The oral health behaviours and fluid consumption practices of young urban Aboriginal preschool children in south-western Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Abstract

Issue addressed

Australian Aboriginal children have a higher risk of dental caries yet there is limited focus on oral health risk factors for urban Aboriginal preschool children. This study examined the oral health behaviours and fluid consumption practices of young children from an urban Aboriginal community in south-western Sydney, Australia.

Methods

In total, 157 Aboriginal children who were recruited to the “Gudaga” longitudinal birth cohort participated in this study. A survey design was employed and parents responded to the oral health questions when their child was between 18 and 60 months.

Results

Few parents (20%) were concerned about their child's oral health across the time period. By 60 months, only 20% of children had seen a dentist while 80% were brushing their teeth at least once daily. High levels of bottle use were seen up to 30 months. Consumption of sugary drinks was also very high in the early years, although this was replaced by water by 36 months.

Conclusions

While there are some encouraging findings, such as the rates of tooth brushing and increasing rates of water consumption, the findings do highlight the poor uptake of dental services and high levels of bottle usage among urban aboriginal children during their early years.

So what?

Targeted oral health promotional programs are needed in the urban Aboriginal community to better support parents understanding of good oral health practices in the early years and engagement with dental health services.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Early childhood caries and significance

Dental caries, also known as tooth decay, is the most common chronic disease and public health problem affecting infants and preschool children worldwide. In Australia, almost half of all children experience a form of this decay by the age of 6 resulting in increased susceptibility to tooth decay throughout their lives.1 Dental caries is 1 of the most costly chronic diseases in Australia, accounting for around 6.5% ($5.3 billion) of total annual health care expenditure.2 As the first 18 months of life have been recognised as the opportune time to influence long-term oral health,3 an increased importance has been placed on promoting oral health during early childhood. As a result of this, early childhood caries (ECC) has emerged as a central oral health concern in Australia and guidelines have been put in place to try and address this health issue.4 ECC describes the presence of 1 or more decayed, missing, or filled primary teeth in children aged 60 months (5 years) or younger.5 ECC is largely associated with poor fluid consumption practices of infants and toddlers and is commonly referred to as “nursing bottle caries”.6 Evidence suggests that poor childhood oral health is not only a strong predictor of poor adult oral health, but also that ECC has various impacts on the health and well-being of the child.2, 7 Among the many deleterious effects of ECC on concurrent child well-being are aspects related to growth and development, eating patterns, nutritional deficiency and speech, ultimately impairing their overall quality of life from childhood through to adulthood.7

1.2 ECC: An issue for Aboriginal children

Studies on the oral health of Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States of America (USA) have consistently uncovered higher rates of ECC among Indigenous children compared with non-Indigenous children in the same age cohorts.6-8 A particularly high prevalence of poor oral health and ECC is evident in Australian Aboriginal communities, which has had severe implications including hospitalisations for dental conditions.9, 10 A higher prevalence of risk factors among Aboriginal children such as poor diet, low socio-economic status and a greater exposure to environmental and health behaviour risks contributes to this higher prevalence of ECC.9, 11 Evidence from national child health dental surveys shows that nearly twice as many Aboriginal children have experienced early childhood caries accompanied by higher levels of untreated decay in their deciduous (baby) teeth compared to non-Aboriginal children.11, 12 Reports from the Northern Territory identified oral health problems as the most common condition affecting Aboriginal children, with 45%-85% examined (aged 1-8 years) having caries.11, 13 In fact, Indigenous Australian children have up to 5 times the prevalence of early childhood caries as non-Indigenous children in some communities, particularly in remote areas.5, 14

1.3 ECC in Aboriginal children 0-5 years in NSW

There is limited information on the oral health status and practices of urban Aboriginal children in New South Wales (NSW). Even less is known about Aboriginal preschool children with most reports, including the 2007 NSW Child Dental Survey, focusing on Aboriginal children older than 5 years. A recent cross sectional study has tried to address this gap by assessing the oral health of 196 children aged 4-5 years across rural, remote and metropolitan NSW. The study found a high prevalence of untreated dental caries among Aboriginal children, especially from the remote locations.15 More research exploring the oral health practices of Aboriginal children aged 0-5 years in NSW is required to identify suitable strategies to improve oral health in the early years. This study therefore aims to explore the oral health behaviours and fluid consumption practices of young children from an urban Aboriginal community in south-western Sydney, Australia. The study seeks to answer the following questions:

- What are the oral health concerns and behaviours of Aboriginal children in south-western Sydney?

- What are the fluid consumption practices of Aboriginal children in south-western Sydney?

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Sample and setting

A birth cohort of 149 Aboriginal children was recruited from the maternity ward of a major hospital in south-western Sydney, New South Wales, to the “Gudaga” study.16 The children were recruited between May 2005 and October 2007 and were continually followed up every 6 months. Gudaga means “healthy baby” in the language of the local Aboriginal people, the Tharawal people. The Gudaga study was designed to track the health, development and service use of urban Aboriginal children and their families and was conducted in partnership with the Tharawal Aboriginal Corporation and the South West Sydney Local Health District (SWSLHD). Children were eligible for the study if either of the child's biological parents identified as being Aboriginal. Written informed consent was obtained from the children's mothers upon recruitment.

The Gudaga study was set up to follow a cohort of Aboriginal children from birth through the phases of childhood. Data collection occurred every 6 months and included questions on family background including mothers’ education levels, ethnicity, finance, risk behaviours (including alcohol and tobacco use), social support and family functioning, as well as questions about the child, including gestational age, birthweight, growth, development and health. The Gudaga study was designed to be an inclusive study. This gave families the freedom to miss some data collection points (eg when spending time living in the country, or during a family crisis), then return to the study when they were available. It also allowed the study to follow children through changing living situations, for example being placed in out-of-home care. This ethos has enabled the Gudaga study to form strong and lasting relationships with the families and with the community.

2.2 Data collection

Initial data were collected from the antenatal and birth records in the hospital, and a home-based interview at 2-3 weeks post-birth. This was followed by an interview at 6 months of age and then regular 6-monthly interviews thereafter. Questions regarding the child's oral health were asked from 18 months onwards. Data collected from 18 months to 60 months of age are reported here (January 2007-October 2012). Interviews were conducted by the study's Aboriginal project officers who were part of the local community, and were mostly conducted in the child's main place of residence with the child's primary care giver. Due to the inclusive nature of the study, the number of active children in the study is greater than the number of children for which data were collected at any 1 point in time. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of the NSW Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council (621/07 and 679/11), Sydney South West Area Health Service (04/009 and HREC/10/LPOOL/202), University of NSW and by the board of Tharawal Aboriginal Corporation. The study was conducted in accordance with the national guidelines for ethical conduct in Aboriginal health research.17

2.3 Data analysis

All relevant data from the survey were analysed using IBM SPSS statistics version 22.18 To explore the oral hygiene and fluid consumption practices of Aboriginal children, descriptive statistical analyses were used. All data were presented by time point, with categorical variables such as gender and bottle usage presented as frequencies, and continuous variables such as age presented as means with standard deviations.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographics

A total of 149 interviews were conducted at 2-3 weeks post-birth. Between the ages of 18 months and 30 months, 8 new participants were enrolled into the study, making a study total of 157 participants. At 60 months of age, 116 interviews were completed from a total sample of 157, a retention rate of 75%. A total of 138 participants were interviewed between the 18-month and 60-month time points, when the dental questionnaire items were implemented. Throughout this follow-up period, there were a number of drop-ins and dropouts, thus the number of participants at each time point fluctuated, ranging from 115 to 132 participants. Across all time points, mean age of children was slightly higher than target age for survey (0.65-1.39 months older); however, this was anticipated due to difficulty with follow-up of participants. In addition, there were more female children than males (8.8%-17.2% more females). Refer to Table 1 for full information on age and gender of participants.

| Age in months | Gender | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||||||

| Mean | St Dev | Count | % | Count | % | Count | ||

| Time points (months) | 18 | 19.29 | 1.35 | 60 | 45.8 | 71 | 54.2 | 131 |

| 24 | 25.36 | 1.50 | 61 | 46.2 | 71 | 53.8 | 132 | |

| 30 | 31.42 | 1.73 | 58 | 45.7 | 69 | 54.3 | 127 | |

| 36 | 36.89 | 1.81 | 60 | 46.5 | 69 | 53.5 | 129 | |

| 42 | 43.27 | 1.84 | 58 | 46.4 | 67 | 53.6 | 125 | |

| 48 | 49.38 | 1.57 | 56 | 46.3 | 65 | 53.7 | 121 | |

| 54 | 55.57 | 2.13 | 52 | 45.2 | 63 | 54.8 | 115 | |

| 60 | 60.68 | 1.99 | 53 | 45.7 | 63 | 54.3 | 116 | |

3.2 Oral health behaviours

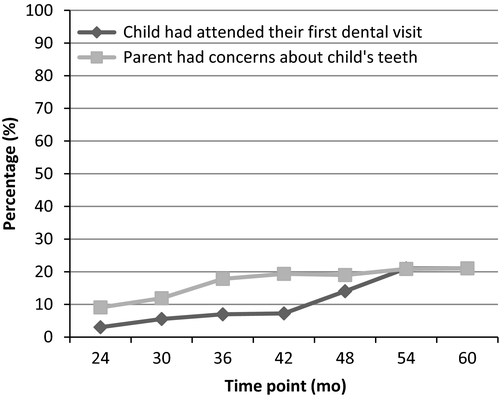

Data relating to parental concerns about the oral health of their children were collected from the 24-month time point up to the 60-month time point. Results highlighted that the majority of parents did not have concerns regarding their child's oral health over the duration of the study; however, the percentage of concerns increased over time. At 24 months of age, fewer than 10% of parents had concerns about their child's teeth. However, by 60 months of age, just over 20% of parents had concerns about their child's teeth (Figure 1). Findings indicated that <5% of children had attended their first dental visit by 24 months of age. At 60 months of age, this number had increased to just over 20% (Figure 1).

Data on toothbrushing frequency were obtained from the 30-month time point to the 60-month time point. At 30 months of age, just over 75% of children were having their teeth brushed daily. This number stayed relatively stable over the duration of the study, with just over 80% of children having their teeth brushed daily by 60 months of age.

3.3 Fluid consumption practices

Survey items on fluid consumption practices were administered over various time points, with information regarding whether children went to bed with a bottle collected for all time points from 18 to 42 months, and information on bottle, sippy cup or regular cup use collected for all time points from 18 to 48 months.

The majority of children went to bed with a bottle at least occasionally (69.7%-78.6%) from 18 to 30 months of age. At 18 months, just over a third of children were using a bottle as their primary drinking method. Bottle usage decreased as the child grew older until 48 months when bottle usage ceased in all participants (Table 2).

| Participants at each time point n (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time point (months) | 18 | 24 | 30 | 36 | 42 | 48 | 54 | 60 |

| Put to sleep with a bottle at least occasionallya | 103 (78.6) | 85 (64.4) | 65 (51.2) | 44 (34.1) | 33 (26.4) | - | - | - |

| Mostly uses a bottle to drink | 50 (38.2) | 28 (21.2) | 17 (13.7) | 10 (7.8) | 3 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | - | - |

- a This variable was calculated as a proportion of the total number of respondents to the survey, rather than the number of respondents to the item, due to a high rate of non-response to this item.

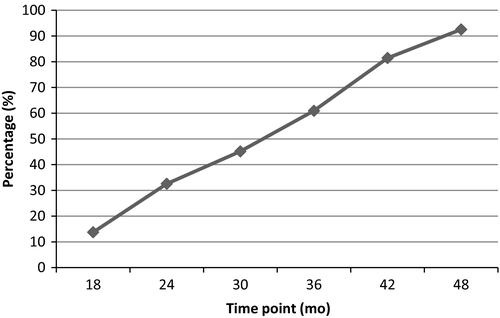

The data showed <20% of children were using a cup primarily to drink at 18 months of age. By 48 months of age, more than 90% of children were primarily using a cup to drink (Figure 2).

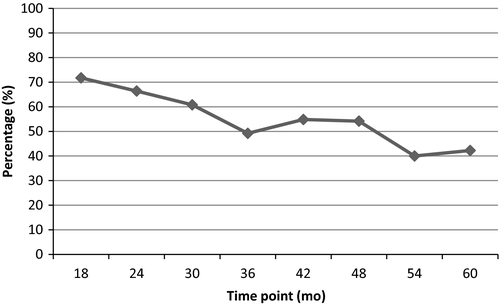

Information on drinks most often consumed was collected from the 18-month to the 60-month time points. For drinks other than milk, data suggested a high proportion of children consuming drinks with high sugar content (cordial, fruit juice and soft drink) as their most often consumed drink (Figure 3). This decreased over time, and less than half of children were consuming sugar-sweetened beverages as their primary drink by 60 months.

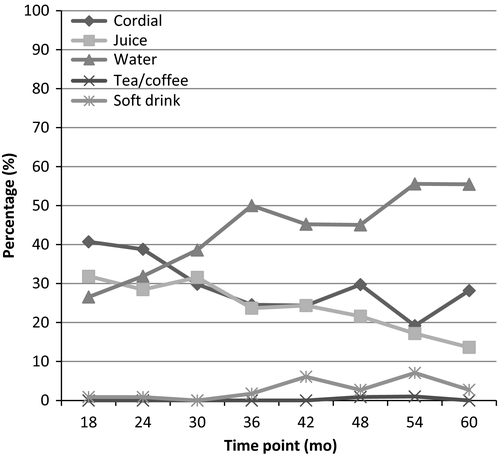

Cordial and juice were the most common drink consumed by children aged 18-24 months. From 36 months, the percentage of children with water as the main choice of drink increased, and by 60 months, the main drink consumed by 55.6% of children was water (Figure 4).

4 DISCUSSION

The Gudaga study describes the oral health behaviours and fluid consumption practices of young urban Aboriginal children of the Tharawal community in south-western Sydney. Although the study data presented are slightly dated (2007-2012), the findings provide a valuable contribution in this area as there is currently limited information on the oral health practices of urban Aboriginal children in Australia, particularly for the early childhood period.15 Most of the published literature on Aboriginal children under 5 years of age focuses on their uptake of dental services and hospitalisation rates for dental procedures during this period.19, 20

A low percentage of parents (10%-20%) in this study reported concerns regarding the oral health of the child during the age period of 2-5 years. It is difficult to assess whether this finding is an accurate representation of the oral health status of the child due to the lack of supporting clinical data. There is also no available population data on the prevalence rates of ECC among preschool Aboriginal children in NSW.21 The only comparable research has shown that nearly half the Aboriginal children under 6 years across rural and metropolitan NSW had dental caries.15 This suggests that there may be a disconnect among Aboriginal parents in this study regarding their perceived oral health concerns about the child and actual issues. However, this disconnect seems to be common among non-Aboriginal parents as well with population data showing parent-reported rates of caries for children (2-7 years) in NSW ranged from 3.1% to 26.5% despite the high prevalence rates (40%) of ECC reported.20 Some of the factors cited internationally that could contribute to parents under-reporting children's oral health problems include lack of oral health awareness, poorer general health perceptions, socio-economic status and behavioural beliefs.22, 23 Further research is needed to identify whether similar contributing factors exist among parents of Aboriginal children in Australia.

The findings also reveal that very few Aboriginal children had consulted dental services during the 2-5 years (5%-20%) despite their access to the local Aboriginal Medical Services. These figures are lower than the population data for all children in NSW where usage of dental services was 14% for 2- to 3-year-olds and 54% for 6- to 7-year-olds.21 Although dental service access during the early childhood period (2-3 years) has been consistently poor across all communities in Australia,19, 24 the low uptake among Aboriginal children is concerning as they have significantly higher rates (twice the levels) of dental caries compared to their non-Aboriginal counterparts.11, 15, 21, 25 What is more concerning is the extremely low attendance rates at 2 years (5%) especially as all children are recommended to receive a dental check up by this age.4 Without regular oral assessments early childhood caries can develop prior to 2 years and lead to a negative impact on the health and well-being of the child.26 Generally, Aboriginal children in urban areas have lower caries rates than those in rural settings 15 due to improved access to fluoridated water and affordable dental services.11 However, the study findings here suggest that there may be other barriers facing urban children regarding their oral health that need to be explored to promote early childhood oral health and improve dental service uptake.

The timely commencement of tooth brushing and its frequency can play an important role in lifelong oral health care. Parents are recommended to commence cleaning their child's teeth as soon as they erupt and to brush their child's teeth using a toothbrush and toothpaste at 18 months.4 Any delay beyond 30 months can increase the risk of the child developing dental decay.27 Further, brushing at least twice a day with fluoride toothpaste provides maximum exposure of fluoride to the tooth thereby reducing decay. In this study, at 30 months of age, more than 2-thirds of the children (75%) were brushing at least once a day and this remained stable till 60 months (76%-89%). These figures are very encouraging especially considering most of these children had not received a dental check, which is a known contributing factor to children commencing tooth brushing early.27 These figures are also higher than population data from Queensland, which show that only 35% of Aboriginal children had commenced brushing at 30 months. The findings suggest that urban Aboriginal parents are instilling preventative oral hygiene behaviours in their children. Due to the nature of the interviews, it was not possible to ascertain how many of these children were actually brushing twice a day and thus following current recommendations. The only comparative data from NSW show that the number of children brushing less than twice a day ranged from 58% for children 2-3 years to 41% for 6-7 years old.2 Future studies need to explore in more detail tooth brushing frequency habits of urban Aboriginal children to facilitate better comparisons with population data. Nevertheless, the fact that a large proportion of these Aboriginal children are brushing at least once a day is a positive sign as even 1 exposure to fluoride toothpaste will have a significant caries preventative effect.28

Fluid consumption practices can play an important role in the progression of early childhood caries.29 In this study, a high proportion of children (64.4%-78.6%) went to bed with a bottle at least occasionally during the 18-30 months age. This practice continued for a third of the children until 42 months. Unfortunately, there are no relevant studies with which to compare the night-time feeding practices of young Aboriginal children. Looking more broadly, a large study across both Australia and New Zealand found that between 6% and 15% of children 0-3 years were being bottle fed through the night.30 The higher rates reported in our study are concerning as night-time milk consumption is 1 of the main factors that can contribute to childhood decay, due to the pooling of sugar in the mouth.29, 31 Hence, it is strongly recommended that children should never go to bed with a bottle.4 Further research is warranted to confirm the prevalence of night-time fluid consumption practices among Aboriginal children especially as there is a paucity of research in this area and there was a high rate of non-response for this item in this study.

One strategy to reduce the risk of early childhood caries is to minimise prolonged use of bottle and introduce drinking from a cup by 12 months of age.4, 31, 32 Using a cup the sugar in drinks moves past the teeth very quickly and does not pool in the mouth. In this study, <20% of children were primarily using a cup to drink at 18 months of age. This usage did gradually increase to 90% at 48 months. However, the delay in commencing using a cup along with night-time bottle feeding puts these children at a greater risk of dental decay. The situation is further exacerbated by the drinking habits reported for these children. Apart from milk, a high proportion of children were found to be consuming sugar-sweetened beverages (cordial, fruit juice and soft drinks). This usage was most frequent during the first 2 years with cordial and juice being the most common drink (38%-40%). Although not explored in this study, it is possible that parents provided fruit juices to children as they perceived it to be a healthy way to provide vitamins and nutrition to the child.33 Nevertheless, these beverages have the potential to cause damage to teeth because of their high sugar content and acidic properties, especially when consumed frequently and during tooth eruption periods (8-33 months).34, 35 It is encouraging to note that the main drink of choice for a large majority of children from 36 months was water. Although we cannot be certain these children were drinking tap water, this is a highly recommended practice, especially in areas where water fluoridation exists, as it is an effective preventative strategy for dental decay.30

In summary, this study has provided some mixed findings regarding the oral health behaviours and fluid consumption practices of urban Aboriginal children. On 1 hand, it appears that many Aboriginal parents are promoting good oral hygiene habits among children by commencing their tooth brushing at an early stage and ensuring sufficient brushing frequency. Although these habits are not optimum as per current recommendations, they are a step in the right direction. Furthermore, parents are gradually weaning their children off bottles when they are older and encouraging water as an alternative drink of choice. On the other hand, it does appear that many parents are engaging in poor practices in the early years that can increase the risk of early childhood decay, such as night-time feeding with a bottle, providing drinks with high sugar content, and not seeking regular dental check-ups for the child. These findings suggest greater oral health awareness is needed among parents regarding risk factors for dental decay, as well as the importance of consulting dental professionals early even if there are no perceived dental issues. More work could also be done with the local Aboriginal community to develop programs to increase dental health literacy.

There are a number of limitations to this study. Firstly, this study relies on the parental report of their child's oral health, as there were no clinical data to validate their oral health status. Several studies though have used parental reports as indicators of children's oral health and found them to have satisfactory validity.22, 36, 37 It is also suggested that the accuracy of parental reports improves with increasing disease levels 37 and there is tendency for under reporting from parents when their children are young.22 As such, it is quite likely that our findings are an underestimation of the oral health status and practices of the child. Early childhood studies are thus needed among Aboriginal children that incorporate clinical oral health assessments. Currently, the study investigators are trying to address this gap by following up a similar cohort of Aboriginal children from south-western Sydney and clinically assessing their oral health.38 Obtaining validated measures like decayed, missing and filled index for teeth (dmft) and individual surfaces (dmfs) from these children would provide a true picture of their oral health status and allow better comparison with other population oral health data.15

Future studies in this area could also try and capture rates of dental hospitalisation and general anaesthesia among Aboriginal children as an additional proxy measure of oral disease. This is particularly relevant for young Aboriginal children (0-4 years) as they tend to have higher rates of hospitalisation for dental problems 20 and dental general anaesthetic care 39 than their counterparts of similar age. Another study limitation is the small sample size that makes it difficult to generalise the findings. Nevertheless, this study has provided a valuable insight into this under researched area of Aboriginal childhood oral health and has greatly informed the focus and methodology of future longitudinal studies on this topic.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the Tharawal people of south-west Sydney. Without the cooperation and enthusiasm of these traditional land owners, this research would not be possible. We thank the mothers who participated in this study for we could not undertake this research without their willingness to be involved. We would also like to acknowledge the Tharawal Aboriginal Corporation, South Western Sydney Local Health District, University of New South Wales and NSW Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council for ongoing support and the research team involved in data collection (Sheryl Scharkie) and project management (Jennifer Knight). Funding is also gratefully acknowledged from the National Health and Medical Research Council (300430, 510171).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in connection with this article.