Mode of delivery preference in prenatal genetic counseling between English- and Spanish-speaking patients at two US medical institutions

Abstract

Although Hispanic individuals are at an increased risk for various genetic conditions, they have lower uptake of genetic counseling and genetic testing. Virtual appointments have many advantages that may help Spanish-speaking patients access genetic services more readily. Despite these benefits, there are limitations that may make them less attractive options for these individuals. This study aimed to determine if satisfaction with genetic counseling or mode of delivery preference differs between English- and Spanish-speaking individuals who have had a virtual prenatal genetic counseling session. Participants were recruited from prenatal genetic counseling clinics at Indiana University Health and Eskenazi Hospital. A REDCap survey was sent to all eligible participants. Survey questions included mode of delivery preference for future genetic counseling sessions (virtual versus in-person), the validated Genetic Counseling Satisfaction Scale, and questions inquiring about the importance of various factors affecting mode of delivery preference. Spanish-speaking individuals preferred future visits to be in-person, while English-speaking individuals preferred future visits to be virtual (Fisher's exact p = 0.003). Several factors were associated with these preferences, including waiting time, ability to leave/take off work for an appointment, length of session, childcare arrangements, and people attending the appointment (all p < 0.05). Both language groups reported similar mean satisfaction with the genetic counseling provided during their previous virtual appointments (p = 0.51). This study found that certain aspects of virtual genetic counseling appointments make them less appealing to Spanish-speaking individuals. Making virtual genetic counseling appointments more appealing while continuing to offer in-person appointments may help Spanish-speaking individuals receive necessary genetics services. Continued research into disparities and barriers to telemedicine for Spanish-speaking patients is necessary to increase access to this service delivery model for genetic counseling.

What is known about this topic

Hispanic individuals are less likely to receive genetic counseling and genetic testing compared to non-Hispanic White individuals. Virtual appointments have many advantages that may increase access to these services.

What this paper adds to the topic

Despite having had a virtual prenatal genetic counseling appointment, Spanish-speaking individuals in this study preferred future genetic counseling appointments to be in-person rather than virtual. This highlights the need for continued in-person services and directed efforts to remove barriers to virtual appointments.

1 INTRODUCTION

Hispanic individuals made up 19% of the United States' population in 2020, and this number is expected to grow to 28% by the year 2060 (https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2018/comm/hispanic-projected-pop.html). Compared to other racial and ethnic groups, Hispanic individuals are at an increased risk for various health conditions including neural tube defects and genetic conditions such as hemoglobinopathies (Flores et al., 2017; Michlitsch et al., 2009). Despite the risks affecting this ever-growing population, Hispanic individuals are underrepresented and underserved in many areas of healthcare, including genetic counseling services (Hallford et al., 2020). Studies have shown that Spanish speakers may experience the following barriers to attending medical appointments: language, health literacy, a lack of qualified interpreters, difficulty navigating the medical system, and an inability to miss work (Buckheit et al., 2017; Flower et al., 2021; Greene et al., 2019). These barriers and others may hinder much-needed genetic testing and genetic counseling services from reaching individuals of minority racial and ethnic groups (Garza et al., 2020; Jagsi et al., 2015; Lynch et al., 2017). Despite studies showing similar interest in genetics services across various racial and ethnic groups, Hispanic individuals are 35% less likely than Non-Hispanic White individuals to undergo clinical genetic testing (Carroll et al., 2020).

Previous studies have identified several advantages to virtual health appointments. In particular, virtual genetic counseling visits may offer less patient travel, better access to interpreters, shorter wait times, lower costs, improved accessibility in remote areas, and equal or greater satisfaction compared to in-person genetic counseling visits (Buchanan et al., 2015; Datta et al., 2011; Fournier et al., 2018; Hilgart et al., 2012; Mette et al., 2016; Mills et al., 2020; Uhlmann et al., 2021). Virtual appointments have become increasingly popular since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (Gorrie et al., 2021; Koonin et al., 2020). The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020 (https://www.ajmc.com/view/a-timeline-of-covid19-developments-in-2020). As people were encouraged to stay at home, the last week of March 2020 saw a 154% increase in the number of telehealth visits across the United States compared to the last week of March 2019 (Koonin et al., 2020). Since the initial spike of the pandemic, the use of telehealth has declined but remains 38 times higher than pre-COVID use (https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/telehealth-a-quarter-trillion-dollar-post-covid-19-reality). Unlike many public health events, the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting increase in telehealth appointments affected patients of all racial, ethnic, geographic, and social backgrounds. Having experienced a pandemic and a shift to telehealth as a result, Spanish-speaking individuals may be more willing to engage in virtual genetic counseling appointments.

Despite the fact that telehealth has the ability to overcome the barriers cited above and provide more equitable access to genetic services for some patients (Gorrie et al., 2021), there are notable disadvantages to virtual appointments. Although interpreters do not have to physically travel to virtual visits, many experience technical difficulties joining the virtual platform (Katzow et al., 2020; Linggonegoro et al., 2021). Patients may not have reliable access to technology or the internet, or they may not be able to successfully use an at-home specimen collection kit (Uhlmann et al., 2021). Patients could be distracted in a busy home or work environment, and pregnant patients may need to schedule a separate appointment to undergo diagnostic genetic testing in clinic (Pereira & Chung, 2020). Many studies have noted the lower uptake of telehealth services by Spanish-speaking patients. A study performed at a medical center in New York noted that several Spanish-speaking patients declined virtual genetics visits and preferred to wait for in-person visits (Pereira & Chung, 2020). A study about reproductive counseling showed that non-English-speaking patients went from having no telehealth visits before the pandemic to 4.5% of visits via telehealth during the pandemic, but these patients were still more likely to be seen in-person compared to English-speaking patients (Mann et al., 2021). Another study also documented a lower proportion of Spanish speakers utilizing telemedicine and postulated that overall access to care, health literacy, and cultural perceptions of telemedicine may explain this finding (Ramirez et al., 2021).

This is the first post-COVID-19 study to assess the thoughts of Spanish-speaking individuals who have attended virtual prenatal genetic counseling appointments. This study sought to explore mode of delivery preference (virtual vs. in-person) between English and Spanish speakers, as well as factors that affect this preference. These results may help genetic counselors and other healthcare providers better understand the needs of their Spanish-speaking patients with the goal of increasing uptake of genetic counseling by all individuals.

2 METHODS

This study was reviewed, approved, and classified as exempt by the Indiana University School of Medicine Human Subjects and Institutional Review Board (#11369). Consent was explained and obtained on the first page of the survey.

2.1 Participants and procedures

Eligible participants were 18 years of age or older and attended at least one virtual prenatal genetic counseling session through Indiana University Health or Eskenazi Hospital from March 23rd, 2020 to September 24th, 2021 as either (1) the person currently pregnant or expecting to become pregnant or (2) their partner. They must have reported their first language as English or Spanish. Patients whose first language was different from English or Spanish were excluded from the study unless their most recent genetic counseling session was conducted in English; these individuals were considered English speakers for this study. Certified interpreters were utilized during all Spanish-speaking visits that required an interpreter. Genetic counseling was provided by six certified genetic counselors of varying experience levels (range = 1–25 years, median = 9.5 years, mean = 11 years). Given that both health systems are teaching hospitals, students may have participated in sessions.

Author PDH, a native Spanish-speaker with experience translating medical terminology and developing documents in Spanish, translated the survey from English to Spanish. Author TAS determined eligible participants by performing chart reviews. Eligible participants without an email address in their medical record were unable to be contacted for the study. Email addresses and survey responses were recorded in the secure REDCap system (Harris et al., 2009, 2019). The Participant List feature was utilized to send the original email and two reminders to each eligible participant. Each email contained a personalized survey link. Individuals whose language was listed as Spanish in their medical record were sent the Spanish survey, and all others were sent the English survey. The emails were sent between August 11th and September 30th of 2021, and the survey was closed on October 1st, 2021. Participants who completed the survey were eligible to win a gift card by submitting their email address through a separate secure link. 100 participants were selected using a random number generator, and each winner received a $10 Amazon gift card via email.

2.2 Instrumentation

Demographic questions included sex, racial and ethnic background, number of children, marital status, and annual household income. We asked if participants were born in the United States, and if not, the number of years lived in the United States; however, they were not required to answer this question and other potentially sensitive demographic questions. Participants were asked if their most recent visit was their first prenatal genetic counseling appointment, what type of technology was utilized (videoconference or telephone), and the primary reason for the appointment. They were also asked what type of transportation they typically use to travel to an in-person medical appointment.

We utilized the Genetic Counseling Satisfaction Scale (GCSS), a validated tool that measures patient satisfaction with genetic counseling appointments (Tercyak et al., 2001). The scale consists of six statements to assess if patients feel their genetic counselor understood and cared about them, as well as whether the appointment was valuable and the right length of time for their needs (Tercyak et al., 2001). Participants could respond using a four-point Likert scale, which ranged from 1 = strongly agree, 2 = somewhat agree, 3 = somewhat disagree, and 4 = strongly disagree. Scores were coded and summed across the six statements so that high values reflect high satisfaction, and low values reflect low satisfaction. Scores could range from 6 to 24.

A 19-item matrix was developed to explore opinions about factors that may affect mode of delivery preference. Factors included childcare arrangements, COVID-19-related concerns, transportation access/use, quality of care, waiting time and more. A complete list is provided in the Supporting Information. For each factor, two statements were provided: one that supported the preference of in-person appointments, and one that supported the preference of virtual appointments. “Not Applicable” was an option for certain factors. Participants were instructed to select one of the two statements for each factor. For each item in the matrix, a value of +1 was coded for each response that supported the preference of virtual appointments, −1 for the preference of in-person appointments, and 0 for N/A. The values of the 19 responses were summed to construct a virtual preference score. A positive virtual preference score signified a preference towards virtual appointments, and a negative score signified a preference towards in-person appointments. Participants were also asked whether they would prefer a virtual or in-person prenatal genetic counseling session in the future, and their answers were compared to their virtual preference scores. Participants then ranked the top five factors that most influenced their mode of delivery preference. The full survey can be found in the Supporting Information.

2.3 Data analysis

Association between categorical variables was evaluated using a Fisher's exact test, including association of language with (1) mode of delivery preference for a future visit, (2) each of the 19 factors relating to mode of delivery preference (excluding N/A responses), and (3) mode of transportation. Due to the small numbers of patients choosing “I use a ride share service,” “A friend drives me,” and “other,” responses to these options were combined and compared to “I drive myself.” For each factor, effect size was calculated using Cramer's V. Quantitative variables such as age, were compared between the two language groups using the Student t-test. Because the GCSS and the virtual preference scores were skewed, a nonparametric Wilcoxon test was utilized to compare scores between qualitative variables with two categories such a language, and mode of delivery preference, and Kruskal-Wallis for qualitative variables with three or more categories (e.g., education, factor most influential on preference). Variables such as education and race/ethnicity were recoded to combine responses due to small numbers across all potential response categories (Table 1). We examined if language, education, or the most influential factor affecting mode of delivery preference predicted the virtual preference scores using nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon or Kruskal-Wallis). Several participants selected one of the following factors as being the “most influential” in the preference for mode of delivery: quality of care, severity of the diagnosis, taking off work, childcare, COVID concerns, distance. Due to small numbers for the remaining factors, they were combined into “other”. Spearman rank correlation was employed to examine the relationship between GCSS and virtual preference scores. Significant (p < 0.05) variables were then included into one analysis of variance (ANOVA) model to account for all variables simultaneously. Mean preference scores and standard errors (SE) for variables included in the model, after adjustment for all variables in the ANOVA model are reported. Similarly, p-values based on the type II sum of squares are provided, to demonstrate the contribution of the variable after accounting for other variables in the model. SAS version 9.4 was employed in all statistical analyses.

| Englisha N = 166% (N) | Spanisha N = 17% (N) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | ||

| White Non-Hispanic | 75.3% (125) | 0% (0) | |

| Black | 10.2% (17) | 0% (0) | |

| White Hispanic | 3% (5) | 50% (8) | |

| Asian | 6% (10) | 0% (0) | |

| More than one race | 4.2% (7) | 12.5% (2) | |

| Other | 1.2% (2) | 37.5% (6) | |

| Age | 0.98 | ||

| 18–25 | 13.9% (23) | 18.8% (3) | |

| 26–30 | 25.9% (43) | 12.5% (2) | |

| 31–35 | 24.7% (41) | 25.0% (4) | |

| 36–40 | 28.3% (47) | 37.5% (6) | |

| 40+ | 7.2% (12) | 6.3% (1) | |

| Gender | 1 | ||

| Female | 97.6% (162) | 93.8% (15) | |

| Male | 1.8% (3) | 0% (0) | |

| Other/Prefer not to answer | 0.6% (1) | 6.3% (1) | |

| Education | <0.001 | ||

| No high school diploma or GED equivalent | 1.2% (2) | 25% (4) | |

| High school diploma or GED equivalent | 8.4% (14) | 43.8% (7) | |

| Some college | 10.2% (17) | 6.3% (1) | |

| Bachelor's/Associate's degree | 45.8% (76) | 25% (4) | |

| Degree beyond Bachelor's | 34.3% (57) | 0% (0) | |

| Marital status | 0.16 | ||

| Single | 13.9% (23) | 31.3% (5) | |

| Married or living with a partner | 84.3% (140) | 68.8% (11) | |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 1.8% (3) | 0% (0) | |

| Household Income | <0.001 | ||

| <$1000 | 3.6% (6) | 31.3% (5) | |

| $1000–$29,000 | 9.6% (16) | 37.5% (6) | |

| $30,000–$59,000 | 14.5% (24) | 18.8% (3) | |

| $60,000–$89,000 | 13.3% (22) | 0% (0) | |

| $90,000+ | 52.4% (87) | 0% (0) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 6.6% (11) | 18.8% (3) | |

| Born in the United States | N/A | ||

| Yes | 84.8% (140) | 0% (0) | |

| No | 15.2% (25) | 100% (16) | |

| If not, years lived in the United States | 0.077 | ||

| 1–4 | 36% (9) | 56.3% (9) | |

| 5–9 | 24% (6) | 25% (4) | |

| 10+ | 40% (10) | 18.8% (3) | |

| Time since appointment | 0.42 | ||

| 0–6 months | 20.2% (33) | 31.3% (5) | |

| 7–12 months | 36.8% (60) | 25% (4) | |

| >12 months | 42.9% (70) | 43.8% (7) | |

| Reason for the appointmentb | |||

| Family history of a genetic condition | 33.7% (56) | 29.4% (5) | 0.79 |

| Abnormal blood test, diagnostic test, or ultrasound finding | 19.3% (32) | 29.4% (5) | 0.34 |

| Prepregnancy counseling or carrier screening | 30.1% (50) | 5.9% (1) | N/A |

| Advanced maternal age (>35 years old) | 38% (63) | 23.5% (4) | 0.30 |

| I do not know | 3.6% (6) | 11.8% (2) | N/A |

| Other | 10.2% (17) | 5.9% (1) | N/A |

| Living children at the time of the appointment | 0.008 | ||

| 0 | 51.2% (85) | 18.8% (3) | |

| 1–2 | 45.2% (75) | 62.5% (10) | |

| 3–4 | 3.6% (6) | 12.5% (2) | |

| 5+ | 0% (0) | 6.3% (1) | |

| Technology used to conduct the appointment | 0.004 | ||

| Videoconference | 96.9% (155) | 73.3% (11) | |

| Telephone | 3.1% (5) | 26.6% (4) | |

| Was this your first genetic counseling appointment? | 0.74 | ||

| Yes | 82.9% (136) | 81.3% (13) | |

| No | 17.1% (28) | 18.8% (3) | |

| Transportation for medical appointments | <0.001 | ||

| I drive myself in my car | 97.6% (162) | 43.8% (7) | |

| A friend drives me | 0.6% (1) | 43.8% (7) | |

| I use a ride share service | 0.6% (1) | 12.5% (2) | |

| Other | 1.2% (2) | 0% (0) | |

- Note: p-Value is reported from the Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and Student t-test for quantitative variables. p-Values represent comparisons between English- and Spanish-speaking participants. Bolded values indicate p-values < 0.05.

- Abbreviations: GED, General Educational Development; N/A, Not Applicable.

- a Primary language is defined as self-reported primary language OR English if a participant spoke a language other than English or Spanish, but their most recent appointment was conducted in English. Other languages reported were Arabic (1), Oruko mi ni tope (1), Chinese (1), French (1), and Portuguese (1).

- b Participants could select more than one, percentages do not sum to 100%.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographics

789 English-speaking and 85 Spanish-speaking participants met inclusion criteria for the study. The response rate for English-speaking participants was 21% (n = 166), similar to the response rate of 20% (n = 17) for Spanish-speaking participants. As shown in Table 1, English speakers had significantly more education and higher income than Spanish speakers (both Fisher's exact p < 0.001), and they were more likely to drive themselves to an appointment (97%) compared to Spanish speakers (44%, Fisher's exact p < 0.001). 15.2% of English speakers were born outside of the United States (US) compared to 100% of Spanish speakers. English-speaking participants who were not born in the United States lived in the United States for slightly, but not significantly more time (mean = 7.0 years, SE = 0.65) than Spanish-speaking participants who were not born in the United States (mean = 5.2 years, SE = 0.73; t(39) = 1.82, p = 0.077). Spanish speakers were more likely than English speakers to have telephone visits (Fisher's exact p = 0.004).

3.2 Patient satisfaction with virtual genetic counseling session

There was no difference in mean GCSS scores between the two language groups (Table 2; Wilcoxon p = 0.51). The estimated effect size of the difference in mean GCSS scores was 0.11 (considered a small effect size), and the post-hoc power to detect this effect with the study's sample size was <10%. Regardless of language, participants who preferred virtual genetic counseling visits had slightly higher GCSS scores than those who preferred in-person appointments (Table 2; Wilcoxon p = 0.046).

| GCSS scores | Virtual preference scores | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = # | Mean (SE) | Median | Wilcoxon p-value | N = # | Mean (SE) | Median | Wilcoxon p-value | |

| Language | 0.51 | 0.005 | ||||||

| English | 163 | 21.67 (0.29) | 24 | 161 | 2.70 (0.46) | 4 | ||

| Spanish | 15 | 21.27 (0.92) | 23 | 15 | −2.67 (2.0) | −6 | ||

| Mode of delivery preference | 0.046 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Virtual | 114 | 22.14 (0.30) | 24 | 114 | 5.23 (0.42) | 5.5 | ||

| In-person | 62 | 20.82 (0.53) | 23 | 62 | −3.24 (0.62) | −3.5 | ||

- Note: The bolded entries indicate p-values <0.05.

- Abbreviations: GCSS, Genetic counseling satisfaction scale; SE, standard error.

3.3 Mode of delivery preference

Spanish-speaking participants were more likely to prefer a future genetic counseling appointment to be in-person (73%) compared to English-speaking participants (32%), who were more likely to prefer a virtual appointment (Fisher's exact p = 0.003). This was reflected in the virtual preference scores, where English speakers had significantly higher virtual preference scores (Table 2). Overall, participants who preferred virtual visits had significantly higher virtual preference scores compared to participants who preferred in-person visits (Table 2). Spanish-speaking individuals who believed using an interpreter virtually would be easier were also more likely to prefer virtual visits (Fisher's exact p = 0.025).

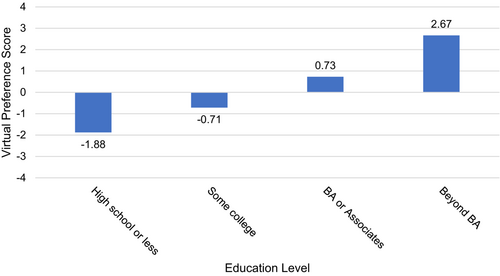

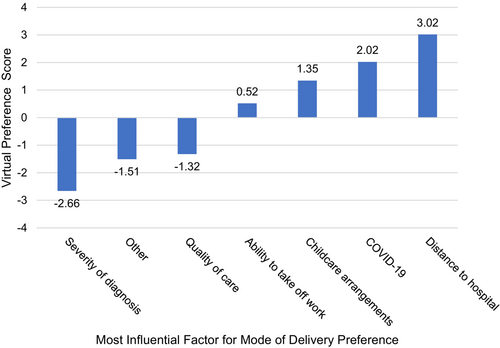

Variables identified above that were significantly (p < 0.05) associated with the preference score (language, GCSS total score, most influential factor, education, age) were included in one ANOVA model. These results revealed that after accounting for all variables, there was a main effect of language (F(1,154) = 4.68, p = 0.032). Specifically, English-speaking participants preferred virtual appointments (mean = 2.32, SE = 0.59) compared to Spanish-speaking participants, who preferred in-person appointments (mean = −1.91, SE = 1.88). Regardless of language, the most significant predictor of the virtual preference score was the GCSS score (F(1,154) = 7.88, p = 0.006), in that higher satisfaction was associated with higher virtual preference score (rho = 0.17). There was also a main effect of education (F(3,154) = 3.51, p = 0.017; Figure 1) such that individuals with more education preferred virtual genetic counseling appointments (those with BA or more mean = 2.67, SE = 0.125) compared to individuals with less education (those with high school diploma or less mean = −1.88, SE = 1.40). Patients who indicated that severity of diagnosis was the most influential factor in their preference for mode of delivery had the lowest virtual preference scores, (mean = −2.66, SE = 1.41) compared to patients who indicated distance (mean = 3.02, SE = 1.95) or COVID-19 (mean = 2.02, SE = 1.70) was the most influential (F(6,154) = 2.57, p = 0.021; Figure 2).

3.4 Factors affecting mode of delivery preference

We examined the 19 individual components of the virtual preference score to explore which factors differed between English- and Spanish-speaking participants (Table 3). Compared to Spanish speakers, English speakers were significantly more likely to choose the virtual statement for the following factors: waiting time (p < 0.001), ability to leave/take off work for an appointment (p < 0.001), length of session (p = 0.010), childcare arrangements (p = 0.016), and people allowed/able to attend the appointment (p = 0.023). The effect size was moderate for these five factors, with Cramer's V ranging from 0.25 to 0.21.

| % English speakers who chose the virtual statement | % Spanish speakers who chose the virtual statement | Fisher's exact p-value | Effect size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waiting time | 92% (148/161) | 47% (7/15) | <0.001 | 0.24 |

| Ability to leave/take off work for an appointmenta | 80% (101/126) | 33% (3/9) | 0.005 | 0.25 |

| Length of session | 68% (110/161) | 33% (5/15) | 0.010 | 0.21 |

| Childcare arrangementsa | 79% (86/109) | 46% (6/13) | 0.016 | 0.23 |

| People attending the appointmenta | 83% (118/142) | 50% (5/10) | 0.023 | 0.21 |

| Transportation use | 2% (3/159) | 14% (2/14) | 0.053 | 0.20 |

| Costa | 92% (79/86) | 73% (8/11) | 0.084 | 0.20 |

| Access to internet/cell phone service | 100% (161/161) | 93% (14/15) | 0.085 | 0.25 |

| Technology access | 100% (161/161) | 93% (14/15) | 0.085 | 0.25 |

| Distance to the hospital | 35% (57/161) | 13% (2/15) | 0.095 | 0.13 |

| Preferred location | 54% (87/161) | 33% (5/15) | 0.18 | 0.12 |

| Family obligationsa | 87% (88/101) | 73% (11/15) | 0.23 | 0.13 |

| Transportation access | 1% (2/161) | 7% (1/15) | 0.24 | 0.12 |

| Quality of care | 31% (50/161) | 13% (2/15) | 0.24 | 0.11 |

| Severity of diagnosisa | 10% (15/148) | 0% (0/15) | 0.36 | 0.10 |

| COVID-19 | 38% (61/161) | 27% (4/15) | 0.58 | 0.06 |

| Ease of using an interpretera | 45% (5/11) | 33% (5/15) | 0.69 | 0.12 |

| Confidentiality | 34% (55/161) | 33% (5/15) | 1 | 0.05 |

| Technology use | 98% (157/161) | 100% (14/14) | 1 | 0 |

- Note: Rows are ordered by Fisher's exact p-value comparing languages for each virtual statement by smallest to largest p-value. The higher percentage in each row is bolded when p < 0.05. Effect size was calculated using Cramer's V. Remaining percentages represent participants who selected the in-person statement or N/A. See Supporting Information for breakdown of in-person and N/A responses for each factor. Bolded values indicate Fisher's exact p-values <0.05.

- a p-value and percent calculated without N/A responses.

4 DISCUSSION

These results demonstrate that Spanish-speaking participants who previously attended a virtual prenatal genetic counseling appointment were more likely to prefer future genetic counseling appointments to be in-person, whereas English-speaking participants who previously attended a virtual prenatal genetic counseling appointment were more likely to prefer future appointments to be virtual. This conclusion was determined via two measures—stated preference and a summary score constructed from 19 different factors. These results support previous studies that showed Spanish speakers prefer in-person appointments (Pereira & Chung, 2020; Ramirez et al., 2021). There could be numerous explanations for this finding. Most Spanish speakers in this study felt that using an interpreter would be easier in-person, which could lead to an in-person preference. They were also more likely than English speakers to have a telephone visit rather than a video visit, and this prior experience could possibly affect mode of delivery preference. However, several studies have shown no difference in patient satisfaction between telephone and video visits (Allen et al., 2021; Lawford et al., 2022; Mustafa et al., 2021). Knowing that Hispanic individuals underutilize genetic counseling and genetic testing (Jagsi et al., 2015; Lynch et al., 2017), genetic counselors and other healthcare providers can use the results from this study to tailor their outreach plans to best serve these individuals. Healthcare providers can make their services more accessible to Spanish-speaking individuals by continuing to offer in-person appointments even as telehealth options increase. Furthermore, they may note the factors associated with lower virtual preference scores and take action to reduce any real or perceived barriers to virtual appointments.

Several variables were found to be associated with the virtual preference score, with the most significant being GCSS score. Increased satisfaction with a prior virtual prenatal genetic counseling appointment was associated with an increased desire for virtual genetic counseling appointments in the future. Individuals with more education were also more likely to prefer virtual appointments. Similar trends have been noted before; one study found that individuals with less education were less likely to use the internet to look for a health care provider (Kontos et al., 2014). Additionally, most participants in this study preferred to have an in-person appointment if the fetal diagnosis was severe, and they believed they would get better quality of care at an in-person appointment. This aligns with other studies showing that patients highly value perceived quality of care (Polinski et al., 2016) and are opposed to receiving bad news via telemedicine (McCabe et al., 2021).

Interestingly, the factor with the greatest difference between English- and Spanish speakers was waiting time. Almost all English speakers felt they would have a shorter wait time at a virtual visit than an in-person visit compared to approximately half of Spanish speakers. This trend may be explained by how time is perceived in Hispanic culture. Sue and colleagues suggest that time construct of Hispanic and Latino individuals follows a past–present orientation, which places greater value around family, respeto for the individuals in authority, older generations and ancestors, and personalismo (Sue et al., 2019). To note, respeto is a cultural construct where authority and hierarchy are recognized (Añez et al., 2005). In addition, personalismo emphasizes the development of personal relationships and connections (Juckett, 2013). Therefore, perception of wait time may be perceived differently informed by what holds greater value, that is, time spent in waiting versus the personal interaction from a face-to-face visit. The in-person interaction allows for a connection with the provider, which circles back to the present-time (in the now) time construct that many Hispanic individuals favor, as indicated by the result that Spanish-speaking patients in this study had lower virtual preference scores than English-speaking patients. It is important to note that there is limited research describing the construct of time across cultures and how differences in perception of time associates with healthcare preferences. Understanding these differences and their relationship to healthcare choices could help to improve health-related outcomes in non-White populations.

A slight majority of English speakers believed it would be easier to leave or take off work for virtual visits compared to less than a quarter of Spanish speakers. While studies have shown that virtual visits can eliminate travel time (Hilgart et al., 2012; Mills et al., 2020), employees may still have to leave work to travel home for a virtual appointment, especially if they do not have a private office at their workplace or cannot work from home. Hispanic or Latino workers are less likely to work from home and have a flexible work schedule compared to other workers (https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/flex2.pdf).

Only one-third of Spanish-speaking participants felt it would be easier to use an interpreter during a virtual visit compared to an in-person visit. Although travel is eliminated with virtual visits, many interpreters experience technical difficulties joining the virtual platform (Katzow et al., 2020; Linggonegoro et al., 2021; Wilhite et al., 2021). Even if interpreters are able to join the visit, individuals on the call may talk over each other, and it can be difficult to understand the patient's concerns (Wilhite et al., 2021). Our study did not specifically assess for satisfaction with a virtual interpreter, but patients' prior experiences with a virtual interpreter may have contributed to their mode of delivery preference. Most English speakers felt they would have the right amount of time to discuss their concerns at a virtual appointment compared to just one-third of Spanish speakers. Several studies recommend that providers set aside extra time to meet with non-English-speaking patients to facilitate patient understanding and to make up for time spent interpreting (Juckett, 2013; Turner & Madi, 2019).

Although Spanish speakers overall preferred an in-person appointment, more than half relied on a friend or a ride share service. Despite transportation being less accessible for the Spanish speakers in this study, they still preferred to have in-person appointment in the future. Even though virtual visits may remove the transportation barrier, this study identified other factors that may be more significantly hindering Spanish-speaking individuals from preferring virtual appointments.

Overall, participants who reported greater satisfaction were more likely to prefer virtual genetic counseling visits in the future. Despite English speakers preferring virtual visits in the future, there was no difference in satisfaction of a prior virtual visit when comparing English- and Spanish-speaking patients. Had we detected a difference in satisfaction scores, it might have implicated that Spanish speakers' preference of in-person visits may in part be explained by their dissatisfaction with a prior virtual visit when compared to English speakers. Although the sample size was not powered to detect small effect sizes, the small effect size suggests that there was no substantially meaningful difference in satisfaction with the previous virtual prenatal genetic counseling session between these two groups.

Despite the groups having similar satisfaction with a virtual visit, Spanish speakers continue to prefer in-person visits. A possible explanation for this trend could be the Latine cultural value of personalismo. For example, warm conversations between healthcare providers and Latine individuals can help build confianza (trust). This is facilitated by both the manner in which they talk to each other as well as the physical distance between them (https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/culturalcompetence/servicesforhispanics.pdf). Further research may be necessary to inform the effects of personalismo on mode of delivery preference for medical appointments among Latine individuals.

4.1 Study limitations

This study has several limitations. Our sample size for Spanish-speaking participants was small, though the response rate was similar to that of the English-speaking participants. Likewise, the percentage of Hispanic individuals in our study (9.3%) was proportional to the Hispanic population in Indiana (7.3%; https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/IN). It is also important to note that there are many aspects to culture besides language, and these findings are not meant to define all Spanish speakers. We recognize the microculture that exists across each Latin American country as well as across other ethnic minorities, and it is our hope to showcase a fraction of those results. Another limitation of the study is that all participants received prenatal genetic counseling through two teaching hospitals that may have involved students. Some participants expressed via free text responses that they would have chosen N/A or “No Preference” for questions that did not provide it as an option. Including a “No Preference” option for all factors would have created a more consistent scale. Lastly, the survey was provided via email, which implies that participants have the technology to attend virtual appointments. This study should be followed by further research that address these limitations. In particular, qualitative research may provide insight into the trends noted in this study.

4.2 Practice implications

We encourage genetic counselors and other healthcare providers to recognize that Spanish speakers in this study showed a preference for in-person appointments. Healthcare providers may consider how their clinics can improve efforts to serve the Spanish-speaking community, especially as the use of telehealth remains increased due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Continuing to offer in-person appointments and working to eliminate any real or perceived barriers may help Spanish-speaking individuals receive proper care. Knowing that satisfaction with a prior virtual visit was associated with greater preference for virtual visits in the future, healthcare providers can use the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to give patients a positive experience with telemedicine. This may improve patients' perceptions of virtual visits going forward.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study was the first to directly compare English- and Spanish-speaking individuals' preferences between virtual and in-person genetic counseling appointments after attending at least one virtual appointment. Spanish speakers preferred in-person visits despite experiencing a virtual appointment, and English speakers preferred virtual visits. Satisfaction with a virtual prenatal genetic counseling visit was similar between the two groups, but overall, those who reported greater satisfaction were more likely to prefer virtual visits in the future. Spanish speakers did not show a preference towards any virtual preference statements compared to English speakers, indicating that they have unique barriers to virtual appointments. Further research should investigate these potential barriers in a larger sample of Spanish speakers as well as other racial and ethnic minority groups.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Authors Taylor A. Steyer and Leah Wetherill confirm that they had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors gave final approval of this version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The terms Hispanic, Latine, and Spanish-speaking are utilized in this study. We wish to recognize that these terms bring different sentiments to individuals of that background. This study focused on individuals who speak Spanish, so the term Spanish-speaking most often used in this paper. Since some of the cited literature uses the term Hispanic, this is reflected in our citations of those papers. Latine refers to cultural values held by those who may identify as Hispanic, Spanish-speaking, and/or Latine. This research was supported by the Department of Medical and Molecular Genetics at the Indiana University School of Medicine as well as the National Society of Genetic Counselors Prenatal Special Interest Group. The team would like to thank all participants for their time and willingness to participate in the study. The research presented in this paper was conducted to fulfill a degree requirement of first author Taylor A. Steyer.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Authors Taylor A. Steyer, Priscila D. Hodges, Caroline E. Rouse, Wilfredo Torres-Martinez, Leah Wetherill, and Karrie A. Hines declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

HUMAN STUDIES AND INFORMED CONSENT

This study was reviewed and approved by the Indiana University Human Research Protection Program (#11369). Details of consent were explained on the first page of the survey materials. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

ANIMAL STUDIES

No nonhuman animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data collected for this study are not currently available through a publicly available repository but are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.