Daily Parenting and Adolescent Maladjustment: A Two-Wave Multi-Informant Daily Diary Study Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic

ABSTRACT

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic posed major challenges to parent–adolescent relationships under global stressors. Scant research has examined changes in the daily links between parenting behaviors and adolescent maladjustment before and after the onset of the pandemic. This study investigated the within-day associations between two parenting behaviors—positive parenting and psychological control—and three adolescent maladjustments—conduct problems, emotional problems, and negative affect—before and during COVID-19 through a two-wave multi-informant month-long daily diary study.

Methods

A total of 3041 daily observations from 30 parent–adolescent dyads collected in Canada (adolescents: M = 14.3, 39% female, 42% White; parents: M = 43.5, 72% female, 42% White) were assessed before (2019, nobservation = 778 and 772, for adolescents and parents, respectively) and during (2022, nobservation = 737 and 754) the pandemic.

Results

Positive parenting and conduct problems decreased, while emotional problems increased from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic. Multi-level modeling showed that positive parenting was negatively linked with conduct problems and negative affect on the same day, whereas psychological control was positively linked with conduct problems and negative affect on the same day. Based on adolescent-reports, the onset of the pandemic suppressed the negative relation between positive parenting and negative affect, and amplified the positive relation between psychological control and emotional problems.

Conclusions

These findings provide crucial evidence for changes in the daily links between parenting behaviors and adolescent maladjustment from before to during the pandemic. Family-based interventions should target daily parenting behaviors during periods of stress and uncertainty to promote adolescent adjustment.

1 Introduction

Parenting behaviors play a significant role in supporting adolescent development (Pinquart 2017) and have long-lasting impacts into adulthood (Smetana and Rote 2019). Adolescence is an important developmental period characterized by rapid biological and psychological changes with accompanied elevated risks for maladjustment that is linked to both short- and long-term adverse outcomes, such as lower school performance and worse future career development (Steinberg and Morris 2001). The COVID-19 pandemic posed multiple threats to parent–child relationships and the well-being of parents and children due to challenges related to economic (e.g., unemployment) and social (e.g., social restrictions) disruptions (Prime et al. 2020). With the significant changes and challenges faced by parents and adolescents, adaptive family processes such as positive parenting behaviors and cohesive parent–adolescent relationships are crucial assets that could promote the well-being of all family members (Prime et al. 2020). Consequently, there has been a surge of interest in studying the parent–adolescent dyad within the context of COVID-19 pandemic. Leveraging data collected before and during the COVID-19 pandemic through a two-wave multi-informant month-long daily diary design, this study aimed to explore how the pandemic may have changed the daily links between parenting behaviors and adolescent maladjustment.

1.1 Parenting and Adolescent Adjustment During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The principle of interdependence from the family systems theory (Cox and Paley 2003) posits that family members are interconnected and interdependent, making behaviors and relationships of family members interdependent accordingly. Informed by this principle, the COVID-19 family disruption model (Prime et al. 2020) proposes that stressors affecting one family member (e.g., parent) may disrupt the entire family system, thereby affecting the adjustment of other family members (e.g., spouses, children). Moreover, the family stress model suggests that parents undergoing elevated levels of stress tend to rely on maladaptive parenting behaviors, such as harsh parenting and psychological control (Masarik and Conger 2017). Stressors originated from the pandemic are key risk factors for maladaptive parenting behaviors and child maladjustment (Brown et al. 2020; Freisthler et al. 2022; Prime et al. 2020). For instance, in a four-wave study during the pandemic with 2–3 weeks between each wave, pandemic-related stress at wave 1 was linked to negative parenting at wave 3 through elevated maternal psychological distress at wave 2, which subsequently increased children's externalizing problems at wave 4, supporting the cascading influences of the pandemic on parenting and child maladjustment (Shelleby et al. 2022). Similar changes in parenting behaviors and the associated changes in child or adolescent maladjustment are evident in two recent systematic reviews (Campione-Barr et al. 2024; Shoychet et al. 2023). Nonetheless, there are also multiple mixed or inconsistent findings in the literature, such as the decline in adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms from before to after the onset of pandemic (Campione-Barr et al. 2024; Mlawer et al. 2022; Penner et al. 2021). Therefore, it is necessary to further examine related changes since the onset of the pandemic to elucidate adaptive family processes for promoting adolescent adjustment.

1.2 Changes in Parent–Adolescent Dynamics Before and After the Onset of Pandemic

According to the COVID-19 family disruption model (Prime et al. 2020; Shoychet et al. 2023), positive parenting behaviors, a collection of parenting behaviors characterized by warmth, affection, praise, and compliment, can function as a protective factor, whereas controlling parenting behaviors, behaviors that intrude and limit adolescents' autonomy and independency through physical or emotional manipulations, can pose risks for adolescent maladjustment during the pandemic. However, pandemic-related factors (e.g., social restrictions) could change the effects of parenting behaviors (Shoychet et al. 2023). That is, the pandemic possibly could moderate the associations between parenting behaviors and adolescent adjustment. An investigation into these changes would inform how the pandemic may have shifted parent–adolescent dynamics.

According to a recent systematic review, positive parenting behaviors did not consistently promote adolescent adjustment during the pandemic as compared to pre-pandemic research findings (Shoychet et al. 2023). For instance, in a two-wave study among Latinx adolescents before and after the onset of COVID-19, parental support did not mitigate the impact of various pandemic stressors on adolescent internalizing symptoms (Roche et al. 2022). Therefore, despite the documented protective effects from pre-pandemic literature (Janssens et al. 2021; Soenens et al. 2007, 2015), positive parenting behaviors may not be as beneficial for adolescents to the same extent during the pandemic (Roche et al. 2022). On the other hand, how one specific negative parenting behavior—psychological control—and its link to adolescent maladjustment may have changed is less clear (Campione-Barr et al. 2024). Although direct evidence is lacking, given the general increase in maladaptive parenting behaviors and their salient impacts on adolescents after the onset of COVID-19 pandemic (Shoychet et al. 2023), psychological control may be similarly or even more influential on adolescent maladjustment during the pandemic. Thus, it is plausible that the effects of parenting behaviors (whether positive or negative) on adolescent adjustment could have changed during this special time period.

1.3 Daily Parent–Adolescent Dynamics During the Pandemic

Parent–adolescent dynamics unfold across different timescales and a surge of recent studies have begun to investigate the fluctuations of parenting behaviors as well as their links to adolescent adjustment on a daily level using intensive longitudinal data (e.g., Xu and Zheng 2023; Zheng et al. 2024a, 2024b). Family processes observed in conventional longitudinal studies (e.g., annual assessment) may not hold on a micro timescale (e.g., days; Keijsers et al. 2022; Xu and Zheng 2022; Zheng and Goulter 2024). In a recent review of longitudinal parenting studies using various designs, many mixed or inconsistent findings linking parenting behaviors with adolescent adaptations are evident across different measurement time intervals, with the most typical time intervals being 12 months on a macro timescale and 1 day on a micro timescale (Boele et al. 2020). Therefore, focusing on only one timescale may lead to biased or erroneous conclusions regarding family processes on another timescale. Instead, well-designed studies integrating multiple timescales, such as measurement burst designs (research designs that involve repeated bursts of intensive assessments over longer time intervals; Shen et al. 2024; Sliwinski 2008), could offer us a more refined picture of short-term parent–adolescent relationships in daily lives as well as their long-term changes over years (e.g., pre- and during-pandemic; Boele et al. 2020; Zheng and Goulter 2024). Despite the surge of recent efforts to unpack daily parenting processes (Boele et al. 2020; Keijsers et al. 2022; Xu and Zheng 2022, 2023), much less is done in the context of COVID-19.

To this end, a few studies have examined daily parenting processes during COVID-19 with the daily diary design, especially focusing on positive parenting as a potential buffer for the pandemic. For instance, in a 14-day study among a group of US adolescents, adolescent-reported parental support was related to higher same-day and next-day adolescent positive affect, and lower same-day adolescent negative affect, demonstrating the protective effect of parental support against adolescent maladjustment during the pandemic (Wang et al. 2021). A month-long study among US adolescents similarly showed a same-day link between adolescent-reported parental warmth and higher positive affect, as well as lower negative affect and misconduct (Wang et al. 2022). In a 21-day German study, parent-reported daily parental autonomy-supportive parenting was related to increased family cohesion and better well-being of both parents and 6- to 19-year-old children on the same day (Neubauer et al. 2021). In contrast, another 21-day German study demonstrated that parent-reported daily negative parent–child interactions were related to lower affective well-being of parents and children on the same day (Schmidt et al. 2021). Relatedly, a 14-day study in Netherlands showed that mothers reported less disruptive child behaviors on days when they had more positive involvements in joint activities, but more disruptive child behaviors on days when they used more harsh discipline (Leijten et al. 2024). These pandemic studies collectively highlight the vital role of daily parenting behaviors in adolescent adjustment during the pandemic. Therefore, despite the potentially weakened effect during the pandemic, positive parenting behaviors should not be overlooked, as they can still be important assets and protective factors for children, especially given the lack of social support and the resource-limited family environment during the pandemic (Prime et al. 2020).

There is scarce knowledge of the changes in daily parent–adolescent dynamics before and after the onset of pandemic. As two notable examples, Janssens et al. (2021) leveraged two-wave, 6-day experience sampling data from pre- to mid-pandemic and found decreased adolescents-reported daily irritability and increased loneliness over time. Moreover, adolescents with lower paternal relationship quality also reported higher daily irritability in both waves, and both paternal and maternal relationship quality buffered against the increase in loneliness from before to during the pandemic. In another two-wave, 14-day ecological momentary assessment study of parent–adolescent dyads’ daily affective well-being, parents reported decreased daily negative affect from before to during the pandemic, yet there were no significant changes in adolescent self-reported daily positive or negative affect, either parent- or adolescent-reported parenting behaviors (warmth and criticism; Janssen et al. 2020). While these early findings supported the pandemic as a turning point that shifted daily parent–adolescent dynamics, a clear picture depicting the systematic patterns of change from before to during the pandemic cannot be drawn. How and what daily associations between parenting behaviors and adolescent adjustment may have changed remains an open question, and further investigations using intensive longitudinal data from both parents’ and adolescents’ perspectives are necessary (De Los Reyes and Ohannessian 2016; Li and Zheng 2025). The timing of data collection should also be considered. In both Janssen et al. (2020) and Janssens et al. (2021), the data collection took place approximately 1 month into the lockdown in March and April 2020, during which time changes in parenting and adolescent adjustment might not yet be evident.

1.4 The Current Study

This study explored the impact of the pandemic on daily parent–adolescent dynamics. We sought to understand the changes in the levels as well as the associations between two parenting behaviors—positive parenting and psychological control—and three adolescent maladjustments—conduct problems, emotional problems, and negative affect—before and during COVID-19 through a two-wave measurement burst design. We used positive parenting as a broad construct representing a warm and cohesive family dynamic. We focused on psychological control as the negative parenting behavior as it is commonly examined in family research as a risk factor for adolescent autonomy development (Campione-Barr et al. 2024). We examined both affective (i.e., emotional problems and negative affect) and behavioral (i.e., conduct problems) maladjustment outcomes in adolescents to elucidate the links between family processes and adolescent adjustment more completely across multiple domains. As a part of normal developmental process, children in middle and late adolescence typically become increasingly independent and shift more of their time and attention from family members to peers (Smetana and Rote 2019). However, autonomy and independency could be disrupted by the social restrictions during the pandemic, which may leave stronger impact on older adolescents than younger children (Campione-Barr et al. 2024). Therefore, we focused on families with children in their middle and late adolescence to examine the ways in which family dynamics shifted to face these changes and challenges. To get a more comprehensive picture, we also took a multi-informant approach by gathering both adolescents' and parents' reports to see whether congruent or incongruent patterns can be found.

We hypothesized that (1) positive parenting would decrease from before to during the pandemic, whereas psychological control and various adolescent maladjustment would increase from before to during the pandemic (H1); (2) positive parenting would be negatively associated with adolescent maladjustment on the same day, whereas parental psychological control would be positively associated with adolescent maladjustment on the same day (H2). In addition, two exploratory hypotheses were tested: (3) the pandemic possibly could suppress the protective effect of positive parenting on adolescent maladjustment and exacerbate the pernicious effect of psychological control on adolescent maladjustment (H3), and (4) parent- and adolescent-reports could potentially yield different patterns of results (H4).

2 Methods

2.1 Participants and Procedure

A total of 99 parent–adolescent dyads were initially recruited from 2019 to 2020 in Canada for a month-long daily diary study on daily parenting behaviors and adolescent adjustment. Participants were then followed up with the same assessment procedure including the same core constructs and measurements in 2022 from April to July. During this time, Canada just experienced the peak of the fifth pandemic wave and was in the early stage of gradually lifting social restrictions (e.g., resumption of some school and social activities/events) in different provinces. All restrictions were eventually removed in October 2022, representing the end of the pandemic lockdown (Public Health Agency of Canada 2022). As such, the data were collected in the transitioning phase into post-pandemic era, during which time parents and children still had more shared time together at home than pre-pandemic and many parents still worked from home, before all social restrictions were lifted, and a reasonable time point to assess the changes in parent–child dynamics under the impact of the pandemic when mandatory policies and restrictions have been effective for a long time. Specifically, participants were recruited through local and provincial school systems, community outreach, family service centers, and internet recruitment. Interested participants who reached out to the research team provided consent/assent online. For the purpose of the analysis, only participants who completed their daily assessments before the onset of COVID-19 in Canada (March 11, 2020) were included (86 dyads). Participants who only participated in the first wave were also removed from the analysis, leaving a final analyzed sample of 30 parent–adolescent dyads.

At wave 1, adolescents' ages ranged between 12 and 17 years old (M = 14.26, SD = 1.74, 39% female, 12 White, 11 Asian, 1 Black, 4 Multiracial, 1 Latino, 1 Others). Parents' ages ranged between 34 and 60 years old (M = 43.5, SD = 6.05, 72% female, 16 White, 12 Asian, 1 Multiracial, 1 Latino). Parental personal annual income ranged from below $35,000 (five parents) to above $65,000 (11), with 5 between $35,000 and $45,000, 1 between $45,000 and $55,000, and 8 between $55,000 and $65,000. 20 parents received Bachelor's degree or equivalent, and six parents received Master's degree or above, 3 parents received High school or equivalent diploma, and 1 parent received Middle school diploma or below. In wave 1, adolescents and parents on average reported 25.9 and 25.7 daily observations, respectively (ns = 778 and 772). In wave 2, adolescents and parents on average reported 24.6 and 25.1 daily observations, respectively (ns = 737 and 754). Attrition analyses revealed that participants retained in wave 2 did not differ in age, sex, ethnicity-race, income, education level, and the daily average scores in all core variables from those who only participated in wave 1.

In each wave, participants first completed an online baseline survey (~45 min) and subsequently a month-long daily diary survey (~6–7 min each day) containing the same core constructs and measurements. We took the end-of-day approach, where parents and adolescents reported after 5 pm and before bedtime reflecting on how they felt and what they have experienced on that day. Data were collected using the survey tool RedCap (Harris et al. 2009). Parents and adolescents who completed the 30-day daily survey received a $45 e-gift card, respectively, as a compensation for their participation. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at University of Alberta.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Positive Parenting

Parents and adolescents reported daily positive parenting (0 = no, 1 = yes) on three items rephrased accordingly for parents and adolescents (e.g., “You let your child know when he/she did a good job with something,” “You complimented your child after he/she did something well,” “You praised your child after he/she behaved well.”) using the positive parenting items from the short form of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (Elgar et al. 2007). Item scores were summed to represent daily positive parenting. Ordinal ωs indicated good reliability at within-person (ωs = 0.87–0.98) and between-person (ωs = 0.86–0.97) level for both parent- and adolescent-reports across waves.

2.2.2 Parental Psychological Control

Parents and adolescents answered 17 questions on daily parental psychological control modified from the Psychological Control Item Bank (Olsen et al. 2002) rated on a 3-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat true, 2 = very true). The scale consists of five subdimensions: constrain verbal expressions (“Interrupt me when I was speaking,” three items), invalidate feelings (“Would have liked to tell me how to feel or think about things,” one item), erratic emotions (“Lost temper easily at me,” two items), love withdrawal (“Avoided looking at me when I disappointed my parent,” four items), and guilt induction (“Told me of all things my parent has done for me,” seven items). All item scores were averaged to form a composite score, with higher scores representing higher levels of parental psychological control on that day. Ordinal ωs indicated good reliability at within-person (ωs = 0.92–0.95) and between-person (ωs = 0.87–0.90) level for both parent- and adolescent-reports across waves.

2.2.3 Conduct and Emotional Problems

Parents and adolescents reported adolescents' daily conduct and emotional problems with the 5-item conduct problem subscale (e.g., “I get very angry and often lose my temper.”) and the 5-item emotional problem subscale (e.g., “I am unhappy, depressed, tearful.”) from the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman et al. 1998) on a 3-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat true, 2 = certainly true) on how well these items described adolescents on that day. The psychometric properties of SDQ regarding factor structures, reliability, and validity have been validated in daily diary research (Zheng and Zheng 2024). Within each subscale, item scores were averaged to form a composite score representing conduct and emotional problems on that day. Ordinal ωs indicated good reliability at within-person (ωs = 0.72–0.89) and between-person (ωs = 0.90–0.93) level for both parent- and adolescent-reports across waves for conduct problems, and similarly for emotional problems at within-person (ωs = 0.78–0.98) and between-person (ωs = 0.91–0.99) level for parent- and adolescent-reports across waves.

2.2.4 Negative Affect

Parents and adolescents reported adolescents' daily negative affect (e.g., “upset,” “ashamed”) with five items selected from the short form Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (Thompson 2007) on a 5-point scale (0 = very slightly or not at all, 1 = a little, 2 = moderately, 3 = quite a bit, 4 = extremely) on how well these adjectives described adolescents on that day. The item averaged score was used to indicate daily negative affect. Ordinal ωs indicated good reliability at within-person (ωs = 0.83 − 0.95) and between-person (ωs = 0.81–0.97) level for both parent- and adolescent-reports across waves.

2.3 Analytic Strategy

All analyses were performed in Mplus 8.3 (Muthén and Muthén 1997–2019). Multilevel structural equation models (MSEM) with Bayesian estimation were constructed to examine the hypothesized associations. Bayes estimation generates less biased estimates in small samples (especially at the between-person level) with missing data (Asparouhov et al. 2018). Model convergence was assessed using the Potential Scale Reduction (PSR) statistic, trace plots, and autocorrelation plots (Hamaker et al. 2023). Within-person level paths were specified to investigate the daily fluctuations of parenting behaviors and adolescent maladjustment relative to their within-person average level as well as their within-day links. Autoregressive paths were estimated for adolescent maladjustment to control for previous day's lagged effects. Random intercepts of outcome variables were estimated at the between-person level after controlling for demographic variables (age, sex, ethnicity-race). Random slopes of each autoregressive paths and within-day associations were specified. In addition, moderation effects of the pandemic (0 = before pandemic/wave 1 vs. 1 = during pandemic/wave 2) were examined. At the within-person level, interaction terms were formed between the predictors (i.e., parenting behaviors) and the moderator (i.e., pandemic). The outcome variables were regressed on the predictors, the moderator, and the interaction term. Random slopes were also estimated for the main effects and the moderation effects of the pandemic on adolescent maladjustment. When significant, linear trend and weekend effects were controlled for potential linear changes as well as weekend versus weekday effects on adolescent outcomes, respectively. Specifically, the weekend/weekday effect was controlled as a dummy variable at the within-person level, which was used to assess whether there were significant differences in the measured variable between weekdays or weekends. Give the modest correlations between baseline variables with the main variables of interest, as well as the small sample size at the between-person level, we did not include any other baseline variables in our main analyses.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive Statistics

Within- and between-person level correlations were estimated for all key variables reported by adolescents (Table 1) and parents (Table 2). All outcome variables were positively correlated with each other for both parent- and adolescent-reports at both within-person (rs = 0.25 − 0.58, ps < 0.001) and between-person (rs = 0.41 − 0.89, ps < 0.05) levels. At the within-person level, parental psychological control was positively correlated with all outcome variables (rs = 0.11 − 0.29, ps < 0.001) for both parent- and adolescent-reports. Positive parenting was negatively correlated with all outcome variables in parent-reports (rs = −0.06 – −0.08, ps < 0.05), but not in adolescent-reports. The two parenting behaviors were negatively correlated with each other only at the within-person level in adolescent-reports (r = −.08, p < 0.01).

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting behaviors | ||||||||

| 1. Positive parenting | — | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.01 | — | — | — |

| 2. Psychological control | −0.38 | — | 0.27*** | 0.14*** | 0.29*** | — | — | — |

| Adolescent adjustment | ||||||||

| 3. Conduct problems | −0.35 | 0.18 | — | 0.29*** | 0.31*** | — | — | — |

| 4. Emotional problems | −0.46* | 0.41 | 0.56** | — | 0.58*** | — | — | — |

| 5. Negative affect | −0.59** | 0.26 | 0.70** | 0.89*** | — | — | — | — |

| Baseline variables | ||||||||

| 6. Sex (1 = male) | 0.05 | 0.22 | −0.11 | 0.15 | 0.09 | — | — | — |

| 7. Age | −0.03 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.23 | — | — |

| 8. Ethnicity (1 = White) | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.25 | −0.01 | −0.40 | — |

| Mean/(Yes%) | 1.69 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.42 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 14.26 | 0.42 |

| SD | 1.26 | 0.32 | 0.23 | 0.47 | 0.73 | 0.49 | 1.74 | 0.49 |

| ICC | 0.43 | 0.27 | 0.48 | 0.62 | 0.47 | — | — | — |

| Range | 0–3 | 0–3 | 0–1.4 | 0–2 | 0–4 | 0–1 | 12–17 | 0–1 |

| Wave 1 ω (within/between) | (0.95/.96) | (0.95/.89) | (0.80/.92) | (0.83/.92) | (0.94/.96) | — | — | — |

| Wave 2 ω (within/between) | (0.98/.97) | (0.95/.90) | (0.86/.93) | (0.78/.91) | (0.90/.95) | — | — | — |

- Note: Within-person correlations are above the diagonal and between-person correlations are below the diagonal.

- Abbreviations: ICC = intra-class correlation coefficient, ω = Omega reliability.

- * p < 0.050

- ** p < 0.010

- *** p < 0.001.

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting behaviors | ||||||||

| 1. Positive parenting | — | −0.08** | −0.08** | −0.06* | −0.06* | — | — | — |

| 2. Psychological control | −0.22 | — | 0.20*** | 0.11*** | 0.25*** | — | — | — |

| Adolescent adjustment | ||||||||

| 3. Conduct problems | −0.36 | 0.73*** | — | 0.31*** | 0.25*** | — | — | — |

| 4. Emotional problems | −0.42* | 0.50* | 0.55*** | — | 0.26*** | — | — | — |

| 5. Negative affect | −0.08 | 0.28 | 0.41* | 0.56** | — | — | — | — |

| Baseline variables | ||||||||

| 6. Sex (1 = male) | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.43 | −0.30* | — | — | — |

| 7. Age | −0.14 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.05 | −0.08 | — | — |

| 8. Ethnicity (1 = White) | −0.21 | −0.35 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.10 | −0.47 | −0.10 | — |

| Mean/(Yes%) | 2.38 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 43.5 | 0.56 |

| SD | 0.97 | 0.20 | 035 | 0.31 | 0.53 | 0.42 | 6.05 | 0.50 |

| ICC | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.18 | 0.42 | — | — | — |

| Range | 0 – 3 | 0 – 2 | 0 – 2 | 0 – 2 | 0 – 4 | 0 – 1 | 34 – 60 | 0 – 1 |

| Wave 1 ω (within/between) | (0.96/.97) | (0.92/.87) | (0.72/.90) | (0.98/.99) | (0.95/.97) | — | — | — |

| Wave 2 ω (within/between) | (0.87/.86) | (0.94/.90) | (0.89/.90) | (0.92/.94) | (0.83/.81) | — | — | — |

- Note: Within-person correlations are above the diagonal and between-person correlations are below the diagonal. ICC = intra-class correlation coefficient, ω = omega reliability.

- * p < 0.050

- ** p < 0.010

- *** p < 0.001.

At the between-person level, positive parenting was negatively correlated with adolescent emotional problems for both parent- (r = −0.42, p < 0.05) and adolescent-reports (r = −0.46, p < 0.05), and negatively correlated with adolescent negative affect for adolescent-reports only (r = −0.59, p < 0.01). Psychological control was positively correlated with adolescent conduct problems (r = 0.73, p < 0.001) and emotional problems (r = 0.50, p < 0.05) in parent-reports only. Intra-class correlations (ICCs) suggested that 38%–82% of the variances of the reported key variables were due to within-person variations.

3.2 Changes in Parenting Behaviors and Adolescent Adjustment

Paired t-tests compared person average scores across waves for daily parenting behaviors and adolescent adjustment (Table 3). In adolescent-reports, there was a significant decrease in positive parenting across waves (1.88 ± 0.95 vs. 1.44 ± 0.93), t(29) = 3.00, p = 0.01. Changes in psychological control and all adolescent outcomes were not significant. In parent-reports, there was a significant decrease in conduct problems (0.31 ± 0.26 vs. 0.12 ± 0.20), t(29) = 4.19, p = 0.001, and increase in emotional problems (0.12 ± 0.12 vs. 0.20 ± 0.20), t(29) = −2.40, p = 0.02, across waves. Changes in parenting behaviors and negative affect were not significant. Therefore, H1 was partially supported.

| Variable | Adolescent-reports | Parent-reports | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-pandemic | During-pandemic | Pre-pandemic | During-pandemic | |||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | p | M | SD | M | SD | p | |

| Parenting behaviors | ||||||||||

| 1. Positive parenting | 1.88 | 0.95 | 1.44 | 0.93 | 0.01** | 2.24 | 0.56 | 2.38 | 0.64 | 0.28 |

| 2. Psychological control | 0.26 | 0.43 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.57 |

| Adolescent adjustment | ||||||||||

| 3. Conduct problems | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.001*** |

| 4. Emotional problems | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.02* |

| 5. Negative affect | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.12 |

- Note: Paired t-test comparing the daily averages of parent- and adolescent-reported core variables before and during the pandemic.

- * p < 0.025

- ** p < 0.005

- *** p < 0.001.

3.3 Changes in the Associations Between Daily Parenting Behaviors and Adolescent Adjustment

For both parent- and adolescent-reports, standardized within-person results (Tables 4 and 5) showed significant autoregressive paths for all outcome variables (Φs = 0.16 − 0.31, 95% CI = [0.09, 0.30] – [0.22, 0.45]). For adolescent-reports (Table 4), at the within-person level, positive parenting was negatively linked to negative affect (β = −0.06, 95% CI [−0.11, −0.01]) on the same day. The negative links between positive parenting and conduct problems (β = −0.05, 95% CI [−0.11, 0.01]), and with emotional problems (β = −0.03, 95% CI [−0.09, 0.02]) were not significant. Psychological control was positively linked to conduct problems (β = 0.17, 95% CI [.12, 0.21]), emotional problems (β = 0.08, 95% CI [0.03, 0.14]), and negative affect (β = 0.14, 95% CI [0.09, 0.19]) on the same day. Therefore, H2 was supported. Parent-reports showed mostly consistent results (Table 5). Specifically, at the within-person level, positive parenting was negatively linked to conduct problems (β = −0.09, 95% CI [−0.15, −0.04]), emotional problems (β = −0.07, 95% CI [−0.12, −0.02]), and negative affect (β = −0.12, 95% CI [−0.11, −0.02]) on the same day, whereas psychological control was positively linked to conduct problems (β = 0.21, 95% CI [0.17, 0.25]), emotional problems (β = 0.12, 95% CI [0.07, 0.17]), and negative affect (β = 0.18, 95% CI [0.14, 0.23]) on the same day. All estimated random slope effects for both parent- and adolescent-reports were significant, indicating the presence of substantial between-person differences in these effects (Tables 4 and 5, σ̂2s = 0.001–1.138). There were significant weekend effects for adolescent-reported emotional problems (β = −0.09) and negative affect (β = −0.07), suggesting that adolescents experienced lower levels of emotional problems and negative affect during weekend than weekdays.

| Conduct problem | Emotional problem | Negative affect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CI | β | B | 95% CI | β | B | 95% CI | β | |

| Positive parenting (PP) | |||||||||

| Within-person level: regression coefficients (i.e., fixed effects) | |||||||||

| PP | −0.01 | [−0.03, −0.01] | −0.05 | −0.01 | [−0.03, 0.01] | −0.03 | −0.03 | [−0.07, 0.01] | −0.06* |

| COVID (1 = Yes) | −0.03* | [−0.06, −0.01] | −0.10* | −0.02 | [−0.10, 0.05] | −0.01 | −0.07 | [−0.17, 0.03] | −0.05 |

| Autoregression | 0.19* | [0.04, 0.31] | 0.18* | 0.27* | [0.16, 0.36] | 0.26* | 0.35* | [0.23, 0.45] | 0.31* |

| Linear trend | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.01] | 0.01 | −0.01* | [−0.01, 0.01] | −0.06* | −0.01 | [−0.01, 0.01] | −0.02 |

| Weekend effects | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.03] | 0.03 | −0.05* | [−0.08, −0.02] | −0.10* | −0.05 | [−0.10, 0.01] | −0.04 |

| Between-person level: variance components (i.e., random effects) | |||||||||

| Intercept | −0.22 | [−0.68, 0.21] | — | −0.64 | [−1.57, 0.27] | — | −0.39 | [−1.57, 0.75] | — |

| PP | 0.001 | [0.001, 0.002] | — | 0.002 | [0.001, 0.004] | — | 0.002 | [0.001, 0.008] | — |

| COVID | 0.003 | [0.001, 0.009] | — | 0.025 | [0.008, 0.068] | — | 0.049 | [0.018, 0.125] | — |

| Autoregression | 0.073 | [0.031, 0.159] | — | 0.040 | [0.010, 0.098] | — | 0.046 | [0.016, 0.112] | — |

| Psychological control (PC) | |||||||||

| Within-person level: regression coefficients (i.e., fixed effects) | |||||||||

| PC | 0.20* | [0.007, 0.33] | 0.17* | 0.12* | [0.02, 0.24] | 0.08* | 0.41* | [0.21, 0.64] | 0.14* |

| COVID (1 = Yes) | −0.03 | [−0.08, 0.02] | −0.06* | −0.02 | [−0.12, 0.07] | −0.02 | −0.04 | [−0.14, 0.06] | −0.02 |

| Autoregression | 022* | [0.09, 0.33] | 0.17* | 0.21* | [0.08, 0.32] | 0.18* | 0.34* | [0.21, 0.44] | 0.29* |

| Linear trend | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.01] | 0.01 | −0.01* | [−0.01, 0.01] | −0.07* | −0.01 | [−0.01, 0.01] | −0.03 |

| Weekend effects | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.04] | 0.05 | −0.05* | [−0.09, −0.02] | −0.09* | −0.08* | [−0.15, −0.02] | −0.07* |

| Between-person level: Variance components (i.e., random effects) | |||||||||

| Intercept | −0.29 | [−0.75, 0.12] | — | −1.17 | [−2.08, −0.25] | — | −0.46 | [−1.64, 0.63] | — |

| PC | 0.061 | [0.017, 0.175] | — | 0.020 | [0.002, 0.080] | — | 0.092 | [0.013, 0.356] | — |

| COVID | 0.008 | [0.002, 0.021] | — | 0.046 | [0.020, 0.102] | — | 0.026 | [0.002, 0.083] | — |

| Autoregression | 0.048 | [0.017, 0.121] | — | 0.053 | [0.015, 0.140] | — | 0.045 | [0.014, 0.117] | — |

- Note: p = Bayesian equivalent to one-side p values, 95% CI = 95% credible interval of unstandardized estimates. Linear trend and weekend effects were controlled for potential linear increase/decrease as well as weekend versus weekday effects on adolescent outcomes, respectively. Autoregressive effects represent the effect of the adolescent outcomes of the previous day (t − 1) on itself today (t). Demographic variables (age, sex, ethnicity-race) were controlled (omitted from the table) for between-person level random intercept, hence creating negative estimates.

- * p < 0.025

- ** p < 0.005

- *** p < 0.001.

| Conduct problem | Emotional problem | Negative affect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CI | β | B | 95% CI | β | B | 95% CI | β | |

| Positive parenting (PP) | |||||||||

| Within-person Level: regression coefficients (i.e., fixed effects) | |||||||||

| PP | −0.03** | [−0.05, −0.01] | −0.09** | −0.02* | [-0.05, −0.00] | −0.07** | −0.03 | [−0.06, 0.00] | −0.12** |

| COVID (1 = Yes) | −0.14** | [−0.20, −0.07] | −0.22*** | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.08] | 0.02 | 0.04 | [−0.03, 0.11] | 0.04 |

| Autoregression | 0.09 | [−0.04, 0.21] | 0.09*** | 0.16** | [0.03, 0.28] | 0.12*** | 0.16** | [0.06, 0.25] | 0.31*** |

| Linear trend | 0.01** | [0.01, 0.01] | 0.07** | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.01] | 0.01 | −0.01 | [−0.01, 0.01] | −0.02 |

| Between-person level: variance components (i.e., random effects) | |||||||||

| Intercept | 0.22 | [−0.64, 1.10] | — | −0.03 | [−0.47, 0.39] | — | 0.54 | [−0.46, 1.45] | — |

| PP | 0.001 | [0.001, 0.003] | — | 0.001 | [0.000, 0.002] | — | 0.002 | [0.001, 0.005] | — |

| COVID | 0.021 | [0.009, 0.044] | — | 0.014 | [0.005, 0.036] | — | 0.020 | [0.005, 0.053] | — |

| Autoregression | 0.059 | [0.008, 0.140] | — | 0.058 | [0.020, 0.140] | — | 0.035 | [0.013, 0.085] | — |

| Psychological control (PC) | |||||||||

| Within-person level: regression coefficients (i.e., fixed effects) | |||||||||

| PC | 0.73** | [0.30, 1.15] | 0.21*** | 0.31** | [0.11, 0.51] | 0.12*** | 0.72** | [0.29, 1.11] | 0.18*** |

| COVID (1 = Yes) | −0.15*** | [−0.20, −0.09] | −0.21*** | 0.03 | [−0.02, 0.09] | 0.04 | 0.04 | [-0.02, 0.10] | 0.03 |

| Autoregression | 0.16** | [0.07, 0.25] | 0.12*** | 0.18** | [0.06, 0.28] | 0.13*** | 0.16** | [0.07, 0.25] | 0.13*** |

| Linear trend | 0.01** | [0.01, 0.01] | 0.06** | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.01] | 0.03 | −0.01 | [−0.01, 0.01] | −0.01 |

| Between-person level: variance components (i.e., random effects) | |||||||||

| Intercept | −0.07 | [−0.47, 0.34] | — | −0.17 | [−0.42, 0.07] | — | 0.20 | [−0.41, 0.79] | — |

| PC | 1.138 | [0.565, 2.378] | — | 0.146 | [0.054, 0.384] | — | 0.848 | [0.435, 1.809] | — |

| COVID | 0.012 | [0.005, 0.027] | — | 0.011 | [0.004, 0.028] | — | 0.013 | [0.002, 0.041] | — |

| Autoregression | 0.021 | [0.007, 0.058] | — | 0.047 | [0.019, 0.109] | — | 0.022 | [0.007, 0.062] | — |

- Note: p = Bayesian equivalent to one-side p values, 95% CI = 95% credible interval of unstandardized estimates. Linear trend was controlled for potential linear increase/decrease in adolescent outcomes. Autoregressive effects represent the effect of the adolescent outcomes of the previous day (t − 1) on itself today (t). Demographic variable (age, sex, ethnicity-race) were controlled (omitted from the table) for between-person level random intercept, hence creating negative estimates.

- * p < 0.025

- ** p < 0.005

- *** p < 0.001.

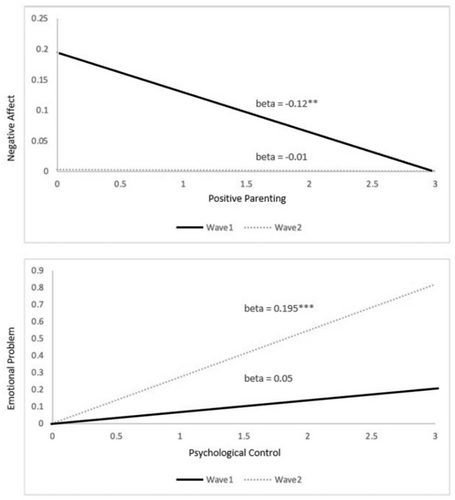

Notably, based on adolescent-reports (Table 6), there was a significant interaction involving the onset of COVID-19 pandemic with daily positive parenting on negative affect (β = 0.13, 95% CI [0.02, 0.23]), and with daily psychological control on emotional problems (β = 0.07, 95% CI [0.01, 0.13]). Simple slopes were plotted to illustrate the within-day associations between positive parenting and negative affect in each wave (Figure 1 top), and between psychological control and emotional problems in each wave (Figure 1 bottom). Specifically, from wave 1 to wave 2, the negative association between positive parenting and negative affect was weakened and became nonsignificant (−0.12, p < 0.01 vs. −0.01, ns), whereas the positive association between psychological control and emotional problems was exacerbated (0.05, ns vs. 0.195, p < 0.001). Therefore, H3 was supported. No significant interactions in parent-reports were revealed, which supported H4.

| Conduct problem | Emotional problem | Negative affect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CI | β | B | 95% CI | β | B | 95% CI | β | |

| Positive parenting (PP) | |||||||||

| Within-person level: Regression coefficients (i.e., fixed effects) | |||||||||

| PP | −0.02* | [−0.04, −0.01] | −0.11** | −0.02 | [−0.05, 0.01] | −0.07 | −0.07** | [−0.11, −0.02] | −0.12** |

| COVID (1 = Yes) | −0.05*** | [−0.21, −0.11] | −0.16*** | −0.06*** | [−0.09, 0.02] | 0.17 | −0.18** | [−0.32, −0.04] | −0.16** |

| PP×COVID | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.04] | 0.11 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.06] | 0.09 | 0.07* | [0.01, 0.12] | 0.13* |

| Autoregression | 0.18** | [0.04, 0.30] | 0.18*** | 0.26*** | [0.16, 0.36] | 0.25*** | 0.35*** | [0.22, 0.45] | 0.31*** |

| Linear trend | 0.01 | [−0.01, −0.01] | −0.01 | −0.01** | [−0.01, −0.01] | −0.07** | −0.01 | [−0.01, 0.01] | −0.02 |

| Weekend effect | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.03] | 0.03 | −0.05*** | [−0.08, −0.02] | 0.10*** | −0.05 | [−0.11, 0.01] | −0.05 |

| Between-person level: variance components (i.e., random effects) | |||||||||

| Intercept | 0.13 | [0.08, 0.18] | — | 0.35 | [0.24, 0.47] | — | 0.50 | [0.36, 0.66] | — |

| PP | 0.001 | [0.001, 0.002] | — | 0.002 | [0.001, 0.004] | — | 0.002 | [0.001, 0.007] | — |

| COVID | 0.003 | [0.001, 0.010] | — | 0.027 | [0.010, 0.067] | — | 0.048 | [.015, 0.125] | — |

| PP×COVID | 0.001 | [0.001, 0.002] | — | 0.001 | [0.001, 0.003] | — | 0.002 | [0.001, 0.007] | — |

| Autoregression | 0.072 | [0.034, 0.169] | — | 0040 | [0.015, 0.099] | — | 0.048 | [0.020, 0.115] | — |

| Psychological Control (PC) | |||||||||

| Within-person level: regression coefficients (i.e., fixed effects) | |||||||||

| PC | 0.13* | [0.02, 0.27] | 0.11*** | 0.07 | [−0.05, 0.22] | 0.05 | 036** | [−0.65, −0.13] | 0.12*** |

| COVID (1 = Yes) | −0.05* | [−0.10, −0.01] | −0.10** | −0.06 | [−0.15, 0.02] | −0.07 | −0.07 | [−0.17, 0.03] | −0.05 |

| PC×COVID | 0.16 | [−0.19, 0.47] | 0.08 | 0.21 | [−0.09, 0.53] | 0.07* | 0.15 | [0.13, 0.68] | 0.04 |

| Autoregression | 0.21** | [0.09, 0.30] | 0.16*** | 0.21 | [−0.15, 0.02] | 0.18*** | 0.33*** | [0.21, 0.44] | 0.28*** |

| Linear trend | 0.01 | [−0.01, −0.01] | 0.02 | −0.01* | [−0.01, −0.01] | −0.06* | −0.01 | [−0.01, 0.01] | −0.03 |

| Weekend effect | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.04] | 0.05 | −0.05** | [−0.09, −0.02] | −0.09** | −0.08* | [−0.15, −0.02] | −0.07* |

| Between-person level: variance components (i.e., random effects) | |||||||||

| Intercept | 0.08 | [0.03, 0.13] | — | 0.36 | [0.25, 0.49] | — | 0.39 | [0.25, 0.54] | — |

| PC | 0.038 | [0.010, 0.152] | — | 0.024 | [0.003, 0.092] | — | 0.115 | [0.023, 0.396] | — |

| COVID | 0.009 | [0.003, 0.022] | — | 0.035 | [0.015, 0.078] | — | 0.017 | [0.002, 0.067] | — |

| PC×COVID | 0.318 | [0.111, 0.887] | — | 0.178 | [0.044, 0.597] | — | 0.853 | [0.188, 2.867] | — |

| Autoregression | 0.052 | [0.023, 0.123] | — | 0.057 | [0.019, 0.137] | — | 0.048 | [0.020, 0.112] | — |

- Note: p = Bayesian equivalent to one-side p values, 95% CI = 95% credible interval of unstandardized estimates. Linear trend and weekend effect controlled for potential linear increase/decrease as well as weekend versus weekday effects on adolescent outcomes, respectively. Autoregressive effects represent the effect of the adolescent outcomes of the previous day (t − 1) on itself today (t). Significant interactions involving COVID were bolded.

- * p < 0.025

- ** p < 0.005

- *** p < 0.001.

4 Discussion

Parenting behaviors play a prominent role in adolescent development and are crucial assets in supporting adolescents navigate through this important developmental period (Smetana and Rote 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic brought numerous changes and challenges to the family well-being and parent–adolescent relationships (Prime et al. 2020). Leveraging a two-wave multi-informant month-long daily diary design, this study examined the changes in daily parenting and adolescent maladjustment, as well as their within-day associations before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings generally support the risk processes within the COVID-19 family disruption framework (Prime et al. 2020) in undermining daily caregiver/family functioning and adolescent well-being. Generally in line with our hypotheses, adolescents reported decreased positive parenting behaviors, while parents reported decreased adolescent conduct problems and increased adolescent emotional problems from before to during the pandemic. Positive parenting was negatively linked with adolescent negative affect on the same day, whereas psychological control was positively linked with adolescent conduct problems, emotional problems, and negative affect on the same day based on both parent- and adolescent-reports. In addition, current results confirmed the moderating effect of the pandemic based on adolescent-reports, such that the protective effect of positive parenting on negative affect was suppressed, and the adverse effect of psychological control on emotional problems was amplified.

4.1 Changes in Parenting and Adolescent Maladjustment From Before to During the Pandemic

Changes in parenting and adolescent maladjustment from before to during the pandemic were partly consistent with our expectations in H1. Particularly, we found adolescent-reported declines in positive parenting and parent-reported increases in emotional problems, suggesting disrupted parenting and child functioning. From the family disruption perspective, these changes may be the consequences of initial caregiver vulnerabilities (e.g., parenting stress), which limit parenting resources and quickly spiral down to disruptions in the whole-family (Prime et al. 2020). The decrease in conduct problems during the pandemic might be explained by the restricted social activities and contact opportunities due to the lockdown policies. Comparing to the widely reported increase in internalizing symptoms, there is relatively limited research addressing changes in externalizing problems, and available studies provide mixed or insignificant findings (Roche et al. 2022; Shoychet et al. 2023). Consistent with the pandemic literature, the current findings support the documented increase in internalizing symptoms. It should be noted that previous longitudinal studies have documented age-related changes in parent–child relationships and adolescent maladaptation, such as the decrease in parental warmth (Shanahan et al. 2007) and the increase in internalizing symptoms (Papachristou and Flouri 2020) from early to middle adolescence. Therefore, the decrease in positive parenting, the increase in adolescent emotional problems, as well as the changes in their daily links observed in the current study could also be due to normative age-related changes in the current sample from middle to late adolescence regardless of the pandemic influence, which nonetheless could not be statistically distinguished.

Not all changes in parenting behaviors and adolescent maladjustment were significant, which was not surprising. For instance, although pertinent theories suggest a potential increase in maladaptive parenting behaviors (Brown et al. 2020; Prime et al. 2020), direct supporting evidence for the change in parental psychological control is lacking (Campione-Barr et al. 2024). Notably, one study expecting deteriorated parenting during the pandemic lockdown instead found decreased adolescent perceptions of psychological control and overcontrol (Bacikova-Sleskova et al. 2021). Likewise, Janssen et al. 2020 did not find the expected changes in adolescent-reported daily positive or negative affect from before to during the pandemic. Nonetheless, the lack of significant findings could also reflect the complex nature and sometimes incongruent perceptions of social experiences by parents and adolescents during the pandemic (Janssens et al. 2021). Therefore, future family-based research should also incorporate multi-informant assessments to understand patterns of convergence and divergence from multiple family members' perspectives (Li and Zheng 2025).

4.2 Associations Between Daily Parenting and Adolescent Maladjustment

In line with our hypotheses in H2, positive parenting was negatively linked to same-day adolescent negative affect, whereas psychological control was positively linked to same-day adolescent conduct problems, emotional problems, and negative affect, for both parent- and adolescent-reports. On the one hand, positive parenting behaviors characterized by parental warmth and affection are assets that protect against adverse developmental outcomes (Pinquart 2017; Prime et al. 2020). These effects were widely found in pre-pandemic cross-sectional and longitudinal research (Shoychet et al. 2023), in some intensive longitudinal research during the pandemic (Leijten et al. 2024; Neubauer et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2021; 2022), and were also corroborated in the current study. On the other hand, controlling parenting behaviors clash with the developmental need for independence and autonomy during adolescence and thus pose risks for maladjustment in everyday life (Pinquart 2017; Xu and Zheng 2022). Although changes in the effects of psychological control during the pandemic were unclear given the scarce research evidence, the current finding supports the pre-pandemic literature and suggests that psychological control remains as a risk factor during the pandemic. Moreover, congruent patterns were observed based on reports from both parents and adolescents, adding on to the robustness of the current findings, and confirming the salient yet opposite effects of the two parenting dimensions on daily adolescent maladjustment.

Notably, based on adolescent-reports, the onset of the pandemic suppressed the negative daily association between positive parenting and adolescent negative affect, supporting H3. Shifts in social routines, activities, and daily experiences during the extended lockdown period challenged and disrupted parent–adolescent relationships and interactions (Donker et al. 2021). Over time, pandemic disruptions may have outweighed the protective influences of positive parenting behaviors on adolescent development. For instance, parental support did not mitigate the impact of various pandemic stressors on adolescent internalizing symptoms in a two-wave study before and after the onset of COVID-19 (Roche et al. 2022). Consistent with these observations, the current finding points to a diminished beneficial role of positive parenting behaviors during the pandemic, possibly due to the heightened stress and burden of childcare and other parental responsibilities (Roche et al. 2022). On the other hand, the pandemic amplified the positive daily association between psychological control and adolescent emotional problems. As expected, the lockdown may amplify pre-existing negative family dynamics, further worsening the situations in high-risk families that were already struggling with maladaptive relationships (Campione-Barr et al. 2024). Consistent with current findings, in a three-wave study since the onset of COVID-19, parental warmth was not related to children's maladjustment during the pandemic, whereas harsh discipline increased during the pandemic and was related to subsequent increase in children's internalizing and externalizing problems (Fosco et al. 2022).

It should be noted that not all reported changes in parenting and adolescent maladjustment across waves were present or consistent for parent- and adolescent-reports, in line with H4. The congruency and discrepancy between adolescent- and parent-reports are expected and widely evident in the existing literature (De Los Reyes and Ohannessian 2016; Hou et al. 2020), including research on daily parenting and adolescent emotional problem (Li and Zheng 2025; Xu and Zheng 2022). When measuring changes after the onset of pandemic, both parents and adolescents have reported positive, negative, as well as mundane experiences, reflecting the two-sided and sometimes contradictory perceptions of social interactions within the same family during this time (Campione-Barr et al. 2024). Although parents and adolescents did not appear to be as disrupted as we expected based on current findings, cautions are needed as the more detrimental effects of the pandemic may emerge much later after the onset (Fosco et al. 2022). Lastly, the interaction effects were only evident in adolescent-reports, possibly suggesting more accurate and informative self-perceptions than observations from others. Therefore, in the case of limited research resources, researchers should pay more attention to adolescents' own perceptions of their well-being. Methodologically, this pattern may also have emerged partly due to shared methods variance, such that those adolescents with elevated maladjustment may tend to perceive their parent–adolescent relationships more negatively.

Collectively, the current findings demonstrate the potent impact of daily parenting behaviors on adolescent daily maladjustment, which are situated in changing macro historical-societal contexts. Regardless of the pandemic, parents are important socialization agents that provide guidance and support for children to successfully navigate through the adolescence period. Although the pandemic has passed in some way, many of its repercussions remain, and similar societal disruptions or major historical events might occur in the future, which could jeopardize adaptive parent–child dynamics in a comparable way. It is of paramount importance to understand how the pandemic may have interfered with family dynamics to provide malleable targets for future intervention that aims at promoting a return from environmental disruption to family well-beings. In this way, current findings carry crucial implications for future research and intervention on the importance of fostering and promoting adaptive parent–child relationships and nurturing positive parenting behaviors in daily life when facing similar future events and experiences. Specifically, the current study emphasizes that a holistic intervention approach should focus on the interactive dynamics across parent–adolescent dyads instead of parents alone, as the environmental disruption could also contaminate the influences of parenting behaviors.

4.3 Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

Intensive longitudinal data provided us with more fine-grained insights into the fluctuations of parenting and adolescent behaviors as well as their dynamic links on a micro timescale (Zheng and Goulter 2024). The measurement burst design across two time-points as adopted in the current study—before and during the COVID-19 pandemic—allowed us to detect long-term changes in short-term parent–adolescent dynamics under the influence of the pandemic. In addition, the multi-informant approach including both parent- and adolescent-reports offered a more comprehensive picture in discovering the congruency and discrepancy between parents' and adolescents' perceptions. The month-long daily diary design at each timepoint also provides large number of daily observations to draw conclusions regarding within-person daily processes. To our best knowledge, the current study represents among the first efforts to investigate changes in the daily associations between parenting and adolescent maladjustment from before to during the pandemic, especially with a multi-informant approach.

Several limitations should be noted when interpreting the current findings. First, our sample of only 30 parent–adolescent dyads was small, which could have insufficient statistical power to detect between-level associations. Therefore, we primarily focused on interpreting within-person associations results based on hundreds of daily observations. With over 1400 daily observations at the within-person level, statistical simulations showed that we have over 0.95 power to detect interaction effects of the effect sizes revealed in our findings. Second, our sample consisted largely of White and Asian participants, which is representative of the Canadian population composition. At the same time, other ethnic-racial minority families such as Black and Latinx were underrepresented, limiting the generalizability of the current findings to more diverse Canadian families. Third, the current community sample was comprised of families with relatively higher socioeconomic status considering parental education level and family income. Future studies on families living under less fortunate circumstances or using clinical adolescent samples may add more nuances to and extend the current findings. Relatedly, initial parental vulnerabilities before the pandemic (e.g., parenting stress) could be related to changes in daily parenting during the pandemic. Future studies with sufficiently large sample size could consider such vulnerability factors as potential moderators to examine cross-level interactions. It should also be noted that we only controlled for demographic variables but did not control for other between-person variables such as parenting measures from the baseline, given their low correlations with main outcome variables and the limited person-level sample size. Taking into account of between-person variables, such as the dispositional (i.e., person-average) level of parenting, could offer valuable additional information in understanding within-person parent–adolescent dynamics. Future studies with sufficient sample size at the between-person level should also examine between-person differences in the baseline and explore the long-term changes in the levels of parenting and adolescent maladjustment.

Fourth, given the long temporal gap between the two waves, the observed changes from before to during the pandemic could be the joint effect of the pandemic influence and normative development of adolescents, which unfortunately could not be disentangled by the current design. Future studies that focus on the long-term influence of societal disruptions should include longitudinal control groups without such historical experiences to separate the historical-contextual-environmental influence from normative developmental changes. Fifth, it is important to note that we could not draw conclusions about the directions of effects. Adolescents' daily maladjustment could potentially influence parenting behaviors as well, as revealed in some previous daily parenting studies (Li and Zheng 2025; Xu and Zheng 2022; Keijsers et al. 2010). Sixth, it should be noted that positive parenting in the current study primarily measured the praise and compliment aspects of parenting behaviors with only three binary response questions, which could be limited in capturing the range of positive parenting behaviors. Future studies should also consider other positive parenting dimensions, such as warmth and involvement. Seventh, we have no direct information regarding how each family was affected by the pandemic (e.g., financial issues, unemployment, health), which information could have expanded our understanding about the pandemic influence on our sample and lent a supportive hand to our interpretation of the findings. Researchers with relevant measures available can take advantage of them in future studies to further explore the mechanism of how societal disruption could exert influence on each family. Lastly, it is possible that disruptions to parenting and adolescent adjustment would be more evident on a different (e.g., longer) timescale than was measured in this study with only one wave of measurement during the pandemic. Future measurement burst designs with longer study duration and more measurement waves/bursts can be helpful in determining the stability and long-term trajectories of short-term dynamics.

4.4 Implications

Family-based interventions aiming at bolstering family cohesion, promoting the use of positive parenting behaviors, and minimizing the use of controlling parenting behaviors may offer helpful resources for parents who may otherwise resort to maladaptive parenting behaviors when coping with the added stressors and responsibilities. In addition, specific skills and strategies should be provided to parents such that they can provide more stable and consistent levels of parenting behaviors to their children (e.g., avoid controlling behaviors), especially during times of elevated stress and uncertainties. Similarly, interventions should target adolescents' own interpretations of family dynamics, response patterns to parenting behaviors, as well as the skills to interact with their parents, which could not only promote their short-term adjustment in daily life, but also help them build cohesive relationships with their parents that provide long-lasting benefits into the adulthood. Lastly, the congruency and discrepancy between parents' and adolescents' perceptions of parenting and their daily adjustment can yield valuable information that promotes the well-being of adolescents and all family members.

5 Conclusions

This study highlights changes in daily parent–adolescent dynamics under the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic through a novel two-wave multi-informant month-long daily diary design. Effective parenting plays a prominent role in supporting daily adolescent adjustment and well-being, but some of its effects are disrupted by the pandemic. The findings are in line with the COVID-19 family disruption framework, where initial pandemic-related disruptions in caregiver functioning gradually infiltrates the whole-family system, leading to maladaptive parenting and deteriorated parent–child relationships, which ultimately undermines normative child functioning. Lastly, including multiple informants' perspectives could be a valuable addition to the emerging intensive longitudinal studies in relevant developmental research areas.

Acknowledgments

This research study was supported partly with funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (IDG 430-2018-00317 and 409-2020-00080) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (RGPIN-2020-04458 and DGECR-2020-00077) of Canada, and a Killam Research Fund Cornerstone Grant.

Ethics Statement

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent

All interested participants who reached out to the research team provided consent/assent online.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethics restriction and confidentiality considerations, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.