In their own words: An exploration of primary children's participation in a dementia education program

Abstract

Issue Addressed

As the population ages the prevalence of dementia increases and children are increasingly experiencing family members and older friends living with dementia. Unfortunately, stigma about living with dementia is common. Increasing understanding about dementia among children has the potential to reduce this stigma. This paper reports on the qualitative findings of Project DARE (dementia knowledge, art, research and education), a school-based, multi-modal, arts program designed to increase understanding about dementia among children aged 8–10 years.

Methods

A constructivist grounded theory approach was used to understand students' experience of the intervention. Thematic analysis was used to identify key themes emerging from interviews with randomly selected students (n = 40) who had taken part in the program.

Results

The data analysis generated three themes related to students' awareness of dementia and experiences of the program: (1) nurturing empathy, (2) memory loss is complex, (3) learning about dementia through the arts to promote resilience. These themes show that the intervention increased students' awareness of dementia, and empathy towards people who are both directly and indirectly affected by dementia.

Conclusions

Although dementia education can be viewed as too sensitive for primary aged students, the current study demonstrates that such initiatives are feasible and can be effectively implemented with this age group.

So What?

Changing student's beliefs about dementia can positively impact their relationships with people living with dementia.

1 INTRODUCTION

In Australia it is estimated that 472 000 people currently live with some form of dementia, with these figures predicted to rise to over 1.1 million by 2058.1 As the number of people diagnosed with dementia increases, so too does the likelihood that children and young people will meet, live with, or even care for someone with a form of dementia.2

Research indicates that increasing children's familiarity with mental illness and health disorders is an important factor in destigmatising perceptions and increasing empathetic interactions.3-5 While the literature reports on the impact of dementia education programs in secondary schools,3, 6, 7 few studies have examined such interventions with primary school students.

This paper reports on the findings from interviews with the students who took part in Project DARE (dementia knowledge, art, research and education). Project DARE was a multi-method study evaluating the effects of an education intervention to promote understanding about dementia among Stage 2 primary school children. The intervention was a short educational program that was developed to improve primary school students' understanding of dementia through the use of visual arts. The development of the DARE intervention has previously been described in detail elsewhere.8, 9 The aim of the student interviews was to understand their experiences in undertaking the education intervention.

2 METHODS

Both the quantitative data collected from a pre-post survey and analysis of the students' artworks showed that participation in Project Dare increased students' understanding and knowledge of dementia.8, 9

2.1 Study setting

Project DARE was delivered at a school in New South Wales, Australia, during three lessons, over a three-week period, to all Year 3 and Year 4 students (Stage 2, aged 8–10 years). In Lesson 1, the students created an artwork about memory, in Lesson 2 they learned about dementia and in their final lesson they adapted their artwork to represent their developing understanding of dementia.8, 9 During the art lessons, artists demonstrated the use of techniques to express emotions and experiences.

2.2 Sample

A random sample of 40 students—10 from each class—were interviewed. In total 131 students were consented to participate in the intervention.

2.3 Intervention

Interviews were conducted by one of the authors (Corinne A. Green) and videotaped after Lesson 3. Corinne A. Green was on site for all three lessons, interacting with students as they completed the lesson activities, but did not directly teach any portion of the lessons. On average, the interviews lasted just over 4 minutes. The questions are described in Table 1.

| The students' original artwork from Lesson 1 |

|

|

|

| The student's adapted artwork from Lesson 3 |

|

|

|

| The experience as a whole |

|

Each interview was double transcribed verbatim, first using the automated software Descript©, and then manually, to correct and verify the accuracy of each transcript. All data were anonymised, by use of a numerical code.

2.4 Design

A constructivist grounded theory approach was taken as the researchers wanted to gain a deeper understanding of the students' experience of Project DARE.10 This methodology was appropriate as it sees knowledge as socially constructed with multiple viewpoints. Further, the methodology gave the students a voice, as it allowed them to express their experience and reflect on what they learnt through the process.

In a deviation from the standard grounded theory methodology,10 data collection and data analysis did not occur iteratively. This was due to the intervention being run in a school, which meant that all students received the same lesson on the same day.

2.5 Data analysis

The coding of interview data were an iterative process.11 Interview transcripts were separated into two sections, the first being the students' discussion of their original artwork, and the second being a discussion of their second artwork and their beliefs about the program. This allowed the researchers to consider data elements from the students' viewpoint. This approach to the coding allowed the researchers to reflect on the ideas in the data and develop a general sense of meaning, tone, depth and credibility of the information.12

Initially open coding was used. Each section was coded inductively using a Microsoft Excel™ spreadsheet. Relevant codes were applied as headings in each column, and applicable student statements were tagged accordingly. Open coding of the interview data were used to create categories based on themes. As the interviews were read and re-read, consideration of the context, tone and connection to the artwork produced by the students, themes began to be generated. This resulted in the creation of a coding matrix which was refined once all interviews had been coded, and then reapplied to all transcripts. The development of such a matrix ensured consistency, transparency and confirmability in the coding process.13 Indexes of student statements in each coding category were compiled to enable thematic refinement. Viewing the data in such a manner allowed for easier identification of similarities among a large number of transcripts and enabled the extraction of more credible conclusions.13

Keeping the students' drawings in mind, the process maintained the inherent link between the drawings and the interviews through the students' perspective, rather than imposing a perspective and/or expectation of the researcher on the data.

In relation to specific coding processes, each student was assigned a relevant code only once. This decision was made because of variations in the sophistication of oral language skills among the children in this study,14 and hence repetition of information could not be consistently used to reinforce thematic importance. Methodological reliability was ensured through the random selection and coding of 10% (n = 4) of interviews by two of the authors. Discrepancies between coders' themes were discussed, and any necessary amendments applied to all interviews to ensure consistency.15

Word clouds composed of phrases from the students statements were also generated using Wordle (https://wordart.com) (Figure 5). A maximum of two phrases per student were included, with phrase selection based on relevance and accuracy as related to students' holistic artwork descriptions.

2.6 Ethical approvals

Ethics approval was obtained from both the local Health Research Ethics Committee (2016/974) and the NSW Department of Education State Education Research Applications Process (SERAP 2016522). Parents and carers received participant information sheets and consent forms prior to the project initiation.

2.7 Findings

Thematic analysis of each phase generated three themes: (1) nurturing empathy, (2) memory loss is complex, (3) learning about dementia through the arts to promote resilience.

2.8 Theme 1: Nurturing empathy

Comments in this theme related to students' beliefs about the impact of dementia. All the students made negative associations with dementia, using words such as ‘frustrating’, ‘sad’ and ‘shocking’ to describe its impact. These comments were further categorised into two distinct sub-themes: (1) Knowing someone with dementia would be challenging, and (2) Having dementia would be frustrating.

2.8.1 Knowing someone with dementia would be challenging

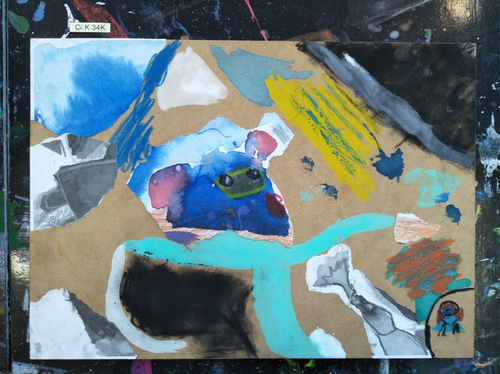

It made me a bit sad. Just that kids have to live with someone or know someone in their family that doesn't understand… like they could come up to cuddle them and, “Oh, I'm so happy to see you”, but then, “Who are you?”, so it could be quite heartbreaking […] that they don't know who you are and you don't feel like you're loved by your grandparents or parents or whoever it is that you're related to. Yeah, so that was sad. (WGH34K)

2.8.2 Having dementia would be frustrating

Students felt that having dementia would be frustrating. Many of these comments expressed how dementia could lead to feelings of isolation, as well as frustration at being unable to remember missing and incorrect parts of memories (Figures 1 and 2). Words used to describe these ideas included ‘anxious’ and ‘angry’.

2.9 Theme 2: Memory loss is complex

Comments related to students' understanding of how memories are affected by dementia, were categorised into three sub-themes: (1) Memories slowly fade, (2) Memories disappear completely and (3) Memories become jumbled. Students demonstrated an understanding of the complexity of memory loss among people with dementia, both describing and visually depicting memory loss either in terms of a slow process over time, a complete loss of memory or a jumbling of memories. This demonstrated an understanding of the variability in how memory loss can affect people with dementia.

2.9.1 Memories slowly fade

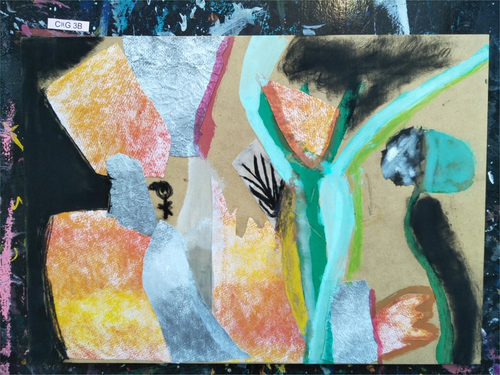

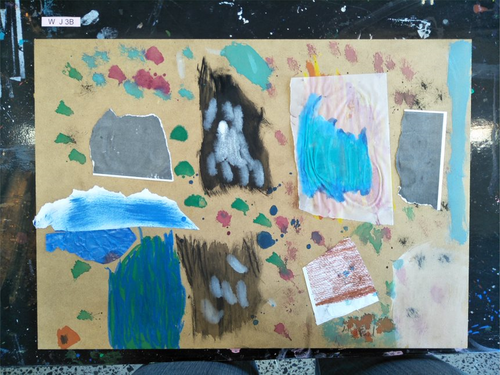

Students expressed the belief that the memories of people with dementia fade slowly and/or are replaced by new memories (Figure 3). Many students described the process of memory loss as “crumbling”, ‘fading’, or ‘cracking’. Students who shared this belief often mentioned using visual art techniques such as darkening, creasing, or otherwise obstructing sections of their artwork to express this idea, as demonstrated in the quotes below.

2.9.2 Memories disappear completely

Students expressed the belief that people with dementia lose their memories completely. Descriptions of this process were often very visual, with students making connections between memory loss and blackness or death. Students who held this perception often used methods such as excluding elements of their original artwork from their second piece of art, or using darker colours in their second artwork.

2.9.3 Memories become jumbled

Students described the process of memory loss as a more complex interaction between old memories. Many students expressed this belief by comparing memory loss to losing pieces in a puzzle, having elements of varying memories appearing randomly, or recalling memories with incorrect details. Students often described how they presented these ideas through the inclusion of elements which were not present in the first artwork, as well as through the use of non-traditional or inverted colours (Figure 4).

The person has forgotten and is really trying to remember, but they’re just trying to put the pieces together. (PAV34K)

2.10 Theme 3: Learning about dementia through the arts to promote resilience

This theme captured the students' views on participating in Project DARE. It was clear that this art-based education intervention promoted resilience among the students who participated. The majority of these comments revealed two sub-themes: (1) The project helped students develop empathy and positive coping strategies, and (2) The art-based learning experiences provided a positive outlet for students.

2.10.1 The project helped students develop resilience and positive coping strategies

I thought it was really fun… Doing, like, learning about people with dementia and how you can help them. (CB3B)

Learning more is like what I want to know… and you get used to it just in case…like maybe your family member gets dementia and then you can go ‘Okay. I know what's going to happen’. I shouldn’t get mad at them because it's not their fault, it's…they’re just getting this dementia. (KPEP45C)

You kind of get that feeling in your brain that, um, how people would feel, um with dementia. (TMC34S)

I could remind her, her name. I would remind her, her family and I'd remind her that it's… it's not that bad when you have love. (CRK34K)

2.10.2 The arts-based learning experience was a positive outlet of feelings for students

I think it was really fun… I liked that we got to do art because in most of the things we do at school there isn't really much art in it. (JEG45C)

I thought it was really fun. I wish we could do it again…you got to put your feelings and everything on the page so you could express and not keep holding it in until you’re, like, who knows, seventy-six!. (SL45C)

It was fun… The artwork, and, like, getting to see other people's artwork and how they felt in all those memories. (RPG34S)

At the start I didn't really know what dementia was, […] so after this, I felt like very sad for the people that have, like, people in the family that have dementia and they forget their… and it just feels very sad. (TKU34S)

2.11 Use of art techniques to express understanding of dementia

Comparing students' ideas about the artworks they created before and after the dementia information lesson also revealed students' increased understanding of the impact of dementia (Figure 1). While discussing their initial artworks, most students stated that they had drawn upon an experience or dream that had happy or positive connotations. The artistic techniques mentioned while describing these artworks involved using colour to portray meaning, adding or removing finer details and miscellaneous additions such as text.

By comparison, when discussing the artworks created after the dementia lesson the majority of comments described some form of darkness or confusion. The artistic techniques discussed involved manipulating colours, obscuring parts of the artwork, altering the texture of the artwork, creating sections within the artwork and adding or removing elements (Table 2 and Figure 5).

| Student | Decisions made in the original artwork | Decisions made in the second artwork |

|---|---|---|

| JMCS34K | I put light colours everywhere… The bright colours showed that I was happy when I was there. And really… and I was enjoying it. | This is an artwork where everything's mixed up and so there's different memories, like that when I went to Heron Island and then… the sun is, um, down in the corner and the sky is up… [About a crab added to the art] Yeah, that's from a different memory. |

| KEG34K | I try and show it like a bright, happy yellow, because those characters are especially, like, cheery. | This part of the artwork, upside down, greyed, painted with red ink, and then this papery stuff on top of it. |

| SL45C | When I was about two or 3 years old I went to Hamilton Island and… we were sitting on the brick wall there where there's all trees, and, um, we were watching the sunset and I saw, like, dolphins go past and, um, it was really amazing sight… | I sort of, like, ripped out the same bits of paper and put one bit grey and a bit of it blue and colour, cause it's like that… a bit of that scene's forgotten. |

3 DISCUSSION

It was important to understand how and why the intervention had a positive impact on the students' knowledge of and attitude towards dementia. Adopting a constructivist grounded theory analysis guided how the authors undertook the data analysis. The authors used the data to gain an in-depth understanding of the impact of creating the artwork on the students. Analysis of interview data from 40 students revealed that Project DARE, a visual arts-based dementia education intervention, had positively impacted students. The three themes: ‘Nurturing empathy’, ‘Memory loss is complex’, and ‘Learning About Dementia Through the Arts to Promote Resilience’ highlighted that the intervention increased students' perceptions, awareness, and empathy towards people both directly and indirectly affected by dementia. The positive engagement and conceptual growth revealed by the current study may signal a need for further investigations into primary-aged dementia education programs, particularly as many current programs focus on dementia education in secondary schools.3, 6, 7 Other primary school-based dementia education programs have reported similar findings despite the intervention varying for example, Kids4Dementia online modules4; online modules with and without an intergenerational program5; and the use of hip-hop.2 Given these positive outcomes, further research into the students' retention of knowledge and personal attitudes may be useful. This finding suggests that children's beliefs are more flexible than adults',16 and that addressing stigmatised perceptions towards conditions such as dementia may help in their early identification and treatment.2, 17

Students' appreciation for a learning experience which while aligned to the curriculum was different from their typical school tasks was notable. The literature indicates that arts-based learning experiences can result in positive outcomes in engagement, academic achievement, and students' personal development.18-20 However, many classroom activities continue to focus on more traditional literacy-based tasks.21 Students expressed enjoyment in using visual arts to explore and consolidate their understanding about dementia. The community artists provided the students with the artistic tools and techniques to show their learnings about dementia. The students placed importance on the opportunity to be creative, have a greater sense of freedom and autonomy during the art-creation process, and used art as a productive outlet through which they could both explore and demonstrate their growing understanding of dementia. Similar findings have been reported by Pavlou,19 when exploring topics ranging from the transition to high-school to human rights. Given these findings, educational practitioners may need to more actively explore practical pedagogical approaches which facilitate integrated learning across the school curriculum. The need for adequate professional development or alternative programming approaches to support this endeavour may be another area for further consideration.

The findings from this research need to be considered in light of a number of methodological limitations. Primarily, due to the intervention being school based, the researchers only had access to the students on certain days. Each stage of the intervention was delivered to all students on the same day. This prevented the concurrent collection and analysis of data that is traditional with a grounded theory approach. Instead, a random sample of students were interviewed, and the data were subsequently analysed. However, as this was the first time that the project had been delivered the insights generated from the student interviews, are invaluable in informing further iterations of the program.

4 CONCLUSION

This study demonstrated that it is both plausible and effective to implement a dementia education initiative with younger students. Students in this study indicated that learning about dementia was enjoyable and that they would engage with the experience again. The use of an art-based education intervention was found to promote resilience among school-aged children. Students described a sense of pride about their new knowledge and felt better-equipped and more confident to act within their community. This is of importance as the community will be increasingly composed of older citizens and people living with dementia. Changing students' beliefs about dementia may positively impact their relationships with people living with a dementia both in their families and communities and may even encourage them to work within aged care in the future. Such changes in attitude are key to creating dementia-friendly communities. The authors recommend replicating this study both with dementia education and with other health care topics that are stigmatised, such as ageing and mental health.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to express our gratitude to the staff and students of Thirroul Public School. We would also like to thank the community artists that made this project a reality: Jennine Primmer, Penny Harris, Nina Young, Laura Stekovic & Angela Forest. The authors acknowledge that Country for Aboriginal peoples is an interconnected set of ancient and sophisticated relationships. The University of Wollongong spreads across many interrelated Aboriginal Countries that are bound by this sacred landscape, and intimate relationship with that landscape since creation. We acknowledge the custodianship of the Aboriginal peoples of this place and space that has kept alive the relationships between all living things. The authors acknowledge the devastating impact of colonisation on our campuses' footprint and commit ourselves to truth-telling, healing and education. Open access publishing facilitated by University of Wollongong, as part of the Wiley - University of Wollongong agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The original Project DARE intervention was funded by a UOW Global Challenges seed grant. Subsequent work has been funded by a UOW Health Impacts Research Centre grant.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.