How do geneticists and prospective parents interpret and negotiate an uncertain prenatal genetic result? An analysis of clinical interactions

Abstract

Variants of unknown significance (VUS) and susceptibility loci (SL) are a challenge in prenatal genetic counseling. The aim of this study was to explore how such uncertain genetic results are communicated, negotiated, and made meaningful by genetics healthcare providers and couples in the actual clinical setting where results are delivered. The study was based on an anthropological approach and the material consisted of observations and audio-recordings from 16 purposively sampled genetic counseling sessions where prenatal testing had identified an inherited or de novo VUS or SL result. Field notes and transcripts from audio-recordings were analyzed using thematic analysis. The analysis identified a number of specific interpretations and strategies that clinical geneticists and couples collectively used for dealing with the ambiguity of the result. Thus, the analysis resulted in a total of three themes, each with 3–4 subthemes. The theme ‘Setting the scene’ describes the three-stage structure of the consultation. The theme ‘Dealing with uncertainty’ includes ‘normalizing strategies’ that emphasized the inherent uncertainty in human life in general and ‘contextualizing strategies’ that placed the result in relation to the surrounding society, where technological developments lead to new and unforeseen challenges. The theme ‘Regaining control’ includes interpretations that made the knowledge useful by focusing on the value of being prepared for potential, future challenges. Other strategies were to book an extra scan—to reconfirm fetal structural health and to reconnect to the pregnancy. Finally, inquiring about the sex was clearly a way for the couple to signal their investment in the pregnancy. Based on the analysis, we propose that these interpretations served to transform and reduce ambiguity through a process of reconfiguring the biomedical information into knowledge that resonated with the couples' lifeworlds. In this process, both geneticist and couples drew on wider social and moral concerns about uncertainty and responsibility.

1 INTRODUCTION

Chromosomal microarray (CMA) detects copy number variants (CNVs) including chromosomal microdeletions and microduplications associated with a variety of cognitive disorders, congenital anomalies, and predispositions to neurodevelopmental conditions (Wapner et al., 2012). In Denmark, CMA's increased yield over traditional karyotyping was the main reason for introducing CMA as a first-tier test following a high-risk prenatal screening result and/or the detection of an ultrasound anomaly. The increased diagnostic yield, however, is accompanied by the identification of variants of unknown significance (VUS), or of incomplete penetrance and/or variable expressivity (susceptibility loci (SL)). From a genetics perspective, there is a difference between CNVs that are known but variable (SL), and CNVs that have never been reported before (VUS), however, both types present prospective parents with potential ambiguity and uncertainty regarding the future for their unborn child. Thus, in the following, we refer collectively to SL and VUS results as ‘ambiguous CNV results’.

Ambiguous CNV results can be a challenge in the counseling setting (Walser, Werner-Lin, Russell, Wapner, & Bernhardt, 2016; Werner-Lin, McCoyd, & Bernhardt, 2016) because they can be difficult to both communicate and to understand (Rubel, Werner-Lin, Barg, & Bernhardt, 2017; Walser, Kellom, Palmer, & Bernhardt, 2015). Uncertainty in the prenatal setting is particularly challenging because many parents enter into prenatal testing hoping for reassurance of a healthy baby (Lou et al., 2017; Oyen & Aune, 2016). Studies have found that pregnant women often want maximal information about their unborn child (Hartwig, Miltoft, Malmgren, Tabor, & Jørgensen, 2019; van der Steen et al., 2015; Walser et al., 2015), but may be unprepared for the scope and complexity of such information (Bernhardt et al., 2013; Riedijk et al., 2014). The difficulty in robustly correlating VUS results with phenotypic outcomes, or in predicting how affected a child will be by an SL result, complicate both understanding and decision-making for couples trying to decide what the results mean to them and what the consequences should be (Riedijk et al., 2014; Rubel et al., 2017). For example, prospective parents have reported feeling anxious and overwhelmed after receiving a VUS result and that the uncertain and unquantifiable risks were ‘toxic knowledge’ that caused lingering worry about their child's development (Bernhardt et al., 2013). In contrast, another study found that parents felt shock and an initial worry following an SL result, but most had no enduring worries (van der Steen et al., 2016). Studies have also shown how parents actively engage in interpretation of results to relieve anxiety, manage uncertainty, and establish normalcy in pregnancy (Rubel et al., 2017; Werner-Lin, Barg, et al., 2016).

Ambiguous CNV results are also a challenge to genetics healthcare providers. In an interview study (Bernhardt, Kellom, Barbarese, Faucett, & Wapner, 2014), genetic counselors identified a number of challenges when providing counseling on an uncertain result, for example, lack of numerical probability, uncertainty of phenotype, lack of information on prognosis, role conflict (expected to be expert), and perceived distress for patients. The authors suggest that under these conditions of uncertainty, the genetics healthcare provider and the client must engage in a deliberative and mutual process of problem-solving.

Ambiguous CNV results expose the uncertainties and limitations of genetic expert knowledge (Fox, 1980) and leave space open for interpretation and negotiation of the meaning and potential consequences of the result (Walser et al., 2017; Werner-Lin, McCoyd, et al., 2016). There is a growing body of social science literature on the complex ways in which genetic expert knowledge, particularly genetic risk, is interpreted and appropriated in peoples' everyday lives (Atkinson, Featherstone, & Gregory, 2013). A central contribution of these studies is a move beyond the traditional distinction between expert and lay knowledge to show more complex understandings of how genetic knowledge is re-appropriated and made relevant (or irrelevant) in specific social and cultural context (see, e.g., Cox & McKellin, 1999; Svendsen, 2005). This complex re-appropriation starts in the clinical encounter. The theoretical approach underpinning this study draws on anthropological perspectives on biomedical knowledge as produced and reproduced by the actions and interactions of both healthcare providers and patients (Lou, Nielsen, Hvidman, Petersen, & Risor, 2016; Mattingly, 2008). Rather than approaching clinical encounters as an exchange of information between expert and layman, the analytical approach of the present study has been to analyze clinical encounters as a collective and formative process of knowledge production where the ambiguous CNV result is negotiated and made meaningful through interaction. In this process, the parties rely not only on biomedical information and experiential knowledge but also—as the results will show—on broader social and moral concerns.

Several questionnaire and interview studies of genetics healthcare providers' and patients' perspectives have provided valuable insights into how both parties experience genetic counseling sessions retrospectively (Bernhardt et al., 2014; Hillman, Skelton, Quinlan-Jones, Wilson, & Kilby, 2013; Joosten et al., 2016; Menezes, Hodgson, Sahhar, & Metcalfe, 2013; Shkedi-Rafid, Fenwick, Dheensa, Wellesley, & Lucassen, 2016; Walser et al., 2016). A few studies have investigated clinical interaction, particularly regarding the decision to test (Aalf, Oor, de Haes, Lescho, & Smets, 2007; Hodgson, Gillam, Sahhar, & Metcalfe, 2010). However, there is a paucity of research on the actual delivery of prenatal genetic results. Such knowledge is central for further improvement of genetic counseling in a professional space that is defined by increasing demand and complexity. Thus, the aim of this study was to explore how ambiguous CNV results are negotiated and made meaningful by genetics healthcare providers and couples in the actual clinical settings where the results are delivered.

2 METHODS

The present study is one of three qualitative studies in a research project that aims to explore the social construction of genetic knowledge. To answer the present research questions, an explorative, ethnographic approach was used through a combination of fieldwork, observations, and recordings of consultations (Hammersley & Atkinson, 2007). Furthermore, follow-up interviews were conducted with couples who had received an uncertain genetic result. However, the present analysis is based only on observations and recordings of consultations.

2.1 Setting

In Denmark, all pregnant women are offered a free and tax-financed prenatal care including combined first-trimester screening for chromosomal aberrations. Participation is high (>90%) (National database of fetal medicine, 2016), and in case of a high-risk result, the pregnant woman is offered noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) or invasive diagnostics (chorionic villus sample or amniocentesis). In Denmark, the majority of high-risk women choose invasive diagnostics over NIPT (Hartwig et al., 2019), and the invasive sample is analyzed using CMA.

Prior to the invasive procedure, the women receive information from an obstetrician or a fetal medicine specialist. This information addresses the small, procedure-related risk of miscarriage (<1%) and an explanation of the type of results the CMA can provide, including the risk of an uncertain or unexpected result. All analyses are performed at the university hospital in the region and all interpretations are performed by clinical geneticists. In case a VUS or SL result, a blood sample is taken from the parents for comparison. The final result and interpretation are then sent to the obstetric department who deliver the result by phone. Results are usually available within a week. If relevant, the calling obstetrician will refer the couple to genetic counseling at the university hospital, for example, in cases of an SL or VUS result. In these cases, the prenatal genetic counseling is always performed by a clinical genetics fellow or senior resident (from hereon referred to as geneticists). The geneticists can refer patients to further counseling or ultrasound examination, or they can assist the couple in applying for a termination of pregnancy (TOP). In Denmark, TOP is legal up to and including 12 gestational weeks and allowed on approval by a specialist board up to and including 22 gestational weeks. In most cases, a TOP application based on a CNV result will be approved.

2.2 Procedures

- Women and couples who were or had been pregnant and where CMA analysis had detected an inherited or de novo ambiguous CNV result.

- Cases where a parental CNV had been known prior to the pregnancy (n = 8) and thus was not new knowledge to the couple.

- Cases of a de novo prenatal CNV where the couple chose TOP (n = 5). In three of these cases, the fetus also had severe malformations not explained by the CNV result. These cases were excluded as we estimated that the ambiguous genetic result would have less of a lasting impact on the couples' subsequent lives.

- Ethical considerations (n = 2)

One couple declined participation and the final sample thus consisted of 16 consultations.

Prior to the consultation, the couples were given written and oral information about the research by the first author, and upon consent, the consultation was observed and digitally recorded, while notes on the setting and interaction were taken (e.g., emotional outbursts or use of devices). In three cases, the consultation was not recorded due to ethical concerns (e.g., couple being a little confused or an estimated overload of information prior to consultation), but in these cases, extensive notes were taken during and immediately after the consultation. Following the consultation, basic demographic information was obtained. Recordings were deleted if the couple did not meet inclusion criteria (15 consultations) or declined participation (one consultation). Characteristics of included couples and counseling sessions are presented in Table 1.

| Age | |

| Maternal age average | 30 (range: 24–40) years |

| Paternal age average | 31 (range 25–41) years |

| Educational levela | |

| High | 10 |

| Medium | 18 |

| Low | 4 |

| Parity | |

| 0 | 9 |

| 1 | 3 |

| 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 2 |

| CNV result | |

| Inherited SL | 9 |

| De novo SL | 1 |

| Inherited VUS | 3 |

| De novo VUS | 2 |

| Inherited SL, de novo VUS | 1 |

| Gestational age | |

| 1. trimester | 3 |

| 2. trimester | 7 |

| 3. trimester | 2 |

| No longer pregnant | 4 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Danish | 32 |

| Other | 0 |

| Duration of consultation | |

| Average duration | 41 min |

| Range | 23–82 min |

- Abbreviations: CNV, copy number variant; SL, susceptibility loci; VUS, variant of unknown significance.

- a Using the education nomenclature (ISCED) from Statistics Denmark, educational level was grouped into three categories: low (1–10 years), medium (11–14 years), and high (>15 years). Students are categorized by their next educational level.

2.3 Data analysis

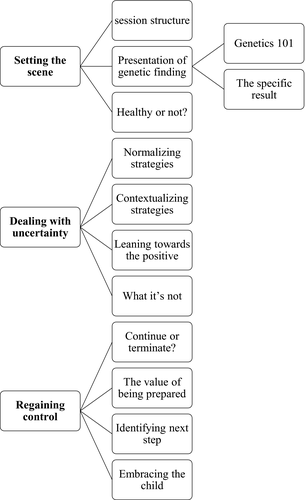

During the study period, recorded consultations were continually transcribed verbatim by a research assistant. Notes from observations were added to the transcripts where relevant. Transcripts and notes from unrecorded consultations were analytically treated as ethnographic field notes and analyzed using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The processes of analysis included on-going reading and rereading of written material during the study period until information power (Malterud, Siersma, & Guassora, 2015) was estimated to be adequate and data collection ceased. The first step in the final analysis of total material was an open coding—using a mix of inductive (bottom-up) and deductive (top-down) codes. All transcripts were read and open coded by SL to generate a list of preliminary codes. These preliminary codes were then discussed with the co-authors, and after critical consideration, an initial grouping and ordering of codes (inductive and deductive together) was performed. The second step consisted of a more focused coding, where the specific definition and content of each code (including when to use and when not to use) was further developed and described in a codebook to secure a consistent, final coding. On the basis of this, and after discussions with co-authors, the final codes were settled and the material was coded by the first author using NVivo 10 software (QSR International). A further analysis consisted of investigating connections, overlaps, and contradictions in the coded material. Often, this meant reconsulting original transcripts and field notes, continuously relating data extracts to their context. By investigating repeated patterns across the data set and relations between codes, candidate themes were generated and explored in relation to the full data set, until the final three themes were settled: (a) Setting the scene, (b) Dealing with uncertainty, and (c) Regaining control. All themes revolve around the process of interpreting the ambiguous CNV result and themes and subthemes are illustrated in Figure 1.

2.4 Ethics

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (J. No. 1-16-02-62-17). According to Danish law, approval by the National Committee on Health Research Ethics was not required as no biomedical intervention was performed (www.nvk.dk). However, the study was performed in accordance with the code of ethics for qualitative research as formulated by the American Anthropological Association (www.ethics.americananthro.org). The participants received oral and written study information about the aim and methods of the study, and consent was obtained prior to and after observations. Oral and written information was repeated at all interviews. The participants were informed that consent could be withdrawn at any time. All patient participants have been rendered anonymous through the use of pseudonyms and by omitting personally identifiable information. To secure the anonymity of geneticists, we have left out all personal information including gender and age because the study was conducted at a relatively small department. Furthermore, the prenatal genetics society in Denmark consists of relatively few members and even a little personal information would make the geneticists potentially identifiable.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Setting the scene

3.1.1 Session structure

All consultations roughly followed a three-stage structure where the couples were first invited to share their story. Most couples did this within a few minutes or less. They often started by expressing general worries and concerns about the whole situation, for example, ‘it's been a tough wait’. Some women got teary and some couples voiced frustration with the lack of information or a long and stressful diagnostic process. Without getting into specific details, the geneticists often acknowledged the worry and frustration of the situation.

Following the couples' story, the geneticist initiated the second stage of the consultation which focused on presenting the result. In this part, there was a clear asymmetry in the dialogue dominated by the geneticists' explanations. All consultations included a third stage of more equal dialogue where the geneticist and the couples sought to interpret further the result and to figure out—or at least approach—the potential implications for them and for the unborn child.

3.1.2 Presenting the CNV result

Geneticist 1: I usually think of the chromosomes as our personal library with 23 pairs of bookcases. In each pair of bookcases, you need two copies of each book—one from the mother and one from the father. (Couple 7, one child, paternally inherited VUS)

Geneticist 1: What we found was a small variation on chromosome 16. It is a lot less significant [than Down syndrome] and results in smaller challenges. But it can be—and often is—inherited from a parent. And that's why we examined you and now know that this variation originates from you [points to the woman]. (Couple 12, no children, maternally inherited SL)

Geneticist 2: We've found a variation on one chromosome, where a piece is missing. And we don't know what this piece is good for. With these small genetic variations, we often find that they are inherited from a parent. But this one is new. (Couple 14, one child, De novo VUS)

Geneticist 4: There's a limit to what the data can tell you. At some point, it stops being of value because we're all looking at probabilities here. So, you really have to get back to your guts and your sense of this whole situation: There are some uncertainties, can we live with that? (Couple 5, no children, paternally inherited SL)

After that, the couple put the list away and the geneticist initiated a talk about the prospective father's childhood and how that could provide information about a future scenario. In other consultations, the geneticists similarly tried to steer away from numerical risks after a while to instead address the couple's situation and concerns.

3.1.3 Healthy or not?

Mother: Coming here today, my main concern was: Will he be severely disabled? Because for me, that's not a life worth living. But developmental delay? That I can handle, no problem! (Couple 14, one child, de novo VUS)

Father: We talked about it and this is exactly the result we feared. We hoped for a sick or healthy result. This ‘gray’ result… that was exactly where we didn't want to end up. (Couple 13, no children, de novo VUS)

Mother: All we really want is a healthy child. But you cannot give us that, can you? (Couple 5, no children, paternally inherited SL)

However, regardless of the couples' initial response to the CNV result, all consultations included a process of negotiation and probing interpretations of the result and its consequences. The analysis identified two major themes in this process: Dealing with uncertainty and regaining control.

3.2 Dealing with uncertainty

In all consultations, the ambiguity of the result was acknowledged by speaking of it in terms of an ‘in-between’, ‘maybe–maybe not’ or ‘gray’ result. The analysis identified a number of specific interpretations and strategies that were used for dealing with the uncertainty of the result and the four most common ones are presented below.

3.2.1 Normalizing strategies

Mother: I had a horrible time in school, and my genes are normal! (Couple 4, no children, paternally inherited SL)

Geneticist 1: Are you disabled if it takes you a little longer to learn how to ride a bike? (Couple 8, three children, maternally inherited SL)

Geneticist 4 (smiling): In all pregnancies, there is a calculated risk of the child resembling one of its parents. (Couple 9, no children, paternally inherited VUS)

Mother: Well, I'm looking at you [partner], thinking that I wouldn't mind a little copy of you. (Couple 11, no children, paternally inherited SL)

Geneticist 2: I cannot give you guarantees, I wouldn't even give that guarantee to a couple with a normal test result either. You will NEVER know if bad things happen. (Couple 2, one child, maternally inherited SL)

Comments like this also served to normalize the ambiguous result by pointing to the inherent uncertainty in life in general—an uncertainty that couples with normal test results must also deal with.

3.2.2 Contextualizing strategies

Father: I guess it's just modern times. Maybe we can do more than what's for our own good? (Couple 13, no children, de novo VUS)

Father: Today, they would probably have diagnosed me with ADHD too! (Couple 15, no children, de novo SL)

Several couples suggested that society is too keen to put labels on normal children that deviate slightly from the norm, thereby indicating that this was something to resist—for example, by looking past the CNV result.

3.2.3 Leaning toward the positive

Geneticist 5: We see more of them [patients with 15q11 deletions] because they are more affected. People with duplications mostly feel normal. (Couple 6, three children, paternally inherited SL)

Geneticist 1: I suggest you turn around and look back at your family and your family history

Father (to mother): And we can't even figure out which of your parents it might be from. That's how normal your family is. (Couple 1, no children, maternally inherited SL)

Geneticist 3: There are a few reported cases like yours. But you have to understand that these are probably on the more severe end of the spectrum, chances are that many people with this variant will feel normal. It is just that we only investigate people that are sick, that have issues of some sort. So, it's a biased group. We don't know how many healthy people have this particular variation. (Couple 10, no children, maternally inherited SL and de novo VUS)

With explanations like this, the geneticists also exposed and shared the limitations of the currently available knowledge.

3.2.4 Naming what it's not

Geneticist 4: We have not found what I would call serious disease or genetic variation in your pregnancy. (Couple 2, one child, inherited SL)

Father: OK, so it's more like … like I am not paralyzed or have Downs syndrome or anything like that … so we're not speaking of those sorts of things?

Geneticist 1: No! Not at all! (Couple 7, one child, paternally inherited VUS)

This exchange took place 16 min into the consultation and in several other cases, it was well into the consultation before the couples asked the geneticist to confirm that severe physical or mental disability had actually been ruled out. The analysis revealed that communication about what was not found and could be ruled out was most often initiated by the couple and can be understood as a strategy to reduce ambiguity through comparison with what the couples perceived as a potentially worse situation, most often Down syndrome or severe autism.

3.3 Regaining control

In all consultations, it was possible to identify particular interpretations of the situation that allowed for action and made the CNV result useful in some way.

3.3.1 Continue or terminate?

Geneticist 2: It is a difficult situation to be in, but some couples come to terms with it quite easily: Now we have this knowledge and we are prepared for what might happen. We'll see what happens and take it as it comes. But there are others where this is completely new territory and who think … this sounds tough! This is not what we wanted or something we can handle. It really depends … There is no right or wrong, ok, and we'll support you in any decision that you make. (Couple 4, no children, paternally inherited SL)

Father: But I guess there's a point where … we can't just keep dragging out the decision … like, if we regret [the decision to continue]

Geneticist 1: Well, as you are more than 12 weeks along there are some limitations … Of course, if we—against all expectations—find something in the fetus in week 20, like in the heart, then you'll still have a choice […] But if a month from now, you change your mind and think the uncertainty is too much, then it will be uphill with an application. It will be difficult for you to …

Mother: So, we have to make the decision now?

Geneticist 1: Not necessarily now. But within a few weeks, yes. (Couple 13, no children, de novo VUS)

Eleven of the 12 pregnant couples chose to continue the pregnancy, one chose to terminate (Couple 16, two children, maternally inherited SL). This couple already had two young children of which one was a severely disabled and prior to testing they had decided that if anything showed up, they would terminate the pregnancy. Of the four couples who received a parentally inherited ambiguous CNV result following a terminated or lost pregnancy, all decided to forego pre-implantation genetic diagnostics and opt for natural conception in the next pregnancy.

3.3.2 The value of being prepared

Geneticist 1: With this information, you can intervene earlier and make sure that there is not a significant delay (in learning) before something is done. You may not need it at all, but you can keep it in the back of your mind. (Couple 1, no children, maternally inherited SL)

Mother: We both agree that with knowledge comes the opportunity to prevent things. And with this result, we already know that maybe we need to prepare for certain scenarios. Mmm … but it is also something that cast a bit of a shadow over our happiness. Knowing that there might be these issues … (Couple 5, no children, paternally inherited SL)

These mothers suggested that the result had introduced a sadness and concern during a time that they had expected to be happy and hopeful. In all these cases, the geneticist acknowledged that ‘knowledge comes with a price’ and encouraged the couple to put the worries to the back of their minds, if possible.

3.3.3 Identifying the next step

Mother: Thank you! We'd like that very much. It would be really nice for us to see him again.

Father: Yes, I think we really need that … (Couple 6, three children, paternally inherited SL)

This—and similar comments—indicated how the couples sought not only reassurance of fetal structural health but also sought to reconnect to the pregnancy and the child. An ultrasound offered a step in that direction and an opportunity to ‘do something’ that could potentially reestablish the happy pregnancy and the faith in a good outcome.

3.3.4 Embracing the child

Mother: With what we've heard here … In my heart, I feel that this is our child. (Couple 2, one child, maternally inherited SL)

Father: We need to … move on from all this gene stuff. And focus on him [the child]

Mother: Yes. We do. And he's gonna be perfect no matter what.

Father: I know. He is. (Couple 14, one child, de novo VUS)

Mother: We talked about … that if I felt safe about the pregnancy after this talk, then there was a question I really wanted to ask?

Father (smiling): I remember. Go ahead.

Mother (to geneticist): Can you tell me if it's a boy or a girl?

Geneticist 3: Of course. It's a boy.

Mother: Is it a boy? Oh wow, baby … it's Batman! He had a mutation too, you know! (laughter) (Couple 10, no children, maternally inherited SL and de novo VUS)

Inquiring about the gender was clearly a way for the couple to signal their investment in the pregnancy. Not all couples expressed this level of certainty about the situation and the pregnancy at the end of the consultation, but the majority spontaneously expressed relief and volunteered that the consultation had been of value to them. All couples conveyed that the information had been less severe than they had initially expected or feared.

4 DISCUSSION

Based on observation and audio-recording of genetic counseling sessions, this qualitative study explored the presentation of an ambiguous CNV result in a prenatal setting. The analysis focused on how geneticists and couples collaborated to deal with the uncertainties of the result and regain a sense of control of the situation. By proposing and negotiating different potential interpretations of the result—for example, normalizing uncertainty, contextualizing the result, and focusing on the value of being prepared—the geneticists and couples engaged in a process of making this new knowledge meaningful and manageable. Based on the analysis, we propose that these interpretations served to transform and reduce ambiguity through a process of reconfiguring the biomedical information into knowledge that resonated with the couples' lifeworlds. Below, we argue that in this process, both geneticist and couples drew on wider social and moral concerns about uncertainty and responsibility.

Our findings add a new perspective to previous studies of audio-recorded genetic counseling sessions. Studies of consultations regarding the decision to test have measured the affective tone and the extent of psychosocial exchange (Aalfs, Oort, de Haes, Leschot, & Smets, 2006) and levels of shared decision-making and decisional conflict (Birch et al., 2018). In a recent study of the return of genetic results in a postnatal setting, Walser et al. (2017) focused on the genetics healthcare providers' approach to the return of result and thus focused on the use of scientific jargon, probing questions and eliciting feedback. Our study adds to this body of knowledge through a focus on the collaborative practices of knowledge production in clinical interaction and on the shared interpretive repertoires used to make sense in an ambiguous situation. For example, both couples and geneticists referred to the fast-paced, modern society and the inevitable scientific progress as a way to justify or explain why they were put in a situation where they had to deal with an ambiguous CNV result. This interpretation puts the couple and the geneticist on ‘the same side’ and places responsibility for the difficult situation outside the consultation room.

Furthermore, our results show how the ambiguous CNV result is identified as ‘gray’ and thus as difficult compared with an unambiguous result of healthy or very ill. This resonates with much of the scientific literature and public discourse where uncertainty is most often portrayed as problematic and undesirable, as leading to confusion and anxiety, and as something that should be eradicated or avoided (Lupton, 2013; Newson, Leonard, Hall, & Gaff, 2016). However, in the consultations, another understanding was brought forth by both geneticists and couples; that uncertainty is inextricably part of human life, that we can never predict the future, and that children with ‘normal genes’ also struggle in school. This resonates with anthropological studies of risk and uncertainty in everyday life (Jenkins, Jessen, & Steffen, 2005), that highlight how uncertainty is a generic feature of everyday life. Complete certainty is never impossible, but we navigate in this by active attempts to create meaning, reasons, and degrees of certainty. Thus, the reference to life's inevitable uncertainty can be understood as reconfiguring and normalizing the CNV result to fit social and cultural understandings of everyday life, where the ambiguous CNV result can be dealt with alongside the other uncertainties we live with and navigate in. We thus agree with Newson et al. (Newson et al., 2016) that we need to reframe uncertainty from something that is intuitively negative to something that can be appraised and managed in more value-neutral ways. Our results are an example of how that is done in everyday clinical practice.

Another recurrent theme in the consultation was efforts to make the situation one of value due to its potential for action—primarily by pointing to the ‘value of being prepared to act’ as proposed by geneticists and couples in all consultations. Pointing to ways in which the couple can ‘do something’ with the ambiguous CNV result are ways of regaining control by being morally responsible persons who use knowledge as a step toward a desired future or outcome (Lupton, 1995; Petersen & Lupton, 1996). This interpretation draws on a strong Western value of individual responsibility of own health, and the cultural belief that through knowledge and actions, the future (health) can be controlled—for example, through knowledge of the child's genetic makeup and a focus on early intervention. The couples in the present study experienced a loss of control when receiving the ‘gray’ result; however, the analysis showed how they could reestablish control by framing the knowledge as valuable and powerful in predicting and preventing future events.

Our results also showed a shared understanding of knowledge as potentially dangerous because ‘being prepared’ could also put a shadow over the pregnancy as the couple could become too focused on future scenarios of delayed learning etc. Several other studies have pointed to the risk of medicalization in modern medicine in general (Conrad, 2007; Jutel, 2011) and prenatal diagnosis in particular (Lupton, 2013; Rapp, 1999). With the reporting of SL or VUS results, a new biomedically defined category of children is created: Children whose future development might be affected by a genetic variant. As Timmermans and Buchbinder (2010) observe in their study of newborn screening, once ambiguity is evoked, it does not easily disappear. Thus, these children may become ‘patients in waiting’ (Timmermans & Buchbinder, 2010)—children who hover in an in-between state between normal and pathological as children with potential learning disabilities or increased risk of psychiatric disorders. The issue here is that this may affect ‘the family's projection of the normality of their child’ (Timmermans & Buchbinder, 2010, p. 419). Our results show that this was also a concern for some couples. The relevance of this concern is confirmed by studies showing that parents of children with an abnormal genetic result engage in ‘watchful waiting’ and ‘active monitoring’ of the child's development (Bernhardt et al., 2013; Werner-Lin, Walser, Barg, & Bernhardt, 2017). Maybe the couple's concerns about the risk of future watchful waiting should be more actively addressed and potential coping strategies identified during the prenatal consultation.

In the study of the postnatal genetic counseling setting, Walser et al. (2017) found that the genetic counselors used conventional laboratory reports as a guide for presenting results to parents and often relied on explanations of genetics to relieve parents' concerns. Interestingly, the technical talk was relatively limited in the present study and the geneticists mostly kept explanations to a very general level, for example, ‘something missing on chromosome X’. They often tried to steer the conversation away from statistics and technical talk instead to address uncertainty and ambiguity. In clinical interactions about a VUS or SL result, a central premise is that there is a limit to the genetic information and that the future development of the specific child can only vaguely be predicted. Thus, at some point in the counseling, the traditional dichotomies in knowledge traditions—expert/lay, medical/experiential, science/belief—become blurry, and this may be what encourages the sharing of potential interpretations in the clinical interactions we have investigated. Based on these results, we suggest that shared uncertainty may be the ultimate democratization of the doctor–patient relationship and could be a platform for focusing not only on providing expert information but equally on the deliberative process in which the client and the genetics healthcare provider mutually engage in problem-solving. Our results suggest that shared social and cultural understandings provide a meaningful context and a shared language for this process.

4.1 Implications for practice

Our results may be useful to in other clinical settings. First of all, the consultation dialogue mainly revolved around how to understand and manage the ambiguity and uncertainty of the CNV result. Relatively little time was given to discuss what had been ruled out by the CMA, for example, several severe illnesses and syndromes. We suggest that genetics healthcare providers also address to this more certain information (about what is known about the baby's health) provided by the CMA result. Moreover, underscoring the normality of uncertainty seemed to be a good common ground for discussing the results and for relating the finding to similar situations in the couple's everyday life. Second, the analysis has made us aware of the sizeable and complex information and emotions, which couples (and genetics healthcare providers) deal with in these consultations. Thus, we now have a stronger focus on the need for follow-up contact and that this might need to be initiated by the genetics healthcare provider rather than the couples, who rarely call back, even though they are encouraged to do so. Finally, from the follow-up interviews (Lou et al., 2020), we learned that extra ultrasound examinations were a valuable strategy for controlling any lingering worry during pregnancy. Another strategy was to talk less about the CVN result and focus instead on the normal pregnancy. Ambiguous CNV results can be particularly difficult for the couples to explain and for the social network to understand, which can lead to misunderstandings, unthoughtful comments and continued questioning. Consequently, some couples experienced regret of disclosure. We usually encourage couples in genetic counseling to be open about their situation, but in cases of ambiguous results, the genetics healthcare provider can mention to the couple that they may want to be mindful of what information to share and with whom.

4.2 Study limitations

This study provides insight into the shape and content of clinical interaction, but does not offer insight into how geneticists and couples experienced the consultation—only what they openly expressed during the interaction. However, we have conducted subsequent interviews with all couples to explore their experiences and how the CNV result has influenced their lives in the months after the consultation (Lou et al., 2020). Also, we excluded all consultations where couples with a de novo result who chose TOP. These consultations could have added more information about how the difficult topic of TOP is addressed in genetic consultations, including issues of guilt and justification.

The study is relatively small and would benefit from a larger sample size including multiple Departments of Clinical Genetics and couples with more diverse backgrounds, for example, ethnic minorities. However, consultations were analyzed continuously throughout the recruitment period and continued until we estimated that sufficient information power was obtained (Malterud et al., 2015).

Finally, qualitative studies must always be understood within their specific context and are not generalizable in the quantitative sense of the concept; they are not intended to be. However, our results may be used as a lens through which genetic consultations in other contexts can be viewed, compared, and reflected upon.

4.3 Research recommendation

Several studies have investigated the importance of communicative skills and of individual values and preferences in genetic counseling. With this study, we identified how broader cultural and social understandings are brought into play when couples and genetics healthcare providers deal with ambiguous CNV results. It would be valuable to conduct similar studies in other cultural settings to compare differences and similarities between different contexts.

5 CONCLUSIONS

We have investigated clinical interaction as a formative practice in which knowledge about the fetus comes into being and identified a number of interpretive activities that transform the ambiguous CNV result into knowledge that is meaningful and manageable. The focus has been on the collective process where the biomedical knowledge is transferred to the lifeworld of the couple through a number of interpretive strategies. The results provide examples of how uncertainty and ambiguity can be addressed and negotiated in everyday clinical practice. Such insights may be of value in a genetic setting as well as other ambiguous situations of clinical decision-making.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

SL, OBP, KL and IV substantially contributed to the conception or design of the study. SL and IV contributed to the acquisition of data, and all authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. SL drafted the manuscript, and OBP, KL, and IV revised it critically, gave final approval of the submitted manuscript, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the participating geneticists and couples who let us observe and record consultations. Thank you for your trust; we hope our findings resonate with you.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Conflict of interest

The authors SL, OBP, KL, and IV declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human studies and informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with Danish legislation and the Helsinki Declaration of 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all participants (geneticists and couples) included in the study.

Animal studies

No nonhuman animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.