A sweet burden? The effect of bride prices on parents' health

Abstract

The bride price, as an informal institution originated from traditional culture, is pervasive in many areas of the developing world in a form of a payment from the family of the groom to that of the bride at marriage. We study the effects of bride price on parents' health in China. Using information on bride price payment and various health measures from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, we find that the bride price significantly reduces self-reported health among the grooms' parents after addressing the endogeneity issue with average sex ratio within a family computed as an instrumental variable. The reductions are heterogenous across urban and rural areas. Mechanism analysis suggests the negative health outcomes are driven by family debt, heavier psychological stress and longer work hours caused by bride price payments.

1 INTRODUCTION

Marriages are associated with the distribution of property within and across families in most societies. Of various forms of marriage transfers, the bride price is one of the most pervasive in many areas of the developing world (Anderson, 2007; Cherlin & Chamratrithirong, 1988). The institution of bride price specifies that the husband must provide a substantial amount of money or property to the bride's family before they can be married. The payments can be substantial enough to have impacts on the welfare of the couple and their natal families, thus generating significant social and economic discussions.

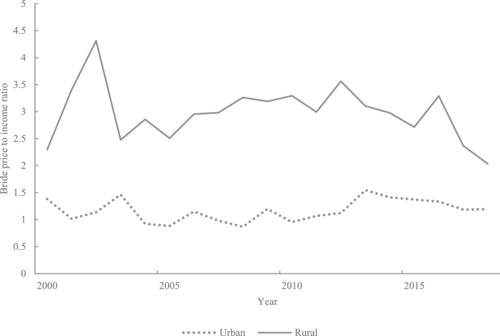

In this paper, we investigate the effect of bride price payment on parents' health outcomes in China. The practice of bride price has been one of the most important marriage customs since ancient China. In recent years, the bride price exceeds the average annual income among urban populations, with the amount reaching three times the average income level in rural areas (Figure 1). Thus, the payment of the bride price is expected to generate a sharp decline in wealth of the groom's family, which can be linked to deterioration of health conditions (Fichera & Gathergood, 2016; Michaud & Van Soest, 2008; Schwandt, 2018). This study aims at uncovering the causal effect of the bride price on parents' health. We further try to identify possible channels through which the marriage transfers cause the observed change in parents' health status.

Using data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), we analyze the causal effect of the bride price on parents' health with an instrumental variable approach. Endogeneity arises for two reasons. First, reverse causality presents because health also affects income generation, which makes the bride price more affordable among healthier parents. Second, omitted variable bias is a concern as we do not observe factors that would simultaneously affect the bride price and parents' health. To address these potential threats in identification, we use the average of sex ratios of marriageable age for corresponding individual grooms within a family located in a city as instrumental variable. The sex ratio is a measure of gender imbalance in the marriage market, which is positively correlated with the amount of the bride price while has no direct impact on health. Results from the control function estimation show a decrease in self-reported health status caused by higher bride price. Higher bride price expenditures are found to decrease the capabilities of completing both activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) among the grooms' parents. Heterogeneity analysis suggests the impacts are different across urban areas and rural areas.

We further examine the possible mechanisms through which the bride price expenditure can affect parents' health. First, parents who cannot afford the bride price may resort to borrowing to finance the payment (Saha, 2017). The financial stress caused by increased debts is associated with declines in self-reported health and physical functions (Drentea & Lavrakas, 2000). In addition, parents will get stressed if their sons are overage singlehood in the Chinese Confucian context (Chen & Tong, 2021). The high bride price, which parents have to prepare for their sons to compete in the marriage market, aggravates their psychological pressure. Along this line, we find paying higher bride price increases parental depression. Third, parents who face higher bride prices may resort to excessive work to earn more money, which may result in worse health outcomes. Our empirical findings also support this channel.

This study makes several contributions to the existing literature. First, while classical literature has extensively discussed the impacts of family income shocks on outcome variables such as consumption (Kazianga & Udry, 2006), risk management behavior (Lybbert et al., 2004), and labor market participation (Kochar, 1995), these income shocks typically occur outside of a family unexpectedly. In contrast, our study focuses on a unique phenomenon where income shocks occur within a family and can be expected. It also emphasizes the role that marriage transfers play in household wealth dynamics among Chinese households, highlighting an important area for future research on household finance in the Chinese context. Second, our study contributes to the literature on intergenerational wealth transmission, which typically involves the transfer of wealth from parents to their offspring. However, in the context of bride price, a significant amount of money is given to a nonfamily member during the parents' lifetime. Furthermore, this study identifies a specific form of intergenerational exploitation where younger generations can jeopardize the well-being of their predecessors through marriage pricing. This contrasts with past literature that has primarily focused on intergenerational exploitation in the reverse direction. Lastly, this study documents the enduring impact of gender imbalance on parental health outcomes through marriage pricing. By investigating the causal impact of bride price on parental health, this study extends current knowledge of marriage transfers to an understudied aspect in the domain of health economics. Additionally, insights into the mechanisms behind these impacts, particularly through the lens of labor market participation, are provided.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. The second section introduces the background and previous literature on bride price in China. Section 3 presents empirical methods and describes the data source, including a discussion of endogeneity. In Section 4, we show results and robustness checks and explore heterogeneity and possible mechanisms. The last section summarizes our findings, provides policy implications, and discusses future study.

2 BACKGROUND

In this section, we describe the background on the bride price in China and review related literature investigating the impact of the bride price and research on the determinants of elderly health status.

2.1 The bride price in China

Payment at the time of marriage existed across different cultures at different times. Among 1167 preindustrial societies investigated by Murdock (1967), marriage payments existed in two-thirds of these regions. Marriage transfers still present widely in developing countries in East Asia, Southeast Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa, such as: China, Thailand, Indonesia, Zambia, Uganda, and so on (Anderson, 2007; Ashraf et al., 2020; Cherlin & Chamratrithirong, 1988; Corno et al., 2020; Goody & Tambiah, 1973). Overall, this marriage market institution is more likely to emerge in areas where polygamy has historically or currently existed (Grossbard, 1978; Tertilt, 2005). Depending on the direction of payment, such transfers can be categorized into bride price, which is the transfer from the groom's family to that of the bride's, and dowry, referring to the transfer from the bride's side to the groom's side. In the traditional patrilineal societies, women usually live with the groom's family after marriage. In exchange for the bride's right to participate in labor and reproduce, the groom needs to pay a certain amount of money to the bride's parents as compensation for raising her and investing in her human capital (Freedman, 1966; Zhang & Chan, 1999). For the right to cultivate part of the bride's family's land, grooms in rural areas may pay more than in urban areas (Cherlin & Chamratrithirong, 1988).

In China, the custom of bride price can be traced back to the Western Zhou Dynasty (Jiang & Sánchez-Barricarte, 2012). It is a wedding etiquette in which the groom presents property to the bride when they get married. However, with evolving economic circumstances, the bride price changed from a symbolic etiquette to a currency transfer in the marriage market. After enactment of the reform and opening-up policy, the amount of bride price continued to rise, and the practice of marriage transfers intensified (Zhang, 2000). In rural areas with substantial female outflow and unbalanced gender ratio, people incur higher bride price expenditures in the marriage market than urban population (Meng & Zhao, 2019). It is also documented that the amount of bride price is relatively constant across families of different income levels in rural China (Zhang, 2000).

2.2 The impacts of the bride price

Studies have been focused on the impact of betrothal gifts on women's welfare. Becker (1981) argues that if women with appropriate human capital accumulation can obtain a sufficiently high capital price in the marriage market, the presence of bride price would induce parents to make better human capital investment in their daughters. Ashraf et al. (2020) focus on the school attendance of girls in different regions of Indonesia, and found that the better women are educated, the more betrothal gifts they receive. Women in areas where the bride price is more prevalent tend to be better educated than those in other areas. However, bride price is also linked to adverse effects on women's welfare. Corno et al. (2020) find that when parents experienced negative income shock induced by bad weather, they tended to let their daughters marry earlier to smooth consumption. Villages with higher average amounts of betrothal payment were more likely to have child marriages. In traditional Chinese society, parents of poor families would force their daughters to marry early to fund their son's bride price, or even sell their daughters as slaves for money (Engel, 1984). Wendo (2004) points out that in sub-Saharan Africa, women are traded as “commodities.” They have no right to reject polygamy, and they are more vulnerable to reproductive diseases. Women who want to divorce may suffer resistance from their parents for fear of not being able to return the bride price. Meanwhile, Lowes and Nunn (2017) confirm that the requirement to return betrothal gifts upon divorce would reduce the wife's happiness.

For parents, marriage payments pose a threat to their retirement decision. Chen and Tong (2021) point out that under traditional ideology, helping children get married and establish a new family is regarded as the obligation and responsibility of parents. If a son remains single for years, parents will be under enormous social pressure and at a higher risk of depression. The groom's parents usually bear most of the wedding expenses, including the bride price, wedding ceremony, and so on. While parents can derive moral satisfaction from their selfless giving and contribution to their children (Hoffman et al., 1978), the economic pressure of marriage payments may force them to reduce consumption or increase labor supply (Bai et al., 2022), even engage in high-risk, high-intensity, long-hour jobs and take on debt. These financial pressures on parents will not be relieved until the son gets married (Tao et al., 2021). However, driven by egoism, some brides and grooms disregard filial. They not only collude to demand high-value betrothal gifts from the grooms' parents when they marry, making the bride price a means of intergenerational exploitation, but also intend to avoid paying debts owed by parents for marriage payments, which seriously endangers the parents' retirement and livelihood (Yan, 2003).

The bride price is associated with negative externalities. High bride prices crowd out parents' consumption and lead to chronic poverty. With rising bride prices, families with sons will lower consumption to increase savings for bride price to increase competitiveness of their son in the marriage market (Du & Wei, 2013; Wei & Zhang, 2011a). In addition, Brown et al. (2011) find that as status competition intensifies, families of poor grooms spend more on weddings, which traps families into chronic poverty. It is also found that high bride price drives criminal activities such as women trafficking and theft of betrothal gifts (Cameron et al., 2019; Hudson & Den Boer, 2004; Jiang & Sánchez-Barricarte, 2012).

2.3 The factors affecting parents' health

Extensive research has been conducted on the factors affecting the health of middle-aged and elderly people. Individual characteristics including age, gender, marital status, illness, lifestyle, education, income, can be important determinants of health status in older age. Most scholars agreed that older women are more likely to suffer from poorer health than older men (Andersen-Ranberg et al., 1999; Yu et al., 1989). Although physical function gradually deteriorates with age (Krause & Jay, 1994), Ferraro (1980) and Cheng et al. (2007) show that the elderly have a higher self-evaluation of their health status than the middle-aged. Tosi and van den Broek (2020) focus on the data from the United Kingdom Household Longitudinal Study and find that the divorce behavior of the elderly can cause fluctuations in their mental health. Galenkamp et al. (2013) claim that self-reported health is associated with chronic disease and physical functioning and state that people with chronic diseases and declined function are prone to have poor self-reported health. Marmot (2002) considers that income level determines material living conditions and social participation and believes that it has a close causal relationship with health status. Cutler and Lleras-Muney (2010) use UK and US datasets and shows that educated people had healthier lifestyles (no smoking, no alcohol, etc.) and safer living conditions. Based on CHARLS data, Liao et al. (2020) find that Internet use can promote mental health and reduce the risk of depression among the elderly.

There is also evidence that children's behavioral characteristics also affect parents' health status. Yahirun et al. (2017) study the relationship between children's education and parents' mid- and long-term health and finds that children's education can prolong parents' lifespan and reduce their mortality in the long run. Ma (2019) explores the causal effects of children's education on various health indicators of parents. The results show that children's years of education are associated with higher self-reported health score, better cognitive function, and improved depression symptoms among parents. Teerawichitchainan et al. (2015) use data from Southeast Asian countries and find that parents living with their children could effectively improve their mental health. Böhme et al. (2015) analyze the effect of children's migration on parents' self-reported health, body mass index, and other health indicators. Their results suggest that children's international migration could increase financial support for parents and make them improve their diet, thus improving parents' health.

3 METHODS AND DATA

3.1 Empirical model

The above empirical model is subject to endogeneity concerns for two reasons. First, there may be omitted variable bias although we control for many observable confounding factors. The amount of the bride price is affected by local economic condition, customs, social ethos, gender imbalance, and other factors, which are difficult to measure and are not reflected in the model. In addition, the economic income and wealth status of the family are also important factors that affect the amount of the bride price. We do not observe family income and wealth at the time of sons' marriage, which will also lead to omitted variable bias. Second, there is also the threat of reverse causation. Healthy parents may have a higher ability to accumulate wealth, so they can pay for a higher level of the bride price. On the contrary, parents who are sick and weak may bear long-term medical expenses and cannot afford the high cost of betrothal gifts.

To address the endogeneity concerns, we employ an instrumental variable approach exploiting the average sex ratio computed by taking average of the city-cohort level sex ratio faced by each specific individual son within a family. For instance, considering a family consisting of two sons born in 1980 and 1985, respectively, given that husbands are typically older than their wives, the sex ratio of the marriageable age cohort faced by the older son would pertain to those born between 1980 and 1983. While for the younger son, it would be for those born between 1985 and 1988. We also check the robustness with assumption that the wives are 5 years younger than husbands. Then we average the two ratios. Under this configuration, the potential identification hypothesis is situated within variations in sex ratios among families. On the one hand, the rising bride price in recent years is highly correlated with the sex imbalance in the marriage market. Due to the strict family planning policy and the outflow of women, the gender ratio has been obviously imbalanced, leading to increased pressure on men to find a mate, while women's marital bargaining power has been improved (Bélanger & Tran Giang Linh, 2011; Wei & Zhang, 2011b). When there are too many men relative to women, they have to pay more betrothal gifts to compete for scarce women (Becker, 1981). This implies that as the sex ratio rises, the more bride price will be paid accordingly (Francis, 2011). In the regression analysis, the sex ratio is similar to the “operational sex ratio” in biology, defined as the proportion of sexually competitive males to females that are about to mate (Cameron et al., 2019). Since the average and median marriage time of all children in the sample is approximately in 2001, we adopt the 2000 population census to calculate the ratio of men to women in each city. On the other hand, the sex ratio reflects the overall relative proportion of men to women at the family level, which is not directly associated with the health status of individual respondent, meeting the requirements for the instrumental variable. Therefore, it is reasonable to use sex ratio as the instrumental variable of bride price.

We adopt a control function method and obtain a two-step estimator that exploits the partially linear structure of the model. The first step consists of estimation of the residuals of the first stage regression where the endogenous bride price is regressed on the sex ratio as well as a full set of control variables. The second step is the estimation of Equation (1) with the first-stage residual included as an additional explanatory variable. Given the ordered categorical dependent variable, we employ the ordered logit regression in our second step.

3.2 CHARLS data

We use data from the CHARLS. The database collects high-quality micro-data on the family and personal information of middle-aged and elderly people aged 45 and above in China. Information collected in the survey includes demographic characteristics, employment and pension, household income and expenditure, evaluation of health function, healthcare utilization, and insurance participation. CHARLS interviewed a stratified random sample of population in 28 provinces, 150 counties, and 450 communities or villages. Households are tracked every 2–3 years from the baseline survey in 2011. We use information from the latest wave of the survey in 2018. We restrict the sample to individuals aged between 45 and 85. We further exclude samples where there is no son in the family. Observations with missing information on our key variables are dropped. Our sample finally includes cross-section information on 12,842 individuals.

We observe bride price expenditures at the household level. For households with multiple sons, there are multiple records of bride price payments made for each son. CHARLS has detailed information about the year each son got married, the expenses related to betrothal gifts, and the cost of housing. Since the wedding house is also a form of the betrothal gift, and usually takes up a large proportion of the marriage payment, it is incorporated into the calculation of bride price. Since the year of marriage can be different from the year of interview, we account for inflation in the bride price expenditures by standardizing expenditures at the price level of 2018 according to the provincial CPI index. If the sons in the family are young and unmarried, the amount of bride price borne by parents is deemed to be 0. Since we are interested in household level expenditures in bride price, we use the sum of the adjusted bride price paid for all sons in the family as our independent variable.

Our key outcome variable is the health status of the parents. In accordance with previous literature, we use self-reported health score as the indicator of health status (Giles & Mu, 2007; Huang et al., 2016). Self-reported health reflects the individual's comprehensive evaluation of his body conditions. We extract this information from responses to the CHARLS survey question “Would you say your health is very good, good, fair, poor or very poor?” The responses range from a 1 to 5 scale with 1: very poor; 2: poor; 3: fair; 3: good; 5: very good. Higher health score corresponds to better health status.

We control for predetermined variables that are likely to impact parents' health. They are classified into three categories–individual characters, household characteristics, and city fixed effects. Rich demographic information is available in CHARLS. We control for individual demographic characteristics such as age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, and education of the respondent and children. Hukou status indicating residency in urban or rural areas is also added to the model to account for systematic differences in the medical system. We are also able to incorporate other individual characteristics that directly link to health status, which include variables such as drinking or smoking in the past year. Household level characteristics are annual household income2 and the number of children, and we are concerned about whether the respondents live with their children. More importantly, we control for dowry expenditure to isolate the health effect of specific marriage transfers of bride price. Similarly, if all the daughters are not married, or there is no daughter in the family, the amount of dowry is considered to be 0. To control for the differences in economic development and geographic environment across different cities, we include city dummies in the regressions.

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics of each variable. The sample consists of 12,842 respondents, of whom 45% are male. The average self-reported health score is 2.969, which stands for a fair health status. The average age is 65.8 years old. 82.5% are married. Only 18.5% are urban and 28% of them have completed middle school education. The vast majority are Han Chinese. Nearly half of the parents have the habit of smoking and drinking in the past year. From the perspective of household characteristic variables, the average annual household income is 38,470 yuan. The average bride price (including the cost of the wedding house) paid is about 59,770 yuan. The fact that average bride price more than the annual income of the household emphasizes the economic burden caused by the bride price. The standard deviation of bride price (in 10,000 yuan) is about 13.33 with the maximum exceeding five million yuan, indicating large variations in bride price spending across households. The average value of the dowry expenditure (including the cost of the wedding house) is about 5454 yuan, much lower than the average level of the bride price, which means bride price is a more common custom than dowry in China. Throughout the whole regression samples, there are about three children per family and 37% of the parents live with their children. The average education level of children is 9.6 years, which is above middle school education. In addition, the average sex ratio of marriageable age in different cities is 1.064, which is greater than 1, indicating that there is a widespread gender imbalance in China.

| Variables | Observations | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health score (1–5) | 12,842 | 2.969 | 1.014 | 1 | 5 |

| Bride price (×104 yuan) | 12,842 | 5.977 | 13.331 | 0 | 513.198 |

| Dowry (×103 yuan) | 12,842 | 5.454 | 24.227 | 0 | 1298.896 |

| Age | 12,842 | 65.803 | 8.807 | 45 | 85 |

| Male | 12,842 | 0.450 | 0.498 | 0 | 1 |

| Married | 12,842 | 0.825 | 0.380 | 0 | 1 |

| Middle school | 12,842 | 0.278 | 0.448 | 0 | 1 |

| Hukou | 12,842 | 0.185 | 0.389 | 0 | 1 |

| Han Chinese | 12,842 | 0.923 | 0.266 | 0 | 1 |

| Drinking or smoking last year | 12,842 | 0.426 | 0.496 | 0 | 1 |

| Household income (×104 yuan) | 12,842 | 3.847 | 8.681 | 0 | 531.8 |

| Living with children | 12,842 | 0.374 | 0.484 | 0 | 1 |

| Number of children | 12,842 | 3.405 | 1.740 | 1 | 15 |

| Sex ratio | 12,842 | 1.064 | 0.161 | 0.901 | 1.215 |

| Children average education | 12,842 | 9.643 | 3.587 | 0 | 22 |

4 RESULTS

4.1 Baseline results

Column (1) in Table 2 shows the results from ordinary least square estimation of the first stage equation. It shows that higher sex ratio will cause higher bride price. This finding is consistent with our expectation. Higher sex ratio implies a higher competition among the males in the marriage market. Specifically, we find that 1 unit increase in the sex ratio is associated with 1.748 unit increase in the amount of the bride price payment (in 10,000 yuan), and the effect is significant at the 10% significance level. The F-statistics of the first stages with control variables is 18.72, indicating that there is no presence of weak instrument. Column (2) reports the causal effect of the bride price on the health of parents from the control function approach. we find a significant and negative impact on the health score. After accounting for individual, household level differences and city fixed effects, the bride price is negatively associated with parent's health outcomes. It shows that higher bride price payment lowers health score. In the results, the plug-in first stage error is significant at the 1% level, confirming that the bride price is endogenous. In contrast, we find a positive coefficient in Column (3) based on regression without addressing endogeneity issue. It Implies that the endogeneity of bride price totally distorts its causal relationship with health score.

(1) First stage (D.v. = Bride price) |

(2) Second stage (D.v. = Health) |

(3) Without addressing endogeneity |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex ratio | 2.111* | ||

| (1.219) | |||

| Bride price | −0.283*** | 0.005** | |

| (0.058) | (0.002) | ||

| Age | −0.266*** | −0.096*** | −0.017*** |

| (0.032) | (0.016) | (0.004) | |

| Male | −0.415 | −0.094 | 0.020 |

| (0.305) | (0.061) | (0.057) | |

| Married | −0.360 | −0.150** | −0.030 |

| (0.345) | (0.076) | (0.071) | |

| Middle School | 2.084*** | 0.859*** | 0.254*** |

| (0.575) | (0.131) | (0.055) | |

| Hukou | 2.552*** | 0.811*** | 0.070 |

| (0.599) | (0.168) | (0.073) | |

| Han Chinese | 0.756 | 0.258** | 0.057 |

| (1.015) | (0.123) | (0.114) | |

| Drinking or Smoking | 0.601 | 0.528*** | 0.361*** |

| (0.341) | (0.067) | (0.058) | |

| Ln (income) | 0.527*** | 0.200*** | 0.049*** |

| (0.097) | (0.035) | (0.013) | |

| Living with children | −1.124*** | −0.292*** | 0.027 |

| (0.383) | (0.081) | (0.053) | |

| Number of children | 0.159 | 0.004 | −0.046** |

| (0.132) | (0.021) | (0.018) | |

| Ln (dowry) | 0.028 | 0.019*** | 0.010** |

| (0.043) | (0.006) | (0.005) | |

| Children education | 0.376*** | 0.119*** | 0.010 |

| (0.062) | (0.023) | (0.007) | |

| City fixed effect | √ | √ | √ |

| First-stage error | 0.289*** | ||

| (0.058) | |||

| N | 12,842 | 12,842 | 12,842 |

| R2 (Pseudo R2) | 0.129 | 0.041 | 0.041 |

| First-stage F-stat. | 18.72 | — | — |

| DWH p-value | — | 0.000 | — |

- Note: All results are the second stage estimation of the control function approach with the sex ratio as the instrumental variable. The first stage regressions are carried out with OLS. Fitted residuals from first stage are incorporated in the second stage ordered logit regression. Robust standard errors adjusted for clustering at the city level are given in parentheses. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% respectively.

4.2 Robustness check and heterogeneity

We check the robustness of our results by looking at different health measures. We also investigate if the effect is sensitive to alternative definitions of sample. All results presented in this section are derived from estimation of the two-stage control function approach of Equation (1).

Since self-reported health is subjective and is subject to justification bias (Disney et al., 2006; McGarry, 2004), we use objective health measures as a robustness check in this section. We adopt two indices of self-care ability to measure physical health—ADL and IADL. ADL measures the ability to complete basic self-care tasks developed as older adults. These tasks include dressing, eating, bathing, getting into or out of bed, toileting, controlling urination and defecation. Survey respondents were asked if they have difficulty with completing these tasks. IADL refers to activities that require more complex thinking and organizational skills. They include housecleaning, shopping, preparing for meals, making phone calls, taking medications, and managing financial accounts. ADL and IADL are measured as the number of activities respondents can complete independently out of the six activities in each category. We categorized respondents as ADL disabled or IADL disabled if they reported needing help in performing any of the six activities respectively (Zhang et al., 2017).

Considering the endogeneity of bride price, we use the average sex ratio faced by the sons within a family as the instrumental variable, reflecting the degree of gender imbalance in the marriage market. When there was no widespread population migration, the marriage market was usually confined to areas with the similar cultural customs, and people tended to find their marital spouse in the same city. However, with the development of economy and the acceleration of urbanization, the population flow has broken the traditional intermarriage circle, and marriageable men or women have got a wider choice of spouses, which means it may not be accurate to average city-level sex ratio to measure gender imbalance in the marriage market. To reduce the error caused by population migration, we exclude the samples with migration for a robustness check. CHARLS survey is conducted with four waves in 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2018, each of which involves asking respondents where they live. If respondents answered in all waves that their current address was the same as that of the last wave, and the first time they moved to their current address was before 2000, they were considered to have no migration in nearly 20 years, otherwise they were deemed to have moved.

In addition, we recode the health score, which is a categorical variable from 1 to 5, as a dummy variable. The new dummy variable is one if the health score is higher than or it equals to 3. Otherwise, it equals to 0. We check whether our conclusion is robust with this setting. We also assume the wives could be 5 years younger than their husband rather than 3 years. We recalculate the average sex ratio and use it as new instrument variable as a robustness check.

Table 3 reports the results of the robustness checks. The first two columns present outcomes with alternative health measures estimated by the control function approach where the second step involves logit regression. Columns (1) and (2) show the effect of the bride price on ADL disability and IADL disability respectively. The results indicate that the effect of bride price on ADL disability and IADL disability are both positive and significant at the 1% significance level. To sum up, the negative impact of the bride price is consistent across different dimensions of health and wellness, employing both subjective and objective measures. Homoplastically, Column (3) shows that the impact is negative and robust after removing the samples with migration. In Column (4), we find that the bride price is negatively associated with health status. A higher bride price payment will lead to lower health status, and significant at 1% level. We also assume the wives could be 5 years younger than their husband and reanalyzed it. The results are reported in Column (5). It validates that the bride price payments have a negative impact on health outcome.

| Full sample | With no migration | Using dummy variable | Using 5 years | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADL disability | IADL disability | Health score | Health | Health score | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Bride price | 0.414*** | 0.371*** | −0.306*** | −0.431*** | −0.145*** |

| (0.091) | (0.086) | (0.066) | (0.076) | (0.045) | |

| Individual characteristics | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Household characteristics | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| City fixed effect | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| N | 12,827 | 12,840 | 10,066 | 12,842 | 12,842 |

- Note: All results are the second stage estimation of the control function approach with the sex ratio as the instrumental variable. The first stage regressions are carried out with OLS. Fitted residuals from first stage are incorporated in the second stage ordered logit regression. Robust standard errors adjusted for clustering at the city level are given in parentheses. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% respectively.

We further explore how the health effect varies by hukou type, age, and gender. We add an interaction term of each of these three variables with bride price in our model and report the main coefficients in Table 4. Heterogenous effects across urban and rural areas are shown in upper panel of Table 4. The bride price payment has a negative impact on rural region. In addition, we find that the coefficients in urban area are significantly larger in absolute value than that in rural area, indicating that there are heterogenous effects across the two regions. In the middle panel, we segment our sample by the age cutoff of 65 years old to define middle-aged parents and elderly parents. We observe a negative impact of bride price payment on parental health, while no heterogeneity across the two groups. In the lower panel, we further explore the heterogeneous effects of bride price on fathers and mothers. It shows that the bride price has no heterogeneous impacts on the health of fathers and mothers.

| Samples | Coefficient | Standard error | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bride price | −0.283*** | (0.059) | 12,842 |

| Bride price* Urban | −0.006** | (0.003) | |

| Bride price | −0.267*** | (0.059) | 12,757 |

| Bride price* Middle-aged | −0.003 | (0.004) | |

| Bride price | −0.285*** | (0.059) | 12,842 |

| Bride price* Male | 0.004 | (0.003) |

- Note: All results are the second stage estimation of the control function approach with subsamples. The outcomes are the self-reported health scores. The first stage analysis is carried out with OLS regressions of the bride price on the exogenous variables including the sex ratio. Fitted residuals from first stage are incorporated in the second stage ordered logit regression. Robust standard errors adjusted for clustering at the city level are given in parentheses. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% respectively.

4.3 Mechanisms

In this section, we examine potential mechanisms that could explain the impact of the bride price payment on health outcomes. We propose three possible channels. First, a higher level of the bride price increases personal debts. With rapid economic development and unbalanced sex ratio, the bride price has risen sharply in the past decades. This imposes a heavy economic burden to the groom's family. For example, given that the average bride price paid is three times the average per capita household annual income among rural residents, rural parents probably have to borrow from relatives, friends or financial institutions to finance the marriage payment. The relationship between financial difficulties and self-reported health or physical functioning has been well established (Drentea & Lavrakas, 2000; Turunen & Hiilamo, 2014). As such, indebtedness caused by high bride price is expected to cause health to decline. We formally test whether the bride price leads to debts by extending our main analysis to examine the impact of the bride price on indebtedness. We use the responses to the CHARLS survey questions “What is the total amount of unpaid loans/credit card debts/money you owe to other families, individuals, or employers?” to measure the parent's personal debt and determine whether the respondent has any unpaid debt at the time of survey. The result is reported in column (1) of Table 5. Accounting for the full set of control variables as well as the city fixed effect, we find that bride price is found to raise the household debt and significant at 10% level.

| Debt | Depression | Work hours | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (2) | |

| Bride price | 1.453* | 0.565** | 0.354*** |

| (0.790) | (0.024) | (0.021) | |

| Individual characteristics | √ | √ | √ |

| Household characteristics | √ | √ | √ |

| City fixed effect | √ | √ | √ |

| N | 12,842 | 12,612 | 12,786 |

| DWH p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

- Note: All results are the second stage estimation of the control function approach. The first stage analysis is carried out with OLS regressions of the bride price on the exogenous variables including the sex ratio. Fitted values of the logged bride price from first stage are incorporated in the second stage logit regression. Robust standard errors adjusted for clustering at the city level are given in parentheses. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% respectively.

Second, psychological distress can represent another channel through which the bride price can impact health. Under Chinese traditional ideology, Confucian culture emphasizes a specific timing of establishment to attain a new and independent family by age 30. Chinese parents will be at a heightened risk of depression and feel stressed with regard to children's overage singlehood (Chen & Tong, 2021). The bride price can be seen as a competitive chip prepared by parents for their sons to cope with the marriage market of gender imbalance, reflecting to some extent the urgency and anxiety of the parents who want their sons to settle down. In addition, previous literature has shown a positive association between debt and psychological depression (Bridges & Disney, 2010; Gathergood, 2012). With the financial debt owed by bride price, parents' psychological pressure increases imperceptibly. This channel is justified by estimating the effect of the bride price on psychological stress using the control function approach with logit regression. In our study, psychological stress is evaluated based on the 10 questions from the CHARLS Depression Scale (CES-D). Each question was scored on a 0–3 scale, with three points for feeling bothered most of the time, and 0 points for feeling hopeful most of the time. The degree of depression is measured as the total score out of the 10 questions. A higher score stands for a higher degree of depression and more psychological stress. Following Liao et al. (2020), the outcome of interest is whether the respondent is at a risk of depression with a cutoff score of 10. Column (2) in Table 5 presents the results. We find that the bride price increases depression level of parents. The effect is significant at 5% significance level.

Third, given that high bride price become a burden to parents, especially for relatively low-income family, parents may increase their work hours to enhance their income, which may undermine their health. Therefore, we check whether the bride price payment increase the likelihood of excessive working hours in Column (3), where the outcome variable is an indicator that the parents work more than 8 h daily. We find that higher bride price payment increases the likelihood of excessive work undertaken by parents. The effect is significant at 1% significance level. This validates that high bride price can undermine parental health through increasing work hours.

Taken together, our empirical results provide evidence that the bride price causes health to deteriorate by increasing financial indebtedness, psychological stress, and work hours. After paying a high bride price, both parents' financial status and psychological status suffer a hit, work hours increase, and self-reported health gets worse.

5 CONCLUDING REMARKS

The recent rise of the bride price in China has raised increasing concerns about its adverse impact on women, families, and possible spillovers to the entire society. However, one important but missing part is the effect of increasing bride price on the well-being of parents of the newlyweds. In this paper, we use data from the CHRLS to investigate the causal impact of the bride price on the health outcomes of parents. To address endogeneity problems caused by omitted variables and reverse causality, we implement the control function method and use the average sex ratio as the instrumental variable for the bride price.

The results show that the bride price significantly worsens parental self-reported health status, with individual characteristics, household characteristics, and city fixed effects fully controlled for. This pattern is consistent with alternative measures of physical functions. Restricting the sample to households with no migration also reveals a significant negative impact on the intensive margin. We explore heterogeneity across hukou type, age, and gender, and find that heterogenous effect exists across rural area and urban area. In addition, we identify three mechanisms that drive the result. First, bride price payment increases personal debts among parents, which imposes the heightened financial burden to life. Second, the bride price, a bargaining chip of sons to compete for a spouse, aggravates parents' psychological pressure. Third, bride price makes parents increase their work hours and undermines their health.

This paper aims at emphasizing an understudied intergenerational impact of the bride price. While we examine the impact of the bride price on parents' health in the Chinese context, this pattern could also exist in other parts of the world where such marriage custom exists. Future research pursuing the same research question in different cultural contexts would be complementary to our analysis. With the aging of the population, this study also contributes to our understanding of health dynamics among the elderly, which is of critical public policy concern. In addition, the groom paying higher bride price tend to marry a higher quality bride. This might increase the health outcome of parents. Therefore, it could be very interesting that future study investigates this in a long run within a theoretical framework.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

REFERENCES

- 1 This paper is based on cross sectional data of CHARLS (2018). Parents' health refers to their health status in the year interviewed, and the bride price expenditure of sons is the sum of all betrothal spending adjusted to the interviewed year by CPI index, which will be explained in detail later.

- 2 The total annual household income includes the salary and transfer income of the respondents and other household members, agricultural income, self-employed or private enterprises income, household public transfer income, and so on.