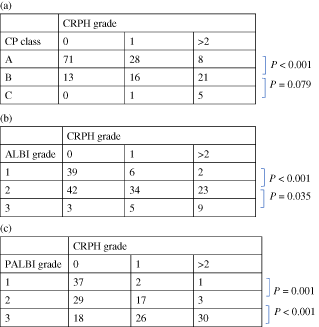

Relationship between CP class, ALBI grade, PALBI grade, and portal hypertension

There were 84 patients (51.5%) who had no evidence of PH, and 79 patients (48.4%) had at least one finding of PH. Of the patients, 45 (27.6%), 31 (19.0%), and 3 (1.8%) were CRPH grades 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The findings of PH were most stratified by the PALBI grade, whereas those stratified by the ALBI grade and CP class were almost equal (Table 5a–c).

Discussion

In this study, we compared the prognostic values of the PALBI-T score with the JIS score and ALBI-T score in alcoholic HCC. All three integrated scores contributed to the prognostic stratification of alcoholic HCC. However, the JIS score had higher AUC values than the other integrated scores in predicting 1-year survival. The PALBI-T score had higher AUC values than the other scores for OS.

Unlike other tumors, the prognosis of HCC is determined by not only the biological characteristics of the tumor24, 25 but also the function of the background liver.26, 27 Thus, both factors need to be considered in the selection of treatment.28 Thus far, various integrated scores, such those reported by Okuda et al.,29 those described in the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program,30 JIS score, and ALBI-T score, have been reported. As PH is a frequent complication of alcoholic cirrhosis, we propose a new integrated scoring system called PALBI-T score, which consists of PALBI grade and TNM stage of LCSGJ.

Regarding the AUCs for the PALBI score, ALBI-T score, and JIS score in predicting 1-year survival, the JIS score had the highest AUC (AUC = 0.925), followed by the ALBI-T score (AUC = 0.891) and the PALBI-T score (AUC = 0.875). This was consistent with the prognostic value of the CP score, ALBI grade, and PALBI grade. The predictive value of 1-year survival was considered to reflect a poor hepatic reserve function. There was no significant difference in predicting OS between the various integrated scores, but the AUC of PALBI-T was the largest.

In addition, the PALBI-T score had a significantly better prognostic value than the PALBI grade, and the ALBI-T score and JIS score were not significantly different from the PALBI grade. Elshaarawy et al.31 reported that the AUCs for the ALBI-T score at 1-year interval and the OS were 0.822 and 0.801, respectively. Hiraoka et al.9 reported that the prognostic value of the ALBI-T score was equivalent to that of the JIS score. In the present study, the AUC for the ALBI-T score at 1-year interval was 0.891, which was better than that in the previous reports. However, the AUC for the ALBI-T score for OS was inferior to the AUCs for the PALBI-T and JIS scores (AUC = 0.714, 0.740, and 0.729, respectively). This may be because most of the causes of cirrhosis in these previous reports were viral liver diseases, mainly caused by hepatitis C virus, and alcoholic cirrhosis was a minority.

This difference in the prognostic value of the integrated score due to differences in etiology may be related to PH. In fact, the portal vein pressure was higher in alcohol-related cirrhosis than in viral cirrhosis.11, 13 Moreover, the frequency of variceal bleeding was higher in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis than in patients with viral cirrhosis.11 Alcohol consumption increases portal blood flow and exacerbates PH.32 Abstinence from alcohol decreases portal pressure and halves the diameter of EV.33

There are two possible mechanisms by which PH may affect the prognosis of HCC1: reduction of hepatic reserve function, and2 possible direct effect on HCC treatment. First, PH reduces hepatic reserve function and promotes the formation of portosystemic collateral veins.34 The prevalence of collateral blood channels was reportedly higher in alcoholic cirrhosis than in viral cirrhosis.35, 36 Although portal blood flow is increased, hepatofugal flow is more common in alcoholic cirrhosis than in viral cirrhosis,37 resulting in a significantly lower hepatic tissue blood flow than in viral cirrhosis.38 Such blood flow from the portal venous system to the extrahepatic shunts reduces the hepatic reserve function in the long term.37, 39

Second, there may be a direct effect of PH on HCC treatment. PH has been reported as a prognostic factor after hepatic resection for HCC. The 5-year survival rate after hepatic resection in patients with CP class A reached 70% in the absence of PH, but the rate dropped to 20–50% in patients with PH.40 PH has also been reported as a prognostic factor after transarterial chemoembolization.22, 41 Hence, PH is closely related to the prognosis of patients with HCC, as it causes deterioration of the hepatic reserve function and affects the efficacy of HCC treatment, particularly in patients with alcohol-induced liver disease.

Although PH should always be assessed in patients with cirrhosis for prognostic stratification, universal measurement is impractical because direct measurement is invasive and requires specialized techniques. Therefore, many noninvasive surrogate methods to diagnose PH have been investigated.

CP class correlates with portal pressure regardless of whether it is compensated cirrhosis or decompensated cirrhosis.42-44 PALBI grade has also been reported as a good prognostic indicator for patients with acute variceal bleeding.15 PALBI grade appears to be of greater value in stratifying the risk for PH. This contention is supported by the fact that platelets, which are included in PALBI grade, reflect portal pressure either alone or in combination with the extent of splenomegaly.45, 46

In this study, the PALBI-T score was significantly better than the PALBI grade in predicting OS, but the AUC of the JIS score was not significantly different from that of the PALBI grade. The number of surrogate findings of PH, such as portocollateral vessels, ascites, and splenomegaly, correlated best with the PALBI grade. Taken together, the PALBI grade, which includes platelets, was thought to better reflect PH than the CP class that includes ascites, which is influenced by the albumin level. This degree of PH reflection may contribute to the favorable prognostic stratification of PALBI-T in alcoholic HCC.

This study had several limitations. The number of cases was not sufficiently large, and the work was a single-center retrospective study. In addition, it is necessary to confirm the drinking status in alcoholic cirrhosis because continued drinking is associated with the persistence and exacerbation of portal hypertension. In this retrospective study, the alcohol consumption status could not be shown. A subsequent prospective multicenter observational study is warranted.

In conclusion, in patients with alcoholic HCC, the JIS score was useful in predicting short-term prognosis, whereas the PALBI-T score appeared to be more valid in predicting OS than other integrated scores.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Edward Barroga (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8920-2607), Medical Editor and Professor of Academic Writing at St. Luke's International University, for editing the manuscript.