Can Central Bank Communication Guide Individuals' Expectations About the Macroeconomy? Evidence From a Randomized Information Experiment in China

ABSTRACT

Communication with the market to guide public expectations has become a pivotal monetary policy instrument for central banks worldwide. Therefore, assessing the efficacy of communication in influencing personal expectations is essential for central banks. To examine the effectiveness of communication by the People's Bank of China (PBC), we conduct a randomized experiment in which subjects receive excerpts from China's Monetary Policy Implementation Report (MPIR) for the third quarter of 2022 as information interventions. This study exploits the exogenous variation generated by the treatment to explore how central bank communication influences individuals' expectations regarding the macroeconomy. The key findings are as follows: First, positive communication from the central bank can steer individuals' expectations about the likelihood of a recession in line with the central bank's objectives, and this effect is more pronounced among those who read financial news less frequently. Second, clear and specific retrospective communication is more effective in guiding expectations about the macroeconomy than vague and complex forward-looking communication. Third, PBC communication affects individuals' consumption plans, supporting the central bank's economic growth objectives.

1 Introduction

Following the 2008 financial crisis, conventional monetary policy in advanced economies has encountered significant obstacles, prompting central banks to rely on communication as a key policy tool increasingly (Blinder et al. 2008). Former Chair of the Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke once remarked that “Monetary policy is 98 percent talk and only 2 percent action.”1 For instance, central banks issue statements about the future path of their policy tools to influence public expectations and economic behavior directly when interest rates approach the effective lower bound, known as forward guidance (Bassetto 2019). In China, the role of expectation management has steadily gained prominence since the phrase “stabilizing expectations” first appeared in the Government Work Report in 2009. In 2015, China's central bank, the People's Bank of China (PBC), introduced a dedicated section on “Central Bank Communication and Expectation Management” in its quarterly Monetary Policy Implementation Report (MPIR). The significance of expectation management was further underscored in July 2018 when the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee put forward the goal of stabilizing expectations. This emphasis was reaffirmed in the 2021 release of the 14th 5-Year Plan, which stressed the necessity of focusing on expectation management and guidance. Since then, the annual Central Economic Work Conference has consistently highlighted the critical role of social expectations in driving economic development2.

Exploring the impact of central bank communication and expectation management in China is crucial. For one thing, as the world's second-largest economy with increasing capital openness, China is expected to exert growing global spillover effects in policy. For another, PBC communication exhibits certain characteristics that distinguish it from those of developed countries, implying that findings from those economies may not be directly applicable to China. As noted by the previous PBC Governor Zhou Xiaochuan, the PBC's policy has multiple objectives. These include four annual goals: maintaining price stability, promoting economic growth, fostering employment, and ensuring a balanced balance of payments. There are two dynamic objectives: financial reform and opening-up, as well as the development of financial markets3. In practice, the PBC sometimes communicates to achieve various conflicting objectives simultaneously. This may make it difficult for the public to understand the purpose of central bank communication, thus undermining its effectiveness. Furthermore, PBC communication remains in its early stages. In terms of forward guidance, it primarily provides ambiguous descriptions of future economic conditions and monetary policy deployment (Guo and Zhou 2018).

In China, emphasizing central bank communication and expectation management has practical significance today. On the one hand, expectations affect macroeconomic fluctuations by influencing the behavior of market participants such as individuals and enterprises. According to the self-fulfilling prophecy theory (Merton 1948), a widespread belief in an economic downturn can result in reductions in consumption and investment, ultimately leading to an actual economic recession. On the other hand, given the complexity of China's current monetary policy environment, communication is essential for the PBC to enrich its monetary policy toolkit and improve policy effectiveness. First, the ability of conventional monetary policy to stabilize macroeconomic fluctuations has weakened with China's economic growth slowing down (Guo et al. 2016), and the normal monetary policy space is also gradually shrinking. For example, data from Wind show that the deposit reserve ratio of small and medium-sized deposit financial institutions in China has fallen from 18% in 2014 to 7% at the beginning of 2024, and the space for interest rate cuts has been greatly narrowed. Therefore, as Yi Gang, former governor of the PBC, noted in 2019, it is necessary to cherish the normal monetary policy space to support the sustainable development of the economy4. Second, the transmission of conventional monetary policy to the real economy in China is not smooth (Wu and Lian 2016), and monetary policy actions affect economic conditions only after a long and variable lag (Friedman 1961). Besides, prolonged loose monetary policy can lead to an accumulation of excess liquidity, which may cause inflation. Third, as the PBC continues to innovate its monetary policy tools, certain monetary policy operations in practice sometimes serve purposes that diverge from their theoretically noticeable effects (Wang et al. 2019)5. As such, it is essential for the central bank to communicate the purpose and function of these tools to the market to mitigate the public's understanding bias and secure the cooperation of market participants effectively. In summary, regular information releases alongside sporadic policy communication can help the PBC preserve normal monetary policy space and enhance policy effectiveness by directly guiding market participants' expectations and economic behavior.

Existing research on PBC communication and expectation management primarily falls into two categories. One focuses on simulating the effects of expectation management by constructing theoretical models such as DSGE (Guo et al. 2016; Guo and Zhou 2018). Another uses text analysis or event study methods to examine the impact of PBC communication on macroeconomic variables like asset prices, the RMB exchange rate, or inflation expectations (Xiong and Wang 2012; Zhu et al. 2016; McMahon et al. 2018). There are relatively few empirical studies on the micro-level effects of PBC communication, which mainly focus on enterprises (including banks). For example, Wang and Wang (2015) explore the relationship between central bank expectation management and bank risk-taking, while Wang et al. (2019) examine the impact of central bank verbal communication and actual actions on corporate investment behavior. The role of PBC communication in guiding individual expectations has received limited attention in the literature, largely due to the lack of individual expectation data before and after the central bank communication6. However, research on this topic holds significant practical importance. On the one hand, as the scope for conventional monetary policy narrows, China is increasingly moving toward structural adjustments in monetary policy. Understanding the heterogeneous effects of PBC communication on individuals can aid in more targeted communication efforts, referred to as structural communication, thereby improving communication efficiency. On the other hand, public expectations affect their consumption behavior, and consumption is playing a growing role in economic growth. According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China, in 2023, final consumption expenditure, gross capital formation, and net exports of goods and services contributed 82.5%, 28.9%, and –11.4% to economic growth, respectively, making consumption the dominant driver of GDP growth. Therefore, comprehending how PBC communication influences individuals' expectations and consumption behavior driven by expectations is crucial for effectively expanding domestic demand and thus fostering economic growth in China.

In addition to the difficulty in obtaining data, identifying the causal impact of China's central bank communication on individuals' expectations presents another key challenge. Specifically, central bank communication usually occurs alongside other macroeconomic events or policies, making it challenging to disentangle their influence on individuals' expectations. Recent years have witnessed a credible revolution in causal inference, emphasizing a return to the experimentalist tradition (Li and Xu 2022). Chen et al. (2023) argue that randomized controlled trials are more advantageous for policy evaluation because of their randomness, in contrast to quasi-experiments. By comparing the performance of different experimental groups, we can get attributional feedback for policy implementation, such as identifying the mechanism of the policy's functioning and uncovering reasons for failure. In developed economies, researchers have tried to address issues like data unavailability and endogeneity in this area of study by using survey experiments. Some utilize survey data collected before and after actual central bank communication (Enders et al. 2019; Lamla and Vinogradov 2019), while others use experimental surveys embedded with communication messages to evaluate the effectiveness of central bank communication (Bholat et al. 2019; Beutel et al. 2021). These studies reach mixed conclusions on the efficacy of central bank communication.

To examine the impact of PBC communication on individuals' macroeconomic expectations, we conduct a randomized experiment referring to Beutel et al. (2021). We use the summary of China's MPIR released by the PBC for the third quarter of 2022 as the information intervention material for the treatment groups. The exogenous changes induced by the information intervention help assess the effectiveness of central bank communication at the individual level. Previous research on the impact of PBC communication on individuals' expectations often struggles to separate the effects of concurrent macroeconomic events or policies. This study overcomes the endogeneity issue by using an experimental design that ensures any systematic differences between randomly assigned treatment and control groups arise primarily from the information intervention. The experiment was conducted offline and online in December 2022, with participants mainly consisting of economic and financial practitioners and full-time students majoring in finance and economics7. The key findings of this study are: (1) Positive central bank communication reduces individuals' expectations of the likelihood of a recession. (2) Clear and specific retrospective communication is more effective than vague and complex forward-looking communication. (3) The impact of central bank communication on individuals' expectations may vary across different groups, with those who read financial news less frequently being more susceptible to its influence. (4) After guiding individuals' macroeconomic expectations, central bank communication further affects individuals' consumption plans, contributing to the central bank's economic growth objectives.

The rest of the article is structured as follows: Section 2 surveys the related literature. Section 3 describes the experimental design and data. Section 4 empirically analyzes the causal effect between central bank communication and individuals' macroeconomic expectations. The impact of central bank communication on public consumption plans is presented in Section 5. Section 6 concludes.

2 Literature Review

We contribute to the growing literature on the effectiveness of central bank communication, especially China's central bank communication. By event study and text analysis methods, existing literature has extensively investigated the impact of central bank communication in developed economies on financial markets, including monetary policy announcements, regularly published reports, and governor speeches (Hansen and McMahon 2016; Nakamura and Steinsson 2018; Cieslak and Schrimpf 2019; Ehrmann and Talmi 2020; Gardner et al. 2022). For example, Hansen and McMahon (2016) use computational linguistics tools to construct indicators for Federal Reserve communication. The empirical results based on the Factor-Augmented Vector Autoregressive (FAVAR) model show that communications regarding the current economic situation and forward guidance affect both the interest rate market and the stock market, but forward guidance is more effective. Cieslak and Schrimpf (2019) categorize the communications of the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, the Bank of England, and the Bank of Japan into monetary news and nonmonetary news, finding that nonmonetary news has a greater impact on the financial market during the financial crisis while monetary news has become more and more important since 2013. For China, abundant studies use text analysis methods to construct communication indices and investigate the effect of PBC communication on the capital market. They have explored the different impacts of various communication channels and monetary policy orientations. Zhu et al. (2016) employ the Exponential Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (EGARCH) model to assess the impact of PBC communication on RMB exchange rate fluctuations and confirm the positive role of communication in exchange rate expectation management. They also find that written communication is more effective than oral communication, and among oral communications, those delivered by the governor are more effective than others. Using an event study approach, Zou et al. (2020) find that loose PBC communication positively influences China's stock market, while the impact of contractionary communication is negative. McMahon et al. (2018) provide empirical evidence that the release of quarterly MPIR reduces the price volatility of short-term notes.

However, there is limited research examining the impact of China's central bank communication on individuals' expectations, in contrast to its influence on financial markets. Most studies lack accurate data on individual expectations, relying instead on asset prices and economic models to estimate inflation expectations. For instance, Yan and Gao (2017) construct proxy variables for inflation expectations of the public and financial market participants based on survey indices and treasury bond yield data. They argue that information from PBC significantly influences inflation expectations, with an effect better than monetary policy actions. Wang and Wang (2015) estimate inflation expectations using central bank expectation management information and other economic indicators, discovering that PBC's expectation management policy helps reduce inflation expectations volatility. Nevertheless, Guo et al. (2023) highlight that asset prices only indirectly reflect expectations, subject to complex influencing factors and considerable noise. Hong et al. (2023) also point out that constructing an econometric model to extract effective information from the financial market to predict inflation is inferior to forecasting inflation expectations based on survey data.

In developed economies, a broad body of empirical literature assessing the influence of central bank communication on the beliefs and expectations of the general public or firms through survey experiments in recent years. Lamla and Vinogradov (2019) surveyed consumers' expectations about inflation and interest rates before and after the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings. The empirical results indicate that although Federal Reserve communications have no measurable direct effect on personal economic expectations, they make the public more likely to receive the news released by the central bank. Enders et al. (2019) compare the changes in German enterprises' expectations before and after the monetary policy announcement. They find that a moderately contractionary monetary policy announcement lowers output and price expectations, while a moderately expansionary surprise raises them. D'Acunto et al. (2020) conducted a large-scale random questionnaire experiment, verifying that communication about targets is better than communication about policy instruments in managing expectations. Based on a random information experiment, Beutel et al. (2021)8 find that individuals expect the possibility of a financial crisis to increase after receiving financial risk warning information from the central bank.

The above studies use survey experiments to obtain real, rather than estimated, individual expectations across various categories, such as inflation, output, and financial conditions. Leveraging these real expectation data allows us to analyze the heterogeneous responses of different groups to central bank communication, thereby facilitating more tailored and structured policy implementation. Furthermore, survey experiments offer another distinct advantage: they allow for a clearer identification of the causal impact of central bank communication. In practice, central bank communication often responds to events in the real economy, which can lead to reverse causality issues in identification. Moreover, some macroeconomic events that coincide with communications may cause omitted variable bias. As such, isolating the effect of central bank communication itself is challenging. By a randomized controlled design with control and treatment groups, survey experiments minimize systematic differences between them other than the experimental intervention, effectively alleviating the endogeneity issue. Of course, every coin has two sides. While the advantages of survey experiments are clear, they also come with limitations: on one hand, unlike research based on existing data published by the authorities, investigating the effectiveness of central bank communication through survey experiments requires more sophisticated pre-designs and can be costly; on the other, due to the controlled nature of experiments, such studies often struggle to stimulate the complexity of the real world and typically focus only on a few specific aspects of central bank communication. Our study focuses on the impact of central bank communication content by designing treatment and control groups based on content variations rather than the mode or transmission of communication. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to provide direct evidence on the effects of PBC communication on individuals' expectations about macroeconomy by survey experiment.

In addition, we contribute to relatively few studies on the impact of PBC communication on personal consumption. The relevant literature primarily simulates the effectiveness of PBC communication in influencing household consumption through the dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) model or laboratory experiment (Guo et al. 2016; He and Zhao 2022). Guo et al. (2016) construct a DSGE model incorporating expectation error shocks and expectation management policy. The numerical simulations indicate that PBC's provision of information with high accuracy can reduce the deviation of public expectations, thereby reducing the fluctuation of household consumption and promoting its faster return to a steady state. He and Zhao (2022) carry out a laboratory experiment based on the intertemporal consumption-savings model, and find that forward guidance with a high commitment level, which provides guarantees, can guide individuals' expectations and smooth consumption.

In summary, this article contributes to existing literature in two ways. First, it fills a gap in the research on the effectiveness of PBC communication on individuals' expectations. By using a survey experiment to obtain individuals' expectations about the macroeconomy in China, we not only alleviate the potential endogenous problem in this area of research but also conduct a heterogeneity analysis. Second, this article provides the first empirical evidence of the causal effect of PBC communication on personal consumption planning, which lays a foundation for a deeper understanding of how PBC communication influences consumer behavior and the improvement of PBC communication.

3 Randomized Experiment

3.1 Experiment Design

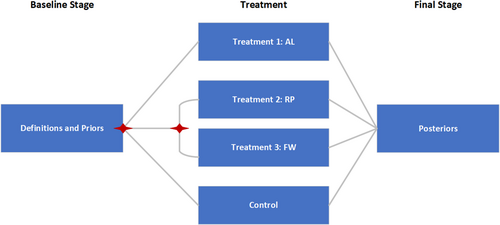

We executed a randomized information experiment embedded in a survey online and offline from December 3 to December 12, 2022, during which time 656 valid questionnaires were gathered9. This experimental setup consists of three stages: a baseline stage, collecting respondents' prior macroeconomic expectations and consumption plans; a treatment stage, during which respondents are randomly assigned to either receive the summary of China's MPIR for the third quarter of 202210 or receive no materials; a final stage, eliciting posterior expectations and consumption plans (see Figure 1).

3.1.1 Baseline Stage

In this stage, respondents are asked to answer questions about demographic characteristics such as gender, age group, and risk appetite. Then, similar to Roth and Wohlfart (2020) and Beutel et al. (2021), respondents receive a brief introduction on how to express expectations for future events in terms of probability values11. Next, respondents are tasked with giving their expectations for personal disposable income in the next 12 months. Subsequently, we provide them with the concept of a recession and elicit their expectations for the probability of a recession in China in the next 12 months. In addition, respondents are asked about their total consumption expenditure plans in the next 12 months. The main questions in the questionnaire are shown in Supporting Information S1: Appendix A. The two questions most relevant to this study are presented below:

Macroeconomic expectation: What do you think is the probability of a “recession” occurring within the next 12 months in China?12

Consumption plan: What do you anticipate your consumption expenditure will be over the next 12 months?

3.1.2 Treatment Stage

During the treatment stage, individuals are randomly assigned to one of four subgroups. Respondents in the control group do not receive any additional reading materials. In contrast, respondents in treatment group 1 receive the full summary of the MPIR for the third quarter of 2022 (see Supporting Information S1: Appendix B), a highly condensed version of the full MPIR text. The first half focuses on the economic conditions and monetary policy since the beginning of the year, while the second half offers a perspective on the economic conditions and monetary policy in the future13. Respondents in treatment group 2 receive only the first half of the summary, which begins with macroeconomic data, such as GDP, highlighting the apparent rebound of China's economy in the first three quarters of 2022. In addition, this section reviews the major monetary policies implemented over the past three quarters, indicating a moderately loose stance through increased credit volumes and declining interest rates. Subjects in treatment group 3 receive the second half of the summary, which mainly contains the content that the long-term positive fundamentals of the economy will remain and that the support of sound monetary policy for the real economy will be enhanced in the future. However, this portion is expressed more generally and lacks specific commitments. Overall, the summary of the MPIR for the third quarter of 2022 conveys a positive outlook regarding macroeconomic conditions and monetary policy.

3.1.3 Final Stage

In the final stage, respondents are prompted to answer the same questions as in the baseline stage so that we can measure changes in their expectations regarding macroeconomic conditions, income levels, and consumption. Next, respondents need to complete a quiz designed to measure their economic and financial literacy. Finally, we gather information about their highest level of education, type of occupations, study experience in finance and economics, frequency of reading financial news, and investment conditions. Through this experiment embedded in the questionnaire, we can evaluate the effectiveness of PBC communication. See Supporting Information S1: Appendix C presents the principles of this experiment.

3.2 Data

3.2.1 Variable Definition and Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the main variables used in this study. When the subject is randomly assigned to treatment group 1, that is, he or she is expected to read the complete summary of the MPIR, is equal to one, and zero otherwise. Similarly, for respondents in treatment group 2 or treatment group 3, or is equal to one, and zero otherwise. denotes the expectation of the probability of a recession in China for the next year as reported by the respondent in the baseline stage, while reflects the expectation of a recession in the final stage, with a value from 0 to 10014. Variables about demographic characteristics (gender, age group, self-reported risk appetite, full-time student status, and academic degree) and economic knowledge level (financial literacy, study experience in finance and economics, frequency of reading financial news, and security investment conditions) are all binary variables. Specifically, the variable equals 1 if the respondent is female. The variable is coded as 1 for respondents aged 18–25 and 0 for those aged 26–30, 31–40, or 41–50. The variable equals one when the respondent's reported risk appetite is greater than or equal to the average level of all the respondents, zero otherwise. If the individual is a full-time student, the dummy variable is equal to 1. When the respondent is an undergraduate or holds a bachelor's degree, the variable equals 1. It equals 0 for master's students or those with a master's degree, as well as for PhD students or those with a doctoral degree. The variable is equal to 1 if the respondent answers all three financial literacy test questions15 in the questionnaire correctly. When the respondent has graduated or is studying a finance or economics major, the variable is equal to 1. The variable is coded as 0 for respondents who read financial news “hardly ever or never,” “once a month,” or “once a week,” and as 1 for those who read it “every day.” If the individual invests in individual stocks, funds, options, or futures, the dummy variable is equal to 1. and denote the expected total personal disposable income and consumption expenditure for the upcoming 12 months, respectively.

| Mean | SD | Min | Median | Max | Observations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 656 | |

| 0.16 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 656 | |

| 0.18 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 656 | |

| 46.06 | 28.58 | 0.00 | 46.50 | 100.00 | 656 | |

| 41.96 | 27.65 | 0.00 | 40.00 | 100.00 | 656 | |

| 0.62 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 656 | |

| 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 656 | |

| 0.56 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 656 | |

| 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 656 | |

| 0.27 | 0.44 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 656 | |

| 0.66 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 656 | |

| 0.78 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 656 | |

| 0.37 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 656 | |

| 0.70 | 0.46 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 656 | |

| 166595.47 | 166726.85 | 15000.00 | 100000.00 | 600000.00 | 649 | |

| 164741.88 | 165759.77 | 18000.00 | 100000.00 | 600000.00 | 649 | |

| 85990.91 | 82315.63 | 10000.00 | 50000.00 | 300000.00 | 649 | |

| 87523.57 | 83114.94 | 10000.00 | 50000.00 | 300000.00 | 649 |

- Note: Variables and are measured in %; Personal disposable income and consumption expenditure are both measured in RMB.

In all samples, 35% of the subjects are allocated to treatment group 1 to read the complete summary of the MPIR; 16% and 18% of the respondents are assigned to treatment groups 2 and 3, respectively, to read the first half and the second half of the MPIR, respectively. Additionally, 32% of individuals are assigned to the control group without reading any additional information. The proportion of participants in each group is consistent with our random distribution assignment. The respondents are mainly between 18 and 40 years old16. Nearly half of the respondents are full-time students, and 66% of them have obtained or are pursuing a master's degree. Generally, the respondents possess a high level of economic and financial knowledge: 66% of them answer all three financial literacy test questions correctly, 78% have experience in financial-related professional learning, 65% read financial news at least once a week, and 70% hold some investment in stocks, funds, options, or futures. To address outliers in the personal disposal income and consumption expenditure variables, we winsorize these relevant variables at the top and bottom five percent, following Roth and Wohlfart (2020).

3.2.2 A One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) of Equality Test

According to the experimental design, respondents are randomly assigned to the treatment and control groups to ensure that there are no systematic differences between the four subgroups, except for the different materials allocated to individuals during the treatment stage. We use a one-way ANOVA test to examine the equality among these subgroups for all pretreatment expectations and sample characteristics. Columns 2–5 of Table 2 present the mean values of the four groups for these variables, and column 6 reports the p-values of the test statistics. The null hypothesis that the mean values of these subgroups are equal cannot be rejected for all pretreatment and sample characteristic variables, which validates the randomness of our experimental design. Nevertheless, in the regression below, these variables are still used as control variables to mitigate potential endogeneity issues.

| Control | Treatment 1 | Treatment 2 | Treatment 3 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48.34 | 44.70 | 43.68 | 46.71 | 0.455 | |

| 152237.50 | 171863.11 | 183155.50 | 167578.95 | 0.428 | |

| 78918.27 | 88534.22 | 95661.76 | 85222.81 | 0.367 | |

| 0.68 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.59 | 0.159 | |

| 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.54 | 0.791 | |

| 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.943 | |

| 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.52 | 0.43 | 0.536 | |

| 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.716 | |

| 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.718 | |

| 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.609 | |

| 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.332 | |

| 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.418 | |

| Observations | 210 | 227 | 103 | 116 |

- Note: The last column reports the p values from a one-way ANOVA test assessing whether each row variable differs significantly across the four groups: Control, , , .

4 Central Bank Communication and the Expectation About Macroeconomy

According to the macroeconomic models with incomplete information, the general public does not fully understand the current economic situation and monetary policy due to infrequent updates to their information sets or the presence of noisy information (Roth and Wohlfart 2020). Central banks usually invest more resources in estimating and predicting economic conditions and are considered to possess superior information about the economic environment (Blinder et al. 2008). Therefore, in theory, when the public believes that the central bank is credible, the central bank can provide information about economic conditions and monetary policy to effectively manage public expectations by prompting individuals to update their personal information sets and gain a better understanding of the economic situation and monetary policy (Morris and Shin 2002; Wang et al. 2019). In this section, we validate this theoretical conclusion using experimental data.

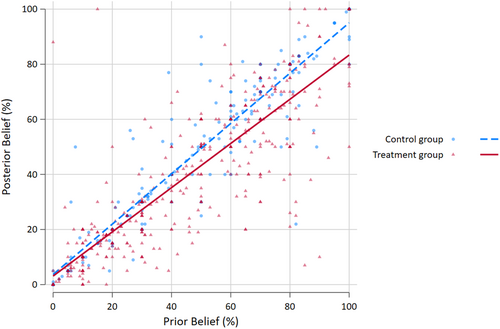

4.1 Simple Analysis

After combining the three treatment subgroups into a single treatment group, we present scatterplots with fitted lines in Figure 2 to compare the correlations between recession probability expectations at the baseline and final stages for the treatment and control groups. The slope of the fitted line for the treatment group is lower than that of the control group, which tentatively suggests that positive central bank communication can reduce individuals' expectations of the probability of a recession.

Furthermore, we conduct a simple differential calculation of the mean macroeconomic expectations for each treatment group compared with the control group. Table 3 shows the differences in the means of macroeconomic expectations within and between subgroups, as well as the difference-in-difference (DID) values that we focus on in the empirical analysis below. It is noteworthy that even respondents in the control group adjust their views on the future by lowering their expectations of the probability of a future recession. Zwane et al. (2011) argue that simply participating in a survey may prompt respondents to think more and change their expectations. However, this confounding effect is counteracted when considering the DID values for the three treatment groups. Compared with the control group, respondents in all three treatment subgroups significantly reduce their expectations of recession probability, with the most significant reduction observed among participants assigned to read only the first half of the MPIR summary and the smallest decrease found among those designated to read the second half of the MPIR summary.

| Levels | Differences between groups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| 48.340 | 44.705 | 43.680 | 46.707 | –3.636 | –4.661 | –1.634 | |

| 47.836 | 38.480 | 37.058 | 42.474 | –9.356*** | –10.777*** | –5.362* | |

| –0.505 | –6.225 | –6.621 | –4.233 | –5.720*** | –6.117*** | –3.728*** | |

- Note: represents the control group, and . Asterisks *** and * represent significance at the 1% and 10% levels, respectively.

The above results roughly suggest a negative causal relationship between positive central bank communication and individual expectations of recession probability. We explore it in more detail below.

4.2 Regression Analysis

4.2.1 Effectiveness of Central Bank Communication

Table 4 reports the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation results of Equation (1), showing that the coefficients , , and are all negative and statistically significant at the 1% level18. This suggests that information intervention can effectively change individuals' expectations about the macroeconomy. That is, positive PBC communication reduces individuals' expectations of an economic recession. The results in columns 1 and 2 of Table 4 show that among the information intervention materials, the first half of the MPIR summary has the best effect, followed by the whole summary, and the second half demonstrates the least impact. This preliminarily indicates that clear and specific retrospective communication is more effective than vague communication, a notion we further investigate in the next section.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| –6.309*** | –6.586*** | |||

| (1.295) | (1.297) | |||

| –6.872*** | –7.033*** | |||

| (1.483) | (1.496) | |||

| –3.993*** | –4.150*** | |||

| (1.333) | (1.331) | |||

| –5.833*** | –6.056*** | |||

| (1.011) | (1.009) | |||

| –0.162*** | –0.155*** | –0.161*** | -0.154*** | |

| (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.020) | |

| 7.325*** | 9.157*** | 7.276*** | 8.986*** | |

| (1.167) | (2.539) | (1.165) | (2.529) | |

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| 0.139 | 0.151 | 0.134 | 0.147 | |

| 656 | 656 | 656 | 656 |

- Note: contains individual-specific controls (gender, age group, self-reported risk appetite, full-time student status, and academic degree). includes controls indicating levels of economic knowledge (financial literacy, study experience in finance and economics, frequency of reading financial news, and security investment conditions). Asterisk *** denotes significance at the 1% level. The standard errors robust to heteroskedasticity are in parentheses.

In addition, we aggregate the three treatment subgroups to compare the expectation changes with the control group, as presented in columns 3 and 4 of Table 4. As long as the subjects are expected to read the MPIR summary in the treatment stage, the variable is equal to 1; otherwise, it is 0. The results in column 4 reveal that after the information intervention, individuals' expectations of economic recession decrease by an average of 6.06%19, which amounts to 13.16% of the mean prior belief of 46.06%. With rational inattention, the public has an incomplete understanding of the macroeconomic situation and monetary policy. By providing relevant positive information, PBC communication makes the public more optimistic about the future and narrows the information bias among them.

4.2.2 Comparison of the Effectiveness of Different Types of Communication

Same as Equation (1), is the change of individual 's expectation regarding a recession before and after the treatment stage. is a binary variable that is equal to one if individual is supposed to read the first half of the MPIR summary and equals zero if is expected to read the second half of the summary. The other settings in Equation (2) are the same as those in Equation (1).

Columns 1 and 2 of Table 5 present the OLS estimates for Equation (2). The coefficient is negative and statistically significant at the 10% level, indicating that the first half of the summary (retrospective communication) has a greater negative effect on the recession expectation than the second half (forward-looking communication). The results show that retrospective communication by the PBC is more influential than forward-looking communication in guiding individuals' expectations regarding the macroeconomy. On the one hand, retrospective communication enhances public understanding of PBC's goals and actions (Kryvtsov and Petersen 2021) and alleviates individuals' pessimistic expectations about the economy by providing positive information on past economic conditions and monetary policy. On the other hand, although the forward-looking communication conveys an optimistic outlook for the future macroeconomy and PBC's monetary policy, it also describes the current challenging external environment and an unstable foundation for economic recovery, which may offset the effect of the positive outlook (Wang et al. 2019). In addition, forward-looking communication is ambiguous, while retrospective communication uses clearer and more specific economic and financial data that is easier to understand and more credible. The conclusion that clear and simple communication is preferable to complex and ambiguous communication aligns with existing literature (Guo and Zhou 2018; Bholat et al. 2019; Beutel et al. 2021). The experimental results of Kryvtsov and Petersen (2021) also support the idea that simple and relevant retrospective announcements from the central bank are more effective in reducing the volatility of individuals' expectations than forward-looking statements without specifying the timing of future policy changes. Additionally, the information on economic policy changes obtained by economic agents includes the policy change information itself and policy noise. Economic agents act in full accordance with this information when the noise is zero, while they do not react in any way when the noise is infinitely large and economic policy uncertainty is extremely high (Hong et al. 2023).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| –2.895* | –3.032* | |||

| (1.700) | (1.761) | |||

| 0.619 | 0.598 | |||

| (1.651) | (1.694) | |||

| –0.167*** | –0.166*** | –0.217*** | –0.210*** | |

| (0.033) | (0.034) | (0.033) | (0.033) | |

| 3.577** | 4.170 | 2.861* | 1.880 | |

| (1.528) | (3.641) | (1.622) | (4.345) | |

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| 0.136 | 0.161 | 0.147 | 0.164 | |

| 219 | 219 | 330 | 330 |

- Note: contains individual-specific controls (gender, age group, self-reported risk appetite, full-time student status, and academic degree). includes controls indicating levels of economic knowledge (financial literacy, study experience in finance and economics, frequency of reading financial news, and security investment conditions). Asterisks ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. The standard errors robust to heteroskedasticity are in parentheses.

Moreover, we replace with in Equation (2) to compare the influence of the full summary with that of only the first half. If the individual is allocated to read the full summary of the MPIR in the treatment stage, the variable is equal to one. If is expected to read only the first half of the summary, is equal to zero. The results in columns 3–4 indicate that there is no significant difference between these two types of communication. This finding can be attributed to information overload. Generally speaking, an individual's performance (i.e., the quality of decision-making or reasoning) correlates positively with the amount of information they receive. However, when the information received exceeds a certain threshold, additional content will no longer be integrated into the decision-making process, a phenomenon known as information overload (Chewning and Harrell 1990; Eppler and Mengis 2004). The threshold for information overload is influenced not only by information quantity but also by characteristics of the information itself, such as ambiguity, relevance, uncertainty, or complexity (Keller and Staelin 1987; Schneider 1987). In this study, after reading the first half of the summary, the complex and ambiguous messaging in the second half causes the subjects to experience information overload and has no additional impact on their expectations of a recession. Consequently, compared with respondents who only read clear and specific retrospective communication content, respondents who read the full MPIR do not reduce their recession expectations more largely.

4.2.3 Heterogeneity Analysis of Communication Effectiveness

Are there significant quantitative differences in the effectiveness of central bank communication among respondents with different characteristics? To answer this question, we examine the average treatment effects (ATEs) across samples categorized by gender, degree, financial literacy, major, and frequency of reading financial news. The regression results are presented in Table 6. Specifically, undergraduates or respondents with a bachelor's degree are in the “Yes” group, while the others are in the “Low” group. Participants who correctly answer all three financial literacy test questions are assigned to the “High” group, while those who fail to do so are placed in the “Low” group. Individuals who have graduated or are studying finance, economics, or related fields are classified into the “Yes” group; otherwise, they belong to the “No” group. In addition, daily readers of financial news are included in the “Yes” group, while those reading less frequently are placed in the “No” group. We aggregate the three treatment subgroups and compare them to the control group, with each regression controlling for respondents' prior expectations and the demographic and economic knowledge variables noted above.

| Gender | Bachelor | Financial Literacy | Finance/Economics Major | Reading FE News Every Day | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Yes | No | High | Low | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

| –7.377*** | –3.864* | –4.189** | –6.810*** | –5.082*** | –7.796*** | –6.140*** | –5.706** | −3.565** | −7.559*** | |

| (1.190) | (1.969) | (1.941) | (1.174) | (1.125) | (2.038) | (1.091) | (2.597) | (1.622) | (1.303) | |

| –0.147*** | –0.161*** | –0.126*** | –0.164*** | –0.146*** | –0.164*** | –0.137*** | –0.177*** | –0.129*** | –0.165*** | |

| (0.023) | (0.036) | (0.044) | (0.022) | (0.023) | (0.036) | (0.021) | (0.046) | (0.033) | (0.025) | |

| 6.572** | 9.712** | 5.068 | 9.580*** | 4.095 | 15.574*** | 11.243*** | 6.542 | 10.160*** | 10.496*** | |

| (2.632) | (4.461) | (3.325) | (3.117) | (3.115) | (4.621) | (3.150) | (4.143) | (3.828) | (3.299) | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 0.178 | 0.131 | 0.124 | 0.169 | 0.139 | 0.195 | 0.147 | 0.207 | 0.134 | 0.159 | |

| 406 | 250 | 174 | 482 | 430 | 226 | 514 | 142 | 240 | 416 | |

| SUEST p-value | 0.119 | 0.236 | 0.234 | 0.873 | 0.051 | |||||

- Note: contain demographic characteristics (gender, age group, self-reported risk appetite, full-time student status, and academic degree) and economic knowledge level control variables (financial literacy, study experience in finance and economics, frequency of reading financial news, and security investment conditions). Asterisks ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. The standard errors robust to heteroskedasticity are in parentheses.

The regression results indicate that the absolute value of the average treatment effect of PBC communication on female respondents is greater than that on male counterparts, although the difference is not statistically significant. This finding is consistent with the conclusions drawn by Armantier et al. (2016) and Beutel et al. (2021). One possible reason is that women have less confidence in their prior beliefs than men, which leads to a pronounced impact of information intervention on their expectations. In addition, respondents who do not read financial news daily show a significantly larger decline in the recession expectations to daily readers. This may be attributed to the fact that less frequent readers obtained more positive new information from the summary of the MPIR for the third quarter of 2022, whereas daily readers may have already been aware of the information before participating in the experiment. However, the average treatment effects of PBC communication do not exhibit significant differences across participants with varying education levels (bachelor's degree or higher), financial literacy20, or backgrounds in finance or economics. The following are some possible reasons for the above results: First, the key positive information about economic conditions in the PBC communication materials we provided is relatively easy to capture and understand21, requiring neither advanced education nor specialized financial knowledge. Second, regardless of education, financial literacy, or economic background, respondents generally have almost similar levels of trust in the PBC's MPIR summary. We examine the impact of these three variables on the treatment group's trust22 in the information from the PBC's MPIR summary. The results show that these variables have no significant effect on trust (see Supporting Information S1: Appendix E), which supports the second explanation. Third, prediction patterns may remain consistent across various groups, such as students, families, and financial market participants (Cornand and Hubert 2020; Kryvtsov and Petersen 2021), meaning that information interventions influence the expectations of these groups similarly, with no significant differences on average.

4.2.4 Robustness Checks

To exclude the influence of extreme values on our results, we winsorize or trim and at the top and bottom 2% or 5%. We obtain qualitatively similar results as above, showing that respondents reduce their expectations of recession probability after reading the summary of the MPIR for the third quarter of 2022 (see Table 7). Additionally, the treatment group participants may not have read the intervention materials we provided, that is, there are non-compliers. To test whether this issue could bias the estimation results of Equation (1), we restrict the treatment group to those who answer the question regarding the trust level in the information from the MPIR summary they have just read (see Question A.13 in Appendix E of Supporting Information S1)23. The regression results are presented in Table 8, where the results in column (2) are nearly identical to those in column (4) of Table 4. Thus, the conclusion that PBC communication can effectively guide individuals' macroeconomic expectations is robust.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winsorize 2% | Winsorize 5% | Trim 2% | Trim 5% | |

| –5.690*** | –5.130*** | –4.663*** | –4.335*** | |

| (0.860) | (0.738) | (0.765) | (0.703) | |

| –0.130*** | –0.116*** | –0.096*** | –0.081*** | |

| (0.015) | (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.014) | |

| 7.212*** | 5.665*** | 4.434*** | 3.158* | |

| (1.937) | (1.630) | (1.711) | (1.646) | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 0.157 | 0.163 | 0.129 | 0.121 | |

| 656 | 656 | 631 | 544 |

- Note: contain demographic characteristics (gender, age group, self-reported risk appetite, full-time student status, and academic degree) and economic knowledge level control variables (financial literacy, study experience in finance and economics, frequency of reading financial news, and security investment conditions). Asterisks *** and * denote significance at the 1% and 10% levels, respectively. The standard errors robust to heteroskedasticity are in parentheses.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| –5.952*** | –6.327*** | |

| (1.055) | (1.056) | |

| –0.162*** | –0.153*** | |

| (0.021) | (0.021) | |

| 7.303*** | 9.232*** | |

| (1.211) | (2.693) | |

| No | Yes | |

| 0.136 | 0.152 | |

| 598 | 598 |

- Note: contain demographic characteristics (gender, age group, self-reported risk appetite, full-time student status, and academic degree) and economic knowledge level control variables (financial literacy, study experience in finance and economics, frequency of reading financial news, and security investment conditions). Asterisk *** denotes significance at the 1% level. The standard errors robust to heteroskedasticity are in parentheses.

5 Further Analysis

Columns 1 and 2 of Table 9 show that an individual's planned spending for the upcoming year significantly increases by 3% on average after the information intervention. There are two possible reasons behind this: First, economic recessions accelerate labor market deterioration (Farber 2011), while positive central bank communication makes individuals more optimistic about the future economic situation and labor market, thereby raising their expectations of permanent income levels (Krueger et al. 2016; Yagan 2019). Consumption theories suggest that individual consumption increases with permanent income (Friedman 1957; Houthakker 1958). Second, positive central bank communication can reduce individuals' expectations of future income uncertainty, thereby lowering precautionary savings (Lusardi 1998; Parker and Preston 2005). This, in turn, can enhance individuals' future consumption plans. In addition, we examine the impact of central bank communication on the change rate of personal expected disposable income over the next 12 months by estimating Equation (3) where . The results are represented in columns 3 and 4 of Table 8, and the impact of central bank communication on the income change rate in the next 12 months is not statistically significant. It is important to note that this result does not contradict our first hypothesis, namely the permanent income hypothesis, as short-term income differs from permanent income24. On the contrary, this finding is consistent with the view that income exhibits stickiness in the short run.

| Consumption change rate | Income change rate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| 0.030* | 0.034** | 0.010 | 0.011 | |

| (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.012) | (0.012) | |

| 0.043*** | 0.039 | 0.015 | 0.045 | |

| (0.015) | (0.036) | (0.011) | (0.031) | |

| Yes | Yes | |||

| Yes | Yes | |||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| 0.020 | 0.034 | 0.032 | 0.039 | |

| 649 | 649 | 649 | 649 | |

- Note: contains individual-specific controls (gender, age group, self-reported risk appetite, full-time student status and academic degree). includes controls indicating levels of economic knowledge (financial literacy, study experience in finance and economics, frequency of reading financial news, and security investment conditions). Asterisks ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. The standard errors robust to heteroskedasticity are in parentheses.

6 Conclusion

Central bank communication is increasingly becoming a critical tool for managing public expectations and enhancing the effectiveness of monetary policy. Although research on the effectiveness of the PBC's communication has gained growing attention, few studies directly examine the impact of the PBC's communication on individuals' macroeconomic expectations. This study incorporates the summary of China's MPIR for the third quarter of 2022 as an information intervention in a survey for individuals. Using this random information experiment, we assess the effectiveness of the PBC's communication in influencing individuals' expectations of the probability of an economic recession. The findings of this article are as follows: (1) By providing positive information about past or future economic conditions and monetary policies, central bank communication can reduce individuals' expectations of an economic recession. (2) Clear and specific retrospective communication is more effective than vague and complex forward-looking communication. (3) The impact of central bank communication on individuals' expectations of an economic recession is heterogeneous. Individuals who read financial news less frequently are more likely to be influenced. (4) After affecting individuals' macroeconomic expectations, central bank communication further affects personal consumption plans, and the direction of influence is consistent with the central bank's goals.

In light of the conclusions above, we propose the following policy recommendations: (1) The PBC should strengthen its communication with the public by delivering information regarding past and anticipated macroeconomic conditions and monetary policies. This would enhance public comprehension of the macroeconomic environment, the central bank's goals, and policy actions, thereby guiding public expectations and spending behavior. (2) Central bank communication should be as clear as possible, providing more specific policy measures and relevant data. If the PBC struggles to offer definitive forward-looking commitments or forecasts owing to multiple objectives and the necessity of maintaining credibility, it should minimize vague forward-looking communications and concentrate on providing clear retrospective communications. (3) The central bank should pay more attention to communication with groups prone to modify expectations and behavior in line with policy objectives, such as individuals who are less attentive to financial news, to improve the efficacy of the communication to a greater extent. (4) To better assess the effectiveness of the central bank's expectation management and make timely policy adjustments, it is recommended that relevant Chinese authorities conduct surveys that regularly track residents' expectations about the macroeconomy. Examining the impact of central bank communication on public expectations is the most direct way to evaluate the effectiveness of central bank expectation management, and such research relies on accurately measuring public expectations. Currently, data on residents' expectations in China primarily come from the quarterly Urban Depositors Questionnaire Survey conducted by the PBC's Department of Investigation and Statistics. Nonetheless, the frequency of these surveys is low, and only aggregated indices rather than specific data on individual expectations are published. Developed countries often use survey-based expectation data to evaluate the effectiveness of expectation management (Guo et al. 2023), and their experience may serve as a reference for the PBC.

Future research will be expanded in the following areas. First, we need to examine the effectiveness of central bank communication using a broader sample to enhance the external validity of the quantitative conclusions in the study. Second, we will develop various types of communication materials based on existing central bank communications to further explore which communication content is more effective in guiding individual expectations. For instance, we will design materials where the only difference between the reading materials for the treatment and control groups lies in readability or visibility. Third, additional questions related to demographic characteristics will be introduced to explore the heterogeneity of the effectiveness of central bank communication, which can help the PBC communicate more targetedly. Fourth, we will conduct a comparative study of the impact of various central bank communication channels through a randomized controlled experiment, such as official statements, traditional media, and online media.

Author Contributions

Yuying Jin: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Sunyao Xia: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, software, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from the Major Program of the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 21&ZD082) “Theoretical and Experimental Research on Cross-cycle Design and Adjustment of Macro-regulation in China from the Perspective of the New Development Paradigm” and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities from Shanghai University of Finance and Economics (No. CXJJ-2023-416) “Exchange Rate Expectation Management, RMB Exchange Rate, and Firm Export.” The authors also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions. All remaining errors are our own.

Ethics Statement

This study involved an anonymous survey in which participants voluntarily took part after providing informed consent. The study did not involve any personally identifiable information or sensitive data, and no deception was used.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.