The mitochondrial metabolic reprogramming agent trimetazidine as an ‘exercise mimetic’ in cachectic C26-bearing mice

Abstract

Background

Cancer cachexia is characterized by muscle depletion and exercise intolerance caused by an imbalance between protein synthesis and degradation and by impaired myogenesis. Myofibre metabolic efficiency is crucial so as to assure optimal muscle function. Some drugs are able to reprogram cell metabolism and, in some cases, to enhance metabolic efficiency. Based on these premises, we chose to investigate the ability of the metabolic modulator trimetazidine (TMZ) to counteract skeletal muscle dysfunctions and wasting occurring in cancer cachexia.

Methods

For this purpose, we used mice bearing the C26 colon carcinoma as a model of cancer cachexia. Mice received 5 mg/kg TMZ (i.p.) once a day for 12 consecutive days. A forelimb grip strength test was performed and tibialis anterior, and gastrocnemius muscles were excised for analysis. Ex vivo measurement of skeletal muscle contractile properties was also performed.

Results

Our data showed that TMZ induces some effects typically achieved through exercise, among which is grip strength increase, an enhanced fast-to slow myofibre phenotype shift, reduced glycaemia, PGC1α up-regulation, oxidative metabolism, and mitochondrial biogenesis. TMZ also partially restores the myofibre cross-sectional area in C26-bearing mice, while modulation of autophagy and apoptosis were excluded as mediators of TMZ effects.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our data show that TMZ acts like an ‘exercise mimetic’ and is able to enhance some mechanisms of adaptation to stress in cancer cachexia. This makes the modulation of the metabolism, and in particular TMZ, a suitable candidate for a therapeutic rehabilitative protocol design, particularly considering that TMZ has already been approved for clinical use.

Introduction

Cachexia is defined as the loss of body weight occurring in the presence of chronic illnesses such as cancer or chronic heart failure. Cachexia severely interferes with patient responsiveness to therapy and contributes to poor prognosis, reducing both quality of life and survival.1-9 The loss of skeletal muscle mass in cachectic states is due to excessive catabolism of myofibrillar proteins, which might be associated to reduced protein synthesis. Both processes are mediated by PI3K/AKT-dependent pathways that reduce the expression of molecules regulating proteasomal degradation such as atrogin-1/MAFbx and Muscle Ring Finger protein 1.10-17 Moreover, the activation of PI3K/AKT-dependent pathways increases protein synthesis by targeting, among other molecules, glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β) and S6 kinase 1 phosphorylation.18-20 Muscle mass depletion in cachexia has also been associated to altered autophagy and impaired myogenesis.21-26

Metabolic efficiency of the myofibre is critical for maintaining muscle physiology and function and for avoiding loss of skeletal muscle mass.27-29 From a metabolic point of view, skeletal muscles are composed of myofibres with different metabolic profiles ranging from those with a prevalent glycolitic metabolism to those predominately oxidative. Myofibres also display different contractile properties that allow a classification in slow-twitch or fast-twitch fibres30-32 and that are strongly related to the isoform of myosin heavy-chain (MyHC) that they express. In particular, myosin ATPase type I identifies slow-twitch type I myofibres (predominately oxidative), while myosin ATPase type II identifies type II fast-twitch myofibres (mainly glycolitic). Type I fibres are characterized by both high mitochondrial content and high capillary density.33 Also, other myofibrillar (e.g. Troponin T, I, and C) and calcium-sequestering (e.g. the sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium transport ATPase) proteins are expressed as slow or fast isoforms, predominately occurring in type I or II fibres, respectively. In rodents, based on the isoform of fast MyHC expressed, type II fibres are further classified into three subclasses; type IIa, type IIx/d, and type IIb fibres. Type IIx/d fibres are glycolitic, whereas, compared with type I and to type IIx/d fibres, type IIa fibres have intermediate features and a mixed (oxidative/glycolytic) metabolism. Finally, type IIb fibres are more fast-twitch and glycolytic than IIx/d fibres.30, 31

Mammalian skeletal muscle is a highly plastic tissue in which myofibre physiological properties and metabolism vary in order to optimize the response to the changing environment. Some drugs are able to modulate cell metabolism and to enhance cell metabolic efficiency.34-37 In particular, the metabolic modulator trimetazidine (TMZ) reduces fatty acid oxidation by inhibiting 3-ketoacyl Co-A thiolase and shifts ATP production from fatty acid oxidation towards glucose oxidation. ATP synthesis through fatty acid β-oxidation requires more oxygen compared with glucose oxidation; therefore, the choice of glucose as a substrate induces a more efficient utilization of the oxygen available, which in turn increases metabolic efficiency38,39-42 We have already demonstrated that this drug has a hypertrophic effect on cultured myotubes and that it improves exercise capability in patients suffering from chronic stable angina.43, 44 Based on these premises, we investigated whether TMZ can counteract skeletal muscle dysfunctions occurring in cancer cachexia by using mice bearing the C26 colon carcinoma. In this regard, the C26 tumour is the most widely used experimental model in the field of cancer cachexia, which has been shown to reasonably recapitulate the most relevant clinical features of this syndrome.45 Our experiments revealed that TMZ administration induces some of the benefits achieved through exercise, possibly enhancing the mechanisms of adaptation to stress.

Methods

Animals and experimental design

Balb-c male mice (5 weeks old) were used. They were obtained from Charles River and were maintained on a regular dark–light cycle (light from 08:00 to 20:00), with free access to food (Piccioni) and water during the whole experimental period, including the night before sacrifice. Experimental animals were cared for in compliance with the Italian Ministry of Health Guidelines (no 86609 EEC, permit number 106/2007-B) and the Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH 1996). The animals were randomized according to their body weight on the day before the treatments and divided into four groups, namely, controls and tumour bearers, treated or not with TMZ (Sigma-Aldrich). Because we evidenced the instability of TMZ powder, we always used fresh TMZ, not older than 1 month after package opening. Sample size has been defined on the basis of previous studies. In particular, 6–7 mice/experimental group (depending if healthy or tumour-bearing) have been estimated sufficient to detect a difference of 10 in the means of each parameter with a SD of 8 and with 90% power, a significance level of 95% at Student's t-test, and a dropout rate of 10%. In more detail, the first group (Ctrl; n = 6) served as controls and included healthy mice inoculated with vehicle (saline); the second group (TMZ; n = 6) included healthy mice receiving intraperitoneal injection of 5 mg/kg TMZ once a day for 12 consecutive days; the third group (C26; n = 7) included tumour-bearing mice inoculated subcutaneously dorsally with 5 * 105 C26 carcinoma cells; the fourth group (C26-TMZ; n = 7) was inoculated with C26 cells and the same day started receiving TMZ intraperitoneal injection of 5 mg/kg TMZ once a day for 12 consecutive days. Based on the most recent indications suggesting that, in order to possibly treat cachexia, it is necessary to act on of pre-cachexia conditions, in the present work, we aimed to investigate the possibility that TMZ administration could interfere with the onset and progression of cachexia; therefore, to start the treatment concomitant with tumour inoculation was the best option. Future studies could be developed in order to understand if TMZ might have a curative action in milder models of cancer cachexia, starting to treat the animals when the tumour becomes palpable. Animal weight and food intake were recorded daily. The day of sacrifice (12 days after tumour transplantation), the animals were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation. The blood was collected by cardiac puncture and used to monitor glycaemia (Glucocard G-sensor; Menarini Diagnostics). The mice were then sacrificed by cervical dislocation and tibialis anterior (TA) and gastrocnemius (GSN) muscles were rapidly excised, weighed consecutively numbered and frozen in liquid N2-cooled isopentane, and finally stored at −80°C. When subsequent analyses are performed, the operator just knows the numbers but not the corresponding experimental groups.

Skeletal muscle function analysis

A forelimb grip strength blinded test was performed at Days 6 and 12 after tumour implantation by using a commercial digital grip strength metre (Columbus Instruments). Mice held by the tail were gently allowed to grasp a wire grid with the fore paws. The mice were then gently pulled by the tail until they released their grip. The force achieved by the mouse was recorded during three trials and averaged.

Immunofluorescence and cross-sectional area evaluation

Myofibre CSA measurement was performed on TA. Serial muscle sections (9 μm) were obtained from the midbelly region of the TA muscles that had been embedded in OCT. A CM1900 cryostat (Leica) at −20°C was used. Sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with an antilaminin (L9393) antibody and an antislow MyHC (M8421) from Sigma-Aldrich. The Alexa Fluor 488 anti-rabbit IgG (A11008) from Life Technologies was used as secondary antibodies. Nuclei were visualized with the DNA dye 40,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, and the samples were mounted in SlowFade Gold mounting media (Life Technologies). The images were acquired with a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope. In the stained muscle sections, automated CSA determination along the laminin-stained border of each fibre was evaluated by using Image J.46 Because errors in fibre border recognition might occur (i.e. either the fibres might not be recognized or several fibres/non-fibre regions might be interpreted as a single fibre), a manual correction of myofibre border misinterpretation was performed.

Histochemistry

Enzymatic staining for the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) activity was performed on TA cross sections. SDH incubation media were prepared by dissolving 1 mg/ml of nitrotetrazolium blue chloride and 27 mg/ml of sodium succinate in PBS.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Dissociation of samples was performed with Qiagen TissueRuptor, and RNA isolation was performed by using TRIreagent (Sigma-Aldrich) following the manufacturer's instructions. For RT-PCR, cDNA was synthesized with oligo-dT by adding 1 μg of RNA with GoScript Reverse Transcription System (Promega). Comparative real-time PCR was performed with the SYBR-green master mix (Promega) by using the Stratagene MX3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data were normalized to 18S, and a calibrator was used as internal control. Resulting data were analysed by the MX3PRO (v4.10), and fold change was determined by using the 2-ΔΔCT method.47, 48 All reactions were performed in triplicate. The following primers were used:

| 18S | Fw 5′-CCCTGCCCTTTGTACACACC-3′ |

| Rv 5′-CGATCCGAGGGCCTCACTA-3′ | |

| Atrogin-1 | Fw 5′-ATGCACACTGGTGCAGAGAG-3′ |

| Rv 5′-CCTAAGGTCCCAGACATCCA-3′ | |

| MyH | Fw 5′-CAAGTCATCGGTGTTTGTGG-3′ |

| Rv 5′-TGTCGTACTTGGGAGGGTTC-3′ | |

| PDK4 | Fw 5′-AAAGAGGCGGTCAGTAATCC-3′ |

| Rv 5′-TCCTTCCACACCTTCACCACA −3′ | |

| CTP1 | Fw 5′-CCCATGTGCTCCTACCAGAT-3′ |

| Rv 5′-CCTTGAAGAAGCGACCTTTG-3′ | |

| PGC1α | Fw 5′-GTCAACAGCAAAAGCCACAA-3′ |

| Rv 5′-TCTGGGGTCAGAGGAAGAGA-3′ | |

| Desmin | Fw 5′-GAGGTTGTCAGCGAGGCTAC-3′ |

| Rv 5′-GAAAAGTGGCTGGGTGTGAT-3′ | |

| MYH7 (MyHC I) | Fw 5′-TGCAGCAGTTCTTCAACCAC-3′ |

| Rv 5′-TCGAGGCTTCTGGAAGTTGT-3′ | |

| MYH2 (MyHC IIa) | Fw 5′-AGTCCCAGGTCAACAAGCTG-3′ |

| Rv 5′-GCATGACCAAAGGTTTCACA-3′ | |

| MYH1 (MyHC IIx/d) | Fw 5′-AGTCCCAGGTCAACAAGCTG-3′ |

| Rv 5′-CACATTTGGCTCATCTCTTGG-3′ | |

| MYH4 (MyHC IIb) | Fw 5′-AGTCCCAGGTCAACAAGCTG-3′ |

| Rv 5′-TTTCTCCTGTCACCTCTCAACA-3′ | |

| TNNI-1 | Fw 5′-GCACTTTGAGCCCTCTTCAC-3′ |

| Rv 5′-AGCATCAGGCTCTTCAGCAT-3′ | |

| TNNC-1 | Fw 5′-GCCTGTCCTGTGAGCTGTCT-3′ |

| Rv 5′-CAGCTCCTTGGTGCTGATG-3′ | |

| TNNT-1 | Fw 5′-ATCTGTGGACCCAGCCTTAG-3′ |

| Rv 5′-CTCTTCTCGCTCTGCCACC-3′ | |

| GLUT-4 | Fw 5′-GGCATGGGTTTCCAGTATGT-3′ |

| Rv 5′-GCCCCTCAGTCATTCTCATG-3′ | |

| Ins R | Fw 5′-CTCCTGGGATTCATGCTGTT-3′ |

| Rv 5′-GTCCGGCGTTCATCAGAG-3′ | |

| MCP-1 | Fw 5′-CTTCTGGGCCTGCTGTTCA-3′ |

| Rv 5′-CCAGCCTACTCATTGGGATCA-3′ | |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor | Fw 5′-CTGTGCAGGCTGCTGTAACG-3′ |

| Rv 5′-GTTCCCGAAACCCTGAGGAG-3′ |

Protein isolation and western blotting

Tissue samples from GSN and TA muscles were homogenized by using a GentleMACS Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec) and lysed in ice cold Cosper and Leinwand Myosin Extraction Buffer (300 mM NaCl, 0.1 M NaH2PO4, 0.05 M Na2HPO4, 0.01 M Na4P2O7, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM EDTA, and 1 mM DTT pH 6.5) or in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 130 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, and 0.1% sodium deoxycholate) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). A clear supernatant was obtained by centrifugation of lysates at 13 000 g for 20 min at 4°C. Protein concentration in the supernatant was determined by Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad). Aliquots of total cell lysates were then separated by SDS-PAGE by using Miniprotean precast gels (BioRad), and proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (BioRad) or to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (BioRad). Membranes were blocked 1 h at RT at 4°C with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20 and then probed by using the following antibodies directed against: Atrogin-1 (AP2041; ECMBiosciences), Laminin (L9393; Sigma-Aldrich), MyHC (MF20 recognizing all isoforms of skeletal muscle myosin heavy chain; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at the University of Iowa), slow MyHC (M8421; Sigma-Aldrich), fast MyHC (M4276; Sigma-Aldrich), Desmin (D1033; Sigma-Aldrich), α-tubulin (T5168; Sigma-Aldrich), pAkt (9271; Cell Signalling), Tom20 (sc-11415; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), TFAM (sc-23588; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) pFoxo 3A (9466S; Cell Signalling), PGC1α (AB3242; Millipore), βchain-ATP Synthase (MAB3494; Millipore), NDGR1 (3217; Cell Signalling), p-GSK3β (ser9) (ab75814; Abcam), p-RPS6 (2215S; Cell Signalling), p-p38MAPK (9216; Cell Signalling), VE cadherin (ab91064, Abcam), p-NFATc2 (ab200819, Abcam), and pACC (05-673 Millipore). The appropriate secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies from Jackson Immunoresearch were used in blocking solution for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by SuperSignal West Pico Chemioluminescent substrate kit (Pierce). Equal loading of samples was confirmed by α-tubulin (T5168; Sigma-Aldrich) or actin (A3853; Sigma-Aldrich) normalized and quantified by densitometry by using the ImageQuant TL software from GE Healthcare Life Sciences. The first WB was performed by an operator who was not aware of the group assignment, then in order to properly present data, samples were divided in the experimental groups and re-probed.

Cell culture and RNA extraction

Murine C2C12 skeletal myoblasts were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2 in an air-humidified chamber in high-glucose DMEM (Gibco) with glutamax, supplemented with 20% foetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Euro-Clone).49 As the cells approached confluency, the growth medium was replaced with a differentiation medium: DMEM supplemented with 2% horse serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The medium was changed every second day. On Day 4 of differentiation, myotubes were treated with TMZ (10 μM) and RNA was isolated with an RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen Instrumentation Laboratory, Milan, Italy), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Assessment of ΔΨm

ΔΨm was measured by using tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE, Molecular Probes) as previously reported.50 Murine C2C12 skeletal myoblasts treated or not with TMZ (10 μM) were incubated at 37°C for 15 min in media containing TMRE (50 nM). As a control for ΔΨm dissipation, cells were treated with 10 μM carbonyl cyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone. Cells were then rinsed in fresh medium and detached from the dish. TMRE fluorescence was detected by flow cytometry on a FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson).

Ex vivo measurement of skeletal muscle contractile properties

The contractile properties of both EDL and Soleus muscles excised from 3-month-old C57/BL6 mice were measured ex vivo as previously described.51 The muscle to be tested was vertically mounted in an oxygenated and temperature controlled chamber containing Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer. One end of the muscle was linked to a fixed clamp while the other was connected to the lever arm of an actuator/transducer (Aurora Scientific Inc. 300B). The isolated muscle was electrically stimulated, by means of two platinum electrodes, with 3 single 0.1 ms pulses and with 2 pulse trains at tetanic frequency (180 Hz for the EDL and 80 Hz for the Soleus). From the single pulse stimulations, we measured the twitch force and the kinetics parameters, namely, the time to peak, the half relaxation time, and the force derivative during both the contractile and the relaxation phases, while through the stimulation at the tetanic frequency, we measured the muscle maximum force and the resistance to isotonic fatigue. All the forces were then normalized with reference to the muscle cross sectional area52 to obtain the specific force values. Within this technique, we tested both the systemic and the direct effects of TMZ on skeletal muscles. In the first case, the animals were treated with 5 mg/kg TMZ once a day for 12 days. In the second case, each muscle was incubated in Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer containing TMZ for 15 min before being stimulated. Two different TMZ concentrations were tested: 10 and 100 μM.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed at least three times, unless otherwise indicated. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical differences between groups were verified by Student's t-test (2-tailed). *p < 0.05 was considered significant. For contractile properties measurements, differences in the mean of muscles incubated ex vivo with TMZ were assessed with one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test.

Results

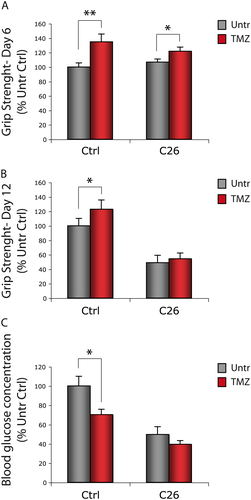

The metabolic reprogramming triggered by trimetazidine leads to grip strength increase in mice

Mice bearing the C26 colon carcinoma and healthy animals (controls; Ctrl) were treated with the metabolic modulator TMZ for 12 days. Grip strength was measured following 6 and 12 days of TMZ administration (Figure 1). In both Ctrl and C26-bearing mice, a significant increase in grasping strength was recorded after 6 days of TMZ treatment (Figure 1A); at day 12, this increase was persistent in Ctrl, but no more detectable in C26 hosts (Figure 1B). In line with our previous results obtained on C2C12 myotubes,43 blood glucose was reduced and the expression of the glucose receptor Glut 4 was increased in TMZ-treated Ctrl mice but not in the C26 hosts (Figures 1C and S1). The expression of Glut 4 increased also in C2C12 myotubes treated with TMZ (Figure S1).

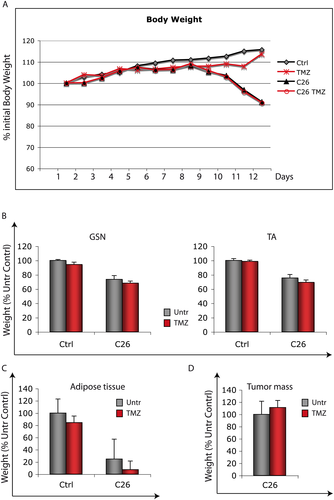

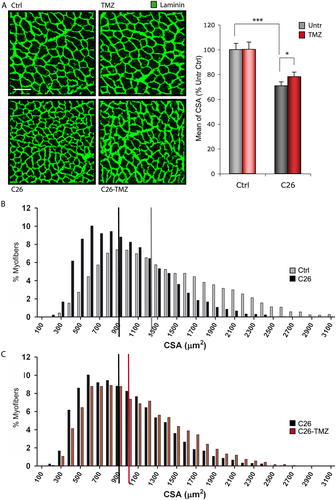

Trimetazidine partially restores myofibre cross-sectional area in C26-bearing mice

Based on our previous results showing that TMZ reduces myotube atrophy induced by TNFα and serum deprivation,43 we investigated the effect of this metabolic modulator on cancer-induced muscle wasting. The C26 tumour becomes palpable 5–6 days after implantation; the mice start losing weight at day 9 and are sacrificed at day 12, when the final body weight reaches about 75–80% of Ctrl animals (Figure 2A). TMZ did not prevent the decrease in body weight occurring in the C26-bearing mice (Figure 2A), nor did TMZ treatment reverse the decrease in TA, GSN weight, and adipose tissue mass recorded at 12 days after tumour implantation (Figure 2B and C). Moreover, tumour growth was not affected by TMZ (Figure 2D).

Conversely, TMZ partially protects myofibre CSA (Figure 3A and C; C26 vs. C26-TMZ) from the reduction associated to cancer (Figure 3A and B; Ctrl vs. C26). This is also reflected by the median value of CSA in the C26 hosts treated with TMZ, which was significantly higher compared with that of the untreated C26 bearers (Figure 3C; red vs. black bar). Of note, TMZ did not influence CSA in healthy mice (Figures 3A and S2; Ctrl vs. TMZ).

Trimetazidine triggers the activation of pathways involved in the maintenance of muscle mass

In order to evaluate the effect of TMZ treatment in the skeletal muscle also at the molecular level, we analysed the expression of genes associated to muscle mass maintenance such as those coding for myofibrillar proteins, namely, Desmin and MyHC. In the present study, we found that Desmin and MyHC mRNA levels increase in both the TA and the GSN of TMZ-treated C26 hosts compared with the untreated mice (Figure 4A). Because the two muscles were comparable, we performed further analysis, throughout this study, on one muscle type only.

Trimetazidine effects on the proteasomal degradative pathway were evaluated by measuring the transcript levels of the atrogenes Muscle Ring Finger protein 1 and atrogin-1. While the former tends to decrease (although not significantly) upon TMZ treatment in muscles of C26-bearing mice (Figure 4A), the latter does not significantly change (data not shown).

Finally, we also measured the levels of muscle Carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 transcript, a transporter of fatty acid into mitochondria, which we used as a marker of TMZ effectiveness. We observed that the muscle Carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 mRNA resulted up-regulated in TMZ-treated animals, possibly as a compensative response to the reduction of free fatty acid β-oxidation (Figure 4A).

Consistent with the data obtained for mRNAs, we found that, also at the protein level, the decrease of Desmin in muscle of C26-bearing mice is partially counteracted by TMZ treatment (Figure 4B). Accordingly, the protein levels of atrogin-1 increase in C26 hosts vs. Ctrl (likely contributing to the loss of muscle mass) while they are significantly reduced upon TMZ treatment (Figure 4B). In the attempt to shed some light on the signalling leading to myofibrillar protein up-regulation triggered by TMZ, we analysed some members of the PI3K/AKT-mediated molecular pathways, known to act on both protein degradation and synthesis. Along with atrogin-1 decrease, we found an increase in ribosomal protein S6 (RPS6)-phosphorylation (Figure 4B), this indicating activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 target S6 kinase (S6 kinase 1) and suggesting that protein synthesis is enhanced. We have found that TMZ treatment also enhances GSK3-β phosphorylation in Ctrl mice (Figure 4B). Such an enhancement cannot be observed in the C26 hosts; however, in these animals, pGSK3-β levels are higher than in Ctrl, so the possibility that a further increase is not achievable should be considered (Figure 4B and Penna et al.19). All these results suggest that the PI3K/AKT pathway is involved in the effects evoked by TMZ and indicate the activation of mechanisms counteracting muscle mass loss.

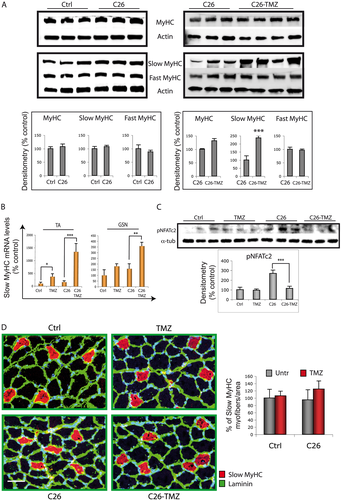

A shift towards a slow-twitch phenotype is triggered by trimetazidine

Total MyHC protein levels in TMZ-treated C26-bearing mice (Figure 5A) did not reflect the strong increase in MyHC gene expression (Figure 4A). Therefore, we decided to investigate if TMZ treatment was able to influence specific MyHC isoforms, which are differentially associated with myofibres having specific metabolic assessments. TMZ being a metabolic modulator, we set out to study the influence that this drug exerts on the metabolic features of the skeletal muscle, which is known to adaptively change in response to environmental alterations. Our analysis revealed that, in both GSN and TA muscles, TMZ resulted in increased slow MyHC protein levels, whereas fast MyHC and total MyHC did not appear to vary significantly (Figure 5A); no effect was found in healthy animals (data not shown). Similarly, TMZ triggers a robust increase of the slow MyHC transcript levels (Figure 5B). Interestingly, we have found that NFAT2c, whose transcriptional activity includes slow gene expression,53, 54 becomes dephosphorylated—this indicating activation and nuclear translocation—following TMZ treatment (Figure 5C).

The up-regulation of the slow MyHC isoform triggered by TMZ suggests a metabolic shift, from glycolytic to oxidative, within the myofibre, but also that the number of type I fibres could be increased. To assess this last hypothesis, we performed an immunofluorescence analysis on TA muscle cryosections, which indicated that the number of type I myofibres expressing the slow MyHC isoform (red in Figure 5D) tends to increase, though not significantly, in C26-TMZ animals.

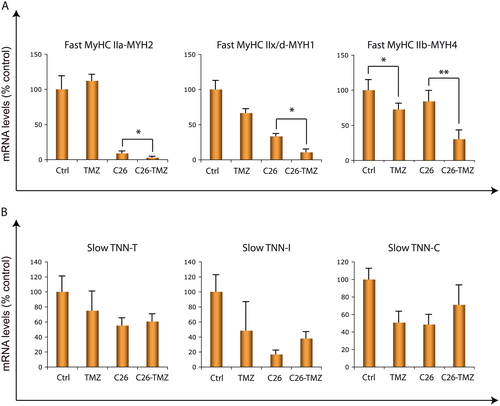

Three isoforms of fast MyHC have been described in rodents; type IIa, type IIx/d, and type IIb. We analysed these fast transcripts in TA and we observed that, in line with the increased expression of slow MyHC, their levels decrease in C26 hosts upon TMZ treatment (Figure 6A). A fibre-type conversion towards a more slow-twitch phenotype might also occur within type II fibres (e.g. from type IIb or type IIx/d towards type IIa) similarly to what happens upon exercise (reviewed by Gundersen54 and Lira55). For this reason, a more specific histological analysis will be part of further investigations. Lastly, we checked the expression levels of the slow isoforms of Troponin T, I, and C, some of which tend to increase, though not significantly, in TMZ-treated C26 animals (Figure 6B). In sum, these data support our hypothesis of a fast-to-slow twitch phenotype shift induced by TMZ in skeletal muscle.

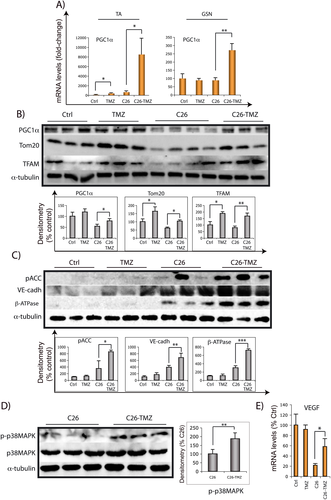

Trimetazidine promotes mitochondrial biogenesis, oxidative metabolism, and angiogenesis

Slow fibres are characterized by a high reliance on oxidative metabolism; therefore, an increase in slow fibre proportion following TMZ administration should imply an enhanced oxidative metabolism. To test this hypothesis, we assessed if TMZ might impact on mitochondrial biogenesis by measuring the expression of the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis PGC1α.56, 57 We observed that PGC1α mRNA was up-regulated upon TMZ treatment in both GSN and TA muscles of the C26 hosts (Figure 7A). Accordingly, PGC1α expression is higher in TMZ-treated C26 hosts vs. the untreated ones, also at the protein level (Figure 7B). PGC1α activation might be achieved by the phosphorylation and activation of the metabolic sensor AMPK.58 Due to technical problems in detecting pAMPK, we evaluated the phosphorylation of the acetyl CoA carboxylase, one of the main targets of AMPK, and we found that pACC increases upon TMZ treatment in C26-bearing mice (Figure 7C), indicating an increased activation of AMPK, which is consistent with PGC1α up-regulation. The increase of mitochondrial biogenesis was further investigated by evaluating the expression of the mitochondrial protein Tom20, the mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), and the β-subunit of the catalytic portion of mitochondrial ATP synthase, which, as expected, resulted definitively increased in TMZ-treated animals compared with the untreated ones (Figure 7B and C). Interestingly, PGC1α, Tom20, and TFAM protein levels decrease because of the disease (PGC1α; Ctrl vs. C26 p ≤ 0.01, Tom20; Ctrl vs. C26 p ≤ 0.01 and TFAM; Ctrl vs. C26 p ≤ 0.05) and such a reduction is partially rescued by TMZ (Figure 7B). Of note, mitochondrial biogenesis is controlled by several mechanisms, some of which may be independent on PGC1α; this explains the up-regulation of Tom20 and TFAM not associated to PGC1α increase in TMZ-treated Ctrl mice. Because PGC1α is a transcriptional co-activator, we also measured its protein levels in the nuclear fractions of GSN muscles, confirming the expression pattern observed in total lysates (data not shown).

As discussed in the succeeding texts, all our data suggest that the effects of TMZ administration to C26-bearing parallel those triggered by endurance exercise, as reported in the literature.59, 60 It has also been reported that exercise-induced mitochondrial biogenesis is largely controlled via PGC1α.61, 62, 59 To gain further insights into this similarity, we evaluated if the phosphorylation of p38MAPK, characterizing exercise and ex vivo muscle contraction,63, 64 is also activated by TMZ in C26 animals, and we found that the levels of p-p38MAPK are enhanced by TMZ in the C26 hosts (Figure 7C).

It is also known that exercise, as well as PGC1α overexpression, is able to trigger angiogenesis. As a further similarity among the effect of TMZ and exercise, we interestingly found that TMZ induces an increase of the vascular endothelial cadherin (Figure 7C) and, in line with this, we also revealed increased levels of the vascular endothelial growth factor—which is indeed a transcriptional target of PGC1α65—in skeletal muscle of TMZ-treated C26 mice (Figure 7E).

The experiments reported in the preceding texts show that TMZ triggers an increased mitochondrial biogenesis, likely reflecting an improved energy metabolism. To investigate this point, we evaluated the activity of the oxidative mitochondrial enzyme SDH in muscle cryosections. The percentage of oxidative fibres stained for SDH activity significantly increased in the C26 hosts upon TMZ treatment, while no difference was detected in TMZ-treated Ctrl mice (Figure 8; histogram on the left). The specific analysis of regions characterized by mixed glycolytic and oxidative fibres showed a trend towards an increased percentage of SDH-positive fibres also in TMZ-treated Ctrl mice (Figure 8; histogram on the right).

Finally, we measured the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) in C2C12 myoblasts treated or not with TMZ; TMRE staining revealed an increase of ΔΨm triggered by TMZ, suggesting an increased mitochondria metabolism (Fig S3).

Autophagy and apoptosis are not altered by trimetazidine in C26-bearing mice

Because we have found an effect of TMZ on autophagy in vitro,43 we investigated the occurrence of autophagy and apoptosis in muscles upon metabolic modulation by TMZ. We evaluated both LC3 and p62 protein levels (Figure 9A), and we found that LC3-I decreases and LC3-II increases in C26 hosts (Ctrl vs. C26 p ≤ 0.01 for both LC3-I and LC3-II), indicating an increased autophagy in cancer cachexia, as previously reported.66 However, we found no significant variation of LC3-I and LC3-II levels associated with TMZ treatment; this demonstrates that, in contrast to our previous in vitro data, TMZ does not interfere with autophagy in vivo. This hypothesis is further supported by the observation that TMZ did not influence p62 expression levels in C26-bearing mice, despite p62 up-regulation found in Ctrl mice. To monitor apoptosis, we analysed both Caspase-3 and PARP cleavage67 in GSN lysates but observed no influence of TMZ in C26-bearing mice (Figure 9B).

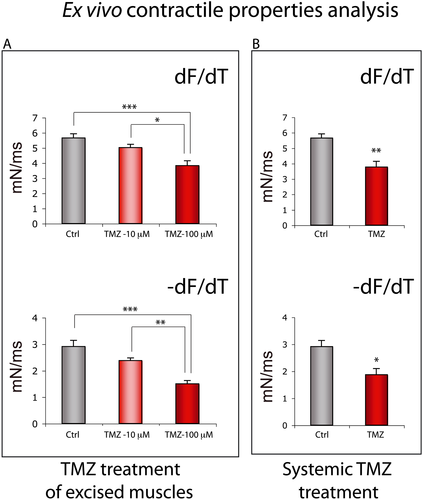

Skeletal muscle is a direct in vivo target of trimetazidine

Finally, in order to study the specific effect of TMZ on skeletal muscle and to exclude the occurrence of an indirect role mediated by the known beneficial action of TMZ on cardiac function, we performed an ex vivo analysis on isolated hind limb muscles exposed to TMZ (see 2 section). Despite no significant effect being detected in the Soleus (data not shown), we observed a direct dose-dependent effect of TMZ on the fast EDL muscle (Figure 10). TMZ triggered a change of the EDL contraction kinetics inducing a shift towards a slow-twitch contractile phenotype, with the kinetics being significantly slower in the EDL treated with 100 μM TMZ compared with untreated EDL muscles (Figure 10A and B; df/df and −df/dt). The contraction rate of treated muscles was about 32% lower in comparison with the untreated ones (Figure 10A; df/df), and the relaxation rate was almost halved (Figure 10A; −df/df). This change towards a slow contractile phenotype was also found in the EDL excised from mice systemically treated with TMZ as shown in Figure 10B (df/df and −df/dt). This kinetic slowdown is partly explained by the decreased twitch force generated following both TMZ treatment of excised muscles and systemic TMZ treatment (Table 1; Ftw_sp), although the specific tetanic force and the resistance to fatigue did not significantly change upon TMZ treatment (Table 1; F0_sp and Tfat). However, also considering the reduced twitch force, TMZ has a neat effect on the decrease of relaxation time (Figure 10A; −df/df) and on the kinetic slowdown. These experiments confirm that TMZ has the ability to directly act on skeletal muscle and to modify its contractile kinetics.

| CTR | TMZ 10 μM | TMZ 100 μM | TMZ systemic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ftw_sp | 24.7 ± 1.39 | 21.1 ± 1.29 | 16.9 ± 1.36*** | 17.4 ± 1.93* |

| F0_sp | 134.2 ± 9.41 | 122.5 ± 15.03 | 109.6 ± 5.24 | 102.9 ± 17.20 |

| Tfat | 21.7 ± 1.45 | 23.1 ± 1.12 | 24.7 ± 1.18 | 23.0 ± 1.37 |

- * p ≤ 0.05.

- *** p ≤ 0.001.

Discussion

The present study highlights the ability of the metabolic modulator TMZ to stimulate adaptive mechanisms in the skeletal muscle. We mainly found that, similarly to the effect observed in aged mice,68 TMZ triggers a significant increase in grasping strength in C26 hosts and healthy mice, which is a more relevant achievement than the increase in muscle mass not associated to strength increase. In addition, in agreement with our previous data obtained in vitro,43 we found that TMZ partially protects from the reduction of myofibre CSA occurring in cachectic mice. Such a protection relies on the activation of pathways known to increase protein synthesis and to reduce protein degradation, therefore enhancing skeletal muscle plasticity aimed at counteracting muscle wasting.

Moreover, our study revealed that, in the skeletal muscle of the C26 hosts, TMZ induces a fast-to-slow shift of metabolic and contractile myofibre properties, closely resembling that triggered by endurance exercise.54, 69 In particular, TMZ favours a shift towards a slow-twitch/oxidative metabolism in both GSN and TA, which are predominantly fast-twitch muscles mainly containing glycolytic fibres. Accordingly, fast EDL muscles incubated ex vivo in the presence of TMZ assume a contractile response that resembles that of slow muscles. Interestingly, three-dimensional muscles engineered by using primary myoblasts isolated from predominantly fast TA and slow Soleus adopt the myosin isoform profile and the contractile and metabolic properties of their parent muscle (respectively fast and slow).70, 33, 71, 31 We observed that the isoform profile of the predominantly fast TA before TMZ treatment (low levels of slow MyHC and high levels of fast MyHC IIb and IIx/d) was similar to that of the engineered TA, while after TMZ treatment, it resembled that of the slow Soleus construct. Moreover, the fast MyHC IIa and the slow isoforms of the three Troponin subunits (TNN-T, I, and C) do not vary much between TA and Soleus constructs; likewise, they do not change very much upon TMZ treatment.33 All these analogies support our finding that TMZ is able to mediate a fast-to-slow shift of myofibre contractile proteins. Typically, fast fibres are more susceptible to atrophy than slow ones, while the latter are more resistant to stress stimuli.72 We therefore hypothesize that the fast-to-slow shift triggered by TMZ in cachectic animals might support an adaptive attempt to face the adverse conditions caused by tumour growth.

Because MyHC isoforms are involved in determining the rate of muscle contraction in vivo, our ex vivo data (indicating a TMZ-induced switch towards a slowing contractility) are in accordance with the increased slow MyHC content and oxidative metabolism we have found in vivo upon TMZ injection. However, TMZ ability to modify the contractile properties of the EDL upon 20 min of ex vivo incubation indicates that, besides the transcriptional and/or translational regulation of both specific contractile and mitochondrial proteins, this metabolic modulator also exerts rapid effects, possibly due to ionic (e.g. Ca2+) flux modulations. Consistent with this hypothesis is the observation that TMZ rapidly increases ΔΨm in myoblasts. ΔΨm is closely related to Ca2+ and other ion fluxes, able to influence myofibre contractile properties. This point deserves further investigation, however.

In line with the fast-to-slow shift of the contractile apparatus exerted by TMZ, we also found that PGC-1α, a major mediator of the phenotypic adaptation induced by exercise, becomes overexpressed upon TMZ administration. Notably, PGC-1α is mainly expressed in slow muscles and plays a key role in slow fibre specification.56, 57, 61, 62, 59 Moreover, PGC-1α effects include the promotion of mitochondrial oxidative metabolism on which slow fibres mostly rely. Accordingly, we found an increase of both mitochondrial content and SDH activity in the skeletal muscle of TMZ-treated C26 hosts Finally, PGC-1α overexpression has been shown to exert anti-atrophic effects73 and to increase glucose-uptake, consistently with the results we report in TMZ-treated mice.

On the whole, the effects of TMZ administration to C26-bearing mice share several features with endurance exercise, such as increased muscle strength, fast-to-slow phenotype shift, PGC1α overexpression, increased capillarity density, and oxidative metabolism up-regulation.59,74 In this regard, previous data obtained in our laboratories show that, similarly to TMZ, endurance exercise can improve muscle strength without modifying muscle mass in mice bearing the Lewis lung tumour. Such an improvement is associated with increased oxidative metabolism, as suggested by restoration of mitochondrial morphology and SDH activity.75 For these reasons, we propose that TMZ might act as an ‘exercise mimetic’, in line with our recent findings showing that TMZ improves exercise capacity in ageing.68 Other metabolic remodelling agents such as GW1516 and AICAR have been reported to mimic some of the effects of exercise aimed at achieving the best metabolic energy efficiency.76-78

Trimetazidine administration to tumour-bearing mice resembles endurance exercise also at the molecular level. Contraction and exercise have been shown to activate MAPK-dependent signal transduction pathways.79, 64 In particular, p-p38MAPK phosphorylates and activates PGC1α as well as some PGC1α-related transcription factors (e.g. ATF2 and MEF2).55 Of interest, p38MAPK phosphorylation has been reported during ex vivo muscle contraction,63, 64 likely contributing to mediate changes in muscle gene expression in response to exercise. In the present study, we show increased levels of phosphorylated p38MAPK in TMZ-treated C26-bearing mice, which is in line with the increased PGC1α expression and corroborates once more the analogies between TMZ treatment and exercise effects on skeletal muscle.

For the sake of correctness, we must acknowledge some limitations in the execution of the present study; an exercise group was not included, based on the fact that there are several data reporting the effects of exercise in the skeletal muscle59 and that we previously published results showing that at least some of the modulations induced by exercise in mice bearing the LLC also occur in TMZ-treated C26 hosts.75 Moreover, simply for technical reasons, we did not have the possibility to evaluate total physical activity in treated and untreated animals, as well as to perform mitochondrial respirometry on fresh muscles, which would have significantly improved the conclusions of this study. Finally, the C26 tumour is very aggressive; however, the possibility that some TMZ effects are lost because of tumour aggressiveness—including the absence of an effect on muscle wasting—cannot be ruled out. Consistent with this hypothesis is the observation that TMZ-induced grip strength improvement, evident after 6 days of treatment, is lost afterwards (12 days after tumour transplantation), when mice health status is severely compromised. Strikingly, a recent report by Fukawa and collaborators80 strongly supports our data; the authors showed that excessive fatty acid oxidation occurring in cancer cachexia induces muscle atrophy and that pharmacological blockade of fatty acid oxidation by etomoxir can increase muscle mass in animal models. Differently from our study, the authors used stable cachexia animal models in which cachexia is induced after several weeks of cancer cell inoculation.

In conclusion, our data show that TMZ administration partially counteracts the reduction of myofibre CSA typical of cachectic mice and induces some of the benefits achieved through exercise, including fast-to-slow myofibre phenotype shift, PGC1α up-regulation, oxidative metabolism, and angiogenesis enhancement and grip strength increase. Adaptation to exercise training also includes increased expression of key metabolic genes and increased sensitivity to insulin.81 Consistently, here, we found that TMZ reduces glycaemia. Improvement of glucose utilization, reduction of glycaemia as well as of glaciated haemoglobin by TMZ have also been observed in humans in diabetic patients,82, 83 which makes this drug potentially useful also for the treatment of diabetes. The effects of TMZ observed in the presence of a highly aggressive challenge (the C26 tumour) further support the relevance of these results and suggest a possible repositioning of this drug in milder skeletal muscle atrophy conditions where it could be included in a multimodal therapeutic approach. Moreover, the ‘exercise-like effects’ of TMZ may suggest the use of TMZ in contexts in which exercise is beneficial but not applicable, such as in case of bed rest and immobilization, hospitalization due to orthopaedic surgery, regenerative impairment, sarcopenic obesity, or ageing.60, 84 Such an opportunity is more and more likely because TMZ has already been approved for the clinical use. Moreover, TMZ has a high safety profile compared with the severe hepatotoxicity reported for the etomoxir recently used to demonstrate that free fatty acid oxidation could be targeted to prevent cancer-induced cachexia.80 Although recapitulating the complexity of all the molecular effects with a single ‘exercise pill’ is unlikely to be achieved,85 pharmacotherapies that replicate at least some exercise-induced effects could be useful when there is a physiologically low response of muscle to exercise or when exercising is not possible.

Ethical standard statement

Experimental animals were cared for in compliance with the Italian Ministry of Health Guidelines (no 86609 EEC, permit number 106/2007-B) and the Policy on Human Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH 1996). The experimental protocol was approved by the Bioethical Committee of the University of Turin and by the Italian Ministry of Health, Italy, and has therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank L. Gatta, C. Nicoletti, and L. Vitiello for technical support and MW Bennett for the valuable editorial work. We are grateful to M. Caruso and N. Filigheddu for their helpful discussion. The authors certify that they comply with the ethical guidelines for authorship and publishing of the Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle.86

This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health for Institutional Research and grant Ricerca Finalizzata (RF) 2010-2318508 to Elisabetta Ferraro.

Conflict of interest

Francesca Molinari, Fabrizio Pin, Stefania Gorini, Sergio Chiandotto, Laura Pontecorvo, Emanuele Rizzuto, Simona Pisu, Antonio Musarò, Fabio Penna, Paola Costelli, Giuseppe Rosano, and Elisabetta Ferraro declare that they have no conflict of interest.