What is the effect of a brief intervention to promote physical activity when delivered in a health care setting? A systematic review

Abstract

Issue Addressed

What are the effects of a brief intervention to promote physical activity (PA) delivered in a health care setting other than primary care?

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and PsycINFO were used to identify randomised controlled trials which evaluated the effect of brief interventions to increase PA, delivered in a health care setting. Review outcomes included subjectively or objectively measured PA, adherence to prescribed interventions, adverse events, health-related quality of life, self-efficacy and stage of change in relation to PA. Where possible, clinically homogenous studies were combined in a meta-analysis.

Results

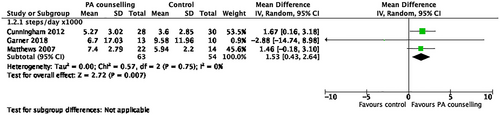

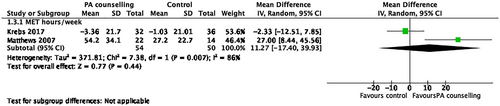

Twenty-five eligible papers were included. Brief counselling interventions were associated with increased PA compared to control, for both self-reported PA (mean difference 34 minutes/week, 95% confidence intervals [95% CI] 9-60 minutes), and pedometer (MD 1541 steps/day, 95% CI 433-2649) at medium term follow up.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that some brief interventions to increase PA, delivered in the health care setting, are effective at increasing PA in the medium term. There is limited evidence for the long-term efficacy of such interventions. The wide variation in types of interventions makes it difficult to determine which intervention features optimize outcomes.

So What?

Brief counselling interventions delivered in a health care setting may support improved PA. Clinicians working in health care settings should consider the implementation of brief interventions to increase PA in vulnerable patient groups, including older adults and those with chronic illness.

1 INTRODUCTION

Physical inactivity is responsible for up to 10% of major non-communicable diseases worldwide, including coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes,1 and dementia,2 and responsible for 9% of premature mortality.1 While overwhelming evidence indicates regular physical activity (PA) has important health benefits, more than half of Australian adults do not meet PA guideline.3 For those aged over 75 years only 25% meet PA recommendations,3 despite clear benefits of PA for disease prevention and maximizing functional independence.4 Those who suffer from chronic disease are also less likely to participate in regular PA5-8 despite its importance in delaying illness progression and managing symptoms.9

Effective interventions to increase population PA levels have been identified in a range of populations, including older adults and those with chronic disease. Health coaching has a small effect on PA in people over 60 years old.4 A systematic review of interventions to increase PA in community-dwelling older adults found interventions tested among healthier participants had larger effects than those tested among chronically ill populations.10 Education interventions to increase PA in adults with chronic illness have been moderately effective, however, there is considerable heterogeneity across studies in the magnitude of effect.11

PA counselling can support increased PA, and ideally takes place “in settings with the chance to reach ‘difficult’ subgroups of sedentary adults” (p. 375).12 Brief interventions involve verbal advice or encouragement, varying from basic advice to more detailed counselling, and are typically delivered face-to-face, over one or more sessions.13, 14 To date, systematic reviews regarding brief PA intervention programs are predominantly limited to interventions delivered in primary care. A systematic review examining nutrition and PA counselling interventions to reduce cardiovascular disease risk, delivered almost exclusively in primary care, reported a modest increase in PA with intervention compared to no-intervention or usual care control group.15 While primary care studies have shown brief physician advice can increase PA levels moderately in the short-term,16, 17 long-term results are less promising.18 Health care settings other than primary care may also offer the potential to reach these “difficult subgroups” during times of health crisis and recovery, where new motivation may exist to engage in PA counselling and with access to trusted, skilled clinicians. However, the effect of brief interventions to promote PA when delivered in alternative health care settings, or by health professionals other than primary care practitioners, remains unclear.

The aim of this systematic review was to investigate the effect of a brief intervention to promote PA, when delivered in a health care setting other than primary care. The review objectives were to describe brief interventions to promote PA delivered in a variety of health care settings; and, to examine the effectiveness of these brief interventions in patients accessing the health care system, including older adults and those with chronic illness. As per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, a protocol was registered prior to review commencement (PROSPERO CRD42019114544).

2 METHOD

2.1 Criteria for considering studies for this review

2.1.1 Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster-RCTs published in peer reviewed journals were considered for inclusion. Only English language publications were considered due to resource limitations. No date restrictions were imposed.

2.1.2 Types of participants

Studies that included adults, aged over 18 years, being managed in a health care setting, were included. Studies including both children and adults were considered, provided at least 80% of the participants were aged over 18 years. Studies based in the primary care setting were excluded, as these have been examined in reviews previously.14, 19, 20 Studies whose participants had pre-existing medical conditions were included, provided they remained able to participate in PA.

2.1.3 Types of interventions

This review investigated brief counselling interventions, employed to promote increased participation in daily PA, when delivered from the inpatient or outpatient health care setting.

For the purpose of this review “brief interventions” were defined according to the NICE guidelines13 for “brief advice,” being: “verbal advice, discussion, negotiation or encouragement, with or without written or other support or follow-up. This may vary from basic advice to a more extended individually focused discussion.” While brief interventions are typically of 5 to 30-minutes duration,14 “brief interventions” of longer duration were not excluded. Studies were excluded if the intervention included more than three face-to-face sessions. Interventions including PA advice in combination with other education and lifestyle advice were included.

2.1.4 Types of outcome measures

The primary outcome of this review was PA level. Studies were included if they measured PA levels either subjectively (ie, self-report or activity diary) or objectively (ie, activity monitor or pedometer), as a primary or secondary outcome. Measures of PA included, but were not limited to, total energy expenditure (ie, Calories or joules), total minutes of PA/week or intensity of PA (ie, activity monitor or self-report).

Studies were not excluded in relation to length of follow-up, rather they were categorized based on time-points for follow-up measures. Those with follow-up of up to 1 month were classified as short-term; greater than 1 month up to 6 months were classed as medium-term; and greater than 6 months were classed as long-term follow up.

Secondary outcomes included: adherence to prescribed interventions; adverse events; health-related quality of life (QoL); self-efficacy and stage-of-change in relation to PA, as measured by standardized assessment tools. Adverse events comprised musculoskeletal injuries, falls, injuries as a result of a fall (ie, fractures or sprains), cardiovascular events and death.

2.2 Search strategy

The search strategy for four electronic databases was developed alongside a research librarian and undertaken from inception to January 2, 2022 (see online supplement).

2.3 Study selection

Two independent reviewers (Emily T. Green and Clare M. Arden/Cathy J. Warren) analysed all titles and abstracts to determine eligibility criteria. Disagreements were resolved via discussion and consensus, with a third author available for arbitration.

2.4 Data extraction

A bespoke data extraction tool was developed (see online supplement). The primary investigator extracted the data and a second reviewer verified this, with disagreements resolved via discussion and consensus, with the option to consult a third reviewer as required.

2.4.1 Assessing for risk of bias

Two reviewers independently assessed the quality and risk of bias of included studies according to the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool.21 A sensitivity analysis was performed excluding studies at high risk of bias for the domains of allocation concealment and assessor blinding. Blinding of participants and those delivering the treatment conditions was not possible in many studies, therefore allocation concealment and assessor blinding were considered particularly influential to risk of bias.

2.5 Data analysis

2.5.1 Measures of treatment effect

Where populations, interventions and outcomes were considered clinically homogenous and outcomes measured on the same scale and reported at the same time point, a meta-analysis was performed using Cochrane statistical package RevMan 5.4.1.22 As the included studies estimated different, yet related, intervention effects, a random effect model was applied. For continuous outcomes, where studies used the same scale to assess the same outcome, treatment effects are expressed as mean differences and 95% confidence intervals.

2.5.2 Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity between studies was determined using the standard chi-square test and I2 statistics. Authors considered I2 < 49% as low heterogeneity, 50% to 74% as moderate heterogeneity and 75% to 100% as high heterogeneity.

2.5.3 Sub-group analysis

A subgroup analysis was performed of inpatient vs outpatient populations. We planned to conduct subgroup analyses examining the effects of the intervention on adults (18-65 years) compared to older adults (>65 years), and comparing modes of intervention delivery; however, missing data and inconsistent methods of reporting between included studies precluded this.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Study identification and selection

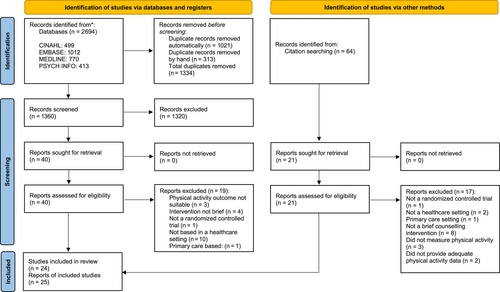

A total of 1360 studies were identified through database searching after removing duplicates. Reference list searching identified 64 additional records. After screening 61 full-text papers, 25 reports representing 24 RCTs met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review (Figure 1).

3.2 Study description

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of included studies. Studies were conducted in the United States (n = 823-30), Australia (n = 631-36), the UK (n = 437-40), Germany (n = 441-44), Canada,45 Poland46 and New Zealand.47 In all included studies, the experimental group received a brief PA counselling session based on behaviour change principles, including some or all of the following elements: education; exercise prescription; goal setting; problem solving to overcome barriers to PA; behavioural reinforcement; and consideration of social supports. Six studies used pedometers31, 33, 39, 40, 45, 48 and seven used exercise diaries28, 31, 33, 41, 43, 46, 48 to encourage self-monitoring. Seven studies included dietary advice alongside PA counselling.26, 27, 29, 34, 37, 38, 45

| Study | Setting | Participants | Intervention | Comparison | Outcome measures | Time to follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baruth et al23 | Recruited from an outpatient cancer centre | n = 32 participants (intervention 20, control 12). All women, early-stage breast cancer survivors. Mean age = 56 years Baseline PA: 6.0 MET h/week |

1 × 30 min in-person counselling session, followed by 5 × 10–15 min telephone counselling calls, over 12 weeks The counselling aimed to increase walking, making use of education and behaviour change principles |

Usual care control group | Physical activity: Community Health Activities Model Program for Seniors (CHAMPS) questionnaire Quality of life: The Medical Outcomes 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) The International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG) QoL Core Questionnaire Fatigue: FACT-fatigue |

12 weeks |

| Brown et al24 | Recruited from an alcohol and drug day treatment program and the community | n = 49 participants (brief advice group 23, aerobic exercise group 26) Including 22 females, 27 males. Mean age = 44 years |

1 × 15–20 min in-person counselling session Discussion of the psychological and physical benefits of exercise, education regarding frequency, duration and intensity recommendations |

Group moderate intensity aerobic exercise, group behavioural treatment, plus a financial incentive system | Alcohol dependence Alcohol use Depressive symptoms Anxiety symptoms Self-efficacy for alcohol abstinence Levels of exercise: TLFB physical activity screen Physical fitness: Cardiorespiratory fitness test |

6 months |

| Butler et al33 | Recruited from a cardiac rehabilitation program | n = 110 participants (brief intervention group 55, control group 55) Including 83 males, 27 females. Mean age = 64 years |

2 × 15 min telephone calls, weeks 1 and 3, shorter calls at weeks 12 and 18. Phone calls focused on behavioural counselling, goal setting and outcome expectancies Pedometer, step calendar and walking safety sheet also provided |

Control group, given generic PA information brochure | Physical activity Active Australia Survey Submaximal cardiorespiratory fitness Self-efficacy for exercise Self-efficacy for exercise Scale Outcome expectancies Behavioural and cognitive self-management use Psychological distress |

6 months |

| Caswell et al37 | Recruited from an outpatient colorectal screening | n = 74 participants (intervention 41, control 33) Including 52 males, 22 females. Mean age = 62.4 years |

1 × 2 h in-person counselling session, followed with 3 personalized mailings, over 12 weeks The session included assessments, general cancer prevention diet and activity education, a personalized program and discussion of social supports |

Usual care control group | Physical activity: 7-day physical activity recall (Scottish physical activity questionnaire-2) Fruit and vegetable intake |

12 weeks |

| Clark et al38 | Recruited from an outpatient diabetes centre | n = 100 participants (*intervention and control group numbers not available) Including 58 men, 42 women. Mean age = 59.5 years Participants had diabetes approximately 8 years and typically had one or more chronic illnesses |

1 × 30 min in-person counselling session, followed by 3 × 10 min telephone calls at 1, 3 and 7 weeks following the intervention, then further in-person counselling at 12 and 24 weeks The counselling session aimed to develop personalized dietary and physical activity self-management programs, including goal setting and overcoming barriers |

Usual care control group | Physical activity: The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly Questionnaire (PASE) Diabetes self-management Dietary fat intake Fat-related dietary habits Weight, BMI (body mass index), waist Blood markers: total serum cholesterol, total high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), triglycerides, haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) |

12 months |

| Collins et al25 | Recruited from a non-invasive vascular laboratory prior to discharge to the community | n = 44 participants with peripheral arterial disease (intervention 18, control 26) Including 26 men, 18 women. Mean age 67.4 years |

1 × 15–20 min in-person counselling session. Counselling involved education regarding peripheral arterial disease (PAD), the role of walking for exercise to manage PAD, overcoming barriers and an exercise prescription | Video-watching comparison/control group Video content: overview of PAD |

Physical activity: Part B of the NHIS WIQ (walking impairment questionnaire) Leg symptoms |

12 weeks |

| Cunningham et al40 | Recruited from a single acute health board (in Scotland) | n = 58 participants with intermittent claudication (IC) (intervention 28, control 30). Including 39 men and 19 women. Mean age 65.3 years | 2 × 1 h, home-based in-person counselling sessions Sessions included; education about IC, walking and health, an individualized walking program, discussion of barriers and strategies to overcome |

Usual care control group | Physical activity: Daily step by pedometer Quality of life: Disease specific: Intermittent Claudication Questionnaire General: WHOQoL-BREF Perception of pain-free walking distance. Acceptability of the intervention |

4 months |

| Cunningham et al39 | Recruited from a single acute health board (in Scotland) | n = 58 participants with intermittent claudication (IC) (intervention 28, control 30). Including 39 men, 19 women. Mean age 65.3 years | 2 × 1 h home-based in-person counselling sessions Sessions included; education about IC, walking and health, an individualized walking program, discussion of barriers and strategies to overcome |

Usual care control group | Physical activity: Daily step by pedometer Quality of life: Disease specific: Intermittent Claudication Questionnaire General: WHOQoL-BREF Perception of pain free walking distance. Acceptability of the intervention |

2 years |

| Freene et al35 | Recruited from an outpatient physiotherapy clinic | n = 40 participants (intervention 20, control 20) Including 33 women, 7 men. Mean age 44 years |

1 × very brief face-to-face consultation (<5 min), including provision of a brochure and brief discussion of PA guidelines. 4 physiotherapist lead PA measurements, baseline, weeks 6, 12 and 18 | The second group received the same very brief intervention with only two measurement sessions, baseline and 18 weeks | Physical activity: ActiGraph activity monitor Active Australia Survey Functional aerobic capacity: STEP tool Quality of life: AQoL-6D |

18 weeks |

| Furber et al31 | Recruited from cardiac rehab non-attendees | n = 215 participants (intervention 104, control 111) Including 151 men, 64 women. Mean age 66 years | 4 × 15 min telephone counselling sessions at weeks 1,3,12 and 18, plus mail-based follow up Phone calls focused on increasing self-efficacy, increasing outcome expectancies, establishing physical activity goals and behavioural reinforcement |

Usual care control group | Physical activity: Active Australia Questionnaire Self-efficacy for exercise scale Outcome expectation for participation in Physical Activity Self-management strategy use Psychological distress |

6 months |

| Garner et al45 | Recruited from an early inflammatory arthritis clinic | n = 28 participants with a new diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (intervention 14, control 14). Including 5 men and 23 women. Mean age 47 years | 1 × 2 h in-person first counselling session, followed by a 90 min second session Treatment targeted both dietary and physical activity advice |

Usual care control group | Physical Activity: Pedometer step count Quality of life: Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) Physician/patient global evaluation score (VAS 0-100) Nutritional intake Tender and swollen joint counts |

6 months |

| Green et al36 | Recruited from an outpatient rehabilitation program | n = 35 participants (intervention 18, control 17). Including 16 men, 19 women. Mean age 71 years | 1 × 15–45 min face to face, stage of change based, PA education and counselling session. Treatment addressed goal setting, problem solving and social support for behaviour change | Control group, given generic PA information brochure | Physical activity: GENEActiv™ armband activity monitor Feasibility Quality of life: AQoL-5D Stage of change for exercise: Exercise Stage Assessment Questionnaire Self-efficacy for exercise: The self-efficacy for exercise scale |

3 months |

| Jackson et al26 | Recruited from prenatal care practices | n = 321 pregnant women (intervention 158, control 163). Mean age 26.5 years | 1 × 10-15 min interactive Video Doctor teaching and counselling session, about nutrition, exercise, and weight gain | Usual care control group | Physical activity: Self-reported Min/week of PA Dietary: Servings per day fruit and vegetable Food knowledge, knowledge of guidelines, weight gain |

6 weeks |

| Jones et al47 | Recruited from an inpatient coronary care unit prior to discharge to the community | n = 70 participants (intervention 35, control 35) Including 49 men and 21 women. Mean age 61 years |

1 × 15 min animated psycho-educational intervention delivered on an iPad. The intervention focused on the pathogenesis of acute coronary syndrome and informing participants about behaviours to maintain their health | Usual care control group | Physical activity: subjective min per week Adherence Illness perceptions Medication Beliefs Cardiac anxiety Satisfaction with intervention Patient drawings of the heart |

7 weeks |

| Krebs et al27 | Recruited from an outpatient cancer centre | n = 86 patients who had completed their treatment for either breast or prostate cancer (intervention 44, control 42). Including 4 males, 82 females. Mean age 59.8 years | 1 × 60 min e-health program provided via DVD. The program focused on education and behaviour change counselling, to meet Physical activity guidelines and reduce sedentary time | Usual care control group (which included in-person brief advice and counselling) | Physical activity: Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire Fruit and vegetable intake Acceptability and feasibility of the intervention (qualitative feedback) |

12 weeks |

| Matthews et al28 | Recruited from an outpatient cancer clinic | n = 36 breast cancer survivors (intervention 22, control 14). Including women only. Mean age 53.5 years | 1 × 30 min in home counselling session, plus 5 × 10-15 min follow up telephone calls over 12 weeks Behavioural counselling focused on goal setting, physical activity safety, motivators, barriers and social support |

Usual care control group | Physical activity: Self-report logs, pedometer steps, RPE, CHAMPS, Actigraph activity monitor Body weight and composition Dietary patterns |

12 weeks |

| Osborn et al29 | Recruited from an outpatient, primary care clinic | n = 91 type two diabetics (intervention 48, control 43). Including 23 men, 68 women. Mean age 57.6 years | 1 × 90 min in-person counselling session. The session focused on education, motivation and behaviour change, in relation to diet, health management and physical activity | Usual care control group |

Food label reading Diet adherence Glycaemic control |

12 weeks |

| Redfern et al34 | Recruited from coronary care in a tertiary referral hospital | n = 144 acute coronary syndrome survivors (intervention 72, control 72) Including 107 men, 37 women. Mean age 64.5 years |

1 × 60 min initial consultation followed by 3 × phone calls over 3 months Risk factor screening, goal setting, education regarding management options. Including lowering cholesterol, blood pressure, increasing PA and smoking cessation |

Usual care control group | Physical activity: 7 day International PA Recall Questionnaire Quality of life: Short form 36 Prevalence of coronary risk factors Depressed mood Participant's knowledge of own risk factors Medical consultation frequency |

12 month |

| Sangste et al48 | Recruited from an outpatient cardiac rehabilitation program | n = 313 participants (intervention 157, control 156). Mean age 64.2 years | Intervention #1 4 × 15 min telephone counselling sessions, plus mail-based follow up Phone calls focused on increasing self-efficacy, increasing outcome expectancies, establishing physical activity goals and behavioural reinforcement |

Intervention #2 “Healthy weight intervention” 6x brief telephone counselling sessions, plus mail based follow up. Phone calls focused on optimizing BMI via dietary and physical activity advice |

Physical activity: Self-reported PA Self-reported sedentary time Self-reported weight and BMI |

6–8 months |

| Scholz et al41 | Recruited from an inpatient cardiac rehabilitation unit prior to discharge to the community | n = 198 participants with coronary heart disease (intervention 103, control 95). Including 163 men and 35 women. Mean age 58.5 years | 1 × 15 min in-person “individual planning session”, to develop written action plans and coping plans in relation to exercise. Weekly mail out diaries for 6 weeks | Usual care control group | Physical activity: IPAQ Depressive symptoms Intentions Goal attainment Health status BMI |

12 months |

| Sniehotta et al43 | Recruited from three inpatient cardiac rehabilitation centres prior to discharge | n = 240 participants (unclear how many participants in each group) Including 195 men, 45 women. Mean age 58 years |

Intervention #1 Planning group; one face-to-face planning session, completed worksheet for action plans and coping plans Intervention #2 Planning plus diary group; as above, plus completion of a weekly diary for 6 weeks after discharge |

Usual care control group | Physical activity: Kaiser Physical Activity Survey Self-efficacy for exercise: Self-efficacy for Exercise Scale Planning Action control |

4 months |

| Sniehotta et al42 | Recruited from an inpatient cardiac rehabilitation unit prior to discharge to the community | n = 246 participants with coronary heart disease (intervention #1 81, intervention #2 71, control 94). Including 165 men, 46 women. Mean age 59.3 years | Intervention #1 1 × 30 min in-person ‘individual planning session’, to develop written action plans in relation to exercise Intervention #2 1 × 30 min in-person ‘individual planning session’, to develop written action plans and coping plans in relation to exercise |

Usual care control group + alternate intervention group | Physical activity: Self-reported PA Cycling instead of car or public transport use Self-efficacy for PA Risk perceptions Outcome expectancies Behavioural intentions |

2 months |

| Wolkanin-Bartnik et al46 | Recruited from an outpatient cardiology clinic | n = 115 over 60-year-old participants with stable coronary artery disease (intervention 59, control 56). Including 97 men, 18 women. Mean age 67.5 years | 1 × in-person counselling session, including education about recommendations and parameters for safe exercise. An exercise guidebook was provided, and participants were offered a doctor phone call to discuss any concerns | Usual care control group | Physical activity: Self-reported PA: modified Global PAQ. Adherence/compliance Presence of atherosclerosis risk factors Incidence of cardiovascular events |

12 months |

| Vickers et al30 | Recruited from an outpatient Cardiovascular Health clinic | n = 509 cardiovascular health clinic attendees (intervention 217, control 292). Including 351 men and 158 women. Mean age 61.2 years | Participants were asked to watch a 43 min DVD which provided education and behaviour change strategies, to initiate and maintain regular physical activity | Usual care control group | Physical activity: IPAQ Self-efficacy for exercise SOC for exercise Behavioural change Outcome expectations for exercise Usage and opinions of DVD |

6 weeks |

| Ziegelmann et al44 | Recruited from outpatient orthopaedic rehabilitation | n = 373 participants with musculoskeletal and orthopaedic diseases and injuries (intervention 186, self-administered control 187). Including 140 men, 233 women. Mean age 45.7 years | Interviewer-assisted planning: 10 min face-to-face assistance to complete an action planning sheet, interviewer used motivational interviewing skills and empathic listening |

Self-administered planning: Participants self-completed the same planning sheet as intervention group Experimenter was present however repeated basic instructions only |

Physical activity: Duration, intensity and frequency/week Self-efficacy Subjective physical health |

6 months |

- IPAQ, international physical activity questionnaire; TLFB, alcohol timeline follow back.

Thirteen studies examined a single session brief intervention,24-27, 29, 30, 35, 36, 42-44, 46, 47 with four using technology for delivery26, 27, 30, 47 (i-pad, DVD, computer program). Nine studies included a single brief counselling session with follow up by either mail or phone call.23, 28, 31-34, 37, 38, 41 Three studies involved two in-person counselling sessions.39, 40, 45 The brief counselling sessions in the included studies ranged in duration from 5 minutes35 up to 2 hours,45 with the longer session also including nutrition education and counselling. Follow-up length ranged from single session interventions with no follow-up24-27, 29, 30, 35, 36, 42-44, 46, 47 to three 30-minute face-to-face sessions combined with three 10-minute phone sessions over 24 weeks.38 The mean duration of follow up was 24 weeks. Interventions were delivered by a range of health professionals, including: students23, 25; an exercise physiologist24; trainee health psychologist39, 40; physiotherapist35, 36, 45; and health counsellor.28 Ten studies33, 34, 37, 38, 41-44, 46, 48 did not specify who delivered the intervention and four26, 27, 30, 47 reported interventions delivered via electronic devices.

Five of the interventions were delivered in inpatient settings34, 41-43, 47 while 20 studies were based in outpatient settings. Twenty-two trials included participants with a specific medical condition (online supplement). Two trials recruited participants with mixed diagnoses.35, 36 In 18 studies, the control group received no intervention or usual care23, 26-31, 34, 37-43, 45-47; two of these studies42, 43 examined two different brief PA counselling interventions against a usual care group. Four further studies33, 35, 36, 44 compared a brief PA intervention to a control group who received a minimal intervention. Three studies compared a brief PA counselling intervention to another intervention.24, 25, 32

3.3 Outcomes

Outcomes reported were self-reported PA minutes/day (n = 15 studies24-26, 28, 31-33, 35, 37, 38, 41-44, 46, 47), self-reported MET (metabolic equivalent)/day of PA (n = 5 studies23, 27, 28, 30, 34), pedometer steps/day (n = 4 studies28, 39, 40, 45) and PA using activity monitors (n = 3 studies28, 35, 36). Secondary review outcomes reported included: QoL (n = 6 studies23, 34-36, 39, 40, 45); self-efficacy for exercise (n = 7 studies30, 31, 33, 36, 42-44); and, stage of change in relation to exercise (n = 2 studies30, 36). Three studies reported adherence to prescribed walking interventions from patient-reported activity logs23, 28, 46 with mean adherence ranging from 62%46 to 94%.28 While adverse events were assessed in included papers, none were reported in response to the interventions provided. Five studies involved long-term follow up of participants; with follow up ranging from 12 months34, 38, 41, 46 to 2 years.39 The remaining studies reported medium-term follow up (6 weeks to 8 months). One study was reported across two papers, with one describing outcomes at medium-term40 and the other long-term follow up.39

3.4 Participants

Included studies had a total sample of 3527 participants, with mean age from 26 to 72 years. Three trials included women only,23, 26, 28 in the remaining women represented 51% of participants (data not provided n = 2 studies).

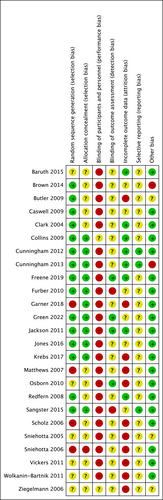

3.5 Methodological quality

All except one study,25 were scored high risk in at least one domain (Figure 2). Four studies28, 41, 42, 45 were scored as high risk for random sequence generation. Blinding of participants to group allocation was achieved in only two studies25, 44; however, due to the nature of the interventions, blinding of the researcher delivering the intervention was not possible. Only four studies26, 29, 35, 36 were low risk for blinding of outcome assessors to group allocation, two studies were high risk,31, 32 while the remaining 19 studies did not specify whether the assessor was blinded. Management of incomplete outcome data led to high risk of bias in eight studies.27-30, 41, 42, 45, 46 Two studies scored high risk for other potential bias, these being unequal payment of participants in each group24 and the potential confounding influence of surgical intervention on outcomes.39 Six authors were contacted for further information, no responses were received. Overall, most of the included studies were rated at a high risk of bias and only very few were rated at a low risk of bias.

3.6 Meta-analysis

Data were able to be pooled for 10 studies, PA outcome data were not sufficiently reported in two studies,43, 44 the remaining studies have been described narratively.

3.6.1 Physical activity

Short term: No studies reported outcomes at 1 month or less.

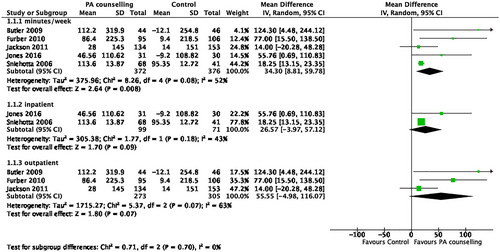

Medium term: Self-reported PA was increased following a brief counselling intervention compared to control (mean difference [MD] 34.3 minutes/week, 95% confidence interval [CI] 9-60 minutes, five studies, 748 participants, I2 = 52%) (Figure 3).26, 31, 33, 42, 47 When studies at high risk of bias for allocation concealment and assessor blinding were excluded, there was no significant difference between groups for self-reported PA (MD 44 minutes/week, 95%CI −5 to 92.5 minutes, three studies, 438 participants, I2 = 51%).26, 33, 47 Effects on steps/day, measured by pedometer, favoured brief PA counselling interventions (MD 1541 steps/day, 95% CI 433-2649, three studies, 117 participants, I2 = 0%) (Figure 4).28, 40, 45 There was no difference between groups for self-reported MET hours/week of PA (MD 11 MET hours/week, 95% CI −17 to 40, two studies, 104 participants, I2 = 86%) (Figure 5).27, 28

Four studies unable to be included in the meta-analysis, reported no difference between groups for PA minutes/week as a result of the brief interventions delivered.25, 35-37 A brief phone-based intervention for PA in breast cancer survivors found intervention group participants had greater subjective energy expenditure from walking for exercise than the control group (effect size [ES] intervention = 3.07; ES control = 0.18; ES between groups = 2.89) at 12-week follow-up.23 When studied in comparison to a weight loss phone counselling intervention in a cardiac rehabilitation population, a brief PA intervention demonstrated significant within group changes for self-reported PA at 6-month follow-up (MD 80 minutes/week, 95% CI 39-120); however, there was no difference between the intervention groups (P = .15).48 When studied alongside an aerobic exercise intervention in an alcohol dependency clinic, a brief intervention demonstrated a within-group change in median self-reported PA minutes/week from 94 minutes (interquartile range [IQR] 0-158) at 12 weeks to 130 minutes (IQR 89-282) at 6 months,24 however there was no difference between groups.

Long term: Two brief interventions in the cardiac rehabilitation setting reported greater PA at 12 months following the intervention. In one study, intervention group participants self-reported a mean 117 (SD 124) minutes/week of PA compared to a no-intervention control group (56 [SD 97] minutes/week; t = 2.94, P < .01).41 In another study, mean PA time at 12 months was 2.8 hours/week for the intervention group versus 2.2 hours/week for the no-intervention control group.46 A third study34 in a coronary care setting also demonstrated self-reported improvement in PA following a brief face-to-face and phone call intervention (mean 1369 [SD 167] METS/kg/min) compared to a usual care control group (mean 715 (103) METS/kg/min; ES 654 (95% CI 264-1040), P < .001). Complete data sets were not available for meta-analysis. A single study39 examined PA steps/day at 12 months in participants with intermittent claudication. The mean difference in daily step count at 1 year was 1374 steps (95% CI 528-2220) and at 2 years was 1630 steps (95%CI 495-2765), however, changes may not all be attributable to the intervention, as 39% of intervention group participants and 67% of control group participants had also undergone revascularisation by 2-year follow-up. A final study38 investigated a brief counselling intervention in a diabetic outpatient clinic and found no difference in PA as reported on the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) questionnaire, at three or 12-month follow-up, compared to a usual care control group.

3.6.2 Secondary review outcomes

There was no difference between groups at any time point for self-efficacy and stage of change, nor for QoL in the short term or the meta-analysis of medium-term outcomes (standardized mean difference [SMD] 0.34, 95% CI −0.31 to 1, three studies, 128 participants, I2 = 69%)35, 36, 40 (online supplement). One single study at medium and long-term follow up reported improvement in QoL favouring the intervention group (WHO-QoL BREF favours intervention at 4-months F (1,55) = 10.04, P = .00240; and SF-36 physical function domain mean 76 (SD 2.7) compared to control 64.3 (2.8), P < .01 at 12 months).34

3.7 Subgroup analysis

In a subgroup analysis, there was no difference between usual care and brief PA counselling in an inpatient setting42, 47 (MD 27 minutes/week [95%CI −4 to 57 minutes], two studies, 170 participants, I2 = 99%) or outpatient setting26, 31, 33 (MD 56 minutes/week [95% CI −5 to 116] three studies, 578 participants, I2 = 63%). Heterogeneity of results was moderate to high.

4 DISCUSSION

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we found some evidence that brief PA counselling, delivered to adults in a health care setting, was effective at increasing PA in the medium term. Brief PA counselling interventions increased mean self-reported PA and mean steps/day when compared to a usual care control group at medium-term follow-up. These findings are consistent with a systematic review examining brief PA interventions in the primary care setting,49 which concluded that brief PA interventions can increase self-reported PA in the short term, with insufficient evidence regarding their long-term impact.

This review demonstrated that the definition of “brief intervention” is broad, with significant variation between included studies in duration of intervention (15 minutes to 2 hours). Six included studies27, 29, 34, 37, 39, 40, 45 examined “brief interventions” which included face-to-face sessions of between one and 2 hours in duration. These longer intervention sessions tended to have less intensive or no follow up, leading to their description as “brief interventions.” Other reviews conducted in primary care14, 49 have also found variation in “brief interventions” which were up to 30 or 40 minutes in length; however, some of the included interventions had a considerable amount of follow up. The use of follow-up beyond the face-to-face intervention may serve to aid participant recall and compliance with advice. The present review found substantial variability in the use of, method, frequency and length of follow up after an initial face-to-face session, ranging from no follow-up to five 15-minute telephone calls over 12 weeks.23, 28 A primary care-based review reported inconclusive evidence on the impact of duration of individual sessions on self-reported PA,49 while also reporting that the use of follow-up sessions might be more important for effectiveness than initial session duration.49

We found a wide variation in brief PA counselling delivery methods, including face-to-face, electronic and telephone, with some studies using a combination of these modes. A number of interventions also included self-monitoring tools like pedometers or walking diaries, and others were supplemented with written information. Because there were too few trials with similar intervention components to pool results, it was not possible to determine if there is any one counselling delivery method or self-monitoring tool that is more effective than another. A review on the effect of health coaching on PA participation in people aged 60 years and over, found telephone-delivered interventions had a small impact on PA (SMD = 0.21; 95% CI 0.11-0.32), compared to face-to-face interventions (SMD = 0.41; 95% CI 0.25-0.58).4 The population included in this large review was recruited from a range of primary and other health care settings, including participants with a range of chronic diseases, meaning these findings may be generalizable to the population studied in this present review. Another review identified several intervention delivery characteristics which positively impact effectiveness, including use of audio-visual media, mailed materials, theoretical basis and a combination of cognitive and behavioural strategies.10 The interventions studied were more time and session intensive than the brief interventions included in our review. Whether these intervention characteristics would have similar effect when used in conjunction with brief interventions remains unclear.

Opportunity exists within the health care setting to target PA interventions to populations vulnerable to inactivity, and to optimally time intervention delivery for each individual to harness existing trust, rapport and expertise to deliver PA interventions. In primary care and the community, brief interventions promoting PA are cost-effective14 and their brief nature makes them feasible to deliver within resource constraints. While the current evidence base supports the use of brief PA interventions in primary care,19 consultations in these settings are time limited; one systematic review has identified that many o brief interventions are too long to be practically conducted in a primary care consultation.49 Evidence to support the use of brief PA interventions in a broader range of settings, and by a range of different health professionals, will increase opportunities for their impact.

5 STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

This systematic review is the first, to our knowledge, to explore the effect of brief counselling interventions to increase PA, when delivered exclusively in health care settings other than primary care. Strengths of this review include its robust methodology, being conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines, and including a comprehensive search strategy determined a priori, no limitations according to date of publication, and the inclusion of only RCTs. Limitations are inclusion of only English-language papers, and the inclusion of several papers with high risk of bias. Most of the studies delivered disease-specific education, some in conjunction with a new diagnosis when the participant may be more motivated for behaviour change for PA. Results must, therefore, be generalized with caution. Only five studies33, 37, 38, 40, 45 examined the long-term impacts of the described brief interventions on PA. While unable to be pooled in a meta-analysis, three studies did demonstrate improved PA outcomes for interventions delivered following acute coronary care or cardiac rehabilitation. Brief interventions may be a useful adjunct to cardiac rehabilitation to increase PA participation. For those unable to attend or participate in cardiac rehabilitation; however, brief interventions may provide a useful alternative. Further high-quality research is required to investigate the long-term effect of brief PA interventions when delivered in a variety of health care settings. This is consistent with findings in the primary care setting.49 Too few studies examined the secondary outcomes of interest in this review to pool data for analysis.

This review was impacted by missing data and inconsistent methods of reporting among included studies. Despite attempting to contact relevant authors, necessary data were not available for a number of studies. Reliance on self-report PA measures in many included trials introduces the potential for recall bias. Self-reported measures have been demonstrated to both over and underestimate PA levels when compared to objective measures.11 In addition, the nature of the included studies made it difficult to conceal participant knowledge of group allocation. This lack of blinding combined with the use of self-report PA measures, leaves studies susceptible to the Hawthorne effect.50 Pooling data were only possible for a small number of studies, and in many cases heterogeneity was high, due to significant variation between populations studied and intervention characteristics. Further research is needed, using robust methodology, objective measures of PA and long-term follow-up, to determine the impact of delivering brief counselling interventions in the health care setting to increase PA participation.

6 CONCLUSION

Brief interventions to increase PA, when delivered in the health care setting, are effective at increasing PA in the medium term. Further evidence is required regarding the efficacy of such interventions in the long term. These results are generalizable to adults and older adults with medical conditions, being treated in a variety of inpatient and outpatient settings outside of primary care. We were unable to determine the factors which impacted the success of these interventions. Further high-quality research is required, applying a consistent definition of “brief intervention,” to determine the optimal method of delivery, length and type of follow-up and harnessing the use of objective PA measures.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Emily T. Green, Anne E. Holland and Narelle S. Cox contributed to the review design. Emily T. Green executed the search strategy and completed the data extraction of included studies. Emily T. Green, Clare M. Arden and Cathy J. Warren screened search results and assessed studies for inclusion. Emily T. Green and Cathy J. Warren completed reference list screening and risk of bias assessments, Clare M. Arden and Cathy J. Warren completed risk of bias assessment for the study published by Emily T. Green, NSC and Anne E. Holland. Cathy J. Warren double checked the data extraction. Emily T. Green, Anne E. Holland and Narelle S. Cox interpreted the findings. All authors contributed to the manuscript, read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.