Housing Security, Relative Deprivation, and Subjective Well-Being: Empirical Evidence Derived From CFPS Data

ABSTRACT

The housing issue significantly influences individuals' well-being. As a crucial mechanism for alleviating the housing issue, the housing security system has garnered increasing attention regarding its impact on residents' happiness. Utilizing data from the China Household Tracking Survey (CFPS), this paper seeks to thoroughly investigate the effect of housing security on residents' subjective well-being and examine the mediating role and regulatory mechanisms of relative deprivation, particularly concerning income and consumption factors. The findings reveal that (1) compared to uninsured families, those with access to housing security experience a marked enhancement in overall happiness levels, indicating that the housing security system exerts a positive marginal effect on improving happiness among covered households. (2) Heterogeneity analysis indicates that the beneficial impact of housing security on subjective well-being is consistent across various age groups, with the most pronounced effects observed in individuals aged 26–40. For households facing low housing affordability, there exists a significantly positive correlation between housing security and subjective well-being—this relationship is even stronger than indicated by baseline regression results. Regional analyses demonstrate that housing security positively affects residents' subjective well-being in eastern and central China but negatively impacts those in western regions; notably, this effect is significant only for eastern Chinese residents. (3) Further exploration revealed that first, housing security substantially mitigates families' sense of income relative deprivation which subsequently enhances their subjective well-being; second, after controlling for household consumption disparities, we observe an increase in the coefficient associated with housing security compared to baseline regression outcomes—suggesting that differences in household consumption may attenuate the positive influence of housing security on happiness. This research not only elucidates the tangible effects of existing housing policies but also provides empirical evidence and theoretical support for government efforts aimed at formulating more precise policies designed to enhance residents' satisfaction.

1 Introduction

The issue of housing is pivotal to public welfare. Third Plenary Session of the 20th CPC Central Committee explicitly emphasized the need to “further deepen reform across the board,” “use economic system reform as a driving force, promote social fairness and justice and enhance people's welfare as both a starting point and ultimate goal, paying more attention to system integration, highlighting key priorities, and emphasizing the effectiveness of reforms.” It profoundly states that “safeguarding and improving people's livelihoods amidst development is a major task of Chinese modernization,” “perfecting the basic public service system, enhancing universal, fundamental, and inclusive welfare projects, tackling the most pressing, direct, and realistic interests of the people, and continuously fulfilling the people's aspirations for a better life.” Housing security is a crucial component of this mission. President Xi also underscores that “reform and development ultimately aim to create better lives,” further illuminating the reform's fundamental purpose and normative orientation in housing security systems. For residents of affordable housing, the emphasis often lies in their personal, microlevel housing experience. Therefore, establishing a model that explores the relationship between housing security and residents' subjective well-being (SWB) holds significant policy relevance in promoting precise policy and enhancing effectiveness and fairness, as well as concrete significance in enhancing citizens' welfare.

China has gradually established a housing security system primarily focused on allocations that incorporates both rentals and sales, especially rentals. It greatly alleviates housing difficulties for residents. Most notably, since the 18th CPC National Congress, China has constructed the world's largest housing security system, with over 60 million units built, ensuring basic housing rights for low-income and households, granting over 150 million people's homeownership. However, the evaluation of institutional reform's success requires balancing the enhancement of economic performance while deeply scrutinizing its profound effects on the overall welfare of the populace (Ferrara et al. 2022). An increasing number of scholars have identified that, aside from individual factors such as age, marriage, education, and income, socioeconomic policies, public services, and living environments significantly affect residents' SWB (Duncan 2010; Latreille et al. 2024). The housing security system operates as a social assurance mechanism in the housing sector, fundamentally leveraging national and societal strengths through redistributive means to accommodate low-middle-income individuals, groups with housing difficulties, and other specific social segments by providing rental and sale of secure housing or rent subsidies to meet fundamental housing needs. Generally, families benefiting from housing security perceive an acquisition of housing transfer income or a reduction in housing expenditures, potentially intensifying their sense of well-being.

Currently, housing security has transitioned from merely focusing on the survival aspect of residence to addressing broader livelihood and developmental needs (Zong and Chen 2021). Thus, from both a macropolicy implementation perspective and a microperspective of enhancing resident welfare, it is crucial to explore how housing security impacts SWB.

2 Literature Review and Hypothesis

2.1 Literature Review

Happiness, alternatively known as SWB, is considered a “hidden national wealth” and serves as a vital metric for assessing residents' quality of life and societal welfare (Lu et al. 2017). During the 1960s to 1980s, research on SWB emerged as a focal point in psychology, gradually integrating into sociological and economic domains (Ouyang and Zhang 2018). Given its relevance to economic–social welfare, scholars have suggested incorporating SWB as an indicator for evaluating national economic and life quality (Diener 2000). In the economic field, maximizing social welfare is the ultimate goal of public policy, whereas subjective evaluations of individual form a crucial aspect of exploring bounded rationality. Consequently, an increasing number of scholars are probing the determinants of residents' SWB. Existing research recognizes personal income, employment status, health, housing prices (Kang and Park 2023), public housing environment (Latreille et al. 2024), social structures, government quality, natural environment, and urban planning as influential factors.

Housing is residents' essential living need and a primary determinant of their well-being (González et al. 2024), especially in China, where “settledness” embodies traditional familial aspirations. Both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights recognized adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living (González et al. 2024). The United Nations General Comment No. 4 (1991) on adequate housing encompasses legal guarantees of housing rights, affordability, appropriateness, and equitable housing opportunities. In other words, the right to housing includes the right to housing security, access to and ownership of housing in the market (Lyu et al. 2020). This signifies that housing transcends mere shelter, symbolizing dignified living and reflecting living standards and well-being.

As a societal welfare system, housing security must transcend focusing solely on socioeconomic performance, considering holistic influences on public welfare (Ferrara et al. 2022). The system chiefly aims through governmental or societal intervention to aid those economically disadvantaged in acquiring suitable housing, thereby diminishing residential cost pressures, reducing anxiety and discontent stemming from housing burdens, and subsequently enhancing residents' SWB (Leng and Zhu 2021; González et al. 2024; Latreille et al. 2024). Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 1.Housing security significantly enhances residents' SWB.

Housing security aspires to eliminate economic-based residential disparities, enhancing residents' welfare (Juvenius 2024). However, individual characteristics, familial circumstances, and regional differences create varied housing preferences and conditions, which in turn modulate housing security's effect on SWB across demographics. Some scholars suggest complex similarities and differences between young and old populations, underscoring public housing's crucial role in young individuals' well-being (Latreille et al. 2024), while living environments disproportionately affect happiness across age groups (Reece et al. 2024). Additionally, housing security has such a close relationship with the burden of housing costs that it can be seen as a governmental wealth transfer, enhancing financial capability or reducing housing expenditures (H. Li et al. 2020), subsequently decreasing overworking and enhancing happiness (C. Zhang et al. 2023). Studies also indicate that housing welfare policies, such as public rental housing, alleviate housing cost burdens for disadvantaged and low-income families, improving psychological well-being (Kim et al. 2023; Gu and Zhu 2024). Moreover, given the vast regional disparities in urbanization, population growth, and housing demand–supply structures, rental costs and housing prices exhibit localized segmentation (Ozabor et al. 2024). This disparate pressure on housing affordability presents an inconsistent welfare effect across regions (Sun et al. 2024), leading to differential impacts of housing policy. Consequently, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2a.Residents' SWB correlates with age, housing affordability, and geographic location.

Hypothesis 2b.Housing security's influence on SWB varies among demographic groups.

Housing security primarily manifests through in-kind allocations and monetary subsidies. The former distributes based on stipulated per capita space usage, assigning rents slightly below market rates (generally 10%–20% discounts), whereas the latter issues monetary subsidies based on “market pricing, tiered subsidy, subsidy-separation” principles. These methods essentially mitigate household housing burdens or enhance financial capacities. Moreover, policy implementation alters residents' previous perceptions of relative deprivation due to suboptimal housing or financial pressure, a state where individuals compare their situation to others and feel discontent upon recognizing possessed deficits (Runciman 1966). Intensified feelings of relative deprivation in consumption can lead to heightened status anxiety, resulting in multifaceted psychological, physiological, and societal repercussions (Hastings 2019; Chen et al. 2024). Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 3a.Housing security alleviates residents' income-based relative deprivation, thereby enhancing SWB.

Hypothesis 3b.Consumption-relative deprivation adversely modulates the welfare effect of housing security.

3 China's Housing Security Policy

Before conducting the empirical analysis, it is essential to provide a concise overview of China's housing security system to understand its impact on the SWB of residents better. Housing security refers to the government's responsibility to address the housing difficulties faced by specific groups, ensuring all members of society have access to adequate shelter. In contrast to commercial housing, affordable housing possesses certain social welfare and security functions. It is directly or indirectly funded by the government and provided to low-income families with housing difficulties at prices below market levels through rental or sale.

Since the founding of the People's Republic of China, the Chinese government has placed significant emphasis on addressing the housing needs of urban and rural residents. On one hand, China has continuously explored and refined a housing security system with Chinese characteristics. From the implementation of public housing ownership under the planned economy system and housing security for the entire society to the gradual establishment of the socialist market economy system alongside the commercialization and marketization reforms of housing, efforts have been made to promote the construction of a housing security system centered on allocation and sale. On the other hand, successive governments have steadily increased the construction of affordable housing in accordance with the principle of “doing their best within their capacity.”

From 1949 to 1978, aligned with the planned economy system, after the establishment of public housing ownership, China implemented a public housing physical distribution system characterized by “unified management, unified allocation, and rental support,” also known as the welfare housing distribution system. The Third Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee of the Communist Party of China in 1978 initiated economic reforms while simultaneously launching housing reforms centered on housing commercialization. However, the welfare-oriented physical distribution system was not fully terminated until 1998. During this period, a rental-based housing security system covering the entire society was effectively implemented.

Between 1978 and 2007, China experienced four decades of rapid economic development and comprehensive economic system reform. Over these 40 years, with the gradual establishment of a monetized and commercialized housing system and the rise of the real estate industry, China's housing security underwent a series of reforms and explorations, establishing a housing security system primarily comprising affordable housing, low-rent housing, and housing provident funds.

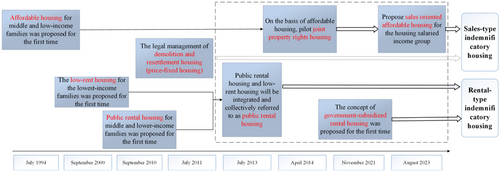

Since 2008, China's housing system has emphasized both security and market development equally. After completing the marketization of housing, the focus of housing system reform shifted to improving the housing security system. Through years of exploration, the housing security system based on both rent and sale has been further refined. The former mainly consists of public rental housing (including low-rent housing) and government-subsidized rental housing, whereas the latter has evolved from affordable housing through Joint property rights housing to the “sales-oriented affordable housing” proposed in 2023 (as shown in Figure 1).

The four types of indemnificatory housing—public rental housing, government-subsidized rental housing, Joint property rights housing, and sales-oriented affordable housing—complement each other in terms of guarantee mechanisms, target groups, eligibility criteria, construction entities, and land supply. It can be said that a housing security system meeting the requirements of the times and reflecting the interests of the people has been established (as shown in Table 1).

| Safeguard measures | Method | Object | Admission criteria | Construction entity | Land supply |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lease protection | Public rental housing | Families with housing difficulties and income difficulties in urban areas | There are restrictions on household registration, length of residence, and income | Government-led | Transfer |

| Government-subsidized rental housing | New citizens, young people, and so forth | No | Multisubject investment and construction | Assignment, lease, or transfer | |

| Property rights protection | Joint property rights housing | Urban low-and middle-income households | There are restrictions on household registration, length of residence, and income | Led by the government, urban investment enterprises are more likely to undertake construction tasks | Allocation or assignment |

| Sales-oriented affordable housing | Wage earners with housing difficulties and low incomes, and those who need to introduce talents in the city | Noa | Government-led, strictly closed management | Allocation and stock of land |

- a There are no clear entry standards for the allocation type of public rental housing for the time being. It is set up by local governments on their own. The allocation will be made in sequence based on the applicant's family income, housing, property, and other factors, starting from the most difficult groups and gradually expanding the scope.

4 Data, Empirical Model, and Variables

4.1 Data

The data utilized in this article are sourced from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) conducted in 2014 and 2018. These datasets encompass three levels: individual, family, and community, and incorporate various economic indicators such as household income, expenditure, housing, assets, and debts. Additionally, they include personal information of family members, including age, gender, education, employment status, health conditions, subjective attitudes toward relevant issues, and cognitive test results. The indicator data actually employed in this study primarily originate from the household economic questionnaires and individual self-reported questionnaires within the CFPS database. The dependent variable in this article is SWB, whereas the core explanatory variable pertains to whether housing security has been obtained. Due to the significant deficiency of the “SWB” indicator data in the databases for 2016 and 2012 (with a missing rate of 95%) and the absence of questions or options related to affordable housing in the 2010 questionnaire, this study exclusively utilizes the family economic questionnaires and individual self-reported questionnaires from the CFPS database for 2014 and 2018.

To ensure the reliability of our empirical findings, we implemented several rigorous preprocessing steps. First, to maintain sample comparability, we retained only those households currently residing in nonowned accommodations. Second, acknowledging potential biases arising from disparities in housing security policy implementation across cities and uneven urban sample distribution, we excluded cities with a sample size below 30. This exclusion encompassed six cities located in Inner Mongolia, as well as Ningxia, Xinjiang, Hainan, Tibet, and Qinghai. Third, to mitigate bias stemming from the age of household heads, we restricted their ages to the range of 18–65 years. Fourth, in consideration of data integrity and continuity, we eliminated samples with missing or invalid values for key indicators. Fifth, to address the potential distortion of empirical outcomes by outliers among sample indicators, we applied a tail reduction of 1% on each continuous economic indicator, such as household income and debt. Lastly, we matched regional-level indicator data, including housing prices and consumer price indices, primarily sourced from the National Bureau of Statistics. Ultimately, this meticulous preprocessing process yielded a total of 3441 observations.

4.2 Empirical Model

represents the SWB of respondent in province of year . indicates whether the respondent has received housing security. is a set of control variables, including individual level, family level, and local level factors. is the year fixed effect, is the province fixed effect, and is the random error term.

4.3 Definition of Key Variables

4.3.1 Dependent Variable: SWB (Well_Being)

The dependent variable was residents' SWB, which was quantified by utilizing the scoring system for individual SWB as outlined in the methodology employed by Gu and Zhu (2024). Specifically, the CFPS database incorporated a question inquiring about participants' happiness levels, scored on a scale ranging from 0 (indicating the lowest level of happiness) to 10 (representing the highest level of happiness). The SWB variables are categorized as ordered multivariate discrete variables, with their respective values encompassing the entire numeric sequence from 0 to 10 inclusive (i.e., “0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10”).

4.3.2 Independent Variable: Whether to Obtain Housing Security (Housing_Security)

As a social welfare system, housing security aims to solve the housing problem of low-and middle-income families. It is guaranteed in two ways: physical allocation of rent (only rent and not sale) and monetary subsidies, so as to reduce the economic burden of residents' housing and improve their living conditions. Our explanatory variable is a binary variable, that is, getting Housing_security or not, 1 if Housing_security is obtained, 0 if not. Specifically, according to the CFPS database question, “Who owns the house your family currently lives in?” The sample of families with full property rights and partial property rights will be deleted, and families that have obtained “public housing (houses provided by units)” or “low-rent housing” or “public housing” will be identified as having obtained housing security, and others will be identified as having no housing security.

4.3.3 Control Variables

The control variables involved include the individual characteristics of the head of household, the family characteristics, and the economic characteristics of the province where the family resides. First, the individual characteristic variables of the head of household include age, age squared/100, marital status, years of education, hukou status, and working status. There is no clear definition of a head of household in the CFPS database, and we use the family member referred to by “financial respondent” in the CFPS database in 2014 and 2018 as the head of household. Among them, age refers to the actual age of the household head when completing the questionnaire. The influence of life cycle is taken into account in the age-squared term, and the value of the age-squared term is reduced by 100 times. The marital status is set according to the “current marital status” of the head of household in the CFPS database. The years of education were measured by the “highest degree completed by the respondent” in the CFPS database. We recorded no schooling/illiteracy/semi-illiteracy as 0, primary school as 6, junior high school as 9, high school/technical school/vocational high school as 12, junior college as 15, bachelor's degree as 16, master's degree as 19, doctor's degree as 22. The account status is set according to the “current account status” of the owner in the CFPS database. The working status is set according to the “current working status” of the owner in the CFPS database. Second, family characteristic variables include family size, elderly dependency ratio, child dependency ratio, per capita disposable income, total assets, and total liabilities of the family. Among them, the original index data of “family population size” in the CFPS database are used for family population size. The old-age dependency ratio is expressed by the ratio of the number of people aged 65 and over to the number of people aged 16–64 in the household. The child dependency ratio is expressed by the proportion of the population aged 15 and under to the population aged 16–64. The per capita disposable income of a household is calculated by the ratio of the sum of wage, business, property, transfer, and other income to the household size. The total household assets are composed of household housing assets, land assets, financial assets, productive fixed assets, and durable consumer goods. Total household debt consists of household housing debt and general debt. Finally, the characteristic variables at the provincial level include housing prices and the Consumer Price Index (last year = 100). The main variable definitions and statistical descriptions are shown in Table 2.

| Variable | Definition | Obs | Mean | Std. dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing_security | Obtain housing security = 1, otherwise = 0 | 3441 | 0.298 | 0.458 | 0 | 1 |

| Well-being | Subjective well-being score (1 being lowest, 10 being highest) | 3441 | 7.157 | 2.210 | 0 | 10 |

| Age | Age | 3441 | 38.53 | 12.53 | 18 | 65 |

| Age2 | Age squared/100 | 3441 | 16.42 | 10.39 | 3.240 | 42.25 |

| Mar | Marital status | 3441 | ||||

| Mar_1 | Unmarried | 3441 | 0.207 | 0.405 | 0 | 1 |

| Mar_2 | Be married | 3441 | 0.717 | 0.451 | 0 | 1 |

| Mar_3 | Divorced or widowed | 3441 | 0.0761 | 0.265 | 0 | 1 |

| Edu | Educational level | 3441 | ||||

| Edu_0 | Illiterate or semi-illiterate | 3441 | 0.094 | 0.292 | 0 | 1 |

| Edu_6 | Primary school | 3441 | 0.153 | 0.360 | 0 | 1 |

| Edu_9 | Junior high school | 3441 | 0.327 | 0.469 | 0 | 1 |

| Edu_12 | High school or secondary school or technical school or vocational | 3441 | 0.210 | 0.407 | 0 | 1 |

| Edu_15 | High school | 3441 | 0.117 | 0.322 | 0 | 1 |

| Edu_16 | Junior college Undergraduate |

3441 | 0.0889 | 0.285 | 0 | 1 |

| Edu_19 | Master | 3441 | 0.00959 | 0.0975 | 0 | 1 |

| Edu_22 | Learned scholar | 3441 | 0.000291 | 0.0170 | 0 | 1 |

| Regist | Nonfarm account = 1, otherwise = 0 | 3441 | 0.330 | 0.470 | 0 | 1 |

| Work | Having a job = 1, otherwise = 0 | 3441 | 0.800 | 0.400 | 0 | 1 |

| Familysize | Number of people in all households | 3441 | ||||

| 1 | 3441 | 0.283 | 0.451 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2 | 3441 | 0.205 | 0.404 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3 | 3441 | 0.247 | 0.431 | 0 | 1 | |

| 4 | 3441 | 0.145 | 0.352 | 0 | 1 | |

| 5 | 3441 | 0.0695 | 0.254 | 0 | 1 | |

| 6 | 3441 | 0.0317 | 0.175 | 0 | 1 | |

| 7 | 3441 | 0.0186 | 0.135 | 0 | 1 | |

| Old_ratio | Elderly dependency ratio: Population aged 65 and above/population aged 16–64 | 3441 | 0.0507 | 0.210 | 0 | 2 |

| Child_ratio | Child dependency ratio: Population aged 15 and under/population aged 16–64 | 3441 | 0.0369 | 0.163 | 0 | 2 |

| Per_income | Per capita disposable household income | 3441 | 31,584 | 35,225 | 285.7 | 370,000 |

| Total_assets | Total household assets | 3441 | 616,850 | 988,792 | 2300 | 5,800,000 |

| Total_debts | Liabilities = 1, otherwise = 0 | 3441 | 38,755 | 115,046 | 0 | 770,000 |

| H_price | Home province housing prices | 3441 | 9701 | 6357 | 4227 | 33,820 |

| Cpi | Consumer Price Index (previous year = 100) | 3441 | 102.1 | 0.315 | 101.5 | 102.7 |

- Note: Household per capita disposable income, total household income, and total household debt are introduced as logarithms in empirical regression and are presented as absolute numbers in this table.

5 Empirical Results

5.1 Basic Regression Result

Table 3 presents the regression results derived from Model (2) to examine the influence of housing security on family SWB. Specifically, Column (1) not only incorporates the core independent variable “Housing_security” but also comprehensively accounts for individual characteristics of the household head, family attributes, and economic factors pertinent to the province in which the family resides, thereby constructing a more nuanced and detailed regression model. Furthermore, building upon listing (2) in (1), by introducing province fixed effects and year fixed effects, we effectively control for external factors that may vary over time yet remain unobserved, thus enhancing both robustness and reliability of our research conclusions. This extension not only bolsters model robustness but also enriches our understanding of dynamic changes regarding the impact of housing security. Notably, whether considering Column (1) or Column (2), regression results consistently indicate a significantly positive coefficient for the “Housing_security” variable. This finding strongly implies that households with housing security exhibit higher overall levels of SWB compared to those without it. Such evidence substantiates the beneficial role played by housing security systems in enhancing well-being among protected families while revealing significant positive marginal effects through alleviating housing pressures; furthermore, it reaffirms that housing security is an essential component of social safety nets with critical implications for improving livelihoods and promoting residents' welfare.

| Explanatory variables | Well-being | Well-being |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Housing_security | 0.075* | 0.085** |

| (0.040) | (0.040) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes |

| Fe_pro | No | Yes |

| N | 3441 | 3441 |

- Note: This table presents the impact of housing security on residents' subjective well-being, using CFPS data from 2014 and 2018. Columns (1) and (2) respectively list the estimated results without controlling for the year and province fixed effects and with controlling for the year and province fixed effects. The data adopted in this paper are mixed cross-sectional data. The time variable (year) has been included as a common explanatory variable in the regression model to control its influence instead of using time-fixed effects. *, *, and *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively. Robust standard errors clustered at the household level are shown in parentheses.

5.2 Robustness Check

To ensure a high degree of reliability and credibility in the conclusions drawn from the baseline regression analysis, we have employed a series of rigorous and diversified methodologies to conduct robustness tests, aimed at comprehensively verifying the stability and consistency of the model under varying conditions. Specifically, we first implemented a sample replacement strategy whereby 90% of samples were randomly selected from the original full sample set for regression analysis. This step is designed to assess whether the regression results are contingent upon specific sample selections, thereby ensuring the generalizability of our conclusions. Second, we explored alternative explained variables by introducing new metrics based on the baseline regression model (where SWB level scores greater than 5 are coded as 1; otherwise coded as 0) to investigate whether variations in variable definitions affect the stability of regression coefficients. This approach elucidates the model's sensitivity to different metrics, thus enhancing conclusion robustness. Additionally, we conducted a replacement of the regression model itself by substituting the Ordered Logit model utilized in our baseline analysis with an alternative for further examination. This transformation not only assesses dependence on specific models but also reinforces both robustness and adaptability through comparative evaluation of estimated coefficients across different modeling frameworks. The empirical findings are presented in Table 4. Results from all robustness tests consistently indicate that estimated coefficients for our core explanatory variable “Housing_security” remain significantly positive across various testing scenarios. This outcome not only bolsters confidence in our baseline regression results but also clearly demonstrates that housing security exerts a stable and significant positive influence on study variables, thereby thoroughly substantiating their robustness.

| Explanatory variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random sampling 90% | Change the dependent variable | Ologit model | IV | |

| Housing_security | 0.097** | 0.156*** | 0.134* | 2.289*** |

| (0.043) | (0.056) | (0.069) | (0.030) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Fe_province | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 3097 | 3441 | 3441 | 3441 |

- Note: This table uses CFPS data from 2014 and 2018 to present a robustness test of the impact of housing security on residents' subjective well-being. Column (1) represents the estimation results of 90% of the samples randomly sampled. Column (2) represents the estimation results of changing the dependent variable. Column (3) represents the estimation results of changing the regression model. The data adopted in this paper are mixed cross-sectional data. In the regression model, a time variable (year) is added as a universal explanatory variable to control its influence instead of using time-fixed effects. *, *, and *** respectively indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels. The robust standard errors aggregated at the household level are shown in parentheses.

To mitigate potential sample bias, we judiciously employed a methodology known as propensity score matching (PSM) to further enhance and validate our analysis. Specifically, we devised an experimental design framework wherein the success of households in securing housing served as a core variable; consequently, the sample was distinctly categorized into two groups: individuals receiving housing security formed the treatment group (designated treated = 1), whereas those not receiving such support were classified as the control group (designated treated = 0). In implementing the PSM strategy, we systematically utilized various matching techniques to ensure balance and representativeness within samples, including one-to-one matching, one-to-two matching, one-to-three matching, and one-to-four matching. The application of these diverse matching ratios aims to capture and address potential heterogeneity by enhancing the flexibility of matches, thereby improving the generalizability of our findings. As illustrated in Table 5, following data processing and statistical analysis, we observed that the T-value significantly surpassed the critical statistical threshold of 2 across all four adopted matching methods. This outcome not only underscores the statistical significance of the treatment effect but also robustly substantiates the reliability and validity of our benchmark empirical results presented herein. In essence, even after accounting for potential confounding factors related to sample selection bias, our conclusions remain resilient—providing substantial evidence for relevant policy formulation and practical interventions.

| PSM method | Treated | Controls | Difference | S.E. | T-stat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k-Nearest neighbors matching (k = 1) | 7.220 | 6.927 | 0.293 | 0.118 | 2.49 |

| k-Nearest neighbors matching (k = 2) | 7.220 | 6.897 | 0.323 | 0.105 | 3.06 |

| k-Nearest neighbors matching (k = 3) | 7.220 | 6.927 | 0.293 | 0.100 | 2.93 |

| k-Nearest neighbors matching (k = 4) | 7.220 | 6.963 | 0.257 | 0.097 | 2.65 |

Considering that individuals affected by housing security policies may also benefit from other poverty alleviation policies that may affect their well-being. However, it is difficult to control the influence of these related policies in the empirical process. In this regard, this paper takes the land transfer data (logarithm) with the purpose of affordable housing at the provincial level1 as the instrumental variable to alleviate the endogeneity problem. The results are shown in Column (4) of Table 4. The regression coefficients of the key explanatory variables are all significantly positive, strengthening the verification of the robustness of the benchmark regression results in this paper.

5.3 Heterogeneity Analysis

5.3.1 Heterogeneity of Age

The basic fact that an individual's age, as an objective biological and sociological feature, is not subject to the individual's subjective will or preference, constitutes an important premise for subsequent analysis. In this study, to further explore the age difference in the impact of housing security policies on residents' SWB, we accurately divided the whole sample into five distinct subsamples with clear boundaries, namely “18–25 years old,” “26–40 years old,” “41–50 years old,” “51–60 years old,” and “60–65 years old,” according to the key variable of age. It is designed to capture the specific effects of different age groups through careful segmentation.

The results of regression analysis are detailed in Table 6. From the overall trend, no matter the age group, housing security has a positive effect on improving the SWB of residents. This finding reinforces the core position of housing as one of the basic needs of life in shaping people's happiness. It is particularly noteworthy that in the specific age group of “26–40 years old,” the positive effect of housing security not only exists but also has the most significant impact degree and the highest effect size. This finding is closely related to the reality of our society, because this age is often the golden age of an individual's career, and it is also an important stage for most families to experience from formation to parenting. During this period, a stable and suitable housing environment is not only the guarantee of material life but also the source of spiritual comfort, which plays an irreplaceable role in maintaining family harmony and improving the happiness of members. In addition, considering that the “26–40 year old” group generally faces multiple pressures such as greater economic burden, choice of career development path, and responsibility for childcare, the implementation of housing security policy is a solid backing, effectively alleviating their economic anxiety, providing the necessary material security, and thus promoting the significant improvement of SWB. This finding not only enriches the academic research on the effect of housing policies but also provides a scientific basis for policymakers to optimize housing security strategies and maximize social welfare.

| Explanatory variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–25 | 26–40 | 41–50 | 51–60 | 60–65 | |

| housing_security | 0.0381 | 0.114* | 0.0533 | 0.0147 | 0.200 |

| (0.099) | (0.063) | (0.098) | (0.115) | (0.211) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Fe_province | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 554 | 1466 | 715 | 502 | 204 |

- Note: This table uses CFPS data from 2014 and 2018 to demonstrate the impact of housing security on the subjective well-being of residents of different ages. Column (1) represents the estimation results for the 18–25 age group, Column (2) represents the estimation results for the 26–40 age group, Column (3) represents the estimation results for the 41–50 age group, Column (4) represents the estimation results for the 51–60 age group, and Column (5) represents the estimation results for the 61–65 age group. The data adopted in this paper are mixed cross-sectional data. In the regression model, a time variable (year) is added as a universal explanatory variable to control its influence instead of using time-fixed effects. *, *, and *** respectively indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels. The robust standard errors aggregated at the household level are shown in parentheses.

5.3.2 Heterogeneity of Housing Affordability

Generally speaking, the identification of the guaranteed objects includes two basic elements: housing poverty and insufficient housing affordability. Among them, housing affordability refers to the economic ability of a family to rent or buy housing from the market, so it can be divided into rental affordability and purchase affordability. The existing literature suggests that household income has an important relationship with housing affordability. Limited household income is often simplified for two types of expenditure: housing expenditure and nonhousing expenditure. So there are two ways to measure housing affordability. One is to directly consider the relationship between housing expenditure and family income. The second is to consider the relationship between the residual income of the family after deducting the basic nonhousing expenditure and housing expenditure. Based on the different measurement angles above, the existing housing affordability index can be divided into two categories: housing expenditure income ratio index and residual income ratio index. In view of the practical limitations of data acquisition, we prudently focus on the income factor when exploring the overall housing affordability of residents, and choose the classic indicator of housing expenditure to income ratio as an analytical tool. The index measures the affordability of housing by calculating the percentage of housing consumption expenditure (covering rent, facility maintenance costs and related service costs, etc.) in the total disposable income of households. To more carefully analyze the impact of housing affordability on residents' SWB, we sorted all samples according to the value of housing affordability, selected the median as the dividing point, and cleverly divided the samples into two groups, namely, the group with low housing affordability and the group with high housing affordability.

Through empirical regression analysis results summarized in Table 7, we have observed some phenomena worthy of further discussion. In the sample group of low housing affordability, the impact of housing security policy on residents' SWB is significantly positive at the confidence level of 1%, and the positive effect is stronger than that of the benchmark regression model. This finding strongly confirms that the housing security policy has a positive effect on alleviating the housing pressure of residents with low housing affordability and improving their life satisfaction. However, in the sample group of high housing affordability, although the impact of housing security policy is not statistically significant, its direction is negative, suggesting that for residents with relatively good economic conditions, housing security policy may not bring about the expected increase in happiness, and may even have a certain negative effect. These findings not only enrich our understanding of the effects of housing security policies but also provide an important empirical basis for the formulation and optimization of future policies.

| Explanatory variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Low | High | |

| Housing_security | 0.173*** | −0.031 |

| (0.057) | (0.062) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes |

| Fe_province | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1721 | 1720 |

- Note: This table uses CFPS data from 2014 and 2018 to demonstrate the impact of housing security on the subjective well-being of residents with different housing affordability. Column (1) represents the estimated results of low housing affordability, and Column (2) represents the estimated results of high housing affordability. The data adopted in this paper are mixed cross-sectional data. In the regression model, a time variable (year) is added as a universal explanatory variable to control its influence instead of using time-fixed effects. *, *, and *** respectively indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels. The robust standard errors aggregated at the household level are shown in parentheses.

5.3.3 Heterogeneity of Region

According to the geographical location characteristics of the residents, we divided the sample into three regions: eastern, central, and western, aiming to deeply explore the differentiated impact of housing security policies on residents' SWB under different regional backgrounds. Table 8 lists the specific results of subsample regression in detail, from which the following main findings can be summarized: First, from the overall trend, the impact of housing security policy on residents' SWB shows significant regional differences. Specifically, this policy has a positive effect on residents' SWB in the eastern and central regions, indicating that the improvement of housing security in these regions helps to enhance residents' life satisfaction and happiness. However, in the western region, the effect of this policy shows the opposite trend, that is, it has a negative impact on the SWB of residents, which may be related to the specific economic, social, and cultural background in the western region. Second, the impact of housing security policy on residents' SWB is not only different in direction but also shows obvious regional concentration in significance. Specifically, the effect of the policy on residents' SWB reached a statistically significant level only in the eastern region, whereas in the central and western regions, although the direction of its impact was identifiable, it did not reach a statistically significant level. This finding suggests that regional differences should be fully considered in the formulation and implementation of housing security policies, and more targeted and differentiated strategies should be implemented.

| Explanatory variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| East | Central | West | |

| housing_security | 0.100* | 0.094 | −0.032 |

| (0.053) | (0.087) | (0.094) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Fe_province | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1952 | 791 | 698 |

- Note: This table uses CFPS data from 2014 and 2018 to demonstrate the impact of housing security on the subjective well-being of residents in different regions. Column (1) represents the estimation results of the eastern region, Column (2) represents the estimation results of the central region, and Column (3) represents the estimation results of the western region. The data adopted in this paper are mixed cross-sectional data. In the regression model, a time variable (year) is added as a general explanatory variable to control its influence instead of using time-fixed effects. *, *, and *** respectively indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels. The robust standard errors aggregated at the household level are shown in parentheses.

6 Extensibility Analysis

6.1 The Mediating Effect of Income Relative to Sense of Deprivation

Runciman (1966) was the first to define the concept of “relative deprivation,” arguing that relative deprivation should meet the following four conditions at the same time: (1) the individual does not possess X; (2) other individuals in the reference group have X; (3) the individual expects to have X; (4) The individual believes that such expectations are justified. Since then, the concept has been gradually applied to areas such as consumption and income (Fehr and Schmidt 1999; Huang et al. 2019), derived from the concepts of “relative deprivation of income” and “relative deprivation of consumption.” Of course, this can also be understood as an upward social comparison triggered by the psychology of comparison, which is more likely to produce psychological gaps between individuals, inducing “illusions of loss,” which will directly affect people's sense of gain and happiness (Y. Zhang et al. 2022).

In Equation (3), indicates the mean per capita disposable income of all the households in sample group Y, and represents sample group Y in which the per capita disposable income of the households exceeds the mean per capita disposable income of . represents the percentage of the total sample size in which household per capita disposable income exceeds household per capita disposable income in sample Y.

The concept of relative deprivation in household income is inherently relative. Before analyzing the impact of housing security on the sense of relative deprivation in household income, this paper first examines the influence of housing security on household savings2 at the conceptual level of absolute figures. The findings are presented in Column (1) of Table 9, demonstrating that households receiving housing security experience a significant increase in savings. Furthermore, the effect of housing security on the sense of relative deprivation in household income is illustrated in Columns (2) and (3) of Table 9. At a significance level of 5%, the housing security policy exhibits a substantial mitigating effect on the sense of relative deprivation in household income. Specifically, following the implementation of this policy, the perceived degree of relative income deprivation among families has significantly diminished. This change, in turn, positively enhances the SWB of families, as evidenced by a notable improvement in their self-reported well-being.

| Explanatory variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Savings | Income_kak | Well-being | Consumption | Housing_security | Well-being | |

| Housing_security | 0.126* | −0.012** | −0.128*** | |||

| (0.066) | (0.006) | (0.026) | ||||

Housing_security* Income_kak |

0.264* | |||||

| (0.152) | ||||||

| RD_kak | 0.697*** | |||||

| (0.139) | ||||||

Housing_security* RD_kak |

0.166** | |||||

| (0.077) | ||||||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Fe_province | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 3441 | 3441 | 3441 | 3441 | 3441 | 3441 |

- Note: This table uses CFPS data from 2014 and 2018 to demonstrate the influence mechanism of housing security on the sense of happiness in the democratic outlook. Column (1) represents the impact result of housing security on household savings (logarithmic), and column. Column (2) shows the influence results of housing security on the sense of relative deprivation of income. Column (3) shows the influence results of the interaction term of housing security and the sense of relative deprivation of income on residents' subjective well-being. Column (4) represents the impact result of housing security on household consumption (logarithmic). Column (5) shows the influence results of housing security on the sense of relative deprivation of consumption. Column (6) shows the influence results of the interaction term of housing security and the sense of relative deprivation of consumption on residents' subjective well-being. The data adopted in this paper are mixed cross-sectional data. In the regression model, a time variable (year) is added as a general explanatory variable to control its influence instead of using time-fixed effects. *, **, and *** respectively indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels. The robust standard errors aggregated at the household level are shown in parentheses.

6.2 The Moderating Effect of Consumption Differences

In Formula (4), represents the average per capita household consumption of all samples in sample group C, and represents sample group C in which the per capita household consumption exceeds the average per capita consumption of . represents the percentage of samples in sample group C where household per capita consumption exceeds household per capita consumption.

The concept of relative deprivation in household consumption (consumption difference) is also a relative term. Before analyzing the relative deprivation in household consumption (consumption difference) induced by housing security, this study first examines the impact of housing security on household consumption at the conceptual level of absolute figures. As shown in Column (4) of Table 9, the results indicate that household consumption significantly decreases for those receiving housing security, primarily due to reduced housing-related expenditures. Furthermore, the influence of housing security on the relative deprivation of household consumption (consumption difference) is presented in Columns (5) and (6) of Table 9. After incorporating consumption disparity as a variable into the model, the coefficient of housing security demonstrates a significant upward trend compared to the corresponding coefficient in the benchmark regression model. This suggests that after effectively controlling for household consumption differences, the SWB of households has correspondingly improved. In other words, the existence of household consumption disparities weakens the happiness effect generated by housing security. Thus, consumption disparities function as a moderating variable, and its moderating effect has been empirically validated.

7 Conclusions and Policy Implications

With ongoing advancements in housing security policies, their role in enhancing residents' SWB has become increasingly pronounced. By analyzing data from the CFPS through the lens of SWB, we delve into the welfare effects and its disparities within housing security. Empirical findings reveal that housing security significantly boosts SWB. This suggests that housing security, as a social welfare mechanism, effectively enhances residents' well-being potentially by reducing housing financial burdens and alleviating associated psychological anxiety and dissatisfaction. Furthermore, the impact of housing security on SWB exhibits heterogeneity, most prominently within the 26–40 age group and among low housing affordability cohorts. Regional heterogeneity analysis indicates positive impacts on SWB in Eastern and Central regions but presents negative impacts in Western regions, with significance only for residents in the eastern region. Finally, insights from income and consumption-relative deprivation indicate that housing security markedly reduces family income-relative deprivation, thus enhancing family SWB. Concurrently, disparities in consumption can attenuate the positive effects on SWB, signifying the moderating role of consumption disparities in this process.

- 1.

Strengthen the cognition of welfare effect of housing security system: Recognizing that the fundamental purpose of housing security lies in lessening residents' economic pressures and enhancing well-being, policymakers should fully acknowledge the welfare implications of housing policies, employing them as a basis for formulating and adjusting housing strategies. It is crucial to focus on inclusive and precise policy design to ensure equitable and effective distribution of resources to those most in need.

- 2.

Emphasize differentiated policy implementation: Given the multifactorial influences on SWB, housing policies should be executed with differentiation. Findings indicate varying impacts across demographics such as age, education, and income levels. Consequently, policies should cater to individuals' distinctive needs, particularly addressing the 26–40 demographic, who are often in crucial family-forming and child-rearing stages, necessitating stable housing environments. Policy measures should thus increase housing allocation quotas for this key demographic and optimize the mix of in-kind allocations and monetary subsidies.

- 3.

Strengthen regional coordination in housing policy: Considering the geographic disparities in welfare effects, enhancing policy coordination among eastern, central, and western regions is advisable. The eastern regions should continue refining housing systems, focusing on efficiency and quality improvements. central areas need increased policy support to gradually bridge regional gaps, whereas western regions should innovate context-specific housing models, avoiding one-size-fits-all policies that can introduce unintended adverse consequences.

Disclosure

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethics Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

Consent

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.