Association between knowledge and use of contraceptive among women of reproductive age in sub-Saharan Africa

Abstract

Background and Aims

The use of contraceptives has been considered relevant in reducing unintended pregnancies in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). However, despite evidence of knowledge of contraceptives, their use remains low in SSA. This study examined the association between knowledge of contraceptive methods and the use of contraceptives in SSA.

Methods

Data for the study were extracted from the Demographic and Health Surveys of 21 countries in SSA spanning from 2015 to 2021. A weighted sample of 200,498 sexually active women of reproductive age were included in the final analysis. We presented the results on the utilization of contraceptives using percentages with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI). We examined the association between knowledge of contraceptive methods and the use of contraceptives using multilevel binary logistic regression analysis.

Results

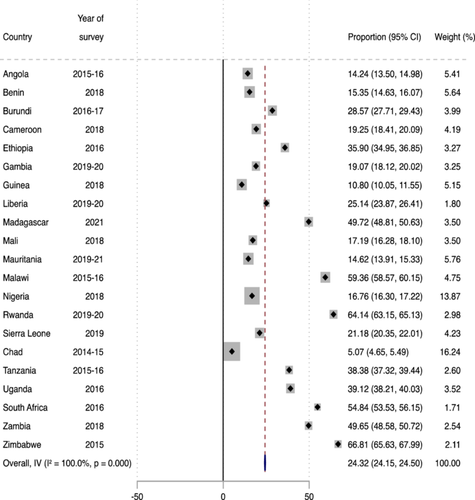

Overall, 24.32% (95% CI: 24.15–24.50) of women in SSA used contraceptives. Chad had the lowest prevalence of contraceptive use (5.07%) while Zimbabwe had the highest prevalence (66.81%). The odds of using any method of contraception were significantly higher for women with medium [Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 1.89; 95% CI = 1.80–1.98] and high [AOR = 2.22; 95% CI = 2.10–2.33] knowledge of contraceptive methods compared to those with low knowledge, after adjusting for all covariates.

Conclusion

Our study has shown that the use of contraceptives among women in SSA is low. Women's knowledge of any contraception method increases their likelihood of using contraceptives in SSA. To improve contraceptive use in SSA, targeted interventions and programmes should increase awareness creation and sensitization, which can improve women's knowledge on methods of contraception. Also, programmes implemented to address the low uptake of contraceptives should consider the factors identified in this study. In addition, specific subregional strategies could be implemented to narrow the subregional disparities.

1 BACKGROUND

Adolescent sexual and reproductive health care seeks to educate and give medical assistance to young women to aid in their understanding of their sexuality and to safeguard them against unintended pregnancy.1 Despite the sexual and reproductive health guidelines implemented by the World Health Organization (WHO) for safe sexual practices and the freedom to choose the rate of reproduction, it remains a major concern in low -and middle-income countries.2 Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has the worst reproductive health indices and has not improved in the statistics on the prevalence rate of contraception, adolescent birth rate, antenatal care coverage, and unmet need for family planning, unlike high-income countries.3, 4

Contraceptive usage is a major challenge in SSA because of cultural restrictions on sexual interaction. Given that marriage is the only premise for sexual intercourse, contraceptives use and information were solely available to members of a specific group.5, 6 However, studies indicate that knowledge of contraceptive use can translate into its practice without any barriers.3, 4 Amdist education, modernization, and mixed intercontinental practices in SSA, its influence on knowledge of contraceptive usage is still low.5 In addition, policymakers have propagated family planning services in response to the growing population and the economic downturn in SSA7

In SSA, there is low usage and minimal knowledge of modern contraceptives.8 This is because, in many African countries, postpartum abstinence is considered the sole approach to family planning. Though postpartum abstinence has waned in most African countries due to contemporary methods of contraception, it is still accepted as a more efficient way to achieve intended birth outcomes.6

Barriers such as lack of access, cultural considerations, religious objections, fear of health risks, and side effects may hinder the use of contraceptives.9 A study has shown that misconceptions about the accessibility and safety of using contraception are widespread among women in SSA.6 However, most of these barriers can be dealt with if users have a solid knowledge of the types, sources, and appropriate use of contraceptives available to them. With the growing knowledge of the types of contraceptives, most women of reproductive age in SSA only know of condoms with just a few using them.5, 10, 11 Considering the high fertility rate of women of reproductive age in SSA, the growing population, and the complexities regarding the use of contraceptives, there is a need to disseminate quality information to raise awareness for a reliable reproductive health guide.12 This will also improve the knowledge and concerns regarding unsafe abortion, teenage pregnancy, and maternal mortality rate from unintended pregnancies.13, 14

Knowledge and use of contraceptives among women is a concern for health organizations when it comes to assessing family planning as women bear almost all the responsibility for regulating fertility.7 In Nigeria, 82% of childbearing women knew at least one method of contraception, yet 82% had never used any contraceptive method.15 The probability of using any contraceptive method was high among those with knowledge of contraceptives.15 Similarly, in Ghana, although Beson et al. found high level of knowledge on contraception, this did not translate to current use of modern contraception.16 In other sub-Saharan African countries, research has consistenly showed a low prevalence of modern contraceptive use, contributing to the high incidence of unitended pregnancies, unsafe abortions, and maternal mortality.17-19

Despite the knowledge of contraceptive usage from social media, clinicians, peer groups, and pharmacy counter staff12, 20 amidst the many benefits including preserving and enhancing lives through properly planned pregnancies, SSA has not fully come to terms with this. The types of modern contraceptives and its associated drawbacks are not fully understood.21-23 Although, the United Nations has determined that one of the key indicators for measuring global progress towards achieving universal access to reproductive health should be the prevalence rate of contraception,24 this goal remains unmet in SSA. This study examined whether knowledge of contraceptives is associated with actual usage.

2 METHODS

2.1 Data source and sample

Data for this study were extracted from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) of 21 countries in SSA. We extracted the data from the women's files of the 21 countries in SSA. Only countries with recent datasets spanning from 2015 to 2021 were included in our study. The DHS is a nationally representative survey conducted in over 90 low-and middle-income countries globally.25 DHS employed a cross-sectional design in carrying out the survey. Respondents including men, women, and children were recruited using a multistage sampling technique. An expanded sampling methodology has been highlighted in the literature.26 Well-trained research assistants used structured questionnaires to collect data from the respondents on several health and demographic issues including contraceptive knowledge and use.26 A weighted sample of 200,498 women of reproductive age (15–49 years) who were sexually active were included in the final analysis (Table 1). The data used can be accessed at https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

| Country | Year of survey | Weighted sample | Weighted percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2015–2016 | 8680 | 4.3 |

|

2017–2018 | 9618 | 4.8 |

|

2016–2017 | 10,686 | 5.3 |

|

2018 | 8559 | 4.3 |

|

2016 | 9888 | 4.9 |

|

2019–2020 | 6575 | 3.3 |

|

2018 | 6509 | 3.2 |

|

2019–2020 | 4456 | 2.2 |

|

2021 | 11,482 | 5.7 |

|

2018 | 6534 | 3.3 |

|

2019–2021 | 9431 | 4.7 |

|

2015–2016 | 15,035 | 7.5 |

|

2018 | 25,394 | 12.7 |

|

2019–2020 | 8986 | 4.5 |

|

2019 | 9278 | 4.6 |

|

2014–2015 | 10,262 | 5.1 |

|

2015–2016 | 8062 | 4.0 |

|

2016 | 11,019 | 5.5 |

|

2016 | 5567 | 2.8 |

|

2018 | 8336 | 4.2 |

|

2015 | 6141 | 3.1 |

| All countries | 2015–2021 | 200,498 | 100.0 |

2.2 Variables

2.2.1 Outcome variable

The use of any method of contraception was the outcome variable in our study. To assess this variable, sexually=active women of childbearing age were asked to indicate their current use of contraceptives by method. The response options were no method, folkloric method, traditional method, and modern method. In this, we coded those who responded “no method” as not using any method of contraception. Women who reported using any of the remaining three options were said to be using a method of contraception.15

2.2.2 Key explanatory variable

The key explanatory variable in the study was knowledge of contraceptives. Women in the DHS were asked to indicate whether they have knowledge on specific methods of contraception. Those with no knowledge of any contraceptive method were categorized as “no.” Women with knowledge of any contraceptive method were coded “yes.” We adopted principal component analysis to group the number of responses. We used a standardized score, with high scores indicating high knowledge. To account for nonlinear effects, we divided the scores into tertiles: low, medium, and high.

We included 13 variables as covariates in our study. These covariates were selected due to their association contraceptive use from the literature15, 18, 27-29 as well as their availability in the DHS dataset. We grouped the covariates into individual level and contextual level variables. The individual level variables consisted of the age of the women, level of education, marital status, current working status, parity, exposure to reading newspapers or magazines, exposure to listening to radio, and exposure to watching television. Partner's educational level, wealth index, sex of household head, place of residence, and geographic subregion were the contextual level variables. The categories of the covariates can be found in Table 2.

| Use any method of contraception | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Weighted frequency | Weighted percentage | No (%) | Yes (%) | |

| Knowledge of contraceptive methods | <0.001 | ||||

| Low | 66,475 | 33.1 | 86.8 | 13.2 | |

| Medium | 64,094 | 32.0 | 65.7 | 34.3 | |

| High | 69,929 | 34.9 | 54.8 | 45.2 | |

| Women's age (years) | <0.001 | ||||

| 15–19 | 13,382 | 6.7 | 82.2 | 17.8 | |

| 20–24 | 33,694 | 16.8 | 69.9 | 30.1 | |

| 25–29 | 41,959 | 20.9 | 67.3 | 32.7 | |

| 30–34 | 37,459 | 18.7 | 64.7 | 35.3 | |

| 35–39 | 32,474 | 16.2 | 64.6 | 35.4 | |

| 40–44 | 23,338 | 11.6 | 67.9 | 32.1 | |

| 45–49 | 18,192 | 9.1 | 78.5 | 21.5 | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | ||||

| Married | 164,756 | 82.2 | 69.2 | 30.8 | |

| Cohabiting | 34,716 | 17.3 | 66.8 | 33.2 | |

| Widowed | 401 | 0.2 | 97.1 | 2.9 | |

| Divorced or separated | 625 | 0.3 | 92.3 | 7.7 | |

| Educational level | <0.001 | ||||

| No education | 74,695 | 37.3 | 84.0 | 16.0 | |

| Primary | 68,063 | 33.9 | 61.1 | 38.9 | |

| Secondary | 48,413 | 24.1 | 58.9 | 41.1 | |

| Higher | 9327 | 4.7 | 56.2 | 43.8 | |

| Current working status | <0.001 | ||||

| Not working | 68,981 | 34.4 | 72.6 | 27.4 | |

| Working | 131,517 | 65.6 | 67.0 | 33.0 | |

| Parity | <0.001 | ||||

| Nulliparity | 12,992 | 6.5 | 92.8 | 7.2 | |

| Primiparity | 29,265 | 14.6 | 69.5 | 30.5 | |

| Multiparity | 90,682 | 45.2 | 63.3 | 36.7 | |

| Grandparity | 67,559 | 33.7 | 71.5 | 28.5 | |

| Exposed to watching television | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 124,870 | 62.3 | 71.6 | 28.4 | |

| Yes | 75,628 | 37.7 | 64.3 | 35.7 | |

| Exposed to listening to radio | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 90,796 | 45.3 | 75.1 | 24.9 | |

| Yes | 109,702 | 54.7 | 63.7 | 36.3 | |

| Exposed to reading newspaper or magazine | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 168,465 | 84.0 | 71.9 | 28.1 | |

| Yes | 32,033 | 16.0 | 53.1 | 46.9 | |

| Partner's educational level | <0.001 | ||||

| No education | 64,608 | 32.2 | 84.5 | 15.5 | |

| Primary | 61,957 | 30.9 | 61.2 | 38.8 | |

| Secondary | 57,240 | 28.6 | 62.0 | 38.0 | |

| Higher | 16,693 | 8.3 | 61.1 | 38.9 | |

| Sex of household head | <0.001 | ||||

| Male | 170,126 | 84.9 | 68.3 | 31.7 | |

| Female | 30,372 | 15.1 | 71.9 | 28.1 | |

| Wealth index | <0.001 | ||||

| Poorest | 39,829 | 19.9 | 78.0 | 22.0 | |

| Poorer | 40,755 | 20.3 | 73.1 | 26.9 | |

| Middle | 39,719 | 19.8 | 69.0 | 31.0 | |

| Richer | 39,875 | 19.9 | 64.4 | 35.6 | |

| Richest | 40,320 | 20.1 | 60.0 | 40.0 | |

| Place of residence | <0.001 | ||||

| Urban | 67,105 | 33.5 | 66.3 | 33.7 | |

| Rural | 133,393 | 66.5 | 70.2 | 29.8 | |

| Geographical subregions | <0.001 | ||||

| Southern Africa | 5567 | 2.8 | 45.2 | 54.8 | |

| Central Africa | 27,501 | 13.7 | 87.6 | 12.4 | |

| Eastern Africa | 89,635 | 44.7 | 52.4 | 47.6 | |

| Western Africa | 77,795 | 38.8 | 82.9 | 17.1 | |

2.3 Statistical analyses

We used Stata version 17 to carry out the statistical analyses. We used a forest plot to present the proportion of women who use any contraceptive method (Figure 1). Next, the Pearson's χ2 test of independence was used to examine the variables with a significant relationship with contraceptive use. This was followed by a multilevel binary logistic regression analysis. Before the regression analysis, we used the variance inflation factor (VIF) to determine the extent of collinearity among the studied variables. We found the minimum, maximum, and mean VIF to be 1.01, 5.89, and 2.36, respectively. Hence, we found no evidence of high collinearity among the variables. A five-modelled multilevel logistic regression analysis was used to examine the association between knowledge of contraceptives and their use. Model O was an empty model and it showed the variance in contraceptive use attributed to the primary sampling unit (PSU). Model I included only the key explanatory variable. Model II included Model I and the individual-level covariates. Model III consisted of Model I and the contextual level variables. Model IV contained variables in Model II and the contextual level covariates. The results were presented as adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with their 95% confidence interval. We used Akaike's Information Criterion (AIC) to assess model fitness, with the last model being the best-fitted model due to its least AIC value. All the analyses were weighted. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines in writing this paper.30

2.4 Ethical consideration

Our study involved an analysis of secondary data; hence, we did not seek ethical clearance. We obtained permission to use the DHS data set from the Monitoring and Evaluation to Assess and Use Results Demographic and Health Surveys (MEASURE DHS). We complied with all ethical guidelines using secondary data for publication.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Prevalence of contraceptives use among women in sub-Saharan Africa

Overall, 24.32% (95% CI: 24.15–24.50) of women in SSA used contraceptives. Chad had the lowest prevalence (5.07%) while Zimbabwe had the highest prevalence (66.81%) as shown in Figure 1.

3.2 Distribution of contraceptive use across explanatory variables in sub-Saharan Africa

Table 2 shows the distribution of contraceptives use across the various explanatory variables. The results show that there were statistically significant differences in the use of any method of contraception accross the explanatory variables. The highest proportion of contraceptive use was reported among women with high knowledge of contraceptive methods (45.2%). Women aged 35–39 (35.3%), those cohabiting (33.2%), women with higher education (43.8%), those currently employed (33%), and multiparous women (36.7%) also had the highest proportions of contraceptive use.

Women who watched television (35.7%), listened to the radio (36.3%), and read the newspaper (46.9%) reported high utilization of any method of contraception. The highest proportions of using any method of contraception were also reported among women in male-headed households (31.7%), those in the richest wealth quintile (40.0%), and those in urban areas (33.7%). The use of any method of contraception was prevalent among women residing in the Southern region of SSA (54.9%).

3.3 Association between knowledge of contraceptives and the use of any method of contraception in sub-Saharan Africa

The odds of using any method of contraception were significantly higher for women with medium [AOR = 1.89; 95% CI = 1.80–1.98] and high [AOR = 2.22; 95% CI = 2.10–2.33] knowledge of contraceptive methods compared to those with low knowledge, after adjusting for all covariates in Model IV. Compared to adolescent girls, older women were less likely to use any method of contraception with those aged 45–49 years having the least likelihood [AOR = 0.40; 95% CI = 0.37–0.44].

Women with primary [AOR = 1.49; 95% CI = 1.43–1.55], secondary [AOR = 1.83; 95% CI = 1.74–1.93], and higher [AOR = 1.90; 95% CI = 1.73–2.09] educational levels were more likely to use any method of contraception compared to those with no education. Compared to married women, those who were widowed [AOR = 0.53; 95% CI = 0.28–0.98] were less likely to use any method of contraception. Similarly, women whose partners had primary [AOR = 1.30; 95% CI = 1.24–1.36], secondary [AOR = 1.42; 95% CI = 1.35–1.49] or higher education [AOR = 1.39; 95% CI = 1.30–1.49] were more likely to use any method of contraception compared to those whose partners had no education. Currently working women were more likely to to use any method of contraception compared to women who were not working [AOR = 1.11; 95% CI = 1.07–1.14].

The likelihood of using any method of contraception was significantly higher among primiparous [AOR = 5.69; 95% CI = 5.08–6.37], multiparous [AOR = 9.32; 95% CI = 8.33–10.43], and grandparous women [AOR = 10.87; 95% CI = 9.65–12.25] compared to nulliparous women. Also, women who were exposed to reading newspapers or magazines [AOR = 1.11; 95% CI = 1.06–1.16], those exposed to watching television [AOR = 1.14; 95% CI = 1.10–1.19], and those exposed to listening to the radio [AOR = 1.06; 95% CI = 1.02–1.10] were more likely to use any method of contraception compared to their counterparts who were not exposed. The probability of using any method of contraception was higher among women in the richest wealth index [AOR = 1.24; 95% CI = 1.16–1.32]. However, the odds of using any method of contraception were lower among women residing in rural areas [AOR = 0.92; 95% CI = 0.87–0.96], Central Africa [AOR = 0.16; 95% CI = 0.14–0.18], Eastern Africa [AOR = 0.88; 95% CI = 0.79–0.99], and Western Africa [AOR = 0.23; 95% CI = 0.79–0.99] compared to those living in urban areas and Southern Africa (Table 3).

| Variable | Model O | Model I cOR [95% CI] | Model II AOR [95% CI] | Model III AOR [95% CI] | Model IV AOR [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effect model | |||||

| Knowledge of contraceptive methods | |||||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Medium | 3.47*** [3.30, 3.64] | 2.60*** [2.48, 2.73] | 2.16*** [2.06, 2.27] | 1.89*** [1.80, 1.98] | |

| High | 5.52*** [5.24, 5.81] | 3.57*** [3.39, 3.76] | 2.73*** [2.59, 2.87] | 2.22*** [2.10, 2.33] | |

| Women's age (years) | |||||

| 15–19 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 20–24 | 1.04 [0.97, 1.12] | 0.93 [0.86, 1.00] | |||

| 25–29 | 0.99 [0.92, 1.07] | 0.86*** [0.79, 0.93] | |||

| 30–34 | 1.04 [0.96, 1.13] | 0.84*** [0.77, 0.91] | |||

| 35–39 | 1.08 [1.00, 1.17] | 0.85*** [0.78, 0.92] | |||

| 40–44 | 0.96 [0.88, 1.04] | 0.71*** [0.65, 0.78] | |||

| 45–49 | 0.56*** [0.52, 0.61] | 0.40*** [0.37, 0.44] | |||

| Educational level | |||||

| No education | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Primary | 2.47*** [2.36, 2.57] | 1.49*** [1.43, 1.55] | |||

| Secondary | 2.57*** [2.44, 2.70] | 1.83*** [1.74, 1.93] | |||

| Higher | 2.45*** [2.25, 2.67] | 1.90*** [1.73, 2.09] | |||

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Cohabiting | 0.94* [0.90, 0.99] | 0.97 [0.93, 1.02] | |||

| Widowed | 0.17*** [0.09, 0.32] | 0.53* [0.28, 0.98] | |||

| Divorced or separated | 0.35*** [0.25, 0.51] | 1.03 [0.71, 1.49] | |||

| Current working status | |||||

| Not working | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Working | 1.04* [1.01, 1.08] | 1.11*** [1.07, 1.14] | |||

| Parity | |||||

| Nulliparity | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Primiparity | 5.31*** [4.74, 5.95] | 5.69*** [5.08, 6.37] | |||

| Multiparity | 7.65*** [6.82, 8.57] | 9.32*** [8.33, 10.43] | |||

| Grandparity | 7.76*** [6.88, 8.75] | 10.87*** [9.65, 12.25] | |||

| Exposed to reading newspaper or magazine | |||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.36*** [1.30, 1.42] | 1.11*** [1.06, 1.16] | |||

| Exposed to listening to radio | |||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.16*** [1.13, 1.21] | 1.06** [1.02, 1.10] | |||

| Exposed to watching television | |||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 0.85*** [0.82, 0.89] | 1.14*** [1.10, 1.19] | |||

| Partner's educational level | |||||

| No education | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Primary | 1.51*** [1.45, 1.58] | 1.30*** [1.24, 1.36] | |||

| Secondary | 1.76*** [1.68, 1.85] | 1.42*** [1.35, 1.49] | |||

| Higher | 1.74*** [1.64, 1.85] | 1.39*** [1.30, 1.49] | |||

| Sex of household head | |||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Female | 0.79*** [0.76, 0.82] | 0.80*** [0.76, 0.83] | |||

| Wealth index | |||||

| Poorest | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Poorer | 1.19*** [1.13, 1.24] | 1.17*** [1.12, 1.23] | |||

| Middle | 1.32*** [1.26, 1.39] | 1.28*** [1.21, 1.35] | |||

| Richer | 1.39*** [1.32, 1.48] | 1.33*** [1.25, 1.41] | |||

| Richest | 1.34*** [1.26, 1.42] | 1.24*** [1.16, 1.32] | |||

| Place of residence | |||||

| Urban | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Rural | 0.88*** [0.84, 0.92] | 0.92*** [0.87, 0.96] | |||

| Geographical subregions | |||||

| Southern Africa | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Central Africa | 0.17*** [0.15, 0.19] | 0.16*** [0.14, 0.18] | |||

| Eastern Africa | 0.84*** [0.76, 0.93] | 0.88* [0.79, 0.99] | |||

| Western Africa | 0.22*** [0.20, 0.25] | 0.23*** [0.21, 0.26] | |||

| Random effect model | |||||

| PSU variance (95% CI) | 0.194 [0.165, 0.228] | 0.152 [0.128, 0.181] | 0.171 [0.142, 0.206] | 0.127 [0.107, 0.151] | 0.125 [0.106, 0.147] |

| ICC | 0.056 | 0.044 | 0.049 | 0.037 | 0.037 |

| Wald χ2 | Reference | 4155.30 (<0.001) | 6730.62 (<0.001) | 11471.28 (<0.001) | 14006.82 (<0.001) |

| Model fitness | |||||

| Log-likelihood | −203217.92 | −188932.18 | −178732.03 | −173547.56 | −166777.71 |

| AIC | 406439.8 | 377872.4 | 357510.1 | 347127.1 | 333625.4 |

| BIC | 406460.3 | 377913.2 | 357744.9 | 347290.4 | 333982.7 |

| N | 200,498 | 200,498 | 200,498 | 200,498 | 200,498 |

| Number of clusters | 1399 | 1399 | 1399 | 1399 | 1399 |

- Abbreviations: 1.00, reference category; AIC, Akaike's Information Criterion; aOR, adjusted odds ratios; BIC, Bayesian Information Criterion; CI, confidence interval; ICC, intraclass correlation; PSU, primary sampling unit.

- * p < 0.05

- ** p < 0.01

- *** p < 0.001.

4 DISCUSSION

Using the most recent DHS data of 21 sub-Saharan African countries, the present study examines the association between contraceptive knowledge and the actual use of any method of contraception. Overall, only 24.32% of sexually-active women aged 15–49 used any method of contraception in SSA. The proportion observed in this study mirrors that of a study conducted in South Nigeria15 that found only 18.3% use any method of contraception. However, the observation is lower when compared to high-income countries like the United States where there is a 61.4% use of any method of contraception.31 While the proportion of using any method of contraception was low across SSA, Zimbabwe reported the highest usage (66.81%) while Chad reported the least usage (5.07%). The reasons accounting for the varied proportions in contraceptive use may be due to the differences in contraceptive accessibility and a reflection of how sociocultural belief systems in the respective countries affect women's use of any method of contraception.

The findings from this study support the hypothesis that there is a strong positive association between contraceptive knowledge and the actual use of any method of contraception among women of reproductive age in SSA. That is, the higher the knowledge level of a woman, the more likely she is to use any method of contraception. This is similar to what has been reported in Ukoji et al.15 and Yaya et al.'s32 study where high contraceptive knowledge was significantly associated with higher odds of actual use of any method of contraception. One possible explanation for the observed association could be an increase in the perceived self-efficacy to use contraception. For instance, Tomaszewski et al.33 have shown that contraceptive use tends to be high when there is high contraceptive self-efficacy arising from a high contraceptive knowledge. Furthermore, being knowledgeable about contraceptives can enlighten women about the benefits of using contraceptives, hence, facilitating and informing healthcare decision-making. Also, we posit that high contraceptive knowledge can improve women's sexual empowerment to have communications with their partners regarding contraceptive use.

An inverse association was established between age and contraceptive use. This finding is corroborated by Yaya et al.'s32 study that found lower odds of contraceptive use among women aged 35–49 compared to adolescent girls. It is possible that older women might have a higher desire to have children, and therefore, would be less motivated to use any method of contraceptives. From a cultural perspective, most countries within the sub-Saharan African region frown on pregnancy out of wedlock and pregnancy when one is an adolescent.34 Adolescents who get pregnant are often stigmatized and ostracized by society.35 Hence, contraceptive use provides an avenue for adolescents to escape shame and reproach from society, and still be able to fulfill their sexual desires.36 Another perspective to this could be that younger women are more likely to be sexually active and may therefore be at a higher risk of experiencing unintended pregnancies. Hence, informing the high use of contraceptives among this cohort.

Higher educational attainment of the woman and her partner was associated with a higher likelihood of using any method of contraception. Similar findings have been reported in Nigeria15 and Kenya.37 Higher educational attainment enables both the woman and her partner to have greater access to health information including information on contraceptives. The information received helps to dispel myths and misperceptions surrounding contraceptive use, thereby informing their decision to use it. Relatedly, we found that exposure to the media was associated with higher odds of using any method of contraception—a result that is consistent with what has been reported in Uganda38 and India.39 Thus, highlighting the opportunities that the mass media provide to promote contraceptive use among women of reproductive age in SSA.

Women who were currently working and those in the richest wealth index were more likely to use any method of contraception compared to those who were not working and those in the poorest wealth index. These results were expected because, besides the traditional methods of contraception, all other types of contraceptives must be purchased. However, in many sub-Saharan African countries, the cost of contraceptives is not covered by health insurance. This means that individuals from poorer households and those who are not working might not be able to afford contraceptives, thereby reducing their likelihood of using them. On the other hand, women from affluent households and those working have the financial resources to access any method of contraception. The result is corroborated by previous studies conducted in SSA32 and Uganda.38

Compared to nulliparous women, those who had one or more children were more likely to use contraceptives. The result aligns with the findings of a multicountry study of 73 low-and middle-income countries40 that found lower contraceptive use among nulliparous women compared to other parities. Nulliparous women may have a high desire to bear children. Therefore, they may tend to avoid contraceptive use to increase their chances of getting pregnant. It is also possible that women with one or more children may have completed their desired family size. For that matter, they may want to use a contraceptive method to prevent unplanned pregnancies.

Rural-dwelling women were less likely to use any method of contraception compared to those in the urban areas. This agrees with a study conducted in India39 that found urban-dwelling women to be more likely to use any method of contraception. The result may be explained by the point that rural areas often lack access to healthcare and family planning services,40 limiting contraception options. Another plausible explanation could be that women in rural areas may be more inclined to adhere to traditional and conservative perceptions about contraceptives which tends to be a barrier to their actual use of any method of contraception. Finally, the study found significant differences across the geographical subregions, with women in the Central, Eastern, and Western regions reporting the least likelihood to use any method of contraception. This picture may reflect the lapses in the current family planning regimes across the various sub-regions.

4.1 Implications for policy and practice

Our study has some implications for policy and practice. The findings underscore the need to improve contraceptive knowledge among women of reproductive age in SSA to enhance contraceptive use. Practically, this could be achieved by leveraging the mass media to reach women with the education and information necessary to improve their contraceptive knowledge. Also, the findings suggest that there is a need to consider including contraceptives in the health insurance policies of sub-Saharan African countries to help women from poorer wealth status to gain access to contraceptives. Community-based health services programmes can be implemented in all rural areas in SSA to enhance accessibility to healthcare services and commodities, including contraceptives.

4.2 Strength and limitations

This study used the most recent DHS data set. Hence, the findings are likely to be reflective of the current status quo. However, there were some limitations. For instance, the DHS uses a cross-sectional design; therefore, it is impossible to establish causal inferences between contraceptive knowledge and the actual use of any method of contraception. Also, due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, there is the possibility of recall bias and social desirability bias. Essential cultural factors were lacking in the data used. Thus, limiting the extent to which we were able to interpret our findings.

5 CONCLUSION

Our study has shown that the use of contraceptives among women in SSA is low. Women's knowledge of any contraception method increases their likelihood of using contraceptives in SSA. Enhancing contraceptive use in SSA requires targeted interventions to specifically reach women with lower wealth status, those residing in rural areas, nulliparous women, and older women of reproductive age. Furthermore, implementing tailored subregional strategies is essential to address and reduce existing disparities within the subregions. Recommendations for improvement include developing initiatives that focus on education and awareness campaigns in underserved communities, increasing accessibility to contraceptive resources in rural areas, and designing programs that cater to the unique needs of nulliparous and older women.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Irene Esi Donkoh: Formal analysis; methodology; writing—original draft. Joshua Okyere: Formal analysis; methodology; writing—original draft; writing—review & editing. Abdul-Aziz Seidu: Formal analysis; investigation; writing—review & editing. Bright Opoku Ahinkorah: Methodology; supervision; writing—review & editing. Richard Gyan Aboagye: Formal analysis; methodology; writing—original draft. Sanni Yaya: Conceptualization; investigation; supervision; writing—review & editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the MEASURE DHS project for their support and for free access to the original data.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

TRANSPARENCY STATEMENT

The lead author Sanni Yaya affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data used in this study were obtained from the DHS Program and available at: https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.