The longitudinal relationship between social support and victimization among latino teens

Abstract

Purpose

This study examines the relationship between social support and victimization of Latino youth over time, utilizing the stress prevention and support deterioration models.

Methods

To address the research questions we utilized data from Waves 1 and 2 (n = 574) of the Dating Violence among Latino Adolescents (DAVILA) study, a national bilingual phone survey of self-identified Latino youth and their caregiver. Cross-lagged panel modeling was used to assess the fit of the two theoretical models to observed patterns of covariance among the victimization and social support variables specified.

Results

Results show that victimization at Wave 1 was positively and strongly related to victimization at Wave 2 and social support at Wave 1 was positively and moderately associated with social support at Wave 2. As hypothesized, higher levels of victimization at Wave 1 were significantly related to decreases in social support at Wave 2 (β = −.15). Wave 1 social support was not significantly related to victimization at Wave 2.

Conclusions

We did not find support for the stress prevention model but did find support for the support deterioration model. Teens who were victimized tended to have lower levels of subsequent social support, highlighting the need to equip peers, family, and significant others to adequately respond to victimization disclosures.

1 INTRODUCTION

The overall rates of youth victimization in the United States are high. According to the most recent Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), 22%, 14%, and 11% of youth experienced bullying, dating violence, and sexual violence, respectively, in the last year (Clayton et al., 2023). Expanding the definition of youth victimization to include victimizations such as child maltreatment, conventional crime, and witnessing violence, another national study found upwards of 55% of youth were exposed to violence in the past year (Finkelhor et al., 2015). Latino youth experienced similar levels of sexual and dating violence as other racial/ethnic groups and significantly lower levels of bullying than White youth according to the recent YRBS data (Clayton et al., 2023). Another national study that was specifically developed for Latinos, employed a broad definition of violence, and was longitudinal—the Dating Violence among Latino Adolescents (DAVILA) study—found 53% of Latino youth were victimized at the first wave—37% peer and sibling victimization, 19.5% dating victimization, 18% conventional crime, 18% child maltreatment, and 5% stalking (Cuevas et al., 2014). Wave 2 data highlighted how victimization at Wave 1 was associated with elevated risk of victimization at Wave 2 (Cuevas et al., 2020; Sabina et al., 2016).

The pervasiveness of youth victimization becomes more alarming when we consider the increased risk of emotional troubles (e.g., anxiety, depression, loneliness), physical health problems (e.g., somatic symptoms, sleep, stress response), and future suicidal ideation, criminal behavior, and substance misuse it causes (Schacter, 2021; van Geel et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2015). While Latino youth do not appear to be at heightened risk of victimization, there is longitudinal evidence from prospective data that Latino youth who are victimized are more likely to also be victimized in adulthood compared to Whites (Halpern et al., 2009). Other studies have also noted unique victimization trajectories of Latinos, which are associated with prolonged risk (Semenza et al., 2022) and unique victimization profiles of youth that combine victimization with loss (Adams et al., 2016) and sexual violence (Holt et al., 2017). In the interest of health and well-being of youth, it is important to examine the potential mechanisms that disrupt the relationship between victimization experiences over time.

A potential mechanism is perceived social support; the cognitive appraisal of being loved and esteemed and the confidence that help will be available if needed (Turner et al., 1983). The beneficial impact of social support on youth's overall well-being, regardless of victimization status, is well documented. A meta-analysis of studies focused on youth found influences on self-concept, health (e.g., exercise, healthy habits), social adjustment (e.g., popularity, cooperativeness), conduct (e.g., misbehavior, delinquency), psychological adjustment (e.g., depression, anxiety, happiness), and academic achievement (Chu et al., 2010). Within the context of resilience research, the possible buffering effect of social support has been studied among youth who have been victimized. While not universal, several studies have found that social support alleviates the negative consequences associated with victimization for youth overall (Folger & Wright, 2013; Holt & Espelage, 2005; Richards & Branch, 2012; Schacter et al., 2021; Tucker et al., 2020), supporting the stress-buffering model. Nonetheless, several studies have found a nonsignificant or limited relationship between social support and well-being after adversity (Burke et al., 2017; Richards et al., 2014; Rothon et al., 2011). The majority of research on the role of social support in victimization probes its role in mitigating the consequences of violence. Yet, another possibility is that social support could affect victimization exposure directly. A recent meta-analysis found that both peer and parental support were associated with a significant but small decrease in the risk of dating violence victimization (Hébert et al., 2019). Therefore, this study examines the relationship between social support and victimization over time using data from a national sample of Latino youth.

2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS

Given the complex relationships between social support, stress (e.g., victimization exposure), and distress (e.g., mental health), Barrera (1986) identified several models to more precisely define these relationships. Of interest to the current study is how social support is related to stress (not distress), which is less often examined than the buffering role of social support and is a current gap in the research (Uchino & Birmingham, 2011). Theoretically, stress could trigger the mobilization of social support, such that stress and social support would be positively correlated. Here victimization would be met with increased social support over time. Another possibility is that social support is negatively related to stress. This could occur in two ways as defined by the stress prevention model and the support deterioration model. In the stress prevention model, social support affects a stressful situation by either preventing its occurrence or decreasing its perceived harmfulness after it occurs (Barrera, 1986). Recent work on thriving in relationships (Feeney & Collins, 2015) theorizes positive interpersonal connections lead to personal growth and encourage the pursuit of and involvement in opportunities that enhance personal well-being. More specifically an individual may increase positive emotions, self-confidence, and better assess opportunities thus promoting healthier lifestyles such as decreased use of alcohol and other substances and fewer risky behaviors (Feeney & Collins, 2015). Social support can also reduce negative feelings, such as, fear, anxiety, and helplessness, and increase self-acceptance, coping strategies, and self-regulation after adversity (Feeney & Collins, 2015), which may also lead to a decreased risk of revictimization. Although the mechanisms by which social support influences victimization is not often examined, there is some empirical support in the victimization literature for the stress prevention model. For example, longitudinal studies have found a negative association between peer support and future peer victimization (Boulton et al., 1999) and emotional dating violence victimization (Richards et al., 2014), as well as between childhood parental support and teen dating violence victimization (Maas et al., 2010).

Barrera's (1986) support deterioration model, by contrast, points to the impact that a stressful experience has on perceived social support. That is, stressful experiences may diminish the perceived availability or helpfulness of social support. Barrera (1986) identified mechanisms through which this could occur. Distress could create poor perceived social support through the distortion of actual social support. Peers could reject individuals showing signs of distress. Finally, distress can also cause poor socialization skills and exacerbate mental health disorders that could thin the victim's social network or cut back its quality. Studies supporting this model, albeit limited, have emerged in recent years. For instance, in a panel data study of middle school students, researchers found that bully victimization was inversely related to perceptions of parent support 1 year later (Smokowski et al., 2014). Other studies have explored the association between victimization and peer social network, a measure of connectedness (Wallace & Ménard, 2017), and potentially, peer support. These studies indicated that among adolescents, experiencing conventional crime victimization was associated with a decrease in the number of reported friends over time (Wallace & Ménard, 2017) and experiencing sexual victimization was negatively associated with connectedness to friendship networks 7 years later (Tomlinson et al., 2021).

Barrera's (1986) models of stress prevention and support deterioration, as well as the empirical evidence, suggest that a reciprocal relationship between victimization and perceived social support is plausible. That is, experiencing victimization may decrease the perceived helpfulness of social support (support deterioration model), and social support may serve as a protective factor against victimization (stress prevention model). Unfortunately, the majority of studies on victimization and social support have utilized cross-sectional data limiting the analysis of temporal sequencing and obscuring the casual relationship between victimization and social support. Longitudinal data is best to examine these potentially reciprocal relationships (Uchino & Birmingham, 2011). To the best of our knowledge, only three studies have explored the longitudinal reciprocal relationship between social support and victimization (Burke et al., 2017; Kendrick et al., 2012; Lester et al., 2013). Inconsistencies in the bidirectional relationship between victimization and social support were found in these studies that warrant further exploration.

2.1 Longitudinal studies on youth victimization and social support

Although the literature on youth victimization could benefit from researchers exploring the effects of perceived social support on victimization and victimization on perceived social support over time, few researchers have assessed their longitudinal impact. Underlining this point, a recent meta-analysis on the association between peer and family risk and protective factors and dating violence found that both peer support and parent support were associated with less dating violence victimization, but these associations were unable to be studied with longitudinal studies given the insufficient number of studies (Hébert et al., 2019). Three studies that examined this bidirectional relationship used both long-term and short-term longitudinal data and structural equation modeling, specifically cross-lagged models to enable the statistical testing of causal paths (Burke et al., 2017; Kendrick et al., 2012; Lester et al., 2013).

In their study, Kendrick and colleagues (2012) examined two waves of data for approximately 1 year. They found that an increase in perceived peer social support at time one was related to a decrease in bullying victimization at time two (stress prevention). However, the reciprocal relationship, although it was negative, was not statistically significant. Similarly, Lester et al. (2013) found that higher perceived peer support was associated with less bullying victimization (stress prevention), and this association persisted across their three data collection points, which included the years of 2005–2007. They also found the reciprocal relationship to be significant. That is, an increase in bullying victimization was associated with a decrease in perceived peer support (support deterioration). Burke et al. (2017), on the other hand, did not find a statistically significant longitudinal association between peer victimization and perceived parental support measured over 2 years (2010–2012); no analysis was conducted on peer victimization and peer support due to poor model fit.

While these studies provide insight into the relationship between victimization and social support, more research is needed. An exploration of the relationship between social support and victimization is of particular importance in the Latino community where family and social networks play a key role in youth development (DeGarmo & Martinez, 2006; Hernández & Bámaca-Colbert, 2016). Yet, there has been no study that examines the longitudinal bidirectionality association between social support and victimization among Latino youth.

2.2 Social support and Latino youth

Social support networks are an integral component in the lives of Latino youth (Hernández & Bámaca-Colbert, 2016). The Latino community tends to embrace collective values, including familism and social networks. Generally, familism or support for the family unity and connectedness has been found to promote positive psychological adjustment and school engagement among Latino youth (Stein et al., 2015). Similarly, social networks have been shown to have a positive impact on Latino youth's health (Marquez et al., 2014).

In relation to victimization, nonetheless, studies of social support among Latino youth are limited. One cross-sectional study with this population indicated that victims of bullying had less social support from their peers, but not from their parents, than those who were not involved in bullying (Demaray & Malecki, 2003). Another cross-sectional study with Latino youth explored related concepts: perceived parental caring and parent connectedness and their association with dating violence victimization (Kast et al., 2016). Kast et al. (2016) found that although both factors protect Latino youth against dating violence victimization, perceived parent caring was the most critical factor in reducing the risk for physical and sexual dating violence. Because of the paucity of studies that focus on social support and victimization among Latino youth, research exploring the relationship between these variables is critical. This is especially true since the Latino population, a fast-growing one, is made up of almost 33% youth (Patten, 2016).

2.3 The current study

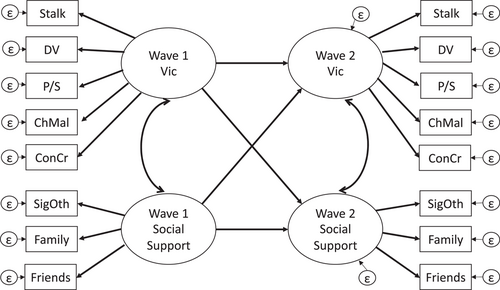

Latino youth are at risk of a range of victimizations that threaten their well-being. While it is clear that social support buffers the relationships between victimization and well-being, it is unclear how social support is linked to victimization, especially over time. Given the limited body of research on these relationships, the present study examined the reciprocal relationship between social support and victimization using a longitudinal study and cross-lagged Structural Equation Model (SEM), as shown in Figure 1. This study sought to examine if Latino youth's victimization experiences at Wave 1 predicted perceived social support at Wave 2, accounting for the concurrent association between victimization and perceived social support. Additionally, the reciprocal relationship—if Latino youth's perceived social support at Wave 1 predicted victimization experiences at Wave 2 accounting for the concurrent association between victimization and perceived social support—was examined. We hypothesized that experiencing victimization would lead to lower levels of perceived social support and higher levels of perceived social support would lead to reporting less victimization across time in line with the stress prevention and support deterioration models.

3 METHODS

To address the research questions, we utilized data from Waves 1 and 2 (n = 574) of the Dating Violence among Latino Adolescents (DAVILA) study (Cuevas et al., 2015). DAVILA was a national bilingual phone survey of self-identified Latino youth (ages 12–18) and their caregiver. Wave 1 data was collected from September 2011 to February 2012 and those who agreed to be re-contacted (n = 1427) were reinterviewed from February 2012 to August 2013, with an average of 15.5 months between waves. The Wave 1 response rate (RR4) was 36%, Wave 1 cooperation rate (COOP4) was 55%, and the retention rate from Wave 1 to Wave 2 was 40.2%. For these analyses, only youth who participated in both Waves of data are included (n = 572). Youth tended to complete the Wave 2 survey in English (83.8%), while most caregivers preferred to be interviewed in Spanish (85.7%).

At Wave 1, youth were 14.74 years old on average (SD = 1.81) and at Wave 2 youth were 16.50 years old on average (SD = 1.89). See Table 1 for full demographic information. At Wave 2, 19% of the sample was no longer in grade school. Parents tended to have high school level educations or less (69.3%) and be married (70.6%). The most common form of victimization in Wave 1 (27%) and Wave 2 (19.7%) was peer/sibling victimization. Other papers have addressed victimization rates (Cuevas et al., 2014, 2020; Mariscal et al., 2021; Sabina et al., 2016).

| Study variables | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victimization | n | % | n | % |

| Conventional crime | 82 | 14.29 | 70 | 12.20 |

| Child maltreatment | 74 | 12.89 | 60 | 10.45 |

| Peer/sibling victimization | 157 | 27.35 | 113 | 19.69 |

| Sexual victimization | 17 | 2.96 | 20 | 3.48 |

| Stalking | 39 | 6.79 | 29 | 5.05 |

| Dating violence | 71 | 12.37 | 99 | 17.25 |

| Social support | n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) |

| Friends | 574 | 6.18 (1.18) | 574 | 5.92 (1.62) |

| Family | 574 | 6.21 (1.15) | 574 | 6.07 (1.21) |

| Significant other | 574 | 5.93 (1.24) | 574 | 6.27 (1.50) |

| Adolescent demographics | n | % | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 12 | 77 | 13.41 | 2 | 0.35 |

| 13 | 92 | 16.03 | 59 | 10.28 |

| 14 | 103 | 17.94 | 79 | 13.76 |

| 15 | 86 | 14.98 | 105 | 18.29 |

| 16 | 99 | 17.25 | 93 | 16.20 |

| 17 | 82 | 14.29 | 97 | 16.90 |

| 18 | 35 | 6.10 | 88 | 15.38 |

| 19 | 41 | 7.14 | ||

| 20 | 10 | 1.74 | ||

| Grade | ||||

| 6th | 24 | 4.20 | ||

| 7th | 79 | 13.84 | 24 | 4.18 |

| 8th | 92 | 16.11 | 55 | 9.58 |

| 9th | 105 | 18.39 | 104 | 18.11 |

| 10th | 98 | 17.16 | 99 | 17.25 |

| 11th | 75 | 13.13 | 102 | 17.77 |

| 12th | 79 | 13.84 | 80 | 13.93 |

| H.S. graduate | 16 | 2.80 | 30 | 5.23 |

| Home schooled | 1 | 0.18 | 1 | 0.17 |

| Not in school | 2 | 0.35 | 71 | 12.36 |

| Other | 8 | 1.39 | ||

| Genderb | ||||

| Girls | 304 | 52.96 | ||

| Boys | 270 | 47.04 | ||

| Birth countyb | ||||

| US born citizen | 416 | 72.72 | ||

| Mexico | 112 | 19.58 | ||

| Other | 44 | 7.69 | ||

| Generational statusa, b | ||||

| Immigrant/first generation | 156 | 27.32 | ||

| Second generation | 344 | 60.25 | ||

| Third generation | 44 | 7.71 | ||

| Fourth generation | 27 | 4.73 | ||

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Straight/heterosexual | 534 | 94.18 | 544 | 94.77 |

| Gay/lesbian | 2 | 0.35 | 5 | 0.87 |

| Bisexual | 8 | 1.41 | 11 | 1.92 |

| Not sure/in transition | 23 | 4.06 | 13 | 2.26 |

| Household/parent demographics | n | % | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household income | ||||

| Under $9999 | 64 | 13.62 | 77 | 14.10 |

| $10,000–$19,999 | 125 | 26.60 | 159 | 29.12 |

| $20,000–$29,999 | 106 | 22.55 | 130 | 23.81 |

| $30,000–$39,999 | 52 | 11.06 | 66 | 12.09 |

| $40,000–$49,999 | 50 | 10.64 | 45 | 8.24 |

| $50,000–$59,999 | 23 | 4.89 | 25 | 4.58 |

| $60,000–$69,999 | 12 | 2.55 | 10 | 1.83 |

| $70,000–$79,999 | 8 | 1.70 | 8 | 1.47 |

| $80,000 or more | 30 | 6.38 | 6 | 4.76 |

| Parent educational levelb | ||||

| Less than high school | 203 | 35.61 | ||

| High school graduate | 192 | 33.68 | ||

| Some college/trade school | 65 | 11.40 | ||

| Two-year college graduate | 35 | 6.14 | ||

| Four-year college graduate | 49 | 8.60 | ||

| Some graduate school | 4 | 0.70 | ||

| Graduate degree | 22 | 3.86 | ||

| Parent relationship statusb | ||||

| Single (never married) | 61 | 10.63 | 45 | 7.87 |

| Married | 410 | 71.43 | 404 | 70.63 |

| Cohabitating/committed relationship/dating | 50 | 8.72 | 60 | 10.49 |

| Divorced/separated/widow/other | 52 | 9.08 | 63 | 11.01 |

- a Immigrant/1st generation = child born abroad, second generation = parent born abroad, third generation = 1 or more grandparents born abroad, fourth generation = neither grandparent born abroad.

- b Not assessed again at follow-up.

3.1 Measures

3.1.1 Demographic information

Caregivers provided information about youth's age, parent's age, country of origin and/or descent, immigration status, parent's educational level, employment status, household income, household makeup, and parental relationship status. The adolescent provided information on grade level, employment, sexual orientation, and past-year dating history. Four demographic variables were included in the later primary analyses including gender self-identification (boy or girl), age (in years between 12 and 18), parent's educational level (less than high school, high school, some college or trade school, 2-year college graduate, 4-year college graduate, some graduate school, graduate degree), and household income (under $10,000, $10,000–19,900, $20,000–29,000, $30,000–39,000, $40,000–49,000, $50,000–59,000, $60,000–69,000, $70,000–79,000, and above $80,000).

3.1.2 Juvenile victimization questionnaire (JVQ)

The JVQ comprehensively evaluates childhood victimization (Hamby et al., 2005). The instrument contains 34 screener questions that cover five general areas of victimization: conventional crime, child maltreatment, peer and sibling victimization, sexual assault, and witnessing and indirect victimization. Adolescent participants responded to a modified version tapping 16 original screeners and one about stalking, thus totaling 17 screener questions. “Time bounding” was used to help participants define the past year. An affirmative response to each screener was coded as a 1; a negative response 0. Screeners answered affirmatively were followed up with additional questions including the relationship to perpetrator. Any violent act perpetrated by a boyfriend/girlfriend or date were coded as dating violence victimization and combined with CTS2S responses (see below). The JVQ used test-retest reliability and has established validity through its association with trauma symptomatology (Hamby et al., 2005). For this study, Cronbach's α was .68.

3.1.3 The Conflict Tactics Scale 2 short form (CTS2S)

The CTS2S was modeled after the CTS2, using only two items from each of the subscales, one focusing on severe behavior, the other on less severe behavior (Straus & Douglas, 2004). Twelve of the 20 CTS2S items were used in the DAVILA study due to time constraints. For this study, the CTS2S was only administered to any adolescent participant that indicated having had a boyfriend/girlfriend or dating partner in the past year. If any of the responses to these items were positive, we coded the participant as having experienced dating violence (1). Thus, dating violence victimization was ascertained via any affirmative CTS2S response or any affirmative JVQ response that was indicated to be perpetrated by a boyfriend/girlfriend or date. The CTS2S has good psychometric properties with high correlations with the full CTS2, ranging between .64 and .94 for victimization and perpetration behaviors (Straus & Douglas, 2004). For this study, Cronbach's α was .70.

3.1.4 Multidimensional Scale of perceived social support (MSPSS)

The MSPSS includes 12 items assessing social support from significant others, family, and friends (Zimet et al., 1988). Adolescent participants were asked to respond to each item on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree). Zimet and colleagues (Zimet et al., 1988) found the MSPSS to have an overall reliability of 0.88, with reliabilities of 0.91, 0.87, 0.85 for the significant other, family, and friend subscales, respectively. The overall reliability coefficient for our sample was .90 during Wave 1.

3.2 Procedures

Trained women professionals from an experienced survey research firm conducted the interviews over the phone with a computer assisted telephone interview (CATI) system. While the study began with a national random digit dialing (RDD) sample of high-density Latino neighborhoods (n = 111), the large majority of the sample was gleaned from randomly selected telephone numbers from a list of Latino surnames (n = 1414) to improve efficiency. These two sources of data were combined. Potential participants were asked how many Latino or Hispanic children under the age of 18 live in the home. If there was one child in the home, that child was selected for the interview. If there were multiple children, the one with the most recent birthday was selected. The caregivers consented to the study first and then assent was garnered from the adolescent (or consent if over the age of 18) before participating. Parents received a $5 check and youth received a $15 check as compensation for their time during DAVILA-II data collection. All participants were given the contact information for the National Child Abuse Hotline and a Privacy Certificate was obtained protecting forced disclosure. The IRBs of two universities approved the study procedures.

3.2.1 Statistical analysis

Stata software version 17 (StataCorp) was used for all analyses. First, we examined frequency differences between all demographic variables as well as target variables on the basis of gender. Boys (27.9%) experienced conventional crime more frequently than girls (13.8%, χ2 = 25.24, p < .001). Girls (22.3%) experienced child maltreatment and stalking more frequently than boys (13.9%, χ2 = 10.62, p < .001). Girls (7.7%) experienced stalking more frequently than boys (4.7%, χ2 = 4.67, p = .03). No differences were noted between boys and girls on any other victimization variables. Additionally, we examined mean differences between boys and girls on all demographic and target variables using one-way univariate analysis of variance analysis (ANOVA). Girls reported higher levels of social support from significant others compared to boys (Ms = 6.3, 5.9, SDs = 1.06, 1.35, p < .001) as well higher social support from friends (Ms = 6.13, 5.60, SDs = 1.14, 1.46, p < .001), but there were no differences between boys and girls in the demographic variables (all ps > .05). Considering the theoretical issues, gender as well as youth age, parental education status, and household income were included as control variables in all future structural equation modeling. Invariance testing was not performed due to sample size considerations.

Third, preliminary correlational analyses performed between the predictor variables revealed no evidence of multicollinearity (usually defined as a .90 correlation or greater) among the predictor variables (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007), as the highest correlation between predictor variables was .54. Although linear regression analyses were not completed as the primary analytic method in the current study, linear regressions were run between predictor variables and all dependent variables, including collinearity diagnostic procedures, such as the variance inflation factor (VIF). All VIF scores were lower than 5 (VIFs < 5), further indicating no significant multicollinearity present.

Fourth, cross-lagged panel modeling was used to assess the fit of Barrera's two hypothesized theoretical models to observed patterns of covariance among the victimization and social support variables specified in his models (Kline, 2016; Little, 2013). Specifically, we utilized scores from the JVQ and CTS2S to assess victimization and the MSPSS to assess social support. To assess the cross-lagged effects between victimization and social support over time, we modeled the effects of victimization and social support at Wave 1 on social support and victimization at Wave 2 (see Figure 1). Our model also includes associations between victimization levels across time and between social support levels across time (autoregressive paths). We estimated cross-lagged and autoregressive effects controlling for the other (Kline, 2016). The initial analyses included gender as well as youth age, parental education status, and household income as control variables. None of the control variables were significant and thus were removed from the final model for parsimony.

A four-stage recursive process was completed using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) methods (see Kline, 2016; Little, 2013, for reference). First, we completed a measurement model at Wave 1, in other words, modeling the relationships between victimization and social support variables at that wave, only. Then we completed a measurement model at Wave 2, modeling the relationships between victimization and social support variables at that wave, only. Second, we used variables of victimization and social support at Wave 1 to predict variables of victimization and trauma at Wave 2. This was a completely cross-lagged model including covariates of interest: youth age, youth gender, parental education and household income. Third, we trimmed the model, pruning nonsignificant paths. Fourth, we used modification indices and our theoretical model to guide model pruning, balancing parsimony, model fit, and interpretability, as part of our model re-specification process. More specifically, after the model was pruned for nonsignificant paths, we utilized the estat mindices function in STATA to indicate any modification indices above 3.84, which would indicate candidate paths for further fitting. The only candidate paths indicated for further fitting were those that would allow observed social support variables at Wave 1 to predict social support variables at Wave 2, as well as correlations between error terms. The authors met to discuss these suggested changes, found these re-specifications theoretically acceptable and made them, reviewed them, and removed nonsignificant pathways resulting in our final model (see Table 2 for model comparisons).

| Model | χ2 (df) | Comparison | χ2 (df) diff | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Victimization and social support at Wave 1 (measurement model, only; W1) | 181.79 (19), p < .01 | Not applicable | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.91 | 0.87 | |

| 2. Victimization and social support at Wave 2 (measurement model, only; W2) | 129.87 (19), p < .01 | Not applicable | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.83 | 0.75 | |

| 3. Victimization and social support cross-lagged at Wave 1 and Wave 2 w/covariates (Measurement model; At W1 and W2) | 767.97 (154), p < .01 | Not applicable | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.70 | 0.64 | |

| 4. Victimization and social support cross-lagged at Wave 1 and Wave 2, w/covariate of parental education (pruned, cross-lagged model with only significant paths; W1 and W2) | 591.70 (112), p < .01 | 4 v 3 | 176.27 (42), p < .01 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.75 | 0.70 |

| 5. Victimization and social support cross-lagged at Wave 1 and Wave 2, w/covariate of parental education, and correlated social support indicators across Waves (pruned, cross-lagged model with only significant paths and modified per modification indices) | 377.21 (106), p < .01 | 5 v 4 | 214.49 (6), p < .01 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.86 | 0.82 |

| 6. Victimization and social support cross-lagged at Wave 1 and Wave 2, w/covariate of parental education, and correlated social support indicators across waves (cross-lagged model paths, including nonsignificant paths, for example, between observed social support variables, after modified per modification indices and Satorra–Bentler correction for data non-normality) | 281.57 (106), p < .01 | 6 v 3 | 486.4 (48), p < .01 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.86 | 0.83 |

| 7. Victimization cross-lagged at Wave 1 and Wave 2, w/correlated social support residuals (pruned, partially cross-lagged model w/social support path from W1 and victimization W2 removed, social support stability indicator paths removed and Satorra–Bentler correction for data non-normality) | 260.25 (96), p < .01 | 7 v 6 | 21.32 (10), p < .05 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.87 | 0.83 |

- Abbreviations: CFI, the Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; SRMR, the standardized root mean squared residual; TLI, the Tucker Lewis Index.

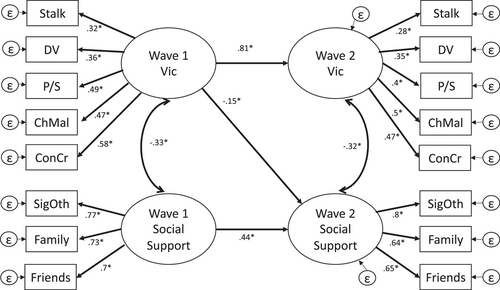

For estimation, we used multiple fit indexes to evaluate model fit, including χ2 statistic, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI). Excellent fit is indicated by RMSEA below 0.06 and acceptable fit is indicated by RMSEA values between 0.05 and 0.08 whereas values greater than 0.08 suggest poor fit. SRMR values below 0.08 are considered good (Ximénez et al., 2022). Generally speaking, CFI and TLI values between 0.90 and 0.95 suggest acceptable fit whereas values smaller than 0.85 suggest poor fit (Little, 2013); however, because we had several factor loadings below 0.6 and one below 0.3, use of the CFI and TLI indices is not recommended (Ximénez et al., 2022) and we included them here only for reference. Thus, the obtained RMSEA and SRMR fit indices for our final model indicated good fit. It is also important to note that due to high levels of skewness and kurtosis the Satorra–Bentler correction was applied to all fit indices of the last model as appropriate to correct for any deviations from normality (Kline, 2016). Because we standardized all the variables, the beta weights indicate the effect size of the predictor variables. Youth age, gender, parental education status, and household income at baseline were included as control variables in the initial model iterations on victimization and social support but none were found to have an effect on victimization at Wave 2 (see Figure 2 for final model).

4 RESULTS

4.1 Cross-Lagged Model

Model fit indices indicated good fit (Xia & Yang, 2018) for the overall goodness-of-fit statistic (RMSEA= = 0.055), for the SRMR (0.60), and for the group-level goodness-of-fit statistic the coefficient of determination (CD = 0.96, not shown in table due to space constraints); other indices suggested less acceptable fit (CFI = 0.87, TLI = 0.83). However, as previously noted, our model included several weak factor loadings, significantly decreasing the validity of CFI and TLI for assessing fit under these conditions (Ximénez et al., 2022).

Victimization at Wave 1 was positively related to victimization at Wave 2. This association was strong (β = .81). Similarly, social support at Wave 1 was positively and moderately associated with social support at Wave 2 (β = .44). The cross-sectional moderate association between victimization and social support was negative, both at Wave 1 and at Wave 2 (β = −.33 and β = −.32, respectively). Following suggested modification indices, the final model included significant correlations between residual terms corresponding to social support indicators across time (rε Significant other W1–W2 = .21, p < .05, rε Family W1–W2 = .42, p < .01, and rε friends W1–W2 = .5, p < .01). See Figure 2 for the final model. As hypothesized, higher levels of victimization at Wave 1 were significantly related to decreases in social support at Wave 2. While significant, this association was weak (β = −.15). However, the association between Wave 1 social support and Wave 2 victimization was not significant. Social support indicators at Wave 1 did not significantly predict social support indicators at Wave 2 (although the social support factor and the residual terms were significantly related), thus those paths were not included in the final model.

5 DISCUSSION

This study examined the bidirectional longitudinal relationship between social support and victimization using longitudinal data of Latino teens. This is an important contribution as it examines social support as a potential mechanism related to victimization, which has been identified as an important gap in the stress-distress-social support research (Uchino & Birmingham, 2011). The longitudinal DAVILA data offered the opportunity to thoroughly test these associations. The first research question examined the relationship between social support at Wave 1 and Latino youth victimization at Wave 2 and was anticipated to show that social support would protect teens from subsequent victimization (stress prevention). We did not find support for this hypothesis. The second research question examined how Latino youth victimization at Wave 1 influenced social support at Wave 2 and was anticipated to show that victimization would be associated with a worsening of social support over time (support deterioration). This hypothesis was supported.

The results from this study indicate that there is a weakening of social support over time after victimization that provides evidence for the support deterioration model. Namely, distress caused by victimization could complicate accessing social support or the perception of social support. Social isolation is often part of the dynamics of partner violence and has been found to especially impact social support from friends (Coohey, 2007). Alternatively, peers could become overwhelmed or feel inadequately prepared to deal with the victimization of their peers, and in turn withdraw support. Similar findings have surfaced with perceived support, number of friends, and connectedness after victimization (Smokowski et al., 2014; Tomlinson et al., 2021; Wallace & Ménard, 2017), such that support decreased over time. For example, forcible rape was associated with lower levels of popularity and centrality in friendship networks among adolescent girls, but importantly, attachment to friends and school, mediated these relationships (Tomlinson et al., 2021). It is also important to mention that secondary trauma could play a role. Social network members may experience trauma symptoms themselves as they learn about the victimization of their network members and/or this could re-trigger their own victimization experiences.

Evidence of social support serving as a stress prevention mechanism (preventing future victimization), was not found as the relationship between Time 1 social support and Time 2 victimization was nonsignificant. Other longitudinal studies did find evidence for the protective effect of social support over time, but these were limited to bullying victimization (Kendrick et al., 2012; Lester et al., 2013), which may account for the difference in findings. We included five different forms of victimization in our model and perhaps some of these are more resistant to the influence of social support. Importantly, in the current study, there were negative and cross-sectional relationships between victimization and social support at each wave. Thus, within a limited time period, social support was moderately protective. These effects could be due to the immediate role of social support—feeling support and thus not engaging with unhealthy partners or risky situations or the ability of peers to name and intercede in potentially violent situations, for example. Relationships with parents and peers may also serve as a guidepost for intimate relationships as far as closeness, mutuality, and respect (Hébert et al., 2019). Other potential mechanisms include that social support could be related to better decision making, proactive coping, increased self-esteem and confidence (Uchino & Birmingham, 2011) which could prevent victimization experiences. The protective effect of social support could also be enhanced by other protective factors, as maternal support and youth's social skills were identified as particularly protective for Latino youth, following different types of victimization (Mariscal, 2020). Youth with higher levels of social skills may be able to express their needs, engage their network, and receive higher levels of social support.

However, whatever promotive value there was in social support, it did not predict victimization 1 year later. Perhaps this reflects a fast-changing social ecology for youth. It is important to note that the association between Wave 1 social support and Wave 2 social support was modest at 0.44. Thus, levels of social support appear to change more rapidly than victimization status, and this may be related to the time-bounded effects of protection from social support. Of course, disclosure to peers, family, or significant others may not actually be supportive given their reactions. For example, in one study those who were revictimized sexually were more likely to tell friends about the victimization than those who were not revictimized and responses to disclosure tended to be more blaming and offer less tangible or emotional support for those revictimized (Mason et al., 2009). Recent work underscores how responses to disclosure affect the future functioning of sexual abuse victims, both in positive and negative ways depending on the quality of the response (e.g., believed the victim or did not believe the victim) (Therriault et al., 2020). Another possibility is that social support may more closely relate to perpetration instead of victimization as indicated in another study that found friend social support to be related to decreased physical and emotional dating violence perpetration, but only emotional dating violence victimization (Richards et al., 2014).

Additional findings show that victimization at Wave 1 was strongly predictive of victimization at Wave 2 (Cuevas et al., 2020). While in line with much of previous work on this issue, it bears repeating that victimization experiences spur a trajectory that includes future victimization. These early victimization experiences could exacerbate risk factors and create a developmental cascade effect leading to additional victimization or a normalization of violence (Finkelhor, 2008; Hébert et al., 2019). One of the most often pointed to potential resources to mitigate this trend (i.e., social support) was found to be unrelated to victimization over time.

There are several limitations to this study including a lack of direct questioning on how social support network members responded to victimization experiences or what social support means to participants. It is important to note that there were significant residual correlations between social support indicators across time. This may suggest that the social support measure potentially did not capture some dimension of social support that is important for participants, which could be further explored in future studies. Further, relationships evolve over time as well as the way in which participants define or perceive support from friends, family, and significant others, among others, which was not explored in this study but may contribute to the social support deterioration identified. We also were not able to investigate the potentially differential influences of social support from peers, family members, and significant others, nor examine gender differences in more detail. Future studies with larger sample sizes could conduct invariance testing for gender and compare Latino youth to other racial/ethnic groups to assess whether there are gender and racial/ethnic differences in the construct of social support. We also examined victimization as a whole, including multiple types of victimizations. Future studies could examine sexual violence or poly-victimization separately, for example. Clearly many constructs relate to victimization over time, and we are modeling only one. For example, the well-being of youth includes not only social support but support from schools, neighborhoods, communities, and cultural strengths, among others. Nonetheless, the examination of multiple forms of victimization and multiple social support sources over time adds to the merit of this study.

There are several implications from this study. First, social support has a protective role cross-sectionally, despite the lack of longitudinal association between social support to victimization. Thus, interventions can seek to bolster social support from family, friends, and significant others so that these time-bounded effects are maximized. This is in line with the Centers Disease Control and Prevention's recommendation to connect youth to caring adults and activities and promote family environments that support healthy development (David-Ferdon et al., 2016). Second, it is important for social supports to know how to respond to victimization experiences. For example, offering non-judgmental support, offering resources for coping with violence, and not blaming the victim, are useful approaches to learn so that social support does not decrease following victimization experiences due to feelings of inadequacy. This is an important intervention point and efforts can be made to educate teens and families about positive supportive responses to victimization while maintaining personal well-being of the helper. Knowing how to respond to violence is an important component of bystander intervention models and indeed, a sense of responsibility and confidence in effective interventions allows youth to respond in positive ways (Debnam & Mauer, 2021). However, more work is needed to equip youth and adults to respond in helpful ways over a long-term period. Another important component is destigmatizing victimization status so that disclosure of victimization does not lead to isolation of victims.

The strengths of this study lie in the understudied sample, a comprehensive measurement of victimization, and longitudinal measurement of victimization and social support. While social support was protective for victimization, this effect was limited to cross-sectional analyses. Over time victimization appears to weaken social support for Latino teens and social support does not confer protective status over time. While social support offers promise for interventions, future studies must also seek to improve the understanding of social support and its protective mechanism over time.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported by Grant Nos. 2009-W9-BX-0001 and 2011-WG-BX-0021 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Findings and conclusions of the research reported here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the US Department of Justice.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in National Archive of Criminal Justice Data at https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/NACJD/studies/34630, reference number https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR34630.v1.