Sickle cell carriers' unmet information needs: Beyond knowing trait status

Funding information

The project described was supported by the National Center for Research Resources, Grant UL1 RR024975-01, and is now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant 2 UL1 TR000445-06. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Abstract

Benefits of identifying sickle cell disease (SCD) carriers include detection of at-risk couples who may be informed on reproductive choices. Studies consistently report insufficient knowledge about the genetic inheritance pattern of SCD among people with sickle cell trait (SCT). This study explored perspectives of adults with SCT on the information needed to make an informed reproductive decision and the recommendations for communicating SCT information. Five focus groups (N = 25) were conducted with African Americans with SCT ages 18–65 years old. Participants were asked about their knowledge of SCT, methods for finding information on SCT, impact of SCT on daily living, and interactions with healthcare providers. An inductive-deductive qualitative analysis was used to analyze the data for emerging themes. Four themes emerged, highlighting the unmet information needs of African American sickle cell carriers: (a) SCT and SCD Education; (b) information sources; (c) improved communication about SCT and SCD; and (d) increased screening strategies. Future studies are needed to determine effective strategies for communicating SCT information and to identify opportunities for education within community and medical settings. Identifying strategies to facilitate access to SCT resources and education could serve as a model for meeting unmet information needs for carriers of other genetic conditions.

1 INTRODUCTION

The concept of shared decision-making between patients and providers is increasingly recognized as a critical element to patient-centered care. To achieve balance in participation between the patient and provider, patients must be equipped with the proper information to assist in making the best healthcare decision (Tang, Newcomb, Gorden, & Kreider, 1997). Patients may require additional health-related information to fully engage in healthcare decisions (Bradford, Roedl, Christopher, & Farrell, 2012). Recent studies suggest patients desire more information than they receive (Longtin et al., 2010), a need often overlooked by providers (Washington, Meadows, Elliott, & Koopman, 2011). For individuals at high risk of their children inheriting a serious genetic condition, such as couples with sickle cell trait (SCT), comprehensive genetic information is needed to facilitate informed reproductive health decisions and behaviors.

Individuals with SCT have a mutation that causes them to make hemoglobin S instead of beta-globin (HBB) from one of their two copies of the HBB gene (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI], 2018). Approximately one in 12 African Americans has SCT and are known as sickle cell carriers (CDC, 2015; NHLBI, 2018). Despite SCT being identified during newborn screening, there is no universal method of parental notification of SCT status (Gustafson, Gettig, Watt-Morse, & Krishnamurti, 2007; Pass et al., 2000). In addition, many states do not offer genetic counseling to parents of children with sickle cell disease (SCD) and SCT (Centers for Disease Control [CDC], 2017). For states that offer genetic counseling, uptake is generally low (Acharya, Lang, & Ross, 2009; Goldsmith et al., 2012; Long, Thomas, Grubs, Gettig, & Krishnamurti, 2011).

There are two areas of information needed for carriers, reproductive implications and health risks. While most individuals with SCT will not have any health complications, occasionally people with SCT can have blood in their urine (CDC, 2017; NHLBI, 2018). In rare cases, and under extreme conditions (e.g., high altitude, severe dehydration, or very high intensity physical activity) red cells can become deformed or sickled. This could potentially result in rhabdomyolysis, renal complications, and venous thromboembolism (American Society of Hematology [ASH], 2019; Pecker & Naik, 2018). Therefore, among African Americans, concerted efforts have been implemented to: (a) increase awareness of SCT status along with its' potential risks for associated sequelae (Harbi, Khandekar, Kozak, & Schatz, 2016; Bleyer et al., 2010; Khan, Kleess, Yeh, Berko, & Kuehl, 2014; CDC, 2009; Thoreson, O'Connor, Ricks, Chung, & Sumner, 2015); and (b) disclose reproductive risks for SCD among those who have been identified as carriers (Boyd, Watkins, Price, Fleming, & DeBaun, 2005; Housten, Abel, Lindsey, & King, 2016; Long et al., 2011; Treadwell, McClough, & Vichinsky, 2006). However, studies indicate that messages communicated to carriers on the significance of SCT are inconsistent (Miller et al., 2010).

Communicating information to patients and family members about how SCT is inherited can be a challenge for providers, especially for those who are not trained in hematology or genetic counseling. General practitioners, whose clientele includes patients with SCT, are often tasked with deciding how much information to disclose, streamlining the communication process, and balancing information sharing in the context of uncertainty of how it will impact patients (Lautenbach, Christensen, Sparks, & Green, 2013). Despite providers offering information, resources, and education to facilitate informed decision-making, studies consistently report that sickle cell carriers have insufficient or erroneous knowledge about the risk of complications associated with SCT, the genetic inheritance pattern of SCD, and are misinformed about their own or their partner's SCT status (Acharya et al., 2009; Creary et al., 2016).

Misinformation on SCT has great implications for patients who subsequently have children without awareness or understanding of the reproductive risks or implications of the disease for their child. Couples are, therefore, educationally challenged in their decisions to: (a) not have a child; (b) potentially have a child with SCD or SCT; (c) seek other non-childbearing options such as adoption; or (d) use assisted reproductive technologies options to have a child without SCD. Such options could include: sperm donor; egg donor; pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (Gallo et al., 2010; DeRycke et al., 2001). Thus, it is imperative to close gaps in the information needs for sickle cell carriers to facilitate informed reproductive health decisions.

The purpose of this study was to explore perspectives of adults with SCT on the information needed to make an informed reproductive decision and the recommendations for communicating SCT information. From this study, key patient stakeholders (i.e., providers, genetic counselors, and SCD community-based organizations) will become aware of the information they need to offer these patients to promote shared decision-making. Also, findings may offer a better understanding of strategies (Nutbeam, McGill, & Premkumar, 2017) needed to better communicate complex genetic health information to sickle cell carriers.

2 METHODS

2.1 Design

We conducted a descriptive, qualitative study that involved focus groups composed of a purposive sample of 25 individuals with SCT in Tennessee. All protocols and procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Meharry Medical College (Protocol #16-06-559). Prior to data collection, a community engagement (CE) studio was conducted to gain input on focus group questions and recruitment from sickle cell community members (i.e., individuals with SCT, individuals with SCD, and family members). A CE studio is a structured way to promote meaningful engagement of the community in research by encouraging feedback using a facilitator (Joosten et al., 2015). Sickle cell community members offered input on the study design, including the inclusion criteria, focus group questions, and recruitment strategies. Feedback on focus group questions included question comprehension and question content to ensure the researcher would obtain the necessary information to answer the research question. Feedback on recruitment materials included using pictures to fit the target demographic. Focus group questions and recruitment materials were updated as a result of this feedback. The questions were incorporated into a focus group moderator's guide that included an introduction, ground rules, main questions, and probes.

2.2 Study participants and procedures

We conducted a series of focus groups (N = 5) among 25 African Americans with SCT ages 18–65. (Note: The age criterion was modified from an original 18–35 after community input). Participants were recruited through a community-based organization, the Sickle Cell Foundation of Tennessee, and flyers posted at community locales such as health centers and churches. Sickle cell trait status was confirmed via self-report. An eligibility screening tool was developed and utilized to ensure participants met the study requirements. Questions included: (a) Do you know whether you have SCT?; and (b) How were you informed of your positive trait status? After obtaining informed consent from each participant, the “ground rules” were explained (e.g., confidentiality, allowing each member to respond to every question and the permissibility of cross-discussion).

Participants were asked to complete a short, self-administered questionnaire prior to conducting the focus group. The questionnaire included basic demographic questions along with SCT-related information on the following: (a) child's sickle cell status (SCT or SCD); (b) future reproductive decisions; and (c) method of learning SCT status. Then, focus groups were conducted by a member of the research team who had training in qualitative research methods. Using the detailed moderator guide, participants were asked about their knowledge of SCT, methods for finding information about SCT, impact of SCT on daily living activities, and interactions with healthcare providers. (See facilitator guide at https://healthbehavior.psy.vanderbilt.edu/mayo-gamble/MayoGambleFacilitatorGuide.pdf). Each focus group session lasted approximately 2 hours and each participant received $25 after the session. Focus group discussions were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed for data analysis.

2.3 Analysis

Qualitative data coding and analysis were managed by the Vanderbilt University Qualitative Research Core, led by a PhD-level psychologist. Data coding and analysis were conducted by following the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research guidelines (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007), an evidence-based qualitative methodology. Preliminary analysis of focus groups began after the first two groups were completed, and consistent with established qualitative research methods. Additional focus groups were then conducted until thematic saturation was achieved. A hierarchical coding system was developed based on study questions and preliminary review of the transcripts. Experienced qualitative coders first established reliability in using the coding system, then independently coded each transcript. Coding of each transcript was compared, and any discrepancies were resolved to create a single coded transcript. Each statement was treated as a separate quote and could be assigned up to five different codes. Transcripts were combined and sorted by code. Analysis consisted of interpreting the coded quotes and identifying higher-order themes using an iterative, inductive-deductive approach.

Data analysis was performed on the sorted, coded quotes. Then, individual quotes within each coding category were reviewed. An analyst kept notes and began to identify higher-order themes and connections between categories. Analysis alternated between induction and deduction. Inductively, we relied on the Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1989,2001), a Biopsychosocial framework (Engel, 1977,1992), and clinical knowledge and experience working with Social Cognitive Theory. Deductively, specific quotes were used to fill in the details. Finally, selective coding was conducted to identify key areas of information needs among adults with the Social Cognitive Theory. The final analytic product was a conceptual framework that organized the unmet information needs of individuals with Social Cognitive Theory. All authors reviewed the final themes and reached consensus that they accurately reflected the data. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the demographic and SCT-related characteristics of participants.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Characteristics of participants

Table 1 presents the characteristics of focus group participants. Of the 25 focus group participants, 22 were female and three were male. Most participants were aged 36–45, had some college education or an undergraduate degree, and were employed full-time. Table 2 illustrates SCT-related characteristics. Most participants had at least one child with SCT or SCD, did not plan to have additional children, and were informed of their carrier status by a parent.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–25 | 3 (12.0) |

| 26–35 | 7 (28.0) |

| 36–45 | 8 (32.0) |

| 45–55 | 5 (20.0) |

| 55–65 | 2 (8.0) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 22 (88.0) |

| Male | 3 (12.0) |

| Education | |

| Some high school | 1 (4.0) |

| High school diploma/ GED | 3 (12.0) |

| Some college | 6 (24.0) |

| Undergraduate degree | 11 (44.0) |

| Postgraduate work/degree | 4 (16.0) |

| Employment Status (employed) | |

| Unemployed | 6 (24.0) |

| Employed part-time | 5 (20.0) |

| Employed full-time | 13 (52.0) |

| Retired | 1 (4.0) |

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| What is your child's sickle cell status? | |

| At least one child w/sickle cell disease | 6 (24.0) |

| At least one child w/sickle cell disease trait | 12 (48.0) |

| No children with sickle cell disease or trait | 7 (28.0) |

| Future parity | |

| No | 19 (76.0) |

| Yes | 6 (24.0) |

| How did you become aware of your sickle cell trait status? | |

| After my child's positive newborn screening | 5 (20.0) |

| Parent told me | 15 (60.0) |

| Adult screening | 5 (20.0) |

3.2 Qualitative findings

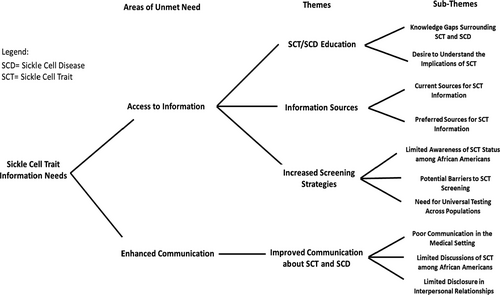

This goal of this study was to elicit perspectives of information needed and recommendations for communicating this information expressed by individuals with SCT. Four major themes were identified: (a) SCT and SCD education; (b) information sources; (c) improved communication about SCT and SCD; and (d) increased screening strategies. Table 3 outlines the major themes, subthemes, specific categories, and representative quotes. Themes were grouped into two areas of unmet information needs: access to information and enhanced communication. Access to information included three major themes: SCT and SCD Education, Information Source, and Increased Screening Strategies. Enhanced communication had one main theme which was Improved Communication about SCT and SCD. Figure 1 illustrates the four themes representing unmet information needs as expressed adult sickle cell carriers. Each of the main themes is discussed in detail below.

| Themes | Subthemes | Coded categories | Examples of representative quotesa |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCT/SCD education | Knowledge gaps surrounding SCT and SCD |

|

It's an inherited disease [F5]. |

|

I already have one child with sickle cell disease so the next one shouldn't [FG2]. | ||

|

Primary care doesn't provide much info [FG1]. | ||

| Desire for information on the implications of SCT and SCD |

|

When you look online there's no information on the trait [FG2]. | |

|

You have the trait and may have children in the future with sickle cell disease [FG4]. | ||

| Information sources | Current sources for SCT Information |

|

Now you can look anything up on the internet [FG3]. |

| Preferred sources for SCT and SCD information |

|

They need to have a support group for sickle cell trait and the disease [FG1]. | |

|

Schools should provide education and raise awareness [FG1]. | ||

| Improved communication about SCT and SCD | Poor communication within the medical setting |

|

They said you've got a trait, and it's nothing to be worried about [FG5]. |

|

You just check it off on a piece of paper. Sometimes I don't even check it off [FG3]. | ||

| Limited discussions of SCT among African Americans |

|

They sent me a letter saying I need to come back [FG5]. | |

|

They didn't give me any information. They just said I had trait. They didn't give me nothing. [FG2] | ||

|

We don't hear about sickle cell [FG4]. | ||

| Limited disclosure in interpersonal relationships |

|

I think my biggest problem is not knowing what side of the family it actually came from [FG2]. | |

| Increased screening strategies | Limited awareness of SCT status among African Americans |

|

My friends…do not know to this day if they have it or not [FG3]. |

|

I was 7 months pregnant when I found out I had the trait [FG1]. | ||

|

Now you're no longer just doing it with the African American population [FG5]. | ||

| There is a need for universal testing across populations |

|

My daughter's husband, he didn't know he had the trait [FG3]. | |

|

I wonder if it's very expensive [FG2]. I didn't know anything about it [FG4]. |

Note

- SCD: sickle cell disease, SCT: sickle cell trait.

- a Each quote represents a single participant's response.

3.2.1 Theme 1: SCT and SCD education

Sickle Cell Trait and SCD Education describes the awareness and knowledge carriers have on SCT and SCD. It also characterizes their desire to learn more about their status. This theme had two subthemes: knowledge gaps surrounding SCT and SCD, desire for information on the implications of SCT and SCD. Responses from participants reflected gaps in knowledge on SCT, “I really didn't have no understanding about it.” [FG4]; “I didn't know the chances that it would be passing it onto a child.” [FG1]; “All I know is that it's dealing with your blood cells” [FG2]. Other responses reflected a desire to acquire information on SCT, “The education has to be on the consumer side” [FG5]; “We would love to see more information.” [FG4] Additionally, a few participants noted that the gaps in knowledge are not only among consumers but also with providers, stating, “A lot of the doctors are misinformed.” [FG4].

3.2.2 Theme 2: Information sources

Information Sourcesdescribe the current resources available and preferred methods for receiving information on SCT and SCD. This theme included two subthemes: Current Sources for SCT Information and Preferred Resources for SCT and SCD Information. Some participants discussed the methods they personally use to find SCT information and methods in which they have received information from external sources: “If I have questions about it, I just look online” [FG3]; I use Google a lot” [FG3]; “I was diagnosed, so they gave me a brochure”[FG5]; “They [provider] sent it in the mail” [FG4]; “It was a letter. It was one paragraph saying that your results are abnormal” [FG1]. Others used this as an opportunity to recommend strategies for disseminating SCT information: “Information should be sent from sickle cell foundation or local organizations” [FG2]; “If you get it from maybe a doctor or someone who is actually dealing with sickle cell, I think that's the best way to know” [FG5]; “it would [behoove] the medical industry to give more information about trait.” [FG3].

3.2.3 Theme 3: Improved communication about SCT and SCD

Improved Communication about SCT and SCDreflects the limited and poor communication experiences of sickle cell carriers when discussing SCT and SCD in interpersonal, community, and medical settings. This theme included three subthemes: poor communication within the medical setting; limited discussions of SCT among African Americans; and limited disclosure in interpersonal relationships. Participants expressed several concerns regarding their inability to effectively communicate with healthcare providers about SCT: “They [doctors] don't care to listen.” [FG4]; “[Primary] care doctor never asks me about my trait.” [FG1]; “They said you've got a trait, and it's nothing to be worried about.” [FG5] Conversely, when opportunities arise for participants to speak with their provider about SCT, participants described retreating or not discussing this health issue: “When doctors ask me the history I never bring that up.” [FG2]; “I put SCT on the back burner.” [FG3].

Communication about SCT was limited outside of the medical setting. Participants spoke on both the dearth of discussion on the genetic status within families and within the African American community: “Black community just don't want to open their eyes to the existence” [FG2]; “My daughter's husband, he didn't know he had the trait.” [FG1] Some participants further described challenges of communicating SCT diagnoses in interpersonal relationships: “My daughter's father just said, ‘Well you know, I have sickle cell trait and if we ever have a kid, I would be like pray for the first six months.” [FG1]; “Why didn't you tell me your whole family was sick and now my baby's sick for the rest of his life.” [FG3]; “She was like why didn't you tell me that your family was sick?” [FG2] Finally, participants provided insight on their experiences of learning their SCT outside of the medical setting: “My mom told me is you have the trait and that was it. She didn't explain what it was or anything.” [FG1]; “My mom just said you had the trait when I was little but nothing else.” [FG5]; “All I know is my mom said all of us have the trait.” [FG1] These responses reflect an absence of explanations for SCT that accompany initial awareness of SCT status.

3.2.4 Theme 4: Increased screening strategies

Increased screening strategies emphasized the perceived importance of screening to identify sickle cell carriers. This theme had three subthemes: delayed awareness of SCT status, potential barriers for SCT screening, and there is a need for universal testing across populations. Despite knowing their personal SCT status, participants expressed their perspectives on the importance of universal screening and barriers that might prevent individuals from seeking to learn their SCT status. Participants stated: “I'm hoping that you're not just running the trait on African Americans” [FG5]; and “My friends they say they never been tested.” [FG1].

Examples of barriers to screening include: “I wonder if it's very expensive” [FG2]; and “They sent me a letter saying I need to come back. Now, that's what scared me.” [FG5]; “When I went in they talked to me about the trait, but by then I'd already had all my children.” [FG1]; “We found out my child had sickle cell during newborn screening.” [FG3].

In addition to identifying qualitative themes, discussions of SCT prompted questions from participants. Questions arose during responses to one specific focus group question, “What do you know about SCT?” Examples of participant questions were organized into two categories: causes of SCT and symptoms resulting from SCT (Table 4). These questions are illustrative of the specific information participants were interested in but have either never received answers to these questions or have not been received an educational opportunity to get responses to their questions.

| Causes of sickle cell trait |

| Did both of my parents have sickle cell trait in order for me to get it? |

| Can you get sickle cell trait if you are not Black? |

| Does malaria cause sickle cell trait? |

| Does sickle cell trait cause sickle cell disease? |

| What's the point of getting screened for sickle cell trait? |

| Symptoms resulting from sickle cell trait |

| Is sickle cell trait a disease? |

| What kinds of symptoms do people with sickle cell trait have? |

| Does sickle cell trait cause kidney damage? |

4 DISCUSSION

Sickle cell carriers may face challenges making health and reproductive decisions. Among these challenges is adequate and accurate understanding of genetic information. Several studies have been conducted on strategies to increase awareness of sickle cell carrier status and knowledge of SCD inheritance. Yet, previous studies are limited in capturing the experiences and actions taken by patients following SCT identification. Community-based efforts are becoming increasingly effective in offering preconception screening. However, it is important to acknowledge that screening without proper or adequate education following trait identification does not prepare carriers to make informed reproductive decisions, a major issue carrier screening seeks to rectify. We addressed this gap by providing insight on major areas of unmet information needs for sickle cell carriers.

All study participants were aware of their carrier status, yet many had not received information consistent with the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) recommendations to ensure adequate understanding of the SCT. The recommendation states individuals should receive: (a) a full explanation of the SCT confirmation results; (b) SCT education; (c) counseling; and (d) offering testing for the partner if a carrier couple is contemplating having children (HRSA, 2010). In this study, participants who learned their SCT status from their parents, received an explanation that was limited to their SCT status. For participants who learned of their status as adults, information was limited to HRSA categories 1 and 2, and in many cases, occurred after having a child diagnosed with SCD or SCT through newborn screening.

4.1 Practice recommendations

Discussions about SCT within personal and healthcare settings rarely occur after identification of trait status. Participants indicated several methods of learning their SCT status (e.g., parents, healthcare provider, lab results in the mail). Unfortunately, these methods were either unaccompanied by additional information on SCT or left participants too frightened to follow-up with a provider or genetic counselor to learn about SCT implications. Thus, a need exists to move beyond screening for the purpose of identifying sickle cell carriers. We must determine more effective strategies to communicate SCT status and ensure those identified as sickle cell carriers fully understand the implications of their carrier status.

For many carriers, including those in the present study, there was confusion on the inheritance pattern of SCD and the number of children they could potentially have with SCD. Specifically, participants understood SCD genetic risk as the potential for one child of every four to have SCD (Ex. “I already have one child with SCD so the next one shouldn't.”). Subsequently, this demonstrates a need for more patient-friendly education that offers lay language on: (a) future reproductive implications; and (b) risk complications in the individual with SCT or for their child with SCD. These findings also suggest a need for more effective strategies to improve patient-provider communication surrounding SCT to improve the ability to engage in an informed decision-making process. Particularly, there is a need to improve information on genetic risk. For example, it was apparent that when information on the genetic risk for SCD was received, carriers did not accurately understand these risks. Therefore, implementing strategies such as the “teach-back” method may be helpful to confirm that this information has been accurately received (Nutbeam et al., 2017; Porter et al., 2014). This method is shown to be effective in genetic education (Porter et al., 2014; Tluczek et al., 2011). Teach-back techniques involve asking participants to use their own words to illustrate their understanding of material discussed (Kripilani, Bengtzen, Henderson, & Jacobsen, 2008). Coupled with a comprehensive understanding of sickle cell carrier information needs, this strategy could be employed to promote informed and shared decision-making.

Communicating genetic risk information is not a traditional expectation for primary care providers. However, as access to genetic information becomes increasingly available, clinicians of all specialties will need to be well versed in the nuances of this communication. Participants in this study had attempted to discuss SCT with their healthcare providers. They indicated that providers place an emphasis on the benign nature of SCT, as indicated by statements such as “They said you've got a trait, and it's nothing to be worried about.” These discussions left participants feeling that their concerns were not validated and that their questions were not sufficiently answered. However, findings from this study also indicate that participants did not expect their healthcare providers to be equipped to answer all questions on SCT. Yet, there was an expectation that providers would listen to their concerns and direct them to reputable resources if needed. Participants suggested genetic counselors and SCD local or national organizations as reputable resources for SCT and SCD information. Since individuals with SCT identified genetic counselors as an acceptable source for SCT information, primary care providers should continue to refer carriers for genetic counseling. These suggestions are also applicable for other inherited recessive genes in which communicating genetic risk information is problematic (e.g., cystic fibrosis and Tay-Sachs disease).

While participants expressed challenges communicating about SCT within medical settings, the onus is not only on providers. Participants acknowledged that when opportunities for discussions of SCT are initiated by a healthcare provider, they often refrain from having these discussions or neglect to disclose their SCT status. These findings suggest that strategies should be in place to encourage or facilitate communication about SCT between patients and their providers. Similarly, participants indicated that as African Americans, discussions about their health status with family members or friends do not occur. One participant acknowledged that when they informed their partner of their SCT status, there was little to no discussion on the reproductive implications. This suggests that overall, sickle cell carriers are in need of education on how to have conversations about the SCT status. Facilitation of communication may also be an area for genetic counselors to intervene. During genetic counseling sessions, individuals and/or couples with SCT could benefit from education on strategies on communicating reproductive implications to their partner.

4.2 Research implications

Much of the current research on sickle cell carriers focuses on increasing knowledge of SCT, increasing knowledge of SCD, and providing reproductive counseling (Creary et al., 2016; Housten et al., 2016; Ulph, Cullinan, Qureshi, & Kai, 2014,2015). While these are areas of great importance for SCT, studies are beginning to highlight the issue of intergenerational communication. The first point of communication on SCT and SCD typically occurs between the health professional and the parent. Ultimately, this information has the greatest significance for the child. Many participants in this study had received information on SCT from their parents. Yet, by the time their parents informed them of their trait status, the parents were unable to articulate key components of information conveyed to them by providers during newborn screening. In addition, participants who were either beyond reproductive age or had no plans to have additional children acknowledged the need to understand the reproductive and health implications of SCT to better communicate with their children, family members, and healthcare providers. Thus, research is needed to assist families in negotiating further communication on SCT and SCD.

Studies on the association between health literacy and SCT genetic knowledge are limited (Creary et al., 2016). Further research is warranted to provide sickle cell carriers with written informational support that meets their health literacy needs. Participants in this study indicated that the written documents they received from providers were inadequate. Studies have shown that primary care providers have SCT and SCD brochures and other informational resources readily available but do not remember to offer them to patients and parents of patients SCT (Bradford et al., 2012; Coulson, Buchanan, & Aubeeluck, 2007). Additionally, studies have shown that patients prefer high-quality information and may seek highly technical information; yet the standard brochures providers distribute very little technical information (Coulson et al., 2007). Identifying patient preferences for information material type, content, and literacy levels not only could aid providers in filling gaps in SCT and SCD knowledge, but also could facilitate communication on SCT within families.

4.3 Study limitations

This qualitative study employed focus groups. The sample of focus group participants could be skewed toward participants who find it easier to talk about their carrier status. This was also a highly educated population that may not be necessarily representative of the general population. However, the similarities between some of our core themes and those found in other studies permit confidence in the validity of our data and analysis of the data. Next, while results are not necessarily generalizable outside of the sample population, we believe our results are transferable to other genetic contexts. Finally, the sample included older participants whose views on the reproductive implications of SCT differ from those within reproductive age. Despite the limitations of the study, we believe the strengths of this study outweigh the limitations and provide a foundation for future research. This research addressed important gaps in the literature on miscommunication about SCT and information needs to support informed decision-making.

5 CONCLUSION

This study contributes to the literature on patient unmet information needs by highlighting the needs of sickle cell carriers. Participants within this study identified two primary areas of need, access to information and enhanced communication. It was evident through participant responses that even among sickle cell carriers, there are gaps in knowledge on issues pertinent to this population including definition of SCT, reproductive implications, and health risks. Further, efforts to close these information gaps are limited by the inability to effectively communicate within medical and personal settings about SCT status. Future studies are needed to determine effective strategies for communicating complex SCT information and to identify opportunities for education within community and medical settings. Identifying strategies to facilitate access to resources and increased education on SCT for this carrier population could serve as a model for meeting unmet information needs of carriers of other genetic conditions.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Tilicia L. Mayo-Gamble substantially contributed to the conception and design; the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. David Schlundt substantially contributed to the conception and design; analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Jennifer Cunningham-Erves substantially contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Velma McBride Murry substantially contributed to the conception and design; analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Kemberlee Bonnet substantially contributed to the analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Delores Quasie-Woode substantially contributed to the analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Charles P. Mouton substantially contributed to the conception and design; analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank Tiffany L Israel, MSSW, Community Navigator, at the Vanderbilt Institute for Medicine and Public Health for facilitating the CE Studio and the Sickle Cell Foundation of Tennessee for assisting with recruitment. This work was conducted as part of Dr. Mayo-Gamble's post-doctoral training.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

All authors of this manuscript declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human studies and informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all participants for being included in the study.

Animal studies

No animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.