Engaging hepatitis C infected patients in cost-effectiveness analyses: A literature review

Potential conflict of interest: Dr. Mattingly advises for Summit and received grants from ALK.

Abstract

Cost-effectiveness analyses (CEAs) of hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment strategies have become common, but few appear to include patient engagement or the patient perspective. The objectives of the current study were to (1) identify published HCV CEA studies that include patient input and (2) derive insights on patient-informed variable and outcome selection to build a framework for future economic analyses of HCV. A literature search was conducted using SCOPUS, EMBASE, and PubMed from January 1, 2012 to May 28, 2017. Terms sought included a combination of “incremental cost-effectiveness ratio” OR “economic evaluation” OR “cost effectiveness analysis” OR “cost utility analysis” OR “budget impact analysis” OR “cost benefit analysis” AND “hepatitis C”. A total of 1,040 articles were identified in the search and seven articles were selected for further evaluation after abstracts and the full text of eligible articles were screened. One economic evaluation used direct patient engagement to account for patient preferences in the final model. The study endpoints identified included a variety of clinical, social, psychological, and economic outcomes. Costs primarily focused on productivity loss, missed work, out-of-pocket treatment costs, and indirect costs to family or friends supporting the patient. Conclusion: To date, the inclusion of the patient voice through patient engagement as part of methods in cost-effectiveness research in existing published studies has been limited. Future CEA studies should consider how patient engagement may impact economic models and their implementation into practice. (Hepatology 2018;67:774-781).

Abbreviations

-

- CEA

-

- cost-effectiveness analysis

-

- CER

-

- comparative effectiveness research

-

- DAA

-

- direct-acting antiviral

-

- HCV

-

- hepatitis C virus

-

- PCOR

-

- patient-centered outcomes research

-

- PRISMA

-

- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

-

- QoL

-

- quality of life

-

- RCTs

-

- randomized controlled trials

Background

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) is estimated to affect more than 3 million Americans and is characterized by both hepatic and extrahepatic manifestations that can impact patients' lives.1, 2 In terms of direct economic burden, substantial costs are historically associated with advanced disease and inpatient care.3-5 Recent innovations in drug therapy provide the opportunity for clinical cure of this chronic infection. But, these therapies are also very costly and have created challenges for decision makers responsible for the care of larger populations.6, 7

Comparative effectiveness research (CER) encompasses investigations into the benefits and harms of multiple health care alternatives for clinical conditions to aid patients, providers, payers, and policy makers in making more informed decisions to improve delivery of care and outcomes.8 Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) is a type of economic evaluation that allows for comparison of different interventions on the basis of health outcomes and costs.9 The results of a CEA typically estimate an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio to help decision makers compare various treatments available.9 The inclusion of CEA within CER has been met with controversy because of concerns that the inclusion of cost data could result in rationing or reduced access.10, 11 Despite reluctance to formally incorporate CEA into CER decision analyses by some, the health insurance industry uses costs—in some form—to project the effect of a new technology on budgetary constraints.11 Varied CEA method selections by different researchers also remains a key implementation barrier. Lack of consensus can raise questions regarding the soundness of CEA approaches.11, 12 The issue of inconsistent methods is compounded by recent attention to the inclusion of patient preferences and shared decision making, opening any form of comparative evaluation research to further criticism if ignored.13

In the case of chronic HCV, many recent CEAs have been conducted by modeling the costs of the new pharmacological treatment and the savings associated with preventing downstream inpatient costs as the disease progresses.7, 14 To determine costs and effects for economic models, researchers typically rely on secondary data from clinical trials or observational studies, or opinions from experts in the field.15, 16 Model inputs gathered from literature review, meta-analyses, or expert opinion may help CEA researchers build a sound model for a payer or for society as a whole. But without patient engagement, how do we know if the final results are of importance to the end user or that the model endpoints included are even valid from the perspective of the patient?

This study aims to (1) identify published HCV CEA studies that include patient input and (2) derive insights on patient-informed variable and outcome selection to build a framework for future economic analyses of HCV.

Methods

A literature search was conducted using SCOPUS, EMBASE, and PubMed from January 1, 2012 to May 28, 2017. The search included a combination of “incremental cost-effectiveness ratio” OR “economic evaluation” OR “cost effectiveness analysis” OR “cost utility analysis” OR “budget impact analysis” OR “cost benefit analysis” AND “hepatitis C”. Two, nonauthor reviewers were assigned half of the abstracts for screening and two separate nonauthor reviewers were assigned the other half. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance and were included for full-text review if patients were engaged in determining the methods and/or conduct of the study. After completion of abstract review, the primary author assessed the rate of discrepancies between reviewers and required a full second screening if 20% or greater discrepancy. Discrepancies were resolved between the two reviewers through discussion with the primary author.

Articles were not included if they merely provided patients with a survey instrument to assess quality of life (QoL) or other patient-reported outcome. Whereas QoL may be an important outcome, simply collecting QoL does not reflect true engagement in determining which outcomes are most important to the patients involved. Qualitative data collection methods, to include interviews, semistructured interviews, or group panels, were sought for this review.

Data extraction from the included full-text articles was completed by the primary author. The following variables were extracted from each article for review: citation details; study methods; study objective; method(s) of patient engagement used; potential effects; and potential costs. Potential costs and effects derived from each article describe any positive or negative consequences of the disease or treatment.

Results

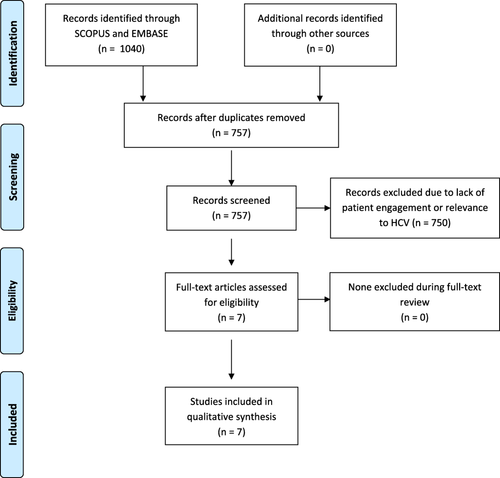

A total of 1,040 articles were found during the initial search with 283 duplicates, for a total of 757 articles for screening. An additional 750 articles were removed during abstract screening because of lack of patient engagement or relevance to HCV and reviewer agreement on inclusion of articles for full-text review was 92.3% (699 of 757). No articles were excluded during full-text review. A total of seven articles were included for data abstraction (Table 1).17-23 The full results of the search strategy are provided in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart (Fig. 1).24

| Authors | Year | Title | Type | Study Objective | Patient Engagement | Potential Effects Identified | Potential Costs Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groessl E.J. et al. | 2017 | Cost-Effectiveness of the Hepatitis C Self-Management Program | RCT and economic model | Evaluate the cost-effectiveness of an HCV self-management program | Weekly 2-hour workshops with interactive modules; interviews | HRQoL from QWB-SA tool, self-efficacy, energy/fatigue, depression, HCV knowledge score, distress, exercise | Focused on program cost: training, time for workshop sessions, phone call reminders, printed materials, refreshments, and overhead |

| Mühlbacher and Sadler | 2017 | The Probabilistic Efficiency Frontier: A Framework for Cost-Effectiveness Analysis in Germany Put into Practice for Hepatitis C Treatment Options | Economic model | To calculate an efficiency frontier by taking patient preferences and uncertainty into account | Semistructured interviews | Probability of sustained virological response, frequency of injections, therapy duration, gastrointestinal symptoms, anemia, skin reactions, tiredness/lethargy, headaches | Focused comparison on short-term costs of treatment regimens |

| Henry L., Younossi Z. | 2016 | Patient-reported and economic outcomes related to sofosbuvir and ledipasvir treatment for chronic hepatitis C | Review | To review patient-reported and economic outcomes related to DAAs | No direct engagement in review, but review focused on patient-reported outcomes | Impact of disease progression, impact of treatment, patient's ability to work, and patient's level of fatigue | Drug costs, health care cost offsets, adverse event costs, and increased worker productivity |

| Mhatre and Sansgiry | 2016 | Development of a conceptual model of HRQoL among hepatitis C patients: A systematic review of qualitative studies | Review | To develop a preliminary model of health-related quality of life among HCV patients | No direct engagement in review, but review focused on patient-reported outcomes | Physical symptoms, physical activities, guilt, stigma, emotional distress, psychological behavior, social relationships, social activities, work function, sexual function, cognitive function | Inability to work, opportunity costs for family members required to take on additional work, additional comorbidities |

| Roberts K. et al. | 2016 | Hepatitis C - Assessment to Treatment Trial (HepCATT) in primary care: Study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial | Cluster RCT with nested qualitative study and economic analysis | To evaluate a complex intervention in primary care to identify high-risk and untreated HCV patients | Semistructured interviews | Patient perception of effectiveness of being approached for an HCV test in primary care, acceptability of being approached, and experiences with referral and ongoing treatment | Costs of primary care staff training, cost of software, unit costs of provider interventions and consultations, incremental costs of new diagnoses |

| Matza L.S. et al. | 2015 | Health state utilities associated with attributes of treatments for hepatitis C | Time trade-off interviews | To estimate utility associated with treatment and adverse events | Semistructured interviews | Frequency of dosing, oral vs. injection, adverse events rankings (anemia, flu-like symptoms, rash, depression) | Cost of burdensome regimens, injections, fatty food requirement for some treatments, and cost of adverse effects during treatment |

| Quartuccio L. et al. | 2013 | Health-related quality of life in severe cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis and improvement after B-cell depleting therapy | Quality-of-life survey and proposed economic analysis | To examine HRQoL scores in patients with severe CV and analysis on impact of rituximab on HRQoL | Semistructured interviews | SF-36 domains (physical, role physical/emotional, bodily pain, general health, social function, mental health, vitality) | Costs of rituximab in addition to other treatment costs |

- Abbreviations: HRQoL, health-related quality of life; CV, cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis; QWB-SA, Quality of Well-Being Scale Self-Administered; SF-36, The Short Form-36.

Of the articles included for analysis, four studies involved a component of direct patient engagement using semistructured interviews whereas two studies included were systematic reviews of patient-reported outcomes. Two of the studies were working alongside randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and one study was purely focused on time trade-off interviews to estimate patient-reported utility associated with treatment and adverse events. In terms of study objectives, researchers were interested in developing models of QoL assessment specific to having HCV infection. In terms of a traditional economic evaluation, only one study used model input weighting from direct patient engagement methods.

Potential effect identified included a variety of clinical, social, psychological, and economic outcomes. Potential costs primarily focused on productivity loss, missed work, out-of-pocket treatment costs, and indirect costs to family or friends supporting the patient.

Discussion

Hepatitis C has garnered much attention in recent years as the approval of expensive direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimens have offered very effective cure rates compared to previous standards of care.6 When searching for economic models within the HCV literature, several CEA studies were identified; however, most economic analyses did not include any sort of patient engagement in the methods throughout the process of determining a “cost-effectiveness” result. Although, at first glance, this may seem surprising, it is important to consider the historical context of patient engagement. The demand for health economic information along with clinical outcomes has a longer history than the more recent efforts in patient-centered outcomes research (PCOR), which has gained traction with the passage of the Affordable Care Act and the formation of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.25, 26 In addition to the evolving interest in PCOR, the development of sound methods or approaches to patient engagement has also been a more recent advancement.27

The recommendations by the International Society of Pharmaceutical Outcomes Research task force on modeling suggest that any model structure should “reflect the chosen decision-making perspective.” Thus, traditionally, the design of the model and determination of inputs and outputs are dependent on whether the researchers are interested in a patient, payer, or societal perspective. When the anticipated end user of an economic model is a payer for pharmaceutical services (i.e., government or private managed care), it would make sense to focus on the costs and effects that matter to that audience. However, successful implementation of any health service also relies on the active participation of the ultimate end user of the service, which is undoubtedly the patient. Shifting modeling methods to include patient input may result in more informed decision making encompassing the factors that impact real patients dealing with the disease.

Patients infected with HCV face a variety of negative physical, social, and psychological effects associated with a disease that spans beyond the impact of the virus. Physically, patients may experience severe levels of fatigue that debilitates their productivity at home or work.17-19, 22, 23 This physical effect may influence them psychologically and socially as they struggle with routine chores or even lose their jobs altogether.23 Socially, HCV has stereotype associations that may cause family, coworkers, employers, or friends to avoid the patient.23 The reverse may also be true given that the patient may avoid social interactions for fear of embarrassment. This additional social anxiety may cause additional psychological stress for the patient or financial impact if the patient loses his or her job. Curing the disease with a pharmaceutical agent may help improve damaged relationships caused by the infection and any financial implications.

Work productivity loss or job loss was frequently cited as a negative effect and also a cost to the patient.19, 23 The fatigue associated with the disease may attribute to inability to focus at work or the lack of energy to physically complete a task.19, 23 Once a patient is cured of the disease, one could assume that relieving fatigue would allow the patient to return to a predisease normal level of activity. However, it may be difficult to achieve a total recovery to a pre-HCV state given that many of these patients may have suffered from the disease for many years before a treatment that offers cure was approved. Incorporating patient-engagement methods could inform the degree to which patients return to a predisease state or whether psychological and sociological relicts remain from years of living with the disease.

Economic analyses commonly use decision analytic models or regression analyses to inform decisions that are frequently plagued by uncertainty within the selection of model parameters, model structure, and methodological approach chosen by the research team.28 These sources of uncertainty require complex sensitivity analytics and yet differences in methods by researchers may still yield inconsistency in the model results adding further challenges in interpretation.28-30 Engaging patients throughout the process of conducting CEA of HCV therapies could help inform the most common sources of uncertainty in these types of models. Mullins et al. recommends a continuous engagement approach to not only identify the topics important to patients, but also to help verify the conceptual framework and assist in translating and disseminating the results of the model.27

In recent years, several organizations have attempted to develop value frameworks to assess drug prices based on the improvement of patient outcomes.31 A 2016 report produced by Avalere Health found that the inclusion of the patient perspective was limited in the four major value frameworks published.32 The role of patient input in economic models that assess the value of a treatment has yet to be determined, but failing to consider patient preferences may result in misappropriating resources for outcomes that are not meaningful to those being treated.

This review had a number of limitations. First, only published studies were included in order to capture relevant research information in the methods and results of the study. It is possible that some studies may have engaged patients directly, but failed to include any language in the title or abstract to reflect this engagement, which would have led to exclusion from this review.

Conclusion

The use of patient-engagement methods in cost-effectiveness research has been limited. Future CEA models should consider how patient engagement throughout a comparative study may impact model results in a way that improves patient buy-in and implementation into practice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anne Fulton, Meryam Gharbi, Divya Shridharmuthy, Anne Williams, and Melissa Yuen for their assistance with review and screening of article abstracts.