What is in the news today? How media-related affect shapes adolescents' stance towards the EU

Part of this research has been presented at the 26th Workshop of Aggression on the 10th – 12th November in Jena, Germany.

The statistical analysis was preregistered. Analysis scripts and data necessary to reproduce the results can be retrieved from https://osf.io/fcnva/?view_only=a0dfex977f04645ca8a84022a2d8989c6

Abstract

Introduction

Adolescence is regarded as a formative period for political development. One important developmental context is media. Negatively perceived political media content can foster populistic attitudes, which in turn decreases support of political institutions, such as the European Union (EU). As media valence effects are short-lived, this study examined intra-individual associations of media valence with European identity commitment and affect towards the EU, as well as indirect effects via populistic attitudes across 10 days.

Methods

We implemented a 10-day daily diary study with 371 adolescents from Germany (January to February 2022). Adolescents were on average 14.24 years old (SD = 0.55) and 60.4% were female. We estimated the hypothesized associations using multilevel structural equation models and dynamic structural equation models.

Results

We found significant associations between populistic attitudes and negative affect towards the EU on the same day and the next day. The lagged effect became nonsignificant, when including both same day and lagged effects into one model. Populistic attitudes were not significantly associated with European identity commitment within days or across days. Negative media content was associated with higher populistic attitudes on the same day and indirectly associated with negative affect towards the EU (b = −.01, 95% credible interval [−0.010, −0.004]).

Conclusion

Negatively perceived political media content was associated with higher populistic attitudes and more negative affect towards the EU concurrently. Our results imply that media plays an important role for adolescents' development.

1 INTRODUCTION

Adolescence is believed to be a formative period for the development of stable political orientations (Impressionable Years hypothesis, Sears & Levy, 2003), as adolescents reach a stage, in which they are cognitively able to focus on social and political questions, form opinions, and develop a political identity. These political orientations include opinions, behaviors, and so on. for national and supranational politics (e.g., European Union [EU]). Although a strong political identity is generally associated with lower levels of political skepticism and discontent, it is furthermore relevant for adolescents' support for the EU (Weßels, 2007). Considering the general rise of populistic and Eurosceptic attitudes within the EU (Hameleers et al., 2017; Mazzoleni, 2008) and adolescents' susceptibility for populistic messages (Sinczuch et al., 2021), this study aims to contribute to our understanding of political socialization of adolescents through media and how media affects EU support-related outcomes.

Media is a very important social context for adolescents' political socialization and acquisition of political identities (Eckstein, 2019). Adolescents are at the same time active searchers (e.g., deciding to read news), as well as passive consumers (e.g., reception of news on one's time line) and their views on political questions can be influenced by media content and tone of that content (Schuck, 2017). It is argued that consuming media can lead to more political engagement through cognitive mobilization (Norris, 2000), whereas it can also increase general antiestablishment feelings, political disaffection, and alienation (Mazzoleni, 2008).

Media effects are likely short-lived (McKinney & Chattopadhyay, 2007) and need closely spaced observations to be measured adequately, as for example in intensive longitudinal designs (e.g., experience sampling method [ESM] and daily diaries). Previous studies focusing on media effects on outcomes of political socialization have mostly relied on panel and longitudinal designs (e.g., McKinney et al., 2014; de Vreese & Boomgaarden, 2006), thereby overlooking potential day-to-day processes that might eventually lead to changes in attitudes or development over a longer time period. We aim to address this gap by examining these day-to-day processes and shed some light on differences between adolescents in within-person political socialization processes. To do so, we will examine the within-person dynamics among media valence, populistic attitudes, negative affect towards the EU, and European identity commitment in a 10-day daily diary study. This approach allows us to examine fluctuations and systematic couplings in these constructs on a short (day-to-day level) timescale and to capture these constructs closer in time to when they happen in real life.

1.1 Media as socialization context

Individuals develop within social contexts (Bronfenbrenner, 1981). Especially relevant for political development are family, peers, school, or media (Eckstein, 2019; Greenstein, 1965). When developing opinions about the EU and Europe, media is probably one of the main contexts outside school in which adolescents are confronted with the two (Norris, 2000). EU and Europe related topics are rarely relevant for everyday life and also meeting other Europeans can be quite challenging outside vacation times or (social) media. Following agenda-setting theories (McCombs & Valenzuela, 2021), adolescents are to some extent influenced by media's agenda setting independent of whether they consume political content actively or passively; although media cannot determine what and how people think about certain topics, they certainly influence what topics are seen as important and how people feel about those topics (e.g. Cappella & Jamieson, 2010; Schuck, 2017; de Vreese & Boomgaarden, 2006).

In explaining how media affects political development, two paths can be differentiated. The first path is assumed to be a virtuous circle (Norris, 2000), in which media consumption has a positive impact on political knowledge, engagement and trust. The second path is a vicious circle (Spiral of Cynicism hypothesis; Cappella & Jamieson, 2010), in which media consumption fuels political apathy and cynicism. Both paths are assumed to be self-reinforcing, and might be dependent on tonality or valence of reported content (Schuck, 2017). Media valence can have short-term behavioral effects (e.g., on vote choice), but can also negatively affect trust in politicians in the long run (Kleinnijenhuis et al., 2006).

1.2 Media, populism and the EU

Research on adults and adolescents aged 16 and older has shown that negative media valence is positively associated with political orientations, such as political alienation, distrust and populistic attitudes (Cappella & Jamieson, 2010; Galpin & Trenz, 2018; de Vreese, 2007). These are in turn detrimental for the support of political institutions (e.g. EU) and its proxies (e.g. European identity commitment, affect towards the EU) as well.

EU support can be affected by those political orientations in two ways: first, these political orientations tend to extrapolate from lower (national) to higher (EU) order political institutions, as for instance distrust in one's own government extrapolates to distrust towards the EU (Armingeon & Ceka, 2014; Ruelens & Nicaise, 2020). Arguably, populistic attitudes towards one's own government could also increase populistic attitudes towards higher-order political institutions, such as the EU. Second, populism and Euroscepticism tend to coincide in contemporary Europe (Rooduijn & van Kessel, 2019; de Vreese, 2007).

Negative political orientations can affect EU support and proxies of EU support, such as European identity commitment (Weßels, 2007), and affect towards the EU. European identity commitment is not only strongly associated with EU support, but also theorized as being relevant for the long-term stability of positive attitudes towards the EU and European integration (Habermas, 2014; Risse, 2010). Even though European identity commitment tends to be relatively stable and might even act as a buffer against populism (Hameleers et al., 2017; Weßels, 2007), it eventually deteriorates, if populistic attitudes are experienced over a longer period of time (Weßels, 2007). Affect towards the EU is associated with EU support and arguably fluctuates more than European identity commitment. Populistic attitudes likely have an impact on those fluctuations, such that populistic attitudes generate or amplify existing negative emotions, like anger and fear (Nguyen et al., 2022). Those negative emotions are negatively associated with EU support (van Spanje & de Vreese, 2011; Verbalyte & Scheve, 2018).

1.3 The present study

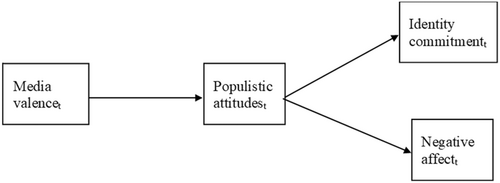

We examine daily effects of media valence on two proxies of EU support, European identity commitment and negative affect towards the EU, mediated by daily populistic attitudes in a sample of adolescents. Specifically, we hypothesize that negative perceived media valence will positively predict populistic attitudes and indirectly negatively predict European identity commitment on the same day and next day at the within-person level. We also hypothesize that negative perceived media valence will positively predict populistic attitudes and indirectly positively predict negative emotions towards the EU on the same day and next day at the within-person level (see Figure 1).

Hence, we predict that on days on which adolescents perceive more negative media valence than they usually do, they will report higher than usual populistic attitudes and in turn, higher negative emotions towards the EU and lower European identity commitment than they usually do. We assume media effects to be mediated by populistic attitudes as negative media valence can foster political alienation and cynicism (Manucci, 2017), thus increase individual's populistic attitudes. Evidence for the assumed associations has been found for adult or late adolescence samples (usually 16 to 25). We want to examine these associations with younger adolescents (age around 14 years), because this group has been found to have developed first political orientations (Torney-Purta, 2002). Furthermore, we want to examine these associations using short-term, intensive longitudinal data. By assessing the constructs of interest daily across 10 consecutive days, we can examine whether there is a systematic coupling between the ups and downs of media use and political attitudes in a random snapshot of adolescents' everyday lives (Bolger et al., 2003). This methodology has rarely been used in studies focusing on media effects on outcomes of political socialization, yet it has potential to further our understanding of political socialization in adolescence and the specific influence of media-related affect.

2 MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study hypotheses and statistical analysis were registered after data collection and partial data access using a template for ESM research (Kirtley et al., 2022) (https://osf.io/huqc9/?view_only=dbaf62b7a6c8490292ee34b5a983fd4d). Prior knowledge of the data can be retrieved from the section “Sampling Plan” and included a qualitative assessment of political content, frequencies of days on which political content was seen, heard or listened to and six random individual trajectory plots for European identity commitment.

2.1 Participants

The present study was part of a larger study (JUROP; www.jurop.uni-jena.de) with n = 1206 (51.7% female, 46.8% male, 1.5% diverse; Mage = 14.39, SDage = 0.02) adolescents that aimed to assess behaviors and attitudes towards EU and Europe, and factors that influenced those. The Study stretched over one school year (2021/2022) and included a longitudinal paper–pencil questionnaire with two measurement points and a daily diary study in between the two measurement points. A random sample of n = 400 out of the total of 1206 adolescents of JUROP was invited to participate in a daily diary study. Out of those, n = 371 adolescents agreed to participate and constitute the sample used for the present analyses. Demographic data was obtained from the longitudinal questionnaire. All other measures reported in the present work were collected in the daily diary part of JUROP. Students who did not have access to an own smartphone could borrow one from the research team. Participants1 were on average 14.24 years old (SD = 0.55) and 60.4% were female (38.8% male, 0.5% diverse). Most students were born in Germany (90.8%) and were enrolled in college-bound high schools (64.2%), vocational schools (7.8%), or comprehensive schools (27.8%).2 The majority of our students were ethnic majority members (72.8%), followed by second-generation immigrants (17.8%) and first-generation immigrants (4.9%, missings = 4.6%).

2.2 Procedure

Participants were recruited via their respective schools (e-mails, telephone, and class visits). Participating students came from two federal states, Thuringia (former Eastern Germany), and North-Rhine-Westphalia (former Western Germany) and visited schools from different academic tracks (college-bound high schools, vocational schools or comprehensive schools). During 10 consecutive school days (first cohort: January 24, 2022, until February 4, 2022; second cohort: January 31, 2022, until February 11, 2022) participants received daily text message invitations on their smartphones to an online questionnaire. The invitations were sent out at 5 p.m. (after school hours) and up to two reminders were sent at 6 and 7 p.m. Participants could answer between 5 p.m. and midnight every day. In every daily questionnaire, participants answered the same 16 questions. The compliance rate was adequate, with 2942 out of 3710 (371 adolescents × 10 days) questionnaires completed, corresponding to a compliance rate of 79.3%.

Before the daily diary study, participants had to complete the paper–pencil questionnaire in which we included demographic information and baseline measures. Participants received a 25€ coupon after starting and another 15€ coupon after completing their questionnaire on a minimum of 8 days as compensation for participating in the daily diary study.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Media valence of political content

Students were asked on each day via an open-ended question what political content they had seen, heard, or read about that they found particularly interesting (“We are interested in content that you have seen, read or listened to in different media [e.g., TV, Instagram, Twitter, news magazines]. Which political content was particularly interesting for you today?”). They then rated this specific content on a five-point Likert scale ranging from −2 (very negative) to 2 (very positive). Valence ratings on days without political content were recoded as zero. A value of zero therefore means either neutral or no political content on a given day. In general, all open answers were considered to be political. To assess, if the task was understood correctly, two research team members screened all open responses consensually and discussed potential unpolitical content. If both team members judged a content as unpolitical (e.g. “Gaming,” “Isaac Newton is reborn,” “Germany's Next Top Model”), it was recoded as not political. This was the case for 16 out of 1428 events (1.1%). Disagreement was resolved by discussion and if it could not be resolved, the initial report by the participants, who reported the event as a political event, was retained (5 out of 1428 events in total: 0.4%).

2.3.2 Populistic attitudes

Daily populistic attitudes were measured with three items adapted from Schulz et al. (2018) (“When I think back to today's political events, then I think that… 1.) politicians have lost contact with their citizenry, 2.) politicians should listen more to their citizenry, 3.) the citizenry should be asked for political decisions”) and one newly created item “4.) Today I was mad at politicians”). We created the fourth item to balance the two dimensions antielitism (Items 1 and 4) and popular sovereignty (Items 2 and 3) from Schulz et al. (2018) scale. All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (do not agree at all) to 5 (fully agree). The within-person internal consistency was estimated as ωwithin = .50 and the internal consistency on the between-level was estimated as ωbetween = .78 (Geldhof et al., 2014).

2.3.3 Negative affect towards the EU

Daily negative affect towards the EU was measured with three items: Anger (German: Wut), fear (Angst), and rejection (Ablehnung). Participants rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (do not agree at all) to 5 (fully agree), to what extent they had felt these emotions towards the EU today. The within-person internal consistency was estimated as ωwithin = .44 and the internal consistency on the between-level was estimated as ωbetween = .87.

2.3.4 European identity commitment

Participants' daily European identity commitment was assessed with a single item from the Utrecht-Management of Identity Commitments Scale daily diary scale (Becht et al., 2016; Klimstra et al., 2010) (“We want to ask you, what your current feelings towards the EU and Europe are. How much do you agree with the following statements? 1.) I feel European”). Participants could rate their level of identification on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (do not agree at all) to 5 (fully agree).

2.4 Data preparation and data analysis

Before our analysis, we checked whether there was a linear time trend in any of the four study variables across the 10 days. This was done to ensure that the stationary assumption of the statistical model was met (see McNeish & Hamaker, 2020). To that end, we conducted multilevel regression models with day as a predictor for media valence, populistic attitudes, European identity commitment, and negative affect towards the EU in Mplus 8.8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017).

For our main analysis, we calculated both multilevel structural equation models (same day effects) and two-level dynamic structural equation models (lagged effects, and same day & lagged effects) (DSEM; McNeish & Hamaker, 2020) separately for both outcomes (negative affect towards the EU and European identity commitment) in Mplus 8.8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017). Both types of modeling allow accounting for the nested data structure with daily assessments on Level 1 nested within adolescents on Level 2.3 Models included (1) same-day effects models, (2) lagged effects models, (3) same-day and lagged effects models, and (4) same day mediation models. In all models, we began with a model assuming fixed effects of time-varying predictors only, then included random effects for regression coefficients, and then added random residual variances (location-scale models). Including random effects for regression means that effect sizes can vary across participants, that is, adolescents vary in strength and direction of the assumed associations. Location-scale models allow the residual variances to differ across participants, meaning that we can account for differences in within-person variability across participants (McNeish & Hamaker, 2020). Between-person variation in residual variances indicates that the amount of day-to-day fluctuation in the variables that is not explained by all predictors in the model differs between adolescents.

The hypothesized associations were only modeled on the within-level. On the between level, we estimated fully saturated models, meaning that random intercepts and random slopes were estimated as being correlated without specifying any direction of the associations. In case of convergence issues, we dropped the correlations among random slopes from the model. We only tested for mediation, if significant associations between mediator (populistic attitudes) and outcome (negative affect towards the EU, European identity commitment) were found. For a description of all estimated models, please see the Supporting Information: Material A.

We estimated all models using the Bayesian estimator in Mplus with two Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains and a burn-in period of 50%. The use of Bayesian MCMC is required, because DSEM are sufficiently complex that traditional frequentist estimators like maximum likelihood often encounter convergence issues or are intractable (Muthén & Asparouhov, 2012). We started with 2000 iterations keeping only every 5th iteration (thinning factor = 5) (for more detailed explanation on the model specifications and Bayesian estimation in Mplus, please see Hamaker et al., 2018).

If the model did not successfully converge, we gradually increased thinning factor or the number of iterations. To check for local solutions, we doubled the number of iterations per model and compared the results of the two models. If the two models differed, we doubled again. Convergence was inspected by using the Potential Scale Reduction Factor (<1.1) and by inspecting Bayesian parameter trace plots and autocorrelation plots. Parameters whose 95% credible interval did not cover zero were interpreted as statistically significantly different from zero. For the Mplus syntaxes of our models, please see Supporting Information: Material B.

2.5 Missing data

To account for unequal time intervals and design-based missingness (no measurements on weekend days), days were coded with respect to their actual differences (i.e., the first Friday is coded as Day 5, the second Monday as Day 8). Design based and other missing data were estimated by a Kalman filter approach, as implemented per default in Mplus (see Hamaker & Grasman, 2012). Broadly speaking, the Kalman filter makes a prediction of the next observation based on all information available up to the current observation. The prediction is compared with the actual observation and updated. If there is no observation, the Kalman filter continues with the prediction it had for the next observation and updates it with the next observation.

3 RESULTS

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for and within-correlations among media valence, populistic attitudes, European identity commitment, and negative affect towards the EU. Intraclass correlations (ICC) were high, except for media valence, meaning that populistic attitudes, European identity commitment and negative affect towards the EU were highly correlated from day-to-day within participants.

| n | Media valence | Populistic attitudes | European identity commitment | Negative affect towards the EU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 371 | −0.21 (SDwithin = 0.79, SDbetween = 0.45) | 3.31 (SDwithin = 0.38, SDbetween = 0.55) | 3.73 (SDwithin = 0.48, SDbetween = 0.74) | 2.30 (SDwithin = 0.39, SDbetween = 0.67) | |

| Correlations | |||||

| Populistic attitudes | −0.13 | ||||

| European identity commitment | −0.03 | 0.04 | |||

| Negative affect towards the EU | −0.07 | 0.12 | −0.04 | ||

| ICC | .24 | .68 | .70 | .75 |

- Note: Within-person correlations among the variables are reported. The first row depicts sample means of person means (SD are provided in parentheses). Scale for media valence: −2 (very negative) to 2 (very positive), scale for others: 1 (fully disagree) to 5 (fully agree). Means were calculated on the basis of person means per variable. Within-person correlations for the variables are given (ICC).

- Abbreviations: EU, European Union; ICC, intraclass correlation.

3.1 Confirmatory analysis

Multilevel regressions with study day as predictor of media valence, populistic attitudes, European identity commitment and negative affect towards the EU yielded no significant linear time trends (R2 < 1% for all).

Next, we tested whether populistic attitudes on the previous day or same day is associated with European identity commitment or negative affect towards the EU. If the association between populistic attitudes (t or t − 1) and an outcome (t) was significant, we calculated a same day mediation model for that outcome. Regarding same day effects, the most complex and still converging model was a random effects models with a random slope. European identity commitment was not associated with populistic attitudes on the same day (b = .03, 95% credible interval, 95% CI [−0.03, 0.09], R2 = .05), but negative affect towards the EU was significantly positively associated with populistic attitudes on the same day (b = 0.13, 95% CI [0.07, 0.18], R2 = .06). Participants showed higher negative affect towards the EU on days when they reported higher populistic attitudes (see Table 2).

| European identity commitment | Negative affect towards the EU | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Posterior median | 95% credible interval | Posterior median | 95% credible interval |

| Fixed effect | ||||

| pop. att. t → outcome t | 0.03 (0.02) | [−0.03, 0.09] (−0.02, 0.07) | 0.13a(0.11a) | [0.07, 0.18] (0.07, 0.15) |

| Random variance | ||||

| pop. att. t → outcome t | 0.09 | [0.05, 0.14] | 0.06 | [0.04, 0.10] |

| Res. Var. | 0.22 | [0.21, 0.24] | 0.14 | [0.14, 0.15] |

- Note: Table depicts unstandardized coefficients (standardized coefficients in parentheses).

- Abbreviations: EU, European Union; pop. att., populistic attitudes; Res. Var., residual variance.

- a Non-null credible interval.

Regarding lagged effects, the most complex and still converging model was a random effects model with (four) random slopes. All autoregressive effects were significant. European identity commitment on t − 1 was significantly and positively associated with European identity commitment on Day t (b = .31, 95% CI [0.24, 0.38]). We found similar autoregressive effects for negative affect towards the EU (b = .33, 95% CI [0.26, 0.40]) and populistic attitudes (Europ. comm. model: b = .32, 95% CI [0.26, 0.39], negative affect model: b = .35, 95% CI [0.28, 0.41]).

Populistic attitudes on t − 1 were not associated with European identity commitment on t (b = .07, 95% CI [−0.02, 0.15]). However, European identity commitment on t − 1 was significantly associated with populistic attitudes on t (b = −.05, 95% CI [−0.102; −0.004]). Higher European identity commitment on the previous day was associated with lower populistic attitudes on the current day. Populistic attitudes on t − 1 were significantly positively associated with negative affect towards the EU on t (b = .08, 95% CI [0.01, 0.16]). Higher populistic attitudes on the previous day were associated with higher negative affect towards the EU on the current day. No cross-lagged effect of negative affect towards the EU on populistic attitudes was found (see Table 3).

| European Identity commitment | Negative affects towards the EU | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Posterior median | 95% credible interval | Posterior median | 95% credible interval |

| Fixed effects | ||||

| outcome t − 1 → outcome t | 0.31a (0.30a) | [0.24, 0.38] (0.24, 0.35) | 0.33a (0.32a) | [0.26, 0.40] (0.27, 0.38) |

| pop. att. t − 1 → outcome t | 0.07 (0.04) | [−0.02, 0.15] (−0.01, 0.09) | 0.08a (0.08a) | [0.01, 0.16] (0.03, 0.13) |

| pop. att. t − 1 → pop. att. t | 0.32a (0.32a) | [0.26, 0.39] (0.27, 0.37) | 0.35a (0.34a) | [0.28, 0.41] (0.28, 0.39) |

| outcome t − 1 → pop. att. t | −0.05a (−0.06) | [−0.10, −0.00]b (−0.11, 0.01) | 0.01 (0.02) | [−0.04, 0.06] (−0.03, 0.07) |

| Random variances | ||||

| outcome t − 1 → outcome t | 0.14 | [0.11, 0.18] | 0.10 | [0.07, 0.14] |

| pop. att. t − 1 → outcome t | 0.19 | [0.12, 0.27] | 0.16 | [0.11, 0.23] |

| pop. att. t − 1 → pop. att. t | 0.10 | [0.07, 0.14] | 0.11 | [0.08, 0.15] |

| outcome t − 1 → pop. att | 0.04 | [0.02, 0.07] | 0.04 | [0.01, 0.07] |

| Res. Var. | 0.19 | [0.18, 0.20] | 0.13 | [0.12, 0.14] |

- Note: Table depicts unstandardized coefficients (standardized coefficients in parentheses).

- Abbreviations: EU, European Union; pop. att., populistic attitudes; Res. Var., residual variance.

- a Non-null credible interval. Standardized effects in brackets.

- b Interval does not cover zero, as it is on a later decimal negative.

The combined model including same day and lagged effects showed similar results as described above. The only difference was that populistic attitudes on t − 1 were no longer significantly associated with negative affect towards the EU on t (b = −.03, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.10]), after controlling for populistic attitudes on t. As the models indicated only an association between populistic attitudes and negative affect towards the EU, we estimated the mediation model for negative affect towards the EU only.

3.1.1 Mediation model

After establishing an association between populistic attitudes and negative affect towards the EU on the within-level on the same day, we tested our mediation hypothesis. The most complex still converging model was a fixed effect model. Media valence was significantly associated with populistic attitudes on the same day (b = −.06, 95% CI [−0.08, −0.04]). Negative media content was associated with higher populistic attitudes on the same day. Media valence also had a significant direct association with negative affect towards the EU (b = −.03, 95% [−0.05, −0.01]). We found a significant indirect effect of media valence on negative affect towards the EU mediated by populistic attitudes (b = −.01, 95% CI [−0.010, −0.004]) (see Table 4). The proportion of the indirect to total effect was 21.9%. Negatively perceived political media content was associated with higher populistic attitudes and more negative affect towards the EU.

| Negative affect towards the EU | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Posterior Median | 95% credible interval |

| Fixed effects | ||

| med. val. → pop. att. | −0.06a (−0.13a) | [−0.08, −0.04] (−0.17, −0.09) |

| pop. att → neg. aff. | 0.11a (0.11a) | [0.07, 0.15] (0.07, 0.15) |

| med. val. → neg. aff. | −0.03a (−0.05a) | [−0.05; −0.01] (−0.10, −0.01) |

| Indirect effect | −0.01a | [−0.01, −0.00]b |

| Proportion indirect to total effect | 21.9% | |

- Note: Table depicts unstandardized coefficients (standardized coefficients in parentheses).

- Abbreviations: EU, European Unions; med. val., media valence; neg. aff., negative affect towards the EU; pop. att., populistic attitude.

- a Non-null credible interval.

- b Interval does not cover zero, but is on a later decimal negative.

3.2 Sensitivity analysis

Excluding participants that have seen, read or heard political content on three or fewer days (nexcluced = 57) did not change our results for the same day or the mediation model. However, the results changed slightly for the lagged effect and the combined model (same-day & lagged-day effect), insofar as that the lagged effect of European identity commitment on populistic attitudes became nonsignificant.

To investigate possible differential effects of positive or negative media, we conducted an exploratory mediation model with media valence split in two contrasts. For contrast variable 1, we dichotomized perceived media valence in negative political content (−1) versus positive/neutral or no political content (0). For contrast variable 2, we dichotomized perceived media valence in positive political content (1) versus negative/neutral or no political content. We wanted to assess in a more detailed manner, whether seeing negative media content (vs. neutral or no political media content) would have different effects on, for example, populistic attitudes than seeing positive content (vs. neutral or no political media content). Although perceived negative media content instead of other media content was significantly associated with populistic attitudes and negative affect towards the EU (directly and mediated), perceived positive media content instead of other media content was not associated with populistic attitudes or negative affect towards the EU (directly or mediated). All results of the sensitivity analysis can be found in Supporting Information: Material A. In addition, exploratory, preregistered analyses examining between-person differences in within-person effects are also reported in Supporting Information: Material A.

4 DISCUSSION

In this study, we implemented a 10-day daily diary design, in which we examined the effects of media valence on negative affect towards the EU and European identity commitment, and tested whether this effect is mediated by populistic attitudes. With this study we add to our understanding of political socialization in adolescence focusing on the effect of media. The assumed associations were closely assessed to when they happened in real life, allowing for a more accurate assessment of the within-person dynamics. It offers a more fine-grained understanding of the interplay of media valence, populistic attitudes and two proxies of EU support on day to day basis.

Our results are in line with the idea that media valence is associated with affect towards the EU mediated by populistic attitudes. Seeing, reading, or listening to negatively framed political content seems to be associated with higher populistic attitudes and more negative affect towards the EU on the same day. Results for same day associations of populistic attitudes and negative affect towards the EU were robust, yet the lagged association (stronger populistic attitudes today predicting tomorrow's negative affect towards the EU) was no longer meaningful after controlling for the same day effect. This suggests that populistic attitudes have only negative implications for negative affect, if they linger on until the next day. This emphasizes the importance to target dynamic within-person effects on different time scales to fully understand how they unfold across time.

Contrary to our expectations, we could not confirm our hypothesis that negative media valence is indirectly associated with European identity commitment by populistic attitudes. Populistic attitudes were neither significantly associated with European identity commitment on the next day nor on the same day. One reason could be that adolescents might see being European as something different than being a member of the EU, for example having European ancestry, and therefore their European identity commitment might remain unaffected by negative media that aim towards political institutions. Bruter (2003) showed that civic and cultural components of European identity are differently affected by positive and negative news, not in direction but strength of association. A civic European identity was more strongly affected by negative news than a cultural European identity. Committing to a European identity might be important for long-term stability of positive attitudes towards the EU and European integration (Habermas, 2014; Risse, 2010), but only if it includes a political definition of being European (e.g., being member of the EU).

Another reason could be that European identity commitment did not vary as extensively from day to day, as was indicated by relatively large ICCs. Other studies that implemented daily diary assessments for identity processes found fluctuations on identity commitment also on a day to day level, though the size of fluctuations differed across identity domains (e.g., educational vs. interpersonal; Becht et al., 2021; Klimstra et al., 2010). It could be that political identities are relatively stable and unaffected by daily influences, but they might change if populistic attitudes cumulate over a longer period of time (Weßels, 2007). Our results provide relevant information as they aid in locating the appropriate timescale across which European identity processes in adolescents might develop. Future studies could implement a longer observation window to potentially increase the amount of within-person fluctuation in European identity commitment.

Considering the significant cross-lagged negative association between today's European identity commitment with tomorrow's populistic attitudes, it could also be that European identity commitments are protective against populistic attitudes and, even more, decrease populistic attitudes. This finding would be in line with a “buffering-hypothesis” (Weßels, 2007). However, as the buffering effect disappears after excluding low responders (three or fewer days), this not hypothesized finding has to be interpreted with particular caution.

Overall, our results imply that media valence is linked to adolescents' political development. Study hypotheses and data analyses reported in this work were registered after data collection and partial data access. In line with others scholars (van den Akker & Bakker, 2021; van den Akker & Weston, Campbell, et al., 2021), we consider this “postregistration” an important feature to increase transparency and openness in science in cases when more “traditional” preregistration before the start of data collection is not feasible (as is the case in many large-scale projects). One limitation of our study is that we did not differentiate between neutral and no content. According to the assumption of a virtuous media cycle (Norris, 2000), neutral content has likely positive effects on political engagement and knowledge, thereby being negatively associated with populistic attitudes. Not perceiving any content, however, should not be associated with populistic attitudes. Including days of participants on which no political content was perceived might decrease the effects between media, populistic attitudes, and the outcomes, which could explain our nonsignificant findings for lagged media effects on populistic attitudes and European identity commitment. Judging from our sample's amount of days without political content, we would assume politics is not necessarily part of adolescent's everyday life or at least news consumption; nevertheless, they are affected by media in their political socialization, when they encounter content. We note, although, that students are not just passive receivers of news, but also active agents in searching for information. Future studies could therefore implement an experimental design in daily diary studies, in which positive, negative, or neutral political content is given for each participant on each day. This would help to clarify the causal links among media use and political attitudes. Furthermore, future studies might also consider including passive mobile-sensing methods to obtain a more objective measure of adolescents' actual (political) media consumption.

Our study focussed only on stable within-student processes; however, there might be differences on the between-participant level that influence the found associations. An interesting group comparison could be to compare politically engaged vs. not engaged participants. Research with older age groups suggests that highly politically engaged persons are likely less affected by media valence than those who are uninterested in politics and do not actively engage in searching for political content (de Vreese, 2007). Those that search for political content versus those that view it accidental or as part of entertainment might differ as well (Katz et al., 1974). Including measures that assess the frequency of political content perceived per day might be an option. In addition, including interindividual differences such as political orientation might be an interesting direction. Including covariates and specifying associations at the between-person level would certainly add to our understanding of political socialization, but would require a larger sample size either by increasing number of participants or measured days.

5 CONCLUSION

Adolescence is a formative period for the development of political orientations. The present study shows that perceived negative political content is associated with higher populistic attitudes on the same day, which in turn is linked to higher negative affect towards the EU. A similar association could not be found for European identity commitment. Overall, our results suggest that media can influence adolescent's political socialization, especially when media report negatively about political content. Educating adolescents in their media literacy and help them reflect on tone of media and how it affects them could be useful in reducing populistic attitudes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research received funding from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF; Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung; grant numbers 01UG2103A and 01UG2103B). We thank our project partners Peter Noack, Katharina Eckstein, and Astrid Körner, from the University of Jena, for collecting data in Thuringia, which were used for this study. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This research was approved by the ethics committees of the University of Duisburg-Essen and of the University of Jena (FSV 21/047).

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Analysis scripts and data necessary to reproduce the results can be retrieved from https://osf.io/fcnva/?view_only=a0dfe977f04645ca8a84022a2d8989c6.

REFERENCES

- 1 Students of the complete sample were on average 14.39 years old (SD = 0.64) and 51.7% identified as female (46.8% male, 1.5% divers). Most students were born in Germany (86.4%) and were enrolled in college-bound high schools (58.3%), vocational schools (16.9%), and comprehensive schools (25.4%). The majority of our students were ethnic majority members (75.5%), followed by second-generation immigrants (17.6%) and first-generation immigrants (6.7%).

- 2 School types in Germany include college-bound tracks (e.g., college-bound high school), vocational tracks (e.g., vocational schools), or schools combining vocational and college-bound tracks (e.g., comprehensive school). The first school type ranges from Grade 5 to 12 (13 in some federal states), whereas the other two range from Grade 5 to 10 (with variations between federal states).

- 3 DSEM is currently restricted to two-level models and, therefore, we did not add adolescent's classes or schools as an additional level of nesting. Notably, intraclass correlations of our variables on both the class-level and the school-level were overall low (estimates between 0.00 and 0.07), suggesting that there is only limited information on the class or school level in the data collected.