Drug rechallenge following drug-induced liver injury

Potential conflict of interest: Christine M. Hunt has received consultancy fees from Otsuka and Furiex. Julie I. Papay was employed at UCB Biosciences during the preparation of the manuscript. Vid Stanulovic is employed at Accelsiors Clinical Research Organization and Consultancy, Budapest, Hungary. Arie Regev is employed at Eli Lilly and Company.

Data from this study were shared previously at the FDA Critical Path Institute Drug-Induced Liver Injury Conference XVI, Hyattsville, MD, March 23, 2016.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the policies or position of, nor imply endorsement from, the US Food and Drug Administration, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the US Government.

Abstract

Drug-induced hepatocellular injury is identified internationally by alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels equal to or exceeding 5× the upper limit of normal (ULN) appearing within 3 months of drug initiation, after alternative causes are excluded. Upon withdrawing the suspect drug, ALT generally decrease by 50% or more. With drug readministration, a positive rechallenge has recently been defined by an ALT level of 3-5× ULN or greater. Nearly 50 drugs are associated with positive rechallenge after drug-induced liver injury (DILI): antimicrobials; and central nervous system, cardiovascular and oncology therapeutics. Drugs associated with high rates of positive rechallenge exhibit multiple risk factors: daily dose >50 mg, an increased incidence of ALT elevations in clinical trials, immunoallergic clinical injury, and mitochondrial impairment in vitro. These drug factors interact with personal genetic, immune, and metabolic factors to influence positive rechallenge rates and outcomes. Drug rechallenge following drug-induced liver injury is associated with up to 13% mortality in prospective series of all prescribed drugs. In recent oncology trials, standardized systems have enabled safer drug rechallenge with weekly liver chemistry monitoring during the high-risk period and exclusion of patients with hypersensitivity. However, high positive rechallenge rates with other innovative therapeutics suggest that caution should be taken with rechallenge of high-risk drugs. Conclusion: For critical medicines, drug rechallenge may be appropriate when 1) no safer alternatives are available, 2) the objective benefit exceeds the risk, and 3) patients are fully informed and consent, can adhere to follow-up, and alert providers to hepatitis symptoms. To better understand rechallenge outcomes and identify key risk factors for positive rechallenge, additional data are needed from controlled clinical trials, prospective registries, and large health care databases. (Hepatology 2017;66:646–654).

Abbreviations

-

- ADPKD

-

- autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

-

- ALT

-

- alanine aminotransferase

-

- BSEP

-

- bile salt export pump

-

- DILI

-

- drug-induced liver injury

-

- FDA

-

- US Food and Drug Administration

-

- HLA

-

- human leukocyte antigen

-

- ULN

-

- upper limit of normal

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) remains a key cause of death from acute liver failure.1, 2 In a prospective US registry, 3% of patients with DILI progressed to liver-related death, 4% progressed to liver transplantation, and 17% developed chronic liver injury.3 Up to 5% of patients with DILI also suffer Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, with a 36% mortality rate (attributed to antiepileptic, antimicrobial, and antiretroviral drugs).4

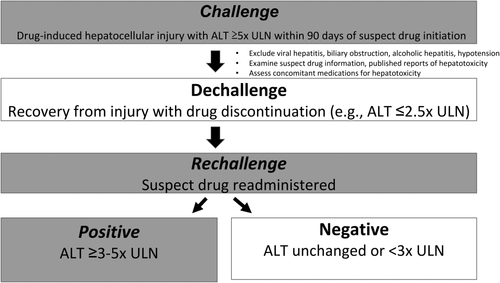

DILI is a common cause of hepatic injury identified by liver chemistry elevations, temporally related to the initiation and cessation of the suspect drug.5-8 Serious DILI is most commonly hepatocellular and is the focus of this review. Hepatocellular DILI is characterized by predominant alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevations of 5× the upper limit of normal (ULN),5, 7 appearing within 90 days of suspect drug initiation, which decrease by half or more within 1 month of drug cessation.5, 6, 8 DILI is further affirmed by excluding other causes (e.g., viral hepatitis, biliary obstruction, alcoholic hepatitis, or hypotension), reports of suspect drug hepatotoxicity, and liver injury recurrence upon rechallenge (or readministration) of the suspect drug—which has traditionally been strongly discouraged (Fig. 1).5, 6, 9 DILI may be misidentified in clinical practice, with nearly half of DILI reports not representing DILI on expert review.10 Designed for clinicians, internationally agreed scoring systems identify the likelihood of DILI as highly probable, probable, possible, unlikely, or excluded by tallying DILI findings.5, 6, 8

After DILI, most patients fully recover when the suspect medication is stopped. When liver chemistries normalize with drug cessation, this “positive dechallenge” suggests liver injury resolution and may implicate the suspect drug in the initial liver injury (Fig. 1).5 After a positive dechallenge, patients receiving benefit from a critical or life-saving medicine may be considered for drug rechallenge. Increasingly, drug rechallenge has been incorporated into controlled clinical trials of critical therapeutics. Recent prospective clinical studies examining hundreds of rechallenge events currently define a positive drug rechallenge as an ALT level of 3-5× ULN or greater, which generally occurs much more rapidly than the initial DILI.11-13 This new definition of positive rechallenge has largely replaced an earlier definition of ALT doubling for hepatocellular injury, empirically defined in 77 cases, which has not been substantiated further.9

High Risks in Drug Rechallenge

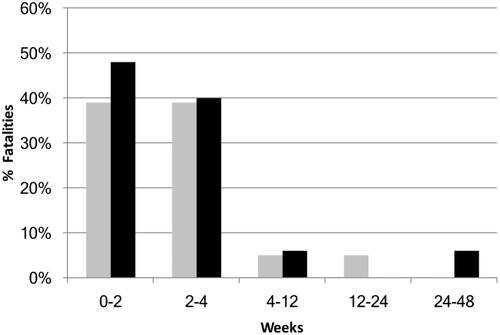

Compared with initial DILI, drug rechallenge is associated with even greater risks. For example, among those rechallenged with halothane within one month of halothane re-exposure, nearly half died (Fig. 2).14 This resulted in the markedly decreased use of halothane and a heightened awareness of drug rechallenge–related liver injury. DILI and drug rechallenge of all prescribed drugs have been prospectively recorded and analyzed in the Spanish DILI registry for more than 20 years. In this series, 13% of patients exhibiting a positive drug rechallenge after predominantly hepatocellular DILI either died or underwent liver transplantation.15 These positive rechallenge events were also associated with frequent hospitalization (52%), jaundice (64%), and hypersensitivity (39%).15 Similarly, in a retrospective study of 88 positive drug rechallenge events, the highest-risk events occurred in patients with severe hepatocellular injury with jaundice, two of whom (2%) died.16 Furthermore, most positive rechallenge events occur more rapidly than the initial DILI: 1) in less than half the time in the prospective study,15 and 2) within 1 week of rechallenge in nearly half of those reported retrospectively.16 There are very limited published data on negative rechallenge,17 suggesting a bias to reporting positive rechallenge. Most drug rechallenge events are inadvertent (e.g., patients self-medicating months or years after DILI).16 Hence, by accurately identifying DILI and conveying to the patient their need to avoid suspect drug readministration, inadvertent drug rechallenge may be preventable.

A Small Minority of Drugs Account for Most Positive Rechallenge Events

Among the hundreds of drugs associated with hepatotoxicity, 48 drugs have more than 50 published cases each of DILI.18 These drugs include antimicrobials, central nervous system (e.g., antiseizure) drugs, and cardiovascular and oncology therapeutic drugs.18 In this high-risk subgroup, more than 90% are associated with at least one fatal liver injury and one positive rechallenge.18 In phase 2 and 3 studies, drugs associated with DILI exhibit a higher incidence of ALT ≥3× ULN in treated versus placebo groups, particularly when the daily dose exceeds 50 mg.19 In contrast, drugs with fewer DILI reports are associated with progressively lower fatality and positive rechallenge rates.18 When a similarly low incidence of ALT elevations in treated versus placebo groups is observed during clinical trials, liver safety is likely.19 This suggests that drug characteristics influence the risk of DILI, fatality, and positive rechallenge, including reactive metabolites, bile salt export pump (BSEP) inhibition, and mitochondrial impairment.15, 20, 21 Timely information on a drug's association with mitochondrial impairment can be obtained through an online search (i.e., drug name and mitochondrial impairment). Among drugs withdrawn from the market or labeled with a black box warning, 38% result in mitochondrial impairment, and most inhibit BSEP.21 An earlier systematic review of drugs with at least 10 well-documented rechallenge events revealed that the highest rate of positive rechallenge (and fatality) is observed in drugs associated with 1) immunoallergic injury and mitochondrial impairment (with positive rechallenge rates of up to 11%-51%), 2) hepatocellular injury, and 3) high daily drug dose (>50 mg).7, 20, 22 A list of 46 drugs with 10 or more events of DILI and at least one positive rechallenge is provided in Supporting Table S1. Among these drugs, 40 (87%) have a daily dose range >50 mg (observed in 40% of the most commonly prescribed US drugs)22 and half exhibit mitochondrial impairment in vitro.

In summary, in diverse medications, a drug's mechanism of liver injury, high daily dose, and clinical profile of injury inform rechallenge risk.

Personal and Environmental Risk Factors Affect Liver Injury

In addition to drug-specific factors, susceptibility to DILI varies by patient. For example, children with mitochondrial polymorphisms/disorders are highly susceptible to drug-induced acute liver failure and fatality.23-25 Furthermore, drug metabolism and immune response are influenced by concomitant medications, inflammation, and genetics.26, 27 More than a dozen human leukocyte antigen (HLA) markers are associated with an increased risk of DILI, which varies from less than 2-fold for isoniazid to a more than an 80-fold increase with flucloxacillin.28 However, in contrast to the 100% positive predictive value of HLA-B*5701 carriage for abacavir hypersensitivity,29 positive predictive values are generally low for DILI HLA markers, suggesting the importance of other factors.28

Drugs With Fatal or Frequent Positive Rechallenge

Through salient examples, we can examine drugs associated with fatal or frequent positive rechallenge. Halothane is associated with DILI with jaundice resulting in nearly 50% mortality with rechallenge. Halothane is oxidized to a trifluoroacetyl halide, which forms protein adducts.30 Immunoallergic injury occurs rapidly with halothane rechallenge, with fever, rash, eosinophilia, halothane adduct and auto-antibodies, and an associated HLA A-11 marker.31 Furthermore, by inhibiting mitochondrial complex I and II32 and fatty acid and pyruvate oxidation,33 halothane impairs mitochondrial function, resulting in critical cellular energy loss (as mitochondria provide 90% percent of cellular ATP).34 Mitochondria can regenerate, yet require 1 to several weeks for regeneration,34 leaving the hepatocyte vulnerable to a second “hit.” Patients rechallenged with halothane within the first month after halothane liver injury exhibit the highest fatality rate (Fig. 2), with nearly half of patients receiving halothane rechallenge resulting in death.14 This 1-month period aligns with the time required for mitochondrial regeneration, suggesting mitochondrial impairment contributes to immunoallergic injury in halothane positive rechallenge.

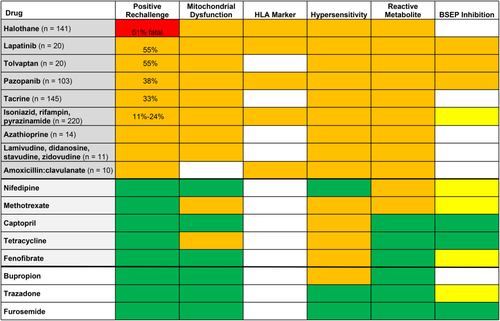

A more contemporary oral drug associated with frequent positive rechallenge (Fig. 3), lapatinib is a dual tyrosine kinase inhibitor effective in breast cancer. Lapatinib is metabolized in the liver to an electrophilic quinone imine which generates oxidative stress, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction, and also forms protein adducts, contributing to immunoallergic injury.35 Patients carrying HLA-DQA1*02:01 and HLA-DRB1*07:01 are particularly susceptible to lapatinib-induced liver injury (odds ratio, 14.0)36 and account for the majority of affected patients. Lapatinib metabolites also inhibit BSEP, blocking bile acid efflux from the hepatocyte and causing cytotoxicity. While primarily metabolized in the liver, lapatinib exhibits high intersubject variability in its metabolism and fecal elimination, and interacts with multiple drugs,37 likely further affecting liver injury. The microbiome also affects drug metabolism,38 and lipopolysaccharide can affect immune tolerance,39 further modulating liver injury. Thus, drug, host, and environmental factors interact to determine an individual's response to drug rechallenge, which ranges from asymptomatic adaptation without apparent liver injury to rapid, severe, and even fatal liver injury.

Drug Characteristics Influence DILI and Positive Rechallenge

Specific features identify drugs associated with high rates of DILI and positive rechallenge: daily dose exceeding 50 mg,7, 19, 22 predominant hepatic metabolism,7 hepatocellular injury, and evidence of immunoallergic injury40 or mitochondrial impairment in vitro.41, 42 Hepatotoxicity is evident in most drugs with preclinical testing exhibiting: reactive metabolites, marked metabolism-dependent cytochrome p-450 inhibition (with >5-fold change in IC50), covalent protein binding (≥200 pmol eq/mg protein), reactive oxygen species, glutathione adduct formation, lipophilicity (logP≥3), BSEP inhibition, cellular ATP depletion, mitochondrial toxicity, or cytotoxicity.21, 43-45 Modeling these preclinical tests in human hepatocyte culture, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) National Center for Toxicologic Research has identified two factors most predictive of serious clinical hepatotoxicity: 1) increases in oxidative stress and 2) decreases in cellular ATP (i.e., mitochondrial dysfunction).44 Mirroring these findings, immunoallergic injury from reactive metabolites and mitochondrial dysfunction were associated with the highest rates of clinically important positive rechallenge injury.20 After searching PubMed, Google Scholar, and FDA.gov and cross-referencing (2010-2016), recent data from drugs with 10 or more rechallenge events were incorporated with that of an earlier systematic review to highlight key drug characteristics in a heat map format (Fig. 3). When compared with drugs with few or no positive rechallenge reports, drugs associated with positive rechallenge exhibited both immunoallergic (i.e., hypersensitivity, reactive metabolite, and HLA marker) and mitochondrial injury.

Emphasizing the risks of drug rechallenge, the FDA DILI clinical trial guidance advises caution.46 Yet innovative therapeutics efficacious in inhibiting targeted cancer pathways continue to exhibit hepatotoxicity.47 Hence, in patients with DILI exhibiting efficacy, prospective oncology trials are increasingly examining drug rechallenge, using selective criteria (Table 1).11 With the rigorous monitoring of prospective clinical trials, we can better evaluate the efficacy and safety outcomes of drug rechallenge of critical medications.48

| 1. Evaluate the role of suspect drug in initial drug-induced liver injury |

| • Confirm DILI6 and exclude alternative diagnoses5, 7 |

| 2. Examine alternatives |

| • Is treatment continuation necessary? |

| • Are there safer therapeutic alternatives? |

| 3. Review suspect drug information for increased risk of positive rechallenge |

| • Higher incidence of ALT elevations in suspect drug vs control groups in clinical trials |

| • Reports of hypersensitivity (e.g., fever, rash, eosinophilia), HLA marker associated with liver injury |

| • Mitochondrial regeneration following injury requires 1 to several weeks |

| • Reports of suspect DILI with jaundice (i.e., serious liver injury) |

| • Severe or fatal liver injury or rechallenge reports in product label or publications |

| 4. Evaluate drug's clinical benefit and risks in patient being considered for rechallenge |

| • Is the patient receiving a compelling benefit that exceeds the risk of rechallenge? |

| • Has the patient exhibited hypersensitivity or drug-specific HLA markers, putting them at high risk of positive drug rechallenge (i.e., rechallenge to be avoided)? |

| • Has the patient experienced jaundice, coagulopathy, or encephalopathy (i.e., signs of liver failure) with the initial suspect DILI (i.e., rechallenge to be avoided)? |

| • Should a reduced dose be administered (or is this inappropriate, due to subtherapeutic exposure or possible resistance limiting clinical benefit)? |

| 5. Is rechallenge appropriate in this patient? |

| • Have the benefits and risks of drug rechallenge been discussed fully with the patient in shared decision making to assure a clear understanding and informed consent? |

| • Can the patient promptly report hepatitis symptoms and adhere to the required clinical follow-up? |

| • Has rechallenge been discussed with the Institutional Review Board or Ethics Committee? |

| 6. Report results of rechallenge |

| • Record results in the medical record and report to the FDA or health authorities |

Drug Rechallenge in Controlled Clinical Trials

With early evidence of efficacy and liver injury, pazopanib-controlled trials adapted protocols to enable drug rechallenge with attentive follow-up. Pazopanib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor effective in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma and soft tissue sarcoma. During clinical trials, ALT levels >8× ULN affected 5% of patients receiving pazopanib.11 In over 2000 patients in phase 2 and 3 studies, 103 patients developing pazopanib-induced liver injury were rechallenged if they derived clinical benefit from pazopanib, exhibited a positive dechallenge (with ALT levels decreasing to ≤2.5× ULN), and had no evidence of hypersensitivity.11 Patients were monitored with weekly liver chemistries for 2 months,49 and most received an initially reduced dose of pazopanib.49 Among the 103 patients, 62 (60%) displayed a negative rechallenge (or adaptation), 2 (2%) had incomplete follow-up, and 39 (38%) exhibited a positive rechallenge with ALT >3× ULN. In the 39 patients with a positive rechallenge, 31/39 (79%) exhibited an ALT ≤8× ULN and 8/39 (21%) developed an ALT >8-20× ULN at a median of 9 days. No patients developed severe liver injury with positive rechallenge. Risk factors for pazopanib-induced liver injury included older age,11 concomitant simvastatin treatment,49 and carriage of HLA-B*57:01, present in only 10% of patients with ALT >5× ULN.50 These data support the safety of pazopanib rechallenge with close monitoring.49 With pazopanib rechallenge after an event of likely pazopanib-induced liver injury, most patients exhibit adaptation to liver injury, rather than recurrence.

Critical to public health globally, tuberculosis medications are associated with high rates of DILI. Two prospective controlled clinical trials evaluated the safety of rechallenging patients with active tuberculosis following positive dechallenge, many of whom had severe symptomatic hepatitis or jaundice on initial isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide treatment.12, 13 In 220 patients rechallenged with isoniazid or rifampin, with or without pyrazinamide or ethambutol, most patients exhibited a negative rechallenge or clinical adaptation12, 13; 0%-24% of patients experienced nonfatal positive rechallenge (with negative rechallenge observed when pyrazinamide was excluded). The initial DILI severity did not increase the risk of positive rechallenge. No difference in rechallenge rates was observed when all drugs were restarted simultaneously or sequentially.12 Mechanisms contributing to positive rechallenge with tuberculosis medications include: isoniazid's reactive metabolite, an HLA DQB1*0201 marker associated with liver injury (odds ratio, 1.9),51 hypersensitivity, and mitochondrial impairment.52 Patients experiencing liver injury exhibited increased Th17 cells, anti-isoniazid and anti-cytochrome p-450 antibodies, hypoalbuminemia, older age, female sex, and alcohol use.51, 53

In contrast to the predominantly negative rechallenge observed with tuberculosis medications or pazopanib, 55% of patients exhibited a positive rechallenge with lapatinib or tolvaptan in small retrospective clinical trial reviews (Fig. 3).54, 55 These two compounds are associated with immunoallergic injury (with HLA marker carriage substantively increasing risk of lapatinib liver injury), mitochondrial impairment,35, 56 and BSEP inhibition.37, 57 Tolvaptan is a vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist indicated for hyponatremia and evaluated for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD).55 In ADPKD clinical trials, ALT >3× ULN was reported in 4% of tolvaptan-treated patients and 1% of patients receiving placebo, with three serious events of tolvaptan-induced liver injury (which resolved with treatment cessation).55 DILI developed after 3-18 months of tolvaptan administration, progressed for 1 month after treatment cessation, and resolved in a median of 1.5 months.55 In total, 20 patients were rechallenged with tolvaptan. Nine rechallenged patients exhibited adaptation, with ALT <3× ULN. Eleven (55%) patients exhibited rapid positive rechallenge (e.g., ALT 10× ULN) prompting tolvaptan cessation, with ALT normalizing in 1-4 months.55 With immunoallergic injury appearing likely, studies are reportedly underway to search for a possible HLA marker of tolvaptan-induced liver injury.55

Drug Rechallenge of Critical Medications

In prospective national registry studies of all drugs, drug rechallenge was associated with 13% mortality (or liver transplantation), and substantive comorbidity.15 Hence, drug rechallenge should generally be avoided. With innovative drugs targeting cancer or other critical pathways associated with DILI in development, prospective controlled phase 2/3 clinical trial data on drug rechallenge can inform the safety of targeted therapeutics48 and may enable safe rechallenge in clinical practice.58 In earlier described oncology clinical trials, drug rechallenge was safely performed in patients deriving a clinical benefit, without evidence of hypersensitivity, in whom ALT decreased to <2.5× ULN before rechallenge with a reduced dose of the suspect drug, and who completed 2 months of weekly liver chemistry monitoring.11 Additional prospective rechallenge data of diverse drugs is needed to better inform outcomes. These data can be obtained in large health care databases, from clinicians reporting rechallenge results to FDA MedWatch,59 and in prospective national DILI registries.

In a patient with a likely initial DILI event,5, 6 a critical medicine providing valuable patient benefits may be considered for drug rechallenge after DILI if 1) continued treatment is necessary and there are no safer therapeutic alternatives; 2) the patient is receiving a compelling benefit that exceeds the risk of rechallenge; 3) in shared decision making, the benefits and risks of drug rechallenge are discussed fully with the patient to assure a clear understanding and informed consent; 4) the patient agrees to immediately alert their provider if hepatitis symptoms arise (e.g., fatigue, nausea, abdominal pain, anorexia, or jaundice) and adhere to close clinical follow-up (e.g., liver chemistries at 1 week or less); and 5) an Institutional Review Board Chair discussion may be helpful (Table 1). Rechallenge results are then recorded in the medical record and communicated to the FDA or other health authorities.59 Although drug desensitization may be used before rechallenge,60 this approach may be infeasible for a critical medication requiring a specified therapeutic exposure threshold or when resistance may develop with subtherapeutic dosing. Dose reductions have been successfully used in prospective rechallenge studies,11, 13 yet data are limited. For patients exhibiting a positive rechallenge and liver failure with mild hepatic encephalopathy, N-acetylcysteine administration has proven beneficial in a controlled clinical trial.27 No other agents have proven efficacious in DILI.

Conclusions

Our broad review reveals that a minority of drugs that are administered at daily doses >50 mg and are associated with an increased ALT incidence in clinical trials, immunoallergic injury, and mitochondrial impairment in vitro are responsible for the highest rates of DILI and positive rechallenge. A patient's immune response, genetics, comedications, and other factors also influence positive rechallenge. With up to 13% mortality of drug rechallenge following DILI in prospective series of all prescribed drugs, drug rechallenge should generally be avoided. Large controlled studies have demonstrated that drug rechallenge of critical medicines can be performed safely, using standardized safety algorithms and weekly liver chemistry monitoring during the high-risk period.11 However, high positive rechallenge rates and clinically significant liver injury in other recent trials54, 55 suggest the need for controlled, cautious rechallenge of high-risk drugs. Drug rechallenge can be appropriate for critical medicines, when no safer alternatives are available and the patient's objective benefit exceeds their risk. Patients must be involved in shared decision making, alert providers to hepatitis symptoms, and adhere to close follow-up. Due to the high potential risk of drug rechallenge, Institutional Review Board discussion may be appropriate. When DILI affects a critical medication, controlled clinical trial assessment of drug rechallenge may afford adequate safety data to inform clinical practice. Further data from clinical trials, prospective DILI registries, and large health care datasets can inform rechallenge outcomes and identify key risk factors for positive rechallenge.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the informed, insightful discussions of participants at the FDA: Critical Path Institute Drug-Induced Liver Injury Conference XVI on March 23-24, 2016.