Commercially available foods for young children (<36 months) in Australia: An assessment of how they compare to a proposed nutrient profile model

Abstract

Issue addressed

To assess the nutritional composition of commercially available foods (CAFs) for infants and toddlers sold in Australia to determine whether they meet World Health Organization (WHO) Europe's proposed standards for nutritionally appropriate foods for children <36 months.

Methods

A cross-sectional retail audit of infant (n = 177) and toddler (n = 73) foods found in-store and online at three major Victorian supermarkets was conducted in August/September 2019. Products were grouped according to WHO Europe's food categories and their nutrient content assessed against specific composition standards applicable to their category. The presence of added sugar in each product was also recorded.

Results

Most infant products (71%) were soft-wet spoon-able, ready-to-eat foods whereas the most prevalent category for toddler products was dry finger foods and snacks (71%). Overall, just one-third of CAFs met all the nutrient recommendations for their category, with infant foods more likely to be compliant than toddler foods (43% vs. 10%; P < .001). Around 9 in 10 infant (93%) and toddler (89%) CAFs contained added sugar according to the Public Health England definition of ‘free’ sugars.

Conclusions

There is considerable scope to improve the nutritional composition of Australian CAFs for both infants and toddlers, to reduce harmful sugars in these foods and to improve the energy density of them. For CAFs marketed as suitable for toddlers there is also considerable scope to reduce the sodium content.

So what?

These findings support the need for stronger regulation of CAFs for infants and toddlers to better promote healthy eating patterns and taste preferences in young children.

1 INTRODUCTION

Infant feeding guidelines in Australia recommend that infants are exclusively breastfed until around 6 months of age when complementary foods are to be introduced to meet an infant's increasing nutritional and developmental needs.1 From 12 months of age and beyond, children should be transitioning to eating family foods, consistent with the Australian Dietary Guidelines.2 It is recommended that consumption of foods with high levels of saturated fat, added sugars, and/or added salt should be avoided completely for infants (ie those aged under 12 months)1 and restricted in toddler diets (ie those aged 12-<36 months).2 Despite recommendations, evidence suggests that nutrient-poor foods of this nature are being marketed as suitable for both infants and toddlers.3, 4

There has been constant growth in the market for commercial infant and toddler foods in Australia over the past decade, suggesting increased consumption by young children, and this is forecast to continue over the coming 5 years.5, 6 However, there are concerns that the availability of some of these commercial foods are undermining work to promote optimal complementary feeding practices.7 Furthermore, as the first 36 months in a child's life is an important period for establishing healthy eating patterns and taste preferences, regular consumption of these products may lead to longer term unhealthy dietary patterns and increase a child's risk of unhealthy weight gain.8-10 Although there is some regulation of commercially available foods (CAFs) for infants in Australia (eg limits on sodium content), those aimed at toddlers are currently not subject to any specific regulations.11

Globally, the World Health Organization (WHO) and its offices have released and approved various guidelines and manuals to assist all member states to end the inappropriate promotion of CAFs for infants and toddlers. In 2019, WHO Europe published their discussion paper outlining a draft nutrient profile model (NPM) to drive change in the composition, labelling and promotion of these foods.12 The proposed NPM was developed following an extensive literature review and validated against label information from over 1300 products on the market in the United Kingdom, Spain and Denmark and has subsequently been successfully applied to foods for infants and toddlers in seven additional European countries.13

The primary aim of the current study was to assess the nutritional composition of CAFs for infants and toddlers available in Australia to determine whether they meet the proposed standards put forward by WHO Europe. Infant and toddler foods were looked at separately given the differing status of regulation of CAFs for these two age groups in Australia. The Australian and New Zealand food regulator is currently considering added sugar labelling on all packaged foods, which would include CAFs for infants and toddlers.14 Furthermore, the Food Regulation Standing Committee are also exploring potential regulatory options to improve infant and toddler CAFs, while the Healthy Food Partnership have established a reference group to develop guidance for industry.15 In light of this policy context, a secondary aim of the current study was to identify the proportion of CAF products for infants and toddlers that contain added sugar/s and their most common sources of added sugar, given there are currently no regulations on how much added sugar these foods can contain.

2 METHODS

The sampling frame for this study was all foods for infants and toddlers found in-store in the Melbourne suburb of Prahran, and online at three major Victorian supermarkets (Coles, Woolworths and Aldi) in August and September 2019. As supermarkets do not distinguish between infant and toddler products, all CAF products included in this study were found primarily in the ‘baby’ aisle (in-store) or under the ‘baby’ tab (online). A small number of products specifically labelled for the toddler age group were also found in the freezer section or under the ‘freezer’ tab online. Yoghurts located in the fridge section or under the ‘dairy, eggs and fridge’ tab online were excluded from this study. Coles, Woolworths and Aldi were selected as together they represent the majority (76%) of the supermarket and grocery store market share in Australia.16 Products were eligible for inclusion if they were labelled as suitable for children <36 months. Nutrition data for each product were extracted from photographs (in-store data collection) or screenshots (online data collection) of the front- and back-of-pack and manually recorded in an excel spreadsheet. Data included product name, brand, age on pack, serve size, ingredients and nutrient composition (eg sugar, sodium, fat, protein) per serve and 100 g. Of the 280 unique products identified, 30 were available online-only and nutrition or packaging information was unable to be sourced on the supermarket or company websites. These 30 products were therefore excluded, with the final sample for analysis comprising 250 products from 21 brands.

Products labelled as suitable for children under 12 months (ie age on pack was either 4+, 5+, 6+, 7+, 8+ or 10+ months) were categorised as infant foods while those labelled as suitable for children aged 12 to <36 months (ie age on pack was either 12+ months, 1+ years, 1–3 years, 1–4 years or 1–5 years) were categorised as toddler foods. Using WHO Europe's proposed food categories,12 each product was coded into one of five broad categories: (1) dry, powdered and instant cereal/starchy food; (2) soft-wet spoon-able/ready-to-eat foods; (3) meals with chunky pieces; (4) dry finger foods; and (5) snacks and juices and drinks. Within each broad category, products were further broken down into sub-categories (see Table 1). Each product was then assessed against the specific nutrient composition standards applicable to their sub-category (see footnotes to Table 2), with the exception of trans fatty acids as these are not labelled in Australia. The ingredients list was used to evaluate the addition of sugars and/or sweeteners as per WHO Europe's NPM definition which includes: (i) all monosaccharides and disaccharides; (ii) all syrups, nectars and honey; (iii) fruit juices or concentrated/powdered fruit juice, excluding lemon or lime juice; (iv) nonsugar sweeteners. The proportion of dried or pureed fruit and protein source (for meals) were also evaluated using the ingredients list, while the nutrition information panel was used to evaluate energy density and thresholds for other nutrients. Where a criterion quantified a maximum or minimum kilocalorie (kcal) amount of a particular nutrient per 100 g, this was calculated as follows: ([nutrient per 100 g/energy per 100 g] * 100) * 4.18.

| WHO Europe proposed food category | Infant productsa | Toddler productsb | Total products | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| 1 | Dry, powdered and infant cereal/starchy food | 12 | (6.8) | 0 | (0.0) | 12 | (4.8) |

| 1.1 | Dry or instant cereals/starch | 12 | (6.8) | 0 | (0.0) | 12 | (4.8) |

| 2 | Soft-wet spoon-able, ready-to-eat foods | 125 | (70.6) | 7 | (9.6) | 132 | (52.8) |

| 2.1 | Dairy-based desserts and cereal products | 15 | (8.5) | 2 | (2.7) | 17 | (6.8) |

| 2.2 | Fruit puree with or without addition of vegetables, cereals or milk | 78 | (44.1) | 5 | (6.8) | 83 | (33.2) |

| 2.3 | Vegetable only puree | 6 | (3.4) | 0 | (0.0) | 6 | (2.4) |

| 2.4 | Pureed vegetables and cereals | 2 | (1.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (0.8) |

| 2.5 | Pureed meal with cheese (but not meat or fish) mentioned in the name | 3 | (1.7) | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (1.2) |

| 2.6 | Pureed meal with meat or fish mentioned as first food in product name | 15 | (8.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 15 | (6.0) |

| 2.7 | Pureed meals with meat or fish (but not named as the first food in product name) | 6 | (3.4) | 0 | (0.0) | 6 | (2.4) |

| 2.8 | Purees with only meat, fish or cheese in the name | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| 3 | Meals with chunky pieces | 17 | (9.6) | 14 | (19.2) | 31 | (12.4) |

| 3.1 | Meat, fish or cheese-based meal with chunky pieces | 12 | (6.8) | 11 | (15.1) | 23 | (9.2) |

| 3.2 | Vegetable-based meal with chunky pieces | 5 | (2.8) | 3 | (4.1) | 8 | (3.2) |

| 4 | Dry finger foods and snacks | 23 | (13.0) | 52 | (71.2) | 75 | (30.0) |

| 4.1 | Confectionery, sweet spreads and fruit chews | 1 | (0.6) | 9 | (12.3) | 10 | (4.0) |

| 4.2 | Fruit (fresh or dry whole fruit or pieces) | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (4.1) | 3 | (1.2) |

| 4.3 | Other snacks and finger foods | 22 | (12.4) | 40 | (54.8) | 62 | (24.8) |

| 5 | Juices and other drinks | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| 5.1 | Single or mixed fruit juices, vegetable juices, or other nonformula drinks | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| 5.2 | Cow's milk and milk alternatives with added sugar or sweetening agent | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Total | 177 | (100.0) | 73 | (100.0) | 250 | (100.0) | |

- a Infant products were those labelled as either 4+ months, 5+ months, 6+ months, 7+ months, 8+ months or 10+ months.

- b Toddler products were those labelled as either 12+ months, 1+ years, 1–3 years, 1–4 years or 1–5 years.

| WHO Europe proposed food category | Meets all proposed nutrient composition standards (%) | Dried or pureed fruit within proposed limitb (%) | No added sugars/sweetenersc (%) | Finger food <15% total energy from total sugar (%) | Sodium <50 mg/100 kcal and <50 mg/100gd (%) | Energy density ≥60 kcal/100ge (%) | Protein sufficient in mealsf (%) | Total fat within proposed limitg (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dry, powdered and infant cereal/starchy food | ||||||||

| 1.1 | Dry or instant cereals/starch | 75 | 92 | 83 | - | 100 | - | 100 | 100 |

| 2 | Soft-wet spoon-able, ready-to-eat foods | ||||||||

| 2.1 | Dairy-based desserts and cereal products | 12 | 82 | 12 | – | 100 | 100 | 41 | 88 |

| 2.2 | Fruit puree with or without addition of vegetables, cereals or milk | 54 | – | 86 | – | 100 | 64 | – | 100 |

| 2.3 | Vegetable only puree | 67 | 100 | 100 | – | 67 | – | – | 100 |

| 2.4 | Pureed vegetables and cereals | 50 | 50 | 100 | – | 100 | 100 | – | 100 |

| 2.5 | Pureed meal with cheese (but not meat or fish) mentioned in the name | 33 | 67a | 100 | – | 100 | 67 | 100 | 100 |

| 2.6 | Pureed meal with meat or fish mentioned as first food in product name | 27 | 80 | 100 | – | 93 | 53 | 73 | 100 |

| 2.7 | Pureed meals with meat or fish (but not named as the first food in product name) | 17 | 83 | 83 | – | 83 | 33 | 50 | 100 |

| 3 | Meals with chunky pieces | ||||||||

| 3.1 | Meat, fish or cheese-based meal with chunky pieces | 30 | 87h | 65 | – | 52 | – | 65 | 100 |

| 3.2 | Vegetable-based meal with chunky pieces | 63 | 100 | 88 | – | 75 | – | 88 | 88 |

| 4 | Dry finger foods and snacks | ||||||||

| 4.1 | Confectionery, sweet spreads and fruit chewsi | 0 | 40 | 10 | 10 | 30 | 50 | – | 80 |

| 4.2 | Fruit (fresh or dry whole fruit or pieces) | 100 | – | 100 | – | 100 | 100 | – | 100 |

| 4.3 | Other snacks and finger foods | 2 | 34 | 47 | 61 | 47 | 52 | – | 92 |

| Total | 33 | 63 | 68 | 54 | 77 | 62 | 69 | 96 | |

- a Recommendations for trans fatty acids were unable to be assessed as part of this analysis.

- b Dried or pureed fruit is within proposed limit if: dried or powdered fruit is ≤10% by weight for dry or instant cereals/starch; fruit puree is ≤5% by weight with a maximum of 2% from pureed dried fruit for dairy-based desserts and cereal products, pureed meals and meals with chunky pieces; they have no added fruit or fruit puree for vegetable only puree and pureed vegetables and cereals; does not contain any blended, pulped, pureed or powdered 100% fruits (including dried fruit which has been pureed) for confectionery, sweet spreads and fruit chews, and other snacks and finger foods.

- c The following listed ingredients have been classed as added sugars and sweeteners for this analysis: sugar/cane sugar, fruit paste, fruit juice, fruit juice concentrate, fruit gel, coconut sugar, dried yoghurt, other sugars (alcohol), other sugars (glucose, syrup, etc.), intense sweeteners (eg mannitol, sorbitol, isomalt), lactose, galactose, glycerin, nonnutritive sweeteners.

- d Or <100 mg sodium/100 kcal and 100 mg sodium/100 g if cheese meal; or only <50 mg/100 kcal if dry cereal.

- e An upper energy density limit of ≤50 kcal/100 g per serve was required for sub-categories 4.1 (confectionery, sweet spreads and fruit chews), 4.2 (fruit) and 4.3 (other snacks and finger foods).

- f Protein is sufficient if: total protein is <5.5 g/100 kcal for dry or instant cereals/starch; ≥2.2 g dairy protein/100 kcal (if dairy product is first or only ingredient in name) for dairy-based desserts and cereal products; total protein is ≥3 g/100 kcal and protein from dairy is ≥2.2 g/100 kcal for pureed meals with cheese (but not meat or fish) mentioned in the name; first-named protein is ≥10% by weight of the total product and total protein is ≥4 g/100 kcal from the named sources (of which ≥2.2 g/100 kcal protein is from dairy if cheese is mentioned in front-of-pack name) for pureed meals with meat or fish mentioned as first food in product name; the protein source mentioned in the product name is ≥8% by weight of the total product, each named protein is not less than 25% by weight of total named protein and total protein is ≥3 g/100 kcal from all sources (of which ≥2.2 g/100 kcal protein is from dairy if cheese is mentioned in the front-of-pack name) for pureed meals with meat or fish (but not named as the first food in product name); total protein is ≥3 g/100 kcal from all protein sources, or ≥4 g/100 kcal if protein source is named as first food (of which ≥2.2 g/100 kcal protein is from dairy if cheese is mentioned in the front-of-pack name), each named protein is not less than 25% by weight of total named protein, and protein source mentioned in the product name is ≥8% by weight of the total product, or ≥10% if protein is named as the first food(s) in front-of-pack name, for meat, fish or cheese-based meals with chunky pieces; total protein is ≥3 g/100 kcal for vegetable-based meals with chunky pieces.

- g Total fat is within proposed limit if: total fat is ≤4.5 g/100 kcal for dry or instant cereals/starch, dairy-based desserts and cereal products, fruit puree with or without addition of vegetables, cereals or milk, vegetable only puree, pureed vegetables and cereals, pureed meals with meat or fish (but not named as the first food in product name), meals with chunky pieces (except where protein source is named as the first food), and dry finger foods and snacks; total fat is ≤6 g/100 kcal for pureed meals with cheese (but not meat or fish) mentioned in the name where cheese is mentioned first, pureed meals with meat or fish mentioned as first food in product name, and meat, fish or cheese-based meals with chunky pieces where the protein source is named as the first food.

- h Where % of fruit was not listed, it was assumed the product contained levels of dried or pureed fruit that exceeded the WHO Europe proposed threshold.

- i Under the nutrient profile model (NPM) recommendations, confectionery, sweet spreads and fruit chews should not be marketed as suitable for infants and young children <36 months.

In the absence of a current regulatory definition of added sugars in Australia, the Public Health England (PHE) definition of free sugars was used to determine whether each CAF product contained added sugar or not.17 We chose to use this broader definition of added sugars rather than the narrower definition applied in the WHO Europe NPM given the call from public health advocates that any improvements to sugar labelling on Australian products capture all food components covered by the term ‘free’ sugars to genuinely inform consumers about sugars that are harmful to health and promote healthier choices.18 The PHE definition includes all monosaccharides and disaccharides added to foods plus sugars naturally present in honey and syrups. It also includes all sugars naturally present in fruit and vegetable juices, concentrates, purees, pastes, powders and extruded fruit and vegetable products (but excludes those naturally present in fresh, dried, stewed, canned and frozen fruit and vegetables). Lactose and galactose added as an ingredient are captured in this definition as well.

All analyses were conducted using Stata/MP V.16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Simple descriptive statistics (percentages) are reported with differences between infant and toddler foods tested using chi-square analysis.

3 RESULTS

Of the 250 CAF products identified, 177 were infant foods and 73 were toddler foods. Most infant foods (71%) were marketed to those aged at least 6 months. As shown in Table 1, the predominant WHO food category represented among infant products was soft-wet spoon-able, ready-to-eat foods (71%), with dry finger foods and snacks (13%), meals with chunky pieces (10%) and dry, powdered and infant cereal/starchy food (7%) much less frequent. For toddler products, dry finger foods and snacks (71%) was the most prevalent category, with the remaining toddler products classified as either meals with chunky pieces (19%) or soft-wet spoon-able, ready-to-eat foods (10%). None of the CAF products fit into the juices and other drinks category.

3.1 Comparison to WHO Europe proposed nutrient composition standards

Table 2 displays the percentage of CAF products meeting each of WHO Europe's seven nutrient composition standards in their proposed NPM both overall and by food category. Almost two-thirds (63%) of products were compliant with proposed limits for dried or pureed fruit; however, this percentage did vary across categories ranging from 100% for vegetable only puree products to as low as 34% for other snacks and finger foods. Similarly, while 68% of products did not include any added sugars or sweeteners as recommended, some categories (eg dairy-based desserts and cereal products, 12%) performed considerably worse than others on this criterion. Just over half (54%) of dry finger foods and snacks contained less than 15% total energy from total sugar as specified in the NPM. Overall, 55% of CAF products (and only 12% of dry finger foods and snacks) met all the sugar-related standards (ie dried/pureed fruit limit, no added sugars/sweeteners and/or <15% total energy from total sugar) for their category (data not shown in table).

Sodium content was within proposed limits for around three quarters (77%) of CAF products, although there was a tendency for meals with chunky pieces (especially those that were meat, fish or cheese-based) and (nonfruit) finger foods and snacks to be less compliant. Sixty-two percent of products subject to energy density limits were within the designated bounds, with notable fluctuations within the soft-wet spoon-able, ready-to-eat foods category (range: 33%-100%). Protein content was found to be sufficient in 69% of products where protein recommendations were applicable, but this dropped to just 41% for dairy-based desserts and cereal products. Nearly all products (96%) met total fat limits recommended by WHO Europe with minimal variation across categories (range: 80%-100%). When considering the proposed nutrient composition standards collectively, just one-third (33%) of CAF products met all the recommendations for their category.

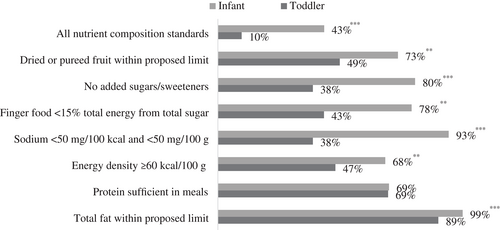

As illustrated in Figure 1, infant foods were more likely than toddler foods to be within the proposed limits for dried or pureed fruit (73% vs 49%; χ2[1] = 9.34, P = .002), sodium (93% vs 38%; χ2[1] = 88.39, P < .001), energy density (68% vs 47%; χ2[1] = 7.16, P = .007) and total fat (99% vs 89%; χ2[1] = 13.00, P < .001). In addition, compared to toddler foods, a higher proportion of infant foods contained no added sugars or sweeteners (80% vs 38%; χ2[1] = 40.26, P < .001) and less than 15% total energy from total sugar for dry finger foods or snacks (78% vs 43%; χ2[1] = 7.90, P = .005). Although infant foods were more compliant than toddler foods with all the sugar-related standards for their category (69% vs 22%; χ2[1] = 46.18, P < .001), this same difference was not apparent when focusing specifically on the dry finger foods and snacks category (13% vs 12%; P = .853; data not shown in figure). The percentage of products with sufficient protein content did not vary between infant and toddler foods (both 69%; P = .977). Overall, around 4 in 10 infant foods (43%) met all proposed nutrient composition standards for their category whereas only 1 in 10 toddler foods (10%) achieved this (χ2[1] = 25.92, P < .001).

3.2 Added sugars in CAFs for infants and toddlers

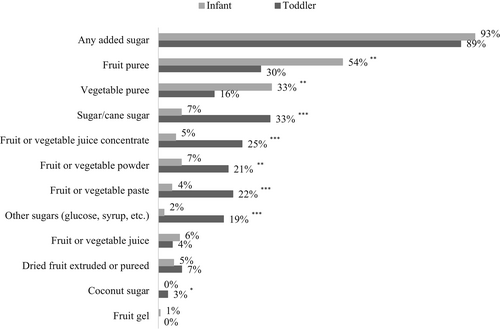

Around 9 in 10 (92%) CAF products assessed contained added sugar (according to the PHE definition of ‘free’ sugars). As Figure 2 highlights, the most common source of added sugar in infant foods was fruit puree (54%) followed by vegetable puree (33%), while all other types of added sugars were only found in a small percentage of infant foods (7% or less). Sugar/cane sugar (33%) was the most common source of added sugar in toddler foods followed closely by fruit puree (30%) and fruit or vegetable juice concentrate (25%). Toddler foods were more likely to contain sugar/cane sugar, fruit or vegetable juice concentrate, fruit or vegetable powder, fruit or vegetable paste, other sugars (glucose, syrup, etc.) and coconut sugar whereas infant foods were more likely to contain fruit and vegetable puree (all P < .05). The percentage of products containing fruit puree but no other type of added sugar was significantly higher in infant foods compared to toddler foods (33% vs 8%; χ2[1] = 16.35, P < .001). Conversely, the percentage of products containing added sugar without fruit puree was significantly higher in toddler foods compared to infant foods (59% vs 39%; χ2[1] = 8.29, P = .004).

4 DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare Australian CAF products for infants and toddlers to the WHO Europe NPM which proposes criteria for nutritionally appropriate foods for infants and young children. We found that two in three (67%) Australian CAF products do not meet all the recommended nutrient composition standards for their category. This is in line with pilot test results from 2018 in seven European countries which found the failure rate against all draft NPM compositional thresholds ranged from 58% in Estonia to 85% in Hungary; however, it is important to note that, unlike the current study, their analyses did not assess compliance with dried or pureed fruit limits nor consider upper limits for energy density per serve for finger foods.12 When looking at each standard separately, there is considerable room for improvement in the nutritional profile of Australian CAF products across the board excepting total fat content, with the most significant failure observed among (nonfruit) dry finger foods and snacks for their high sugar content (46% of these products derived ≥15% of their energy from total sugar). Although the WHO Europe NPM states that no CAF products should be marketed as suitable for infants less than 6 months of age,12 29% (n = 51) of infant foods identified in this study were labelled for those aged 4+ months or 5+ months. This is concerning as the availability of such products may prompt early introduction of foods inappropriate for young infants and undermine the importance of breastfeeding.1

On the whole, infant foods performed significantly better than toddler foods when compared to the WHO Europe proposed nutrient composition standards, particularly with regard to sodium content. In respect of sodium, this is unsurprising given that regulation under the Food Standards Code sets compositional limits for sodium in infant foods, whereas toddler foods are not subject to these same protections.19 This shows how effective a compositional limit is in limiting nutrients of concern in infant foods and highlights the need for introducing regulation of sodium in toddler foods.

Stronger regulation of both infant and toddler foods is warranted given that over half of products marketed to infants and 90% of toddler products did not meet at least one of WHO Europe's proposed nutrient composition standards for their category. For Australian CAFs to meet WHO Europe recommendations, the regulation of both infant and toddler foods should focus on setting a limit on harmful sugars, setting energy density thresholds to make sure these products are nutritious, ensuring there is sufficient protein in meals, and extending the sodium limits for infant CAFs to toddler CAFs.

The majority (92%) of Australian CAF products identified were found to contain added sugar when applying the PHE definition of ‘free’ sugars. This contrasts with results from an analysis of the nutrient properties of Australian commercial infant and toddler foods available as of August 2019 where 40% of products contained ‘free’ sugars.4 It is likely that this discrepancy is due to the narrower definition used in the previous study (ie added forms of dextrose, fructose, sucrose, lactose, sugar syrups and fruit syrups plus fruit pastes and the sugar component of honey, fruit juice and fruit juice concentrates) which did not include fruit purees or vegetable purees/juices/juice concentrates/pastes. Indeed, when we exclude these food components from our definition, the percentage is comparable (43%). Although, as expected, fruit puree was the most common source of added sugar found in infant products, more than half (60%) of products marketed as suitable for children under 12 months included other sources of added sugar. Our finding that 89% of toddler products contain added sugar is higher than the 66% figure reported in a separate audit of Australian toddler food products conducted in November 2019 by McCann et al.3 Possible explanations for this difference may be their wider sampling frame and subsequent larger product capture (154 toddler foods were included in the latter study vs 73 in the current study) as well as their definition of added sugar not including vegetable purees or juices. As young children have a predisposition for sweet tastes,20 government policy should focus on limiting the added sugar content in CAFs for both infants and toddlers to ensure they are not exposed to foods that are unnecessarily sweet or have an underlying sweet taste. Implementation of added sugar labelling on packaged foods, which is presently being considered in Australia and New Zealand,14 would also importantly empower parents and caregivers to make healthier (and more diverse tasting) choices for their children during the crucial early years when taste preferences are being shaped.21 However, to genuinely inform parents and caregivers, a broad definition of added sugars—that captures all processed fruit and vegetable sugars—needs to be used in any update to labelling in Australia, especially given how common they are in infant and toddler foods.

Some study limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sampling frame only included the three main supermarket chains and in-store data collection was restricted to retail outlets in a single suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, chosen based on convenience rather than them being large flagship stores. As such, not all available CAF products for infants and toddlers on the Australian market were captured—250 products were included in the current study compared to the 414 products (including yoghurts) that were identified in the August 2019 audit conducted by Moumin et al in Adelaide, South Australia.4 Although we would expect many missing products to be less popular brands, product lines and/or flavours, it will be important for future studies to validate our findings using a more rigorous sampling approach. Second, it was not possible to determine levels of compliance with the WHO Europe NPM recommendation that industrially produced trans fatty acids should not be included in CAFs for infants and toddlers as Australian products are not required to indicate trans-fat content on the nutrition information panel except if making a nutrition content claim in relation to fats or cholesterol.22 However, given that Australians (aged 2+ years) obtain on average only 0.6% of their daily energy intake from trans fatty acids23 – which includes both artificial and those that occur naturally in some meat and dairy products – it is unlikely that the percentage of products meeting all of the proposed nutrient composition standards for their category would have decreased markedly if we were able to include this criterion in our assessment. A key strength of the current study is that it is the only Australian audit to directly compare the nutritional profile of infant versus toddler foods.

In conclusion, these study findings highlight that many Australian CAF products for children <36 months, particularly those promoted as suitable for toddlers, do not align with the NPM requirements outlined by WHO Europe for nutritionally appropriate foods for infants and toddlers. While the positive impact of existing Australian regulations for infant foods was apparent, there is a crucial need for both stronger compositional standards as well as the extension of these protections to toddler foods, particularly in relation to sodium. Stronger compositional standards to limit harmful sugars, thereby reducing energy density, and to ensure meals contain sufficient protein are needed for both infant and toddler CAFs. Guidance is also needed to ensure that the flavour profile of these products is broad and they are not unnecessarily sweet tasting. Finally, with 9 in 10 CAFs for infants and toddlers containing added sugars that are harmful to health, policy action to provide parents and caregivers with the necessary tools to identify and avoid these products (eg through added sugar labelling on packaged foods) would be an important step towards setting young Australians on the path towards longer-term healthy eating patterns.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have contributed to the present paper by being involved in conceiving and designing the study or in analysis and interpretation of data, and in writing and revising the paper.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors gratefully acknowledge Emily Falduto and Emma Glassenbury for their assistance in the early stages of drafting this manuscript and interpreting the data.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.