Maternal childhood adversity and adolescent marijuana use at age 17 years: The role of parental mental health and parenting behaviors

Abstract

Introduction

Children's risk for marijuana use may be linked to their parents' history of childhood adversity, yet little is known about the mechanisms underlying this link. This study examined whether maternal parenting behavior and mental health serve as mechanisms linking maternal childhood adversity to their children's marijuana use at age 17 years, by gender.

Methods

Data were from the Young Women and Child Development Study (59% male), a longitudinal panel study, which began in 1988 and followed mother–child dyads for 17 years (n = 240). Participants were recruited from health and social services agencies located in a metropolitan region of Washington State. Hypotheses were tested using Structural Equation Modeling in Mplus. Multiple-group analysis was conducted to evaluate potential gender differences.

Results

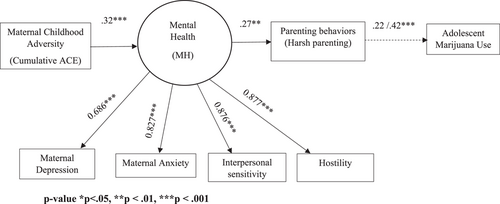

Results showed that maternal childhood adversity was associated with their mental health outcomes (β = .32, p < .001), which in turn was predictive of mothers' harsh parenting (β = .27, p < .01). Maternal harsh parenting behavior was then associated with their children's marijuana use at age 17 years (β = .34, p < .001). Multiple group analyses revealed that the path from harsh parenting to adolescent marijuana use differed across genders being only significant for boys (β = .42, p < .001).

Conclusions

The intergenerational impact of childhood adversity highlights the need for interventions that target both parents and children. This would support teen mothers with a history of childhood adversity to acquire skills and knowledge to help mitigate its impact on their parenting behaviors and offset risks for their children.

1 INTRODUCTION

Marijuana is one of the most frequently used illicit substances among adolescents (Johnston et al., 2016). The 2019 findings from the National Institute on Drug Abuse revealed that 14% of high school seniors in the United States had used marijuana in the past month and 22% currently used marijuana (Lipari, 2019). Individuals who begin using marijuana before the age of 18 years are four to seven times more likely to develop a marijuana use disorder than those who start using it later in life (Richter et al., 2017). Additionally, adolescent marijuana use may increase vulnerability to addiction to other classes of drugs and psychiatric disorders later in life (Rogers et al., 2021).

In 2020, close to 5% of births in the United States were to teen mothers (~157,000; Osterman et al., 2022). Although teen births have significantly declined since the 1990s, the teen birth rate in the United States remains the highest among developed countries (The World Bank, 2022). Further, there remain continued disparities by race and ethnicity with Hispanic, Native American, and non-Hispanic Black teens more than two times more likely to give birth as a teen than their non-Hispanic White counterparts (Martin et al., 2021). Children born to teen mothers are often at increased risk for behavioral health problems (Huang et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2020), including substance use (Cederbaum et al., 2020), and compromised development (Lee et al., 2020). Previous studies suggest that being born to a teen mother increases the risk of marijuana use (De Genna et al., 2015) and marijuana abuse or dependence (McGrath et al., 2014). These studies highlight the need to focus on the possible increased risk for substance-use behaviors among children of teen mothers.

Although multiple risk factors for adolescent substance use have been established (Oztas et al., 2018), including the influence of parental marijuana use on offspring's marijuana use behaviors (Cederbaum et al., 2021), research on the antecedents of adolescent substance use has rarely assessed the mother's own adverse experience (Stargel & Easterbrooks, 2020), especially among children of teen mothers. Having a mother with childhood adversity experiences may increase the likelihood that offspring experience adverse outcomes, such as mental health problems and marijuana use (Ruybal & Crano, 2020). Childhood adversity also plays a critical role in shaping risks for health outcomes across the lifespan (Racine et al., 2021). Although higher numbers of adversity exposures are associated with behavioral health problems in childhood and adulthood (McDonnell & Valentino, 2016; Stepleton et al., 2018), there is little published evidence regarding intergenerational associations between childhood adversity in parents and behavioral health outcomes in their children (Schickedanz et al., 2018).

Examining the intergenerational impact of childhood adversity among teen mothers and their children may be particularly important given the increased likelihood of teen mothers (as compared with older mothers) experiencing significant adversity exposures during childhood (Freed & SmithBattle, 2016; Madigan et al., 2014), and additional adversity experiences after childbirth (Okine et al., 2020; Stargel & Easterbrooks, 2020). Further, emerging evidence suggests that children's risk for compromised behavioral health may be linked to the parent's history of childhood adversity (Cooke et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2022). To better understand the intergenerational impact of maternal adversity on children's marijuana use behaviors, this study examines maternal mental health and parenting behaviors as mechanisms linking maternal childhood adversity to their children's marijuana use at age 17 years. Additionally, gender differences were examined to inform the future development of tailored prevention and intervention programs that address adolescent marijuana use.

1.1 Childhood adversity, maternal mental health, and parenting

Emerging evidence has shown that severe stress in early childhood produces a series of events that may alter brain development, increasing the risk of poor health and mental well-being in adulthood (Chan et al., 2021; Franz et al., 2019). Experiencing adversity in childhood and postpartum can affect maternal psychological functioning and quality of life, both before and after the birth of their child (Pasalich et al., 2016). Teen mothers with childhood adversity may experience a higher risk of adverse mental health outcomes, including depression (Kamalak et al., 2021), posttraumatic stress disorder (Madigan et al., 2015), and parental affective symptoms (e.g., distress and anxiety; Myhre et al., 2014). The Family Stress Model (Masarik & Conger, 2017) provides a working understanding of the impact of maternal mental health on children's behaviors. In the model, external stressors (like childhood adversities) are noted as influencing maternal mental health, which in turn influences parenting behaviors. It is this disruption that impacts children's behaviors (Masarik & Conger, 2017). As such, parenting may be the risk factor that is the most proximal to children, linking maternal adversity to their children's behavioral outcomes (Yoon et al., 2019). Previous studies examining the underlying mechanisms between maternal childhood adversity experiences and child behavioral outcomes found support for an indirect pathway, in which mothers' symptoms of anxiety and depression predicted their children's behavioral outcomes at age 3 years (Cooke et al., 2019). These studies suggested that mental health outcomes stemming from childhood adversity may operate as distal risk factors for negative outcomes in their offspring by impacting the quality of the parent-child relationship at age 4.5 years (Pasalich et al., 2016). However, most intergenerational studies have focused on earlier developmental periods. Going beyond early childhood is important as pubertal maturation has been associated with elevated responsiveness to stress (Copeland et al., 2019; Dahl & Gunnar, 2009). This consideration suggests that the impacts of maternal childhood adversity on children's behavioral health may emerge more prominently during adolescence (Copeland et al., 2019).

Parents with a history of childhood adversity may demonstrate hostile parenting (e.g., critical, and abrasive behavior toward child) and cognitive biases toward aggressive responses in relationships (Berlin et al., 2011). Moreover, childhood adversity may disrupt the acquisition of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral capacities that are essential for healthy and nurturing parenting (Stepleton et al., 2018). Parent's report of depressive symptoms has also been found as a predictive factor for harsh parenting, with a parent's report of their depressive symptoms predicting their over-reactivity in disciplinary encounters (Kelley et al., 2015). The stressful home environment, created as a result of harsh-parenting behavior (Brody et al., 2014), may negatively impact the quality of parent-adolescent relationships and further expose adolescents to behavioral health problems such as marijuana use (Kim-Spoon et al., 2014; Spear, 2015). Although the relationship between maternal adversity and harsh parenting, and the relationship between harsh parenting and youth's substance behavior, have been established separately (Kim-Spoon et al., 2014), no identified study has evaluated harsh parenting as a possible mechanism linking maternal childhood adversity to youth's marijuana use.

1.2 Gender variations in adolescent marijuana use behaviors

Previous studies have conceptually proposed and empirically examined gender variations in the influences of risk factors on behavioral health outcomes (McHugh et al., 2018). Conceptually, the gender socialization hypothesis (Kågesten et al., 2016) and gendered strain theory (Broidy & Agnew, 1997) suggest that response to distress tends to vary by gender and this often results in distinct pathways in behavioral health. Thus, in response to the distress, girls are more likely to internalize their feelings (Gutman & McMaster, 2020), whereas boys may manifest their distress in the form of externalizing behaviors, such as marijuana use (Hammerslag & Gulley, 2016). Further, during adolescence, gender norms become more recognized (Kågesten et al., 2016) and gendered behavior intensifies (Hill & Lynch, 1983), resulting in more distinct gendered patterns in behavioral health outcomes (Gutman & McMaster, 2020).

Using the lens of gender socialization (Carter, 2014) and gender strain (Broidy & Agnew, 1997) theories, the impact of harsh parenting may have varied impacts on marijuana use among boys and girls. For instance, previous studies found gender differences in the association between parenting behaviors (specifically harsh parenting) and marijuana use behaviors (Rusby et al., 2018), indicating that parenting behaviors might be a stronger predictor of marijuana use for boys. However, others have documented that parenting behaviors may have a greater influence on the marijuana use behaviors of girls (McHugh et al., 2018; Skeer et al., 2011), resulting in an inconsistent relationship between the impact of parenting behaviors and children's substance use by gender (Banks et al., 2017; Rusby et al., 2018). Given these inconsistencies, examining gender variations in marijuana use behaviors among children with mothers who have experienced adversity, can enhance the field's capacity to identify potential risk differences, and ultimately identify important prevention targets for this population.

1.3 Current study

The deleterious influences of maternal childhood adversity have been found to impact their children's behavioral health outcomes (Stargel & Easterbrooks, 2020); mechanisms underlying the impact of parental adversity on adolescent marijuana use remain understudied (Cooke et al., 2019). Further, few studies to date have expanded this work to experiences among teen mothers and their children (Yoon et al., 2019) and little empirical attention has been given to possible gender effects in the link between parenting harsh behavior (stemming from childhood adversity) and adolescent marijuana use, despite differences in the developmental and behavioral health outcomes across genders (Rusby et al., 2018). This study leverages data from a longitudinal cohort of teen mothers and their children to fill these gaps by examining the role of parental behavior as a mechanism underlying the young mother's exposure to adversity and their children's marijuana use in adolescence (age 17 years). We hypothesize that maternal childhood adversity will be associated with increased mental distress, which will in turn be associated with an increase in harsh parenting behaviors. In addition, we expect that maternal harsh parenting behavior will be associated with an increase in children's marijuana use in adolescence. We also hypothesize that there will be gender differences in the link between harsh parenting behavior and adolescent marijuana use behaviors. Given that the literature is mixed with regard to directionality for gender variations in these relationships, this study's aim is exploratory (with no directional hypothesis). Expanding these lines of inquiry will extend the literature on the intergenerational transmission of risk, provide information on possible mechanisms to target to mitigate the intergenerational influence of childhood adversity, and inform the design of relevant interventions.

2 METHODS

2.1 Data and participants

The data were from the Young Women and Child Development Study (YCDS), a longitudinal panel study involving a community sample of pregnant and parenting adolescent mothers (Oxford et al., 2010). Mother–child dyads were followed for 17 years (N = 240); sample retention rates were consistently high across study years, averaging 94.6% (Lee et al., 2022). The sample was racially diverse (48.8% White, 27.1% African American, and 24.1% mixed or other racial groups). To be eligible, participants had to be younger than 18 years old at the time of enrollment, not married, planning to bear and parent the child, and able to speak English. Data collection began in 1987 and ended in 2007. Participants completed study measures during in-person home visits. For participants who moved out of the area, study measures were completed via telephone. Recruitment for this study occurred in public and private hospital prenatal clinics, public school alternative programs, and social services in three counties of a metropolitan region in Washington State, and 76% of eligible adolescents agreed to participate (Oxford et al., 2010). Parent or guardian consent was obtained for participants who were minors. Overall, there were low levels of missing data in this sample. Data were missing for harsh parenting (10.4%), externalizing (8.3), and gender (2.2%), but there were no missing data in maternal childhood adversity or adolescent substance use. The current analysis focused on three data collection points (when the children were 10.5 years old [Time 13], 15 years old [Time 15], and 17 years old [Time 17]). The study and data collection procedures were approved by the human subject review committees at the affiliated universities.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Teen mother's childhood adversity

Childhood adversity was informed by the Adverse Childhood Experience study (Anda et al., 2002) and the emerging literature, suggesting the need to add more items assessing other adversity constructs (Afifi, 2020). Within the existing data set, nine items were used to represent mothers' childhood adversity: (a) physical abuse (Did parents ever throw something at you, push, grab shove, or slap you?); (b) sexual abuse (Have you ever been forced to have sexual intercourse against your will?); (c) emotional abuse (Have you ever been put down by your parents?); (d) foster care experience; (e) food insecurity (How often have you worried about having enough food for yourself?); (f) parental divorce (Were your parents divorced?); (g) parental alcohol use (Did you ever live with an alcoholic parent or parent figure?); (h) death of a parent; and (i) parental arrest (Were your parents arrested?). Childhood adversity for mothers was examined before age 19.5 years (Time 5), except for three retrospective items about physical abuse, being in foster care in childhood, and parental substance use, which were asked at later time points. Each childhood adversity exposure was coded as “1” (yes) versus “0” (no). The total childhood adversity score was computed as a sum score and ranged from 0 to 8. The items were as used as a continuous variable in the model. All items were based on parent self-report.

2.2.2 Maternal mental health

Maternal depression, anxiety, interpersonal sensitivity, and hostility were assessed using their self-reported responses to subscales from the Brief Symptom Inventory, a standardized instrument with demonstrated reliability and validity that was designed to assess psychological functioning (Derogatis, 1992). Each item was scored on a 5-point scale of distress ranging from 0 to 4 (0 = not at all, 1 = a little bit, 2 = moderately, 3 = quite a bit, 4 = extremely). In the YCDS data, each subscale demonstrated solid internal consistency reliability: depression (α = .85); anxiety (α = .78); interpersonal sensitivity (α = .66); and hostility (α = .75). Maternal mental health was measured at child age 10.5 years (Time 13).

2.2.3 Harsh parenting behavior

Harsh parenting was measured using 13 items from the Conflict Tactics Scale, a validated measure to assess parents' punitive discipline, spanking, and physical aggression toward their children (Strassberg et al., 1994). Responses were based on parent self-report. The frequency of each parenting behavior during the past 6 months was rated on a 7-point scale, ranging from 0 to 6 (0 = never, 1 = less than once a month, 2 = once a month, 3 = 2–3 times a month, 4 = once a week, 5 = 2–5 times a week, 6 = everyday). This study utilized the sum of the total responses across the 13 items for conflict tactics (α = .73). Harsh Parenting Behavior was measured at child age 15 years (Time 15).

2.2.4 Adolescent marijuana use

Adolescent marijuana use was measured by adolescents self-reporting the number of times youth reported using marijuana in the past 6 months and was assessed on a scale of 0 to 7 (0 = no use in the past 6 months, 1 = less than once a month; 2 = about once a month, 3 = less than once a week, 4 = about once a week; 5 = two to five times a week; 6 = every day or nearly every day, and 7 = more than once a day). Adolescent marijuana use was measured at child age 17 years (Time 17).

2.2.5 Covariates

Covariates included teen mothers' race (1 = White, 0 = non-White), parents' educational attainment (High school dropout = 0 vs. High school graduate and above = 1), child gender (male = 0; female = 1), and child's externalizing problems, a well-known earlier precursor for later substance use. This was assessed using the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Edelbrock 1991) at age 4.5 years (the earliest assessment available).

2.3 Analytic approach

The current study examined the link between maternal childhood adversity and offspring's marijuana use behavior. The hypotheses for the present study were tested using Structural Equation Modeling, a general linear model to be estimated from the covariance matrix of variables (Bollen, 1989). Following the previously established guideline (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988; Bollen, 1989), a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted first to evaluate the factor loadings and their statistical significance of a latent variable (i.e., maternal mental health in the current study). The benefit of creating a latent variable is that latent factors help control for measurement error. Thus, using the latent factor established in the CFA, we tested hypothesized paths among maternal childhood adversity and adolescent marijuana use via maternal mental health and harsh parenting.

A multiple-group analysis was conducted to evaluate potential gender differences in the link between maternal harsh parenting and adolescent marijuana use. Gender differences across the two models were examined using a Wald's test (Muthén & Muthén, 1998, 2017). For all the models, multiple fit was evaluated using χ2 comparative fit index (CFI ≥ 0.95), and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.06 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). All the analyses were conducted in Mplus version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017, 1998). All covariates were included in all models. The results presented are standardized estimates relative to both independent and dependent variables. Missing data were managed with full information likelihood estimation (Schlomer et al., 2010).

3 RESULTS

Descriptive statistics for the variables and sample demographics are shown in Table 1.

| n% or Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Child sex | ||

| Male | 137 (59%) | |

| Female | 96 (41%) | |

| Child's age | 17 (0.12) | |

| Child marijuana use | 1.42 (2.1) | 0–7 |

| Maternal age at childbirth | 16 (1.01) | |

| Teen mothers' race | ||

| White | 117 (48.75) | |

| African American | 65 (27.08) | |

| Native American | 16 (6.67) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 10 (4.17) | |

| Others | 44 (20.1) | |

| Mother's level of education (grade) | ||

| <High school | 169 (73.8) | |

| High school (9–12) | 60 (26.2) | |

| Mothers childhood adversity | ||

| Maternal mental Health | ||

| Depression | 0.62 (0.73) | 0–4 |

| Anxiety | 0.58 (0.75) | 0–4 |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 0.60 (0.76) | 0–4 |

| Hostility | 0.65 (0.77) | 0–4 |

| Harsh parenting | 13.95 (10.86) | 0–43 |

| Children's externalizing behavior | 56.56 (10.59) | 30–88 |

| Maternal childhood adversity | ||

| 0 | 14 (5.8%) | |

| 1 | 45 (18.8%) | |

| 2 | 55 (22.9%) | |

| 3 | 46 (19.2%) | |

| 4 | 44 (18.3%) | |

| 5 | 24 (10.0%) | |

| 6 | 9 (3.8%) | |

| 7 | 3 (1.3%) | |

| Total Maternal Adversity Score | 2.8 (1.6) | 0–8 |

The mean score for marijuana use was 1.42, indicating that, on average, youth are using marijuana less than once per month. The mean childhood adversity score for teen mothers was 2.84, indicating that, on average, teen mothers reported close to three adverse experiences. The mean score for harsh parenting was 13.95, suggesting that less than once a month, teen mothers were harsh towards their children. Mean mental health scores were: depression (0.62), anxiety (0.58), interpersonal sensitivity (0.60), and hostility (0.65). These suggest the teen mothers were a bit depressed, anxious, hostile, and had low interpersonal sensitivity. More than half of the children were boys (59%). Table 2 shows the full details of the bivariate correlations between the study items.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maternal Childhood adversity | ||||||||||

| 2. Adolescent substance use | −.02 | |||||||||

| 3. Harsh Parenting | .06 | .34*** | ||||||||

| 4. Depression | .30*** | .03 | .18* | |||||||

| 5. Anxiety | .29*** | −.02 | .24** | .72*** | ||||||

| 6. Hostility | .21** | .06 | .25** | .58*** | .60*** | |||||

| 7. Interpersonal sensitivity | .26*** | −.03 | .21** | .72*** | .77*** | .60*** | ||||

| 8. Gender | −.07 | −.11* | −.01 | −.02 | −.12 | −.05 | −.03 | |||

| 9. Externalizing | .27*** | .08* | .37*** | .31*** | .32*** | .30*** | .32*** | −.14 | ||

| 10. Race | .14* | −.05 | −.05 | .08 | .05 | .06 | .05 | −.08 | .03 | |

- *** p < .001

- ** p < .01

- * p < .05.

3.1 Evaluation of the pathways

CFA was conducted to evaluate the factor loadings of a latent variable, maternal mental health, using anxiety, depression, interpersonal sensitivity, and hostility variables as indicators. All indicators had high factor loadings (β = .69, −.89) and were statistically significant (p < .001), empirically confirming the latent construct.

Next, the hypothesized paths were estimated to examine the link between maternal childhood adversity, maternal mental health, parenting behavior, and their adolescent children's marijuana use behaviors (see Figure 1). The model fit the data well (χ2 [36] = 44.862, p = 0.1477, RMSEA = 0.03, CFI = 0.98) and explained 14% of the variance in adolescent marijuana use. Maternal childhood adversity was associated with an increase in mental health problems (β = .32, p < .001). In turn, maternal mental health problems were predictive of mothers' harsh parenting (β = .27, p < .01), which then eventually predicted adolescents' marijuana use (β = .34, p < .001). A significant indirect path was found from maternal childhood adversity via maternal mental health and parenting behaviors to youth marijuana use at age 17 years (β = .03, p < .05) in the full group.

Further, possible gender differences were examined in the path from harsh parenting to marijuana use among youth. Multiple-group analysis revealed that there were gender differences in the path from maternal harsh parenting to youth's marijuana use (Wald's test χ2[1] = 4.82, p < .05). The path from harsh parenting behavior to their children's marijuana use behavior for boys was statistically significant (β = .42, p < .001), whereas it was not for girls.

4 DISCUSSION

The harmful impacts of childhood adversity have been found to trickle down to the next generation and play a role in shaping children's behavioral health (Schickedanz et al., 2018; Yoon et al., 2019). However, despite the increase in the number of existing studies focusing on the impact of childhood adversity, few have focused on the intergenerational impact of maternal childhood adversity on their offspring beyond early childhood. Additionally, no prior studies have explicitly focused on the mechanisms underlying marijuana use among children born to teen mothers with childhood adversity. To address these gaps, the present study used the Family Stress Model (Masarik & Conger, 2017) as a framework to examine maternal mental health and harsh parenting as mechanisms underlying the association between maternal childhood adversity and their children's marijuana use at age 17 years. Subsequent multigroup analysis was used to examine whether the influence of mothers' harsh parenting on their children's marijuana use differed across genders.

Maternal mental health emerged as a mechanism linking maternal childhood adversity to mothers' parenting behaviors in this present study. This may be because childhood adversity can disrupt the acquisition of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral capacities that are essential for healthy and nurturing parenting (Madsen et al., 2022). Maternal distress can negatively influence parenting behaviors or interactions with their children (Tracy et al., 2019), leading to children engaging in negative coping behaviors, such as marijuana use (Kelley et al., 2015).

As posited in the Family Stress Model (Masarik & Conger, 2017), the study also found maternal harsh parenting as a mechanism that links maternal mental health to adolescent marijuana use. During adolescence when the developing brain is more impacted by environmental signals and stressors (Dahl & Gunnar, 2009), harsh parenting may result in elevated responsiveness to stress (Copeland et al., 2019). When adolescents experience these types of stressors, negative coping, including marijuana use (Rogosch et al., 2010; Spear, 2015) may be used as an attempt to minimize stress. Further, the developmental period of late adolescence represents a period of transition to emerging adulthood. This transition period features dynamic changes in their lives (Dahl & Gunnar, 2009) and is an essential period for targeted interventions. Although our study focused on harsh parenting, other important dimensions of parenting should be considered in future work. For example, lower parental monitoring has been linked to youth marijuana use in prior work (Rusby et al., 2018; Ruybal & Crano, 2020), suggesting that parental monitoring, along with communication (Patel et al., 2021) and role modeling (O'Loughlin et al., 2019) may be important to better understand the relationships between maternal childhood adversity experiences and adolescent substance use. Additionally, future studies may expand this model by including adolescents' own adversity experiences as another mediating pathway.

The study also examined possible gender differences in the hypothesized path from parenting behaviors to children's marijuana use. We found gender differences in the path from harsh parenting behaviors to children's marijuana use, with boys at higher risk for marijuana use behaviors as compared to girls. This may be due to the biologically based sex-differentiated reactivity patterns and self-endorsement of gendered norms (which discourage emotionality in boys and encourage it in girls; Hammerslag & Gulley, 2016). This finding supports the gender strain theory (Broidy & Agnew, 1997) and the gender socialization hypothesis, which suggests that response to distress tends to vary by gender and this often results in distinct pathways in behavioral health. Thus, in response to the distress, girls are more likely to internalize (Gutman & McMaster, 2020), whereas boys may be more likely to externalize, such as the use of marijuana (Hammerslag & Gulley, 2016). Additionally, adolescence is a period where gender norms become more recognized (Kågesten et al., 2016) and gendered behavior intensifies (Hill & Lynch, 1983). This may result in more distinct gendered patterns in behavioral health outcomes resulting in more distinct gendered patterns in behavioral health outcomes (Gutman & McMaster, 2020), such as boys utilizing marijuana, as a form of coping with their stressful home environment.

There are some limitations to this study. First, measures on teen mothers' childhood adversities relied on teen mothers' self-reports, creating the possibility of reporting errors or biases, including memory bias and response bias. Additionally, adolescent substance use behaviors represent illegal behaviors, thus respondents may not be willing to respond truthfully due to social desirability. Furthermore, this study focuses on a specific population of teen mothers and their adolescent offspring. Also, because teen mothers are more likely than older mothers to live with their family of origin and/or get greater support from family after the birth of their child (Pasalich et al., 2016), the intergenerational impact of childhood adversity may have differential impacts on the children of teen mothers. As such, the generalization of our study findings to families with different demographic characteristics should be carried out cautiously.

Despite its limitations, this study made significant contributions to extant literature. First, the study examined the intergenerational impact of maternal childhood adversity on their children beyond early childhood. Additionally, the study highlights mechanisms such as maternal mental health and parenting as mechanisms linking maternal adversity to adolescent marijuana use. Further, the study examined gender variations in the link between maternal harsh parenting (stemming from childhood adversity) and adolescent marijuana use, locating a subgroup of children born to teen mothers with heightened vulnerability.

4.1 Conclusion

The study findings shed light on underlying parenting mechanisms linking teen mother's childhood adversity to their offspring's marijuana use and suggest that children of teen mothers with prior exposure to adversities (such as maltreatment, poverty, parent's divorce, and parent's substance abuse) are at increased risk for poor behavioral outcomes. It is critical to understand the impact of early childhood adversity, not only its short-term contributory role to parental mental health but also the long-term cascading impact on parental behavior and children's behavioral outcomes such as marijuana use behaviors. These findings have implications for prevention efforts in highlighting parenting mechanisms linking teen mothers' childhood adversity to their offspring's marijuana use behavior.

To mitigate the adverse impact of childhood adversity, there is a need to examine and address the factors contributing to maternal childhood adversity. Additionally, there is a need to provide support for teen mothers with a history of childhood adversity to help mitigate risks for their children. Bolstering positive parenting practices and parenting skills (Park et al., 2018) and early prevention efforts aimed at promoting maternal mental health might be effective strategies to disrupt the intergenerational impact of adversity.

In supporting adolescents exposed to stressful home environments, it would be important to provide them with social-emotional learning skills (Taylor et al., 2017), which can enable them to develop positive coping skills. Also, there is a need to have partnerships with parents and utilize family-centered treatments when working with adolescents who use marijuana. Finally, the development of interventions and treatments that are specific to the gendered impacts of harsh parenting behavior or stressful home environments might also be essential for more effective outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to extend our gratitude to the YCDS study participants for their contribution to the study. This study was supported by grants HD097379 from National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, DA05208 from National Institute on Drug Abuse, and MH52400 and MH56599 from National Institute of Mental Health. The content of this study is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies. The funding agencies played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit this article for publication.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.