Is this health campaign really social marketing? A checklist to help you decide

Abstract

Issue addressed

Social marketing (SM) campaigns can be a powerful disease prevention and health promotion strategy but health-related campaigns may simply focus on the “promotions” communication activities and exclude other key characteristics of the SM approach. This paper describes the application of a checklist for identifying which lifestyle-related chronic disease prevention campaigns reported as SM actually represent key SM principles and practice.

Methods

A checklist of SM criteria was developed, reviewed and refined by SM and mass media campaign experts. Papers identified in searches for “social marketing” and “mass media” for obesity, diet and physical activity campaigns in the health literature were classified using the checklist.

Results

Using the checklist, 66.6% of papers identified in the “SM” search and 39% of papers identified from the “mass media” search were classified as SM campaigns. Inter-rater agreement for classification using the abstract only was 92.1%.

Conclusions

Health-related campaigns that self-identify as “social marketing” or “mass media” may not include the key characteristics of a SM approach. Published literature can provide useful guidance for developing and evaluating health-related SM campaigns, but health promotion professionals need to be able to identify what actually comprises SM in practice.

So what?

SM could be a valuable strategy in comprehensive health promotion interventions, but it is often difficult for non-experts to identify published campaigns that represent a true SM approach. This paper describes the application of a checklist to assist policy makers and practitioners in appraising evidence from campaigns reflecting actual SM in practice. The checklist could also guide reporting on SM campaigns.

1 INTRODUCTION

Health campaigns have been used for many decades to inform communities and influence health behaviour, but more recently some have used a social marketing (SM) approach.1 SM is an evolving discipline with a strong consumer focus and a well-defined systematic approach to defining people's needs and achieving behaviour change.2, 3 SM aims to combine concepts and methods from marketing with those of other disciplines in order to “influence behaviours that benefit individuals and communities for the greater social good.”4 In combination with traditional health promotion participatory and empowerment strategies, a SM approach has considerable promise for improving the comprehensiveness and effectiveness of health campaigns, including those addressing chronic disease prevention.1

Nevertheless, not all self-proclaimed “SM” health interventions include the key components of a true SM approach including the “four Ps” of marketing (product, price, place, promotion).5 A common failing is to use only “communications and promotions,” without incorporating the other “Ps” and other SM processes such as target group segmentation, a clear voluntary exchange process, use of behaviour change theory, environmental change, and strategic formative research.2 Similarly, “mass media” health campaigns may focus only on the promotions element, but sometimes incorporate many of the key attributes of SM.6

Public health policy makers, researchers, and health promotion practitioners need to appreciate the components of a true SM approach—both for appraising evidence and for planning and implementing effective campaigns. In addition to guides on planning, implementation and evaluation of social marketing,7, 8 appraisal of the published literature is an important source of guidance for commissioning or designing campaigns; but identifying appropriate literature to review may be hampered as many campaigns are simply labelled as “SM” without further elaboration.9

This brief paper describes the development and application of a checklist designed to identify reports in the published literature of campaigns that apply a true SM approach to target obesity, diet and physical activity. The checklist provides succinct descriptions of criteria to help the user gather and use evidence from the literature on genuine SM in practice, as an aid in planning and conducting health campaigns that can support broader chronic disease prevention efforts.

2 METHODS

2.1 Development of checklist

Two members of the research team (author 1 and acknowledged contributor DH) developed an initial checklist of key and defining characteristics of SM campaigns based on published and grey literature and resources about definitions and characteristics of SM, as well as instructions on how to design and implement SM initiatives.2, 5, 7, 8, 10-14 This initial list was reviewed and further refined by the rest of the research team (all co-authors), who have expertise and extensive experience in SM and mass media campaign (MMC) design, implementation and evaluation.

2.2 Application of checklist to the literature

Two separate literature searches were performed focusing on SM and MMC to generate the sample on which to test the checklist. We restricted the search to obesity, diet and physical activity to facilitate comparisons with previous research.15 Searches in PubMed and Medline databases were limited to papers published in English between 1980 and October 2014. Our preliminary search included Scopus and CINAHL found sufficiently overlapping results that we decided the searches could be limited to PubMed and Medline. Both searches used the following terms—obes*, weigh*, overweigh*, BMI, “physical activity,” fitness, exercis*, nutri*, diet*, fruit, vegetable, “junk food” or sugary. These were combined with “social marketing” or “mass media” as a key word search.

Using the checklist, abstracts of extracted studies were classified by two researchers (author 2 and acknowledged contributor DH) independently to determine whether each study involved a campaign using an actual SM approach or another type of MMC without the necessary components of SM. Papers that satisfied all pre-determined SM campaign criteria were identified. Where multiple studies were based on the same campaign, they were considered independently.

3 RESULTS

3.1 The checklist

The final checklist of SM campaign-defining characteristics is presented in Table 1.

| Social marketing campaign characteristics | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Involves intervention(s) to change health-related behaviour; it may also address knowledge, attitudes and beliefs as antecedents to behaviour change. |

| 2. | Targets specific group(s) defined by formative research and segments audience based on particular characteristics (eg demographic, behavioural or psychographic variables). |

| 3. | Involves an exchangea; intervention provides adequate social value for the person and/or society to justify the efforts required for the person to adopt the promoted behaviour (the exchange of effort/price to acquire the value/benefits). |

| 4. | Employs mix of methods to develop and implement intervention; uses 4 Ps of marketing.

|

| 5. | Is guided by behaviour change theory.a |

- a These characteristics are often not apparent in the abstract and typically require review of the full article.

3.2 Application of the checklist results

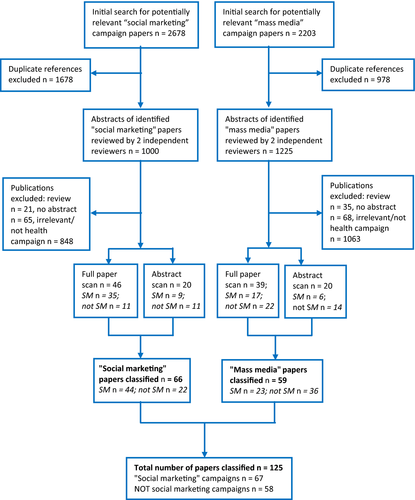

The initial database searches using “social marketing” as the key term, yielded 2678 potential papers (Figure 1). After removing duplicates, 1000 potential papers describing SM campaigns remained. Papers not using mass media communications, not containing a health message, plus review articles, or papers with no abstract were removed (n = 934). The checklist was applied to the remaining 66 papers, and 9 were classified as SM based on the abstract and another 35 based on the full text.

The “mass media” search initially yielded 2203 potential papers (1225 after removing duplicates). After removing papers as for the SM search above, and applying the checklist to the remaining 23 papers, 6 studies were classified as SM based on abstracts and a further 17 studies based on the full-text paper.

3.3 Classification of campaigns using the checklist

From 125 papers or abstracts reviewed, 67 (53.6%) were be classified as describing a SM campaign based on our criteria. Of these 67 studies, 52 (77.6%) required a review of the full paper to obtain sufficient information for classification. The remaining papers described health campaigns without all the required SM components including 22 papers which had “social marketing” in either the keywords, title or abstract. There was evidence of the same campaign being classified differently depending on which paper was being reviewed. For example, the using the checklist we classified ten of the 13 papers about the Verb™ campaign as SM, while the remaining three did not contain sufficient information to be deemed SM.

The initial inter-rater agreement rate for classifying papers as SM or mass media campaigns based on abstracts was 92.1%, while that for classifying the full-text paper was 77.3%. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and consultation with a third member of the research team (author 1).

4 DISCUSSION

As SM becomes a more commonly reported approach to chronic disease prevention and health promotion, it is important that decision makers understand the essential elements of SM and can then use the findings of SM campaigns to inform policy and intervention development. The checklist used in this study provides a practical tool and offers one approach for achieving this aim.

Using our checklist we found higher proportions of genuine SM efforts in the published literature compared to previous studies. Both McDermott and colleagues15 and Gordon and colleagues16 applied Andreasen's six benchmarks of SM5 to their search for SM interventions in the literature; McDermott et al found only 27 out of 200 papers on nutrition met these criteria (using only two of the SM Ps [promotion and at least one other]). Gordon et al applied the criteria to reports of diet, physical activity and substance use interventions and identified SM studies in: 31 of 67 articles on nutrition, 22 of 110 articles on physical activity, and 35 of 310 papers on substance misuse interventions. Many of these studies were small scale interventions, not mass-reach campaigns. Quinn and colleagues9 found 84 papers that contained “social marketing” in the title, abstract or methods; using Kotler and Zaltmans’ eight tenants of SM17 they found that 23 met at least two of the criteria while only three met all eight. They noted a “rather generous use of the term [social marketing] in the professional literature—often with little justification” (p. 339).

Considering our more restrictive SM definition that required all four Ps to be evident plus four other criteria, the higher number of genuine SM papers found in our study is somewhat surprising. Given differing topic areas and definitions between studies, comparisons are difficult. However, our higher rate could be due to the relatively long search timeframe or due to more published reports of SM campaigns in these selected topic areas18; it could also reflect increasing sophistication in campaign design and reporting by public health SM practitioners in recent years. The search timeframe encompassing 1980-2014 could be a limitation, despite the 34-year timeframe being longer than those employed in earlier studies,9, 16 as more recent literature describing campaigns using SM approaches would not have been captured. Our search also included the term “mass media,” and this may have increased the chances of finding interventions that could be classified as SM, since “mass media” campaigns often include other SM principles apart from the “promotion” communications component. McDermott et al15 also noted that some interventions not called SM did in fact meet their criteria.

It is possible the true number of examples of SM campaigns in the literature may have been higher because some articles could have been excluded simply due to not providing sufficient information (eg, Verb™). We found that some SM criteria are complex or imprecise and therefore harder to identify. For example, the concept of “exchange” was difficult to ascertain from the abstract and required a review of the full-text in many cases. McDermott et al also described the difficulty of assessing papers against some of the SM criteria.15 In general, journal space is tight and abstracts contain limited information, therefore our SM checklist may need to be applied to the whole paper.

Taken together, these findings indicate that to identify genuine health-related SM campaigns it is insufficient to rely on papers that self-identify as taking a SM approach, or those that are identified in “social marketing” database searches. Nor is it reasonable to assume that a “mass media” campaign is not SM. There is a need for clearer reporting of SM interventions, so genuine examples in the published literature can be more easily identified. The checklist described in this paper provides a succinct distillation of current SM evidence into relevant descriptions of key characteristics of SM. This checklist tool was designed to assist health promotion policy makers and practitioners, who may not be experts in SM approaches, in appraising evidence about SM in practice, and support planning and implementation of SM campaigns. It could also guide those reporting on SM campaigns to ensure that key details of the SM approach are described in their publications.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dominique Hespe for her contributions to this project. JYC was supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship (#100567) from the National Heart Foundation of Australia. This work was partly funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) through its Partnership Centre grant scheme (GNT9100001). NSW Health, ACT Health, the Australian Government Department of Health, the Hospitals Contribution Fund of Australia and the HCF Research Foundation have contributed funds to support this work as part of the NHMRC Partnership Centre grant scheme.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Tom Carroll is Director of Carroll Communications, a social marketing and research consultancy. All other co-authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in connection with this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

JYC, AB conceived this study. JYC designed the study methods. Dominique Hespe (DM), BM and JYC conducted the database searches and coded results. All authors contributed to checklist design and interpreted the results. JYC, BM, MMT, ACG and DM prepared the draft manuscript. All authors critically reviewed, revised and approved the manuscript.