Prevalence and Correlates of Behavioural Risk Factors for Non-Communicable Diseases Among Allied Health Undergraduate Students in Ghana: A Cross-Sectional Study

ABSTRACT

Background and Aim

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are noninfectious diseases mostly marked by complex aetiology with different risk factors. They develop from an interplay between modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors, which are of great concern to the public as they mostly lead to varied metabolic changes. This study assessed the prevalence and correlates of behavioural risk factors of non-communicable diseases among undergraduate allied health students in Ghana.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study that used a pretested and structured questionnaire to collect data from 228 participants. The data was analysed using SPSS. Logistic regressions and Chi-squared tests were employed to assess the associations between sociodemographic factors and each NCD risk factor. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

About 87.3% of undergraduate allied health students practised unhealthy dietary patterns. Only 45.2% were physically active. Being a Nonresident student was associated with drinking alcohol (OR = 2.5; 95%CI = 1.1–5.9). Male undergraduate students were less likely to be physically inactive (OR = 0.4; 95%CI = 0–0.9) while community nutrition students were less likely to engage in unhealthy diet practices (OR = 0.7; 95%CI = 0.2–1.3). Female proportions among those with one (60.7%, p = 0.02) and two (61.9%, p = 0.01) risk factors were high. A greater portion of the students with unhealthy dietary (81.4%, p = 0.032) and physical inactivity (69.5%, p = 0.010) patterns were 18-24 years old. Most participants with one (61.8%, p = 0.04) and two (69.5%, p < 0.001) behavioural risk factors were all 18–24 years old.

Conclusion

The findings of this study highlight a concerning trend of poor dietary habits and physical activity patterns among undergraduate allied health students. Despite being future healthcare professionals, these students exhibited suboptimal behaviours that can negatively impact their own health and well-being, as well as their ability to provide effective health promotion and education to their future patients. Healthcare educators and administrators should recognize the importance of promoting a healthy campus environment that supports students' physical and mental well-being.

1 Background

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are noninfectious diseases that cannot be transmitted from one person to another [1]. They are mostly marked by complex aetiology and have different risk factors [2]. The most common NCDs include cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes, and respiratory diseases [3]. These diseases develop from an interplay between modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors. The modifiable risk factors include unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, tobacco use, and harmful alcohol use while the non-modifiable risk factors include age, sex, race, and genetic factors [4]. The modifiable risk factors of non-communicable diseases are of great concern to the public as they mostly lead to varied metabolic changes such as obesity, high blood glucose levels, high cholesterol levels, and high blood pressure [4]. Although global action has been adopted by the World Health Organization (WHO) to reduce the detrimental effects of behavioural risk factors for non-communicable diseases, the negative health implications of these behavioural risk factors remain high [1].

In 2019, the WHO reported that harmful alcohol use accounts for an estimated number of 2.6 million mortalities and 400 million morbidities [5]. Furthermore, the mortalities and morbidities caused by harmful alcohol use exceeded those caused by various diseases such as tuberculosis, diabetes and HIV/AIDs [6]. Tobacco use also accounted for approximately 9 million deaths globally with an estimated number of 2.2 million adults smoking tobacco daily in 2019 [7]. Physical inactivity as another modifiable risk factor accounts for about 6% of worldwide fatalities and has been noted as the primary cause of about 27% of diabetes, 30% of ischaemic heart diseases, and 21–25% of breast cancer. Inadequate intake of fruits and vegetables has been reported to contribute to approximately 31% of ischaemic heart diseases as well as 11% of strokes globally [8].

The prevalence of harmful alcohol consumption, smoking and physical inactivity has been reported as 65.1%, 22.9%, and 57.4% respectively by Monteiro et al., in Brasilia [9]. In India, a study conducted by Yogesh et al., among undergraduate medical students in Western Gujarat revealed that 63% of the participants were physically inactive while 85% had low fruit and vegetable intake [10]. In another study by Dahal et al., the frequent behavioural risk factors of non-communicable diseases were smoking, alcohol consumption, low fruit and vegetable consumption, and low physical activity [11].

- 1.

To assess the prevalence of behavioural risk factors of NCDs among undergraduate allied health students.

- 2.

To determine the co-occurrence of behavioural risk factors of NCDs among undergraduate students.

- 3.

To assess any associations of behavioural risk factors and concurrence of risk factors with socio-demographic characteristics.

- 4.

To determine the correlates of behavioural risk factors of NCDs among undergraduate allied health students.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design, Population, and Site

This was a cross-sectional prospective study among undergraduate students at Klintaps University College of Health and Allied Sciences (KCOHAS). KCOHAS is a leading private institution situated in Ghana and the premier fully private university college of health and allied sciences in West Africa offering programmes such as Medical Laboratory Science, Community Nutrition, Clinical Dietetics, Diagnostic Medical Sonography, Medical Imaging Science (Radiography), Public Health, Medicine, and Ophthalmic Dispensing.

2.2 Inclusion Criteria

- 1.

Undergraduate students at Klintaps University College who were 18 years and above.

- 2.

Undergraduate students who consented and were willing to participate.

2.3 Exclusion Criteria

- 1.

Undergraduate students who were below 18 years.

- 2.

Undergraduate students who did not consent to participate in the study.

2.4 Sampling Technique and Sample Size

s = Sample size

N = Population size

e = acceptable sample error = 0.05

X2 = Chi-squared of degree of freedom 1 and confidence 95% = 3.841

Therefore, the sample size used for this study was 228 participants.

2.5 Data Collection Instrument and Data Collection

An online survey using Google Forms (Google, Mountain View, California) was designed. The questionnaire was designed based on relevant literature and study objectives. The questionnaire assessed the socio-demographic characteristics such as age, sex, and religion, and behavioural risk factors of the participants such as physical activity, alcohol consumption, smoking, and unhealthy dietary patterns. The participants were asked to indicate their readiness to participate (consent) in the survey after receiving a brief overview of the study's aims, objectives, risks, and benefits on the first page of the questionnaire. Additionally, participants were reminded that they could leave the research at any moment. The participants were then informed to complete and submit only one questionnaire response, which was also guaranteed by Google Forms' in-built security protocols. A pre-testing of the questionnaire was done among 20 undergraduate students from the Narh-Bita College to assist in restructuring and logical flow of questions in the questionnaire. The questionnaire was developed from previous studies on behavioural risk factors for non-communicable diseases with good validity [8, 9, 12-14]. Cronbach's alpha was used to assess the questionnaire's reliability, and the results indicated a significant coefficient of reliability (Cronbach's alpha: 0.83).

2.6 Data Analysis and Study Variables

The data was entered into Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 (IBM Inco, USA) and Microsoft Excel 2016 and was then double-checked to remove all invalid points. The data collected was represented in percentages for easy understanding. Participants who had engaged in less than 30 min of moderately to vigorously intense physical activity daily were classified as physically inactive [16]. Physical activities included running, jogging, playing football, and walking or riding a bicycle to school [17]. Participants were classified as having an unhealthy diet if they consumed less than five servings of fruit and vegetables and more than 5 grams of salt or 2 grams of sodium in a day [18]. These were determined by the recall of physical activity, as well as fruit and vegetable intake in the last 12 h [17, 18]. Furthermore, participants who currently smoke tobacco were classified as current tobacco smokers [17]. The term “current use of tobacco” refers to the daily or irregular use of one or more smoked or smokeless tobacco products in the last 30 days preceding the survey [17]. Participants who consumed alcohol in the previous 30 days were classified as current drinkers [13]. These were also determined by the recall of tobacco and alcohol consumption in the last 1 month. The ages of the participants were categorised as “18–24 years”, “ 25–29 years”, and “30–35”, whereas sex was classified as “male” and “female”. Resident participants refer to students in hostel facilities provided and managed by the University (KCOHAS). Chi-squared test was employed to test for possible association between socio-demographic characteristics (age and sex) and the behavioural risk factors and the concurrence of risk factors after checking that the data was not significantly skewed. The variables used for the Chi-squared test were categorical. Once the models' goodness of fit test conditions were satisfied, we employed logistic regressions to assess the associations between sociodemographic factors and each NCD risk factor. The residuals from the regression analysis were examined for autocorrelation using the Durbin–Watson test statistic for the independence of errors. To measure each observation's impact, Cook's distance was computed. Using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of fit (p = 0.08), the model's fitness was evaluated. An analysis of multicollinearity was conducted using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF = 2). The multivariable logistic regression model was fitted to the screened variables using a backward stepwise method to reduce the influence of confounders and identify the independent effects of each variable on the outcome variable. We computed odds ratios (ORs) with a 95% confidence interval [CI]. In all analyses, a 2-sided p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant for the study.

2.7 Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval was obtained from the Klintaps University College of Health and Allied Sciences Ethical Review Committee with the number KCOHASERC/EC/2023/37. All the respondents consented before participation. The study complied with the Helsinki Declaration.

3 Results

The majority of the participants were 18–24 years old (77.2%), while the smallest proportion (9.6%) were aged 25–29 years. Most of the participants were females (64.9%). The majority of undergraduate students (26.8%) were radiography students. Only 6.6% were ophthalmic dispensing students. Table 1 provides a detailed overview of the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants. A greater proportion of the undergraduate allied health students (87.3%) in this study had inadequate intake of fruit and vegetables. About 80.7% of them consumed > 5 g of salt in a day while 19.3% consumed < 5 g of salt in a day. More than one-quarter (26.3%) of the participants stated they always consume high-fat foods, whilst 49.1% said they always eat processed food high in salt. About 1.3% started smoking when they were 16–20 years old (Supplementary 1).

| Variable | Males | Females | Total (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.0004 | |||

| 18–24 | 41 | 135 | 176(77.2) | |

| 25–29 | 17 | 5 | 22(9.6) | |

| 30–35 | 22 | 8 | 30(13.2) | |

| Religion | 0.001 | |||

| Christian | 64 | 78 | 142(62.3) | |

| Islam | 8 | 49 | 57(25) | |

| Traditional | 3 | 6 | 9(3.9) | |

| Hindus | 5 | 15 | 20(8.8) | |

| Year of study | 0.02 | |||

| First year | 41 | 68 | 109(47.8) | |

| Second year | 19 | 30 | 49(21.5) | |

| Third year | 15 | 13 | 28(12.3) | |

| Fourth year | 5 | 37 | 42(18.4) | |

| Programme of study | 0.009 | |||

| Clinical dietetics | 9 | 20 | 29(12.7) | |

| Community nutrition | 4 | 14 | 18(7.9) | |

| Sonography | 14 | 43 | 57(25) | |

| Radiography | 19 | 42 | 61(26.8) | |

| Medical laboratory science | 23 | 25 | 48(21.1) | |

| Ophthalmic dispensing | 11 | 4 | 15(6.6) | |

| Residential status | 0.0006 | |||

| Resident | 34 | 138 | 172(75.4) | |

| Non-resident | 46 | 10 | 56(24.6) | |

| Total(%) | 80(35.1) | 148(64.9) |

The study result showed that the majority (87.3%) of participants practised unhealthy dietary patterns while only 12.7% practised healthy dietary patterns. More than half (54.8%) of the undergraduate allied health students were physically inactive. The study findings revealed that most students were not current smokers of tobacco (90.8%) and drinkers of alcohol (93.0%) as shown in Table 2.

| Behavioural risk factor | Frequency(n = 228) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Unhealthy diet | ||

| Yes | 199 | 87.3 |

| No | 29 | 12.7 |

| Physical inactivity | ||

| Yes | 125 | 54.8 |

| No | 103 | 45.2 |

| Current drinkers | ||

| Yes | 16 | 7 |

| No | 212 | 93 |

| Current smokers | ||

| Yes | 21 | 9.2 |

| No | 207 | 90.8 |

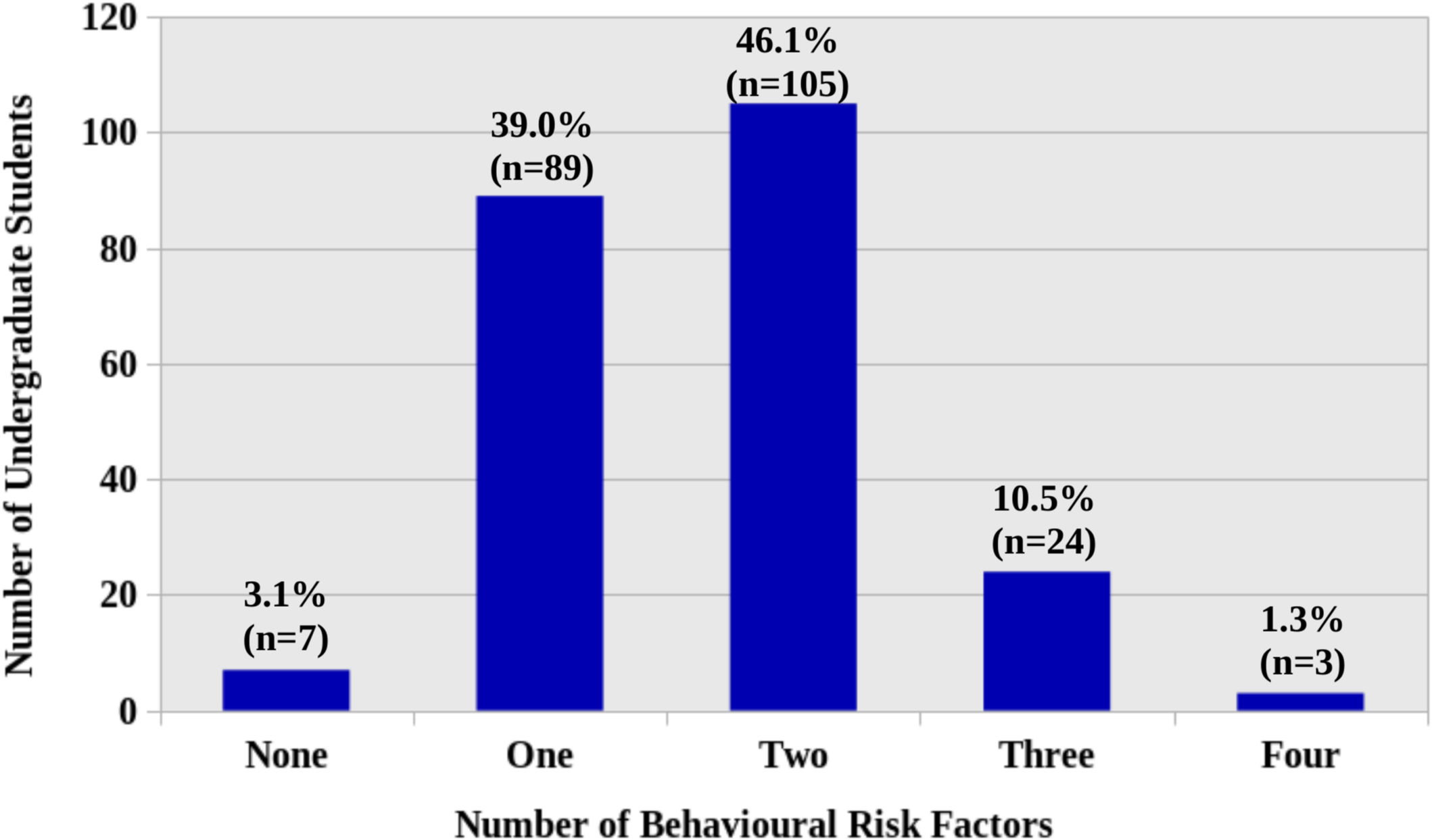

The majority (46.1%) of the undergraduate students had 2 risk factors followed by those who had 1 risk factor (39%), and 3 risk factors (10.5%). Only 3.1% of the undergraduate students had no risk factor (Figure 1).

Most undergraduate students with unhealthy dietary patterns were females (77.9%, p = 0.002), purporting that females were more likely to report unhealthy dietary practices. The proportion of female undergraduate students involved in physical inactivity was comparatively higher (55.2%, p < 0.001). The majority of participants with one and two behavioural risk factors were also females with proportions of 60.7% (p = 0.02) and 61.9% (p = 0.01) respectively. No significant associations were observed between sex and current drinkers and smokers. Details are shown in Table 3.

| Behavioural risk factors | Sex | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||

| Unhealthy diet | 44(22.1%) | 155(77.9%) | 0.002 |

| Physical inactivity | 56(44.8%) | 69(55.2%) | < 001 |

| Current drinkers | 12(75%) | 4(25%) | 0.763 |

| Current smokers | 14(66.7%) | 7(33.3) | 0.467 |

| Number of risk factors | |||

| None | 3(42.9%) | 4(57.1%) | < 0001 |

| 1 | 35(39.3%) | 54(60.7%) | 0.02 |

| 2 | 40(38.1%) | 65(61.9%) | 0.01 |

| 3 | 17(70.8%) | 7(29.2%) | 0.147 |

| 4 | 1(33.3%) | 2(66.7%) | 0.68 |

The majority of the undergraduate students with unhealthy dietary patterns were 18–24 years old (81.4%, p = 0.032), followed by those who were 30–35 years old (12.1%, p = 0.032), and 25–29 years old (6.5%, p = 0.032). The proportion of undergraduate students aged 18–24 years who were involved in physical inactivity was higher (69.5%, p = 0.010) as compared to those who were 25–29 years old (14.4%) and 30–35 years old (9.6%). The majority of participants with one and two behavioural risk factors were all 18–24 years old with proportions of (61.8%, p = 0.04) and (69.5%, p < 0.001) respectively. Most students with three behavioural risk factors were 25–29 years old (70.8%, p = 0.03). No significant associations were observed between age and current drinkers and smokers. Details are shown in Table 4.

| Behavioural risk factors | Age group (in years) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–24 | 25–29 | 30–35 | ||

| Unhealthy diet | 162(81.4%) | 13(6.5%) | 24(12.1%) | 0.032 |

| Physical inactivity | 95(76%) | 18(14.4%) | 12(9.6%) | 0.010 |

| Current drinkers | 5(31.3%) | 8(50%) | 3(18.8) | 0.910 |

| Current smokers | 9(42.9%) | 5(23.8%) | 7(33.3%) | 0.867 |

| Number of risk factors | ||||

| None | 2(28.6%) | 4(57.1%) | 1(14.3%) | 0.68 |

| 1 | 55(61.8%) | 13(14.6%) | 21(23.6%) | 0.04 |

| 2 | 73(69.5%) | 17(16.2%) | 15(14.3%) | < 001 |

| 3 | 1(4.2%) | 17(70.8%) | 6(25.0%) | 0.03 |

| 4 | 2(66.7%) | 1(33.3%) | 0(0.%) | 0.33 |

Being a nonresident student was associated with drinking of alcohol (OR = 2.5; 95%CI = 1.1–5.9). Male undergraduate students were less likely to be physically inactive (OR = 0.4; 95%CI = 0–0.9) while students reading Community Nutrition course were less likely to engage in unhealthy diets (OR = 0.7; 95%CI = 0.2–1.3) as shown in Table 5.

| Determinants | Unhealthy diet | Physical inactivity | Current drinkers | Current smokers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (ref [18-24]: years) | ||||

| 25–29 | 0.5 (0.2, 0.9) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.8) | 0.8 (0.3, 1.2) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.9) |

| 30–35 | 0.7 (0.4, 1.0) | 0.9 (0.3, 1.6) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.3) |

| Sex (ref: Female) | ||||

| Male | 1.3 (1.0, 1.6) | 0.4 (0, 0.9)† | 1.7 (0.9, 2.2) | 0.9 (0.4, 1.5) |

| Year of study (ref: first year) | ||||

| Second year | 2.3 (1.5, 5.4) | 1.6 (0.9, 2.9) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.7) | 1.2 (0.5, 2.0) |

| Third year | 1.1 (0.8, 1.7) | 0.8 (0.2, 1.5) | 2.1 (1.1, 3.3) | 1.5 (0.9, 2.2) |

| Fourth year | 2.2 (1.3, 9.4) | 1.8 (1.1, 2.6) | 2.3 (1.4, 3.9) | 1.9 (1.0, 3.2) |

| Program of study (ref: dietetics) | ||||

| Community nutrition | 0.7 (0.2, 1.3)† | 2.3 (1.4, 4.1) | 0.6 (0.3, 0.8) | 0.7 (0.3, 1.1) |

| Sonography | 0.9 (0.3, 1.7) | 1.4 (0.8, 1.9) | 2.5 (1.5, 3.5) | 1.8 (0.9, 2.6) |

| Radiography | 1.6 (1.1, 3.4) | 1.1 (0.6, 1.7) | 0.7 (0.5, 1.1) | 2.5 (1.3, 6.6) |

| Medical laboratory science | 1.3 (0.8, 2.6) | 1.6 (1.1, 2.9) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.8) | 2.1 (1.2, 3.0) |

| Ophthalmic dispensing | 2.6 (1.8, 7.4) | 0.7 (0.3, 0.9) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.4) | 1.2 (0.4, 2.3) |

| Residential status (ref: resident) | ||||

| Nonresident | 0.8 (0.3, 1.5) | 0.2 (0, 0.5) | 2.5 (1.1, 5.9)† | 0.7 (0.4, 0.9) |

- Note: Bold values indicate statistically significant at p < 0.05.

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

4 Discussion

The present study found that less than one-tenth (9.6%) of the students were within the age range of 25–29 years. This current result aligns with the study conducted by Owopetu et al. [17] who demonstrated that less than one-tenth of the students were between the age range of 25–29 years. Additionally, this study's result correlates with that of Legesse et al. [19] who found that more than one quarter (27.9%) of the participants were between the ages of 18–24 years. Females (64.9%) constituted the majority in this study. Pengpid & Peltzer and Mon et al. reported similar results. Mon et al., reported a comparatively higher proportion (72.9%) whilst Pengpid & Peltzer found a quite lower proportion of 59.2% [20, 21].

Despite the numerous health benefits of consuming fruits and vegetables as reported in literature, a greater proportion of the undergraduate allied health students (87.3%) in this study had inadequate intake of fruit and vegetables [22, 23]. Our finding is similar to what was reported by Zenu et al., and Pengpid & Peltzer who found a majority of 94.8% and 80.5%, respectively [8, 21]. The high prevalence of inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption is a major health concern as inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption is linked to increased odds of NCD, including diabetes and chronic lung disease [24]. It can also can lead to increased healthcare costs due to the treatment of chronic diseases [21]. In China, 79.9% of the labour force was at risk of inadequate fruit intake, highlighting a widespread issue across various demographics [25]. The reason for the high prevalence of inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption could be due to high prices and limited access to fresh produce as reported in literature [26]. A high proportion (80.7%) of the students consumed more than 5 g of salt in a day while 19.3% of the students in this study consumed less than 5 g of salt in a day. The current study finding on salt consumption is similar to the research conducted by Dahal et al., who found that the majority (92.7%) of the participants consumed more than 5 g of salt per day [11]. Consuming more than 5 g of salt per day can increase the risk of heart disease, including heart attacks, strokes, and cardiac arrhythmias. The economic implications of this includes lost productivity and absenteeism from work, resulting in economic losses [20].

The proportions of current smokers of tobacco (9.2%) and drinkers of alcohol (7.0%) in this present study were lower as compared to other jurisdictions [27, 28]. The reason for the lower proportion in this present study could be due to certain government initiatives. In Ghana, several control measures have been implemented. For instance, Article 66 (4) of the Public Health Act 2012, emphasizes the incorporation of tobacco education into school health programs, targeting youth to prevent early smoking initiation [29]. The Ghana Public Health Act (Act 851) provides comprehensive regulations concerning a range of public health issues, including the enforcement of tobacco control measures. These legislative frameworks encompass initiatives aimed at increasing public awareness regarding the detrimental effects of tobacco, protecting individuals from the harmful effects of second-hand smoke, facilitating tobacco cessation efforts, disseminating health warnings about the implications of tobacco consumption, and imposing restrictions on tobacco advertising and promotional activities [12, 13].

The co-occurrence of behavioural risk factors of non-communicable diseases among undergraduates is a significant public health concern. Research indicates that many young individuals exhibit multiple risk behaviours simultaneously, which can exacerbate health issues. This study's finding showed that less than one-tenth (3.1%) of the students had no behavioural risk factor for non-communicable diseases. Similarly, research done by Leatherdale found less than one-tenth (0.2%) of the participants with no risk factor for NCD [30]. Less than half (46.1%) of the students in this study had two behavioural risk factors for non-communicable diseases, which is similar to a study done by Ogbole and Fatusi which showed that one-third (39.49%) had two risk factors [31]. However, the current study finding is comparatively lower than what was found by Timalsina and Singh who reported a proportion of 78.5% with two risk factors [32]. The clustering of risk factors, such as smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity indicates that students are more likely to experience adverse health outcomes as reported in literature [33]. Therefore, there is a need for targeted interventions that address these multiple behaviours to potentially improve the health outcomes of individuals.

This present study revealed a significant association between sex and behavioural risk factors like unhealthy diet and physical inactivity. The majority of the undergraduate students engaged in unhealthy diets were females (77.9%, p = 0.002). Owopetu et al., found similar results but had a comparatively lower proportion of 55.2% [17]. More female undergraduate students were also involved in physical inactivity (55.2%, p < 001) as compared to the males in this current study. This finding corroborates the result of Owopetu et al., who found that more females (53.3%, p-value = 0.001) were involved in physical inactivity [17]. Most of the participants with multiple risk factors were females. The reason for this finding could be due to the high proportion of female participation in this study. However, on excessive alcohol consumption, this study found more males involved in excessive alcohol consumption than females. This may be due to higher alcohol tolerance and greater social acceptance of drinking among males as reported in literature [34].

We found that being a Nonresident student was associated with drinking alcohol which could be due to financial independence. Nonresident students may have more financial independence and be free from supervision, which can lead to increased spending on alcohol and other leisure activities [17]. Male undergraduate students were less likely to be physically inactive, while students reading Community Nutrition courses were less likely to engage in unhealthy diets. This corroborates the results of Changoh et al., in Cameroon [35]. This current study found a significant association between age and an unhealthy diet and physical inactivity behavioural risk factors. Unhealthy diet and physical inactivity behavioural risk factors were mostly associated with the 18–24 years age group in this study. This purports that, younger individuals are more prone to poor dietary habits and sedentary lifestyles despite the high awareness of these risk factors among young adults as reported in literature [36]. This age group (18–24 years) had more multiple behavioural risk factors as also reported by a study in Brazil [37]. It is imperative therefore to intensify the education of these behavioural risk factors for non-communicable diseases among undergraduate allied health students and students in general.

While our analysis controlled for several potential confounders, the possibility of reversed causation remains a concern. Specifically, it is possible that dependent variables may be driving the observed association with independent variables. To better understand the relationship between these variables, future research should prioritize the use of longitudinal or quasi-experimental designs that can establish temporal precedence and reduce the risk of reversed causation.

5 Conclusion

This study investigated the prevalence and correlates of behavioural risk factors for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) among allied health undergraduate students. The findings indicate that a significant proportion of students engage in unhealthy behaviours, such as physical inactivity and unhealthy diet, which increases their risk of developing NCDs. However, the consumption of tobacco and alcohol among undergraduate allied health students was generally low. The benefits of consuming healthy diets cannot be overstated. These foods are rich in essential nutrients, antioxidants, and fibre, which are crucial for maintaining good health and preventing chronic diseases. There is therefore the need to encourage students to incorporate adequate healthy diets and physical activities into their daily lives, to significantly improve their overall well-being, and reduce the risks of non-communicable diseases.

The study's results highlight the importance of promoting healthy behaviours among allied health undergraduate students, who will soon become healthcare professionals responsible for promoting healthy lifestyles among their patients. The findings also suggest that universities and health education institutions should prioritize health promotion and disease prevention strategies among their students. The correlates of behavioural risk factors identified in this study gender, programme of study, and residence status, can inform the development of targeted interventions to promote healthy behaviours among allied health undergraduate students.

6 Strengths and Limitations of the Study

The study may be limited by the number of participants included. The underlying factors that contribute to the high prevalence of unhealthy dietary practices and physical inactivity among students were not evaluated in this current study. The study was also conducted among students in one institution. Further multi-centre research is needed to explore the underlying factors that contribute to the high prevalence of these behavioural risk factors. However, the study targeted a specific population (undergraduate allied health students), which allowed for focused data collection and analysis. The study used validated and reliable data collection tools to ensure the accuracy and consistency of the data. It also involved collecting data from all available departments, to increase the validity and reliability of the findings. Appropriate statistical analysis techniques, such as descriptive statistics, inferential statistics, and regression analysis, were employed to analyze the data. The study provides practical implications for healthcare providers, policymakers, and students, which can inform the development of effective interventions and policies, highlighting the strengths of the study.

Author Contributions

Margaret Atuahene: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, validation, formal analysis, project administration, resources. Frank Quarshie: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, investigation, validation, project administration, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, visualization, formal analysis, supervision. Francis Kwaku Nyasem: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, methodology, investigation, validation, data curation, formal analysis, software, visualization. Daniel Eshun: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, methodology, investigation, validation, data curation, supervision. Philip Narteh Gorleku: methodology, conceptualization, validation, formal analysis, supervision, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Pamela Achiaa Addai: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, methodology, validation, formal analysis, supervision. Maurice Ofoe Gorleku: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, methodology, validation, formal analysis, supervision. Martin Owusu Asante: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, validation, investigation, formal analysis, software. Joseph Otchere: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, investigation, formal analysis, supervision, validation. Prince Aubin: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, methodology, validation, formal analysis, resources.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the students and management of the premier fully private college of health and allied sciences in West Africa (Klintaps University College of Health and Allied Sciences) for their support in making this study successful. This research was not funded by any external funding sources. All the authors supported this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Transparency Statement

Dr. Margaret Atuahene and Frank Quarshie affirm that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.