Soft Power in Trade: Quantifying the Impact of Confucius Institutes on China's Exports

Renjing Chen, Wei Jin, and Tangrui Yang contributed equally to this study.

ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the role of Confucius Institutes (CIs) as a form of China's cultural diplomacy and their impact on international trade, particularly exports. Using a gravity model, we analyze data from 1990 to 2019 across countries, finding that the presence of CIs significantly boosts China's exports. Robustness checks confirm this effect across various specifications, including imports and sector-level data. Mechanism analysis reveals that CIs enhance China's image, increasing trade by fostering positive perceptions abroad. The study further identifies pronounced trade effects in high-income nations, and regions with shorter cultural distance from China. Our findings suggest that cultural output via Confucius Institutes not only advances China's soft power but also serves as a strategic tool to promote trade globally, with differentiated goods benefiting the most.

1 Introduction

Since China's reform and opening-up, its economy has experienced a rapid ascent (Song et al. 2011). With this economic growth, China has progressively expanded its influence across both economic and non-economic spheres. Economically, China has adopted policies of greater openness, evidenced by its participation in free trade agreements such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and by extending its regional and global economic reach through initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (Gao et al. 2024). Politically and militarily, China has strengthened its global presence by actively engaging in United Nations initiatives, enhancing military cooperation with neighboring countries, and co-founding the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. In the realm of international development, China, as a developing nation, has extended aid to the least developed countries, supporting numerous regions across Asia, Africa, and Latin America (Dreher et al. 2021; Eichenauer et al. 2021). As a country with a long-standing cultural heritage, China has also prioritized promoting its culture internationally. The literature underscores cultural output as vital to a nation's overall influence (Rose 2016, 2019; Chang et al. 2022). This paper explores the impact of Confucius Institutes—central to China's cultural outreach—by quantitatively assessing their effect on China's international trade.

The Confucius Institute is a global educational initiative launched by the Chinese government in 2004 to promote Chinese language and culture internationally. Named after the renowned Chinese philosopher Confucius, these institutes operate in collaboration with universities, educational institutions, and organizations worldwide. Their primary mission is to provide Chinese language courses, cultural programming, and resources to help people better understand Chinese culture and foster friendly relations with China. By hosting language classes, cultural events, and educational exchanges, Confucius Institutes serve as a bridge for intercultural understanding, aiming to make Chinese language and culture accessible to a global audience. Since its inception, the Confucius Institute network has grown extensively, becoming a significant part of China's cultural diplomacy. The rapid expansion of Confucius Institutes aligns with China's broader strategy of cultural output, which seeks to boost China's influence globally beyond just economic means. As part of this approach, China has also strengthened its international reach through trade agreements, developmental aid, and active involvement in global organizations like the United Nations and initiatives such as the Belt and Road. However, Confucius Institutes have faced scrutiny and controversy, particularly in Western countries, where concerns have been raised about potential political influence, academic freedom, and the alignment of these institutes' curricula with Chinese government perspectives. This has led some universities to reevaluate or close their partnerships with Confucius Institutes. Despite these challenges, Confucius Institutes continue to play a vital role in China's cultural outreach, representing a unique aspect of China's “soft power.” By enhancing its image abroad, these institutes not only foster cultural output but may also indirectly support China's economic goals, such as expanding trade relations and improving the country's global standing.

Cultural output in the literature often refers to the activities, products, and initiatives through which a nation projects its cultural identity, values, and traditions internationally. It encompasses a wide range of elements, including language, art, literature, media, education, and cultural exchange programs. Cultural output serves as a tool of soft power, enabling countries to foster positive perceptions, build relationships, and influence global attitudes and behaviors. Confucius Institutes are a tangible and structured form of China's cultural output, specifically designed to promote Chinese language, culture, and traditions abroad. As one of the most prominent and influential examples of China's cultural output, Confucius Institutes not only strengthen China's soft power but also support its economic objectives, such as fostering stronger trade relationships and enhancing its global standing.

In this paper, we examine the impact of cultural output on trade, using Confucius Institutes as a measure of China's cultural outreach. Through gravity regression estimation, we focus primarily on the effect of Confucius Institutes on China's exports. To ensure robustness, we extend the analysis to include imports as well as the combined effect on exports and imports. Additionally, we incorporate data on Confucius Institutes from previous periods and account for any new openings or closures within the current period. Recognizing that the establishment and removal of Confucius Institutes are not exogenous, as they are influenced by factors such as strategic geopolitical considerations, public sentiment, concerns about political influence, and academic freedom, we address potential endogeneity using an instrumental variables (IV) approach. This method strengthens the validity of our findings. Sector-level analysis is also conducted at a disaggregated level to capture more granular effects. In our mechanism analysis, we investigate whether cultural output influence trade by enhancing China's global image and prestige.

Our findings indicate that China's cultural output, as measured by Confucius Institutes, have a significantly positive impact on exports. This positive effect persists across robustness checks. Furthermore, when we incorporate the number of Confucius Institutes from prior periods, along with indicators for newly opened or closed institutes within the current period, our results remain consistent. Sector-level analyses at the disaggregate level yield similar outcomes. Our mechanism analysis confirms that cultural output facilitates trade by enhancing China's global image and prestige. The heterogeneous analysis reveals that the positive effects of cultural output are especially strong in the nations in Latin America and the Caribbean, East and South Asia, as well as in industrial or high-income countries, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) member states, and countries with shorter cultural distance from China. From a sectoral standpoint, we find that differentiated goods benefit significantly from cultural output.

This study advances our understanding of the relationship between culture and international trade by exploring how cultural output, specifically Confucius Institutes, influences trade flows. While traditional trade determinants such as economic size, distance, and trade agreements are well-studied, the role of cultural diplomacy remains underexplored. By focusing on CIs as a structured form of state-led cultural output, this study fills a critical gap, providing new insights into how cultural initiatives shape economic exchanges. Unlike prior studies that emphasize shared cultural or ethnic ties (Rauch and Trindade 2002), this paper examines deliberate, state-driven efforts to enhance cultural familiarity and reduce informational barriers. Mechanistic analysis reveals that cultural output improves a country's global image and prestige, facilitating greater trade. Using a gravity model, this study quantifies the trade-enhancing effects of CIs, contributing robust empirical evidence to the literature. Additionally, the research highlights the heterogeneous effects of cultural output across country characteristics (e.g., income levels, cultural distance) and product categories (e.g., differentiated goods), offering nuanced insights into how culture interacts with trade determinants. These findings suggest that cultural diplomacy serves as a strategic complement to traditional trade policies, providing policymakers with actionable strategies to strengthen trade relationships, particularly with high-income or culturally closer countries.

This paper contributes to multiple strands of literature. First, it aligns with research examining non-economic factors influencing international trade. While traditional determinants of bilateral trade—such as free trade agreements (Baier and Bergstrand 2007; Caliendo and Parro 2015; Baier et al. 2019), Generalized System of Preferences (Herz and Wagner 2011; Ornelas and Ritel 2020), common currency (Rose 2000), and World Trade Organization (WTO) membership (Rose 2004; Chang and Lee 2011)—are well-established in the literature, nontraditional and non-economic factors, including cultural and media influences, remain less explored. Some studies suggest that cultural elements can promote a country's exports and improve its welfare (Guiso et al. 2006, 2009; Chang et al. 2022). Confucius Institutes, as a structured and impactful form of cultural output, play a key role in increasing exposure to Chinese culture and enhancing China's image abroad. This increased familiarity with Chinese culture and perceived quality of Chinese products, facilitated by Confucius Institutes, likely encourages greater imports of Chinese goods (Chang et al. 2022). Importantly, Confucius Institutes represent a deliberate, state-driven cultural outreach rather than a result of long-term cultural or ethnic ties that are often emphasized in existing literature (Guiso et al. 2006, 2009). By focusing on these institutes—unique cultural entities established under Chinese government direction and with possible political implications—this paper adds to the literature on how state-led cultural output can influence bilateral trade dynamics.

Additionally, this paper contributes to the literature on China's globalization policy, particularly regarding the political dimensions underlying China's economic expansion. Numerous studies explore China's trade liberalization, reflecting its significant economic size and substantial trade volumes (Autor et al. 2016; Brandt et al. 2017). As a country with distinctive institutional, economic, and political characteristics, China's trade relations exhibit unique patterns. Research indicates that historical conflicts and ongoing political tensions can negatively affect China's trade relations, influencing both public sentiment and governmental stances (Fuchs and Klann 2013; Che et al. 2015). However, these adverse effects tend to be short-lived, underscoring China's sustained focus on economic development as a core policy objective (Du et al. 2017). Our paper shifts the focus to a positive influence on China's foreign trade: Confucius Institutes. These institutes, rarely discussed in prior studies, complement the literature on negative shocks affecting China's trade (Autor et al. 2013, 2019). In addition to Confucius Institutes, China has initiated ambitious global strategies to enhance its influence, including the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the Belt and Road Initiative, and the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (Gao et al. 2024). These initiatives, which China either leads or strongly advocates, have significant political dimensions. Enhancing international trade remains a central objective within these strategies. By employing a gravity model, we systematically quantify the impact of Confucius Institutes on China's foreign trade and examine the mechanisms underlying this effect, adding depth to the literature on China's international relations and trade dynamics.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the history and development of the Confucius Institutes. Section 3 outlines the empirical methods, data, and benchmark results. Section 4 discusses the mechanism analysis, while Section 5 presents the heterogeneous analysis. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2 History and Development of the Confucius Institutes

Confucius Institutes are nonprofit educational institutions established voluntarily by foreign organizations in collaboration with Chinese and foreign partners, adhering to principles of mutual respect, friendly consultation, and equality and mutual benefit. Their goal is to promote the international dissemination of the Chinese language, deepen global understanding of Chinese language and culture, and enhance educational and cultural exchanges between China and other countries. The collaborative ecosystem of Confucius Institutes is centered on the institutes themselves, with contributions from the Confucius Institute Headquarters, Chinese and foreign partner institutions, and a wide array of external collaborators. These participants jointly serve Confucius Institute students and global learners of Chinese, striving to build an extensive, tightly connected, and mutually beneficial global network and community of shared destiny.

The primary functions of Confucius Institutes include: offering Chinese language instruction and related research; providing education and research in other disciplines or fields using Chinese as the primary medium; training Chinese language teachers; developing Chinese language teaching resources; organizing cultural exchange activities between China and other countries; conducting examinations and certifications related to the Chinese language and culture; offering research and consulting services in areas such as Chinese education, culture, and economy; and undertaking other activities aligned with the mission of Confucius Institutes.

In June 2004, China began collaborating with foreign institutions to establish Confucius Institutes overseas. The agreements for the Tashkent State Institute of Oriental Studies Confucius Institute in Uzbekistan, the University of Maryland Confucius Institute in the United States, and the University of Nairobi Confucius Institute in Kenya were signed, marking the first Confucius Institutes in Asia, the Americas, and Africa, respectively. At the same time, the Seoul Confucius Institute in South Korea officially launched, becoming the first globally operational Confucius Institute. In March 2005, agreements for the Brussels Confucius Institute in Belgium and the University of Western Australia Confucius Institute were signed, representing the first Confucius Institutes in Europe and Oceania. In July 2006, the first Global Confucius Institute Conference was convened. In January of the following year, the Confucius Institute Headquarters was established, and in April of that year, the Headquarters Council, composed of representatives from both China and partner countries, was created.

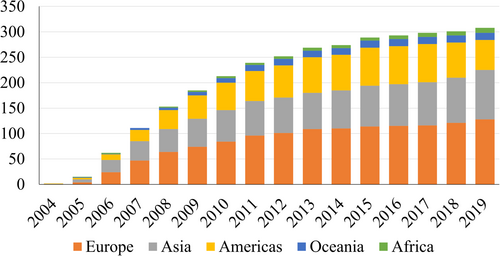

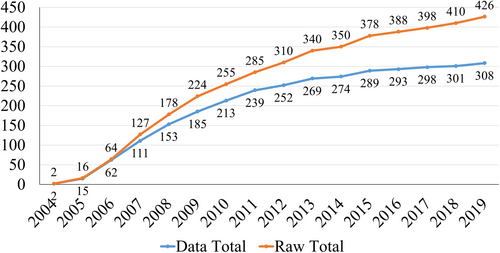

Due to the availability of trade data and proxy variables for bilateral trade costs, our study focuses on the period from 1990 to 2019. Figure 1 shows the trends in the total number of Confucius Institutes globally and within the sample used in this study from 1990 to 2019. We can observe that the two trends are consistent, and the total number of Confucius Institutes in the research sample accounts for the vast majority of the total in the original data set, making it highly representative. Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of Confucius Institutes across different continents during the same period. It can be seen that the number of Confucius Institutes in Europe, Asia, and the Americas dominates.

The development of Confucius Institutes continues to progress. According to the annual development report on the official website of Confucius Institutes, as of December 31, 2023, there were 496 Confucius Institutes worldwide, covering 160 countries and regions. These included 137 in Asia, 64 in Africa, 184 in Europe, 88 in the Americas, and 19 in Oceania. The institutes registered approximately 125,000 students and provided over 2.42 million hours of teaching services, offering approximately 40,000 Chinese language courses.

3 Empirical Analysis

3.1 Regression Specifications

We initially apply Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimation with Equation (1). To address potential issues with zero trade flows and heteroskedasticity, we also employ Poisson Pseudo-Maximum Likelihood (PPML) estimation using Equation (2). This approach is widely adopted in empirical trade research (Silva and Tenreyro 2006; Head and Mayer 2014).

In these equations, represents the GDP weighted exports from China to the destination country j in year t. This normalization is to handle the high dispersion of dependent variable and make the numerical algorithm converge efficiently (Chang et al. 2022; Silva and Tenreyro 2011). The variable denotes the number of Confucius Institutes in country j during year t, serving as a measure of China's cultural output in the destination country. Through this strategy of cultural output, China aims to bridge cultural gaps between countries. Confucius Institutes, which foster understanding of Chinese language and culture, also strengthen academic exchanges and higher education collaborations internationally. By promoting a more favorable image, these institutes may reduce biases and enhance China's influence in the global community, potentially stimulating economic activity between China and other countries. Given that can be zero in some cases, we apply the transformation to accommodate these instances. Additionally, we include the linear form of in robustness checks to assess the consistency of our results across alternative specifications.

The vector X includes both time-variant and time-invariant asymmetric trade cost proxies and the GDP (in logarithm) in the destination country, as detailed in Table 1, with summary statistics provided in Table 2. The time-variant trade cost proxies encompass factors such as the presence of a regional trade agreement between countries, whether the importing country offers a Generalized System of Preferences, the use of a common currency, and any colonial relationships where either the exporting or importing country is currently a colonizer. The time-invariant trade cost proxies include linguistic and historical ties: whether the two countries share the same official or primary language, whether at least 9% of the population in both countries speaks a common language, shared colonizers after 1945, common legal origins, and prolonged periods of shared statehood or administrative unity. Additionally, geographic and political factors are considered, such as whether the two countries are contiguous, whether both are island nations or landlocked, and the logarithmic population-weighted bilateral distance (in kilometers).

| Variables | Definition |

|---|---|

| GDP weighted disaggregate level trade flows | |

| GDP weighted aggregate level trade flows | |

| Number of Confucius Institutes | |

| GDP of the destination country (in million US dollars) | |

| Whether a regional trade agreement is in force between countries | |

| Whether the importing country offers a Generalized System of Preference (GSP) to the exporting country | |

| Whether two countries use a common currency | |

| Whether the exporting country is currently a colonizer of the importing country | |

| Whether the importing country is currently a colonizer of the exporting country | |

| Whether two countries use the same language as the official or primary language | |

| Whether the same language is spoken by at least 9% of the population in both countries | |

| Whether two countries have had a common colonizer after 1945 | |

| Whether two countries have a common legal origin | |

| Whether two countries were or are the same state or the same administrative entity for a long period of time | |

| Whether the exporting country has ever been a colonizer of the importing country | |

| Whether the importing country has ever been a colonizer of the exporting country | |

| Whether two countries are contiguous | |

| Whether both countries are island countries | |

| Whether both countries are landlocked | |

| Logarithm of population-weighted bilateral distance (km) |

- Note: This table provides the definition of dependent variables, number of Confucius Institutes, each of the (asymmetric) trade cost proxies and GDP. These trade cost proxies include both time-variant and time-invariant variables.

| Categories | Variable | Obs. | Mean | Std. dev. | Min | Max | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | 6,085,717 | 1.2635 | 112.5851 | 5.33e − 11 | 114,840.6 | j, s, t | |

| 2886 | 2663.519 | 26,204.07 | 0.0534 | 833,753.9 | j, t | ||

| Cultural output | 2886 | 0.3405 | 0.7001 | 0 | 3.7377 | j, t | |

| 2677 | 0.3327 | 0.6920 | 0 | 3.7377 | j, t | ||

| 2886 | 0.0703 | 0.2558 | 0 | 1 | j, t | ||

| 2886 | 0.0028 | 0.05259 | 0 | 1 | j, t | ||

| GDP and trade cost proxies | 2886 | 444,445.7 | 1,517,430 | 1.7023 | 2.14e + 07 | j, t | |

| 2886 | 0.0994 | 0.2993 | 0 | 1 | j, t | ||

| 2886 | 0.1448 | 0.3520 | 0 | 1 | j, t | ||

| 2886 | 0.0024 | 0.0492 | 0 | 1 | j, t | ||

| 2886 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | j, t | ||

| 2886 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | j, t | ||

| 98 | 0.0102 | 0.1010 | 0 | 1 | j | ||

| 98 | 0.0102 | 0.1010 | 0 | 1 | j | ||

| 98 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | j | ||

| 98 | 0.3265 | 0.4714 | 0 | 1 | j | ||

| 98 | 0.0102 | 0.1010 | 0 | 1 | j | ||

| 98 | 0.0102 | 0.1010 | 0 | 1 | j | ||

| 98 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | j | ||

| 98 | 0.0918 | 0.2903 | 0 | 1 | j | ||

| 98 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | j | ||

| 98 | 0.0204 | 0.1421 | 0 | 1 | j | ||

| 98 | 9.0084 | 0.4891 | 6.9257 | 9.8291 | j |

- Note: This table provides the summary statistics of the variables we use in the benchmark regressions.

In our benchmark analysis, we focus exclusively on China's exports, designating China as the origin country. Consequently, we include destination-country fixed effects () and year fixed effects () in the estimation. Since the origin country is solely China in this model, there is no need to control for origin-country-related fixed effects. This setup simplifies the analysis by reducing the dimensions from ijt or ij to jt or j dimensions. For the robustness checks, when examining China's imports and the combined effect of China's exports and imports, we similarly omit fixed effects related to China. As a result, trade cost proxies are adjusted to the origin/partner country level or origin-year/partner-year level accordingly.

3.2 Data

Our data set consists of three main components. First, trade flow data primarily come from the Centre d'Études Prospectives et d'Informations Internationales (CEPII)1 and are supplemented with data from the World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS). Second, data on Confucius Institutes are manually collected from official websites,2 with additional verification and supplementation from Wikipedia. Third, trade cost proxies are compiled from multiple sources, with the primary variables drawn from CEPII's Gravity and GeoDist datasets, unless otherwise specified below. Additionally, GDP data are obtained from the World Development Indicators (WDI) and CEPII.

The variables not primarily sourced from CEPII include the following: the regional trade agreement (RTA) indicator, derived from the Economic Integration Agreements Database (April 2017) by Scott Baier and Jeffrey Bergstrand,3 and supplemented by the World Trade Organization (WTO) Regional Trade Agreements Database4 to address any missing data. Data on Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) treatment was obtained from the same Economic Integration Agreements Database, with gaps filled using the WTO's Database on Preferential Trade Agreements5 and, if still incomplete, from the United Nation Trade and Development's (UNCTAD) “Generalized System of Preferences: List of Beneficiary Countries.”6 Notably, UNCTAD's GSP data is updated intermittently, with available years including 2001, 2005, 2006, 2008, 2009, 2011, and 2015. Additional trade cost indicators include the common currency variable from de Sousa,7 supplemented by CEPII's Gravity data set. Legal origin data was compiled from CEPII, with supplementary information from La Porta (1999, 2008) and the Central Intelligence Agency's (CIA) World Factbook,8 to create a common legal origin indicator (equal to one if two countries share a legal origin). Information on landlocked or island status of country pairs comes from Andrew Rose,9 further corroborated by the CIA World Factbook.

Our benchmark analysis includes 2,886 observations at the destination-origin-year level, covering 98 destination countries from 1990 to 2019, with China consistently as the exporter or origin country. For robustness checks at the disaggregated level, the sample expands significantly to 6,085,717 observations at the destination-origin-HS6-sector-year level, with China remaining as the exporter or origin country.

3.3 Benchmark Results

Table 3 presents the benchmark results on the impact of cultural outputs on China's exports, using data from 1990 to 2019. Throughout Columns (1)–(9), both time-variant and time-invariant trade cost proxies and the GDP (in logarithm) of destination country are consistently controlled to isolate the effect of cultural output on trade. Columns (1) through (4) report results from OLS estimation, while Columns (5) through (9) show results obtained using PPML estimation. Specifically, Columns (1) and (5) do not include any fixed effects; Columns (2) and (6) introduce destination-country fixed effects; Columns (3) and (7) add year fixed effects; and Columns (4), (8), and (9) incorporate both destination-country and year fixed effects. In addition, we also provide the PPML result by using the number of Confucius Institutes in the linear form in Column (9). This structured approach allows us to assess the stability of the results under different model specifications.

| Method | OLS | PPML | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dep. var. | |||||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| 0.765*** | 0.729*** | 0.0719 | −0.0749 | 0.290* | 3.623*** | −0.128 | 0.182** | ||

| (0.132) | (0.151) | (0.0753) | (0.0629) | (0.170) | (1.237) | (0.152) | (0.0850) | ||

| 0.0226** | |||||||||

| (0.0109) | |||||||||

| ln GDP and Trade cost proxies | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||

| Obs. | 2886 | 2884 | 2886 | 2884 | 2886 | 2884 | 2886 | 2884 | 2884 |

| 0.361 | 0.526 | 0.844 | 0.951 | ||||||

- Note: The table shows the benchmark results of the impact of Confucius Institutes on China's exports, using the data from 1990 to 2019. represents GDP weighted exports from China to country j in year t. Time-variant and time-invariant trade cost proxies and GDP of the destination country (in logarithm) are controlled across all Columns (1)–(9). Columns (1)–(4) show the results by using OLS and Columns (5)–(9) show the results by using PPML. In Columns (1)–(8), the number of Confucius Institutes is presented in logarithmic form, whereas in Column (9), it is expressed in linear form. In Columns (1) and (5), fixed effects are not controlled. In Columns (2) and (6), destination country fixed effects are controlled. In Columns (3) and (7), year fixed effects are controlled. In Columns (4), (8), and (9), both destination country and year fixed effects are controlled. Standard errors, clustered at the destination country level, are reported in parentheses. The symbols ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

The number of Confucius Institutes (both in logarithmic terms and in linear form), which serves as a proxy for China's cultural output, consistently exhibits a significantly positive effect on China's exports across most fixed-effects specifications. Exceptions are found in Columns (3) and (4) of the OLS results and Column (7) of the PPML results with only the time fixed effects, where the effect loses significance. This outcome might suggest some sensitivity to the choice of estimation method, particularly since OLS does not account for potential biases related to zero trade flows and heteroskedasticity. Given that PPML is designed to handle these issues by appropriately managing zero trade flows and heteroskedasticity in trade data, we prioritize the PPML results, identifying Column (8) with the most comprehensive fixed effects as our benchmark model.

According to the benchmark model (PPML with both destination-country and year fixed effects), the results indicate a clear positive association between cultural output—measured by the number of Confucius Institutes—and China's exports. Specifically, a one percent increase in the cultural output strength, as represented by the number of Confucius Institutes, correlates with a 0.182 percent increase in China's exports to the destination country within the same period. This finding suggests that cultural outreach, through Confucius Institutes, plays a meaningful role in promoting Chinese exports by fostering greater awareness, understanding, and potentially favorable perceptions of China among citizens and institutions in the host country.

These results underline the potential of cultural diplomacy to act as a soft power mechanism that complements traditional trade policies. The establishment of Confucius Institutes may facilitate closer cultural ties, reduce informational and cultural barriers, and create a more receptive environment for Chinese goods and services. The consistency of these findings across different model specifications further strengthens the argument that cultural output, as a form of soft power, can positively impact economic outcomes by building bridges that extend beyond purely economic factors. This benchmark analysis offers important implications for policymakers, suggesting that investments in cultural diplomacy can yield economic dividends by enhancing China's global trade footprint.

3.4 Robustness Checks

To validate the robustness of our benchmark results, we perform several checks: (1) addressing the endogeneity issue; (2) adjusting the research period; (3) employing alternative measures of cultural output; (4) focusing on China's imports or the combined effect of exports and imports; and (5) conducting disaggregated regressions that incorporate sectoral dimensions.

Addressing the endogeneity issue. To address potential endogeneity concerns, Table 4 presents results using IV estimation. Specifically, we employ two instruments: (1) the number of Confucius Institutes established in the destination country 4 years prior (), and (2) the interaction between the probability of a destination country hosting Confucius Institutes () and the total number of Confucius Institutes globally in a given year (), defined as . The probability of hosting Confucius Institutes is calculated as the proportion of years during the study period that a destination country has hosted Confucius Institutes. The total number of Confucius Institutes reflects China's capacity to establish Institutes in a given year. This two-part interaction approach is well-established and empirically validated in the literature on international trade and aid (e.g., Dreher et al. 2019, 2021; Dreher and Langlotz 2020; Nunn and Qian 2014). Conceptually, using the interaction term as an instrument parallels a difference-in-differences (DiD) strategy. The first stage estimates compare the establishment of Confucius Institutes in countries that frequently host them to those that rarely do, during periods of high global activity in establishing Institutes versus low activity. The reduced-form estimates extend this comparison, substituting trade flows as the dependent variable. Unlike the traditional DiD approach, our method treats the “treatment” variable (the number of Confucius Institutes) as continuous, allowing for a more nuanced analysis.

| and | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-stage | IV PPML | First-stage | IV PPML | First-stage | IV PPML | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| 0.210*** | 0.635*** | 0.164*** | ||||

| (0.0808) | (0.225) | (0.0614) | ||||

| 0.697*** | 0.454*** | |||||

| (0.0308) | (0.0412) | |||||

| 0.0163*** | 0.00951*** | |||||

| (0.00177) | (0.00112) | |||||

| ln GDP and Trade cost proxies | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Obs. | 2211 | 2215 | 2884 | 2886 | 2211 | 2215 |

| Hansen J-statistic | 0.4580 | |||||

| p-value | 0.4985 | |||||

| First-stage F-statistic | 513.08 | 84.16 | 190.49 | |||

- Note: The table shows Instrumental Variables (IV) estimation results. Columns (1) and (2) show the results by using . Columns (3) and (4) show the results by using . Columns (5) and (6) show the results by using both and . Columns (1), (3), and (5) show the first-stage results, while Columns (2), (4), and (6) show the second-stage results by using PPML. Time-variant and time-invariant trade cost proxies, GDP of the destination country (in logarithm), destination country and year fixed effects are controlled from Columns (1) to (6). Standard errors, clustered at the destination country level, are reported in parentheses. The symbols ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

These two instruments are intuitively positively correlated with the number of Confucius Institutes, satisfying the relevance requirement. Furthermore, the 4-year lagged value and the interaction term combining the probability of establishing Confucius Institutes and the total number of Institutes are unlikely to correlate with the error term or directly influence current trade flows. This is particularly true after accounting for country and time fixed effects, thereby fulfilling the exclusion restriction (Nunn and Qian 2014). Columns (1) and (2) show the results by using . Columns (3) and (4) show the results by using . Columns (5) and (6) show the results by using both and . The first-stage results consistently show significant positive relationships, with F-statistics well above the critical thresholds. Similarly, the second-stage results confirm significantly positive effects on exports. The Hansen J-statistic alleviates concerns about over-identification. In summary, the IV estimation results reinforce the robustness of our baseline findings, demonstrating that the number of Confucius Institutes significantly promotes China's exports.

Adjusting the research period. In Table 5, we re-estimate the regressions using data from 1980 to 2019, controlling for both time-variant and time-invariant trade cost proxies across Columns (1)–(8). Columns (1)–(4) present results from OLS estimation, while Columns (5)–(8) show results from PPML estimation. In Columns (1) and (5), no fixed effects are applied; Columns (2) and (6) control for destination-country fixed effects; Columns (3) and (7) include year fixed effects; and Columns (4) and (8) incorporate both destination-country and year fixed effects. The number of Confucius Institutes, representing cultural output, continues to exhibit a significantly positive effect on China's exports across most fixed-effects specifications, with the exceptions of Columns (3), (4), and (7). The effect sizes remain consistent with those reported in Table 3.

| Method | OLS | PPML | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dep. var. | ||||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| 0.794*** | 0.731*** | 0.0800 | −0.0910 | 0.292* | 3.611*** | −0.127 | 0.184** | |

| (0.137) | (0.154) | (0.0755) | (0.0687) | (0.170) | (1.207) | (0.151) | (0.0883) | |

| ln GDP and Trade cost proxies | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||

| Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||

| Obs. | 2999 | 2996 | 2999 | 2996 | 2999 | 2996 | 2999 | 2996 |

| 0.365 | 0.530 | 0.837 | 0.942 | |||||

- Note: The table shows the benchmark results of the impact of Confucius Institutes on China's exports, using the data from 1980 to 2019. represents GDP weighted exports from China to country j in year t. Time-variant and time-invariant trade cost proxies and GDP of the destination country (in logarithm) are controlled across all Columns (1)−(8). Columns (1)−(4) show the results by using OLS and Columns (5)−(8) show the results by using PPML. In Columns (1) and (5), fixed effects are not controlled. In Columns (2) and (6), destination country fixed effects are controlled. In Columns (3) and (7), year fixed effects are controlled. In Columns (4) and (8), both destination country and year fixed effects are controlled. Standard errors, clustered at the destination country level, are reported in parentheses. The symbols ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Employing alternative measures of cultural output. In Table 6, we incorporate lagged values of Confucius Institutes (), a dummy variable for newly established Institutes in the current period (), and a dummy variable indicating any closures of Confucius Institutes in the current period () to capture China's cultural output in a more dynamic way. Columns (1)–(3) cover the period from 1990 to 2019, while Columns (4)–(6) cover 1980–2019. The results demonstrate that cultural output from the previous year has a positive and significant impact on China's exports, indicating a sustained effect of China's cultural initiatives. In contrast, newly established Institutes and reductions in the number of Confucius Institutes do not show significant effects on trade. The insignificant coefficients for and suggest that the immediate establishment or closure of Confucius Institutes has a limited influence on China's exports. These findings imply that the trade-enhancing effects of Confucius Institutes require time to materialize, as they depend on the gradual development of cultural familiarity and trust. Furthermore, the cumulative number of Confucius Institutes appears to have a more substantial and enduring impact, as reflected in the estimates identified in the benchmark analysis. This highlights the importance of sustained and consistent cultural outreach efforts in achieving meaningful economic outcomes.

| Dep. var. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | 1990–2019 | 1980–2019 | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| 0.444*** | 0.372*** | 0.445*** | 0.443*** | 0.372*** | 0.444*** | |

| (0.117) | (0.0866) | (0.117) | (0.117) | (0.0866) | (0.117) | |

| 0.0417 | 0.0418 | 0.0415 | 0.0416 | |||

| (0.0320) | (0.0320) | (0.0320) | (0.0321) | |||

| 0.0212 | 0.0234 | 0.0212 | 0.0233 | |||

| (0.0371) | (0.0376) | (0.0371) | (0.0376) | |||

| ln GDP and Trade cost proxies | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Obs. | 2813 | 2808 | 2813 | 2808 | 2877 | 2872 |

- Note: The table shows the results of impact of Confucius Institutes on China's exports by using PPML. represents GDP weighted exports from China to country j in year t. Time-variant and time-invariant trade cost proxies, GDP of the destination country (in logarithm), destination country and year fixed effects are controlled from Columns (1)–(6). The research period is from 1990 to 2019 in Columns (1)–(3) and from 1980 to 2019 in Columns (4)–(6). In Columns (1) and (3), (2) and (4), and (3) and (6), cultural output are represented by and , and , and with both and , respectively. Standard errors, clustered at the destination country level, are reported in parentheses. The symbols ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Focusing on China's imports or the combined effect of exports and imports. Tables 7 and 8 present the impact of cultural output on China's imports and the combination of China's exports and imports, using PPML across different time periods and fixed-effect specifications. Consistent with our benchmark findings, cultural output—represented by the number of Confucius Institutes (in logarithmic terms)—maintains a positive, significant impact on both China's imports and the combined effect of China's exports and imports. Additionally, In Table 7, China is the destination country, while the trade partner is the origin country (i). In Table 8, where exports and imports are combined, we assign the partner country as country p.

| Dep. var. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | 1990–2019 | 1980–2019 | ||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| 0.668*** | 3.060*** | 0.185 | 0.192*** | 0.670*** | 3.070*** | 0.186 | 0.194*** | |

| (0.235) | (0.980) | (0.201) | (0.0666) | (0.235) | (0.976) | (0.201) | (0.0687) | |

| ln GDP and Trade cost proxies | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||

| Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||

| Obs. | 2813 | 2808 | 2813 | 2808 | 2877 | 2872 | 2877 | 2872 |

- Note: The table shows the results of the impact of cultural output on China's imports by using PPML. is defined as the GDP weighted imports to China from country i in year t. Time-variant and time-invariant trade cost proxies, GDP of the origin country (in logarithm) are controlled from Columns (1) to (8). The research period is from 1990 to 2019 in Columns (1)–(4) and from 1980 to 2019 in Columns (5)–(8). In Columns (1) and (5), fixed effects are not controlled. In Columns (2) and (6), origin country fixed effects are controlled. In Columns (3) and (7), year fixed effects are controlled. In Columns (4) and (8), both origin country and year fixed effects are controlled. Standard errors, clustered at the origin country level, are reported in parentheses. The symbols ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

| Dep. var. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | 1990–2019 | 1980–2019 | ||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| 0.453*** | 3.175*** | 0.00249 | 0.180** | 0.455*** | 3.180*** | 0.00406 | 0.183** | |

| (0.176) | (1.102) | (0.141) | (0.0738) | (0.176) | (1.083) | (0.141) | (0.0754) | |

| ln GDP and Trade cost proxies | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||

| Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||

| Obs. | 2972 | 2969 | 2972 | 2969 | 3089 | 3087 | 3089 | 3087 |

- Note: The table shows the results of the impact of cultural output on the combination of China's exports and imports by using PPML. is defined as the GDP weighted combination of exports and imports between China and partner country p in year t. Time-variant and time-invariant trade cost proxies and GDP of the partner country (in logarithm) are controlled from Columns (1) to (8). The research period is from 1990 to 2019 in Columns (1)–(4) and from 1980 to 2019 in Columns (5)–(8). In Columns (1) and (5), fixed effects are not controlled. In Columns (2) and (6), partner country fixed effects are controlled. In Columns (3) and (7), year fixed effects are controlled. In Columns (4) and (8), both partner country and year fixed effects are controlled. Standard errors, clustered at the partner country level, are reported in parentheses. The symbols ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Disaggregated-level regressions. To complement the aggregate analysis, we conduct regressions on China's exports at the disaggregated level, using origin-destination-HS6-sector–year data. The results are presented in Tables 9 and 10. In Table 9, cultural output is represented by the number of Confucius Institutes (in logarithmic terms), consistent with the benchmark model. In Table 10, we introduce the tariff rate as an additional control for trade policies at the disaggregated level. The findings remain consistent with the aggregate-level benchmark when the most complete combinations of fixed effects are included in Columns (8) and (9) in both tables, confirming that cultural output exerts a significant positive impact on China's exports.

| Dep. var. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| 0.312* | 3.604*** | −0.128 | 0.308* | 0.182*** | 3.616*** | −0.128 | 0.193** | 0.183** | |

| (0.174) | (1.219) | (0.142) | (0.172) | (0.0691) | (1.221) | (0.148) | (0.0862) | (0.0733) | |

| ln GDP and Trade cost proxies | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||

| Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||

| Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||

| Y | |||||||||

| Obs. | 6,027,438 | 6,027,438 | 6,027,438 | 6,027,436 | 6,027,438 | 6,027,436 | 6,027,436 | 6,027,436 | 6,023,061 |

- Note: The table shows the results of the impact of cultural output on China's exports by using PPML and data from 1990 to 2019 at importer-sector-year level. is defined as the GDP weighted exports from China to country j in sector s and year t. Time-variant and time-invariant trade cost proxies and GDP of the destination country (in logarithm) are controlled from Columns (1) to (9). Different combinations of the fixed effects are included from Columns (1) to (9). Standard errors, clustered at the destination country level, are reported in parentheses. The symbols ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

| Dep. var. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| 0.176 | 13.14*** | −0.562*** | 0.151 | 0.421*** | 12.95*** | −0.584*** | 0.441*** | 0.441** | |

| (0.250) | (4.726) | (0.174) | (0.232) | (0.138) | (4.570) | (0.174) | (0.166) | (0.177) | |

| −4.232*** | −0.188 | 0.832* | −6.360*** | 1.100** | −1.643 | 0.135 | 0.443 | 0.458 | |

| (1.484) | (0.957) | (0.498) | (2.039) | (0.444) | (1.346) | (0.846) | (0.823) | (0.879) | |

| ln GDP and Trade cost proxies | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||

| Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||

| Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||

| Y | |||||||||

| Obs. | 3,112,543 | 3,112,543 | 3,112,543 | 3,112,535 | 3,112,543 | 3,112,535 | 3,112,535 | 3,112,535 | 3,105,105 |

- Note: The table shows the results of the impact of cultural output on China's exports by using PPML and data from 1990 to 2019 at importer-sector-year level. is defined as the GDP weighted exports from China to country j in sector s and year t. Time-variant and time-invariant trade cost proxies and GDP of the destination country (in logarithm) are controlled from Columns (1) to (9). Different combinations of the fixed effects are included from Columns (1) to (9). Standard errors, clustered at the destination country level, are reported in parentheses. The symbols ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

4 Mechanism Analysis

In this section, we explore the mechanisms through which cultural output influences trade, focusing on the roles of country image and Google Trends.

Following Chang et al. (2022), data on country image is sourced from the BBC World Service Poll, conducted annually from 2005 to 2014 and in 2017 by GlobeScan and the Program on International Policy Attitudes (PIPA). Each survey round sampled approximately 1,000 respondents per evaluating country, using either face-to-face or phone interviews. Respondents were asked whether they viewed each evaluated country as having a “mainly positive” or “mainly negative” global influence. Additional response options included “depends,” “neither, neutral,” and “DK/NA (don't know or no answer),” though these options were unprompted. We classify “depends” and “neither, neutral” responses as “neutral.” For analysis, we use the fraction of “mainly negative” responses () as an inverse measure of country image, with higher values indicating a more negative perception of China in the trade partner country. Data on Google Trends, reflecting search interest in China with the keyword “Confucius Institute,” was manually collected from Google for the period 2004–2019.10

Table 11 presents the mechanism analysis of the benchmark results, examining the effect of cultural output on China's country image and Google search interest. Columns (1) and (2) display OLS results. Columns (3) and (4) present PPML results. Columns (5)–(7) show the Tobit results. Findings indicate that cultural output significantly reduces the proportion of respondents holding a “mainly negative” view of China, suggesting that increased cultural output enhances China's exports by improving its international image and reducing negative perceptions. Additionally, cultural output significantly raises the frequency of Google searches for “Confucius Institute.” Together, these results indicate that cultural output fosters trade by boosting China's image and prestige abroad.

| Method | OLS | PPML | Tobit | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dep. var. | |||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| −0.175** | 2.398*** | −0.153** | 0.896** | −4.581** | 148.1** | 2.279*** | |

| (0.0620) | (0.274) | (0.0612) | (0.358) | (1.819) | (65.94) | (0.354) | |

| ln GDP and Trade cost proxies | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Obs. | 173 | 100 | 173 | 661 | 178 | 957 | 132 |

| 0.794 | 0.892 | ||||||

- Note: The table shows the effects of cultural output on China's country image and Google trend in the destination countries. The research period is from 1990 to 2019. Time-variant and time-invariant trade cost proxies, GDP of the destination country (in logarithm), destination country and year fixed effects are controlled from Columns (1) to (7). In Columns (1) and (2), OLS is applied. In Columns (3) and (4), PPML is applied. In Columns (5)–(7), Tobit is applied. Standard errors, clustered at the destination country level, are reported in parentheses. The symbols ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

5 Heterogeneous Analysis

In this section, we conduct a series of heterogeneous analyses to assess the effects of cultural output on trade across various dimensions, including regions, Cold War alliances, income groups, cultural distance categories, and sector classifications. Sector categories are defined based on the Broad Economic Categories (BEC), which classifies goods by type, and the Rauch (1999) classification, which categorizes goods according to their degree of heterogeneity.

Regional analysis. Table 12 presents the effects of cultural output on China's exports across various regions and groups: the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA), East and South Asia (ESA), Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), and other regions. The results indicate that cultural output has a relatively stronger and statistically significant positive effect on China's exports to ESA and LAC countries. In contrast, the effects are found to be statistically insignificant for other regions. These findings suggest that the impact of cultural output, as measured by Confucius Institutes, varies significantly across regions, with ESA and LAC emerging as key areas where cultural outreach yields meaningful trade benefits. This regional heterogeneity may reflect differences in cultural receptiveness, trade potential, or the alignment of cultural diplomacy efforts with economic opportunities in these areas.

| Dep. var. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regions | OECD | EECA | ESA | LAC | MENA | SSA | Others | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (9) | ||

| 0.146 | 0.0145 | 0.161*** | 0.384*** | −0.0721 | 0.345 | −0.222 | ||

| (0.0935) | (0.174) | (0.0555) | (0.0583) | (0.136) | (0.226) | (0.429) | ||

| ln GDP and Trade cost proxies | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| Obs. | 646 | 240 | 426 | 524 | 341 | 409 | 276 | |

- Note: The table shows the heterogeneous analysis of the impact of cultural output on China's exports by using the data from 1990 to 2019 across different regions. is defined as the GDP weighted exports from China to country j in year t. Time-variant and time-invariant trade cost proxies, GDP of the destination country (in logarithm), destination country, and year fixed effects are controlled from Columns (1) to (9). Standard errors, clustered at the destination country level, are reported in parentheses. The symbols ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Cold War alliances, income groups, and cultural distance. Table 13 presents a heterogeneous analysis across additional categories at the aggregate level. Columns (1) and (2) compare North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and non-NATO countries. During the Cold War, countries were classified into NATO, Warsaw Pact (WP), and other groups. Given that our study period begins in 1990, only a year before the dissolution of the WP in 1991, a direct comparison between WP and NATO is not feasible due to limited WP representation in the sample. The results indicate that NATO countries experience a stronger impact of cultural output on trade than non-NATO countries. Columns (3) and (4) separate countries into industrial and nonindustrial categories, using definitions by Subramanian and Wei (2007), supplemented by World Bank high-income classifications. Columns (5)–(7) further categorize countries by World Bank income levels (high, middle, and low). The findings reveal that cultural output has a more substantial effect in industrial and high-income countries, with negative effects observed for low-income countries. This may be attributed to China's foreign investment and aid replacing exports in less-developed regions, as previously mentioned. Columns (8) and (9) categorize countries by their cultural distance from China, using Hofstede's cultural distance indices (Hofstede 2011). The results show that the positive effect of cultural output is stronger in countries with shorter cultural distance from China. This may be because trade with culturally proximate countries can be better facilitated through existing connections. These findings underscore that cultural output activities, like the establishment of Confucius Institutes, can effectively take advantage of the shorter cultural distance in fostering trade.

| Dep. var. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cold War | Industrial or not | Income groups | Culture distance | ||||||

| NATO | None-NATO | Industrial | None-industrial | High | Middle | Low | Shorter | Longer | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| 0.199* | 0.177* | 0.220*** | −0.0638 | 0.225*** | −0.0322 | −0.339** | 0.176*** | 0.155 | |

| (0.103) | (0.0962) | (0.0685) | (0.0661) | (0.0737) | (0.0600) | (0.142) | (0.0605) | (0.115) | |

| ln GDP and Trade cost proxies | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Obs. | 626 | 2257 | 1160 | 1722 | 1079 | 1281 | 516 | 870 | 815 |

- Note: The table shows the heterogeneous analysis of the impact of cultural output on China's exports by using PPML and data from 1990 to 2019 in terms of the camps in Cold War, whether this country is industrial or not, incomes groups, and culture distance. is defined as the GDP weighted exports from China to country j in year t. Time-variant and time-invariant trade cost proxies, GDP of the destination country (in logarithm), destination country and year fixed effects are controlled from Columns (1) to (9). Standard errors, clustered at the destination country level, are reported in parentheses. The symbols ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Sector-specific analysis. We also conduct a disaggregated analysis by sector in Tables 14 and 15. Table 14 employs the Broad Economic Categories (BEC) classification from UN Trade Statistics to divide sectors into consumption goods (CONS), capital goods (CAP), and intermediate goods (INT). The results indicate a stronger positive effect of cultural output on consumption goods and intermediate goods, with the effect being most pronounced for consumption goods. This aligns with findings in the literature suggesting that country image primarily enhances bilateral trade through consumer perceptions (Chang et al. 2022). Additionally, we assess sector heterogeneity following Rauch (1999), categorizing products into differentiated sectors (higher heterogeneity), reference-priced products, and products traded on organized exchanges (with the latter two both considered homogeneous sectors). The findings indicate that cultural output has a more pronounced positive effect in differentiated sectors, while effects in homogeneous sectors—particularly those traded on organized exchanges—are either insignificant or negative. This may be due to the influence of specialized traders and centralized price information in these sectors, which are less susceptible to cultural output shocks. In some instances, increased trade in differentiated products may even crowd out trade in products traded on organized exchanges. Table 15 provides a robustness check, confirming similar results across different fixed-effect combinations.

| Method | PPML | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dep. var. | |||||||||

| BEC sectors | Rauch (1999): Conservative classification | Rauch (1999): Liberal classification | |||||||

| CAP | INT | CONS | Dif. | Ref. | Org. | Dif. | Ref. | Org. | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| 0.167 | 0.153* | 0.449*** | 0.273*** | 0.0971 | 0.241 | 0.274*** | 0.157* | 0.0167 | |

| (0.152) | (0.0801) | (0.158) | (0.0895) | (0.121) | (0.355) | (0.0888) | (0.0893) | (0.337) | |

| ln GDP and Trade cost proxies | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Obs. | 792,634 | 3,147,892 | 1,347,664 | 171,418 | 65,552 | 18,701 | 167,819 | 59,831 | 28,023 |

- Note: The table shows the heterogeneous analysis of the impact of cultural output on China's exports by using the data from 1990 to 2019 in terms of the BEC categories and sector categories by Rauch (1999). is defined as the GDP weighted exports from China to country j in sector s and year t. Time-variant and time-invariant trade cost proxies, GDP of the destination country (in logarithm), destination country and year fixed effects are controlled from Columns (1) to (9). Standard errors, clustered at the destination country level, are reported in parentheses. The symbols ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

| Dep. var. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEC sectors | Rauch (1999): Conservative classification | Rauch (1999): Liberal classification | |||||||

| CAP | INT | CONS | Dif. | Ref. | Org. | Dif. | Ref. | Org. | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| 0.135 | 0.150** | 0.451*** | 0.268*** | 0.0624 | 0.0166 | 0.270*** | 0.129 | −0.0647 | |

| (0.156) | (0.0759) | (0.145) | (0.0888) | (0.121) | (0.490) | (0.0888) | (0.0824) | (0.288) | |

| ln GDP and trade cost proxies | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Obs. | 792,388 | 3,146,274 | 1,347,175 | 171,348 | 65,465 | 18,611 | 167,756 | 59,754 | 27,916 |

- Notes: The table shows the heterogeneous analysis of the impact of cultural output on China's exports by using PPML and data from 1990 to 2019 in terms of the BEC categories and sector categories by Rauch (1999). is defined as the GDP weighted exports from China to country j in sector s and year t. Time-variant and time-invariant trade cost proxies, GDP of the destination country (in logarithm), destination country and year fixed effects are controlled from Columns (1) to (9). Standard errors, clustered at the destination country level, are reported in parentheses. The symbols ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

6 Conclusion

In this paper, we examine the effects of cultural output on trade, using the number of Confucius Institutes as a proxy for China's cultural outreach and focusing primarily on China's exports in our benchmark analysis. Our findings indicate that China's cultural output has a significantly positive impact on exports. Robustness checks further reveal that this positive effect persists when examining imports and the combined effect of exports and imports. Moreover, our analysis remains consistent when using lagged values of Confucius Institutes, as well as in sector-level analyses at the disaggregated level.

Our mechanism analysis shows that cultural output influences trade by improving China's global image and enhancing its prestige. The heterogeneous analysis indicates that these positive effects are especially strong in Latin America and the Caribbean, East and South Asia, as well as in industrialized and high-income countries, NATO member states, and countries with shorter cultural distance from China. From a sectoral perspective, we find that differentiated goods are significantly more affected by cultural output.

These findings suggest that cultural output plays a vital role in enhancing trade by boosting a country's image and prestige. The effects are particularly pronounced in trade with developed countries and in differentiated sectors, potentially elevating China's role in global value chains and strengthening its competitiveness internationally.

Author Contributions

Renjing Chen: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Wei Jin: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Tangrui Yang: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Ethics Statement

Informed consent was not required for this study because this study does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors and is based on publicly available data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Endnotes

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data associated with our study has not been deposited into a publicly available repository but will be made available on request.