Export creation of the Belt and Road Initiative: “Give-them-a-fish” or “Teach-them-to-fish”?

Abstract

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) initiated by China in 2013 is a new experiment in regional cooperation, which aims to improve infrastructure connectivity through investment. This paper investigates whether the BRI created exports for its member states (excluding China), based on a difference-in-differences model. We find a significant causal relationship between the signing of the initiative and the export growth of its member states. In addition to the large export creation between the BRI countries and China (considered as “give-them-a-fish”), export creation also originated from the BRI countries excluding China (“teach-them-to-fish”). Both the intensive and extensive margins are significantly important, indicating that export creation has not just come from expansion of the volume of existing products, but also from new products and new markets. The BRI achieved the goal of mutual benefit mainly through enlisting investment in both publicly funded infrastructure sectors and private sectors. Moreover, the initiative has enhanced the position and participation of its member states in the global value chain.

1 INTRODUCTION

The Belt and Road Initiative1 (BRI), unveiled by China's President Xi Jingping in 2013, is a regional cooperation initiative across Asia, Europe, and Africa based on bilateral and multilateral agreements, which aims to provide investment facilitation and reduce cross-border trade costs. The Belt and Road regions account for approximately 64% of the world's population and 30% of the world's gross domestic product (GDP) (Huang, 2016). The consensus is that the initiative has become an important part of China's reform and opening up, as well as its national development strategy. Although it has been proposed and pushed forward by China, the BRI is open and inclusive, and it is expected to make a positive step forward in promoting free trade in the face of the backlash of antiglobalization.

With a large number of agreements between China and the countries along the BRI routes, it is natural that the initiative would boost China's overseas direct investment and trade, which are the two major tasks of the initiative (Cheng, 2016). However, whether it has benefited the BRI member states' exports is still unclear.2 There is a Chinese proverb that asks, “give-them-a-fish” or “teach-them-to-fish”? This paper aims to examine whether the initiative has achieved the goal of “shared benefits”3 in terms of trade. That is, has the initiative improved the export capacity of BRI countries (“teach-them-to-fish”), rather than just expanding trade between China and other BRI countries (“give-them-a-fish”)? Moreover, we investigate whether the BRI has exerted a spillover effect on global trade. As indicated by Caliendo and Parro (2015), the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) mainly created trade within the area and even diverted trade from countries outside the agreement. We expect that the BRI can outperform the free trade areas (FTAs) in terms of trade creation, and create trade both within and outside the region.

We employ a difference-in-differences (DID) regression model to examine whether the initiative expanded the exports of countries along the routes, based on a sample of 191 countries from 2008 to 2019. To eliminate the influence of sample bias between the treatment group (BRI countries) and the control group (non-BRI countries), we further use propensity score matching (PSM) algorithms to match the two groups. By comparing changes in the exports of BRI countries with those of non-BRI countries after the signing of the initiative, we find that joining the BRI led to a 20.2% increase in the exports of its member states. This finding is robust when using different PSM algorithms.

We further investigate the origins of the export creation. The BRI not only strengthened trade connections between China and the BRI members but also expanded the export capacity of the member countries. Compared with non-BRI countries, BRI countries exported more to the BRI countries other than China through signing onto the BRI. Furthermore, much of the expansion came from exports to countries along the BRI routes, and there is no evidence of trade diversion from non-BRI countries to BRI countries. This reflects that the BRI boosted export vitality within the area. Moreover, the BRI is indeed open and inclusive, creating new trade rather than diverting trade from non-BRI countries to BRI countries.

Considering the huge export creation from China and the availability of data at the product level, we employ China's import data at the product level to examine export creation on both the intensive and extensive margins. We find that the BRI not only boosted exports of products that existed consistently throughout the sample period but also was conducive to the development of new products, as well as exploration of new markets.

We further explore potential channels for the BRI's export creation. By regressing total investment (logarithm) on the interaction term of interested, we find that there was a positive causal relationship between joining the BRI and total investment. Concretely, the BRI played a positive role in boosting infrastructure capacity, represented by electricity access, internet access, length of railways, container port traffic, and air transport freight. Moreover, private investment in BRI countries improved relative to that of non-BRI countries, due to the spillover effects of foreign investment and infrastructure construction. Improvement in both infrastructure and private investment contributed to the expansion of the export capacity of the BRI countries.

After it is confirmed that the initiative expanded the total exports of its member states, another question that arises is whether the BRI members also performed better in the global value chain (GVC). We employ the indices of GVC position and GVC participation proposed by Koopman et al. (2010), to measure countries' GVC performance. The findings show that the BRI helped its member states move up the GVC by improving their GVC position and GVC participation.

Studies have shown that national borders are harmful to trade through a combination of social and economic factors (Anderson & van Wincoop, 2003), while infrastructure connectivity can reduce the costs of trade (e.g., transport cost and customs clearance cost) and benefit cross-border trade (Bougheas et al., 1999; Limao & Venables, 2001; Limao & Venables, 2003; Martin & Rogers, 1995; Martincus et al., 2014; Martinez-Zarzoso & Nowak-Lehmann, 2003; Vigil & Wagner, 2012). A large literature investigates the effect of the BRI on China's economy because China is the sponsor of the initiative and its most important investor. The BRI has boosted outward foreign direct investment (FDI) and reduced financial constraints on related enterprises (Du & Zhang, 2018; Lv et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019), expanded export ability, and accelerated industrial upgrading and green development in China (Lin & Bega, 2021; Liu & Xin, 2019; Wang & Lu, 2019).

We focus on the member states that have signed the initiative, rather than just on China. In several aspects, our study differs from the existing literature, which examines trade gains and welfare changes of the member countries (Herrero & Xu, 2017; Jackson & Shepotylo, 2021; Ramasamy & Yeung, 2019; Zhai, 2018). First, we provide evidence that the BRI has achieved its goal of mutual benefit. It has taught other countries to “fish,” that is, the BRI has helped to expand the export capacity of member states both intensively and extensively, and promoted their position and participation in the GVC. Second, we show that the export expansion of member countries has come from newly created export capacity due to reduced export barriers, rather than a zero-sum game dominated by trade diversion. Third, we further explore the potential channels. In addition to the well-known channel of infrastructure investment, the initiative has exerted a spillover effect on private investment in the host countries, which has enhanced export capacity.

Our paper is also related to studies investigating the impacts of FTAs on trade creation, welfare improvement, and economic growth (Baier & Bergstrand, 2007; Caliendo & Parro, 2015; Egger et al., 2011; Grossman & Helpman, 2002; Yang & Martinez-Zarzoso, 2014). We show that the BRI outperforms the FTAs in terms of trade creation through export creation rather than export diversion. Compared with tariff reduction and removal of quantitative restrictions in FTAs, the improved connectivity among BRI countries has created trade through reduction of nontariff barriers, such as the costs of transportation, communication, and customs clearance.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides background on the BRI initiative and its potential effect on trade. Section 3 presents the details of the estimation strategy and the data used. Section 4 verifies the export creation of the BRI and discusses its origins, intensive and extensive margins, as well as the channels. Section 5 examines the effect of the BRI in boosting the GVC position and participation of its member states. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2 THE BRI AND POTENTIAL EXPORT CREATION

The creation of the BRI was a new experiment in regional cooperation based on bilateral and multilateral agreements, announced by China in 2013. It includes the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, covering most of the countries in Asia, Europe, and Africa. China had signed cooperation agreements with 17 countries by the end of 2015,4 which expanded to around 200 cooperation documents with 147 countries and 32 international organizations at the end of 2021, based on this cooperation initiative. It is a vital development strategy for China and further deepens China's reform and opening up. Although it was proposed and pushed forward by China, the initiative is open and inclusive and benefits both China and the countries along the routes through reducing various trade barriers.

The primary element of the initiative is infrastructure connectivity.5 Specifically, the initiative aims to build a connective and efficient Asia-Europe market through six overland corridors,6 which will boost trade connections along the corridors through connectivity improvements in transportation, financing, currencies, and policies. China has an overwhelming advantage in infrastructure construction, which is just what the other Belt and Road countries lack. Infrastructure connectivity has also gained strong support through several other sources, such as the Silk Road Fund and the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank. A range of cross-border projects has also been implemented, including road traffic infrastructure, energy infrastructure, communications network infrastructure, and ports. For instance, the China-Europe Railway Express connected more than 108 cities in 16 European countries by the end of 2019, with a total of 13,000 trains carrying more than 1.1 million 20-foot equivalents of goods. It has become one of the most important logistics along the routes. The convenience of customs clearance has also improved significantly, with the average inspection rate and customs clearance time decreased by 50% (World Bank, 2019). Improvement in infrastructure connection has greatly reduced the cost of trade and improved trade facilitation, both of which were expected to increase trade within the region, as well as trade between the region and other countries. The corridors were expected to boost the trade of the related countries by 2.8 to 9.7 percentage points (World Bank, 2019).

The construction of the BRI also encouraged the growth of private investment from China and other countries (Du & Zhang, 2018). FDI in BRI countries increased rapidly, accounting for 20% of global total in 2017, which was much higher than that (less than 10%) in 2000 (Chen & Lin, 2018). More importantly, FDI can produce spillover effects on local workers' skills, innovation, productivity, and production complexity (Javorcik et al., 2018; Javorcik, 2004; Liu et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2017; Zhang, 2017), which are conducive to the expansion of exports of host countries along the routes.

The BRI fills the gap in the construction of FTAs in the Asian area and accelerates the economic integration of related countries. It differs from FTAs in the following aspects. FTAs enhance trade through the elimination of tariffs and quantitative restrictions among member states, while the BRI is a regional cooperation initiative, which provides trade facilitation through various channels of cooperation related to economic, political, cultural, and other aspects. As stated in an official document in 2015,7 the initiative aimed to achieve win-win cooperation through policy, infrastructure, trade, financial, and people-to-people connectivity. The connectivity contributes to the facilitation of trade among Belt and Road countries. Based on this difference, it is expected that the trade creation effect may also be different between the BRI and FTAs.

3 IDENTIFICATION STRATEGY, DATA, AND VARIABLES

3.1 Identification strategy

Following the gravity model (Head & Mayer, 2014), the equation also includes a battery of time-varying covariates () related to exporting countries, such as the real GDP (logarithm), population (logarithm), urbanization rate, and bilateral real exchange rates. In addition, we use partner-year fixed effects () to control time-varying demand factors, and country-partner fixed effects () to control bilateral gravitational factors. The coefficient of the interaction term is our main variable of interest. It measures the export creation of the BRI in its member states. We expect it to be significantly positive.

3.2 Data and variables

The data and variables used in this estimation come from several sources, which are shown in Table A1. The bilateral export data are from the United Nations Comtrade database, which records detailed global trade data at the country and product levels. We use bilateral export data at the aggregate level (natural logarithm). Our sample spans from 2008 to 2019. There are 191 countries in the sample, including 113 BRI countries9 and 78 non-BRI countries. The list of BRI members and the year they signed the agreements are obtained from www.ydylcn.com. Exports of countries in the sample accounted for about 79% of global total exports in 2013. Moreover, we use China's import data with all trading partners at the Harmonized System (HS) 6-digit product level (obtained from the statistics of the General Administration of Customs in China) to explore the changes in exports on the intensive and extensive margins. We obtain the data for some of the control variables from the World Development Indicators database, including the real GDP, real bilateral exchange rate, urbanization rate, and population.

For the potential transmission channels, we further examine the impact of joining the BRI on the infrastructure investment and private investment of its member states. Total investment is represented by gross fixed capital formation. Infrastructure capacity is measured by five indicators: the proportion of the population with access to electricity in the total population, secure internet servers per 1 million people, total route kilometers of rail lines, container port traffic (billions of containers), and air transport freight (millions of ton-kilometers). Private investment is represented by private investment in the energy and transport sectors. The related data were obtained from the World Development Indicators database.

We also use the GVC position index and GVC participation index to examine whether the BRI improved members' position and participation in the GVC. These two indices are calculated following Koopman et al. (2010) and Che et al. (2020), and the data were obtained from the Trade in Value Added (TiVA) database. The GVC industries are matched to products at the HS 6-digit level using concordance tables downloaded from the World Integrated Trade Solution database.

4 “GIVE-THEM-A-FISH” OR “TEACH-THEM-TO-FISH”?

This section provides the DID estimates of the export creation of the BRI and robustness checks using PSM algorithms. Furthermore, we discuss the origins of the export creation and answer the following three questions. In which partners have exports been created? Is the export creation extensive or intensive? Is investment an effective channel of export creation?

4.1 Export creation

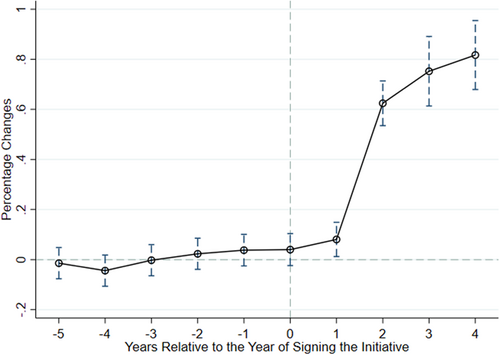

The parallel trends assumption ensures that the coefficient of the interaction term reports the export creation of the BRI in its member states. We assume that the time trends of exports in the treatment and control groups were the same before countries joined the initiative. Figure 1 shows the percentage changes in exports of BRI countries (treatment group) compared with non-BRI countries (control group) after countries signed the initiative, based on the regressions of exports on a set of year dummies. The figure provides support for our DID assumption that the time trends of the two groups were highly consistent before the agreements were signed, while they have gradually diverged since countries joined the BRI group. We attribute the enlargement of the gap between the two groups to the export creation effect of the initiative, which is estimated using the DID model.

Column 1 in Table 1 shows the baseline results. The estimated coefficient of the interaction term is positive at the 1% level of statistical significance in the regression controlling the gravity factors (logarithm of real GDP, real exchange rate, urbanization rate, and logarithm of population), as well as the exporter-partner and partner-year fixed effects. This result implies that the exports of BRI members expanded after they joined the initiative. The estimate of 0.202 indicates that the BRI led to a 20.2% increase in the exports of BRI members, compared with those of non-BRI countries. The results are in line with the findings of Maliszewska and van der Mensbrugghe (2019), who projected that infrastructure improvement in the BRI area would lead to increased exports of countries along the routes, compared with those of non-BRI countries.

| Export value (log) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| All partners | China | Partners except China | |

| Variable of interest | |||

| Silk × Post | 0.202*** | 0.582*** | 0.204*** |

| (0.0343) | (0.179) | (0.0343) | |

| GDP | 0.932*** | 0.946*** | 0.939*** |

| (0.0105) | (0.0474) | (0.0105) | |

| Real Exchange Rate | 0.00543*** | 0.0205*** | 0.00529*** |

| (0.000862) | (0.00522) | (0.000861) | |

| Population | −0.0571*** | 0.514*** | −0.0633*** |

| (0.0106) | (0.0505) | (0.0107) | |

| Urbanization Rate | 0.00575*** | 0.0362*** | 0.00549*** |

| (0.000701) | (0.00395) | (0.000702) | |

| Country × Partner FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Partner × Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 166,582 | 1,036 | 165,546 |

| R2 | 0.219 | 0.835 | 0.220 |

- Note: Silk is a dummy variable for the BRI countries, which equals 1 for BRI members (excluding China) and 0 otherwise. Post is also a dummy, which equals 1 if the country joined the initiative in year t (including the year of signing agreements), and 0 otherwise. For non-BRI countries, it always takes the value 0. Control variables are time-varying and related to exporting countries. GDP is the natural logarithm of the real gross domestic product. Real Exchanges Rate is the real effective exchange rate index based on 2010. Population is the natural logarithm of the total population. Urbanization Rate is the proportion of urban population in the total population. Column 1 is estimated on the full sample. Column 2 keeps China as the only partner, while column 3 drops China from the partner group. Standard errors clustered at the country-year level are in parentheses. *** represents statistical significance at the 1% level. Belt and Road Initiative

- Abbreviations: BRI, Belt and Road Initiative; GDP, gross domestic product.

There may exist sample bias between the treatment and control groups due to differences in economic features, which may lead to failure in identifying the causality between signing the BRI and the expansion of exports of the BRI countries. To avoid this problem, we conduct PSM algorithms to match the two groups using the means of the control variables (the logarithm of GDP, the logarithm of population, exchange rate, and urbanization rate) from 2011 to 2013. We adopted three PSM algorithms: one-to-three, radius, and kernel matching. The results in Table 2 are in line with the baseline estimates.

| Export value (log) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| One-to-three matching | Radius matching | Kernel matching | |

| Variable of interest | |||

| Silk × Post | 0.105** | 0.139*** | 0.208*** |

| (0.0492) | (0.0465) | (0.0392) | |

| Baseline Control | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country × Partner FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Partner × Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 119,895 | 140,460 | 148,191 |

| R2 | 0.208 | 0.230 | 0.199 |

- Note: Variables are the same as in Table 1. We conduct PSM algorithms to match the treatment and control groups using the means of control variables (natural logarithm of GDP, natural logarithm of population, exchange rate and urbanization rate) from 2011 to 2013. Column 1 is one-to-three matching. Column 2 is radius matching. Columns 1 to 2 are matching with 0.05 caliper. Column 3 is kernel matching. Standard errors clustered at the country-year level are in parentheses. ** and *** represent statistical significance at the 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

- Abbreviations: BRI, Belt and Road Initiative; GDP, gross domestic product; PSM, propensity score matching.

4.2 Origins of trade creation

To answer the question of “give-them-a-fish” or “teach-them-to-fish,” we examine whether the export creation stemmed from export expansion to China (“give-them-a-fish”) or to other countries (“teach-them-to-fish”). We divide the sample into two subsamples according to export destinations—exports to China and exports to countries excluding China—and re-estimate the benchmark model using the two subsamples. Columns 2 and 3 in Table 1 show the estimates.

The estimates in columns 2 and 3 are positive and significant. Column 2 reports the estimates based on the sample with China as the only partner, while column 3 reports those based on the sample excluding China from the partners. The coefficient of the interaction term in column 2 is much larger than that in column 3, reflecting that China as the main investor in the BRI is absolutely the largest source of export creation. The estimates in column 3 indicate that there are also new exports created from BRI countries to countries other than China. These findings verify that the BRI achieved the goal of mutual benefit, and it did not just “give-them-a-fish,” but also “taught-them-to-fish.” Robustness checks of the estimates in columns 2 and 3 are shown in Tables A2 and A3.

| Export value (log) | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| BRI countries | Non-BRI countries | |

| Variable of interest | ||

| Silk × Post | 0.736*** | 0.134 |

| (0.0536) | (0.102) | |

| Baseline Control | Yes | Yes |

| Country × Partner FE | Yes | Yes |

| Partner × Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 66,163 | 34,092 |

| R2 | 0.225 | 0.069 |

- Note: Variables are the same as in Table 1. Column 1 is estimated based on the sample with BRI countries as the partners (excluding China), while column 2 is based on that with non-BRI countries as the partners. Standard errors clustered at the country-year level are in parentheses. *** represents statistical significance at the 1% levels.

- Abbreviation: BRI, Belt and Road Initiative.

We further divide the trading partners (excluding China) into BRI countries and other countries and re-estimate our model. The results (Table 3) show that exports were mainly created among the BRI countries, and export creation between BRI countries and non-BRI countries was not statistically significant. There is no evidence of trade diversion from non-BRI countries to BRI countries. Trade creation among the BRI countries may come from the improvement in infrastructure connectivity and reduction in export costs, and we will test this channel later. The results are in line with the findings of Herrero and Xu (2017), who reveal that landlocked countries in the European Union had benefited more from the improvement in transport infrastructure, compared with other countries in the same area.

It is natural to compare the export creation of the BRI with that of FTAs. Caliendo and Parro (2015) find that NAFTA mainly created trade within the area. More than that, they find that there was a trade diversion from countries outside the agreement to the NAFTA members. The divergence of the BRI and NAFTA in trade creation may come from the spillover effect of infrastructure connectivity on trade among BRI countries. Unlike NAFTA, which boosts trade by reducing tariffs and quantitative restrictions, the BRI facilitates trade by improving infrastructure connectivity, hence reducing nontariff barriers, such as transportation and customs clearance costs. Reductions in nontariff barriers are more likely to produce spillover effects and thus benefit exports between BRI countries and non-BRI countries. For instance, the connectivity network along the routes not only enhances the BRI's internal links but also strengthens links between BRI countries and non-BRI countries. Therefore, the exports of BRI countries are more accessible and at a lower cost for non-BRI countries. In addition, foreign investment may play different roles in the BRI region and NAFTA. As Chen et al. (2017) document, greenfield FDI benefits domestic investment in host countries, while mergers and acquisitions do not contribute to domestic investment. The high proportion of greenfield investment in FDI in the BRI countries brings about export creation rather than export diversion.

4.3 Intensive and extensive margins

We need product-level data to explore whether export creation originates from the expansion of existing products (intensive margin) or from the expansion of product categories (extensive margin). However, it is difficult to obtain the HS 6-digit product data between countries from the Comtrade database, due to its restrictions on bulk downloads. Therefore, we use China's import data with all partners at the HS 6-digit level as an alternative. As the world's largest trading nation in goods, China has a wide range of products, which are representative of all the traded products in the world. We use data between 2010 and 2015, as well as 2019,10 to capture the export creation of BRI members on the intensive and extensive margins. Countries that signed the BRI between 2016 and 2018 are dropped from the sample, and data for 2019 provide excellent ex-post observations for the treatment group, after an interval of 4 years.

For the intensive margin, we keep products that existed consistently throughout the sample period and examine changes in exports between the BRI and non-BRI countries. Columns 1–3 in Table 4 report the results. The control variables are the same as in the benchmark model, and fixed effects at the product-year and country-year levels are included. The estimates are all significant at the 1% level of statistical significance. They confirm the existence of export creation on the intensive margin, with the coefficients of the interaction term being positive for quantity (log) and negative for price (log). The increase in export value and the decline in prices show that the initiative expanded the export supply of its member states. The infrastructure connectivity created a unified, large market, which has been conducive to increased export supply through cost reductions in production and transportation.

| Intensive | Extensive | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Export value (log) | Export quantity (log) | Export price (log) | Product number | Partner number | |

| Variable of interest | |||||

| Silk × Post | 0.201*** | 0.280*** | −0.0810*** | 60.37** | 3.641*** |

| (0.0320) | (0.0411) | (0.0277) | (25.74) | (1.226) | |

| Baseline control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Product × Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 293,662 | 292,305 | 292,305 | 334 | 1,056 |

| R2 | 0.099 | 0.132 | 0.182 | 0.997 | 0.983 |

- Note: The data used are export data of all trading partners to China at the HS 6-digit product level, which is counted by China's General Administration of Customs. We use data between 2010 and 2015, as well as 2019. We drop countries that signed the initiative between 2016 and 2018. For the intensive margin, we keep products that existed consistently throughout the sample period. Other variables are the same as in Table 1. Standard errors clustered at the country-year level are in parentheses. ** and *** represent statistical significance at the 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

- Abbreviation: HS, Harmonized System.

The cost of entry may also have been reduced through stronger connectivity among the BRI members, in terms of both export partners and products. Column 4 in Table 4 shows the estimates for the number of products. Fixed effects at the country and year levels help to capture variations in the number of export products. The estimate is significantly positive, providing strong evidence that the BRI reduced entry costs for its members' products. We further estimate export creation in terms of trading partners based on the aggregate export data of all countries, to examine whether the BRI contributed to exploring new markets. The estimates in column 5 confirm this at the 1% level of statistical significance.

4.4 Channels

We explore potential channels for the BRI's export creation. In addition to its direct impact on exports, the BRI may indirectly contribute to export expansion by boosting investment. We first examine the effect of the BRI on the total investment (represented by fixed capital formation) of its members, by controlling a range of variables at the country-year level, as well as year and country-fixed effects. The results in Table 5 confirm the positive (at the 1% level of statistical significance) causal relationship between joining the BRI and total investment. Next, we examine the channels of infrastructure investment and private investment separately.

| (1) | |

|---|---|

| Investment (log) | |

| Variable of interest | |

| Silk × Post | 0.120*** |

| (0.0308) | |

| Population (−1) | 0.972*** |

| (0.223) | |

| Urbanization Rate (−1) | 0.0185** |

| (0.00793) | |

| M2 (−1) | 0.00318*** |

| (0.000868) | |

| Export Ratio (−1) | −0.00300** |

| (0.00123) | |

| Interest Ratio (−1) | −0.00463*** |

| (0.00106) | |

| Year FE | Yes |

| Country FE | Yes |

| Observations | 1229 |

| R2 | 0.997 |

- Note: Silk and Post are the same as in Table 1. Investment is the gross fixed capital formation. Control variables are related to exporting countries and one period lagged. Population is the natural logarithm of growth rate of total population. Urbanization Rate is the proportion of urban population in total population. M2 is the growth rate of Broad Money. Export Ratio is the share of export in GDP. Interest Ratio is the effective interest rate. Standard errors clustered at the country-year level are in parentheses. ** and *** represent statistical significance at the 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

- Abbreviations: BRI, Belt and Road Initiative; GDP, gross domestic product.

4.4.1 Infrastructure investment channel

Infrastructure investment contributes to the construction of the connectivity network. Infrastructure promotes trade through reducing trade costs. In particular, infrastructure was the bottleneck restricting the development of trade among the Belt and Road countries before 2013. Since the announcement of the initiative, infrastructure connectivity has been the main focus and has been greatly improved. The China-Europe Railway Express has experienced rapid growth in transport capacity, and it has become one of the most important logistics along the routes. The convenience of customs clearance has also improved significantly, with the average inspection rate and customs clearance time decreased by 50%. We will examine whether the improvement in infrastructure is from the signing of the BRI.

We use five indicators related to infrastructure capacity to capture the effect of infrastructure investment and examine whether the improvement in infrastructure capacity came from signing the BRI. The five measures of infrastructure capacity are the proportion of the population with access to electricity (electricity access), secure internet servers per 1 million people (internet access), length of railways (total route-kilometers of rail lines), container port traffic, and air transport freight. The results in Table 6 indicate that the BRI has boosted the infrastructure capacity of its member states, with electricity access, length of railways, and container port traffic significantly improved.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity access | Internet access | Length of railways | Container port traffic | Freight of air transport | |

| Variable of interest | |||||

| Silk × Post | 2.596*** | 74.45 | 947.5** | 160,347* | −9.056 |

| (0.425) | (1,205) | (376.3) | (87,025) | (51.22) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country × Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 2644 | 2169 | 804 | 1944 | 1844 |

| R2 | 0.975 | 0.337 | 0.990 | 0.980 | 0.964 |

- Note: Electricity access is represented by the proportion of total population with access to electricity in total population. Internet access is the secure internet servers per 1 million people. Length of railways is the total route-kilometers of rail lines. Container port traffic is taking 20-foot equivalent as unit. Freight of air transport is taking million ton-km as unit. Other variables are the same as in Table 5. Standard errors clustered at the country-year level are in parentheses. *, **, and *** represent statistical significance at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

- Abbreviation: BRI, Belt and Road Initiative.

4.4.2 Private investment channel

Export creation may also arise from the increase in private investment. Infrastructure connectivity was the main task of the BRI, and it may further benefit local private investment through improvement in transport facilities, entrepreneurs' confidence, and export opportunities brought by connectivity. Moreover, related studies show that the crowding-in effect mainly arises from greenfield investment, rather than mergers and acquisitions (Chen et al., 2017). As the sponsor and primary investor in the BRI, greenfield investment accounts for the vast majority of China's total investment in the BRI region (Lv et al., 2019).11 For these reasons, we infer that the BRI has spurred private investment in the BRI countries, providing another crucial channel for export creation.

In addition to gross fixed capital formation in the private sector, we use two sub items of private investment: private energy investment and private transport investment. Table 7 shows the estimates. The coefficient for the growth rate of fixed capital formation (in the private sector) in column 1 is positive and significant at the 10% level of statistical significance, indicating that the BRI exerted spillover effects on private investment. The coefficient of the term of interest for transport investment is positive and significant at the 1% level of statistical significance, and that for energy investment is positive although not significant. Overall, the BRI has been conducive to investment in the private sector and significantly boosted private investment, especially transport investment.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Private investment | Private transport investment (log) | Private energy investment (log) | |

| Variable of interest | |||

| Silk × Post | 0.113* | 1.240*** | 0.0574 |

| (0.0597) | (0.455) | (0.323) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 630 | 168 | 369 |

| R2 | 0.211 | 0.690 | 0.649 |

- Note: Private investment is the growth rate of gross fixed capital formation in the private sectors. Private energy investment and private transport investment are private investment (natural logarithm) in energy and transport sectors. Other variables are the same as in Table 5. Standard errors clustered at the country-year level are in parentheses. * and *** represent statistical significance at the 10% and 1% levels, respectively.

- Abbreviation: BRI, Belt and Road Initiative.

5 MOVING UP THE GLOBAL VALUE CHAIN

So far, we have confirmed the export creation effect of the BRI in its member states, and we wonder whether there was also an improvement in their GVC performance. According to the TiVA statistics, foreign value added embodied in the exports of the BRI members was 24% in 2015, 4 percentage points low er than in 2000. This reflects the improvement in export capacity and participation in the GVC. We expect that the BRI accelerated this process.

We define and calculate the GVC position index and GVC participation index for all the countries in our sample, according to Koopman et al. (2010). The details of these two indices are described in our previous paper (Che et al., 2020). Based on the decomposition of the value added of exports, GVC position is measured by the relative value of participation in the upstream and downstream of the GVC, with a positive value for upstream participation (raw materials) in a specific industry and a negative value for downstream participation (final goods).

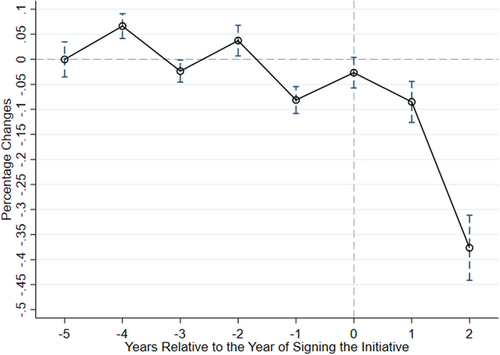

Figure A1 shows the difference in estimated coefficients between the BRI countries (treatment group) and non-BRI countries (control group), based on the regressions of GVC position on a set of year dummies. It confirms that the time trends of the two groups were consistent before the agreements were signed, and they have diverged significantly since countries signed the initiative. We further employ the same DID framework (Equation 1) to estimate the effect of the BRI on its members' GVC position. Column 1 in Table 8 reports the results. The coefficient of the term of interest is negative and significant at the 1% level of statistical significance, indicating that the BRI led to upgrading exports, moving from upstream (dominated by raw materials) to downstream with improvement in product complexity and value added.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Position | Participation | |

| Variable of interest | ||

| Silk × Post | −0.110*** | 3.870*** |

| (0.00899) | (0.272) | |

| Baseline Control | Yes | Yes |

| Country FE | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 109,794 | 109,794 |

| R2 | 0.240 | 0.207 |

- Note: GVC position and participation index are calculated at the country-sector level following Koopman et al. (2010), using the trade value added data obtained from the TiVA database. Other variables are the same as in Table 1. Standard errors clustered at the country-year level are in parentheses. *** represents statistical significance at the 1% level.

- Abbreviation: BRI, Belt and Road Initiative; GVC, global value chain.

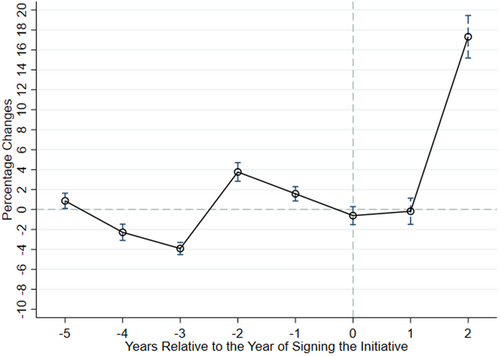

GVC participation reflects the intensity of a country's participation in a sector in the GVC, and we expect that the BRI enhanced the GVC participation of its member states. Accordingly, Figure A2 verifies the parallel trends assumption and column 2 in Table 8 shows the estimates related to the GVC participation index, with basic controls and fixed effects at the country and year levels. The estimated coefficient is significantly positive, implying that the BRI caused deeper participation in the GVC for its members and strengthened the trade links between the BRI countries and non-BRI countries. This finding is consistent with that of Zhang et al. (2021), who show that free trade agreements benefit exports in both simple and complex value chains.

6 CONCLUSION

We have examined the export creation of the BRI in its member states, based on a DID strategy. We found that signing the BRI boosted the exports of its members by 20.2%, compared with the non-BRI countries. Our results are robust when using PSM algorithms to match the treatment group (BRI countries) and control group (non-BRI countries). Export creation mainly came from China (considered as “give-them-a-fish”), which is the sponsor and main investor in the initiative. Export creation also originated from the BRI countries other than China (expansion of export capacity, which is “teach-them-to-fish”), and there was no evidence of export diversion from non-BRI countries to BRI countries. Both the intensive and extensive margins contributed to the export expansion of the BRI member states. We explored the investment channels for the BRI's export creation and found that the BRI exerted significant spillover effects on infrastructure capacity and private investment, both of which are conducive to export creation. Furthermore, joining the initiative was conducive to moving up the GVC (measured by GVC position and participation) for the BRI members.

Infrastructure connectivity was the primary task of the BRI and the main reason behind the export creation. The connectivity along the BRI routes is ongoing, and it is expected that the export creation of the BRI will be further enhanced in the long run.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Yu Chen: data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; software. Yan Zhang: conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology; project administration; supervision; validation; visualization. Lin Zhao: conceptualization; formal analysis; validation; visualization; writing–original draft; writing–review & editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Yan Zhang gratefully acknowledges support from the Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, Grant Nos. 71703085 and 72073095).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

None declared.

APPENDIX A

See Table A1–A3 and Fig. A1 and A2.

| Variables | Source | Obs. | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Export value (aggregated, log) | 1 | 281,013 | 15.02 | 4.175 |

| GDP (log) | 3 | 275,904 | 25.31 | 2.046 |

| Real exchange rate | 3 | 170,349 | 99.40 | 10.80 |

| Population (log) | 3 | 278,059 | 16.26 | 1.849 |

| Urbanization rate | 3 | 278,059 | 63.39 | 22.00 |

| Export value (HS 6-digit product level, log) | 2 | 564,165 | 11.25 | 3.709 |

| Export quantity (log) | 2 | 552,133 | 7.877 | 4.401 |

| Export price (log) | 2 | 552,133 | 3.502 | 2.902 |

| Product number | 2 | 815 | 692.2 | 1,132 |

| Partner number | 2 | 2028 | 138.6 | 63.55 |

| GVC position | 4 | 25,232 | −2.710 | 0.717 |

| GVC participation | 4 | 25,232 | 30.12 | 14.77 |

| Investment (log) | 3 | 2081 | 25.88 | 3.410 |

| Broad Money (M2) | 3 | 1879 | 12.85 | 12.79 |

| Export Ratio | 3 | 2292 | 44.54 | 33.39 |

| Interest Ratio | 3 | 1599 | 6.299 | 8.670 |

| Electricity access | 3 | 6755 | 80.65 | 28.88 |

| Internet access | 3 | 2861 | 4544 | 22,992 |

| Length of railways | 3 | 2036 | 9931 | 23,818 |

| Container port traffic | 3 | 3132 | 28.69 | 79.94 |

| Freight of air transport | 3 | 9344 | 3804 | 15,027 |

| Private energy investment (log) | 3 | 1430 | 20.46 | 2.499 |

| Private transport investment (log) | 3 | 860 | 20.53 | 2.299 |

| Private investment | 3 | 2980 | 0.317 | 3.043 |

- Sources: (1) United Nations Comtrade database, (2) The statistics of the General Administration of Customs in China, (3) World Development Indicators database, and (4) Trade in Value Added (TiVA) database & The World Integrated Trade Solution database.

| Export value (log) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| One-to-three matching | Radius matching | Kernel matching | |

| Variable of interest | |||

| Silk × Post | 0.527* | 0.574* | 0.636*** |

| (0.294) | (0.298) | (0.236) | |

| Baseline Control | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country × Partner FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Partner × Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 761 | 904 | 940 |

| R2 | 0.797 | 0.810 | 0.802 |

- Note: Robustness check of column 2 in Table 1. Variables are the same as in Table 1. We conduct PSM algorithms to match the treatment and control groups using the means of control variables (logarithm of GDP, logarithm of population, exchange rate and urbanization rate) from 2011 to 2013. Column 1 is one-to-three matching. Column 2 is radius matching. Columns 1 and 2 are matching with 0.05 caliper. Column 3 is kernel matching. Standard errors clustered at the country-year level are in parentheses. * and *** represent statistical significance at the 10% and 1% levels, respectively.

- Abbreviations: BRI, Belt and Road Initiative; GDP, gross domestic product; PSM, propensity score matching.

| Export value (log) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| One-to-three matching | Radius matching | Kernel matching | |

| Variable of interest | |||

| Silk × Post | 0.104** | 0.134*** | 0.206*** |

| (0.0494) | (0.0464) | (0.0392) | |

| Baseline Control | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country × Partner FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Partner × Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 119,134 | 139,556 | 147,251 |

| R2 | 0.209 | 0.231 | 0.200 |

- Note: Robustness check of column 3 in Table 1. Variables are the same as in Table 1. We conduct PSM algorithms to match the treatment and control groups using the means of control variables (logarithm of GDP, logarithm of population, exchange rate and urbanization rate) from 2011 to 2013. Column 1 is one-to-three matching. Column 2 is radius matching. Columns 1 and 2 are matching with 0.05 caliper. Column 3 is kernel matching. Standard errors clustered at the country-year level are in parentheses. ** and *** represent statistical significance at the 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

- Abbreviations: BRI, Belt and Road Initiative; GDP, gross domestic product; PSM, propensity score matching.

REFERENCES

- 1 The Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road.

- 2 The BRI member states (or the BRI countries) in the following text refer to the BRI countries excluding China, unless otherwise specified.

- 3 As stated by President Xi Jinping in March 2015, at the Boao Forum.

- 4 In late March 2015, a special leading group was established to promote the initiative. Meanwhile, the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of Commerce jointly issued a paper, “Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road.” Since then, the development of the initiative has been accelerated.

- 5 It was stressed by the Third Plenum of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China in November 2013.

- 6 The six overland corridors are China-Pakistan, New Asia-Europe Land Bridge, China-Mongolia-Russia, China-Indochina-Peninsula, Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar, and China-Central Asia-West Asia.

- 7 The “Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road.”

- 8 In addition, including China as a country in the treatment group may drive the estimation results due to the country's huge exporting capability.

- 9 As of our sample time, 2019, there were 113 BRI member states. Some of them are not included in the sample due to lack of data.

- 10 Due to the lack of data for 2016–2018, we use data for 2019 to estimate export creation at the HS 6-digit product level.

- 11 Lv et al. (2019) indicate that the proportion of mergers and acquisitions in China's total outward FDI in BRI countries was less than 11% during 2015–2017. Therefore, greenfield investment dominates China's investment in the BRI countries.